Abstract

Legionella pneumophila and other pathogenic Legionella species multiply inside protozoa and human macrophages by using the Icm/Dot type IV secretion system. The IcmQ protein, which possesses pore-forming activity, and IcmR, which functions as its chaperone, are two essential components of this system. It was previously shown that in 29 Legionella species, a large hypervariable-gene family (fir genes) is located upstream from a conserved icmQ gene, but although nonhomologous, the FIR proteins were found to function similarly together with their corresponding IcmQ proteins. Alignment of the regulatory regions of 29 fir genes revealed that they can be divided into three regulatory groups; the first group contains a binding site for the CpxR response regulator, which was previously shown to regulate the L. pneumophila fir gene (icmR); the second group, which includes most of the fir genes, contains the CpxR binding site and an additional regulatory element that was identified here as a PmrA binding site; and the third group contains only the PmrA binding site. Analysis of the regulatory region of two fir genes, which included substitutions in the CpxR and PmrA consensus sequences, a controlled expression system, as well as examination of direct binding with mobility shift assays, revealed that both CpxR and PmrA positively regulate the expression of the fir genes that contain both regulatory elements. The change in the regulation of the fir genes that occurred during the course of evolution might be required for the adaptation of the different Legionella species to their specific environmental hosts.

Legionella pneumophila is the most common causative agent of Legionnaires’ disease, and it was shown to be able to grow within and kill human macrophages, as well as free-living amoebae (22, 42). The genome of L. pneumophila was shown to contain 25 genes, named the icm/dot genes, which form a type IV secretion complex (44, 45, 51, 52), through which effector proteins are translocated into infected host cells (4, 7, 27, 28, 34-36, 49). Two of the icm/dot genes encode the IcmR and IcmQ proteins, which were previously shown to interact with one another (6, 10), and IcmR was shown to function as a chaperone of IcmQ, thus regulating its pore-forming activity (10, 11). In addition, it was shown before that in various Legionella species, in the exact genomic location of the icmR gene, which is immediately upstream from the icmQ gene and downstream from the icmS gene, completely different genes were found. These highly variable (in sequence and length) genes were named fir genes and, although different in sequence, were found to encode proteins that function similarly to the corresponding IcmQ proteins, with which they were also shown to interact (12, 13). These findings, together with additional information, led to the hypothesis that the FIR and IcmQ proteins coevolved with one another (13).

The L. pneumophila fir gene (icmR) has been previously shown to be directly regulated by the two-component response regulator CpxR (16). The CpxR response regulator is part of a two-component system which includes its cognate CpxA inner-membrane sensor histidine kinase (9, 38). It has been found that this two-component system is activated in Escherichia coli by periplasmic stress, such as accumulation of misfolded proteins in the bacterial periplasm (37). Although CpxR was found to directly regulate the expression of icmR and to influence the expression of other icm/dot genes (16), the signal that activates the CpxAR two-component system in L. pneumophila is as yet unrevealed. In addition, the consensus regulatory element of CpxR was found to be slightly different in Legionella than in other bacteria; in E. coli, the CpxR binding site was shown to be GTAAAnnnnnGTAAA (8), whereas in Legionella species, it was shown to be GTAAAnnnnnnGAAAG (12). This finding correlates with previous evidence that E. coli CpxR does not recognize the L. pneumophila icmR regulatory region (16). The CpxR response regulator has been shown to belong to the OmpR winged helix-turn-helix protein family, the members of which all contain a characteristic helix before the wing domain, which serves as the DNA binding motif (1). Another response regulator that belongs to the same family is the PmrA response regulator, which is a part of the PmrAB two-component system. The PmrAB system has also been found to be present in different pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (18), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (32), Erwinia carotovora (23), and E. coli (19). This system was shown in S. enterica to be responsible for the induction of genes that encode enzymes that are involved in modification of bacterial lipopolysaccharide as a response to specific cues from the environment, such as extracytoplasmic Fe3+ and low pH, thus gaining resistance to host antimicrobial peptides (50). Although the CpxR and PmrA regulators have characteristics in common and were both found to regulate the expression of genes involved in pathogenesis, they were never shown to directly regulate the expression of the same gene.

In the presented study we show, by using bioinformatic, genetic, and biochemical tools, evidence that the CpxR and/or the PmrA response regulators directly bind to the regulatory region of the fir genes and positively regulate their expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

The L. pneumophila strains used in this study were L. pneumophila JR32, a streptomycin-resistant, restriction-negative mutant of L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1, which is a wild-type strain in terms of intracellular growth (43); OG2002, a cpxR mutant (16); HK-PQ1, a pmrA mutant (57); and EA-CRPA, a cpxR pmrA double mutant (this study). Additional Legionella species used in this study were L. erythra ATCC 35303, L. feeleii ATCC 35849, L. longbeachae ATCC 33462, L. micdadei ATCC 33218, and L. rubrilucens ATCC 35304. The E. coli strains used were MC1022, MC1061 (3), and BL21 (Novagen). Bacterial media, plates, and antibiotic concentrations were used as described previously (47). For the plasmids and primers used in this study, see Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material, respectively.

Low-stringency Southern hybridizations.

The genomic DNAs of the six Legionella species indicated above were extracted, digested with EcoRI, and separated by gel electrophoresis. The gel was then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and fixed with a UV cross-linker. Two such membranes were hybridized, one with a cpxR probe and the second with a pmrA probe. Both probes were prepared by PCR amplification of the L. pneumophila genome with the cpxR-pET-F and cpxR-pET-R primers for the cpxR probe and the PmrA-F and PmrA-R primers for the pmrA probe (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The resulting fragments were then labeled with [α-32P]dCTP and used for low-stringency hybridization with 20% formamide as previously described (46).

Cloning of the L. micdadei and L. feeleii cpxR and pmrA genes.

The cpxR and pmrA genes from L. pneumophila were amplified by PCR (with the same primers mentioned above), and the DNA fragments were used as probes for low-stringency hybridization with genomic DNA of L. micdadei and L. feeleii that was digested with XbaI and PstI, respectively. Fragments of approximately 4 kb were then cloned into pUC-18 digested appropriately. Two hundred colonies from each ligation were stabbed onto a new plate, and these colonies were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, which was positioned on a new plate and grown overnight. The colonies grown on the membrane were carefully lysed as previously described (46), and the membranes were used for low-stringency hybridization with the L. pneumophila cpxR or pmrA probe as mentioned above. Positive colonies were picked from the original plate, and the plasmids were extracted from them and sequenced. The pMF-mic21-cpxR and pMF-mic39-pmrA plasmids contained the L. micdadei cpxR (GenBank accession number EF094475) and pmrA (GenBank accession number EF094474) genes, respectively. The pMF-feel67-cpxR and pMF-feel43-pmrA plasmids contained the L. feeleii cpxR (GenBank accession number EF094473) and pmrA (GenBank accession number EF094472) genes, respectively (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Purification of six-His-tagged proteins.

