Abstract

The two-component system MtrBA is involved in the osmostress response of Corynebacterium glutamicum. MtrB was reconstituted in a functionally active form in liposomes and showed autophosphorylation and phosphatase activity. In proteoliposomes, MtrB activity was stimulated by monovalent cations used by many osmosensors for the detection of hypertonicity. Although MtrB was activated by monovalent cations, they lead in vitro to a general stabilization of histidine kinases and do not represent the stimulus for MtrB to sense hyperosmotic stress.

The ability of bacteria to sense and respond to environmental changes is a prerequisite for survival in their natural habitats. The most frequent bacterial sensory and signal transduction systems are two-component systems. Prototypical two-component systems consist of a membrane-bound histidine protein kinase and a cytoplasmic response regulator generally acting as a transcription factor. The homodimeric histidine protein kinase, which is regulated by environmental stimuli, autophosphorylates in trans in an ATP-dependent manner at a conserved histidine residue, creating a high-energy phosphoryl group that is subsequently transferred to an aspartate residue of the response regulator. In turn, this transfer affects the DNA-binding properties of the response regulator. Most histidine kinases also possess phosphatase activity that allows the dephosphorylation of the cognate response regulator. The balance between the autokinase and the phosphatase activity of the sensor kinase is thought to control the net phosphorylation of the response regulator (23, 24).

Corynebacterium glutamicum, a gram-positive soil bacterium, contains 13 two-component systems. Recently, a set of 12 strains was constructed in order to analyze the individual functions of these systems (15, 17). One of these systems, the so-called MtrB-MtrA system, is highly conserved in sequence and genomic organization among actinobacteria (7, 17). The response regulator MtrA seems to be essential in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (29), whereas a single ΔmtrA deletion mutant as well as a ΔmtrAB double deletion mutant of C. glutamicum can be constructed (2, 17). The function of this system is still rather ill-defined, and different target genes in corynebacteria and mycobacteria have been described. In mycobacteria, MtrB-MtrA seems to be involved in the regulation of the cell wall permeability (3) and in cell cycle progression, since dnaA is under its control (6). In C. glutamicum, a number of genes involved in osmoregulation and peptidoglycan metabolism show altered mRNA levels in the ΔmtrAB mutant. RNA hybridization experiments revealed that the genes encoding three out of the altogether four osmoregulated compatible-solute carriers, namely, betP, proP, and lcoP, are under the control of MtrB-MtrA (17), suggesting that the MtrB-MtrA system is important for the osmotic stress response of C. glutamicum. MtrB seems to be able to detect the extent of osmotic stress, since the expression of the transporter genes was induced according to the extent of hyperosmotic stress, suggesting that MtrB acts as an osmosensor. Furthermore, the ΔmtrAB strain exhibited a radically changed cell morphology and was more sensitive to several antibiotics than the wild type (17). DNA array analysis revealed that genes encoding enzymes related to peptidoglycan metabolism were upregulated in the mutant, indicating that MtrB-MtrA has more than one sensing function in C. glutamicum. Meanwhile, the binding of MtrA to the promoters of mepA, betP, and proP has been shown previously, proving that MtrA is directly involved in the regulation of different cellular functions (2).

We are interested in the question of which physicochemical stimulus indicates the presence of hyperosmotic conditions, leading to the activation of MtrB. Recently, the sensing functions of some osmosensors in proteoliposomes, a system of lower complexity than the intact cell, have been successfully investigated (4, 10, 12, 20, 25). In this report, we describe the enzymatic characterization of the two-component system MtrB-MtrA in proteoliposomes. In this in vitro system, MtrB possesses all the relevant enzymatic activities of histidine protein kinases. Thus, it was interesting to investigate the influence of monovalent cations on the activity regulation of MtrB, since previously it has been shown that the internal cation concentration is used by several osmosensors as an indicator of hypertonicity.

Purification of MtrB and MtrA.

