Abstract

Introduction

Therapeutic strategies to treat chronic pancreatitis (CP) are very limited. Other chronic inflammatory diseases can be successfully suppressed by selective cyclooxygenase 2 (COX‐2) inhibitors. As COX‐2 is elevated in CP, we attempted to inhibit COX‐2 activity in an animal model of CP (WBN/Kob rat). We then analysed the effect of COX‐2 inhibition on macrophages, important mediators of chronic inflammation.

Methods

Male WBN/Kob rats were continuously fed the COX‐2 inhibitor rofecoxib, starting at the age of seven weeks. Animals were sacrificed 2, 5, 9, 17, 29, 41, and 47 weeks later. In some animals, treatment was discontinued after 17 weeks, and animals were observed for another 24 weeks.

Results

Compared with the spontaneous development of inflammatory injury and fibrosis in WBN/Kob control rats, animals treated with rofecoxib exhibited a significant reduction and delay (p<0.0001) in inflammation. Collagen and transforming growth factor β synthesis were significantly reduced. Similarly, prostaglandin E2 levels were markedly lower, indicating strong inhibition of COX‐2 activity (p<0.003). If treatment was discontinued at 24 weeks of age, all parameters of inflammation strongly increased comparable with that in untreated rats. The correlation of initial infiltration with subsequent fibrosis led us to determine the effect of rofecoxib on macrophage migration. In chemotaxis experiments, macrophages became insensitive to the chemoattractant fMLP in the presence of rofecoxib.

Conclusion

In the WBN/Kob rat, chronic inflammatory changes and subsequent fibrosis can be inhibited by rofecoxib. Initial events include infiltration of macrophages. Cell culture experiments indicate that migration of macrophages is COX‐2 dependent.

Keywords: chronic pancreatitis, macrophages, cyclooxygenases, infiltration, fibrosis

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a disease with a succession of pathophysiological events: inflammatory infiltration and necrosis are followed by fibrosis, sometimes pancreatic stone formation and diabetes mellitus, and an increased long term risk of pancreatic cancer. Therapeutic strategies to treat CP are mostly symptomatic and very limited. Other chronic inflammatory diseases have been successfully treated by specifically targeting COX‐2.

Elevated COX‐2 levels have been identified in pancreatic tissue from patients with CP.1,2 The secretory products of the COX system are prostaglandins (PG), primarily PGE2, acting in an autocrine or paracrine fashion. It is unclear whether PGE2 produced by pancreatic cells promotes inflammation. Furthermore, it is unclear whether the infiltrating inflammatory cell population of the pancreas (for example, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages) expresses COX‐2. These inflammatory cells are attracted to the pancreas and promote the destruction of the parenchyma, and by their phagocytic activity remove dying cells and cell debris.

The infiltrating population of leucocytes in CP consists of a high number of mononuclear cells, suggesting that macrophages make an important contribution to the inflammatory process.3 Macrophages are recruited from circulating monocytes and are activated by a number of cytokines, as well as by bacterial substances such as endotoxin. Activation induces phagocytic activity4,5 as well as upregulation of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX‐2). COX‐2 inhibitors have been used in a number of chronic inflammatory diseases.6,7

In animal models of acute pancreatitis, COX‐2 activity increased after induction of pancreatitis by cerulein.8 Mice without a functional COX‐2 gene on the other hand exhibited an attenuated severity of the disease,9,10 supporting the concept that the pancreas might be a target for COX‐2 specific therapy.

To study CP, the WBN/Kob rat is a widely used model.11 It mimics pathophysiological processes of chronic inflammation and fibrosis, although initiation differs from human CP. This model has been used to test potential therapeutic agents (for example, prednisolone12 and troglitazone13) which had a limited anti‐inflammatory effect. So far, the most successful drugs suppressing fibrosis are lisinopril, an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, and candesartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist.14,15

In this report, we address the question of whether the COX‐2 inhibitor rofecoxib suppresses inflammation and subsequent fibrosis in the WBN/Kob rat model of CP. We show that due to rofecoxib, progression of the disease is significantly suppressed and delayed and suggest a direct effect of the inhibitor on macrophage migration.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male rats were purchased from BRL Füllinsdorf, Switzerland (Wistar) and WBN/Kob rats from Japan LSC Inc., Shizuoka and TGC INC, Tokyo, Japan.16 Rats were housed as reported previously.16

Prior to sacrifice, rats were deprived of food overnight (16–18 hours) with free access to water. All manipulations conformed to Swiss federal guidelines on animal experiments and were approved by the local ethics committee.

Treatment with rofecoxib or lisinopril

After an adaptation period of three weeks, animals were fed the pure COX‐2 inhibitor rofecoxib, a gift from Merck, USA, mixed with powdered rat chow. According to the manufacturer's recommendations, 10 mg/kg body weight per day were administered. A defined amount of food (50 g/rat per day) was given with a rofecoxib content of 50 mg/kg. Control rats received the same amount of food without rofecoxib. Food consumption was monitored every two days. The assigned amount was completely consumed by animals in both the control and treatment groups. There were no significant differences in body weight development between the two groups.

The treatment regimen was as follows: starting at age seven weeks, animals were given the inhibitor continuously until they were sacrificed after 9, 12, 16, 24, 36, 48, and 54 weeks of age. In treatment regimen II, the same dose was given up to week 24 and then control food was given for an additional 12 (age 36) or 24 weeks (age 48) when the rats were sacrificed.

