Abstract

The cytoplasmic membrane protein TonB couples the protonmotive force of the cytoplasmic membrane to active transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. The uncleaved amino-terminal signal anchor transmembrane domain (TMD; residues 12 to 32) of TonB and the integral cytoplasmic membrane proteins ExbB and ExbD are essential to this process, with important interactions occurring among the several TMDs of all three proteins. Here, we show that, of all the residues in the TonB TMD, only His20 is essential for TonB activity. When alanyl residues replaced all TMD residues except Ser16 and His20, the resultant “all-Ala Ser16 His20” TMD TonB retained 90% of wild-type iron transport activity. Ser16Ala in the context of a wild-type TonB TMD was fully active. In contrast, His20Ala in the wild-type TMD was entirely inactive. In more mechanistically informative assays, the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB unexpectedly failed to support formation of disulfide-linked dimers by TonB derivatives bearing Cys substitutions for the aromatic residues in the carboxy terminus. We hypothesize that, because ExbB/D apparently cannot efficiently down-regulate conformational changes at the TonB carboxy terminus through the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD, the TonB carboxy terminus might fold so rapidly that disulfide-linked dimers cannot be efficiently trapped. In formaldehyde cross-linking experiments, the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD also supported large numbers of apparently nonspecific contacts with unknown proteins. The all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB retained its dependence on ExbB/D. Together, these results suggest that a role for ExbB/D might be to control rapid and nonspecific folding that the unregulated TonB carboxy terminus otherwise undergoes. Such a model helps to reconcile the crystal/nuclear magnetic resonance structures of the TonB carboxy terminus with conformational changes and mutant phenotypes observed at the TonB carboxy terminus in vivo.

The gram-negative envelope is characterized by two concentric membranes, the inner or cytoplasmic membrane (CM) and an outer, asymmetric lipopolysaccharide and phospholipid leaflet known as the outer membrane (OM). This OM retards the passage of various hydrophobic toxins and yet allows diffusion of hydrophilic nutrients through aqueous channels provided by porin proteins. While most of the metabolic demands of gram-negative bacteria can be met by diffusible nutrients, iron demand presents a complication. In neutral oxidizing environments, bioavailable iron is limiting. To obtain it, most microbes rely upon the synthesis and secretion of high-affinity iron chelators called siderophores to capture ferric ions. Because the resultant iron-siderophore complexes exceed the diffusion limit of the OM, efficient iron retrieval depends on transporters with subnanomolar affinities for the siderophores.

Release (transport) of the tightly bound ligand into the periplasmic space requires energy. Because envelope physiology and architecture preclude energy production at the OM, these transporters must rely upon imported energy. The source of this energy is the CM protonmotive force (pmf)—or something coupled to it—as apparently harvested by heteromultimeric complexes of ExbB and ExbD proteins and transduced to the OM high-affinity vitamin B12 and siderophore transporters by the TonB protein (see references 42 and 52 for recent reviews). In addition to iron siderophores, TonB-transduced energy has long been known to be essential for the high-affinity transport of cobalamin (1, 2), with recent studies suggesting that TonB may indeed support the transport of a much wider range of ligands in certain species (9, 36).

Current data suggest that TonB transduces energy to OM transporters through direct and cyclic contact (reviewed in reference 43). The TonB protein is anchored by its amino terminus in a CM complex of ExbB and ExbD proteins that could be as large as 520 kDa (3, 13, 17, 18, 20, 22, 23, 46). The hydrophobic portion of the TonB amino terminus (residues 12 to 32) is called the transmembrane domain (TMD), although it probably never contacts membrane phospholipids after assembly into the ExbB/D complex. Nonetheless, the TonB TMD does serve as the signal sequence for Sec-dependent export (23, 44, 49) across the CM, with the result that the carboxy terminus of TonB (residues 33 to 239) occupies the aqueous periplasmic space between CM and OM (15, 45).

Previous work in our laboratory had indicated that the TonB TMD engages in specific interactions with the energy-harvesting ExbB/D complex that are essential for energy transduction. When modeled as an α-helix, one face of the TonB TMD is occupied by a set of residues conserved among various gram-negative enteric bacteria and shared with the TonB paralog TolA (Ser16, His20, Leu27, and Ser31) (25). Certain amino acid substitutions at two of these residues (Ser16 and His20) or alterations in their spatial relationship to each other render TonB unable to support active transport at the OM (31, 32). These mutant TonB derivatives appear to be nonenergizable by the ExbB/ExbD complex and do not undergo the pmf-dependent conformational change associated with energized TonB (32). This phenotype can be suppressed in a non-allele-specific manner by mutations that map near the cytoplasmic boundary of the first TMD of ExbB, restoring activity (and the energized conformation) to these TonB mutants (32, 33). Interestingly, TonB mutants that achieve an active state with the assistance of ExbB suppressors become susceptible to rapid proteolytic degradation following successful energy transduction to the OM transporters. Thus, it appears that Ser16Leu and His20Tyr substitutions interfere with efficient recycling following an energy transduction event (32).

The above-mentioned studies indicate that the TMD of TonB plays at least two roles in the energy transduction cycle: first, it participates in the acquisition of “energy” from the energy-harvesting ExbB/ExbD complex; second, it contributes to the efficient recycling of TonB following energy transfer to TonB-gated transporters. We decided to test the hypothesis that only TonB-Ser16 and -His20 are important for energy transduction by constructing a TMD devoid of all other functional side chains. Ala residues were substituted in the region of residues 12 to 32 at all positions other than Ser16 and His20 (this substitution is hereinafter referred to as “all-Ala Ser16 His20”). Here, we show that the retention of the Ser16 His20 motif alone, displayed on an all-alanyl scaffolding, was sufficient for the transduction of energy to TonB-gated OM transporters. Consistent with that observation, His20Ala on a wild-type scaffolding was inactive. In contrast, the activity of Ser16Ala on an otherwise wild-type scaffolding was unaltered. The stabilities of these TonB derivatives were only moderately affected. Together, these results suggest that the His20 motif is the only component of the TMD that conveys information significant to the energization of TonB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media.

Bacterial strains and plasmids were maintained on Luria-Bertani (LB) plates (35), containing chloramphenicol at 34 μg ml−1 where required. Cells for specific assays were grown in or on either tryptone (T) or M9 minimal medium (35), the latter supplemented with 0.4% (wt/vol) glycerol, a defined amino acid cocktail (40 μg ml−1 each, except aspartic acid and glutamic acid [30 μg ml−1 each] and tyrosine [10 μg ml−1]), 0.4 μg ml−1 thiamine, 1.0 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM CaCl2, and 1.85 μM iron (provided as FeCl3·6H2O). Media were also supplemented with l-arabinose as indicated.