To characterize the MtrB-MtrA two-component system in vitro, it was necessary to isolate both protein components. The response regulator MtrA-His10 was purified to homogeneity from Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)/pET224b-mtrA (the expression vector pET224b-mtrA was kindly provided by M. Brocker and M. Bott and will be described in a separate publication) by using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity chromatography (chromatography equipment was obtained from QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). In order to construct expression plasmids allowing for the synthesis of MtrB fused at either the C-terminal or N-terminal end with Strep-tag II, mtrB was amplified by means of PCR using chromosomal DNA of C. glutamicum and the primers 5′-GACCGCGGTCTCGGCTCCATCTTCACC and 5′-GACCATGGTCCTGCTGCTCCCCTTCCC or 5′-GACCGCGGTCTCGGCTCCATCTTCACC and 5′-GACCATGGCTTCACTGCTGCTCCCCTTC. After digestion with PshaI, the fragments were ligated into the identically treated plasmids pASK-IBA3 and pASK-IBA7 (IBA, Göttingen, Germany) and sequenced for control. The resulting plasmids were designated pIBA3-mtrB-strep and pIBA7-strep-mtrB, respectively. After transformation, MtrB synthesis in the respective BL21(DE3)/pIBA derivative right before and after the induction of the mtrB gene with 40 μg of anhydroxy tetracycline/liter was monitored by using antibodies raised against the Strep-tag II. Immediately after induction, E. coli started to synthesize MtrB as indicated by a protein band corresponding to the expected molecular mass of 56 kDa, and truncated forms of MtrB were also observed (Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This synthesis occurred independently of factors such as whether the Strep-tag II was fused to the N- or C-terminal end of MtrB or whether different growth temperatures, anhydroxy tetracycline concentrations, or E. coli strains were used (data not shown). The yield of C-terminally tagged MtrB was higher than that of N-terminally tagged MtrB; thus, this form was used for purification. Nevertheless, all experiments described below were carried out with both MtrB derivatives with identical results, proving that the Strep-tag did not interfere with MtrB regulation (data not shown).

After the induction of MtrB synthesis, membranes were isolated and MtrB was solubilized with 2% n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside and purified by means of Strep-tag affinity chromatography basically as described recently for the uptake carrier BetP (20). Obviously, the degradation bands of MtrB carried the Strep-tag II, since they were copurified. In order to verify that intact MtrB was present, the N-terminal sequence of the protein represented by the band corresponding to the highest molecular mass (see arrow in Fig. S1B in the supplemental material) was determined by Edman sequencing, proving that this band corresponded to full-length MtrB.

Characterization of the kinase and phosphatase activity of MtrB.

After affinity chromatography, MtrB was reconstituted into liposomes prepared from E. coli phospholipids as described by Rübenhagen et al. (20). The histidine kinase activity of MtrB in the presence of 0.22 μM [γ-33P]ATP was measured. For this purpose, 1.6 to 2 μg of frozen MtrB in phosphorylation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) was slowly thawed at room temperature and diluted to 950 μl. Proteoliposomes were extruded 14 to 20 times through polycarbonate filters (pore diameter, 400 nm), harvested by ultracentrifugation (337,000 × g), and concentrated in phosphorylation buffer supplemented with 1 mM dithiothreitol and 5 mM MgCl2 to a final volume of 10 μl. At the indicated time points after the addition of [γ-33P]ATP, the reaction was stopped with sodium dodecyl sulfate buffer (see Fig. 1). Liposomal MtrB was subjected to gel electrophoresis, and the degree of phosphorylation was detected by autoradiography by using phosphorimaging plates (BAS-IP MP 2025; Fujifilm, Düsseldorf, Germany). A linear, time-dependent phosphorylation of full-length and truncated MtrB for at least 30 min was detected (data not shown). However, MtrB solubilized in 0.5% n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside was not phosphorylated under identical conditions (data not shown), indicating that the histidine kinase has to be integrated into a lipid bilayer in order to be active, as found recently with other histidine protein kinases (8, 11). The ATP affinity was determined by varying the [γ-33P]ATP concentrations from 1 to 10,000 μM ATP, leading to a Km of 0.3 mM (data not shown), which is similar to that for the reconstituted form of the histidine protein kinase DcuS of E. coli (8).

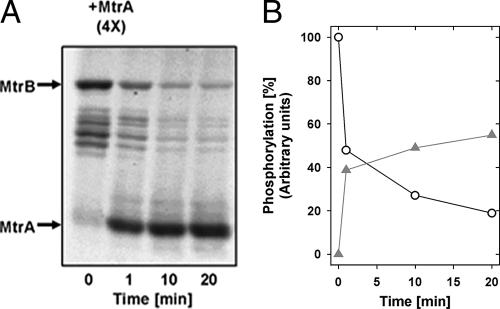

FIG. 1.

