Abstract

Objective

To examine the potential therapeutic effect of methotrexate 20 mg given weekly as subcutaneous injections to 20 patients with ankylosing spondylitis refractory to non‐steriodal antirheumatic drugs.

Patients and methods

20 patients with ankylosing spondylitis, a mean Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) score of 5.6 (range 4–9.3) and predominantly axial manifestations were treated with weekly 15 mg methotrexate subcutaneously for 4 weeks, which was then increased to 20 mg subcutaneously for the next 12 weeks. Clinical outcome assessments included, among others, BASDAI score physical function, spinal mobility, patients' and physicians' global assessment (visual analogue scale), peripheral joint assessment, quality of life (Short Form 36) and C reactive protein. The primary end point of the study was a 20% improvement on the ASsessments in Ankylosing Spondylitis (ASAS 20) scale.

Results

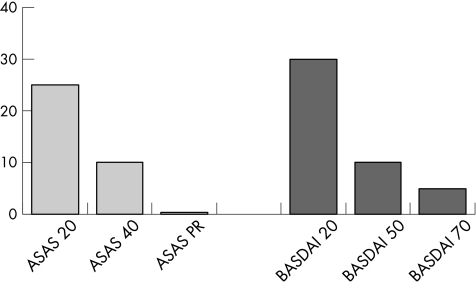

Using an intention‐to‐treat analysis, ASAS 20 was achieved in only 25% of patients. An ASAS 40 response was achieved in 10% of patients, and no patient reached an ASAS 70 response or the ASAS criteria for partial remission. For the mean BASDAI score, no change was observed between baseline and week 16 (baseline 5.6 v week 16, 5.6). No improvement was observed in any of the clinical parameters or C reactive protein, except a small but non‐significant decrease in the number of swollen joints.

Conclusions

In this open study, methotrexate did not show any benefit for axial manifestations in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis beyond the expected placebo response.

Ankylosing spondylitis is a frequent inflammatory rheumatic disease and the prototype of the spondyloarthritides (SpA). It starts mostly in the third decade of life. Until recently, non‐steroidal antirheumatic drugs (NSAIDs) and physical treatment were the only established treatment for ankylosing spondylitis. The tumour necrosis factor (TNF)α blocking agents (eg, infliximab) were recently shown to be highly effective in active ankylosing spondylitis resistant to NSAID treatment.1 However, there is no evidence that disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as methotrexate and sulfasalazine, which have high efficacy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and are regarded as the preferred treatment for active forms of rheumatoid arthritis, have any role in the treatment of the axial manifestations of ankylosing spondylitis. Sulfasalazine has shown to be effective only for the peripheral joint involvement in ankylosing spondylitis and other SpA.2 This is also reflected in the current ASsessments in Ankylosing Spondylitis (ASAS)/European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis.3 Surprisingly, despite the lack of evidence of any efficacy, there are several reports detailing treatment with DMARDS of up to 40% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis preferentially with sulfasalazine and methotrexate,4,5,6 although in most, information about a correlation between DMARD treatment and the presence of concomitant peripheral arthritis was not given.

Methotrexate had been tested to date in three randomised controlled trials with a dosage between 7.5 and 10 mg/week versus placebo, with a treatment duration between 12 and 24 weeks. It was not superior to placebo in two of these studies7,8; only in one study with a high percentage of patients with concurrent peripheral arthritis was a better response in some of the outcome variables found.9 A similar result was obtained in an open study of 34 patients treated with methotrexate given intramuscularly at a dose of 12.5 mg/week.10 However, the dosages tested in these studies were relatively low compared with those currently used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Therefore, it has been argued that the lack of evidence of methotrexate for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis might be due to underdosing.

The aim of our study was to investigate the potential therapeutic effects of 20 mg subcutaneous methotrexate (15 mg in the first 4 weeks) in patients with active NSAID‐refractory ankylosing spondylitis over a total treatment period of 16 weeks using evaluated clinical outcome parameters.

Patients and methods

In this open study, we examined 20 patients (table 1 gives their characteristics) who fulfilled the 1984 modified New York criteria for ankylosing spondylitis and who did not respond sufficiently to NSAID treatment, defined as failure or intolerance to maximum dose of at least one NSAID. To be eligible, patients had to have active disease, defined as a Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) score ⩾4. DMARDs and steroids >7.5 mg/day were not permitted and had to be discontinued at least 1 month before starting treatment. Local ethics committee approval was obtained.

Table 1 Patients' baseline characteristics.

| Mean (SD, range) age (years) | 40 (9.2, 24–59) |

| Mean (SD, range) disease duration (years) | 14 (10.2, 1–39) |

| Sex, male:female (n) | 14:6 |

| HLA‐B27 positivity (%) | 85 |

| Mean (SD, range) BASDAI at screening | 5.6 (1.2, 4–9.3) |

| CRP >10 mg/l at screening (%) | 40 |

| Peripheral arthritis at screening (n) | 7 |

| Enthesitis at screening (Berlin scale) (n) | 8 |

| IBD (history and at screening) (n) | 0 |

| Psoriasis (history and at screening) (n) | 4 |

| History of anterior uveitis (n) | 3 |

| Concomitant treatment at screening | |

| NSAIDs (n) | 20 |

| Glucocorticoids (n) | 4 |

| Previous DMARDs (n) | 6 |

BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CRP, C reactive protein (normal value <5 mg/l); DMARDs, disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; NSAIDs, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs.

Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, history of uncontrolled concomitant diseases, or clinical and laboratory examinations with abnormal or clinically relevant changes.

Methotrexate 15 mg was given subcutaneously every week for 4 weeks, followed, if tolerated, by methotrexate 20 mg subcutaneously every week for a further 12 weeks.

Clinical outcome assessments were performed every month, and included BASDAI score, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index, a spinal pain score performed by the physician, quality of life measurement using the Short Form 36 (SF‐36), patients' and physicians' global assessment (numerical rating scales 0–10), number of swollen joints (64‐joint score) and number of enthesitic sites (Berlin Score).1 The primary outcome parameter was a 20% improvement according to the ASAS criteria (ASAS 20)11 after 16 weeks. Laboratory outcome assessments included erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein. Reduction in NSAID doses were allowed but had to be recorded.

Statistics

Statistics were performed as an intention‐to‐treat, last observation carried forward analysis. The non‐parametric Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare changes between baseline to after‐treatment values; p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

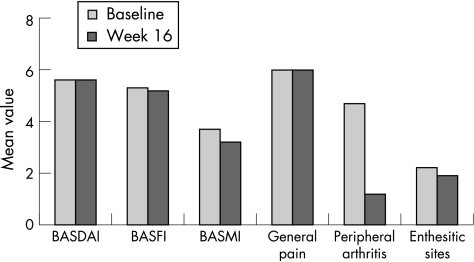

In all, 16 of 20 patients completed the whole study period of 16 weeks. The doses could not be increased from 15 to 20 mg/ week subcutaneously in one patient because of oral mucosal lesions and in two patients because of nausea. Using an intention‐to‐treat, last observation carried forward analysis after 16 weeks for the primary outcome parameter, an ASAS 20 response was achieved in 25% (n = 5) of patients. An ASAS 40 response was achieved in 10% of patients and no patient reached an ASAS 70 response or the ASAS criteria for partial remission (fig 1). Of the 20 patients, 30% achieved BASDAI 20, 10% BASDAI 50 and 5% BASDAI 70 (fig 1). For the mean BASDAI, there was no change between baseline and week 16 (5.6 at baseline v 5.6 at week 16). No single component of the BASDAI improved significantly. There was also no improvement in any other secondary outcome parameter (fig 2), including spinal pain score performed by the physician (not shown) or the value for C reactive protein (1 mg/dl before v 0.8 mg/dl at the end of treatment). When mean BASDAI changes for different subgroups were compared, there were no differences for disease duration, body weight or peripheral arthritis.

Figure 1 ASessments in Ankylosing Spondylitis (ASAS) 20% and 40% response and ASAS criteria for partial remission (PR) and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity (BASDAI) 20%, 50% and 70% improvement in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis after 16 weeks of treatment with methotrexate.

Figure 2 Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI), general pain (numerical rating scale), number of swollen joints (only in patients with peripheral arthritis (n = 7)) and enthesitic sites in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis treated with methotrexate 20 mg over 16 weeks. p>0.05 for all parameters including peripheral arthritis.

There was a small non‐significant decrease in the number of swollen joints in the seven patients who had peripheral arthritis at baseline: the number of swollen joints at baseline decreased from 4.7 to 1.2 at the end of the study (fig 2). No improvement was found for the number of enthesitic sites during the study period (baseline 2.2 v 1.9 at week 16; fig 2).

Side effects

Methotrexate was well tolerated. Nausea (in seven patients) and infections of the upper respiratory tract (in six patients) were the most commonly reported adverse events. The only reported serious adverse event was NSAID‐associated gastrointestinal bleeding.

Dropout rate

Four patients stopped treatment before the end of the trial because of inefficacy, non‐compliance or side effects; two patients after 4 weeks and two patients after 12 weeks of methotrexate treatment.

Discussion

In this open‐label study on patients with active NSAID‐refractory ankylosing spondylitis, 20 mg methotrexate given parenterally—a dose that is close to the upper limit normally used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis—did not show any efficacy as measured by the BASDAI or any other clinical outcome parameter over 16 weeks (fig 1). In two patients who dropped out after 4 weeks, efficacy could not be evaluated.

An ASAS 20 response, the primary outcome parameter in our study, was achieved in 25% of the patients, which is similar to the placebo responses in the TNFα antagonist trials1 and to the placebo response in an NSAID trial with etoricoxib.12 We have also reported earlier that leflunomide,13 a drug that is effective for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, did not show any efficacy in ankylosing spondylitis. The response rate reported in our study with methotrexate was even lower. The mean disease duration was 14 years, similar to other treatment trials1,12,13. Therefore, we cannot exclude a potential effect of methotrexate in patients with ankylosing spondylitis with shorter disease duration.