The L. micdadei and L. feeleii CpxR and PmrA proteins were fused to a six-histidine tag at their N termini by PCR amplification with the primers mic-CpxR-His-Nde and mic-CpxR-His-Bam for L. micdadei CpxR, mic-PmrA-His-Nde and mic-PmrA-His-Bam for L. micdadei PmrA, feel-CpxR-His-Nde and feel-CpxR-His-Bam for L. feeleii CpxR, and feel-PmrA-His-Nde and feel-PmrA-His-Bam for L. feeleii PmrA (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The PCR products were then digested with BamHI and NdeI and cloned into the pET-15b vector to generate the pMF-mic-His-cpxR, pMF-mic-His-pmrA, pMF-feel-His-cpxR, and pMF-feel-His-pmrA plasmids (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). All four proteins were purified from E. coli BL21 containing the pRep4 plasmid with nickel bead columns (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After purification, the fractions containing the protein were dialyzed against a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 50 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, and 20% glycerol for 2 h and with the same buffer containing 30% glycerol overnight. The proteins were then stored at −20°C.

Gel mobility shift assays.

Gel mobility shift assays were performed as previously described (20), with few modifications. The regulatory regions of the migB and figA genes, with or without the substitutions (∼180 bp), were amplified by PCR with the primers migB-Eco and migB-Bam for the migB gene and the primers figA-Eco and figA-Bam for the figA gene (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) and 3′ end labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) by using DIG-11-ddUTP (Roche). Increasing amounts of the purified proteins were mixed with 150 pg of the migB-labeled probe or 30 pg of the figA-labeled probe in buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 1 μg/ml poly(dI-dC), 5% glycerol, and 10 ng/ml herring sperm DNA. For samples containing unlabeled probe, 200 ng of the probe was allowed to bind the appropriate protein for 15 min before the addition of the DIG-labeled probe. A binding reaction was carried out for 30 min at room temperature, and samples were then loaded onto 6% polyacrylamide-0.25× Tris-acetate-EDTA gels in 0.5× Tris-acetate-EDTA running buffer. Following electrophoresis, the gels were transferred to nylon membranes and fixed by UV cross-linking. Detection of the DIG-labeled DNA fragments was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Construction of lacZ translational fusions.

To generate the migB::lacZ and figA::lacZ translational fusions, the regulatory regions of the migB and figA genes were amplified by PCR with the primers migB-Eco and migB-Bam for the migB gene and the primers figA-Eco and figA-Bam for the figA gene (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The PCR products were then digested with BamHI and EcoRI, cloned into pGS-lac-02, and sequenced to generate the pMF-migB::lacZ and pMF-figA::lacZ plasmids, respectively (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The levels of expression from these plasmids were measured by a β-galactosidase assay as described below.

Construction of substitutions in the CpxR and PmrA binding sites.

To generate substitutions in the CpxR and PmrA binding sites in the migB and figA regulatory regions, site-directed mutagenesis was performed on the consensus sequences by the PCR overlap extension approach (21). The upstream part of the CpxR binding site was changed from GTAAA to AGCCC, the upstream part of the PmrA binding site was changed from CTTAAG into CGGCCA, or both sequences were mutated simultaneously in the regulatory region of the migB gene. The primers used for the mutagenesis were migB-cpx-mut-F and migB-cpx-mut-R for the mutagenesis of the CpxR site of migB, migB-pmrA-mut-F and migB-pmrA-mut-R for the mutagenesis of the PmrA site of migB, figA-cpx-mut-F and figA-cpx-mut-R for the mutagenesis of the CpxR site of figA, and figA-pmrA-mut-F and figA-pmrA-mut-R for the mutagenesis of the PmrA site of figA (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The resulting fragments were digested with BamHI and EcoRI, cloned into pGS-lac-02, and sequenced, resulting in the pMF-MB-cpxR-mut, pMF-MB-pmrA-mut, and pMF-MB-cpxR-pmrA-mut plasmids containing the substitutions in the migB regulatory region and plasmids pMF-FA-cpxR-mut and pMF-FA-pmrA-mut containing the substitutions in the figA regulatory region (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The plasmids containing the substitutions in the migB regulatory region were introduced into L. micdadei by electroporation with the setup used for L. pneumophila electroporation, and their levels of expression were determined. The plasmids containing the substitutions in the figA regulatory region were used for cloning the L. feeleii cpxR or pmrA gene under the control of the Ptac promoter as described below.

Construction of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible cpxR and pmrA.

The L. feeleii cpxR and pmrA genes were amplified by PCR with the primers feel-CpxR-EcoRI and feel-CpxR-His-Bam for the cpxR gene and feel-PmrA-EcoRI and feel-PmrA-His-Bam for the pmrA gene (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The PCR products were then digested with EcoRI and BamHI and cloned into pMMB207 downstream from the Ptac promoter to generate the pMF-feel-cpxR-207 and pMF-feel-pmrA-207 plasmids. The resulting plasmids were then digested with XbaI and EheI, and the resulting fragments, containing the Ptac-cpxR or Ptac-pmrA gene together with the lacI gene, were cloned into the plasmid containing the regulatory region of the figA gene, as well as the plasmids containing the mutations in the CpxR or PmrA binding site described above, that were digested with XbaI and XmnI, to generate the pMF-FAC, pMF-FAP, pMF-CDC, pMF-CDP, pMF-PDC, and pMF-PDP plasmids (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Construction of the L. pneumophila cpxR pmrA double mutant.

To generate an L. pneumophila cpxR pmrA double-mutant strain, the gentamicin resistance cassette digested with EcoRV was cloned into pOG-cpxR-1 digested with EcoRV to generate pEA-cpxR-Gm, containing an insertion in the cpxR gene, which was then digested with SmaI and cloned into pLAW344 (54) digested with EcoRV to generate pEA-cpxR-Gm-GR. This plasmid was used for an allelic-exchange procedure starting with the L. pneumophila pmrA mutant HK-PQ1 (57) as previously described (48).

β-Galactosidase assay.

A β-galactosidase assay was used to measure the levels of expression of the lacZ translational fusions. β-Galactosidase assays for E. coli strain MC1061 and L. pneumophila strains were performed as previously described (17). To carry out this experiment with L. micdadei, bacteria were grown on charcoal-yeast extract plates for 36 h (exponential phase) or 72 h (stationary phase) and scraped from the plates directly into AC buffer, pH 6.5 [4 mM MgSO4, 0.4 mM CaCl2, 3.4 mM Na-citrate, 0.05 mM Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2, 2.5 mM Na2HPO4, 2.5 mM KH2PO4], and this suspension was used for the β-galactosidase assay as previously described (17).