Phosphoryl transfer from MtrB to MtrA. Proteoliposomes containing MtrB were mixed with [γ-33P]ATP for 10 min before MtrA was added to the mixture in a 4:1 ratio of MtrA and MtrB. Samples were taken at the indicated time points after the addition of MtrA. (A) Autoradiogram of the phosphotransfer reaction. (B) Quantification of the phosphorelay. The degree of phosphorylation of MtrB before the addition of MtrA was set at 100%. Since in the presence of MtrA, the shorter degradation fragments of MtrB also undergo the phosphotransfer reaction, all bands of MtrB were used for the quantification of the phosphoryl signal. Circles, phosphorylation of MtrB; triangles, phosphorylation of MtrA. The data are a typical example of results from more than four independent experiments performed with reconstituted MtrB.

We further investigated the phosphoryl group transfer from MtrB to MtrA (Fig. 1). For this purpose, MtrB was phosphorylated with 0.22 μM [γ-33P]ATP in proteoliposomes for 10 min at 30°C before MtrA was added in a 4-to-1 ratio of MtrA to MtrB (132 pmol and 33 pmol). Immediately (1 min) after the addition of MtrA, a significant transfer of the phosphoryl residue from MtrB to MtrA occurred as indicated by a reduction of MtrB phosphorylation of approximately 50%, which proceeded further within 20 min to a decrease of phosphorylation of about 80%. Once phosphorylated, MtrA seems to be highly stable compared to other response regulators, like DcuR and KdpE (8, 18, 28). The prolonged linear increase of the autophosphorylation signal of MtrB, which had not decreased at up to 30 min, and the persisting phosphorylation of MtrA are in agreement with the observation that after a severe hyperosmotic shock, the induction of the expression of betP, lcoP, and proP in C. glutamicum was also found to be increased at up to 180 min after the application of the osmotic shock (17).

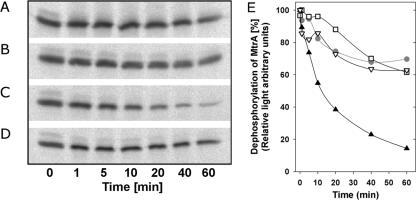

Many histidine kinases have, besides the autophosphorylation activity, the ability to dephosphorylate their cognate response regulator. To test whether this is true for MtrB, phosphorylated MtrA (16 μg) was produced as described in the legend to Fig. 1. After 20 min, phosphorylated MtrA was separated from MtrB liposomes by ultracentrifugation; subsequently, the residual ATP and ADP were removed by gel filtration with NAP-5 columns (Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany). Phosphorylated MtrA was adjusted with reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.5 M KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol) containing 1.6 mM ADP if indicated (legend to Fig. 2) before inverted membrane vesicles (IMV; 1 mg of total protein) were added. The IMV were prepared from the ATPase-deficient E. coli strain DK8 (13) carrying pIBA3-mtrB-strep. The dephosphorylation reaction was performed for 1 to 60 min at 30°C (Fig. 2). If phosphorylated MtrA was mixed solely with reaction buffer, a decay of the phosphorylation signal of about 30% occurred within 60 min (Fig. 2A and E), representing a weak MtrB-independent dephosphorylation of MtrA. The signal decay was very similar if MtrB-containing IMV were added (Fig. 2B and E). Thus, MtrB seems not to be active in the phosphatase mode under these conditions. If 1.6 mM ADP together with MtrB-containing IMV were added, a signal decay of about 90% was detected within 60 min (Fig. 2C and E). This activity could be attributed solely to MtrB, because under identical assay conditions (Fig. 2D and E) no phosphatase activity was present when MtrB-free IMV were used (Fig. 2D). MtrB seems to switch to the phosphatase mode only in the presence of ADP, an observation which was also described for EnvZ and PhoQ reconstituted into proteoliposomes (10, 22).

FIG. 2.