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The principal strains and plasmids used are summarized in Table 1. All bacteria are derivatives of the Escherichia coli K-12 strain W3110 (21), except as noted. RA1024 carries a set of deletions assembled by sequential generalized transduction steps using bacteriophage P1vir (35). First, the ΔexbBD::kan strain RA1003 was produced using a strategy similar to that used to generate the ΔtonB::blaM strain KP1344 (32). Briefly, the gene to be deleted (in this case exbBD) and flanking regions (∼1 kb) are first cloned into a plasmid, with the gene itself then deleted by a subsequent, extra-long PCR as previously described (20), generating a unique restriction site into which the kan gene from pACYC177 was then inserted. This plasmid was then transformed into W3110 and a resultant ExbB/D− kanamycin-resistant homogenote isolated, with the absence of ExbB and ExbD proteins confirmed by immunoblot analysis (data not shown). Second, the ΔtolQRA strain RA1017 was produced using the λ-red recombinase approach of Datsenko and Wanner (7). Briefly, an amplimer bearing a kan gene nested between a pair of FLP recombination target sites and flanked by sequences homologous to the immediate upstream and downstream regions of tolQRA was introduced into the K-12 strain BW25113 and a kanamycin-resistant recombinant isolated. This deletion was moved into W3110 by P1 transduction, with the kan gene subsequently excised at the FLP recombination target sites by a plasmid-encoded FLP recombinase. This resultant strain (RA1017) then received the ΔtonB::blaM and ΔexbBD::kan mutations by sequential P1 transductions from KP1344 and RA1003, respectively.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| W3110 | F− IN(rrnD-rrnE)1 | 21 |

| KP1270 | W3110 (aroB zhf-5::Tn10) | 32 |

| KP1344 | W3110 (tonB::blaM) | 32 |

| KP1406 | W3110 (tonB::blaM aroB zhf-5::Tn10) | 27 |

| KP1440 | W3110 (tonB::blaM exbB::Tn10 tolQam) | 27 |

| RA1003 | W3110 (ΔexbBD::kan) | Present study |

| RA1017 | W3110 (ΔexbBD::kan ΔtolQRA) | Present study |

| RA1024 | W3110 (tonB::blaM ΔexbBD::kan ΔtolQRA) | Present study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKP325 | TonB (araBAD regulated); AraC Camr | 32 |

| pKP368 | pKP325 with T393C silent substitution in tonB | 31 |

| pKP362 | pKP325 encoding TonB ΔVal17 | 32 |

| pKP381 | pKP325 encoding His20Ala | Present study |

| pKP441 | pKP368 encoding TonB (Ala17-19) | 31 |

| pKP474 | pKP325 encoding TonB Cys18Gly, Tyr215Cys | 13 |

| pKP477 | pKP325 ΔtonB | 12 |

| pKP559 | pKP368 encoding TonB (Ala12-15, 17-19, 21-27) | Present study |

| pKP647 | pKP368 encoding TonB (Ala12-15, 17-19, 21-31) | Present study |

| pKP674 | pKP368 encoding TonB (Ala12-15, 17-19, 28-31) | Present study |

| pKP712 | pKP368 encoding TonB (Ala17-19, 21-31) | Present study |

| pKP786 | pKP647 with Tyr215Cys | Present study |

| pKP871 | pKP647 with ΔSer16 | Present study |

| pKP872 | pKP647 with Ser16Ala | Present study |

| pKP894 | pKP325 encoding Ser16Ala | Present study |

All further plasmids are derivatives of pKP325 (32), a pACYC184-based construct in which the tonB (including its transcriptional start and rho-independent terminator) and the araC genes flank a bidirectional arabinose-regulated araBAD promoter from pBAD18 (14). Plasmids encoding TonB derivatives were generated by a three-primer PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis approach as previously described (31), with primer sequences available on request. Derivatives encoding TMDs with multiple alanyl substitutions were assembled by sequential rounds of mutagenesis, with Ala codons added in blocks of 4 to 7 codons, beginning from a pKP441 template (TonBAla17-19). All TonB derivatives were confirmed by DNA sequence determination to verify that no unintended base changes were present.

Expression levels of TonB derivatives.

Cells bearing plasmids encoding individual TonB derivatives and isogenic strains encoding wild-type TonB from the native chromosomal promoter were grown with aeration at 37°C in supplemented M9 minimal salts containing 34 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol and various levels of l-arabinose. Cells were harvested at an A550 of 0.4 (as determined with a Spectronic 20 spectrophotometer with a path length of 1.5 cm) by precipitation with trichloroacetic acid (TCA), resolved on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-11% polyacrylamide gels (26), immunoblotted using TonB-specific monoclonal antibodies (30), and visualized as previously described (47). Visual comparisons of the immunoblot results identified concentrations of l-arabinose that provided levels of full-length TonB similar to that of chromosomally encoded TonB for each derivative. Following immunoblot analysis, membranes were stained for total protein with Coomassie blue and examined to confirm equivalent sample loadings in all lanes.

Colicin and bacteriophage sensitivity assays.

Colicin and phage spot titer assays were performed essentially as described previously (27), with exponential-phase cells first grown with aeration at 37°C in T broth and then suspended in 2.5 ml of molten T-top agar containing chloramphenicol at 34 μg ml− and l-arabinose as indicated and poured onto identically supplemented T plates. Serial 10-fold dilutions of a φ80 lysate in λ Ca2+ buffer or 5-fold dilutions of colicin B or colicin Ia in nonsupplemented M9 salts were applied in 5-μl aliquots to the surface of the top agar. All assays were performed in triplicate, with plates incubated for 16 h at 37°C prior to the scoring. To estimate levels of expression, cells were grown with aeration at 37°C in T broth containing l-arabinose at concentrations equivalent to those used in the plate assays, with samples evaluated by immunoblot analysis as described above.

Iron transport.

Iron transport assays were performed using aroB strains as previously described (31, 40).

Steady-state stability determinations.

Cells were grown with aeration at 37°C in supplemented M9 minimal salts containing 34 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol and various levels of l-arabinose as indicated. When cells reached an A550 of 0.4, d-fucose and d-glucose-6-phosphate were added (to 12 and 7 mM, respectively) to repress the araBAD promoter, and spectinomycin was added to 50 μg ml−1 to halt protein synthesis. Samples were harvested at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min following additions, precipitated in 10% (vol/wt) TCA, and processed as described above for immunoblot analysis. Because the half-life of TonB mRNA (∼30 s [41]) is much shorter than that of the TonB protein (at least 15 min for the TonB mutants), this assay measures degradation of the TonB protein.

In vivo chemical cross-linking.

Cells were grown with aeration at 37°C in supplemented M9 (containing 34 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol and l-arabinose as indicated) to an A550 of 0.4, harvested in 1.0-ml aliquots, centrifuged, and suspended in 938 μl of room temperature 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), to which 62 μl of fresh 16% formaldehyde monomer was added (20). Suspensions were incubated for 15 min at room temperature, centrifuged, suspended in 50 μl Laemmli sample buffer (26), incubated for 5 min at 60°C, and then resolved on SDS-11% polyacrylamide gels, with subsequent immunoblot analysis as described above.

Formation of disulfide-linked dimers.

Stationary-phase cultures were subcultured 1:100 in T broth with appropriate antibiotics at 37°C and various concentrations of l-arabinose to induce expression of TonB constructs. Cells were harvested in mid-exponential phase by precipitation with TCA and subsequent lysis in gel sample buffer containing 50 mM iodoacetamide as previously described (13). Samples were evaluated for the presence of disulfide-linked TonB dimers by immunoblot analysis of nonreducing gels.

RESULTS

TonB derivatives with TMDs bearing multiple alanyl substitutions retain activity.

We had previously shown that TonB is inactivated by either a His20Tyr or a Ser16Leu substitution in the TMD (32). The possibility that the intervening residues (Val17, Cys18, and Ile19) might also have specific roles in energization was seemingly excluded by the finding that their en masse replacement by three alanyl residues did not alter TonB function (31). To evaluate the potential contributions of other TMD residues, this strategy was extended by constructing a set of tonB derivatives that encode proteins where most or all of the putative TMD residues (except Ser16 and His20) were replaced by alanyl residues. Specifically, derivatives in which the wild-type protein sequence was maintained at only a carboxy-terminally located (residues 28 to 31), a centrally located (residues 21 to 27), or an amino-terminally located (residues 12 to 15) region of the TMD were designed. An additional, “all-Ala Ser16 His20”-encoding derivative in which all three regions were replaced by alanyl residues was constructed (Fig. 1). Plasmids carrying these derivatives or their wild-type parent under the control of an arabinose-regulated pBAD promoter were transformed into a ΔtonB enterochelin-deficient strain (KP1406), as was a vector control plasmid. The levels of TonB function in these transformants were evaluated relative to that of enterochelin-deficient, vector control-bearing cells that expressed wild-type TonB from the chromosome (KP1270) under the control of its iron-regulated native fur promoter (39).