RESULTS

The fir genes contain similar regulatory elements.

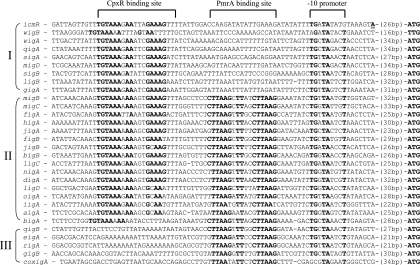

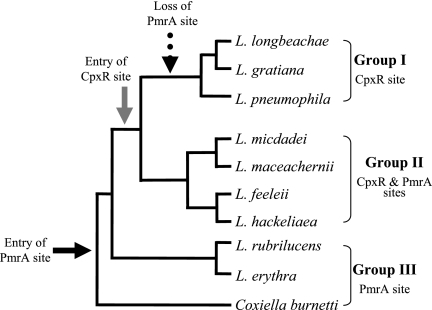

It has been previously found that the expression of the L. pneumophila icmR gene is regulated by the response regulator CpxR (16), and we were interested in examining whether the rest of the fir genes contain the CpxR consensus binding site in the regulatory region. We aligned the regulatory regions of all the fir genes available (Fig. 1). The CpxR binding site was found to be present in most sequences and to be highly conserved. However, to our surprise, the alignment revealed that many of the fir genes contained an additional putative regulatory element located between the −10 promoter and the CpxR binding site (Fig. 1). The L. pneumophila CpxR binding site was shown before to be similar to the E. coli recognition site (Fig. 2A), and a literature search revealed that the new putative regulatory element is highly similar to a sequence known as the consensus binding site of the PmrA response regulator (Fig. 2B), which is known to be part of the PmrAB two-component system (29). The PmrAB two-component system was identified first in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium as required for resistance of the bacteria to antimicrobial peptides such as polymyxin B (41), and since then, it has been shown in other pathogenic bacteria, such as P. aeruginosa (32), E. carotovora (23), and E. coli (19) to be involved in the regulation of genes that are related to virulence. The alignment of the regulatory regions shown in Fig. 1 enabled us to divide the Legionella fir genes into three groups, i.e., (i) genes that contain only the CpxR binding site, (ii) genes that contain both sites, and (iii) genes that contain only the suspected PmrA binding site. Most fir genes were found to belong to the second group (Fig. 1). When a phylogenetic tree was generated from the IcmQ protein sequences (which resulted in the same phylogenetic tree as was published before for the mip gene) (39) for a few representatives from each group (Fig. 3), it was clear that the evolutionary events that led to the generation of the three “fir regulatory groups” perfectly correlate with it. The phylogenetic tree shown in Fig. 3 indicated that the suspected PmrA binding site entered prior to the entry of the CpxR binding site (it is present also in the Coxiella burnetii fir homologue coxigA), and the disappearance of the PmrA binding site is probably an event that occurred later during the course of evolution.

FIG. 1.

Thirty fir genes contain the CpxR and/or the PmrA regulatory element. The regulatory sequences of the fir genes from 29 Legionella species and C. burnetii were aligned. The name of the fir gene is indicated to the left of each sequence. The regulatory elements are in bold, and the regulator that recognizes each motif is indicated above. The −10 promoter is indicated according to the transcription start site that was previously found for the icmR gene, which is in bold and underlined (16). The regulatory regions are divided into three groups (indicated on the left) according to the presence or absence of the regulatory elements, and the distances from the first ATG are indicated. The names of the Legionella species from which the fir genes were aligned (and their accession numbers), from the top, are L. pneumophila (icmR, Y12705), L. waltersii (wigB, AY860648), L. worsleiensis (wigA, AY860646), L. quateirensis (qigA, AY860645), L. shakespearei (sigA, AY860647), L. moravica (migD, AY860644), L. spiritensis (sigB, AY860657), L. longbeachae (ligB, AY512558), L. gratiana (gigA, AY860642), L. micdadei (migB, AY512559), L. maceachernii (migC, AY860654), L. feeleii (figA, AY753535), L. hackeliae (higA, AY753534), L. jamestowniensis (jigA, AY860649), L. fairfieldensis (figB, AY860653), L. jordanis (jigB, AY860651), L. brunensis (bigB, AY860650), L. lansingensis (ligC, AY860652), L. nautarum (nigA, AY860655), L. drozanskii (digA, AY860662), L. londiniensis (ligD, AY860660), L. oakridgensis (oigA, AY860643), L. israelensis (iigA, AY860663), L. adelaidensis (aigA, AY860661), L. birminghamensis (bigA, AY860641), L. quinlivanii (qigB, AY860656), L. erythra (eigA, AY860658), L. rubrilucens (rigA, AY860659), and L. geestiana (gigB, AY860664). coxigA is the fir gene of C. burnetii.

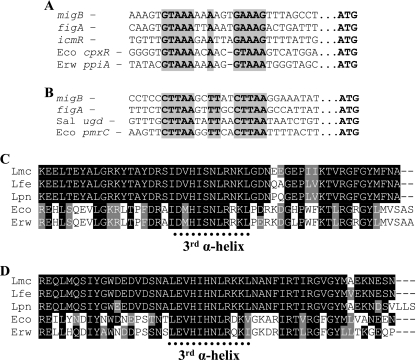

FIG. 2.

The CpxR and PmrA proteins and their binding sites are highly conserved. The regulatory regions of the migB and figA genes were aligned with other regulatory sequences which are known to be regulated by CpxR (A) or PmrA (B) in other bacteria. The names of the bacteria and genes are indicated to the left of each sequence. Abbreviations: Eco, E. coli; Erw, E. carotovora; Sal, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. The CpxR and PmrA consensus sequences are in bold and surrounded by gray. Sequence alignment of the C-terminal ends of the CpxR (C) and PmrA (D) proteins from different bacteria. Abbreviations: Lmc, L. micdadei; Lfe, L. feeleii; Lpn, L. pneumophila; Eco, E. coli; Erw, E. carotovora. The location of the third α-helix sequence of these proteins is indicated at the bottom of each alignment. The third α-helix was predicted by the PSIPRED program (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred). Accession numbers of the migB, figA, and icmR regulatory regions are as listed in the legend to Fig. 1. The rest of the accession numbers are as follows: E. coli cpxR and pmrC genes, NC000913; E. carotovora ppiA gene, NC004547; S. enterica ugd gene, NC003198. Accession numbers of the CpxR proteins: L. micdadei, EF094475; L. feeleii, EF094473; L. pneumophila, AAQ18123; E. coli, NP418348; E. carotovora, YP052398. Accession numbers of the PmrA proteins: L. micdadei, EF094474; L. feeleii, EF094472; L. pneumophila, AAU27375; E. coli, AAV92780; E. carotovora, YP052131.

