Abstract

The observed lengthening of the C period in the presence of a defective ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase has been assumed to be due solely to the low deoxyribonucleotide supply in the nrdA101 mutant strain. We show here that the nrdA101 mutation induces DNA double-strand breaks at the permissive temperature in a recB-deficient background, suggesting an increase in the number of stalled replication forks that could account for the slowing of replication fork progression observed in the nrdA101 strain in a Rec+ context. These DNA double-strand breaks require the presence of the Holliday junction resolvase RuvABC, indicating that they have been generated from stalled replication forks that were processed by the specific reaction named “replication fork reversal.” Viability results supported the occurrence of this process, as specific lethality was observed in the nrdA101 recB double mutant and was suppressed by the additional inactivation of ruvABC. None of these effects seem to be due to the limitation of the deoxyribonucleotide supply in the nrdA101 strain even at the permissive temperature, as we found the same level of DNA double-strand breaks in the nrdA+ strain growing under limited (2-μg/ml) or under optimal (5-μg/ml) thymidine concentrations. We propose that the presence of an altered NDP reductase, as a component of the replication machinery, impairs the progression of the replication fork, contributing to the lengthening of the C period in the nrdA101 mutant at the permissive temperature.

Ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase (NDP reductase) is the only specific enzyme required for the enzymatic formation of deoxyribonucleotides (dNTPs), the precursors of DNA synthesis in Escherichia coli. NDP reductase is a 1:1 complex of two nonidentical subunits called proteins R1 and R2, encoded by genes nrdA and nrdB, respectively (for a review, see reference 3). The best-known defective NDP reductase mutant of E. coli contains a thermolabile R1 subunit encoded by the nrdA101 allele. The activity of the enzyme measured in crude extracts of nrdA101 strains is limited to 6% of the wild-type activity at 25°C (6), and the dNTP pool is lower than wild type even at permissive temperatures (16). Our laboratory has shown that the presence of the nrdA101 allele lowers the replication rate of the mutant strain at the permissive temperature, as a nrdA101 mutant replicates the chromosome in 154 min at 30°C, while a nrdA+ strain does so in 98 min (10). Regarding the detrimental effect of the nrdA101 allele on the activity of the enzyme, this DNA replication effect is assumed to be due to the decrease in the NDP reductase activity as a dNTP provider. However, NDP reductase has been proposed as a component of the replication hyperstructure (10), and consequently the structure of the NDP reductase encoded by the nrdA101 allele might provoke a structural alteration of the replication hyperstructure that could also contribute to the lengthening of the C period in the mutant. A possible consequence of an altered replication hyperstructure might be a frequent replication fork arrest. The goal of this work was to investigate the occurrence of replication fork arrest in the presence of NDP reductase encoded by the nrdA101 allele. To distinguish between the structural and functional contributions of NDP reductase to the replication fork arrest, we mimicked the limitation of NDP reductase activity as a dNTP provider by using thymine limitation in an nrdA+ strain. Thymine limitation in the nrdA+ background would be used to decrease the rate of DNA replication without affecting either the NDP reductase structure or the major metabolic pathways in the cell (26, 32, 33).

Arrested replication forks in E. coli are known to experience breakage or to be susceptible to it (2, 15, 25), although DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) have not always been found after replication fork arrest (1, 8). DSBs can have various origins, including exogenous factors such as DNA damage by radiation or chemical agents. However, if they resulted from stalled forks, they would have been generated (i) by direct endonucleolytic cleavage of the stalled fork (2, 11, 12, 15, 25) or (ii) by endonucleolytic cleavage of the stalled fork after regression by the specific reaction named “replication fork reversal” (RFR), as has been extensively studied by Michel and coworkers (21). In the latter case, newly synthesized strands anneal, forming a four-way junction (Holliday junction [HJ]). With inactivation of RecBCD, the HJs at the replication forks accumulate and are resolved by the RuvABC complex, resulting in broken replication forks (Fig. 1D) (29). Consequently, the occurrence of DSBs dependent on RuvABC activity in a recB-deficient strain would indicate that these DSBs were generated after the processing of an HJ created by RFR at stalled forks. If this occurs, we can infer that in a rec+-proficient background the stalled replication forks would proceed after being regressed by following the recombinational pathway (Fig. 1B) or by the action of RecBCD exonuclease to degrade the DNA tail (Fig. 1 C). Using this experimental approach, we investigated the induction of DSBs in the nrdA101 recB mutant strain at the permissive temperature to determine whether the presence of an altered NDP reductase increases the incidence of stalled replication fork. In this work we show that an altered NDP reductase increases stalled forks and induces RFR. None of theses effects were observed by limiting the TTP supply in an nrdA+ strain.

FIG. 1.

