Pandolfino et al (Gut 2005;54:1687–92) and Bruley des Varannes et al (Gut 2005;54:1682–6) presented data from simultaneous pH monitoring by wireless Bravo and catheter mounted antimony electrode systems. Both studies demonstrated that the wireless system recorded significantly fewer reflux events; the effect on overall acid exposure was more limited. Further analysis revealed that events “missed” by the Bravo system were shorter and less acidic than those detected by both systems. The authors suggested that the different recording characteristics of the two systems explain the apparent “higher sensitivity” of the catheter pH system, including the lesser sampling rate of the Bravo system, and the systematic inaccuracy in catheter electrode calibration (not assessed by Bruley des Varannes et al).

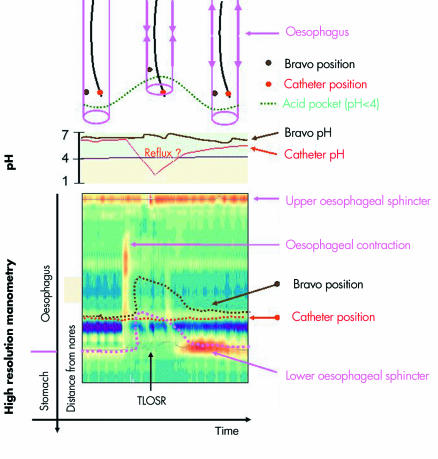

Beyond these technical concerns, the significance of short “reflux events” is questionable because short drops to pH <4 can be caused by factors unrelated to gastro‐oesophageal reflux: firstly, ingestion of mildly acidic fluids (despite instruction); secondly, as suggested by Pandolfino et al, movement of the catheter relative to the mucosa (that is, “drying” or “loss of contact” of the catheter electrode—the internal reference of the Bravo reduces this source of error); and thirdly, movement of the catheter relative to the gastro‐oesophageal junction (GOJ) during swallowing (fig 1). The last point requires explanation: on swallowing, the oesophagus shortens by several centimetres due to longitudinal muscle contraction,1,2 an event that stabilises the oesophageal wall and increases the effectiveness of peristaltic contraction and bolus transport.3 Even greater shortening can occur during oesophageal spasm4 and transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation (with or without acid reflux). As the oesophagus shortens, the catheter electrode moves distally towards the GOJ and may pass into the proximal stomach, a region in which highly acidic conditions may be present.5,6 Thus the catheter electrode may dip into the “acid pocket”6 at the GOJ before relaxation of the oesophagus returns the catheter into its original position. This cannot occur with the Bravo because it is fixed to the oesophageal wall. As a result, a short drop in pH is recorded by the catheter electrode but not the Bravo system.

Figure 1 Concurrent high resolution manometry (HRM) and pH recording during a transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation (TLOSR) in a normal volunteer. The positions of the Bravo capsule, catheter electrode, and LOS are indicated on the schematic diagram and the HRM plot. TLOSR was associated with brief oesophageal contraction with ∼5 cm shortening. The position of the Bravo capsule remained constant relative to the LOS and the Bravo pH recording remained at ∼pH 6; however the catheter electrode approached the LOS and recorded a short pH drop to <4 as it entered the “acid pocket”. Relaxation of the oesophagus restored the position of the LOS and the catheter pH recording normalised without swallowing activity. This “reflux event” was an artefact, related to oesophageal shortening rather than gastro‐oesophageal reflux. UOS, upper oesophageal sphincter.

As stated by the authors, pH studies alone cannot explain the discrepancies between the catheter and Bravo systems. Studies that combine pH monitoring (chemical reflux and clearance) and multichannel intraluminal impedance (volume reflux and clearance) with manometry are required to define the physiology of these events and help determine their relevance (if any) in eliciting symptoms. Studies using polymodal measurements have shown that oesophageal volume clearance is considerably faster than chemical clearance.7,8 Chemical clearance usually progresses by stepwise increases in pH as swallowing activity brings bicarbonate containing saliva into contact with acid reflux. However, short pH drops (often <20 seconds) can occur with peristaltic contractions and resolve without further swallowing activity. Short pH drops are also seen during transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation (fig 1), again resolving without swallowing activity. These observations strongly suggest that many short “reflux events” recorded by catheter systems may be artefacts, related to oesophageal shortening rather than gastro‐oesophageal reflux.

The Bravo system is a well tolerated alternative to catheter based pH measurement, experience with the technique is increasing, and normal values are being established. If the accuracy (specificity) of catheter based detection of reflux events is shown to be limited, the Bravo system may establish itself as the new standard for pH measurement in the investigation and diagnosis of gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease.

Acknowledgements

The HRM image of the TLOSR was obtained during research at the Department of Gastroenterology, University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland, under the guidance of Professor Michael Fried and Dr Werner Schwizer.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Pouderoux P, Lin S, Kahrilas P J. Timing, propagation, coordination, and effect of esophageal shortening during peristalsis. Gastroenterology 19971121147–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahrilas P J, Wu S, Lin S.et al Attenuation of esophageal shortening during peristalsis with hiatus hernia. Gastroenterology 19951091818–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pal A, Brasseur J G. The mechanical advantage of local longitudinal shortening on peristaltic transport. J Biomech Eng 200212494–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox M, Hebbard G, Janiak P.et al High‐resolution manometry predicts the success of oesophageal bolus transport and identifies clinically important abnormalities not detected by conventional manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil 200416533–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fletcher J, Wirz A, Henry E.et al Studies of acid exposure immediately above the gastro‐oesophageal squamocolumnar junction: evidence of short segment reflux. Gut 200453168–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher J, Wirz A, Young J.et al Unbuffered highly acidic gastric juice exists at the gastroesophageal junction after a meal. Gastroenterology 2001121775–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koek G H, Vos R, Flamen P.et al Oesophageal clearance of acid and bile: a combined radionuclide, pH, and Bilitec study. Gut 20045321–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sifrim D, Castell D, Dent J.et al Gastro‐oesophageal reflux monitoring: review and consensus report on detection and definitions of acid, non‐acid, and gas reflux. Gut 2004531024–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]