FIG. 3.

The presence of the CpxR and PmrA binding sites is correlated with the evolutionary tree of the different Legionella species. A rectangular cladogram generated by the sequences of IcmQ proteins from nine Legionella species (accession numbers are the same as those listed for the fir genes in the legend to Fig. 1) and C. burnetii as an outgroup by the ClustalW program with the SRS server (http://srs.ebi.ac.uk/srsbin/cgi-bin/). The nine Legionella species chosen for this analysis are representatives of the three regulatory groups indicated on the right.

The CpxR and PmrA proteins from L. micdadei and L. feeleii are highly conserved.

For further analysis, we chose to continue with L. micdadei and L. feeleii. L. micdadei is known as the second most common Legionnaires’ disease agent in the world (2), and it was found to be less virulent than L. pneumophila in guinea pig and tissue culture models of infection (14, 53). It has been reported that L. micdadei does not inhibit phagosome-lysosome fusion and does not multiply within a ribosome-studded phagosome (26, 40, 53). L. feeleii, on the other hand, was never a subject of any kind of genetic research; however, it was shown to cause very few cases of Legionnaires’ disease (55). The L. micdadei migB and L. feeleii figA genes were chosen to be investigated since they belong to the second group of fir genes containing both regulatory elements. The existence of a CpxR binding site and a PmrA putative binding site in the same regulatory region represents a new type of regulation which has not been described before that occurs in the largest group of fir genes. CpxR and PmrA are both members of the OmpR family of response regulators which contain a winged helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif (1, 30, 31), and their third α-helix was shown to be involved in DNA binding and is highly conserved (5). To determine whether both CpxR and PmrA are directly involved in the regulation of the fir genes, we used low-stringency Southern hybridization with the L. pneumophila cpxR and pmrA genes as probes (in L. pneumophila, Lpg1292 was identified as the pmrA gene by a BLAST search) to clone the L. micdadei and L. feeleii cpxR and pmrA genes. As expected, the third α-helix was found to be highly conserved among the CpxR and PmrA proteins from L. micdadei, L. feeleii, and L. pneumophila, as well as E. coli and E. carotovora (Fig. 2C and D, respectively), strongly indicating that the expected target regulatory elements of these proteins in L. micdadei and L. feeleii will be similar to those of the other bacteria. When we compared the full-length CpxR and PmrA proteins, we found 41 to 50% identity between the Legionella proteins and those of E. coli and E. carotovora, while the identity of the third α-helix of the two proteins among the different bacteria was found to be 82% (Fig. 2C and D). This information, together with the fact that the cpxR and pmrA homologous genes from both Legionella species were found to be located upstream from cpxA and pmrB homologues, respectively (data not shown), strongly indicates that the genes identified are indeed the Legionella homologues of the CpxR and PmrA response regulators. It is interesting that the conservation of the third α-helix of the different PmrA proteins was found to be higher than among the different CpxR proteins, which were found to be highly conserved among the Legionella species but slightly different in comparison to E. coli and E. carotovora CpxR. This observation fits the differences found in the CpxR binding element in the Legionella species in comparison to the E. coli and E. carotovora genes (Fig. 2A) and might explain the inability of the E. coli CpxR response regulator to activate the expression of the L. pneumophila icmR gene (14).

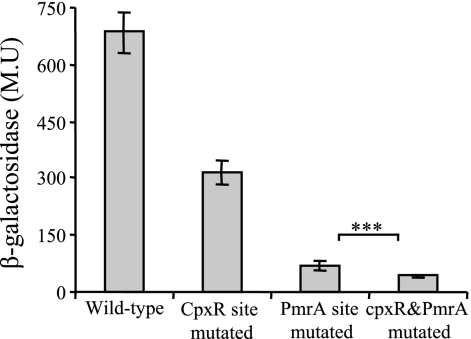

The CpxR and PmrA binding sites are significant for the expression of the L. micdadei migB gene.

To examine whether CpxR and PmrA are involved in the regulation of the migB gene, we constructed a migB::lacZ fusion and three additional plasmids based on it, containing substitutions in the CpxR binding site or the putative PmrA binding site or in both of these sites together. The four resulting plasmids were introduced into L. micdadei, and the level of expression of the migB gene was determined by β-galactosidase assay as described in Materials and Methods. The results obtained showed that the mutations in the CpxR binding site decreased the expression of the migB gene to approximately half of the wild-type levels (Fig. 4). The mutation in the putative PmrA binding site was found to influence the expression of migB even more severely, while the combined mutation lowered the expression to nearly zero levels (Fig. 4). These results point out the relevance of these two regulatory elements for the regulation of the migB gene.

FIG. 4.

The L. micdadei CpxR and PmrA binding sites are required for expression of migB. Plasmids containing the migB::lacZ (wild-type or mutated CpxR and/or PmrA binding sites) were introduced into L. micdadei, and their expression was measured at exponential phase by the β-galactosidase assay as described in Materials and Methods. The results (in Miller units [M.U.]) are the averages ± standard deviations of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed with the standard t test. ***, P < 0.0001.

L. pneumophila CpxR and PmrA regulate the expression of the migB and figA genes.

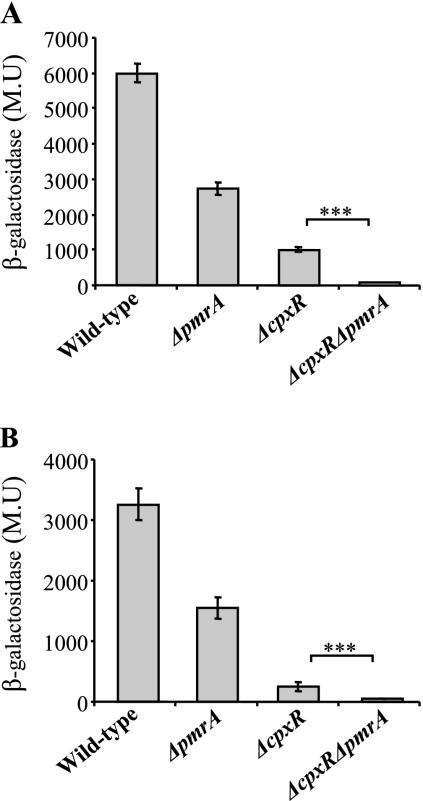

To find out whether the L. micdadei migB gene is indeed regulated by the CpxR and PmrA proteins, we introduced the plasmid containing the migB::lacZ fusion into L. pneumophila containing insertions in the cpxR and/or the pmrA genes. The level of expression of the migB gene was drastically lowered in each of the single-mutant strains, whereas in the double-mutant strain, the expression was more severely lowered (Fig. 5A). Similar results were obtained for the figA::lacZ fusion in the same four L. pneumophila strains (Fig. 5B), indicating that the expression of the migB and figA genes is regulated by the CpxR and PmrA response regulators in an additive manner.

