Abstract

The glycan chain of the S-layer glycoprotein of Geobacillus stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a is composed of repeating units [→2)-α-l-Rhap-(1→3)-β-l-Rhap-(1→2)-α-l-Rhap-(1→], with a 2-O-methyl modification of the terminal trisaccharide at the nonreducing end of the glycan chain, a core saccharide composed of two or three α-l-rhamnose residues, and a β-d-galactose residue as a linker to the S-layer protein. In this study, we report the biochemical characterization of WsaP of the S-layer glycosylation gene cluster as a UDP-Gal:phosphoryl-polyprenol Gal-1-phosphate transferase that primes the S-layer glycoprotein glycan biosynthesis of Geobacillus stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a. Our results demonstrate that the enzyme transfers in vitro a galactose-1-phosphate from UDP-galactose to endogenous phosphoryl-polyprenol and that the C-terminal half of WsaP carries the galactosyltransferase function, as already observed for the UDP-Gal:phosphoryl-polyprenol Gal-1-phosphate transferase WbaP from Salmonella enterica. To confirm the function of the enzyme, we show that WsaP is capable of reconstituting polysaccharide biosynthesis in WbaP-deficient strains of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium.

Glycoconjugates play an important role in many recognition, signaling, and adhesion processes in all living organisms (32, 50). Once thought to be restricted to eukaryotes, the existence of prokaryotic glycoproteins is now unequivocally established (9, 16, 22, 45, 48). Manipulation of cell surface glycosylation patterns by carbohydrate engineering techniques requires specific glycosyltransferases, glycosidases, nucleotide-sugar synthases, and transporters (12, 37). Therefore, an understanding of the bacterial glycosylation machinery is a prerequisite for successful application of glycoengineering in prokaryotes (10, 51).

Prokaryotic surface (S) layer glycoproteins represent a natural self-assembly system enabling high-density surface display of glycans in a nanometer-scaled, periodic way (for a review, see references 42). Glycosylated S-layer proteins contain highly variable glycans (41) which show significant similarities to the overall structure and constituent glycoses of O and K antigens of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and capsular polysaccharides (CPS) (38). LPS and CPS are characteristic components of the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria (29, 55). Moreover, the recently sequenced S-layer glycosylation (slg) gene clusters of Geobacillus stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a (GenBank accession number AF328862) and Aneurinibacillus thermoaerophilus strains L420-91T (GenBank accession number AY442352) and DSM 10155/G+ (AF324836) show high sequence homology to gene clusters involved in O antigen biosynthesis (24, 25, 36). The slg gene clusters contain components for glycan precursor biosynthesis and S-layer glycan assembly and export. These findings, together with the characterization of nucleotide diphosphate-activated sugar precursors (13, 17, 28) and lipid-activated intermediates (14), indicate that S-layer glycan and O-polysaccharide biosyntheses share common pathways.

The S-layer glycoprotein glycan of G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a, which serves as a model system in this study, possesses a tripartite architecture (39). The core unit consists of two or three l-rhamnose residues [→2)-α-l-Rhap-(1→3)-α-l-Rhap-(1→3)-α-l-Rhap-(1→], which are O-glycosidically linked via a β-d-galactose residue to threonine590, threonine620, and serine794 of the mature S-layer protein SgsE (39, 43). The glycan chain has, on average, 15 identical l-rhamnose trisaccharide repeating units with the structure →[2)-α-l-Rhap-(1→3)-β-l-Rhap-(1→2)-α-l-Rhap-(1→. The terminal trisaccharide repeating unit at the nonreducing end is capped with a 2-O-methyl group (39). A complete characterization of the enzymes encoded by the slg gene cluster is necessary to fully understand S-layer glycoprotein glycan biosynthesis.

The deduced 471-amino-acid sequence of WsaP (formerly called ORFG113 [25]; the protein was renamed WsaP according to the Bacterial Polysaccharide Database [31; http://www.microbio.usyd.edu.au/BPGD/default.htm]) of the slg gene cluster of G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a shows high homology to glycosyltransferases that catalyze the first step in capsule and exopolysaccharide biosynthesis by transferring hexose-1-phosphate residues from UDP-hexoses (galactose and glucose) to a phosphorylated lipid carrier. Prototypes for such initiation enzymes include WbaP from Escherichia coli (8), WbaP (formerly RfbP) from Salmonella enterica (52), and EpsE (44) and CpsE (1) from Streptococcus thermophilus. Here we report that the initiation enzyme WsaP of the S-layer glycoprotein glycan biosynthesis of Geobacillus stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a is a UDP-Gal:phosphoryl-polyprenol Gal-1-phosphate transferase. Our results show that (i) WsaP displays in vitro galactosyltransferase activity, (ii) WsaP can reconstitute polysaccharide biosynthesis in galactosyltransferase deletion strains of E. coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, and (iii) the C-terminal half of WsaP carries the galactosyltransferase function. This is the first time that the initiation enzyme of S-layer glycoprotein glycan biosynthesis in a gram-positive organism has been characterized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a was obtained from F. Hollaus (21) and grown on modified S-VIII medium (1% peptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% meat extract, 0.13% K2HPO4, 0.01% MgSO4, 0.06% sucrose) at 55°C. E. coli and S. enterica strains used in this study (Table 1) were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C. E. coli DH5α (Invitrogen, Lofer, Austria) was used for plasmid construction and replication. E. coli BL21(DE3) Star and E. coli TOP10 were used for protein overexpression. Growth media were supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), or gentamicin (30 μg/ml), when appropriate.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and/or relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) phoA supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 λ− | Invitrogen |

| BL21(λDE3) | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | Stratagene |

| BL21(λDE3) STAR | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm rne-131 | Stratagene |

| One Shot TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| C43(DE3) | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) C43 | 23 |

| CWG465 | B44 derivative, serotype O9:K30:H−; ΔlacZ::aphA3 Kmr | 30 |

| CWG466 | CWG465 derivative, serotype O9:K−:H−; ΔlacZ::aphA-3 wbaP::lacZ-aacC1 Kmr Gmr | 30 |

| S. enterica strains | ||

| LT2 | Serovar Typhimurium, wild-type isolate | Salmonella Genetic Stock Centre |

| MSS2 | LT2 ΔwbaP | 34 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET28a | E. coli expression vector; Kmr | Stratagene |