Dephosphorylation of MtrA. To measure the phosphatase activity of MtrB, phosphorylated MtrA was prepared as described in the legend to Fig. 1. After the separation of MtrA from the proteoliposomes and residual ATP and ADP, phosphorylated MtrA was incubated for 60 min in the presence and absence of MtrB. (A) Influence of the reaction buffer on the dephosphorylation of phosphorylated MtrA. (B) Influence of MtrB-containing IMV on the dephosphorylation of phosphorylated MtrA. (C) Dephosphorylation of phosphorylated MtrA in the presence of MtrB-containing IMV and 1.6 mM ADP. (D) Dephosphorylation of phosphorylated MtrA in the presence of MtrB-free IMV and 1.6 mM ADP. (E) Quantification of the radioactive signals of phosphorylated MtrA shown in panels A to D. Circles, panel A; squares, panel B; closed triangles, panel C; open, inverted triangles, panel D. The data set is an example of findings from two independent experiments with almost identical results.

Stimulation of MtrB activity by monovalent cations.

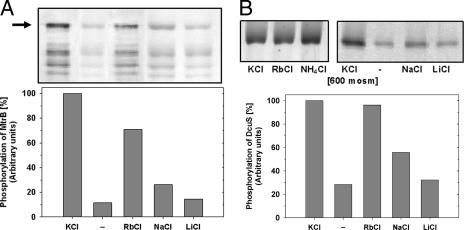

The osmostress-induced expression of the genes encoding uptake systems of compatible solutes, namely, betP, proP, and lcoP, is under the control of the MtrB-MtrA system in a dose-dependent manner (17), suggesting that MtrB seems to sense changes in the external osmolality. Recently, in vitro analyses of some osmosensors shed light on the question of which physicochemical parameter functions as an indicator of hyperosmotic stress. This issue was studied with the histidine protein kinases KdpD and EnvZ, the secondary transporters BetP and ProP, and the ABC transporter OpuA (4, 10, 12, 21, 25). Although very different with respect to bacterial origins (E. coli, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Lactococcus lactis, and C. glutamicum) as well as functions (transcriptional regulation and solute uptake) and structures, these systems interestingly seem to perceive similar internal signals as indicators of hyperosmotic stress, namely, changes in the internal ionic strength (KdpD, EnvZ, and OpuA) and/or changes in the internal solute (ProP) or K+ (BetP) concentration. It was tempting to speculate that MtrB also may respond to a similar signal. Thus, we tested the influence of KCl, RbCl, NaCl, LiCl, and NH4Cl on the autophosphorylation activity of MtrB (Fig. 3A). It turned out that cations with similar properties, like K+, Rb+, and NH4+ (data not shown for NH4+), stimulated MtrB, whereas Na+ and Li+ were either less effective or not effective. These results also proved that the cation and not the chloride anion was responsible for MtrB activation, since LiCl failed to stimulate MtrB.

FIG. 3.

Influence of different monovalent cations on the phosphorylation activities of MtrB and DcuS in liposomes. The reaction was performed for 10 min after the addition of [γ-33P]ATP. (A) Influence of different monovalent cations on the autokinase activity of MtrB (upper panel, autoradiogram; lower panel, quantification of the phosphorylation activity indicated above). (B) Influence of different monovalent cations on the autokinase activity of DcuS (upper panel, autoradiogram; lower panel, quantification of the phosphorylation activity indicated above). The data sets are examples of findings from at least two independent experiments with almost identical results. −, no cations; mosm, milliosmoles.

In order to distinguish between two principal possibilities, namely, (i) MtrB's being specifically activated by cations and (ii) cations' influencing the autophosphorylation of reconstituted histidine protein kinases in general, we used the histidine kinase DcuS of E. coli as a control. The two-component system DcuS-DcuR regulates the expression of genes involved in C4 dicarboxylate metabolism in response to the external presence of fumarate or other C4 dicarboxylates under anaerobic conditions (9, 14). DcuS was purified and reconstituted as recently described (8). Interestingly, reconstituted DcuS turned out to be identically activated by monovalent cations (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, a basic potassium concentration of 20 mM seemed to be necessary to render DcuS susceptible to activation by fumarate (data not shown), since in the absence of K+ no activation was detected. These results indicate either that DcuS has, besides fumarate sensing, additional sensing functions or that cations do not act specifically on MtrB but may have in vitro a rather general stimulating effect on histidine kinases. In order to test whether the expression of the target genes of the DcuS-DcuR system is stimulated under hyperosmotic conditions, we measured the expression of dcuB, encoding a fumarate uptake system, after a sudden osmotic upshift. For this purpose, E. coli strain IMW237 (30), which carries a chromosomally inserted dcuB::lacZ fusion, was used. The expression of the fusion is tightly regulated under anaerobic conditions by the DcuS-DcuR two-component system (30). The E. coli cells were grown anaerobically on glycerol plus dimethyl sulfoxide or N,N-dimethyldodecylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) in M9 medium (1). After a shift to media supplemented with various solutes in order to increase the external osmolality to approximately 400 to 800 mosmol/kg (Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), the expression of dcuB was quantified by measuring the β-galactosidase activity in exponentially growing cells according to the method of Miller (16). The promoter of dcuB was induced 7.7- and 8.9-fold by the addition of 50 mM sodium fumarate and Tris-fumarate, respectively. In contrast, no change in the expression was detected when the osmolality was increased to 400 to 800 osmol/kg by sorbitol, NaCl, or KCl. Moreover, in hyperosmotic medium, no induction of dcuB expression in E. coli in the presence of fumarate was observed. Obviously, hyperosmotic conditions, which lead to increased internal K+ concentrations in E. coli (5, 19), do not induce the expression of the DcuS-DcuR-dependent dcuB::lacZ fusion, whereas fumarate causes a specific induction.