The replication fork reversal model (adapted from reference 21 with permission of the publisher). In the first step (A), the replication fork is arrested, causing fork reversal. The reversed fork forms an HJ (two alternative representations of this structure are shown, indicated by the open X and parallel stacked X). In Rec+ cells (B), RecBCD initiates RecA-dependent homologous recombination, and the resulting double HJ is resolved by RuvABC. Alternatively, if RecBCD encounters the HJ in the absence of RecA (C), the DNA double-strand end is degraded up to the HJ, restoring a fork structure. In both cases, replication restarts by a PriA-dependent process. In the absence of RecBCD (D), resolution of the HJ by RuvABC leads to DSBs at the stalled replication fork. Continuous line, parental chromosome; dashed lines, newly synthesized strands; disk, RuvAB; incised disk, RecBCD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

E. coli JS1018 (nrdA101 thyA arg his thi malA rpsL su xyl mtl) is a Pol+ Thy− low-requirement derivative of strain E1011 obtained from R. McMacken (Stanford University, Stanford, CA). All the strains used in this work were JS1018 derivatives (Table 1). Strains were constructed by the standard P1 transduction method with selection for the appropriate resistance (22). Given that the priA null mutant may accumulate suppressor mutations, the nrdA101 priA2 double mutant was constructed in the presence of the pAM-priA+ plasmid, which carries the wild-type priA gene and an IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-dependent replication origin. This plasmid allows cell growth in a priA+ context if IPTG is present and allows priA+ gene curing in the absence of IPTG (8).

TABLE 1.

Strains used

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Construction or source |

|---|---|---|

| JS1018 | nrdA101 thyA arg his thi malA Lr rpsL mtl xyl | This lab |

| JS627 | JS1018 Δ(recA-srl)::Tn10 | P1 transduction of Δ(recA-srl)::Tn10 in JS1018 |

| JS628 | JS1018 recB258::Tn10 | P1 transduction of recB258::Tn10 in JS1018 |

| JS704 | JS1018 ΔruvABC::Cm | P1 transduction of ΔruvABC::Cm in JS1018 |

| JS705 | JS1018 ΔruvABC::Cm recB258::Tn10 | P1 transduction of recB258::Tn10 in JS704 |

| JS816 | JS1018 Δ(recA-srl)::Tn10 ΔruvABC::Cm | P1 transduction of Δ(recA-srl)::Tn10 in JS704 |

| JS891 | JS1018 priA2::Kam/pAM-priA | P1 transduction of priA2::Kam in JS1018/pAM-priA |

| JK607 | JS1018 nrdA+ yfaL::Tn5 | P1 transduction of nrdA+yfaL::Tn5 in JS1018 |

| JK625 | JK607 Δ(recA-srl)::Tn10 | P1 transduction of Δ(recA-srl)::Tn10 in JK607 |

| JK626 | JK607 recB258::Tn10 | P1 transduction of recB258::Tn10 in JK607 |

| JK706 | JK607 ΔruvABC::Cm | P1 transduction of ΔruvABC::Cm in JK607 |

| JK707 | JK607 ΔruvABC::Cm recB258::Tn10 | P1 transduction of recB258::Tn10 in JK706 |

| JJC275 | Δ(recA-srl)::Tn10/mini F recA Ampr | B. Michel |

| JJC777 | recB258:: Tn10/pDWS2 (pBR322 recBCD+) | B. Michel |

| JJC754 | ΔruvABC::Cm | B. Michel |

| JJC1398 | priA2::Kam sfiA11/pAM priA+ | B. Michel |

Bacteria were grown by shaking at 30°C in M9 minimal medium containing M9 salts, 2 μg/ml thiamine, 0.4% glucose, 20 μg/ml of required amino acids, 5 μg/ml thymidine, and 0.2% Casamino Acids. Growth was monitored by optical density (OD) at 450 nm.

Determination of the C period.

DNA synthesis was determined by growing the cells in M9 minimal medium containing 1 μCi/ml of [methyl-3H]thymidine (20 Ci/mmol) (ICN) and assaying the radioactive acid-insoluble material. The number of replication rounds, n (26, 31), was determined by runout replication experiments after adding 150 μg/ml rifampin to a mid-log-phase growing culture (23), and it was obtained from the amount of runout DNA synthesis (ΔG) by the algorithm ΔG = [2nnln2/(2n − 1)] − 1 (31). The C period value in the steady-state culture was determined as C = nτ (26). τ is defined as the doubling time in minutes measured by OD.

Measurement of DSBs by PFGE.