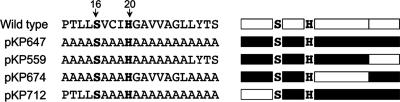

FIG. 1.

Multiply substituted TonB TMDs. The predicted amino acid sequences (residues 12 to 31) of the putative TMD of E. coli TonB and the multiply substituted derivatives used in this study are presented on the left side of the figure. Substitutions are graphically depicted on the right side of the figure, with open boxes representing the wild-type sequence and filled boxes representing alanyl substitutions. The seryl and histidyl residues at positions 16 and 20 are highlighted in the sequences and retained in the graphic depiction as reference points. Construction of each derivative is briefly described in Materials and Methods; the specific primers used and final nucleotide sequences obtained are available upon request.

Spot titer assays using serial dilutions of TonB-dependent colicins and the TonB-dependent bacteriophage φ80 provided initial measures of activity (Table 2). Each multiply substituted tonB derivative effectively complemented the ΔtonB phenotype as regards φ80 sensitivity, although the activity levels for the all-Ala Ser16 His20 derivative was one 10-fold dilution less than that achieved by the wild type and the other TonB derivatives. Similar minor distinctions were also evident with the pore-forming colicins B and Ia. For these colicins, TonB derivatives with substitutions at two of the three TMD regions showed activity levels either at or within one fivefold dilution of that seen with wild-type TonB, whereas the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TonB showed activity levels two fivefold dilutions less than that seen with wild-type TonB.

TABLE 2.

All-Ala Ser16, His20 TMD TonB supports sensitivity to Group B colicins and bacteriophage φ80

| Strain/plasmidb | Sensitivitya to:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Colicin B | Colicin Ia | Phage φ80 | |

| KP1270/pKP477 | 9 9 9 | 8 8 8 | 7 7 7 |

| KP1406/pKP477 | R R R | R R R | R R R |

| KP1406/pKP325 | 9 9 9 | 8 8 8 | 7 7 7 |

| KP1406/pKP559 | 9 9 9 | 7 7 7 | 7 7 7 |

| KP1406/pKP674 | 8 8 8 | 8 8 8 | 7 7 7 |

| KP1406/pKP712 | 8 8 8 | 7 7 7 | 7 7 7 |

| KP1406/pKP647 | 7 7 7 | 6 6 6 | 6 6 6 |

Scored as the highest dilution (5-fold for colicins, 10-fold for φ80) of agent that provided an evident zone of clearing on a cell lawn. “R” indicates tolerance (i.e., no clearing) to the undiluted colicin or phage stock. The values for three platings are presented for each strain/plasmid and agent pairing.

Strain/plasmid combinations were plated in T medium supplemented with l-arabinose as follows: for KP1406/pKP325, 0.001% (wt/vol); for KP1406/pKP559, 0.01% (wt/vol); for all other strain/plasmid combinations, 0.05% (wt/vol) l-arabinose.

The spot titer assays clearly indicated that each of the multiply substituted TonB derivatives retained significant function. These assays provide sensitive detection of TonB activity, and can distinguish gross differences in the ability of TonB to energize processes involving different TonB-gated OM transporters, but are less useful at resolving moderate differences in TonB activity. Conversely, transport assays, while insensitive to low levels of TonB activity, readily detect moderate deviations of TonB activity from wild-type levels (27).

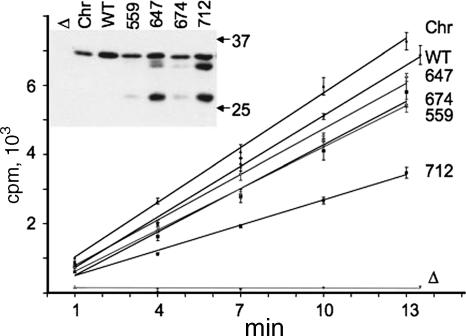

In the present study, the ability of each multiply substituted tonB derivative to support the transport of [55Fe]ferrichrome was examined (Fig. 2). Three of the TonB derivatives complemented the ΔtonB phenotype at rates similar to that achieved by wild-type TonB, whereas the TonB derivative that retained a wild-type amino-terminal region (the pKP712 derivative) was significantly less efficient, providing for transport at only one-half the rate conferred by wild-type TonB. This reduced rate of transport did not reflect lower levels of expression, as immunoblots verified that the full-length products of each of the tonB derivatives were present at levels similar to that of chromosomally encoded wild-type TonB expressed from the native promoter (Fig. 2, insert). While the amounts of full-length product present from each derivative were similar, cells expressing either the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD or the pKP712 derivative produced significant amounts of shorter, presumably degradation, products (Fig. 2, insert). Similar shorter products were also evident, but less pronounced, for the pKP559 and pKP674 TonB derivatives but not the wild type (Fig. 2 and data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Multiply substituted TonB derivatives support the transport of Fe(III) siderophores. aroB strains expressing the various TonB derivatives were grown and assayed for the uptake of [55Fe]ferrichrome as described in Materials and Methods. To verify levels of TonB expression, samples were harvested at the onset of the experiment (i.e., at 0 min) and processed for immunoblot analysis (inset). Levels of l-arabinose for individual cultures were 0.001% (wt/vol) for KP1406 bearing either pKP325 (WT) or pKP674, 0.002% (wt/vol) for KP1406 bearing pKP559, 0.005% (wt/vol) for KP1406 bearing pKP712, and 0.01% (wt/vol) for KP1406 bearing either pKP647 or pKP477 (Δ) and for KP1270 bearing pKP477 (Chr). All time points were sampled in triplicate, with data represented in counts per minute (cpm) per 108 CFU and with transport rates calculated by linear regression of the entire data set collected for each derivative for the time frame displayed. Relative transport rates for each strain/plasmid pair, expressed as numbers of cpm per 108 CFU per minute, are as follows: for KP1270/pKP477 (Chr), 528 ± 19 (r = 0.984); for KP1406/pKP477 (Δ), −2.1 ± 5 (r = 0.016); for KP1406/pKP325 (WT), 489 ± 16 (r = 0.987); for KP1406/pKP559, 400 ± 14 (r = 0.984); for KP1406/pKP647, 439 ± 14 (r = 0.987); for KP1406/pKP674, 420 ± 27 (r = 0.949); and for KP1406/pKP712, 244 ± 9 (r = 0.981).

TonB derivatives with multiply substituted TMDs were less stable than wild-type TonB.