FIG. 5.

The L. pneumophila CpxR and PmrA proteins regulate the expression of the migB and figA genes. Plasmids containing the migB::lacZ (A) or the figA::lacZ (B) fusion were introduced into four L. pneumophila strains, i.e., JR32 (wild type), pmrA mutant strain HK-PQ1 (ΔpmrA), cpxR mutant strain OG2002 (ΔcpxR), and cpxR pmrA double-mutant strain EA-CRPA (ΔcpxR ΔpmrA). Expression was measured at stationary phase by β-galactosidase assay. The results (in Miller units [M.U.]) are the averages ± standard deviations of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed with the standard t test. ***, P < 0.0001.

The L. feeleii CpxR and PmrA proteins are direct regulators of the figA gene.

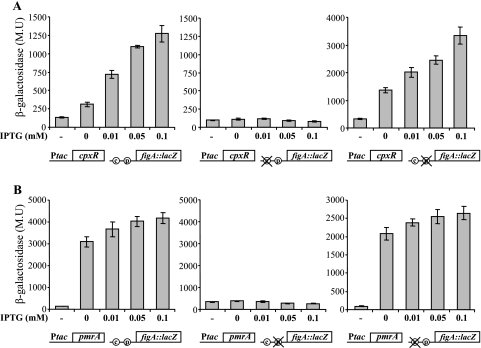

To find out whether the CpxR and PmrA response regulators directly influence the expression of the fir genes examined and if they function independently, we used the L. feeleii figA::lacZ fusion and constructed two additional plasmids containing substitutions in the CpxR or the PmrA binding sites in a way similar to what was described for migB. We then cloned into these three plasmids the L. feeleii cpxR or pmrA gene under the control of the Ptac promoter (induced by IPTG). The resulting plasmids were introduced into E. coli MC1061, and the expression of the figA gene with or without the mutations at the two regulatory elements was determined with different concentrations of IPTG in such a way that in each experiment a single plasmid containing one regulatory sequence and one regulator under the control of the Ptac promoter was examined. The results in Fig. 6 show that L. feeleii CpxR positively regulates the figA gene only when its binding site is intact, and the activation increased as the concentration of IPTG added increased, indicating direct regulation by the CpxR response regulator. Moreover, the figA::lacZ fusion that contained the substitution in the CpxR site was not influenced at all by the addition of IPTG (Fig. 6A). Similar results were obtained with L. feeleii PmrA, but in this case the presence of the pmrA gene on the same plasmid with the figA::lacZ fusion without the addition of IPTG drastically increased the expression of figA (Fig. 6B). This result probably occurred because of the leakiness of the Ptac promoter but strongly indicates that low levels of the PmrA regulator were sufficient for the activation of the figA gene (a result that fits the strong effect obtained with the mutation of the PmrA site in the migB gene [Fig. 4]). As expected, the figA::lacZ fusion containing the substitution in the PmrA binding site was not affected by the addition of IPTG (Fig. 6B). Reciprocal experiments showed that the expression of the figA::lacZ fusion containing a mutation in the PmrA binding site was activated by the CpxR protein (Fig. 6A), and similarly, the figA::lacZ fusion containing a mutated CpxR binding site was activated by the PmrA protein (Fig. 6B). These results show that each of the regulators activates the expression of the figA gene independently, even if the site of the second regulator is missing. The results presented strongly relate the two response regulators with their binding sites and show that they both positively regulate the expression of the same gene directly and independently.

FIG. 6.

The L. feeleii CpxR and PmrA proteins are direct positive regulators of the figA gene. Plasmids containing the figA::lacZ fusion (wild-type or mutated CpxR or PmrA binding sites, as indicated in the schemes below the bars as follows: c, CpxR binding site; p, PmrA binding site; X, mutated site) and the L. feeleii cpxR (A) or pmrA (B) gene under the control of the Ptac promoter (as indicated in the schemes below the bars) were examined in E. coli MC1061. Levels of expression of the different plasmids were measured at different IPTG concentrations (indicated below the bars) by the β-galactosidase assay at exponential phase. The scales of the two graphs on the right are different because of the differences in the initial levels of expression of the mutated fusions examined. As negative controls (indicated by a minus sign), the plasmids containing the figA::lacZ fusion (with or without the mutations) without the cpxR (A) or the pmrA (B) gene were used. The results (in Miller units [M.U.]) are the averages ± standard deviations of at least three independent experiments.

The CpxR and PmrA proteins bind directly to the migB and figA regulatory regions.