We thus conclude that the stimulation of DcuS activity by cations may not reflect a physiologically relevant event but rather a general effect of cations on the DcuS kinase activity in liposomes. This interpretation is supported by a transcriptome analysis of E. coli, in which the genes under the control of DcuS-DcuR were not affected upon a hyperosmotic shock (27). The fact that monovalent cations similarly stimulate DcuS and MtrB strongly argues against MtrB's being activated by these ions in a specific and physiologically relevant manner. We suggest that for so-far-unknown reasons, histidine protein kinases, at least after solubilization, purification, and reconstitution into proteoliposomes, require elevated concentrations of monovalent cations to induce and/or stabilize an active protein conformation. This hypothesis is in line with the observation that EnvZ and KdpD, present either in IMV or in proteoliposomes in an inside-out orientation, are efficiently activated by K+ (10, 18, 26,). In the case of KdpD the stimulation by K+ is lost only in right-side-out membrane vesicles (12), in which, however, both the natural membrane surroundings of KdpD and its orientation are identical to those in intact E. coli cells. This may be the reason why the regulation of KdpD in right-side-out membrane vesicles was similar to that found in vivo. On the basis of these observations, we suggest that K+ has a basic stimulating effect on reconstituted histidine protein kinases, although this effect may not be relevant in vivo. Moreover, it is concluded that MtrB uses, relative to the known osmosensors, a different signal as a measure of hyperosmotic conditions. The correct physical stimulus still has to be defined, and DcuS may serve as an appropriate control to distinguish between specific and nonspecific stimuli.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for financial support.

We also thank Kirsten Jung and Ralf Hermann for helpful suggestions, Karlheinz Altendorf and Gabriele Deckers-Hebestreit for kindly providing the ATP synthase-deficient E. coli strain DK8, and finally Michael Bott and Melanie Brocker for the gift of pET224b-mtrA-10-His.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 February 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 2002. Short protocols in molecular biology. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany.