| pNGB200 | pET28a-WsaP (pET28a expressing WsaP [amino acids {aa} 1 to 471] from G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a); Kmr | |

| pNGB202 | pET28a-WsaP_B (pET28a expressing WsaP_B, devoid of the four N-terminal transmembrane domains [aa 168 to 471]); Kmr | |

| pBAD-DEST49 Gateway | Arabinose-inducible E. coli expression vector; Apr | Invitrogen |

| pNGB205 | pBAD-DEST49-WsaP (pBAD-DEST49 expressing WsaP); Apr | |

| pBluescript II SK(+) | Cloning vector; Apr | Stratagene |

| pNGB210 | pBluescript II SK(+) expressing WsaP (aa 1 to 471); Apr | |

| pNGB211 | pBluescript II SK(+) expressing WsaP_N, devoid of the C terminus (aa 1 to 314); Apr | |

| pNGB212 | pBluescript II SK(+) expressing WsaP_B, devoid of the four N-terminal transmembrane domains (aa 168 to 471); Apr | |

| pNGB213 | pBluescript II SK(+) expressing WsaP_C, devoid of all transmembrane domains (aa 311 to 471); Apr | |

| pWQ195 | wbaP and flanking sequence cloned as a 1.5-kbp fragment in pBluescript; Apr | C. Whitfield, unpublished data |

Sequence analysis.

Protein sequences were analyzed using the BLASTP online sequence homology analysis tools (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD). Putative transmembrane helices were identified with the TMHMM2.0 program (Center for Biological Sequence Analysis, Lyngby, Denmark). Sequence alignments were carried out with the ClustalW program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/).

Standard molecular techniques.

Genomic DNA of G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a was isolated with a QIAGEN Genomic-Tip 100 kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Restriction enzymes, calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase, and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from Invitrogen. A QIAGEN MinElute gel extraction kit was used to purify DNA fragments from agarose gels, and a QIAGEN MinElute reaction cleanup kit was used to purify digested oligonucleotides and plasmids. Plasmid DNA from transformed cells was isolated with a QIAGEN plasmid miniprep kit. Agarose gel electrophoresis was performed as described by Sambrook et al. (35). PCR (PCR Sprint thermocycler; Hybaid, Ashford, United Kingdom) was performed using Pwo polymerase (Roche, Vienna, Austria). PCR conditions were optimized for each primer pair, and amplification products were purified using a QIAGEN MinElute PCR purification kit. E. coli transformation was done according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Transformants were screened by in situ PCRs using RedTaq ReadyMix PCR mix (Sigma-Aldrich, Vienna, Austria); recombinant clones were analyzed by restriction mapping and confirmed by sequencing (Agowa, Berlin, Germany).

Construction of plasmids and strains.

Various plasmids for overexpression and complementation in E. coli were constructed (Table 1). The sequences of the oligonucleotide primers are listed in Table 2. To construct WsaP derivatives with N-terminal hexahistidine tags, the entire coding sequence and the C-terminal part of WsaP were amplified by PCRs with the primer pairs pET-WsaP_for/pET-WsaP_rev (WsaP) and pET-WsaP_B_for/pET-WsaP_rev (WsaP_B), respectively. Amplification products were digested with NdeI/XhoI and inserted into the dephosphorylated expression vector pET28a (Novagen, Madison, WI), which was linearized with the same restriction enzymes. The resulting plasmids, named pNGB200 (pET28a-WsaP) and pNGB202 (pET28a-WsaP_B), were verified by sequencing (Table 1). These constructs were transformed into the E. coli expression host BL21(DE3) Star for subcellular localization of the expressed protein via the introduced His tag. The pBAD-DEST49 expression system (Invitrogen) was used to produce a recombinant protein with horseradish peroxide-thioredoxin as an N-terminal fusion partner of the cloned gene product and a hexahistidine tag as a C-terminal fusion partner. PCR amplification of WsaP was accomplished with the oligonucleotides gWsaP_for and gWsaP_rev, containing attB1 and attB2 sites, for Gateway cloning by recombination (Invitrogen). After the generation of entry clones in plasmid pDONR-221 (Invitrogen), a second recombination reaction was performed with pBAD-DEST49. The vector construct was designated pNGB205 (pBAD-DEST49-WsaP), sequenced to ensure that no mutations were introduced, and transformed into E. coli TOP10.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used for PCR amplification of different forms of WsaP

| Primer and | Nucleotide sequence (5′→3′)a |

|---|---|

| plasmid target | |

| pET28a | |

| pET-WsaP_for | AATCACCATATGGTTAAGGTGATTAGAGGA AGA |

| pET-WsaP_B_for | AATCACCATATGGATCCGGAATTCGGG |

| pET-WsaP_C_for | AATCACCATATGGCTGGTCCGATTATTTTTAAACAAG |

| pET-WsaP_rev | ATAAGAATCTCGAGCTAATATGCATTTTTATTTACCAAACC |

| pBAD-DEST49 | |

| gWsaP_for | attB1-TCGTGGTTAAGGTGATTAGAGGAAGAG |

| gWsaP_rev | attB2-AATATGCATTTTTATTTACCAAACCATT |

| pBluescript SK II (+) | |

| WsaP_for | AATCAGAGCTCATTTGAACGAACCGCATCC |

| WsaP_rev | AATCACTGCAGAACACCCCATCTTCTAACA |

| WsaP_B_for | AATCAGAGCTCATGCATCCGGAATTCGGGT |

| WsaP_C_for | AATCAGAGCTCATGCCTGGTCCGATTATTTTTAAACAAG |

| WsaP_N_rev | AATCACTGCAGTCACTTGTTTAAAAATAAT |

The triplets corresponding to the initiation and termination codons in the primer sequences are shown in bold. Artificial restriction sites are underlined.

The plasmids for complementation studies were constructed as follows. Various fragments of WsaP were amplified by PCRs using the primer pairs WsaP_for/WsaP_rev (WsaP), WsaP_B_for/WsaP_rev (WsaP_B), WsaP_C_for/WsaP_rev (WsaP_C), and WsaP_for/WsaP_N_rev (WsaP_N), introducing artificial SstI and PstI restriction sites, and cloned into the SstI/PstI-linearized and dephosphorylated cloning vector pBluescript II SK(+) (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The resulting complementation plasmids were named pNGB210 (full WsaP), pNGB211 (N-terminal part of WsaP), pNGB212 (C-terminal part of WsaP, including the central transmembrane [TM] domain), and pNGB213 (C-terminal part of WsaP lacking the central TM domain) and sequenced (Table 1). The complementation plasmids were subsequently introduced into the mutant strains E. coli CWG466 and S. enterica MSS2 by electroporation.