Measurements of DSBs were performed as described in the literature (20, 29). Briefly, for chromosome labeling, cells were grown in minimal medium with 0.2% Casamino Acids in the presence of 5 μCi/ml of [methyl-3H]thymidine (20 Ci/mmol) (ICN) until the culture reached an OD of 0.1. Cells were collected, washed, and embedded in agarose plugs. Gentle lysis was performed in the plugs before using them for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). The proportion of migrating DNA was determined by cutting each lane into slices and counting the tritium present in the wells and in the gel slices. The linear DNA values were expressed as the ratio (percent) between cpm in the gel slices and cpm in the gel slices plus well.

Test of colony viability.

CFU experiments were performed as described in the literature (5). Briefly, entire colonies were cut out as agarose plugs from rich medium plates after 48 h of incubation at 30°C, inoculated in 1 ml of M9 salts buffer, and shaken for 1 h at 30°C for full suspension of the colony. Appropriate dilutions of these suspensions were plated onto rich or minimal medium plates containing 2 μg/ml or 5 μg/ml of thymidine to count CFU at 30°C or 37°C. To prevent the accumulation of cells carrying suppressor mutations, a priA::Kam mutant was constructed in the presence of the plasmid pAM-priA+, which carries the wild-type priA gene and a conditional replication origin (8). When the CFU of the nrdA101 priA2::Kam/ pAM-priA+ strain were determined, colonies of this strain were obtained by plating first in the presence of IPTG (500 μM) plus spectinomycin 25 (μg/ml) and then following the same protocol as described above; i.e., individual colonies from the selection plates were plated in rich medium with neither IPTG nor spectinomycin in order to lose the pAM-priA+ plasmid and determine the effect of the priA2::Kam mutation. After 48 h of incubation at 30°C, entire colonies were cut out as agarose plugs, inoculated in 1 ml of M9 salts buffer, and shaken for 1 h at 30°C for full suspension of the colony. Appropriate dilutions of these suspensions were plated onto rich medium and incubated at 30°C or 37°C to count CFU.

Flow cytometry.

DNA content per cell was measured by flow cytometry using a Bryte HS (Bio-Rad) flow cytometer essentially as previously described (7, 30). When the OD at 450 nm of each culture growing at 30°C or 37°C in M9 minimal medium reached 0.2, a portion of the cultures was transferred into another flask, and rifampin (150 μg/ml) and cephalexin (50 μg/ml) were added to inhibit new rounds of chromosomal replication and cell division, respectively. These treated cultures were grown for an additional 4 h with continuous shaking, after which 400 μl of each culture was added to 7 ml of 74% ethanol. Approximately 1.5 ml of each fixed sample was centrifuged, and the pellets were washed in 1 ml of ice-cold staining buffer (10 mM Tris, 10 mM MgCl2 [pH 7.4] in sterile distilled water) and resuspended in 65 μl of staining buffer and 65 μl of staining solution (40 μg/ml ethidium bromide and 200 μM mithramycin A). The cells were incubated on ice in the dark for at least 30 min and run in the Bryte-HS (Bio-Rad) flow cytometer at 390 to 440 nm.

RESULTS

nrdA101 recB strains contain a high level of DSBs.

Arrest of replication forks is known to cause DSBs (2, 15). In order to study whether there was an increase in the number of stalled replication forks caused by the presence of an altered NDP reductase, we determined the amount of DSBs according to the method developed by Michel et al. (20) by using PFGE combined with cell lysis in agarose plugs. To determine the amount of broken DNA produced, it is necessary to prevent degradation of linear DNA and repair of DSBs. This can be achieved by inactivating RecBCD activity using a recB-deficient background, although recA- recD-deficient strains could also be used (20).

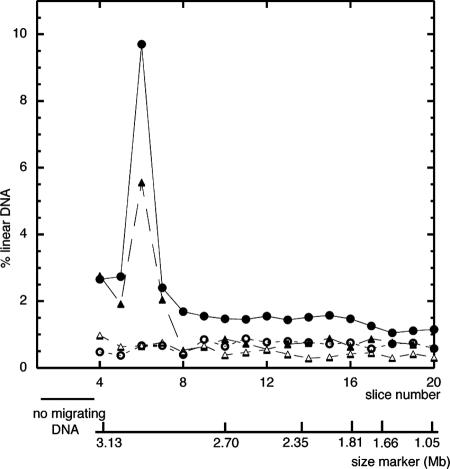

In the present work the levels of DSBs in nrdA101 recB and nrdA+ recB strains growing at 30°C were quantified by the amount of linear DNA as measured by PFGE (Table 2). Typical profiles of gel migration for the different strains are shown in Fig. 2. The results indicate that the amount of DSBs in the nrdA101 recB strain was greater than that in the nrdA+ recB strain, suggesting an increase in the number of the stalled forks induced by the presence of defective NDP reductase at the permissive temperature.

TABLE 2.