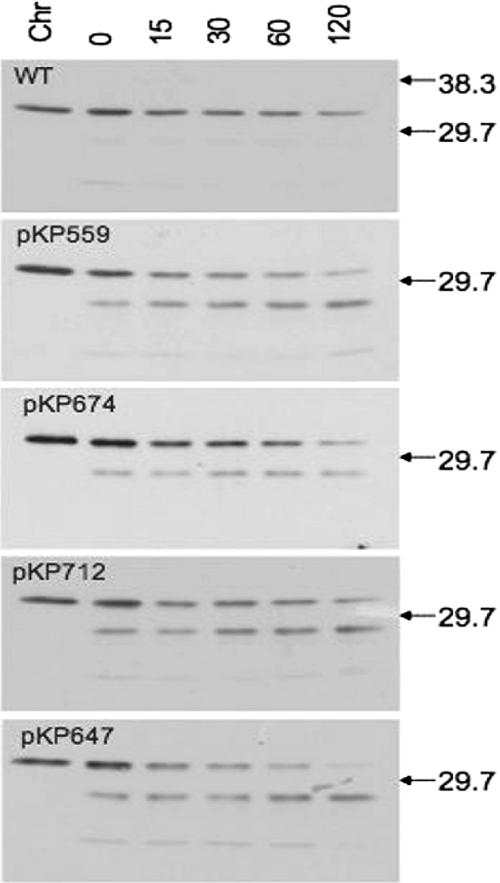

The presence of degradation products in strains assayed for iron transport suggested that some of the multiply substituted TonB derivatives were less stable than wild-type TonB. To test this possibility, we determined the steady-state chemical half-life of each derivative relative to that of wild-type TonB (Fig. 3). The apparent chemical half-life for each of the multiply substituted TonB derivatives was somewhat shorter than that of the wild type, although this distinction was pronounced only for the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD derivative (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Multiply substituted TonB derivatives have shorter steady-state half-lives than wild-type TonB. aroB strains expressing the various TonB derivatives were grown, with the chemical stabilities of individual derivatives monitored by sampling cultures for immunoblot analysis at the indicated time points (in minutes) following the cessation of protein synthesis, as described in Materials and Methods. Each data set also included a sample prepared from identically grown KP1270 and loaded in an equivalent volume to represent the level for the wild type, encoded from its native promoter (Chr). Levels of l-arabinose for individual cultures were 0.001% (wt/vol) for KP1406 bearing either pKP368 (WT), 0.0025% (wt/vol) for KP1406 bearing pKP559, 0.005% (wt/vol) for KP1406 bearing either pKP674 or pKP712, and 0.01% (wt/vol) for KP1406 bearing pKP647. The specific TonB derivative examined in each data set is identified in the upper-left corner of the panel. Lanes are labeled at the top of the first panel to indicate the KP1270 control (Chr) and the individual time points (in minutes); the positions of molecular mass standards are indicated to the right of each panel.

His20 appears to be the only essential energization motif in the TonB TMD.

In the course of multiple mutant hunts, we have recovered only three single-residue mutations that knock out TonB activity. Initial experiments identified a 3-base deletion removing a valine codon at position 17 (33). The ΔVal17 deletion lies between two residues where spontaneous point mutations were subsequently isolated, Ser16Leu and His20Tyr (32). Scanning single-residue-deletion mutagenesis suggested that Ser16 and His20 marked the boundaries of a motif essential for the efficient energization of TonB in E. coli (31). These studies also suggested that the salient features of this motif were the Ser16 and His20 residues and their position relative to one another. We subsequently realized that any mutation which deleted Ser16, Val17, Cys18, or Ile19 would have simply recreated the Ser16Leu substitution, since Leu15 moves into position 16 in each of those deletions.

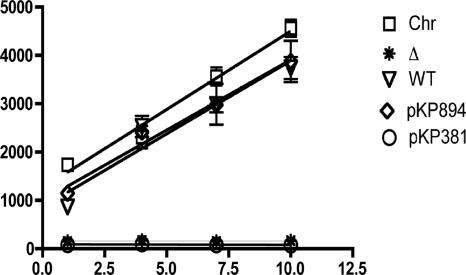

We therefore revisited the role of Ser16 by replacing it with Ala in both the wild-type scaffold and the all-Ala Ser16 His20 scaffold. The key result is that the Ser16Ala substitution was fully active in the wild-type scaffold, indicating that there was no requirement for the seryl side chain at that position (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the Ser16Ala substitution on the all-Ala scaffold (all-Ala His20) led to its inactivation (Table 3). This dichotomy strongly suggested that while none of the residues replaced in the all-Ala derivative comprises an essential motif, one or more of these residues engages in a redundant function shared with Ser16 and necessary for the efficient transduction of energy by TonB. Except for two native alanyl residues (at positions 22 and 25), the only remaining amino acid not tested directly was His20. We knew from previous experiments that Tyr was not tolerated at the His20 position. To determine whether that too was a matter of steric hindrance, we created the His20Ala substitutions on the wild-type TonB scaffold. The His20Ala substitution was inactive, thereby indicating His20 as the only functionally significant, biochemically reactive side chain on the TonB TMD (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

TonB Ser16Ala supports the transport of Fe(III) siderophores, but TonB His20Ala does not. KP1344 strains expressing TonB-Ser16Ala and TonB-His20Ala at chromosomal levels (data not shown) were grown and assayed for the uptake of [55Fe]ferrichrome as described in Materials and Methods. All time points were sampled in triplicate, with transport rates calculated by linear regression of the entire data set collected for each derivative for the time frame displayed. Relative transport rates for each strain/plasmid pair, expressed in counts per minute per 0.35 A550 ml of cells per minute, are as follows: for W3110, 324 ± 27; for KP1344/pKP477, 0.5 ± 1.3; for KP1344/pKP325, 303 ± 45; for KP1344/pKP381, 291 ± 35; and for KP1344/pKP894, −1.6 ± 1.7.

TABLE 3.

Ser16 is not essential

| Strain/plasmidb | Sensitivitya to:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Colicin B | Colicin Ia | Phage φ80 | |

| W3110/pKP477 | 8 8 8 | 7 7 7 | 8 8 7 |

| KP1344/pKP477 | R R R | R R R | R R R |

| KP1344/pKP325 | 7 7 7 | 7 6 6 | 8 8 8 |

| KP1344/pKP894 | 8 8 8 | 7 7 7 | 9 9 8 |

| KP1344/pKP871 | R R R | R R R | R R R |

| KP1344/pKP872 | R R R | R R R | 3 3 2 |

Scored as the highest dilution (5-fold for colicins, 10-fold for φ80) of agent that provided an evident zone of clearing on a cell lawn. “R” indicates tolerance (i.e., no clearing) to the undiluted colicin or phage stock. The values for three platings are presented for each strain/plasmid and agent pairing.

Strain/plasmid combinations were plated in T medium supplemented with 34 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol and 0.02% l-arabinose.