Protein overexpression.

Synthesis of recombinant proteins in E. coli BL21(DE3) Star and TOP10 cells was initiated by the addition of 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) and 0.002% l-(+)-arabinose, respectively, to cultures at an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.8, and cultivation was continued for an additional 4 h. In an attempt to enhance the expression of WsaP forms containing TM domains, the BL21(DE3) mutant strain C43(DE3) was also used (23). This strain overproduces membranes in the cytoplasm. Expression of recombinant proteins was monitored by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (20). Protein bands were visualized with the Coomassie blue R-250 staining reagent. Semidry blotting in a discontinuous buffer system (54) at a constant current of 0.8 mA/cm2, using a Multiphor Novablot apparatus (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden), was performed to transfer the proteins to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Vienna, Austria). Anti-His-tag monoclonal antibody was purchased from Novagen, and antithioredoxin monoclonal antibody was obtained from Invitrogen. Development of the blot was accomplished according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Membrane preparation.

The preparation protocol essentially followed the method described by Osborn et al. (26), with slight modifications. The biomass from 400-ml cultures of E. coli containing expression or complementation constructs was harvested by centrifugation (15 min at 4,500 × g and 4°C) and washed with 100 ml of cold saline. The pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of cold buffer A (50 mM Tris-acetate, pH 8.5, 1 mM EDTA). The cells were lysed by ultrasonication (Branson sonifier 450; Branson, Danbury, CT) (duty cycle, 60%; output, 6), applying eight cycles of 10 pulses, with 1-min breaks. Unlysed cells were removed by centrifugation at 4,500 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and inclusion bodies were removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g (5). The membrane fraction was collected from the cell-free lysate by ultracentrifugation at 200,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C. The resulting membrane pellet was washed once with buffer A, centrifuged again, and finally resuspended in buffer A with gentle stirring for 30 min on ice. Aliquots containing approximately 1.5 mg of membrane protein were stored at −70°C until they were used. Protein concentrations in the membrane fractions were determined using the Bio-Rad Bradford reagent (3).

Purification of recombinant WsaP.

Isolated membranes were extracted on ice for 1 h with a cellular and organelle membrane solubilizing reagent (Sigma). After centrifugation at 20,800 × g for 1 h, the protein contents of the supernatants were determined using the Bio-Rad Bradford reagent. The extracted WsaP protein was purified by the batch method with His-Select nickel affinity gel (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's protocol. All buffers contained 0.1 mM of lauryldimethylamine N-oxide to keep WsaP in solution.

Glycosyltransferase activity assays.

In vitro glycosyltransferase assays were based on previously described methods (19, 40). The standard in vitro reaction mixture contained membranes (corresponding to 1.5 mg of protein) and 84 pmol (25 nCi) of radiolabeled UDP-d-[14C]galactose (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) in a total volume of 100 μl of buffer B (50 mM Tris-acetate, pH 8.5, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2). The reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 1.25 ml of chloroform (C)-methanol (M) (3:2) (11). After being shaken for 20 min, the samples were centrifuged, and the organic phases were transferred to a new tube. The pellet was reextracted with 1.35 ml of C-M-water (W) (3:2:0.4). The organic phases were washed with 150 μl of 40 mM MgCl2. The upper phase obtained after centrifugation was removed, and the lower organic phase was washed twice with 400 μl of pure-solvent upper-phase C-M-W-1 M MgCl2 (18:294:282:1). The organic phases containing the lipid-linked reaction products were combined and dried under nitrogen. The dried samples were resuspended in 10 μl of C-M (3:2) and applied to thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates. The lipid-linked products were separated on silica gel 60 aluminum TLC plates (20 by 20 cm; thickness, 0.25 mm; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) or silica gel 60 glass high-performance TLC plates (10 by 20 cm; thickness, 0.2 mm; Merck), routinely using the solvent system C-M-W (65:25:4). For autoradiography, the plates were exposed for 2 days at −70°C to Kodak BioMax MS film (Sigma).

LPS analysis.

LPS was isolated and analyzed by proteinase K digestion of whole-cell lysates following the method of Hitchcock and Brown (15), with slight modifications (40). Briefly, cells from 1 ml of an overnight culture, diluted to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0, were collected, washed with 0.84% saline, and resuspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, containing 2% [wt/vol] SDS, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, and bromophenol blue). The samples were boiled for 45 min prior to digestion with proteinase K at a final concentration of 0.5 μg/ml for 16 h at 55°C. LPS preparations were separated in standard SDS-PAGE gels (20) and visualized by silver staining (47) for carbohydrates. For Western immunoblotting, LPS separated by SDS-PAGE was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany) (46), using a Mini Trans-Blot cell (Bio-Rad). The blot was developed using anti-K30 serum as described elsewhere (7).

NMR spectroscopy.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded at 30°C in D2O on a Varian UNITY INOVA 500 instrument, using acetone as a reference for proton (2.225 ppm) and carbon (31.5 ppm) spectra. Varian standard programs COSY, NOESY (mixing time of 200 ms), TOCSY (spin-lock time of 120 ms), HSQC, and gHMBC (long-range transfer delay of 100 ms) were used.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sequence analysis of WsaP.