The presence of the nrdA101 allele increases the level of RuvABC-dependent DSBs

| Strain | Relevant genotype | % Linear DNA (mean ± SD) | na |

|---|---|---|---|

| JK607 | nrdA+ | 4.58 ± 2.51 | 5 |

| JK626 | nrdA+recB | 15.18 ± 2.83 | 15 |

| JK707 | nrdA+recB ruvABC | 6.74 ± 2.60 | 5 |

| JS1018 | nrdA101 | 5.72 ± 1.41 | 4 |

| JS628 | nrdA101 recB | 24.79 ± 7.05 | 14 |

| JS705 | nrdA101 recB ruvABC | 5.94 ± 2.19 | 10 |

Number of independent determinations.

FIG. 2.

Representative profile of a PFGE experiment. JK626 (nrdA+ recB) (▴), JS628 (nrdA101 recB) (•), JK707 (nrdA+ recB ruvABC) (▵), and JS705 (nrdA101 recB ruvABC) (○) were used. Agarose plugs were prepared as described previously (20, 29). Gels were cut in 3-mm slices, the amount of [methyl-3H]thymidine present in each slice was measured, and the ratio of the total amount of [methyl-3H]thymidine in the lane was calculated for each slice. The gel origin is not shown; only the migrating DNA is shown. The position of the size marker is shown (Hansenula wingei; Bio-Rad). The amount of linear DNA was calculated from slice 4 to 12. Total proportions of migrating DNA in this experiment from slice 4 to 12 were 16.65% nrdA+ recB, 25.21% nrdA101 recB, 5.59% nrdA+ recB ruvABC, and 5.73% nrdA101 recB ruvABC.

DSBs in the nrdA101 recB strain are RuvABC dependent.

To establish the possible origin of the DSBs induced by the nrdA101 recB background, we investigated whether the formation of DSBs resulted from the action of the RuvABC resolvase (Fig. 1). The estimated DSB levels in the nrdA101 recB ruvABC and nrdA+ recB ruvABC strains were markedly lower than those in the respective Ruv+ counterpart strains (Table 2; Fig. 2). As RuvABC is a specific resolvase for HJs, according to the RFR model (Fig. 1), it generates DSBs at arrested replication forks in a recB-deficient background (29); these results indicate the occurrence of replication fork reversal in the nrdA101 recB mutant. As RFR is one of the mechanisms developed to restart the stalled replication forks, we could infer that the nrdA101 strain growing at 30°C increases the number of stalled replication forks that would proceed with the help of the RFR process in a Rec+-proficient context.

Testing the RFR model in the nrdA101 mutant.

The RFR model has three basic points (Fig. 1). The first is the formation of RuvABC-dependent DSBs in a recB-deficient strain, which we have shown above to occur. The second is the requirement for the RecBC activity to process double-strand ends generated at the reversed fork, as its absence would maintain the DSBs created by RuvABC activity. The third is that the lethality provoked by the inactivation of RecBC activity is reverted by the absence of RuvABC, since the activity of this resolvase will eventually conclude in DSBs if the activity of RecBC is absent (29). In order to test these effects on the growth of the nrdA101 mutant at the permissive temperature, we performed CFU experiments with the nrdA101 mutant strain under recA, recB, and/or ruvABC mutant conditions. In these experiments the number of CFU per colony was measured, reporting an aggregate measurement of both slower growth and lower viability of the strains. As shown in Table 3, inactivation of recB greatly compromised the growth of the nrdA101 mutant strain, and this detrimental effect was suppressed by the additional inactivation of ruvABC, as predicted by the RFR model (Fig. 1). This effect is specific for RecB deficiency, since it was not observed in the nrdA101 recA ruvABC mutant strain. Furthermore, RecB-induced detrimental growth is related to the presence of the nrdA101 allele, as the nrdA+ strain in the absence of RecA, RecB, or RuvABC recombination proteins is affected in all these cases to the same extent (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Growth of the nrdA101 mutant strain is affected by the absence of recombination proteins and PriA replication restart protein

| Strain | Relevant genotype | 30°C

|

37°C

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFU/ml (mean ± SD)a | CFU relative to that of nrdA101 strain | CFU/ml (mean ± SD)a | CFU relative to that of nrdA101 strain | ||

| JS1018 | nrdA101 | 4.8 × 107 ± 2.2 × 107 | 1 | 6.3 × 103 ± 0.4 × 103 | 1 |

| JS627 | nrdA101 recA | 1.6 × 107 ± 0.7 × 107 | 0.360 | 3.5 × 102 ± 1.4 × 102 | 0.070 |

| JS628 | nrdA101 recB | 2.5 × 106 ± 1.9 × 106 | 0.059 | 4.2 × 101 ± 0.4 × 101 | 0.008 |