Interestingly, in the subgroup of seven patients who also had peripheral arthritis, a small but non‐significant improvement in the number of swollen joints was observed, a result in line with previous studies on methotrexate 7,8,9,10 and with our previous report on treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with leflunomide.13 Although such a differential effect on peripheral and axial manifestations of ankylosing spondylitis and other SpA can be considered proven for the treatment with sulfasalazine,2 further studies with methotrexate are needed in SpA, concentrating on patients with predominantly peripheral involvement.

At present, the failure of conventional DMARDs in the treatment of the axial manifestations of ankylosing spondylitis can only be speculated; although synovitis is often, similar to rheumatoid arthritis, the major immunopathological factor in peripheral arthritis, osteitis at the bone–cartilage interphase seems to the predominant immunopathological factor in the spine and pelvis, which could be one of the reasons for this difference.

The high efficacy of a combination of methotrexate with any of the TNF blockers compared with treatment with TNF blockers only has also raised the question of whether methotrexate should be added to TNF blockers for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Furthermore, a study on the treatment of patients with Crohn's disease with infliximab suggested that concomitant treatment with azothioprine, methotrexate or glucocorticoids can prevent the production of anti‐infliximab antibodies and, probably via this mechanism, can increase efficacy and reduce allergic reactions.14 However, to date, there are two treatment studies on ankylosing spondylitis investigating a combination of infliximab with methotrexate,4,15 both of which suggest that a combination is not superior to infliximab alone.

In conclusion, our study showed that high doses of methotrexate given over a period of 4 months is not effective in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis with predominant axial manifestations. Thus, despite current practice, methotrexate should not be used for this indication. The exact role of methotrexate for the treatment of peripheral arthritis in SpA has to be investigated in future studies.

Abbreviations

DMARD - disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug

ASAS - ASsessments in Ankylosing Spondylitis

NSAID - non‐steroidal antirheumatic drug

SpA - spondyloarthritides

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by Medac.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, Zink A, Alten R, Krause A.et al Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab—a double‐blind placebo controlled multicenter trial. Lancet 20023591187–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dougados M, van der Linden S, Leirisalo‐Repo M, Huitfeldt B, Juhlin R, Veys E.et al Sulfasalazine in the treatment of spondyloarthritides. Arthritis Rheum 199538618–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zochling J, van der Heijde D, Burgos‐Vargas R, Collantes E, Davis J C, Jr, Dijkmans B.et al ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 200665442–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breban M, Ravaud P, Claudepierre P, Baron G, Hudry C, Euller‐Ziegler L.et al No superiority of infliximab (INF) + methotrexate (MTX) over INF alone in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis (AS): results of a one‐year randomized prospective study. Arthritis Rheum 200552(Suppl)S214 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heiberg M S, Nordvag B Y, Mikkelsen K, Rodevand E, Kaufmann C, Mowinckel P.et al The comparative effectiveness of tumor necrosis factor‐blocking agents in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a six‐month, longitudinal, observational, multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum 2005522506–2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward M M, Kuzis S. Medication toxicity among patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 200247234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altan L, Bingol U, Karakoc Y, Aydiner S, Yurtkuran M, Yurtkuran M. Clinical investigation of methotrexate in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis [erratum appears in Scand J Rheumatol 2003;32:380]. Scand J Rheumatol 200130255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roychowdhury B, Bintley‐Bagot S, Bulgen D Y, Thompson R N, Tunn E J, Moots R J. Is methotrexate effective in ankylosing spondylitis? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002411330–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez‐Lopez L, Garcia‐Gonzalez A, Vazquez‐Del‐Mercado M, Munoz‐Valle J F, Gamez‐Nava J I. Efficacy of methotrexate in ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. J Rheumatol 2004311568–1574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sampaio‐Barros P D, Costallat L T, Bertolo M B, Neto J F, Samara A M. Methotrexate in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Scand J Rheumatol 200029160–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson J J, Baron G, van der Heijde D, Felson D T, Dougados M. Ankylosing spondylitis assessment group preliminary definition of short‐term improvement in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2001441876–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Heijde D, Baraf H S, Ramos‐Remus C, Calin A, Weaver A L, Schiff M.et al Evaluation of the efficacy of etoricoxib in ankylosing spondylitis: results of a fifty‐two‐week, randomized, controlled study. Arthritis Rheum 2005521205–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haibel H, Rudwaleit M, Braun J, Sieper J. Six months open label trial of leflunomide in active ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 200564124–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, Van Assche G, D'Haens G, Carbonez A.et al Influence of immunogenicity on the long‐term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 2003348601–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marzo‐Ortega H, McGonagle D, Jarrett S, Haugeberg G, Hensor E, O'connor P.et al Infliximab in combination with methotrexate in active ankylosing spondylitis: a clinical and imaging study. Ann Rheum Dis 2005641568–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]