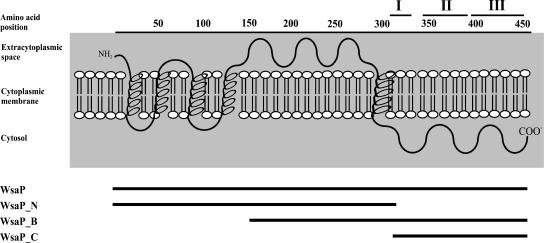

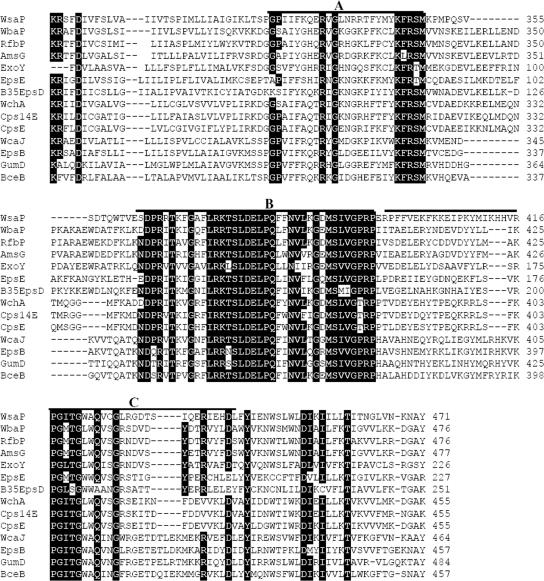

The deduced 471-amino-acid sequence of WsaP encoded in the slg gene cluster of G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a exhibits high homology (∼31% similarity and 47% identity) to members of the polyisoprenyl-phosphate hexose-1-phosphate transferase (PHPT) family, which transfer hexose-1-P residues from UDP-hexoses to a lipid carrier (1, 8, 18, 25, 27, 44, 49, 52). The topological model of WsaP (Protein Data Bank accession number AAR99615) shows five TM domains (four clustered in the N terminus of the protein and one towards the C terminus) and two large loops (a large central loop of approximately 150 amino acids and a large C-terminal cytosolic tail containing the putative catalytic domain), which is typical of PHPTs (49) (Fig. 1). The C terminus is highly conserved among the members of this enzyme family (Fig. 2). Three blocks with the highly conserved amino acid stretches KFRSM, DELPQ, and PGITG, characteristic of blocks I, II, and III, respectively, are usually found in the C-terminal halves of PHPT proteins (53). The significant amino acid homology of WsaP with WbaP suggests that these proteins may be functionally similar.

FIG. 1.

Predicted topology of the WsaP protein of G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a as a basis for designing different forms of WsaP to assess the functional domains of the enzyme. WsaP, aa 1 to 471 (full size); WsaP_N, aa 1 to 314, including all transmembrane domains but lacking the C terminus; WsaP_B, aa 168 to 471, including one transmembrane domain and the putative catalytic domain; WsaP_C, aa 311 to 471, including the putative catalytic domain but lacking all transmembrane domains. I, II, and III designate the blocks of conserved amino acid stretches in PHPT proteins.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of conserved PF02397 C-terminal region of WsaP from G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a with other members of the PHPT family. The galactosyltransferases compared were as follows: E. coli WbaP (accession number AAD21565), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium WbaP (formerly RfbP; accession number P26406), Erwinia amylovora AmsG (accession number Q46628), Sinorhizobium meliloti ExoY (accession number Q02731), Streptococcus thermophilus EpsE (accession number AAC44012), and Lactococcus lactis B35 EpsD (accession number AAD22526). The glucosyltransferases compared were as follows: Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 8 WchA (accession number AAK20699), S. pneumoniae Cps14E (accession number CAA59777), Streptococcus salivarius CpsE (accession number CAC18355), E. coli WcaJ (accession number AP_002647), Methylobacillus sp. strain 12S EpsB (accession number BAC41337), Xanthomonas campestris GumD (accession number AAA86372), and Burkholderia cenocepacia IST432 BceB (accession number ABC71344).

Expression and subcellular localization of WsaP in E. coli.

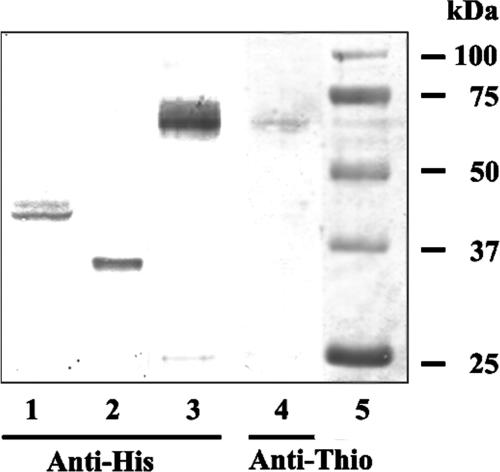

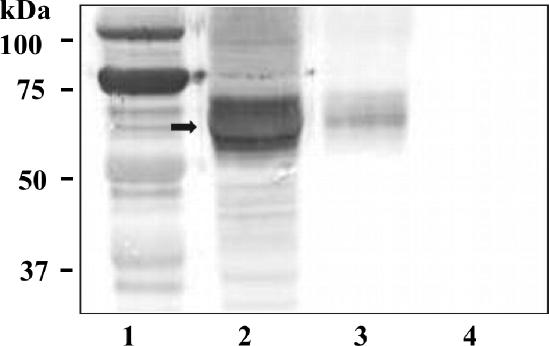

Overexpression of the recombinant N-terminally His-tagged proteins WsaP (pNGB200) and WsaP_B (pNGB202), with expected masses of 56.8 and 36.5 kDa, respectively, was monitored by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. In SDS-PAGE, the full-length protein was not visible upon Coomassie staining. In Western blot analysis, the proteins could be detected using an anti-His-tag antibody. The apparent mass of the full-length protein was ∼15 kDa smaller than expected (Fig. 3, lane 1), but the truncated versions lacking the four N-terminal transmembrane domains (WsaP_B) or even all transmembrane domains (WsaP_C) yielded proteins displaying the expected masses on the gel. Data for WsaP_B are shown in Fig. 3 (lane 2). To verify that WsaP was expressed as a full-length protein, the gene was cloned into the pBAD-DEST49 vector to introduce a thioredoxin tag at the N terminus and a His tag at the C terminus of the protein, resulting in a protein with an expected mass of 72.87 kDa. Western blot analysis was performed with anti-His-tag and antithioredoxin antibodies. The observed mass of the protein was still smaller than expected, but since both tags were detectable, it is evident that the complete protein was expressed and no protein degradation or processing took place (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 4). The phenomenon of changed migration behavior on SDS-PAGE gels has been reported for other glycosyltransferases possessing transmembrane domains, e.g., WbaP (53) and WchA (27), and also for membrane proteins in general (33). This may be due to the hydrophobicity of the transmembrane domain, a high binding capacity for SDS, or the retention of secondary structure accelerating passage through the gel. Furthermore, quite frequently the overexpression of membrane proteins, as is also the case for full-length WsaP, results in a low protein yield (2). E. coli C43(DE3) is a mutant strain of E. coli BL21(DE3) that overproduces membranes (23). However, no increase of expression of WsaP was observed when this strain was used (data not shown). Due to their hydrophobicity, recombinant membrane proteins can be expressed in E. coli either in the cytoplasmic membrane or as inclusion bodies. The subcellular localization of WsaP in E. coli was assessed by differential centrifugation of crude cell extracts obtained by sonic disruption of E. coli TOP10 cells harboring plasmid pNGB205. The contents of each fraction were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-His-tag antibody. The majority of overexpressed WsaP was detected in the membrane fraction (Fig. 4, lane 3). No inclusion bodies were observed by electron microscopy (data not shown). After numerous attempts with different detergents and affinity chromatography materials, we succeeded in extracting and purifying small amounts (125 μg/liter) of WsaP. However, according to an in vitro galactosyltransferase assay, the enzyme activity of this preparation was lost, suggesting that a lipid environment is necessary for the enzymatic activity of WsaP or that the enzyme loses critical folding properties during purification.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of the expression of WsaP and WsaP_B in E. coli, using different expression systems. The expressed proteins were detected by either anti-His-tag (lanes 1 to 3) or antithioredoxin (lane 4) antibody. WsaP (lane 1) and WsaP_B (lane 2) were expressed using the expression vector pET28a in E. coli BL21(DE3) Star. WsaP was additionally cloned into the pBAD-DEST49 expression system and expressed in E. coli TOP10 cells (lanes 3 and 4). The Precision Plus All Blue protein standard (Bio-Rad) is displayed in lane 5. Approximately 10 μg of total protein was loaded on the gel.