Lisinopril, a generous gift from AstraZeneca (Switzerland), was supplied continuously (10 mg/rat/day),14 starting at age seven weeks, until 16 weeks, when the animals were sacrificed.

Specimen

Organs were harvested as reported previously.16

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

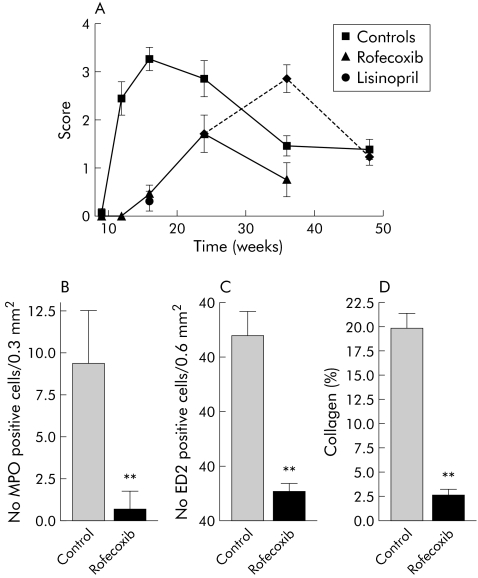

A score describing early and late inflammatory changes of exocrine pancreatic tissue was established based on the criteria shown in fig 3. Tissue damage was scored by assessing various parameters: infiltration by inflammatory cells (macrophages, neutrophilic granulocytes, and lymphocytes), acinar cell apoptosis, oedema, haemorrhage, formation of granulation tissue, proliferation of myofibroblastic cells, fibrosis, and scarring. Changes were graded according to their extent: score 1, changes affecting a single lobule; score 2, changes affecting two or more distinct lobules; score 3, confluent changes leading to effacement of the lobular structure; and score 4, changes affecting the majority of the section, defined by at least three areas of confluent change. Scoring of the different parameters was summarised to form a histology score. Histology scoring was performed in a blinded fashion by a pathologist (AP) experienced in pancreatic pathology.

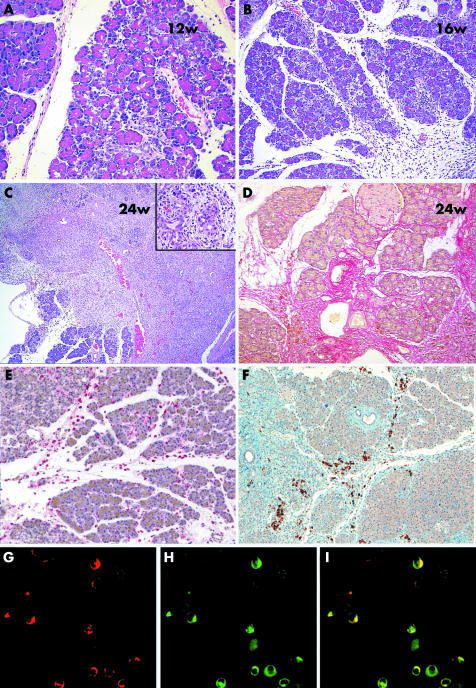

Figure 3 Analysis of histological changes in the pancreas of WBN/Kob rat. (A) Early changes with oedema, apoptosis of acinar cells, as well as interacinar inflammatory infiltrates consisting of histiocytes, lymphocytes, and neutrophilic granulocytes (week 12). (B) Confluent early changes affecting a group of adjacent lobules (week 16). (C) Confluent late changes with destruction of the lobular architecture; inset demonstrates formation of tubular complexes (week 24). (D) Sirius red staining of collagen fibrils. (E) Immunohistochemistry for ED2 (CD163), staining macrophages (red stain). (F) Immunohistochemsitry for cyclooxygenase 2 (COX‐2) (brown stain). (G–I) Colocalisation of ED1 (CD68) (G) and COX‐2 (H), and superimposition of the two pictures (I) on frozen sections.

To determine the extent of fibrosis, sections were stained by Sirius red, which preferentially labels collagen fibrils with red colour. Non‐fibrotic areas retain a blue colour. The morphometry software “Analysis” was used to analyse 10 low power fields per section. The percentage collagen positive area is given.

For detection of macrophages, antibodies against CD68 (ED1) and CD163 (ED2) were used. Positive cells were counted in 10 independent fields of vision per section and expressed as cells per 0.6 mm2.

For COX‐2 immunohistochemistry, an antibody against rat COX‐2 (Cayman) was used at a dilution of 1:200. Slides were pretreated by boiling in Tris buffer, pH 8.5, for 30 minutes on an automated slide processing system (Ventana Benchmark, Tucson, Arizona, USA).

RNA extraction and real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

RNA was extracted and used for real time PCR, as described previously.16 The primers were from Applied Biosystems based on the rat genes coding for COX‐1, COX‐2, tumour necrosis factor α (TNF‐α), and interleukin (IL)‐6.