| JS704 | nrdA101 ruvABC | 1.3 × 107 ± 0.2 × 107 | 0.301 | 2.3 × 102 ± 0.05 | 0.048 |

| JS705 | nrdA101 recB ruvABC | 3.7 × 107 ± 1.5 × 107 | 0.850 | 2.0 × 104 ± 0.1 × 104 | 4.138 |

| JS816 | nrdA101 recA ruvABC | 1.8 × 107 ± 0.8 × 107 | 0.420 | 0.9 × 102 ± 0.2 × 102 | 0.018 |

| JS891 | nrdA101 priA2 | 7.4 × 106 ± 3.4 × 106 | 0.171 | 0.5 × 101 ± 0.4 × 101 | 0.001 |

The number of independent experiments, done on different days, was between 8 and 24.

TABLE 4.

Growth of nrdA+ strains in the absence of recombination proteins

| Strain | Relevant genotype | CFU/ml (mean ± SD)a at 37°C | CFU relative to that of nrdA+ strain at 37°C | Relative CFU (mean ± SD), TdR at 2 μg/TdR at 5 μgb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JK607 | nrdA+ | 3.0 × 107 ± 1.5 × 107 | 1 | 1.08 ± 0.14 |

| JK625 | recA | 1.1 × 107 ± 0.4 × 107 | 0.34 | 0.41 ± 0.02 |

| JK626 | recB | 7.5 × 106 ± 3.3 × 106 | 0.25 | 0.62 ± 0.11 |

| JK706 | ruvABC | 1.3 × 107 ± 1.1 × 107 | 0.43 | 0.63 ± 0.08 |

| JK707 | recB ruvABC | 9.4 × 106 ± 3.4 × 106 | 0.31 | 1.12 ± 0.18 |

Individual colonies from rich medium plates were resuspended, and appropriate dilutions were plated on rich medium plates. The number of independent experiments, done on different days, was between 8 and 24.

Individual colonies from rich medium plates were resuspended, and appropriate dilutions were plated on M9 minimal plates containing either 2 μg/ml or 5 μg/ml of thymidine (TdR).

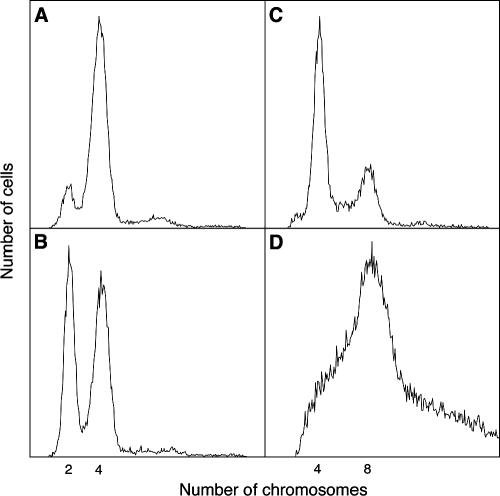

The results presented in this work also show that the effects on viability provoked by the absence of recombination protein in the nrdA101 background were enhanced at 37°C (Table 3). Flow cytometry measurements show that the nrdA101 mutant strain is unable to complete ongoing chromosomal replication at this semirestrictive temperature after the inhibition of new rounds of chromosomal replication by the addition of rifampin (Fig. 3). From runout experiments, the value of the C period for the nrdA101 strain at 37°C was calculated to be 218 min, but as chromosomal replication could not finish at this temperature, this C period value is even underestimated. These effects were most likely due to the high frequency of stalled forks in the nrdA101 mutant. To verify this idea, the DSB level in the nrdA101 recB strain growing at 37°C would have to be determined. We were unable to do this because overnight cultures of this strain were not reproducible and the strain could not maintain balanced growth at this semirestrictive temperature. In support of this observation, the priA2 allele had a marked detrimental effect when combined with the nrdA101 allele at 37°C relative to 30°C (Table 3). This indicates that the presence of the PriA protein is an absolute requirement for the NDP-reductase defective mutant to grow at a semirestrictive temperature.

FIG. 3.

DNA content per cell measured by flow cytometry after 4 h of incubation in the presence of rifampin and cephalexin in the nrdA+ strain growing at 30°C (A) and 37°C (B) and in the nrdA101 strain growing at 30°C (C) and 37°C (D).

An increase in DSBs is unrelated to reduction of the dNTP supply.