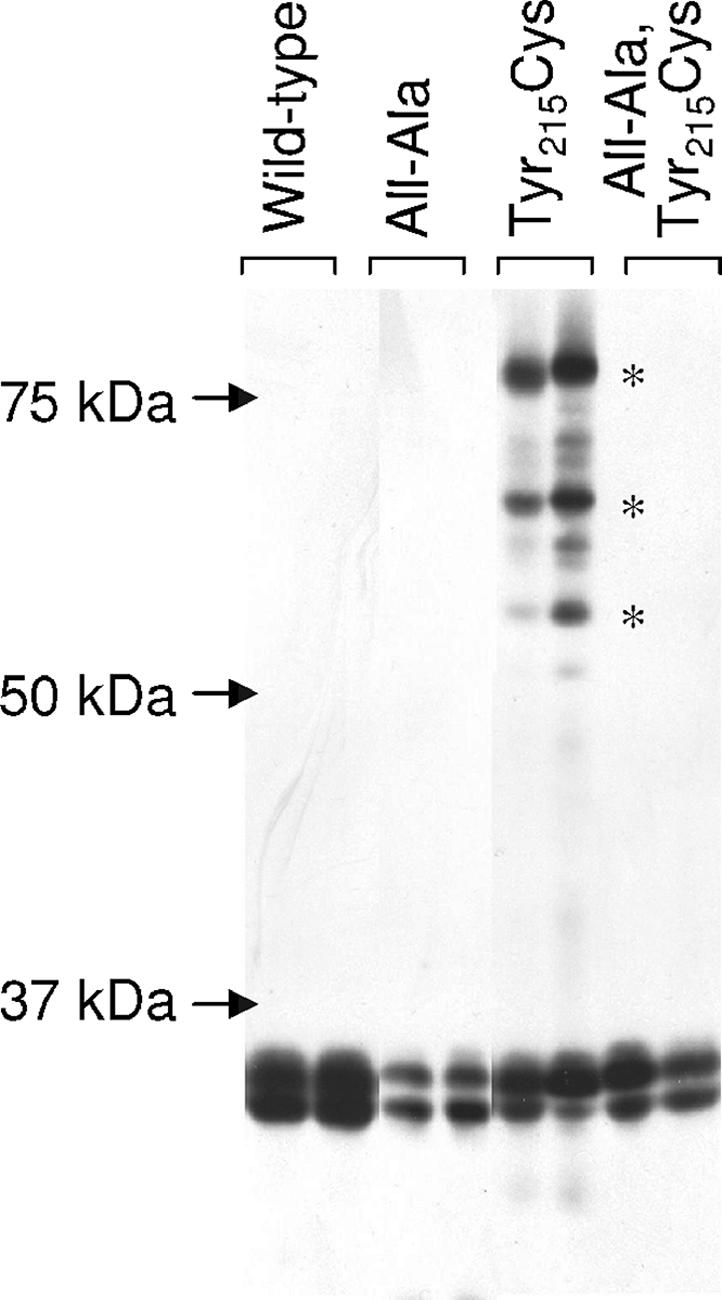

The TonB all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD prevents detectable conformational changes at the carboxy terminus.

The TonB amino-terminal TMD modulates the conformation of the TonB carboxy terminus (13). Cysteinyl substitutions at carboxy-terminal aromatic residues spontaneously form disulfide-linked dimers, but only if the TonB TMD is intact. To investigate the effects of the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD on the conformation of the TonB carboxy terminus, a TonB incorporating both the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD and the Tyr215Cys substitution was engineered. When the wild-type TonB TMD was present, the Tyr215Cys substitution formed characteristic disulfide-linked dimers on nonreducing SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 5). These dimers failed to form when the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD was present. We had previously noted that the addition of a Phe202Ala substitution to a preexisting Tyr215Cys substitution increased the efficiency of disulfide-linked dimer formation (13). To maximize the possibility of detecting disulfide-linked dimers, the combination of Tyr215Cys with Phe202Ala, the converse combination of Tyr215Ala with Phe202Cys, and high levels of induction with arabinose were tested with an all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB backbone. Although the wild-type TonB TMD supported high levels of dimers, no trace of disulfide-linked dimers was detected, even on the longest exposures, when the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD was present in the same molecule (data not shown). Two possible interpretations exist for this result: either the energy-dependent conformation of TonB does not form or it forms so rapidly that the dimers characteristic of the transition to an energized state cannot be trapped. Since, based on iron transport assays, the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB can support TonB energization, these results are most consistent with the idea that the folding of the TonB carboxy terminus has become too rapid to trap.

FIG. 5.

The all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD does not support formation of spontaneous disulfide-linked dimers. The ability of the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TonB carrying the Tyr215Cys substitution to form disulfide-linked dimers was assayed on nonreducing SDS gels with iodoacetamide in the sample lysis buffer as described previously (13). Levels of l-arabinose used for induction of TonB plasmid derivatives in strain KP1344 are as follows, from left to right on the immunoblot detected with anti-TonB monoclonal antibody: pKP325 at 0.001%, 0.005%; pKP467 at 0.1%, 0.2%; pKP474 at 0.005%, 0.01%; pKP786 at 0.01%, 0.05%. The positions of characteristic dimers are indicated by asterisks. Monomeric TonB is the doublet in each lane beneath the 37-kDa mass marker.

TonB carrying the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD makes nonspecific contact with many proteins in formaldehyde cross-linking profiles.

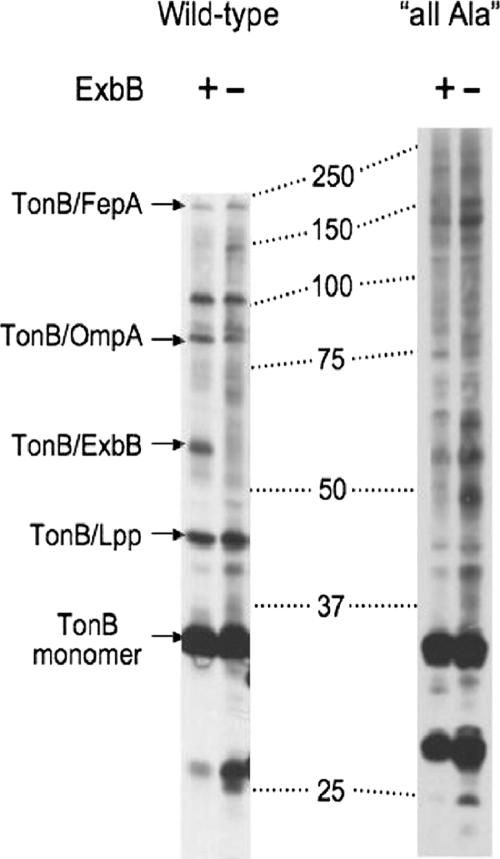

If the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD prevents regulated folding of the TonB carboxy terminus, we would expect its in vivo formaldehyde cross-linking profile to reflect that difference. Normally, wild-type TonB can form cross-linked complexes with ExbB and ExbD in the CM (detection of TonB-ExbD complex varies) and with FepA, OmpA, and Lpp in the OM (Fig. 6) (19, 28, 33, 47).

FIG. 6.

All-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB makes increased nonspecific contacts in vivo. All-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB was expressed in both the ExbB+ TolQ+ (KP1344) (+) and the ExbB− TolQ− (KP1440) (−) strains grown in T broth to assess formation of the TonB/ExbB heterodimer. Chemical cross-linking with monomeric formaldehyde and immunoblot analysis with anti-TonB monoclonal antibody were performed as described in Materials and Methods. For comparison, the known positions of TonB monomer and of the known TonB-containing complexes are indicated at the left of the panels for samples grown in M9. The positions of molecular mass standards are displayed between the two data set panels. Individual panels were selected from different gels.

Because the TonB TMD is the main region of contact between TonB and ExbB, we wanted to determine whether ExbB could cross-link to the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB. As shown in Fig. 6, the wild-type TonB-ExbB complex formed by in vivo formaldehyde cross-linking is evident in the ExbB+ strain and absent from the ExbB− TolQ− mutant. The numbers and intensities of the other cross-linked complexes were similar in both cases. In contrast, a complex between the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB and wild-type ExbB could not be detected, since the same complexes seen in the ExbB+ strain were seen in the ExbB− TolQ− mutant. Furthermore, the Ser16 His20 TMD TonB formed a number of additional, previously undetected complexes with unknown proteins, the intensities of which increased in the absence of ExbB and its paralogue TolQ (Fig. 6). Because these new, unidentified complexes might comigrate with and thus obscure an all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB/ExbB heterodimer, these data do not exclude the possibility that such a heterodimer (and the interactions that support it) might exist. Nonetheless, these data indicate that the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD increases nonspecific interactions of TonB with a variety of proteins.

The all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB requires ExbB/D.