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of cellular fractions of E. coli TOP10 cells harboring the plasmid pNGB205 and expressing WsaP. Membranes were isolated by differential centrifugation. The protein (indicated by an arrow) was detected, using an anti-His-tag antibody, in the cells (lane 2) and in the membrane fraction (lane 3), whereas the cytosolic fraction (lane 4) was devoid of WsaP. Lane 1, Precision Plus All Blue protein standard (Bio-Rad).

Reconstitution of K antigen expression in E. coli and of O antigen synthesis in S. enterica.

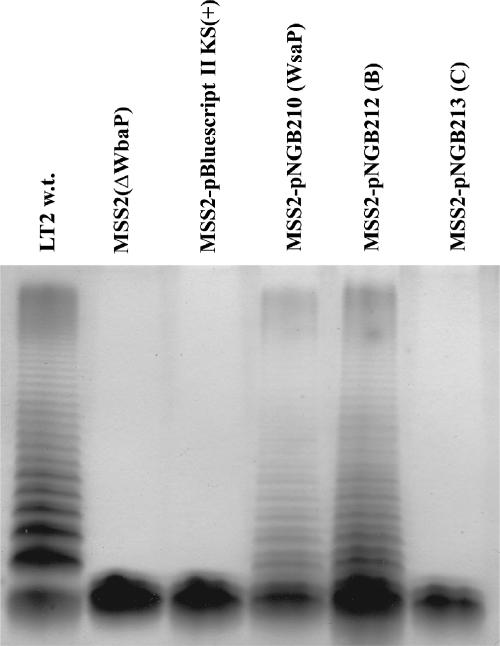

To characterize the initiation event of S-layer glycoprotein glycan biosynthesis in G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a, further studies of WsaP were carried out in gram-negative bacteria for which the biosynthesis pathways for the various glycans are well established and defined mutants with well-characterized defects are available. WsaP has high amino acid sequence and hydrophobicity similarities to WbaP. In E. coli, WbaP initiates the biosynthesis of the K30 antigen by transferring galactose-1-P from UDP-Gal to Und-P (8). The K30 antigen is representative of group 1 capsules, and its biosynthesis follows the Wzy-dependent pathway (55). To confirm the function of WsaP as a galactosyltransferase, we investigated whether WsaP is capable of reconstituting K30 antigen biosynthesis in the WbaP-deficient strain E. coli CWG466 (wbaP::lacZ-aacC1) (30). This strain also forms LPS with an O9-specific polysaccharide, a polymannan, whose biosynthesis is initiated by WecA. This protein is the prototype of another family of initiating transferases which have specificity for UDP-N-acetylglucosamine and other UDP-N-acetylated sugars (49). To determine which region of WsaP is responsible for transferase activity, truncated versions of the protein were generated (Fig. 1) for reconstitution experiments. WsaP and the truncated versions of WsaP were cloned into pBluescript II SK(+) and transformed into E. coli CWG466 (wbaP::lacZ-aacC1) O9:K−. LPS analysis by silver staining did not show any differences because the production of O9-specific LPS in CWG466 is intact and masks the K antigen (Fig. 5A). In contrast, a Western blot analysis with K30-specific antibodies revealed that biosynthesis of the K30 antigen was restored only with full-length WsaP (pNGB210) and WsaP_B (pNGB212) (Fig. 5B). The latter construct corresponds to a protein lacking the four predicted transmembrane domains of the N terminus (Fig. 1). As expected, pWQ195, encoding WbaP, complemented K30 production, while the vector control did not. Also, no complementation was observed for WsaP_C (pNGB213) and WsaP_N (pNGB211) (Fig. 5), which include the C-terminal domain without any transmembrane domains and the segment of the protein with all five predicted transmembrane domains, respectively (Fig. 1). From these data, we concluded that full-length WsaP and a truncated version with one transmembrane domain at the C terminus (WsaP_B) can complement the synthesis of K30 antigen, suggesting that these proteins are functionally equivalent to WbaP. To further support this conclusion, we also performed complementation experiments with S. enterica strain MSS2, which carries a deletion of wbaP that prevents O antigen synthesis (34). Figure 6 shows that only plasmids expressing WsaP and WsaP_B could complement O antigen synthesis in strain MSS2, while plasmids expressing the other constructs did not. Together, these experiments demonstrate that WsaP is a functional homologue of WbaP. Furthermore, as previously demonstrated for WbaP in S. enterica (53), the C-terminal region of WsaP and the last transmembrane domain appear to be required for catalytic activity.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of the surface polysaccharide phenotypes of E. coli CWG465 (O9:K30) and derivative strains CWG466 (O9:K−) and CWG466 (O9:K−) harboring different plasmids. The polysaccharides were examined in protease-digested whole-cell lysates. (A) Silver-stained SDS-PAGE gel. The production of O9-specific LPS in CWG466 is intact. Capsular K30 antigen was not detected by silver staining. (B) Western immunoblot, probed with adsorbed rabbit polyclonal antiserum specific for the K30 antigen.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of the lipopolysaccharide phenotypes of S. enterica LT2, MSS2, and MSS2 harboring different plasmids by silver-stained SDS-PAGE. The polysaccharides were examined in protease-digested whole-cell lysates. w.t., wild type.

