We describe the pattern of oesophageal pressure changes noted during high resolution manometry in a patient with achalasia. Our data indicate that longitudinal muscle contraction of the oesophagus is the major mechanism responsible for emptying the oesophageal contents against a poorly relaxing lower oesophageal sphincter. This phenomenon may enable patients with achalasia to empty the oesophagus and thus to relieve discomfort and maintain an adequate nutritional status.

Achalasia (Greek for “lack of relaxation”) is a primary oesophageal motility disorder characterised by the absence of oesophageal peristalsis due to damages of the myenteric plexus. Typically, patients with achalasia report difficulties in swallowing both liquids and solids (dysphagia) but young patients may initially complain of chest pain and regurgitation. These patients have mostly normal endoscopy (that is, no food retention) and initially do not loose weight, which leads to a delay in establishing this diagnosis.

Clearance of the aperistaltic oesophagus of patients with achalasia is thought to occur passively as the hydrostatic pressure of the column built in the oesophagus distends and opens the poorly relaxing lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS). However, patients with achalasia often have a high lower oesophageal sphincter pressure (that is, above 45 mm Hg). For a column of fluid to overcome hydrostatic pressures of this magnitude it would have to exceed 61 cm in height (that is, almost threefold the length of a normal human oesophagus). We hereby show a case which implies that another mechanism may be involved. Our observations are based on changes noted during high resolution manometry testing in a patient with achalasia.

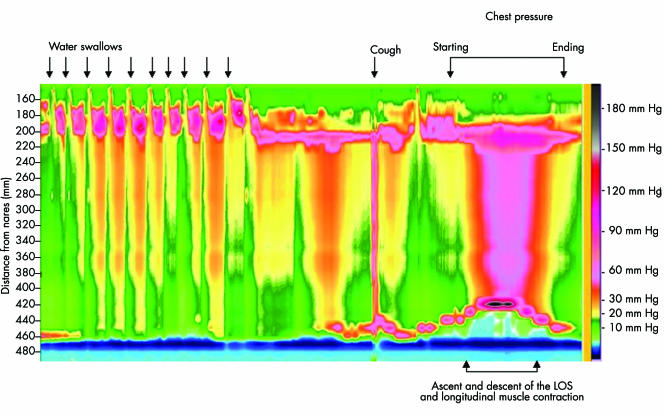

A manometric examination was performed in a 45 year old Caucasian male who had complained for the past three years of difficulty in swallowing both liquids and solids and retrosternal chest pressure after meal intake, to prove the suspected diagnosis of achalasia. Upper endoscopy was normal and a barium oesophagogram identified a normal sized oesophagus with the typical bird beak appearance at the gastro‐oesophageal junction. A 32 channel oesophageal manometry catheter was introduced transnasally and positioned in the oesophagus such that it spanned the entire oesophagus, including both upper and lower oesophageal sphincters. The diagnosis of achalasia was confirmed by the low amplitude mirror image intraoesophageal pressure changes during swallowing of 10 ml of water in the recumbent position, a high LOS resting pressure of 50 mm Hg, and an LOS residual pressures of 11 mm Hg during swallowing. The patient was then asked to sit up and to reproduce his symptoms of retrosternal pressure/pain by repeated swallowing liquid. After 10 water swallows he stopped and reported a sensation of chest fullness. Approximately 10 seconds later he reported increasing discomfort of retrosternal chest pressure immediately followed by the sensation of bolus passage and pressure relief. The pressure recordings during this period are shown in fig 1 and represent the aperistaltic pressure changes during swallowing followed by a brief period of inactivity. After a dry swallow the pressure in the oesophagus increases as the LOS is moving upwards and the fluid column is pressed against the closed upper oesophageal sphincter. Subsequently, the pressure is declining and the lower oesophageal sphincter returns to the initial position.

Figure 1 Topographic representation of a high resolution (32 channel) manometric recording of the events of oesophageal filling and emptying in a patient with achalasia. After 10 swallows the oesophagus is filled with water. Elevation of the pressure transition zone corresponding to the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) is assumed to be the result of the reflex contraction of the longitudinal musculature of the oesophagus. At the time of rise in intraoesophageal pressure, the patient reports an increase in chest pressure which improves once the oesophageal pressure returns to baseline. During this time the upper oesophageal sphincter (pressure band between 20 and 22 cm from nares) remains closed.

We interpret these changes as a reflex shortening of the longitudinal oesophageal musculature against the closed upper oesophageal sphincter, resulting in the generation of sufficient pressures to evacuate oesophageal contents into the stomach through the hypertensive and poorly relaxing lower oesophageal sphincter. The presence of this oesophageal propulsive force has been previously described by Winship and Zborlaske1 as the oesophageal response to acute obstruction. While shortening of the oesophagus during swallowing has previously been documented in normal subjects,2,3 this is the first report to describe it in a patient with achalasia. Our observation stimulates questions on the pathophysiology of achalasia and the role of oesophageal longitudinal musculature contraction. This, as we call it, “pump gun” (after the classic side action firearm first patented in Britain by Alexander Bain in 1854) oesophageal emptying, may enable patients with achalasia to clear the oesophagus, relieve pain, and maintain an adequate nutritional status.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Winship D H, Zboralske F F. The esophageal propulsive force: esophageal response to acute obstruction. J Clin Invest 1967461391–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pouderoux P, Lin S, Kahrilas P J. Timing, propagation, coordination, and effect of esophageal shortening during peristalsis. Gastroenterology 19971121147–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edmundowicz S A, Clouse R E. Shortening of the esophagus in response to swallowing. Am J Physiol 1991260G512–G516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]