The cross-linking results raised the formal possibility that the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB had become independent of the ExbB/D complex. To test that possibility, the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB was assayed for its ability to support energy transduction in a strain lacking ExbB/D and paralogues TolQ/R. Like the wild type, the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB was entirely dependent upon ExbB/D and TolQ/R to energize sensitivity to bacteriophage φ80. In control background KP1344 (ΔtonB), wild-type TonB expressed from pKP325 supported sensitivity to the 10th 10-fold dilution of bacteriophage φ80, the same sensitivity detected in parent strain W3110. In KP1344, the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB expressed from pKP647 supported sensitivity to the eighth 10-fold dilution of bacteriophage φ80. Strain RA1024 (ΔtonB ΔexbB ΔexbD ΔtolQ ΔtolR), expressing either plasmid-encoded wild-type TonB or the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB, remained tolerant to undiluted phage, with the exception of small turbid plaques that also appeared in KP1344 (ΔtonB) due to the presence of φ80 host range mutants typically seen when high-titer phage preparations are evaluated (16, 51). Levels of all-Ala Ser16 His20 TonB detected in RA1024 at the same level of arabinose induction as wild-type TonB were lower due to increased degradation, which was also consistent with a requirement for ExbB/D and TolQ/R (10). The more highly induced levels of all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB present during the assay in RA1024 were slightly greater than wild-type levels. Because detection of sensitivity to bacteriophage φ80 is among the most sensitive assays for low levels of TonB activity (27), these results indicated that the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB was absolutely dependent on the function provided by ExbB/D and TolQ/R.

DISCUSSION

The TonB TMD acts as the signal anchor for TonB and is also required for energy transduction (reviewed in reference 42). There is also abundant evidence for the interaction of ExbB and ExbD with the essential TonB TMD. TonB cross-links to ExbB in vivo through the TonB TMD; ExbB stabilizes TonB; mutations in the TonB TMD that inactivate TonB can be suppressed by mutations in ExbB; ExbB/D participate in TonB dimerization that occurs through its TMD (10, 22, 31, 32, 33, 46, 48).

We previously defined Ser16 His20 and the register of three residues between them as an essential feature of the TonB TMD based on a deletion scanning analysis (31). To increase our understanding of the role of the TonB TMD in energy transduction, in this report we sequentially replaced blocks of the TMD with alanyl residues, until all residues except Ser16 and His20 had been thus replaced (all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB).

Two residues (Leu27 and Ser31) on the same face of the putative α-helix as Ser16 and His20 are shared with the TonB paralog TolA (25). Despite this conservation, replacement of either or both residues with alanine did not greatly affect TonB activity. This is consistent with the failure of our previous mutant hunts to identify mutations at either Leu27 or Ser31 and with the near-wild-type phenotype reported for the substitution at Ser31 characterized by Traub et al. (50). Similar mutations in TolA also had no phenotype (11). While it was not surprising that Leu27 and Ser31 were dispensable, the fact that we could replace the entire TMD except for Ser16 and His20 with alanyl residues and retain 90% of TonB activity was unexpected. Just as with wild-type TonB, the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB was dependent on ExbB/D for its activity.

Since nearly the entire TonB TMD could be replaced by alanyl residues with minimal detriment, we expanded the mutagenesis to include Ser16 and His20. We had previously isolated a spontaneous Ser16Leu mutation that inactivated TonB and had demonstrated that Ser16 could not be deleted without inactivating TonB (31, 32). In direct contrast to these earlier results, we show here that Ser16 was not essential, since Ser16Ala in a wild-type TonB TMD had no effect on TonB activity. The contradiction with our earlier analyses of Ser16Leu can be explained if Ser16Leu somehow sterically hinders correct assembly of TonB in the ExbB/D complex, consistent with the observed inability of Ser16Leu-TonB to detectably cross-link to ExbB (32). Thus, the only salient feature of the Ser16 residue was the small size of its side chain. Ironically, in our previous studies, the deletion of any one of the three residues between Ser16 and His 20, as well as Ser16 itself, moved Leu15 into position 16 and recreated the original Ser16Leu putative assembly mutant. Consistent with earlier observations of TonB His20Tyr, TonB His20Arg, and mutations in the TolA TMD (11, 32, 50), the His20Ala substitution expressed at chromosomal levels was inactive in a wild-type TonB TMD seaffold. Thus, the only essential biochemically reactive side chain for TonB energy transduction is that of His20.

ExbB/D and the TonB TMD regulate dimerization of the TonB carboxy terminus (13, 46). Molecules bearing Cys substitutions at any of four aromatic residues in the TonB carboxy terminus can spontaneously form disulfide-linked dimers in the CM. Inactive mutations in the TonB TMD or the absence of ExbB/D prevents the formation of disulfide-linked dimers (13). TonB also dimerizes through its amino-terminal TMD in an ExbB/D-supported manner (46). The behavior of the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB in two more-mechanistically informative assays yielded unexpected results.

In the first assay, the unexpected effect of the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB was to eliminate disulfide-linked dimer formation at the TonB carboxy terminus. One possible interpretation is that the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD does not dimerize, which could prevent dimerization at the TonB carboxy terminus. Although it has not been demonstrated directly, it is reasonable to propose that TonB dimerization through the TMD is required for TonB function, since it does not occur efficiently in the absence of ExbB/D (46). Because the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB is 90% active and ExbB/D dependent when expressed at chromosomal levels, it almost certainly can dimerize through the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD.

Because the TonB TMD plays an important role in regulating dimerization at the carboxy terminus (13, 46), a second interpretation is that the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD may have lost most of the interfacial amino acid side chains that allow efficient regulation of carboxy terminus dimerization that is mediated through its TMD and ExbB/D. If regulation of TonB carboxy-terminal conformations by ExbB/D were normally required to enhance TonB activity, the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB would predictably be much less active. In contrast, we see that the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB is 90% as active as wild-type TonB, suggesting that the normal role of ExbB/D may be to slow down conformational changes at the carboxy terminus. We favor this interpretation. By this argument, the rate at which the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB signals transitions at the carboxy terminus might be sufficiently rapid that dwelling time in the trappable conformation would be very short.

The second assay that gave unexpected results was in vivo formaldehyde cross-linking. We previously used formaldehyde cross-linking in vivo to characterize a set of TonB-dependent complexes with the OM proteins FepA, OmpA, and Lpp and with the CM proteins ExbB and ExbD (20, 32, 33, 47). Formaldehyde cross-linked complexes with OM proteins are formed by inactive TonB (13), while formaldehyde cross-links between TonB and ExbB appear to represent interactions of active TonB (33). TonB-ExbB cross-linking occurs through the TonB TMD such that the appearance and disappearance of TonB-ExbB complexes correlate with TonB activity (33).

In this study, the in vivo formaldehyde cross-linking profiles for the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD derivative appeared to be lacking all of the characteristic complexes made by wild-type TonB and in their place a significantly larger number of complexes with unknown partner proteins appeared (19, 20, 47). Nonetheless, they represent close contacts through methylene bridges made by TonB with unknown proteins. Unlike the case for wild-type TonB, the absence of ExbB/D and TolQ/R with the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB resulted not in the loss of any particular complex but in the intensification of all nonspecific cross-linked complexes. This would be consistent with the idea that, while ExbB/D were not able to regulate the TonB carboxy terminus through the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB as effectively as a wild-type TonB TMD, the total absence of ExbB/D left the TonB carboxy terminus completely unregulated by the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD and thus increased the opportunity for nonspecific contacts. The absence of a characteristic all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB-ExbB complex was probably due to reorientation of formaldehyde cross-linkable residues such that they no longer can cross-link. It was, however, clear that the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB retained contact with ExbB/D because ExbB/D were still required for all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB activity.