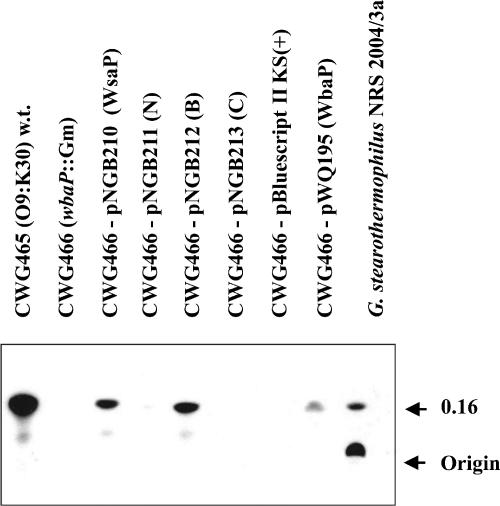

In vitro galactosyltransferase assay.

The proposed enzymatic activity of WsaP and its truncations was assayed by determining the incorporation of radioactive galactose into a lipid-linked biosynthesis intermediate. Membranes isolated from E. coli CWG465 and CWG466 containing different WsaP constructs and pWQ195 as a positive control were incubated with UDP-[14C]Gal as a substrate. In this assay, membranes served as a source of enzyme and also of the lipid acceptor. Membranes from E. coli CWG466 and CWG466 containing pBluescript II SK(+) were used as negative controls. After extraction of the lipid fraction, the products were separated on silica plates by TLC and visualized by autoradiography. Membranes containing WsaP and WsaP_B revealed a product with an Rf value of 0.16, which corresponds to the Rf value observed for membranes of G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a incubated with UDP-[14C]Gal (Fig. 7). As expected, the native WbaP protein in CWG465 and the plasmid-encoded WbaP protein in CWG466(pWQ195) also catalyzed the transfer of [14C]Gal to an endogenous acceptor. The data demonstrate that full-length WsaP and the N-terminally truncated version WsaP_B have galactosyltransferase activity and therefore are functionally identical to WbaP. In this context, it should be noted that in the case of G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a, a second spot can be visualized by autoradiography. Giving an interpretation of this compound would be unnecessarily speculative, as different lipid acceptors and epimerization of the UDP-sugar substrate may be involved in product formation in this gram-positive bacterium. To prove the WsaP dependence of the second compound, a knockout mutant would be required; however, this currently cannot be accomplished due to the intransformability of G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a.

FIG. 7.

TLC autoradiogram showing lipid carrier-linked intermediates synthesized in an in vitro assay of membranes isolated from E. coli CWG466 containing the different WsaP constructs and from G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a. The products were separated on silica plates by TLC, using the solvent system C-M-W (65:25:4). w.t., wild type.

NMR analysis.

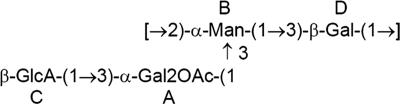

To confirm that the structure of the K30 antigen is the same in the complemented strain CWG466(pNGB210) as in the wild-type strain CWG465, CPS was isolated and analyzed by NMR (Table 3; Fig. 8). No difference in the CPS structures of the two strains was observed. The structure corresponds to the already published structure of the K30 antigen (4), with the minor difference that about 30% of α-galactose is O-acetylated.

TABLE 3.

1H- and 13C-NMR chemical shifts of the capsular polysaccharide K30 of E. coli CWG465 and E. coli CWG466(pNGB210)a

| Unitb | Nucleus | Signal (ppm) at position

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6, 6′ | ||

| A | 1H | 5.38 | 4.01 | 4.02 | 4.23 | 4.23 | 3.66, 3.86 |

| 13C | 101.4 | 69.1 | 81.3 | 70.8 | 72.6 | 60.4, 61.6 | |

| A′ | 1H | 5.44 | 5.12 | 4.21 | 4.26 | 4.31 | 3.66, 3.86 |

| 13C | 99.2 | 71.3 | 78.1 | 71.0 | 72.7 | 60.4, 61.6 | |

| B | 1H | 5.17 | 4.31 | 4.20 | 3.94 | 3.96 | 3.66, 3.86 |

| 13C | 95.6 | 78.4 | 75.6 | 67.9 | 74.0 | 60.4, 61.6 | |

| B′ | 1H | 5.17 | 4.31 | 4.15 | 3.94 | 3.92 | 3.66, 3.86 |

| 13C | 95.6 | 78.4 | 76.3 | 67.9 | 74.5 | 60.4, 61.6 | |

| C | 1H | 4.72 | 3.44 | 3.55 | 3.55 | 3.87 | |

| 13C | 105.5 | 74.5 | 76.6 | 73.1 | 76.9 | ||

| C′ | 1H | 4.72 | 3.35 | 3.55 | 3.55 | 3.87 | |

| 13C | 105.5 | 74.0 | 76.6 | 73.1 | 76.9 | ||

| D, D′ | 1H | 4.54 | 3.69 | 3.76 | 4.19 | 3.64 | 3.66, 3.86 |

| 13C | 103.4 | 70.5 | 77.8 | 65.7 | 76.2 | 60.4, 61.6 | |

For the structure of the polysaccharide, see Fig. 8.

Residues marked with a prime symbol are from acetylated repeating units. O-acetylated signals were 2.16 ppm (1H) and 21.7 ppm (13C).

FIG. 8.

Structure of the K30 repeat unit of E. coli CWG465 and CWG466(pNGB210), which is identical to that already published (4), except for the minor difference that about 30% of α-galactose is O-acetylated. For the assignment of glycoses A, B, C, and D, see Table 3.

Concluding remarks.

The genetic, biochemical, and structural data in the present study clearly demonstrate that WsaP is the initiating galactosyltransferase for S-layer glycoprotein glycan biosynthesis in G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a. Moreover, we could prove that the catalytic domain is located in the C terminus of the protein.