As dNTP synthesis is deficient in the nrdA101 mutant strain even at 30°C (6), it might be thought that the low supply of DNA precursors could be the cause of the lengthening of the C period and of the frequent stalled forks observed in the mutant. To test this possibility, we mimicked the situation by testing the level of stalled forks under conditions of reduced TTP supply in the presence of wild-type NDP reductase. We measured DSBs in the nrdA+ recB thyA and nrdA+ recB ruvABC thyA strains in the presence of thymidine at 5 μg/ml (optimal concentration) and 2 μg/ml (suboptimal concentration) at 30°C. Under these conditions, the generation times for the nrdA+ strain were not greatly affected, being 75 min in the presence of thymidine at 5 μg/ml and 86 min in the presence of thymidine at 2 μg/ml; however, the estimated lengths of the C periods were 98 min and 151 min, respectively (see “Determination of the C period” above). Data on linear DNA showed the RuvABC-dependent DSB levels to be similar under the two conditions (Table 5), therefore indicating that there is the same level of arrested replication forks in the nrdA+ recB strain growing with either 5 μg/ml or 2 μg/ml of thymidine. If lengthening of the C period in nrdA101 mutant strain were accounted for solely by the reduced activity of the NDP reductase, an increased formation of DSBs under thymidine limitation would be expected. As lengthening the C period by reducing the TTP supply does not increase DSBs (Table 5), this suggests that the increase in the level of stalled forks observed in an nrdA101 strain would not be attributed to the limiting activity of NDP reductase as an dNTP provider. We also performed CFU experiments with the nrdA+ strain under recB and/or ruvABC inactivation growing in minimal medium containing 2 μg/ml or 5 μg/ml of thymidine. We observed that the viability of the nrdA+ recombination-deficient strains was not greatly affected by the lowering of TTP supply (Table 4), in agreement with the similar DSB levels obtained with different thymidine concentrations (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Limitation of TTP supply does not increase the level of DSBs in the presence of wild-type NDP reductase

| Strains | Relevant genotype | Thymidine (μg) | % Linear DNA (mean ± SD) | na |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JK626 | nrdA+recB | 5 | 15.18 ± 2.83 | 15 |

| JK707 | nrdA+recB ruvABC | 5 | 6.74 ± 2.60 | 5 |

| JK626 | nrdA+recB | 2 | 17.31 ± 5.81 | 3 |

| JK626 | nrdA+recB ruvABC | 2 | 1.75 ± 0.37 | 2 |

Number of independent determinations.

DISCUSSION

Defective NDP reductase encoded by the nrdA101 allele slows chromosomal replication, and the limited NDP reductase activity reported for this mutant could account for this phenotype. In addition to being the only specific provider of dNTP in E. coli, the NDP reductase has been proposed to be a component of the replication hyperstructure, and this dual role opens a new option to explain the lengthening of the C period observed in the nrdA101 mutant. In this work we explored the possibility that structural alteration of the enzyme could contribute to this phenotype by affecting the replication hyperstructure. One of the consequences of this hypothesis might be a high frequency of replication fork arrest in the nrdA101 mutant strain. Stalled replication forks are known to be susceptible to breakage, but DSBs can be detected only if broken replication forks are not repaired. In this work we used the quantification of DSBs in a recB-deficient background as the experimental approach to study the occurrence of replication fork arrest in the nrdA101 mutant strain.

We showed the nrdA101 recB mutant strain to have an increase of DSBs compared with the nrdA+ recB strain (Table 2; Fig. 2). We found that in the nrdA101 recB strain the induced DSBs are dependent on RuvABC activity, indicating that they are generated after resolution of an HJ created by RFR at the stalled fork. According to the RFR model, the occurrence of RuvABC-dependent DSBs in a recB-deficient background would be an indicator of the amount of stalled replication forks that have been regressed and likely restarted in a rec+ background (Fig. 1) (29). Therefore, the results indicate that in the presence of defective NDP reductase, there is an increase in the number of stalled replication forks that would proceed with the help of RFR in a rec+ background. The observed effects on the growth of rec-deficient mutants supported the occurrence of RFR in the nrdA101 context, as follows. (i) The detriment of the growth of the nrdA101 recB mutant strain was greater than that of the nrdA101 recA and nrdA101 ruvABC recombination mutants (Table 3). We showed that the negative effect observed in an nrdA101 recB strain was provoked by the presence of the NDP reductase encoded by the nrdA101 allele, as in the nrdA+ context the absence of RecA, RecB, or RuvABC proteins had results of similar magnitude (Table 4). (ii) We found a specific recovery of the nrdA101 recB mutant growth under RuvABC inactivation (Table 3). (iii) The requirement for the recombination proteins and PriA in the nrdA101 background was magnified at 37°C. PriA is the main E. coli replication restart protein and is essential for growth under any condition that increases the frequency of fork arrests (5, 8, 28). We have shown that at 37°C, chromosomal replication in the nrdA101 strain is unable to finish in the presence of rifampin, and the underestimated C period is longer than at the permissive temperature. We could not verify the level of DSBs at 37°C in the nrdA101 recB strain, but all these results together suggest that the nrdA101 mutant strain at the semirestrictive temperature contains a high level of stalled forks.