The capacity of the TonB carboxy terminus to bind indiscriminately to diverse proteins or polypeptides in unusual circumstances is supported by previous observations. (i) Double alanyl substitutions at aromatic amino acids in the TonB carboxy terminus render it inactive and yet result in a formaldehyde cross-linking profile that shows, if anything, more numerous nonspecific contacts than those observed in Fig. 6. These data were reported in reference 13 but not shown at that time because we did not know how to interpret them. (ii) In a strain lacking all OM siderophore transporters, ∼60% of TonB is found associated with the OM. This suggests that if cognate binding partners are not present, not only will alternatives be found, they will be found in abundance (19). (iii) Nonenergized TonB cross-links in vivo to OmpA and Lpp, but mutations in these proteins have no effect on TonB activity (13, 19, 22). (iv) Phage panning with the purified TonB carboxy-terminal domain identifies unexpected transporter contacts whose biological relevance has yet to be established (4; for a review, see reference 43). Taken together, these results suggest that the carboxy terminus of TonB can, under various circumstances, bind a variety of peptides efficiently and nonspecifically.

The in vivo formaldehyde cross-linking studies with all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB revealed indiscriminate cross-linking to a large number of proteins, while studies of disulfide-linked dimers at the TonB carboxy terminus suggested the possibility that conformational changes mediated through the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD were proceeding too rapidly to trap. Taken together, these data suggest that one potential function of the ExbB/D complex would be to act as a governor, down-regulating the rate of TonB carboxy terminus folding to allow time for binding to correct protein targets, ligand-bound OM transporters. Without the ability to efficiently down-regulate conformational changes at its carboxy terminus, the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD TonB might contact many proteins indiscriminately, including OM transporters, while maintaining the ability to transduce energy (perhaps at greater energetic cost to the cell). In a model for TonB recognition of ligand-bound transporters, TonB would be assembled into the ExbB/D complex, where ExbD (which, like TonB, primarily occurs within the periplasmic space) chaperones TonB into a semidisordered state that is able to both span the periplasmic space and specifically identify a ligand-bound OM transporter.

The concept of an ExbB/D down-regulated conformation at the TonB carboxy terminus would help resolve a major contradiction that exists between the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)/crystal structures of TonB obtained thus far and in vivo studies on TonB.

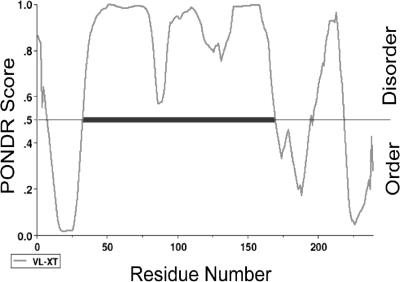

In vivo, the phenotypes of single TonB-Ala substitutions at carboxy-terminal aromatic residues suggest they are involved in differential and specific recognition of OM transporters, colicins, and possibly phages (12). If so, they are exposed on the surface of TonB. Consistent with that idea, TonB-Cys substitutions at the aromatic residues spontaneously form disulfide-linked dimers, again suggesting that the aromatic side chains are surface exposed in CM TonB (13). In contrast, the aromatic side chains are buried in TonB crystal/NMR structures of the carboxy-terminal domain, which represent TonB lacking its amino terminus and any influence of ExbB/D or the CM pmf (5, 24, 37, 38, 46a). TonB conformational changes at the carboxy terminus are regulated through the TonB TMD and ExbB/D (13, 46). It seems reasonable to suggest that when the carboxy-terminal conformation of TonB is not appropriately regulated, it binds nonspecifically to incorrect targets. When the TonB TMD is altogether absent, it forms the structures seen by NMR and crystallography. Consistent with the NMR structure of TonB residues 103 to 151 (38), a large central segment of TonB is predicted to be structurally disordered (Fig. 7). Perhaps the regulated TonB carboxy-terminal conformations involve order-disorder transitions.

FIG. 7.

TonB is predicted to have significant disorder. The TonB amino acid sequence from E. coli (SwissProt accession no. P02929) was analyzed for potential regions of disorder using PONDR. Amino acid sequences are scanned from the amino to the carboxy terminus for regions of disorder (abscissa), indicated by curves above the ordinate midline. Significant regions of disorder are indicated by a horizontal black bar at the midline.

There are two basic models for TonB energy transduction: mechanical pulling and twisting and shuttling (5, 6, 29, 34, 43, 52). Much of the data regarding TonB, ExbB, and ExbD are consistent with either model. It is important to know which model is correct because a shuttle model requires the ability to store energy as conformational change or chemical modification, whereas a mechanical model does not. The model for regulation of TonB disorder-order transitions serves equally well whether TonB shuttles or pulls mechanically because it describes how the TonB carboxy terminus might be able to span the periplasmic space and identify ligand-bound transporters with specificity and low affinity (8). If, on the one hand, TonB shuttles, it may be that His20 is part of a phosphorylation cascade. On the other hand, if TonB works through transduction of mechanical energy, it may be that His20 is the primary handle in the TMD.

Regardless of which model is correct, one may ask what the role of Ser16 is. Ser16Ala is active in a wild-type TonB TMD, indicating that it normally plays no role. Yet, it seems to be the proverbial straw that breaks the camel's back when placed into the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TonB TMD context and expressed at chromosomal levels. Replacement of Ser16 with Ala or deletion of Ser16 resulted in the nearly complete inactivation of the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TonB. One explanation is that a landmark side chain is important for His20 to be positioned properly in the ExbB/D complex for maximal interface between the TMDs. Loss of all landmarks was clearly not functional. Alternatively, export of the all-Ala His20 to the CM may be impaired in some way. That possibility seems unlikely, however, since the overall hydrophobicity and hence signal sequence-like character of the TonB TMD is similar in the all-Ala Ser16 His20 TMD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an award to R.L. from the National Science Foundation (MCB0315983) and an award to K.P. from the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences (GM42146).