COX‐1_forward CCA GCC CAA CTC CCT C

COX‐1_FAM CAT CTC TAT CAT GCT CTC CCC AAA

COX‐1_reverse GGG CTG ATG CTG GAG AAG TG

COX‐2_forward CCA TGT CAG GGA TCT TTC TTT TCT CA

COX‐2_FAM CTT CCT ACG CCA GCA ATC TGA

COX‐2_reverse CAA GGA AGG TCT GAT TGT C

IL‐6_forward GCC CTT CAG GAA CAG CTA TGA

IL‐6_FAM CAT CAG TCC CAA GAA GGC AAC T

IL‐6_reverse TCC GCA AGA GAC TTC

TNF‐α_forward GCT CCC TCT CAT CAG TTC CAT

TNF‐α _FAM GGC TTG TCA CTC GAG TTT TGA GAA

TNF‐α _reverse CCT CAC ACT CAG ATC AT

Primers coding for collagen α1(III), transforming growth factor β (TGF‐β), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP‐1), and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP‐1α) were designed as published previously.17,18

Real time PCR was run on a Taqman 7000 (Applied Biosystems, Switzerland) under standard conditions.

Transcript levels were quantified using 18S RNA (Applied Biosystems) as a reference and normalised to six week old Wistar rats16 or nine week old WBN/Kob control rats, respectively.

PGE2 ELISA

PGE2 was purified from pancreatic tissue using Amprep Octadecyl C18 Minicolumns (Amersham, Otelfingen, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The collected ethyl acetate fractions were evaporated to dryness under nitrogen. Purified PGE2 was quantified with an EIA PGE2 kit (Amersham).

Cell culture experiments

The cell line RAW264.7 was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, Virginia, USA). Cell culture medium and supplements were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carsbad, California, USA). TPP plastic wares and cell culture inserts for chemotaxis assays (8 μM pore size) were obtained from Milian (Geneva, Switzerland). For chemotaxis assays, 0.5×106 viable cells (above 95%) were seeded on top of 24 well filter inserts. Medium containing various amounts of N‐formyl‐L‐methionyl‐L‐leucyl‐L‐phenylalanine (fMLP) (Sigma Buchs, Switzerland) was placed at the bottom for one hour before harvesting the cells and quantitative analysis by a cell counter (FACSCalibur; Becton‐Dickinson, Basel, Switzerland).

Protein quantification

Protein contents in tissue homogenates were determined by a commercially available reagent (Pierce, Socochim, Lausanne, Switzerland) and quantified against bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Statistics

The effect of treatment was statistically analysed by two way ANOVA. When single time points were analysed, a one way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison post test was used.

Results

COX‐1 and ‐2 mRNA increase in WBN/Kob rats during inflammation

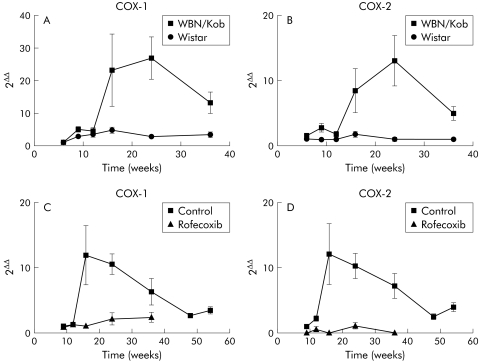

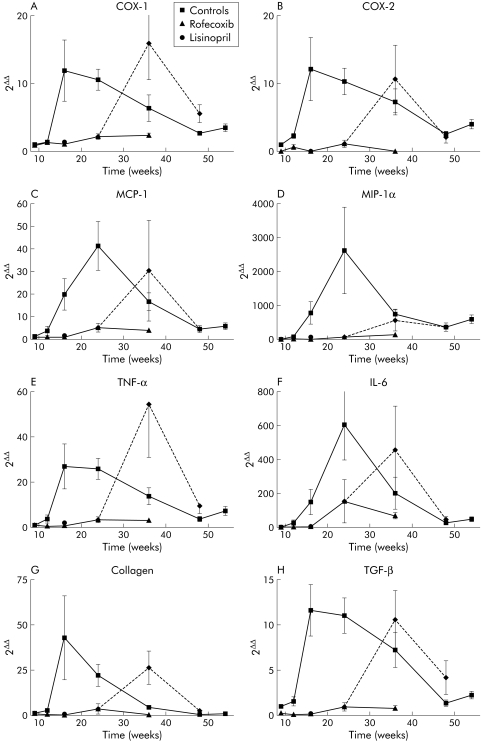

To test whether COX levels are increased during the inflammatory process in the WBN/Kob rat, we determined transcript levels of COX‐1 and COX‐2 in both WBN/Kob and Wistar rats, from an experiment previously described.16 At weeks 16 and 24, COX‐1 levels increased more than 25‐fold in WBN/Kob rats compared with control Wistar rats (fig 1A). COX‐2 levels increased approximately 15‐fold at the same time (fig 1B).