- 2.Brocker, M., and M. Bott. 2006. Evidence for activator and repressor functions of the response regulator MtrA from Corynebacterium glutamicum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 264:205-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cangelosi, G. A., J. S. Do, R. Freeman, J. G. Bennett, M. Semret, and M. A. Behr. 2006. The two-component regulatory system mtrAB is required for morphotypic multidrug resistance in Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:461-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culham, D. E., J. Henderson, R. A. Crane, and J. M. Wood. 2003. Osmosensor ProP of Escherichia coli responds to concentration, chemistry, and molecular size of osmolytes in the proteoliposome lumen. Biochemistry 42:410-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dinnbier, U., E. Limpinsel, R. Schmid, and E. P. Bakker. 1988. Transient accumulation of potassium glutamate and its replacement by trehalose during adaptation of growing cells of Escherichia coli K-12 to elevated sodium chloride concentrations. Arch. Microbiol. 150:348-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fol, M., A. Chauhan, N. K. Nair, E. Maloney, M. Moomey, C. Jagannath, M. V. Madiraju, and M. V. Rajagopalan. 2006. Modulation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis proliferation by MtrA, an essential two-component response regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 60:643-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoskisson, P. A., and M. I. Hutchings. 2006. MtrAB-LpqB: a conserved three-component system in actinobacteria? Trends Microbiol. 14:444-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janausch, I. G., I. Garcia-Moreno, and G. Unden. 2002. Function of DcuS from Escherichia coli as a fumarate-stimulated histidine protein kinase in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 277:39809-39814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janausch, I. G., E. Zientz, Q. H. Tran, A. Kröger, and G. Unden. 2002. C4-dicarboxylate carriers and sensors in bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1553:39-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung, K., K. Hamann, and A. Revermann. 2001. K+ stimulates specifically the autokinase activity of purified and reconstituted EnvZ of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 276:40896-40902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung, K., B. Tjaden, and K. Altendorf. 1997. Purification, reconstitution, and characterization of KdpD, the turgor sensor of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 272:10847-10852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung, K., M. Veen, and K. Altendorf. 2000. K+ and ionic strength directly influence the autophosphorylation activity of the putative turgor sensor KdpD of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 275:40142-40147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klionsky, D. J., W. S. Brusilow, and R. S. Simoni. 1984. In vivo evidence for the role of the epsilon subunit as an inhibitor of the proton-translocating ATPase of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 160:1055-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kneuper, H., I. G. Janausch, V. Vijayan, M. Zweckstetter, V. Bock, C. Griesinger, and G. Unden. 2005. The nature of the stimulus and of the fumarate binding site of the fumarate sensor DcuS of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 280:20596-20603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kocan, M., S. Schaffer, T. Ishige, U. Sorger-Herrmann, V. F. Wendisch, and M. Bott. 2006. Two-component systems of Corynebacterium glutamicum: deletion analysis and involvement of the PhoS-PhoR system in the phosphate starvation response. J. Bacteriol. 188:724-732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 17.Möker, N., M. Brocker, S. Schaffer, R. Krämer, S. Morbach, and M. Bott. 2004. Deletion of the genes encoding the MtrA-MtrB two-component system of Corynebacterium glutamicum has a strong influence on cell morphology, antibiotics susceptibility and expression of genes involved in osmoprotection. Mol. Microbiol. 54:420-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakashima, K., A. Sugiura, H. Momoi, and T. Mizuno. 1992. Phosphotransfer signal transduction between two regulatory factors involved in the osmoregulated kdp operon in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1777-1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Record, M. T., Jr., E. S. Courtnay, D. S. Cayley, and H. J. Gutman. 1998. Responses of E. coli to osmotic stress: large changes in amounts of cytoplasmic solutes and water. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:143-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rübenhagen, R., H. Jung, R. Krämer, and S. Morbach. 2000. Osmosensor and osmoregulator properties of the betaine carrier BetP from Corynebacterium glutamicum in proteoliposomes. J. Biol. Chem. 275:735-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rübenhagen, R., S. Morbach, and R. Krämer. 2001. The osmoreactive betaine carrier BetP from Corynebacterium glutamicum is a sensor for cytoplasmic K+. EMBO J. 20:5412-5420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanowar, S., and H. Le Moual. 2005. Functional reconstitution of the Salmonella typhimurium PhoQ histidine kinase sensor in proteoliposomes. Biochem. J. 390:769-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stock, A. M., V. L. Robinson, and P. N. Goudreau. 2000. Two component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:183-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stock, J. B., A. J. Ninfa, and A. M. Stock. 1989. Protein phosphorylation and regulation of adaptive responses in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 53:450-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Heide, T., M. C. Stuart, and B. Poolman. 2001. On the osmotic signal and osmosensing mechanism of an ABC transport system for glycine betaine. EMBO J. 20:7022-7032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voelkner, P., W. Puppe, and K. H. Altendorf. 1993. Characterization of the KdpD protein, the sensor kinase of the K+-translocating Kdp system of Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 217:1019-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber, A., and K. Jung. 2002. Profiling early osmostress-dependent gene expression in Escherichia coli using DNA macroarrays. J. Bacteriol. 184:5502-5507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto, K., K. Hirao, T. Oshima, H. Aiba, R. Utsumi, and A. Ishihama. 2005. Functional characterization in vitro of all two component signal transduction systems from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 280:1448-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zahrt, T. C., and V. Deretic. 2000. An essential two-component signal transduction system in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 182:3832-3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zientz, E., J. Bongaerts, and G. Unden. 1998. Fumarate regulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli by the DcuSR (dcuSR) two-component regulatory system. J. Bacteriol. 180:5421-5425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.