The presence of a predicted ABC-2-type transporter system and the absence of a putative polymerase in the slg gene cluster of G. stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a (25) indicate that the S-layer glycan chains are most probably synthesized in a process comparable to the ABC transporter-dependent pathway of LPS O-polysaccharide biosynthesis, although being initiated by a WbaP homologue instead of a WecA homologue, which usually serves as the initiation enzyme in that pathway (29). Our current model implicates WsaP in the first step of synthesis whereby galactose is transferred from its nucleotide-activated form (UDP-Gal) to a membrane-associated lipid carrier at the cytoplasmic face of the plasma membrane. Chain extension presumably would continue in the cytoplasm by processive addition of nucleotide-activated dTDP-β-l-rhamnose residues to the nonreducing terminus of the lipid-linked glycan chain. Chain growth is predicted to terminate by 2-O-methylation of the terminal repeating unit, catalyzed by an O-methyltransferase (39). A similar modification was recently described as a chain length termination signal in the biosynthesis of O8 and O9 antigens (6). The complete glycan chain would then be transported across the membrane by a process involving an ABC transporter and transferred to the S-layer protein. Undecaprenol phosphate is recognized as an acceptor molecule for WsaP in the E. coli background, which is a necessary prerequisite for combining S-layer protein O-glycosylation and LPS biosynthesis pathways in glycoengineering applications.

Ultimately, we expect that a detailed understanding of the glycosyltransferases involved in S-layer glycan biosynthesis, in combination with the self-assembly properties of S-layer proteins, will enable the design of highly regular arrays of S-layer neoglycoproteins with spatial control of glycan presentation as therapeutics, glycan-based vaccines, or nutritional supplements.

Acknowledgments

We thank Soledad Saldías for providing Salmonella strain MSS2.

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund under projects P15840-B10, P18013-B10 (both to P.M.), and P19047-B12 (to C.S.), by the Hochschuljubiläumsstiftung der Stadt Wien under project H949/2004 (to K.S.), and by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to M.A.V.). M.A.V. holds a Canada Research Chair in Infectious Diseases and Microbial Pathogenesis. C.W. holds a Canada Research Chair in Molecular Microbiology and acknowledges research funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 January 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almirón-Roig, E., F. Mulholland, M. J. Gasson, and A. M. Griffin. 2000. The complete cps gene cluster from Streptococcus thermophilus NCFB 2393 involved in the biosynthesis of a new exopolysaccharide. Microbiology 146:2793-2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arechaga, I., B. Miroux, S. Karrasch, R. Huijbregts, B. de Kruijff, M. J. Runswick, and J. E. Walker. 2000. Characterisation of new intracellular membranes in Escherichia coli accompanying large scale over-production of the b subunit of F(1)F(o) ATP synthase. FEBS Lett. 482:215-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakraborty, A. K., H. Friebolin, and S. Stirm. 1980. Primary structure of the Escherichia coli serotype K30 capsular polysaccharide. J. Bacteriol. 141:971-972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charbonnier, F., T. Köhler, J. C. Pechere, and A. Ducruix. 2001. Overexpression, refolding, and purification of the histidine-tagged outer membrane efflux protein OprM of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein Expr. Purif. 23:121-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke, B. R., L. Cuthbertson, and C. Whitfield. 2004. Nonreducing terminal modifications determine the chain length of polymannose O antigens of Escherichia coli and couple chain termination to polymer export via an ATP-binding cassette transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 279:35709-35718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodgson, C., P. Amor, and C. Whitfield. 1996. Distribution of the rol gene encoding the regulator of lipopolysaccharide O-chain length in Escherichia coli and its influence on the expression of group I capsular K antigens. J. Bacteriol. 178:1895-1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drummelsmith, J., and C. Whitfield. 1999. Gene products required for surface expression of the capsular form of the group 1 K antigen in Escherichia coli (O9a:K30). Mol. Microbiol. 31:1321-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eichler, J., and M. M. W. Adams. 2005. Posttranslational protein modification in archaea. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69:393-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman, M. F., M. Wacker, M. Hernandez, P. G. Hitchen, C. L. Marolda, M. Kowarik, H. R. Morris, A. Dell, M. A. Valvano, and M. Aebi. 2005. Engineering N-linked protein glycosylation with diverse O antigen lipopolysaccharide structures in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:3016-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folch, J., M. Lees, and G. H. Sloane-Stanley. 1957. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226:497-509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grabenhorst, E., P. Schlenke, S. Pohl, M. Nimtz, and H. S. Conradt. 1999. Genetic engineering of recombinant glycoproteins and the glycosylation pathway in mammalian host cells. Glycoconj. J. 16:81-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graninger, M., B. Kneidinger, K. Bruno, A. Scheberl, and P. Messner. 2002. Homologs of the Rml enzymes from Salmonella enterica are responsible for dTDP-β-l-rhamnose biosynthesis in the gram-positive thermophile Aneurinibacillus thermoaerophilus DSM 10155. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3708-3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartmann, E., P. Messner, G. Allmaier, and H. König. 1993. Proposed pathway for biosynthesis of the S-layer glycoprotein of Bacillus alvei. J. Bacteriol. 175:4515-4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hitchcock, P. J., and T. M. Brown. 1983. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J. Bacteriol. 154:269-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hitchen, P. G., and A. Dell. 2006. Bacterial glycoproteomics. Microbiology 152:1575-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kneidinger, B., C. Marolda, M. Graninger, A. Zamyatina, F. McArthur, P. Kosma, M. A. Valvano, and P. Messner. 2002. Biosynthesis pathway of ADP-l-glycero-β-d-manno-heptose in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:363-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolkman, M. A., D. A. Morrison, B. A. van der Zeijst, and P. J. Nuijten. 1996. The capsule polysaccharide synthesis locus of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 14: identification of the glycosyl transferase gene cps14E. J. Bacteriol. 178:3736-3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolkman, M. A., B. A. van der Zeijst, and P. J. Nuijten. 1997. Functional analysis of glycosyltransferases encoded by the capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis locus of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 14. J. Biol. Chem. 272:19502-19508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messner, P., F. Hollaus, and U. B. Sleytr. 1984. Paracrystalline cell wall surface layers of different Bacillus stearothermophilus strains. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 34:202-210. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Messner, P., and C. Schäffer. 2003. Prokaryotic glycoproteins. Fortschr. Chem. Org. Naturst. 85:51-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miroux, B., and J. E. Walker. 1996. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J. Mol. Biol. 260:289-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novotny, R., A. Pföstl, P. Messner, and C. Schäffer. 2004. Genetic organization of chromosomal S-layer glycan biosynthesis loci of Bacillaceae. Glycoconj. J. 20:435-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novotny, R., C. Schäffer, J. Strauss, and P. Messner. 2004. S-layer glycan-specific loci on the chromosome of Geobacillus stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a and dTDP-l-rhamnose biosynthesis potential of G. stearothermophilus strains. Microbiology 150:953-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osborn, J. N., M. A. Cynkin, J. M. Gilbert, L. Müller, and M. Singh. 1972. Synthesis of bacterial O-antigens. Methods Enzymol. 28:583-601. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelosi, L., M. Boumedienne, N. Saksouk, J. Geiselmann, and R. A. Geremia. 2005. The glucosyl-1-phosphate transferase WchA (Cap8E) primes the capsular polysaccharide repeat unit biosynthesis of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 8. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 327:857-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pföstl, A., A. Hofinger, P. Kosma, and P. Messner. 2003. Biosynthesis of dTDP-3-acetamido-3,6-dideoxy-α-d-galactose in Aneurinibacillus thermoaerophilus L420-91T. J. Biol. Chem. 278:26410-26417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raetz, C. R. H., and C. Whitfield. 2002. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71:635-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rahn, A., and C. Whitfield. 2003. Transcriptional organization and regulation of the Escherichia coli K30 group 1 capsule biosynthesis (cps) gene cluster. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1045-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reeves, P. R., M. Hobbs, M. A. Valvano, M. Skurnik, C. Whitfield, D. Coplin, N. Kido, J. Klena, D. Maskell, C. R. H. Raetz, and P. D. Rick. 1996. Bacterial polysaccharide synthesis and gene nomenclature. Trends Microbiol. 4:495-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudd, P. M., T. Elliott, P. Cresswell, I. A. Wilson, and R. A. Dwek. 2001. Glycosylation and the immune system. Science 291:2370-2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saidijam, M., G. Psakis, J. L. Clough, J. Meuller, S. Suzuki, C. J. Hoyle, S. L. Palmer, S. M. Morrison, M. K. Pos, R. C. Essenberg, M. C. Maiden, A. Abu-Bakr, S. G. Baumberg, A. A. Neyfakh, J. K. Griffith, M. J. Stark, A. Ward, J. O'Reilly, N. G. Rutherford, M. K. Phillips-Jones, and P. J. Henderson. 2003. Collection and characterisation of bacterial membrane proteins. FEBS Lett. 555:170-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saldías, M. S. 2004. Functional analysis of WbaP, essential enzyme in the biosynthesis of O-antigen in Salmonella enterica. Ph.D. thesis. Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile.