NDP reductase encoded by nrdA101 allele has been shown to have a reduced activity as a dNTP provider even at 30°C (6, 16), and this effect could explain the lengthening of the C period observed in the nrdA101 mutant strain at a permissive temperature, assuming that a limited dNTP pool would be the cause of the increase in the amount of stalled replication forks reported in this work (Table 2). To determine whether the increase in the number of stalled forks was caused by the limitation of the dNTP supply, we mimicked this situation without altering the NDP reductase structure by using thymine limitation in an nrdA+ isogenic strain. This growth condition can be used to manipulate the C period under balanced growth, as it generates a reduction in the TTP pool and consequently the lengthening of the C period in the presence of a wild-type NDP reductase (26, 32). We performed PFGE experiments with the nrdA+ recB thyA strain growing with a limited thymidine supply. Our results show that the level of DSBs did not change in the nrdA+ strain growing at a suboptimal thymidine concentration (Table 5), and that the viability of the recombination mutants was not greatly affected by the lowering of the TTP supply (Table 4). Thymine limitation is not a pathological state of the cell (33). As far as we know, the effects of thymine limitation are related to or are consequences of the lowering of the TTP pool, that is, lowering of the chromosomal replication rate (i.e., increasing the C period) (see Table 1 in reference 33). Therefore, if the limiting activity of the NDP reductase would be causing the increase in the number of stalled forks in the nrdA101 mutant at 30°C by limiting the amount of dNTPs, then the limiting amount of TdR in the presence of wild type NDP reductase (achieved by thymidine limitation in an nrdA+ background) should be expected to have the same effect. We found that nrdA101 mutation induced DSBs, while thymine limitation in an nrdA+ background did not. Consequently, this would indicate that the increase in the level of stalled forks observed in the nrdA101 strain would not be caused by the limiting activity of NDP reductase as a dNTP provider.

The phenotype observed in the nrdA101 mutant was similar to that reported for replication mutants that inactivate enzymes involved in the progression of the fork: (i) the rep helicase mutant (20, 29), (ii) the holD mutant affected by one of the components of the γ complex of DNA polymerase III (ψ subunit) which in vivo may lead to the arrest of the entire replication machinery (4), and (iii) under partial inactivation of the α and β subunits of DNA polymerase III by incubation of dnaE(Ts) and dnaN(Ts) mutants, respectively, at 37°C (9). As described for the nrdA101 strain, all these mutants require RecBC to survive, and they undergo RFR, as high levels of RuvABC-dependent DSBs were detected in the absence of RecBCD activity. We propose the possibility that the increase in the level of stalled forks observed in the nrdA101 strain was due to an altered progression of the replication fork as a consequence of the lability of the replication hyperstructure in the presence of an nrdA101-encoded NDP reductase.