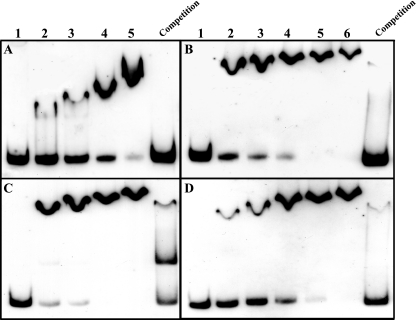

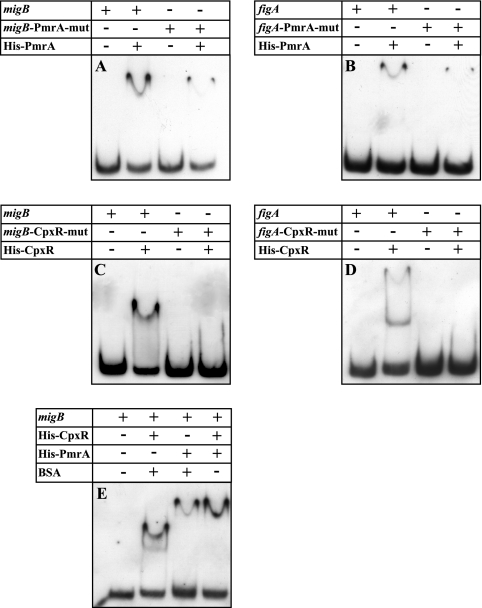

After showing that the CpxR and PmrA response regulators positively regulate the migB and figA genes, we wanted to prove the direct binding between the proteins and the regulatory regions. To do that, we purified the L. micdadei and L. feeleii CpxR and PmrA proteins, tagged all four of them with an N-terminal six-histidine tag, and performed gel mobility shift assays with the purified proteins in increasing amounts and the migB or figA regulatory region labeled with DIG-11-ddUTP. The results of these experiments showed direct binding of the L. micdadei CpxR (Fig. 7A) and PmrA (Fig. 7B) proteins to the migB regulatory region and of the L. feeleii CpxR (Fig. 7C) and PmrA (Fig. 7D) proteins to the figA regulatory region. To examine whether this binding was specific, we added unlabeled probe to the binding reaction mixture and found that the unlabeled probes competed with the labeled probes for association with the relevant protein (Fig. 7). To further investigate the association of these regulators with their target sequences, we examined the PmrA (Fig. 8A and B) and CpxR (Fig. 8C and D) proteins for binding to the mutated migB and figA regulatory regions. Binding of the PmrA protein to the migB (Fig. 8A) and figA (Fig. 8B) regulatory regions that contained a mutation in the PmrA binding site was significantly reduced. In addition, the CpxR regulator did not bind at all to the migB (Fig. 8C) and figA (Fig. 8D) regulatory regions which contained a mutation in the CpxR binding site. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 8E, the CpxR and PmrA regulators were able to bind simultaneously to the same regulatory region, as indicated by a shift that is stronger than the one observed for each of the proteins by itself. The results obtained by the different gel mobility shift assays prove that binding of these two response regulators to their target sequences is direct, specific, and independent.

FIG. 7.

The L. micdadei and L. feeleii CpxR and PmrA proteins bind the regulatory regions of the migB and figA genes. Mobility shift assays were performed with the L. micdadei pure His6-CpxR (A) and His6-PmrA (B), the L. feeleii pure His6-CpxR (C) and His6-PmrA (D), and the DIG-labeled migB (A and B) and figA (C and D) regulatory regions. The first lane in each gel did not contain any protein. The rest of the numbered lanes contained increasing amounts of the relevant proteins in twofold increments, starting from 0.125 μg (A), 0.25 μg (B), 0.5 μg (C), and 0.25 μg (D). Competition was performed by incubating the protein amount added to the second lane (the smallest amount) with 200 ng of the unlabeled probe as a specific competitor for 15 min prior to the addition of the DIG-labeled probe. The lane numbers and competition in each lane are indicated.

FIG. 8.

Binding of the CpxR and PmrA proteins to their target genes is specific and independent. Binding of the PmrA protein to the migB and figA probes was decreased when the PmrA site was mutated (A and B, respectively), and the CpxR protein did not bind to these probes when the CpxR site was mutated (C and D, respectively). The probe or protein added to each reaction mixture is indicated above each lane. (E) Independence of binding of the CpxR and PmrA proteins was examined by incubating the L. micdadei CpxR and/or PmrA proteins with equal amounts of the migB probe. Bovine serum albumin was added to the reaction mixtures containing the same amounts of individual proteins. The addition of each protein (60 ng) is indicated above each lane.

CpxR and PmrA exist in the genomes of species from the three groups.

As shown in Fig. 1, the L. pneumophila fir gene—icmR—does not contain the PmrA binding site although a PmrA-encoding gene is present in the L. pneumophila genome. Therefore, we were interested in examining whether there is a connection between the presence of the CpxR and/or PmrA binding site in the fir regulatory region and the presence of its corresponding regulator in Legionella species that belong to each of the three fir regulatory groups described above. To find out whether these species contain the coding sequence of the cpxR and pmrA genes, low-stringency Southern hybridizations were performed. The genomic DNAs from two representatives of each of the three groups (group I, L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae, whose fir genes contain only the CpxR binding site; group II, L. micdadei and L. feeleii, whose fir genes contain both regulatory elements; and group III, L. rubrilucens and L. erythra, whose fir genes contain only the PmrA binding site) were hybridized with the cpxR and pmrA genes from L. pneumophila under low-stringency conditions. The hybridizations results showed that all six of the species examined contained both genes (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), indicating that these two response regulators (CpxR and PmrA) might regulate the expression of other genes and that the appearance or loss of the regulatory element from the regulatory region of the different fir genes is not due to the existence or disappearance of the corresponding regulatory protein.

DISCUSSION

L. pneumophila is known to infect and replicate inside human macrophages and amoebae (22) using the Icm/Dot type IV secretion system, which is encoded by 25 genes (44, 45, 51, 52). The IcmR and IcmQ proteins are two components of the Icm/Dot system that were shown to be located in the bacterial cytoplasm (5, 43). IcmQ was shown to consist of pore-forming activity inside lipid membranes by self-interaction, which was found to be regulated by the association of IcmQ with IcmR—its chaperone (11). The genome of C. burnetii, the causative agent of Q fever, was also found to contain a complete Icm/Dot system, except for the icmR gene (56, 58), which was shown to be replaced with a different gene—coxigA—that encodes a protein that was shown to interact with its corresponding IcmQ protein (13). It was previously shown that, similarly to the situation in C. burnetii, several other Legionella species that were found to grow within human macrophages and different types of protozoa and to cause Legionnaires’ disease (15) contain in their genomes completely different genes upstream from a highly conserved icmQ gene. These genes were found to function similarly together with their corresponding icmQ genes (12, 13) and therefore were named fir genes, for functional homologues of icmR (13).

In this study, we examined the regulation of the hypervariable fir genes in order to learn more about the functional similarities between them. Alignment of the regulatory regions of 30 fir genes clearly showed that most of them contain a CpxR binding site, and to our surprise, the alignment revealed an additional element which was identified as the consensus binding sequence of the PmrA response regulator (Fig. 1). The existence of these two binding sites divided the fir genes into three regulatory groups, which contain either one of these binding sites or both of them (there is not even one fir gene that does not contain at least one of these sites). It is interesting that each of the three groups contains at least one Legionella species that was previously isolated from patients, for example, L. pneumophila (group I), L. micdadei (group II), and L. erythra (group III) (15). This information indicates the lack of correlation between the existence of these regulatory elements and the ability of the relevant species to cause pneumonia in humans. In the present study, we chose to further analyze the regulatory regions of L. micdadei migB and L. feeleii figA, both containing both binding sites. We showed that the CpxR and PmrA proteins directly bind to the regulatory sequences of the migB and figA genes and positively regulate their expression.

Regulation of one gene by two different two-component systems could be explained by the necessity of a certain gene to be expressed in response to different signals which activate different two-component systems, and few such cases have been described before. For example, the S. enterica ugd gene is triggered by the PmrAB system, which is activated by a high concentration of extracytoplasmic Fe3+ and also by the RcsCB system that responds to cell envelope stress, thus enabling one gene to be expressed under different stress conditions (33). The expression of the ugd gene was also shown to be elevated in response to low levels of Mg2+, which activate the PhoPQ two-component system, which activates the expression of the PmrD protein that consequently activates the PmrAB system in a posttranscriptional manner and results in up-regulation of the ugd gene (25). The latter is an example of a case in which two response regulators, PhoP and PmrA, which are both members of the winged helix-turn-helix protein family (1) control the expression of a single gene. The regulation of the csgD gene in E. coli by the OmpR and CpxR response regulators upon two distinct signals is another example of the activation of one gene by two members of the winged helix-turn-helix family under different conditions (24).