We thank Lisa Gloss and Jane Dyson for helpful discussions. Access to PONDR was kindly provided by Molecular Kinetics (Indianapolis, IN).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bassford, P. J., C. Bradbeer, R. J. Kadner, and C. A. Schnaitman. 1976. Transport of vitamin B12 in tonB mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 128:242-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradbeer, C., and M. L. Woodrow. 1976. Transport of vitamin B12 in Escherichia coli: energy dependence. J. Bacteriol. 128:99-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun, V., S. Gaisser, C. Herrrmann, K. Kampfenkel, H. Killman, and I. Traub. 1996. Energy-coupled transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli: ExbB binds ExbD and TonB in vitro, and leucine 132 in the periplasmic region and aspartate 25 in the transmembrane region are important for ExbD activity. J. Bacteriol. 178:2326-2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter, D. M., J.-N. Gagnon, M. Damlaj, S. Mandava, L. Makowski, D. J. Rodi, P. D. Pawelek, and J. W. Coulton. 2006. Phage display reveals multiple contact sites between FhuA, an outer membrane receptor of Escherichia coli, and TonB. J. Mol. Biol. 357:236-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, C., A. Mooser, A. Plückthun, and A. Wlodawer. 2001. Crystal structure of the dimeric C-terminal domain of TonB reveals a novel fold. J. Biol. Chem. 276:27535-27540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chimento, D. P., R. J. Kadner, and M. C. Wiener. 2005. Comparative structural analysis of TonB-dependent outer membrane transporters: implications for the transport cycle. Proteins 59:240-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyson, H. J., and P. E. Wright. 2005. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6:197-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernst, F. D., J. Stoof, W. M. Horrevoets, E. J. Kuipers, J. G. Kustars, and A. H. van Vliet. 2006. NikR mediates nickel-responsive transcriptional repression of the Helicobacter pylori outer membrane proteins FecA3 (HP1400) and FrpB4 (HP1512). Infect. Immun. 74:6821-6828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer, E., K. Günter, and V. Braun. 1989. Involvement of ExbB and TonB in transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli: phenotypic complementation of exb mutants by overexpressed tonB and physical stabilization of TonB by ExbB. J. Bacteriol. 171:5127-5134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Germon, P., T. Clavel, A. Vianney, R. Portalier, and J.-C. Lazzaroni. 1998. Mutational analysis of the Escherichia coli K-12 TolA N-terminal region and characterization of its TolQ-interacting domain by genetic suppression. J. Bacteriol. 180:6433-6439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh, J., and K. Postle. 2004. Evidence for dynamic clustering of carboxy-terminal aromatic amino acids in TonB-dependent energy transduction. Mol. Microbiol. 51:203-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh, J., and K. Postle. 2005. Disulphide trapping of an in vivo energy-dependent conformation of Escherichia coli TonB protein. Mol. Microbiol. 55:276-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guzman, L.-M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hannavy, K., G. C. Barr, C. J. Dorman, J. Adamson, L. R. Mazengera, M. P. Gallagher, J. S. Evans, B. A. Levine, I. P. Trayer, and C. F. Higgins. 1990. TonB protein of Salmonella typhimurium: a model for signal transduction between membranes. J. Mol. Biol. 216:897-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hantke, K., and V. Braun. 1978. Functional interaction of the tonA/tonB receptor system in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 135:190-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Held, K. G., and K. Postle. 2002. ExbB and ExbD do not function independently in TonB-dependent energy transduction. J. Bacteriol. 171:5170-5173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgs, P. I., R. A. Larsen, and K. Postle. 2002. Quantification of known components of the Escherichia coli TonB energy transduction system: TonB, ExbB, ExbD and FepA. Mol. Microbiol. 44:271-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgs, P. I., T. E. Letain, K. K. Merriam, N. S. Burke, H. Park, C. Kang, and K. Postle. 2002. TonB interacts with nonreceptor proteins in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:1640-1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgs, P. I., P. S. Myers, and K. Postle. 1998. Interactions in the TonB-dependent energy transduction complex: ExbB and ExbD form homomultimers. J. Bacteriol. 180:6031-6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill, C. W., and B. W. Harnish. 1981. Inversions between ribosomal RNA genes of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:7069-7072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaskula, J. C., T. E. Letain, S. K. Roof, J. T. Skare, and K. Postle. 1994. Role of the TonB amino terminus in energy transduction between membranes. J. Bacteriol. 176:2326-2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karlsson, M., K. Hannavy, and C. F. Higgins. 1993. A sequence-specific function for the amino-terminal signal-like sequence of the TonB protein. Mol. Microbiol. 8:379-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ködding, J., F. Killig, P. Polzer, S. P. Howard, K. Diederichs, and W. Welte. 2005. Crystal structure of a 92-residue C-terminal fragment of TonB from Escherichia coli reveals significant conformational changes compared to structures of smaller TonB fragments. J. Biol. Chem. 280:3022-3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koebnik, R. 1993. Microcorrespondence: the molecular interaction between components of the TonB-ExbBD-dependent and of the TolQRA-dependent bacterial uptake systems. Mol. Microbiol. 9:219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsen, R. A., G. J. Chen, and K. Postle. 2003. Performance of standard phenotypic assays for TonB activity, as evaluated by varying the level of functional, wild-type TonB. J. Bacteriol. 185:4699-4706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsen, R. A., D. Foster-Hartnett, M. A. McIntosh, and K. Postle. 1997. Regions of Escherichia coli TonB and FepA proteins essential for in vivo physical interactions. J. Bacteriol. 179:3213-3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larsen, R. A., T. E. Letain, and K. Postle. 2003. In vivo evidence of TonB shuttling between the cytoplasmic and outer membrane in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 49:211-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsen, R. A., P. S. Myers, J. T. Skare, C. L. Seachord, R. P. Darveau, and K. Postle. 1996. Identification of TonB homologs in the family Enterobacteriaceae and evidence for conservation of TonB-dependent energy transduction complexes. J. Bacteriol. 178:1363-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larsen, R. A., and K. Postle. 2001. Conserved residues Ser(16) and His(20) and their relative positioning are essential for TonB activity, cross-linking of TonB with ExbB, and the ability of TonB to respond to proton motive force. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8111-8117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larsen, R. A., M. G. Thomas, and K. Postle. 1999. Protonmotive force, ExbB and ligand-bound FepA drive conformational changes in TonB. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1809-1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larsen, R. A., M. G. Thomas, G. E. Wood, and K. Postle. 1994. Partial suppression of an Escherichia coli TonB transmembrane domain mutation (ΔV17) by a missense mutation in ExbB. Mol. Microbiol. 13:627-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Letain, T. E., and K. Postle. 1997. TonB protein appears to transduce energy by shuttling between the cytoplasmic membrane and the outer membrane in Gram-negative bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 24:271-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 36.Neugebauer, H., C. Herrmann, W. Kammer, G. Schwarz, A. Nordheim, and V. Braun. 2005. ExbBD-dependent transport of maltodextrins through the novel MalA protein across the outer membrane of Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 187:8300-8311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pawelek, P. D., N. Croteau, C. Ng-Thow-Hing, C. M. Khursigara, N. Moiseeva, M. Allaire, and J. Coulton. 2006. Structure of TonB in complex with FhuA, E. coli outer membrane receptor. Science 312:1399-1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peacock, R. S., A. M. Weljie, S. P. Howard, F. D. Price, and H. J. Vogel. 2005. The solution structure of the C-terminal domain of TonB and interaction studies with TonB box peptides. J. Mol. Biol. 345:1185-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Postle, K. 1990. Aerobic regulation of the Escherichia coli tonB gene by changes in iron availability and the fur locus. J. Bacteriol. 172:2287-2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Postle, K. TonB system, in vivo assays and characterization. Methods Enzymol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Postle, K., and R. Good. 1985. A bidirectional Rho-independent transcriptional terminator between the E. coli tonB gene and an opposing gene. Cell 41:577-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Postle, K., and R. J. Kadner. 2003. Touch and go: tying TonB to transport. Mol. Microbiol. 49:869-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Postle, K., and R. A. Larsen. TonB dependent energy transduction between outer and cytoplasmic membranes. Biometals, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Postle, K., and J. T. Skare. 1988. Escherichia coli TonB protein is exported from the cytoplasm without proteolytic cleavage of its amino terminus. J. Biol. Chem. 263:11000-11007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roof, S. K., J. D. Allard, K. P. Bertrand, and K. Postle. 1991. Analysis of Escherichia coli TonB membrane topology by use of PhoA fusions. J. Bacteriol. 173:5554-5557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sauter, A., S. P. Howard, and V. Braun. 2003. In vivo evidence for TonB dimerization. J. Bacteriol. 185:5747-5754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46a.Shultis, D. D., M. D. Purdy, C. N. Banchs, and M. C. Wiener. 2006. Outer membrane active transport: structure of the BtuB:TonB complex. Science 312:1396-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skare, J. T., B. M. M. Ahmer, C. L. Seachord, R. P. Darveau, and K. Postle. 1993. Energy transduction between membranes. TonB, a cytoplasmic membrane protein, can be chemically cross-linked in vivo to the outer membrane receptor FepA. J. Biol. Chem. 268:16302-16308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skare, J. T., and K. Postle. 1991. Evidence for a TonB-dependent energy transduction complex in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5:11000-11007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skare, J. T., S. K. Roof, and K. Postle. 1989. A mutation in the amino terminus of a hybrid TrpC-TonB protein relieves over-production lethality and results in cytoplasmic accumulation. J. Bacteriol. 171:4442-4447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Traub, I., S. Gaisser, and V. Braun. 1993. Activity domains of the TonB protein. Mol. Microbiol. 8:409-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wayne, R., and J. B. Neilands. 1975. Evidence for common binding sites for ferrichrome compounds and bacteriophage φ80 in the cell envelope of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 121:497-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weiner, M. C. 2005. TonB-dependent outer membrane transport: going for Baroque? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15:394-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]