Figure 1 (A, B) Presence of cyclooxygenase (COX)‐1 and COX‐2 transcripts in the pancreas of WBN/Kob and Wistar rats. RNA was extracted from pancreata of both strains. After reverse transcription, cDNA was amplified using specific primers for COX‐1 and COX‐2 DNA. On real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the number of cycles were corrected by an internal standard (18S). Finally, the number of cycles of the experimental animals was calculated using Wistar rats at six weeks as a reference point (2ΔΔ). (A) COX‐1 levels of Wistar and WBN/Kob. (B) COX‐2 levels. Values are mean (SEM). Both genes were significantly different between strains (ANOVA, p<0.01). (C, D) Presence of COX‐1 and COX‐2 transcripts in the pancreas of control and rofecoxib treated WBN/Kob rats, as determined by real time PCR. (C) COX‐1, (D) COX‐2. Values are mean (SEM) for WBN/Kob controls and rofecoxib treated WBN/Kob rats. Curves were significantly different (p<0.001, two way ANOVA). Note, experiments presented in (A, B) were performed with WBN/Kob rats bred several years ago when the strain demonstrated peak inflammatory changes at approximately week 24. Over the years, disease development in this strain seems to have accelerated, and in more recent times peak changes are observed at approximately week 16 (C, D).

Chronic application of a COX‐2 inhibitor reduces COX transcript levels

Based on increased COX transcript levels, we administered a COX‐2 inhibitor (rofecoxib) continuously to WBN/Kob rats, starting at seven weeks of age, to test whether selective inhibition of COX‐2 would have a beneficial effect on pancreatic inflammation and fibrosis. Control WBN/Kob rats received the same amount of chow without rofecoxib. Rats were treated up to week 36 to test the long term effects of the drug. COX transcript levels of treated rats were clearly reduced compared with untreated controls. There was no selective regulation of one of the genes coding for COX‐1 (fig 1C) or COX‐2 (fig 1D). We conclude that chronic application of COX‐2 inhibitor targets inflammatory cells that migrate into the pancreas, and that due to the relative paucity of inflammatory cells in treated rats, both COX‐1 and COX‐2 are present in lower amounts.

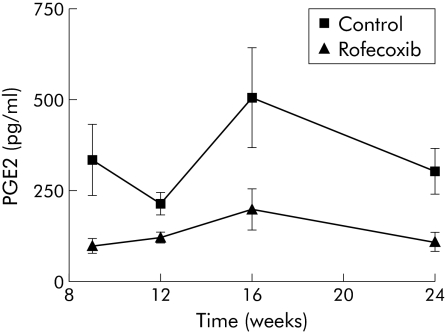

Inhibition of COX‐2 affects prostaglandin E2 levels in the pancreas

The presence of COXs is demonstrated indirectly by assessing PGE2, the active secretory product of the enzymatic cascade initiated by COXs. Figure 2 demonstrates a significant reduction in PGE2 levels up to week 24 in animals treated with rofecoxib. We conclude that systemic inhibition of COX‐2 lowers PGE2 secretion in the pancreas. In comparison, animals treated with lisinopril for nine weeks (an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor), exhibited a similar reduction in PGE2 levels (data not shown).

Figure 2 Demonstration of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production in WBN/Kob rats with and without rofecoxib treatment. Prostaglandins were extracted from pancreatic tissue, purified, and quantified by an ELISA. The amount of PGE2 was normalised to the protein in the extract. Values are mean (SEM) for controls and rofecoxib treated rats. The difference between controls and rofecoxib treatment was significant (p<0.0003, two way ANOVA).

Continuous application of a COX‐2 inhibitor improves histopathological parameters

Application of the COX‐2 inhibitor rofecoxib reduced the presence of COX‐1 and COX‐2 mRNA significantly and caused a reduction in PGE2 levels in pancreatic tissue. Therefore, we investigated whether tissue injury and subsequent fibrosis were also alleviated. This was carried out by analysis of haematoxylin‐eosin stained sections. CP in the WBN/Kob rat is characterised by focal infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils, together with oedema, the early phase of the disease (fig 3A, B). Late changes include the appearance of fibrosis, collagen deposition, granulation tissue, and the formation of tubular complexes (fig 3C, and inset in 3C). Histopathological assessment demonstrated significant deposition of collagen fibrils, as shown by Sirius red staining (fig 3D). An experienced pathologist evaluated the sections in a blinded manner. There was an obvious reduction in macrophages. To quantitate these cells, we performed immunohistochemistry of ED2 (CD163), an indicator of macrophages (fig 3E). Foam‐like cells were found predominantly in the vicinity of parenchymal destruction. Furthermore, we stained similar sections with an antibody against COX‐2. Figure 3F clearly demonstrates that COX‐2 is localised to infiltrating cells, again with a foam cell‐like appearance, suggesting that these cells are macrophages containing COX‐2. To further elucidate whether COX‐2 is expressed in macrophages, double staining of ED2/COX‐2 was performed on frozen sections. Figure 3G–I demonstrates that a significant population of macrophages are COX‐2 positive.

Histological assessment in fig 4A clearly demonstrates significant inhibition of inflammatory infiltration. As a next step, we investigated the effect of treatment on markers of acute and chronic infiltration. Neutrophilic granulocytes, markers of acute inflammation stained by myeloperoxidase, were significantly reduced (fig 4B). Macrophages are promoters of chronic inflammation; we counted them by immunohistochemistry using ED2 (CD163). While they were present in rather high numbers in untreated WBN/Kob rats, these numbers decreased in COX‐2 inhibitor treated animals (fig 4C).