The CpxR and PmrA response regulators that were shown here to bind the same regulatory regions and activate the same fir genes are both members of the winged helix-turn-helix protein family (1), but they have never been shown to directly regulate the expression of the same gene. We show here evidence regarding the evolution of regulatory sequences among a large number of Legionella species regardless of the existence of the corresponding regulators in the bacteria, an evolution which might have occurred in order to allow optimal adaptation of a certain species to its environment. Group I was shown to include Legionella species that contain only the PmrA regulatory element, and since this regulatory element was also found in the regulatory region of the C. burnetii fir gene (which is not part of the genus Legionella), it is most likely that this is an ancestral regulatory element. At some point during evolution, a second regulatory element was acquired, the CpxR regulatory element, and group II was formed, probably in order to enable the relevant fir genes to be expressed as a response to an additional environmental signal sensed by the cognate sensor kinase CpxA. The disappearance of the ancestral PmrA regulatory element formed the third regulatory group and might have happened since the corresponding species existed in a niche where the expression of the fir genes was no longer required as a response to the signal sensed by the PmrB sensor kinase. However, the fact that the CpxR and PmrA regulators are able to activate the fir genes independently from each other might lead to the hypothesis that each of the three regulatory groups exists in an environment that requires different expression patterns of the relevant fir gene.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Israel Science Foundation (393/03).