Mathews and coworkers proposed, and have extensively described, the association of the nucleotide metabolism enzymes in a dNTP-synthesizing complex, explaining channeling of the biosynthesis and compartmentation of the precursors in T4 metabolism (13, 17-19, 27). Recently, new approaches supporting the associations between dNTP synthesis enzymes, DNA, and the replication complex in T4-infected cells (14) and in E. coli (10, 24) have been described. The data provided by the present work would be consistent with the presence of the NDP reductase at the replication fork in vivo and represent independent support for the presence of NDP reductase as a structural and functional component of the replication hyperstructure (10), as they show the occurrence of replication fork arrest in the presence of NDP reductase encoded by nrdA101 allele. Given the possible interaction of NDP reductase with the replisome, we suggest that the nrdA101 strain could generate a less processive replication hyperstructure that would contribute to the lengthening of the C period by impairing the progression of the replication forks.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Bénédicte Michel for bacterial strains, experimental support, and careful reading of the manuscript. We especially thank Encarna Ferrera for her technical help.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología (BMC2002-00830) and the Junta de Extremadura (2PR04A036).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bidnenko, V., S. D. Ehrlich, and B. Michel. 2002. Replication fork collapse at replication terminator sequences. EMBO J. 21:3898-3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bierne, H., and B. Michel. 1994. When replication forks stop. Mol. Microbiol. 13:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eklund, H., U. Uhlin, M. Farnegardh, D. T. Logan, and P. Nordlund. 2001. Structure and function of the radical enzyme ribonucleotide reductase. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 77:177-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flores, M. J., H. Bierne, S. D. Ehrlich, and B. Michel. 2001. Impairment of lagging strand synthesis triggers the formation of a RuvABC substrate at replication forks. EMBO J. 20:619-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flores, M. J., S. D. Ehrlich, and B. Michel. 2002. Primosome assembly requirement for replication restart in the Escherichia coli holDG10 replication mutant. Mol. Microbiol. 44:783-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuchs, J. A., H. O. Karlstrom, H. R. Warner, and P. Reichard. 1972. Defective gene product in dnaF mutant of Escherichia coli. Nat. New Biol. 238:69-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grigorian, A. V., R. B. Lustig, E. C. Guzmán, J. M. Mahaffy, and J. W. Zyskind. 2003. Escherichia coli cells with increased levels of DnaA and deficient in recombinational repair have decreased viability. J. Bacteriol. 185:630-644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grompone, G., S. D. Ehrlich, and B. Michel. 2003. Replication restart in gyrB Escherichia coli mutants. Mol. Microbiol. 48:845-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grompone, G., M. Seigneur, S. D. Ehrlich, and B. Michel. 2002. Replication fork reversal in DNA polymerase III mutants of Escherichia coli: a role for the β clamp. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1331-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guzmán, E. C., J. L. Caballero, and A. Jiménez-Sánchez. 2002. Ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase is a component of the replication hyperstructure in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 43:487-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horiuchi, T., Y. Fujimura, H. Nishitani, T. Kobayashi, and M. Hidaka. 1994. The DNA replication fork blocked at the Ter site may be an entrance for the RecBCD enzyme into duplex DNA. J. Bacteriol. 176:4656-4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horiuchi, T., H. Nishitani, and T. Kobayashi. 1995. A new type of E. coli recombinational hotspot which requires for activity both DNA replication termination events and the Chi sequence. Adv. Biophys. 31:133-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim, J., R. Shen, M. C. Olcott, I. Rajagopal, and C. K. Mathews. 2005. Adenylate kinase of Escherichia coli, a component of the phage T4 dNTP synthetase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 280:28221-28229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim, J., L. J. Wheeler, R. Shen, and C. K. Mathews. 2005. Protein-DNA interactions in the T4 dNTP synthetase complex dependent on gene 32 single-stranded DNA-binding protein. Mol. Microbiol. 55:1502-1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuzminov, A. 1995. Instability of inhibited replication forks in E. coli. Bioessays 17:733-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manwaring, J. D., and J. A. Fuchs. 1979. Relationship between deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate pools and deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in an nrdA mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 138:245-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathews, C. K. 1993. Enzyme organization in DNA precursor biosynthesis. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 44:167-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathews, C. K. 1991. Metabolite channelling in deoxyribonucleotide and DNA biosynthesis. J. Theor. Biol. 152:25-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathews, C. K., and N. K. Sinha. 1982. Are DNA precursors concentrated at replication sites? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:302-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michel, B., S. D. Ehrlich, and M. Uzest. 1997. DNA double-strand breaks caused by replication arrest. EMBO J. 16:430-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michel, B., G. Grompone, M. J. Flores, and V. Bidnenko. 2004. Multiple pathways process stalled replication forks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:12783-12788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course on bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 23.Molina, F., A. Jiménez-Sánchez, and E. C. Guzmán. 1998. Determining the optimal thymidine concentration for growing Thy− Escherichia coli strains. J. Bacteriol. 180:2992-2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molina, F., and K. Skarstad. 2004. Replication fork and SeqA focus distributions in Escherichia coli suggest a replication hyperstructure dependent on nucleotide metabolism. Mol. Microbiol. 52:1597-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan, A. R., and A. Severini. 1990. Interconversion of replication and recombination structures: implications for terminal repeats and concatemers. J. Theor. Biol. 144:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pritchard, R. H. 1974. Review lecture on the growth and form of a bacterial cell. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B 267:303-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddy, G. P., and C. K. Mathews. 1978. Functional compartmentation of DNA precursors in T4 phage-infected bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 253:3461-3467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandler, S. J., and K. J. Marians. 2000. Role of PriA in replication fork reactivation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seigneur, M., V. Bidnenko, S. D. Ehrlich, and B. Michel. 1998. RuvAB acts at arrested replication forks. Cell 95:419-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skarstad, K., H. B. Steen, and E. Boye. 1985. Escherichia coli DNA distributions measured by flow cytometry and compared with theoretical computer simulations. J. Bacteriol. 163:661-668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sueoka, N., and H. Yoshikawa. 1965. The chromosome of Bacillus subtilis. I. Theory of marker frequency analysis. Genetics 52:747-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaritsky, A., and R. H. Pritchard. 1971. Replication time of the chromosome in thymineless mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 60:65-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaritsky, A., C. L. Woldringh, M. Einav, and S. Alexeeva. 2006. Use of thymine limitation and thymine starvation to study bacterial physiology and cytology. J. Bacteriol. 188:1667-1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]