Figure 4 Histopathology of the pancreas with and without treatment with a specific cyclooxygenase 2 (COX‐2) inhibitor (rofecoxib). Animals were sacrificed at the indicated time points and processed for sectioning and haematoxylin‐eosin staining, immunohistochemistry, or Sirius red staining. The score included early and late inflammatory changes and fibrosis, as described in fig 3 and in materials methods: a score of 1 was given when one lobule was affected, 2 when two or more were affected, 3 when inflammation or fibrosis was confluent over several lobules, and 4 for extended changes. Tissue specimens were scored in a blinded fashion and are shown as means (SEM). (A) Histopathology scores in controls and rofecoxib treated rats were significantly different (ANOVA, p<0.001). Broken line indicates rats treated until week 24. (B) Number of myeloperoxidase (MPO) positive cells (neutrophilic granulocytes) per 0.3 mm2. Sections from animals aged 16 weeks were analysed (that is, non‐treated controls and rofecoxib treated rats). Values are means (SEM). (C) Number of ED2 positive cells (macrophages) per 0.6 mm2 in sections from animals 16 weeks of age. (D) Morphometric quantification of collagen fibrils by Sirius red staining in 24 week old animals. Treatment groups in B–D were significantly different from untreated groups (ANOVA, **p<0.01).

Inhibition of COX‐2 affects fibrosis

In support of the observation that the initial inflammation determines chronic changes, we quantified the extent of collagen fibril deposition in 24 week old rats. Sections were stained with Sirius red, differentially highlighting collagen fibrils (fig 3D). Sections were then analysed morphometrically. In untreated rats, collagen deposition was found in the parenchyma covering 20% of the tissue area. Rofecoxib treated rats exhibited low collagen deposition, indicating that suppression of inflammatory infiltration had a decisive effect on fibrosis (fig 4C).

Termination of treatment is followed by an increase in inflammation and fibrosis

The data presented in fig 4 strongly suggest that pancreatic inflammation is associated with fibrosis. To further test whether in the WBN/Kob rat fibrosis is inflammation dependent, some rats received rofecoxib treatment until week 24 and were kept for another 12 or 24 weeks (ages 36 and 48 weeks) without rofecoxib. Animals treated continuously until week 36 demonstrated (fig 4A) a reduction in the histopathological score after a peak at week 24. When treatment was discontinued (broken line, fig 4A), histopathological scores increased to values seen in untreated rats. We conclude that acute inflammation is a prerequisite for extensive fibrosis and that COX‐2 inhibitors can significantly reduce both.

The observation that inflammation increased again after discontinuation of rofecoxib treatment was also supported by detection of mRNAs coding for COX‐1 and COX‐2, which significantly increased after treatment with rofecoxib was discontinued (fig 5A, B).

Figure 5 Presence of mRNA coding for cyclooxygenase (COX)‐1, COX‐2, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP‐1), macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP1‐α), tumour necrosis factor α (TNF‐α), interleukin 6 (IL‐6), transforming growth factor β (TGF‐β), and collagen α1(III) in pancreata of non‐treated control WBN/Kob rats, in rofecoxib treated rats, and in those with treatment discontinued at week 24. mRNAs were determined by reverse transcription and real time polymerase chain reaction. Values are mean (SEM) for control and rofecoxib treated rats, rats treated until week 24 (broken line), and rats at week 16 that were given lisinopril. (A) COX‐1, (B) COX‐2, (C) MCP‐1, (D) MIP1‐α, (E) TNF‐α, (F) IL‐6, (G) collagen α1(III), (H) TGF‐β.

mRNA levels of chemoattractants and cytokines correlate with infiltration and tissue injury

To determine whether chemoattractant proteins are generated in the pancreas of untreated WBN/Kob rats, mRNA levels of MCP‐1 (fig 5C) and MIP‐1α (fig 5D) were determined. MCP‐1 increased in parallel with the initial inflammation. In treated animals, there was a significant reduction indicating that the inhibitor reduced expression levels of this chemoattractant. Similarly, MIP‐1α levels were affected, although absolute expression levels appeared much lower (data not shown).

TNF‐α and IL‐6 have been detected in WBN/Kob rats in the early phase of inflammation.19 Figure 5E clearly demonstrates increasing TNF‐α mRNA (almost 50‐fold) in rats aged 16 weeks compared with nine week old WBN/Kob control rats. Thereafter, there was a slow decline in TNF‐α transcripts over the remaining period of inflammation and fibrosis. In animals which received rofecoxib, TNF‐α mRNA levels were significantly lower while levels increased as soon as treatment was stopped, reaching levels similar to those in untreated controls at 16 weeks.

Levels of IL‐6 mRNA also increased significantly and reached levels approximately 600‐fold higher than in nine week old rats (fig 5F). Again, treatment with rofecoxib caused a significant reduction in IL‐6 mRNA levels in the pancreas. However, these levels were still 150‐fold higher than in nine week old rats and in contrast with COX‐1, COX‐2, and TNF‐α, the IL‐6 peak was reached only at 24 weeks. After discontinuation of rofecoxib feeding, levels strongly increased (450‐fold higher than in nine week old rats). We conclude that both cytokines are present over the whole period of inflammation, with a correlation with disease activity.