We thank Efrat Altman for the construction of the L. pneumophila cpxR pmrA double mutant.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 March 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aravind, L., V. Anantharaman, S. Balaji, M. M. Babu, and L. M. Iyer. 2005. The many faces of the helix-turn-helix domain: transcription regulation and beyond. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:231-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benin, A. L., R. F. Benson, and R. E. Besser. 2002. Trends in Legionnaires’ disease, 1980-1998: declining mortality and new patterns of diagnosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:1039-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casadaban, M. J., and S. N. Cohen. 1980. Analysis of gene control signals by DNA fusion and cloning in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 138:179-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, J., K. S. de Felipe, M. Clarke, H. Lu, O. R. Anderson, G. Segal, and H. A. Shuman. 2004. Legionella effectors that promote nonlytic release from protozoa. Science 303:1358-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, Y., W. R. Abdel-Fattah, and F. M. Hulett. 2004. Residues required for Bacillus subtilis PhoP DNA binding or RNA polymerase interaction: alanine scanning of PhoP effector domain transactivation loop and alpha helix 3. J. Bacteriol. 186:1493-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coers, J., J. C. Kagan, M. Matthews, H. Nagai, D. M. Zuckman, and C. R. Roy. 2000. Identification of Icm protein complexes that play distinct roles in the biogenesis of an organelle permissive for Legionella pneumophila intracellular growth. Mol. Microbiol. 38:719-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conover, G. M., I. Derre, J. P. Vogel, and R. R. Isberg. 2003. The Legionella pneumophila LidA protein: a translocated substrate of the Dot/Icm system associated with maintenance of bacterial integrity. Mol. Microbiol. 48:305-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Wulf, P., A. M. McGuire, X. Liu, and E. C. Lin. 2002. Genome-wide profiling of promoter recognition by the two-component response regulator CpxR-P in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 277:26652-26661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong, J., S. Iuchi, H. S. Kwan, Z. Lu, and E. C. Lin. 1993. The deduced amino-acid sequence of the cloned cpxR gene suggests the protein is the cognate regulator for the membrane sensor, CpxA, in a two-component signal transduction system of Escherichia coli. Gene 136:227-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duménil, G., and R. R. Isberg. 2001. The Legionella pneumophila IcmR protein exhibits chaperone activity for IcmQ by preventing its participation in high-molecular-weight complexes. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1113-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duménil, G., T. P. Montminy, M. Tang, and R. R. Isberg. 2004. IcmR-regulated membrane insertion and efflux by the Legionella pneumophila IcmQ protein. J. Biol. Chem. 279:4686-4695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman, M., and G. Segal. 2004. A specific genomic location within the icm/dot pathogenesis region of different Legionella species encodes functionally similar but nonhomologous virulence proteins. Infect. Immun. 72:4503-4511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldman, M., T. Zusman, S. Hagag, and G. Segal. 2005. Coevolution between nonhomologous but functionally similar proteins and their conserved partners in the Legionella pathogenesis system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:12206-12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fields, B. S., J. M. Barbaree, E. B. Shotts, Jr., J. C. Feeley, W. E. Morrill, G. N. Sanden, and M. J. Dykstra. 1986. Comparison of guinea pig and protozoan models for determining virulence of Legionella species. Infect. Immun. 53:553-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fields, B. S., R. F. Benson, and R. E. Besser. 2002. Legionella and Legionnaires’ disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:506-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gal-Mor, O., and G. Segal. 2003. Identification of CpxR as a positive regulator of icm and dot virulence genes of Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 185:4908-4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gal-Mor, O., T. Zusman, and G. Segal. 2002. Analysis of DNA regulatory elements required for expression of the Legionella pneumophila icm and dot virulence genes. J. Bacteriol. 184:3823-3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groisman, E. A. 2001. The pleiotropic two-component regulatory system PhoP-PhoQ. J. Bacteriol. 183:1835-1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagiwara, D., T. Yamashino, and T. Mizuno. 2004. A genome-wide view of the Escherichia coli BasS-BasR two-component system implicated in iron-responses. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 68:1758-1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haydel, S. E., W. H. Benjamin, Jr., N. E. Dunlap, and J. E. Clark-Curtiss. 2002. Expression, autoregulation, and DNA binding properties of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis TrcR response regulator. J. Bacteriol. 184:2192-2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho, S. N., H. D. Hunt, R. M. Horton, J. K. Pullen, and L. R. Pease. 1989. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77:51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horwitz, M. A. 1983. The Legionnaires’ disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) inhibits phagosome-lysosome fusion in human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 158:2108-2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyytiäinen, H., S. Sjoblom, T. Palomaki, A. Tuikkala, and E. Tapio Palva. 2003. The PmrA-PmrB two-component system responding to acidic pH and iron controls virulence in the plant pathogen Erwinia carotovora ssp. carotovora. Mol. Microbiol. 50:795-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jubelin, G., A. Vianney, C. Beloin, J. M. Ghigo, J. C. Lazzaroni, P. Lejeune, and C. Dorel. 2005. CpxR/OmpR interplay regulates curli gene expression in response to osmolarity in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187:2038-2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kox, L. F., M. M. Wosten, and E. A. Groisman. 2000. A small protein that mediates the activation of a two-component system by another two-component system. EMBO J. 19:1861-1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levi, M. H., A. W. Pasculle, and J. N. Dowling. 1987. Role of the alveolar macrophage in host defense and immunity to Legionella micdadei pneumonia in the guinea pig. Microb. Pathog. 2:269-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luo, Z. Q., and R. R. Isberg. 2004. Multiple substrates of the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system identified by interbacterial protein transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:841-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Machner, M. P., and R. R. Isberg. 2006. Targeting of host Rab GTPase function by the intravacuolar pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Dev. Cell 11:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchal, K., S. De Keersmaecker, P. Monsieurs, N. van Boxel, K. Lemmens, G. Thijs, J. Vanderleyden, and B. De Moor. 2004. In silico identification and experimental validation of PmrAB targets in Salmonella typhimurium by regulatory motif detection. Genome Biol. 5:R9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martínez-Hackert, E., and A. M. Stock. 1997. The DNA-binding domain of OmpR: crystal structures of a winged helix transcription factor. Structure 5:109-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martínez-Hackert, E., and A. M. Stock. 1997. Structural relationships in the OmpR family of winged-helix transcription factors. J. Mol. Biol. 269:301-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McPhee, J. B., S. Lewenza, and R. E. Hancock. 2003. Cationic antimicrobial peptides activate a two-component regulatory system, PmrA-PmrB, that regulates resistance to polymyxin B and cationic antimicrobial peptides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 50:205-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mouslim, C., and E. A. Groisman. 2003. Control of the Salmonella ugd gene by three two-component regulatory systems. Mol. Microbiol. 47:335-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murata, T., A. Delprato, A. Ingmundson, D. K. Toomre, D. G. Lambright, and C. R. Roy. 2006. The Legionella pneumophila effector protein DrrA is a Rab1 guanine nucleotide-exchange factor. Nat. Cell Biol. 8:971-977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagai, H., J. C. Kagan, X. Zhu, R. A. Kahn, and C. R. Roy. 2002. A bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factor activates ARF on Legionella phagosomes. Science 295:679-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ninio, S., D. M. Zuckman-Cholon, E. D. Cambronne, and C. R. Roy. 2005. The Legionella IcmS-IcmW protein complex is important for Dot/Icm-mediated protein translocation. Mol. Microbiol. 55:912-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raivio, T. L., and T. J. Silhavy. 2001. Periplasmic stress and ECF sigma factors. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:591-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raivio, T. L., and T. J. Silhavy. 1997. Transduction of envelope stress in Escherichia coli by the Cpx two-component system. J. Bacteriol. 179:7724-7733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ratcliff, R. M., J. A. Lanser, P. A. Manning, and M. W. Heuzenroesder. 1998. Sequence-based classification scheme for the genus Legionella targeting the mip gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1560-1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rechnitzer, C., and J. Blom. 1989. Engulfment of the Philadelphia strain of Legionella pneumophila within pseudopod coils in human phagocytes. Comparison with other Legionella strains and species. APMIS 97:105-114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roland, K. L., L. E. Martin, C. R. Esther, and J. K. Spitznagel. 1993. Spontaneous pmrA mutants of Salmonella typhimurium LT2 define a new two-component regulatory system with a possible role in virulence. J. Bacteriol. 175:4154-4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rowbotham, T. J. 1980. Preliminary report on the pathogenicity of Legionella pneumophila for freshwater and soil amoebae. J. Clin. Pathol. 33:1179-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sadosky, A. B., L. A. Wiater, and H. A. Shuman. 1993. Identification of Legionella pneumophila genes required for growth within and killing of human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 61:5361-5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Segal, G., M. Feldman, and T. Zusman. 2005. The Icm/Dot type-IV secretion systems of Legionella pneumophila and Coxiella burnetii. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:65-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Segal, G., M. Purcell, and H. A. Shuman. 1998. Host cell killing and bacterial conjugation require overlapping sets of genes within a 22-kb region of the Legionella pneumophila genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1669-1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Segal, G., and E. Z. Ron. 1993. Heat shock transcription of the groESL operon of Agrobacterium tumefaciens may involve a hairpin-loop structure. J. Bacteriol. 175:3083-3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Segal, G., and H. A. Shuman. 1997. Characterization of a new region required for macrophage killing by Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 65:5057-5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segal, G., and H. A. Shuman. 1999. Legionella pneumophila utilize the same genes to multiply within Acanthamoeba castellanii and human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 67:2117-2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shohdy, N., J. A. Efe, S. D. Emr, and H. A. Shuman. 2005. Pathogen effector protein screening in yeast identifies Legionella factors that interfere with membrane trafficking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:4866-4871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamayo, R., A. M. Prouty, and J. S. Gunn. 2005. Identification and functional analysis of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium PmrA-regulated genes. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 43:249-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vincent, C. D., J. R. Friedman, K. C. Jeong, E. C. Buford, J. L. Miller, and J. P. Vogel. 2006. Identification of the core transmembrane complex of the Legionella Dot/Icm type IV secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 62:1278-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vogel, J. P., H. L. Andrews, S. K. Wong, and R. R. Isberg. 1998. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science 279:873-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weinbaum, D. L., R. R. Benner, J. N. Dowling, A. Alpern, A. W. Pasculle, and G. R. Donowitz. 1984. Interaction of Legionella micdadei with human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 46:68-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiater, L. A., A. B. Sadosky, and H. A. Shuman. 1994. Mutagenesis of Legionella pneumophila using Tn903dlllacZ: identification of a growth-phase-regulated pigmentation gene. Mol. Microbiol. 11:641-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu, V. L., J. F. Plouffe, M. C. Pastoris, J. E. Stout, M. Schousboe, A. Widmer, J. Summersgill, T. File, C. M. Heath, D. L. Paterson, and A. Chereshsky. 2002. Distribution of Legionella species and serogroups isolated by culture in patients with sporadic community-acquired legionellosis: an international collaborative survey. J. Infect. Dis. 186:127-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zamboni, D. S., S. McGrath, M. Rabinovitch, and C. R. Roy. 2003. Coxiella burnetii express type IV secretion system proteins that function similarly to components of the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system. Mol. Microbiol. 49:965-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zusman, T., G. Aloni, E. Halperin, H. Kotzer, E. Degtyar, M. Feldman, and G. Segal. 2007. The response regulator PmrA is a major regulator of the icm/dot type-IV secretion system in Legionella pneumophila and Coxiella burnetii. Mol. Microbiol. 63:1508-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zusman, T., G. Yerushalmi, and G. Segal. 2003. Functional similarities between the icm/dot pathogenesis systems of Coxiella burnetii and Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 71:3714-3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.