- 35.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 36.Samuel, G., and P. Reeves. 2003. Biosynthesis of O-antigens: genes and pathways involved in nucleotide sugar precursor synthesis and O-antigen assembly. Carbohydr. Res. 338:2503-2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saxon, E., and C. R. Bertozzi. 2001. Chemical and biological strategies for engineering cell surface glycosylation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17:1-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schäffer, C., T. Wugeditsch, C. Neuninger, and P. Messner. 1996. Are S-layer glycoproteins and lipopolysaccharides related? Microb. Drug Resist. 2:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schäffer, C., T. Wugeditsch, H. Kählig, A. Scheberl, S. Zayni, and P. Messner. 2002. The surface layer (S-layer) glycoprotein of Geobacillus stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a. Analysis of its glycosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:6230-6239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schäffer, C., T. Wugeditsch, P. Messner, and C. Whitfield. 2002. Functional expression of enterobacterial O-polysaccharide biosynthesis enzymes in Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4722-4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schäffer, C., and P. Messner. 2004. Surface-layer glycoproteins: an example for the diversity of bacterial glycosylation with promising impacts on nanobiotechnology. Glycobiology 14:31R-42R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sleytr, U. B., M. Sára, D. Pum, B. Schuster, P. Messner, and C. Schäffer. 2002. Self-assembly protein systems: microbial S-layers, p. 285-338. In A. Steinbüchel and S. R. Fahnestock (ed.), Biopolymers, vol. 7. Polyamides and complex proteinaceous matrices. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steiner, K., G. Pohlentz, K. Dreisewerd, S. Berkenkamp, P. Messner, J. Peter-Katalinic, and C. Schäffer. 2006. New insights into the glycosylation of the surface layer protein SgsE from Geobacillus stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a. J. Bacteriol. 188:7914-7921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stingele, F., J. W. Newell, and J. R. Neeser. 1999. Unraveling the function of glycosyltransferases in Streptococcus thermophilus Sfi6. J. Bacteriol. 181:6354-6360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szymanski, C. M., and B. W. Wren. 2005. Protein glycosylation in bacterial mucosal pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:225-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsai, C. M., and C. E. Frasch. 1982. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 119:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Upreti, R. K., M. Kumar, and V. Shankar. 2003. Bacterial glycoproteins: functions, biosynthesis and applications. Proteomics 3:363-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valvano, M. A. 2003. Export of O-specific lipopolysaccharide. Front. Biosci. 8:S452-S471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varki, A., R. Cummings, J. Esko, H. Freeze, G. Hart, and J. Marth (ed.). 1999. Essentials of glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [PubMed]

- 51.Wacker, M., D. Linton, P. G. Hitchen, M. Nita-Lazar, S. M. Haslam, S. J. North, M. Panico, H. R. Morris, A. Dell, B. W. Wren, and M. Aebi. 2002. N-linked glycosylation in Campylobacter jejuni and its functional transfer into E. coli. Science 298:1790-1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang, L., and P. R. Reeves. 1994. Involvement of the galactosyl-1-phosphate transferase encoded by the Salmonella enterica rfbP gene in O-antigen subunit processing. J. Bacteriol. 176:4348-4356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang, L., D. Liu, and P. R. Reeves. 1996. C-terminal half of Salmonella enterica WbaP (RfbP) is the galactosyl-1-phosphate transferase domain catalyzing the first step of O-antigen synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 178:2598-2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Westermeier, R. 1990. Electrophoresis—Praktikum, p. 189-196. VCH Verlagsgesellschaft, Weinheim, Germany.

- 55.Whitfield, C. 2006. Biosynthesis and assembly of capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75:39-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]