Molecular markers of fibrosis are dependent on inflammation

Finally, we asked whether molecular markers of fibrosis (that is, TGF‐β and collagen) were affected by treatment. Collagen α1(III) mRNA levels strongly increased in untreated rats reflecting activation of collagen synthesis, presumably by myofibroblasts (fig 5G). In rofecoxib treated rats, mRNA levels were drastically reduced. In those animals in which treatment was discontinued, mRNA levels increased to those found in untreated rats. Similar to collagen mRNA, TGF‐β mRNAs were significantly increased in untreated controls while rofecoxib treatment reduced levels considerably (fig 5H). Parallel to the other parameters of fibrosis, TGF‐β levels strongly increased in animals where treatment was discontinued.

COX‐2 dependent macrophage migration

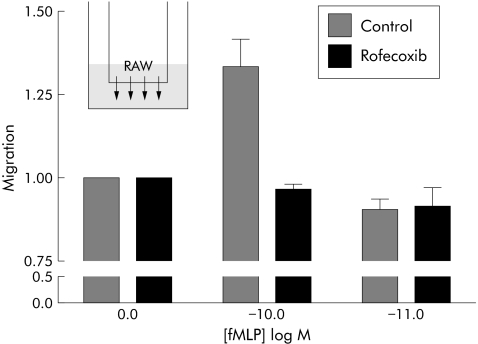

Based on the observation that macrophage infiltration was retarded in COX‐2 inhibitor treated rats, we asked whether COX‐2 activity might be involved in the regulation of macrophage migration. We performed cell culture assays in which a mouse macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7) was exposed to a known chemoattractant, fMLP, in a migration chamber. Various concentrations of fMLP were tested to demonstrate that the typical bell shaped dose‐response curve was achieved. Migration was accelerated at 10−10 M fMLP and reduced to control levels at 10−11 M. After addition of a COX‐2 inhibitor, fMLP mediated migration was abolished, suggesting that COX‐2 activity was required for the directional response (fig 6).

Figure 6 Migration of mouse macrophages towards a chemoattractant gradient. RAW264.7 cells were seeded in a chemotaxis chamber and exposed to 0, 10−10, and 10−11 M N‐formyl‐L‐methionyl‐L‐leucyl‐L‐phenylalanine (fMLP). After one hour, migrated cells were collected and counted. This experiment was repeated four times; unstimulated number of migrating cells was normalised to 1. Rofecoxib was given at a dose of 10 μM. Treatment groups were significantly different (ANOVA, p<0.03).

Discussion

Recent therapeutic advances in chronic inflammatory diseases using COX‐2 specific inhibitors led us to explore whether such an inhibitor was effective in an animal model of CP. We found a significant reduction in the severity of inflammation and in fibrotic changes in male WBN/Kob rats.

Although rofecoxib has recently been withdrawn from the market due to previously unknown cardiovascular side effects, COX‐2 inhibitors nevertheless seem excellent tools to understand the mechanism of inflammation in CP.

The WBN/Kob model spontaneously develops chronic inflammatory changes of the pancreas (for an overview, see Bimmler and colleagues16). The main characteristics of human CP, infiltration of inflammatory cells and fibrosis replacing the progressively destroyed exocrine parenchyma, are present in the WBN/Kob model. Furthermore, the spontaneous course of the disease can be observed in its early phases without experimental interference. Initiation of inflammation may however differ from human CP.

Changes in prostaglandin synthesis are an early key event in inflammatory processes. Cyclooxygenases play an important role in prostaglandin synthesis. While COX‐1 is constitutively expressed in many tissues and involved in modulation of normal physiological processes (see Smith and colleagues20), COX‐2 is regulated and inducible by injury through mediators of inflammation.20,21 Both COX isoforms are integrated in the enzymatic cascade, resulting in generation of PGG2, PGH2, and finally PGE2.

During inflammation in the WBN/Kob rat, COX‐1 and COX‐2 transcript levels increased up to 20‐fold (fig 1). Treatment with rofecoxib completely suppressed this increase. In (untreated) WBN/Kob rats with pancreatitis, PGE2 levels were 2.5‐fold. This increase in PGE2 levels demonstrates the relevance of elevated COX‐2 expression. Furthermore, in support of the COX‐2 transcript levels, we were able to demonstrate a significant reduction in PGE2 levels in rofecoxib treated rats.

In pancreatic tissue homogenates, the inducible COX‐2 transcripts are expected to be produced by inflammatory cells, particularly by macrophages. The reason for the concurrently increased COX‐1 levels seems unclear but it is probable that they represent constitutive expression in infiltrating cells.

In an acute model of pancreatitis, it was shown that a selective COX‐2 inhibitor (NS‐398) reduced prostaglandin E2 serum levels by a factor of two and improved the systemic effects of pancreatitis.22 In other acute pancreatitis models, celecoxib23 and parecoxib24 partially ameliorated pancreatic and systemic injury.

In our hands, COX‐2 immunoreactivity localised to macrophages, some other types of immune cells, and possibly stellate cells. The latter play an important role with regard to the development of fibrosis in CP.25,26,27,28 In our experimental work presented here, we concentrated on inflammatory cell infiltration, especially that of macrophages. In human pancreas from patients with CP, COX‐2 immunoreactivity has been detected in ductal cells and to some degree in degenerating acinar cells1,2; conflicting results have been published regarding the question of whether or not1 COX‐2 is upregulated in mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrates.12

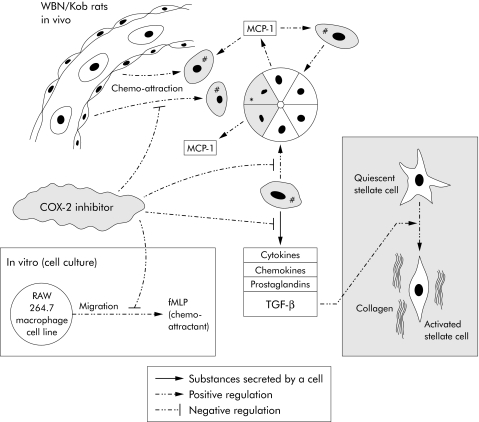

Figure 7 Acinar cell damage (*) leads to nearby accumulation of activated macrophages (#) due to chemoattraction (for example, exerted by monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP‐1) which is secreted in the vicinity of injured acinar cells). Activated macrophages produce and shed various cytokines, chemokines, prostaglandins, and transforming growth factor β (TGF‐β). The latter stimulates activation of stellate cells which consequently synthesise and deposit collagen fibres, eventually leading to fibrosis. Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX‐2) inhibitors interfere with different processes: they inhibit chemoattraction and the secretory activity of macrophages, especially secretion of TGF‐β. In our WBN/Kob rats we have shown that infiltration of macrophages and subsequent fibrosis are significantly reduced and delayed if rofecoxib, a COX‐2 inhibitor, is administered. Inset: In vitro experiments using a macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7) demonstrated a similar effect of rofecoxib. Directed migration of macrophages caused by the chemoattractant N‐formyl‐L‐methionyl‐L‐leucyl‐L‐phenylalanine (fMLP) was significantly reduced with rofecoxib. We therefore hypothesise that infiltration of activated macrophages represents an essential step in the pathogenesis of CP.

In addition to pancreatic mRNA‐levels of COX‐1 and COX‐2, those of the chemoattractants MCP‐1, MIP‐1α, and the cytokines TNF‐α, IL‐6, and TGF‐β were significantly diminished in rofecoxib treated rats compared with untreated WBN/Kob rats, reflecting diminished inflammation and fibrosis.

A blinded assessment of oedema, extent of infiltration of inflammatory cells, destruction of acinar tissue, and fibrosis demonstrated that treatment caused a significant reduction and delay in pancreatitis. Termination of treatment resulted in full re‐establishment of pancreatitis. This indicates that COX‐2 promotes inflammation during all phases of the disease, including fibrosis. To evaluate the extent of protection, we included a drug recently reported to suppress fibrosis in the WBN/Kob rat.14 For this purpose, animals received lisinopril for nine weeks prior to analysis at week 16. The histopathological score was similar to that of rofecoxib treated rats, indicating that the inflammatory cascade as well as fibrosis were significantly affected.

A similar effect was described after administration of an angiotensin II receptor antagonist.15 We do not know at present whether this is a mechanism independent of COX‐2 driven processes or whether there is an interaction between the two mechanisms. This needs to be investigated.

We used immunohistochemistry for MPO and ED2 (CD163) to dissect the composition of inflammatory cells. The number of neutrophilic granulocytes as well as macrophages was dramatically reduced by COX‐2 inhibition. In a model of acute pancreatitis, neutrophil infiltration was reduced to 40–50%9,10 in COX‐2−/− mice, a finding that is in agreement with our own data on neutrophils. In a further study of the role of macrophages, important mediators of chronic inflammation, we found a reduction after treatment and were able to localise COX‐2 protein to macrophages. To test the hypothesis that pancreatic infiltration by macrophages is COX‐2 dependent, we used in vitro migration assays.

fMLP, a known chemoattractant, induced migration of RAW264.7 cells. Rofecoxib reduced the response to the chemoattractant signal significantly (fig 6) without affecting the viability of the cells (data not shown). This suggests that systemically applied inhibitor may disrupt the signalling cascade for monocyte attraction and hence reduce the inflammatory response. Expression of COX‐2 in macrophages as well as reduced migration after COX‐2 inhibition argues in favour of a direct action of rofecoxib on macrophages.

We may not yet have reached the point where CP in humans can be influenced therapeutically. Recent detection of cardiovascular side effects of COX‐2 inhibitors restricts the use of these drugs.29 However, by studying and understanding the processes that seem to be controlled by COX‐2 or angiotensin II, new therapeutic approaches for a hitherto incurable disease might evolve with time.

In conclusion, we have shown in an animal model of CP that pancreatic inflammation, particularly macrophage invasion, is strongly reduced after administration of a COX‐2 inhibitor. Concurrently, histological and molecular markers of fibrosis indicated significant inhibition. We also demonstrated that COX‐2 inhibitors may directly affect the migratory behaviour of macrophages which contribute significantly to the acute and chronic phases of this disease. A possible pathophysiological mechanism is summarised in fig 7.

Acknowledgements

The study was generously supported by the “Amelie Waring Foundation”, Zürich, the “Jubiläumsspende für die Universität Zürich”, and by the bank UBS on behalf of an anonymous customer. We would like to thank M Bain, R Gassmann, and U Ungethüm for excellent technical assistance. Part of the project was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (to RG and DB).

Abbreviations

CP - chronic pancreatitis

COX - cyclooxygenase

TGF‐β - transforming growth factor β

PGE2 - prostaglandin E2

fMLP - N‐formyl‐L‐methionyl‐L‐leucyl‐L‐phenylalanine

MCP‐1 - monocyte chemoattractant protein 1

MIP‐1α - macrophage inflammatory protein 1α

MPO - myeloperoxidase

TNF‐α - tumour necrosis factor α

IL‐6 - interleukin 6

PCR - polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Schlosser W, Schlosser S, Ramadani M.et al Cyclooxygenase‐2 is overexpressed in chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 20022526–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koliopanos A, Friess H, Kleeff J.et al Cyclooxygenase 2 expression in chronic pancreatitis: correlation with stage of the disease and diabetes mellitus. Digestion 200164240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emmrich J, Weber I, Nausch M.et al Immunohistochemical characterization of the pancreatic cellular infiltrate in normal pancreas, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Digestion 199859192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper P H, Mayer P, Baggiolini M. Stimulation of phagocytosis in bone marrow‐derived mouse macrophages by bacterial lipopolysaccharide: correlation with biochemical and functional parameters. J Immunol 1984133913–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrios‐Rodiles M, Tiraloche G, Chadee K. Lipopolysaccharide modulates cyclooxygenase‐2 transcriptionally and posttranscriptionally in human macrophages independently from endogenous IL‐1 beta and TNF‐alpha. J Immunol 1999163963–969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matheson A J, Figgitt D P. Rofecoxib: a review of its use in the management of osteoarthritis, acute pain and rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs 200161833–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh G, Ramey D R, Morfeld D.et al Gastrointestinal tract complications of nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. A prospective observational cohort study. Arch Intern Med 19961561530–1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zabel Langhennig A, Holler B, Engeland K.et al Cyclooxygenase‐2 transcription is stimulated and amylase secretion is inhibited in pancreatic acinar cells after induction of acute pancreatitis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1999265545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song A M, Bhagat L, Singh V P.et al Inhibition of cyclooxygenase‐2 ameliorates the severity of pancreatitis and associated lung injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2002283G1166–G1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ethridge R T, Chung D H, Slogoff M.et al Cyclooxygenase‐2 gene disruption attenuates the severity of acute pancreatitis and pancreatitis‐associated lung injury. Gastroenterology 20021231311–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohashi K, Kim J H, Hara H.et al WBN/Kob rats. A new spontaneously occurring model of chronic pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol 19906231–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto T, Yamada T, Yokoi T.et al Apoptosis of acinar cells is involved in chronic pancreatitis in WBN/Kob rats: role of glucocorticoids. Pancreas 200021296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimizu K, Shiratori K, Hayashi N.et al Thiazolidinedione derivatives as novel therapeutic agents to prevent the development of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 200224184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuno A, Yamada T, Masuda K.et al Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor attenuates pancreatic inflammation and fibrosis in male Wistar Bonn/Kobori rats. Gastroenterology 20031241010–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamada T, Kuno A, Masuda K.et al Candesartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist, suppresses pancreatic inflammation and fibrosis in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 200330717–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bimmler D, Schiesser M, Perren A.et al Coordinate regulation of PSP/reg and PAP isoforms as a family of secretory stress proteins in an animal model of chronic pancreatitis. J Surg Res 2004118122–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakanishi K, Uenoyama M, Tomita N.et al Gene transfer of human hepatocyte growth factor into rat skin wounds mediated by liposomes coated with the sendai virus (hemagglutinating virus of Japan). Am J Pathol 20021611761–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe T, Higuchi K, Hamaguchi M.et al Monocyte chemotactic protein‐1 regulates leukocyte recruitment during gastric ulcer recurrence induced by tumor necrosis factor‐alpha. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2004287G919–G928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie M J, Motoo Y, Su S B.et al Expression of tumor necrosis factor‐alpha, interleukin‐6, and interferon‐gamma in spontaneous chronic pancreatitis in the WBN/Kob rat. Pancreas 200122400–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith W L, DeWitt D L, Garavito R M. Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu Rev Biochem 200069145–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith W L, Garavito R M, DeWitt D L. Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases (cyclooxygenases)‐1 and ‐2. J Biol Chem 199627133157–33160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foitzik T, Hotz H G, Hotz B.et al Selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) reduces prostaglandin E2 production and attenuates systemic disease sequelae in experimental pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology 2003501159–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alhan E, Kalyoncu N I, Ercin C.et al Effects of the celecoxib on the acute necrotizing pancreatitis in rats. Inflammation 200428303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Brien G, Shields C J, Winter D C.et al Cyclooxygenase‐2 plays a central role in the genesis of pancreatitis and associated lung injury. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 20054126–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luttenberger T, Schmid‐Kotsas A, Menke A.et al Platelet‐derived growth factors stimulate proliferation and extracellular matrix synthesis of pancreatic stellate cells: implications in pathogenesis of pancreas fibrosis. Lab Invest 20008047–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bachem M G, Schneider E, Gross H.et al Identification, culture, and characterization of pancreatic stellate cells in rats and humans. Gastroenterology 1998115421–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haber P S, Keogh G W, Apte M V.et al Activation of pancreatic stellate cells in human and experimental pancreatic fibrosis. Am J Pathol 19991551087–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Apte M V, Wilson J S. Mechanisms of pancreatic fibrosis. Dig Dis 200422273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bresalier R S, Sandler R S, Quan H.et al Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med 20053521092–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]