Original treatments, including corticosteroids, azathioprine, infliximab, ciclosporin, and interleukin 10 have been occasionally reported in refractory sprue patients with unsatisfactory results.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 We report on the clinical and histological efficacy of anti‐T chemotherapy (pentostatine) in a patient with a refractory sprue complicated by an ulcerative and stenotic jejunitis.

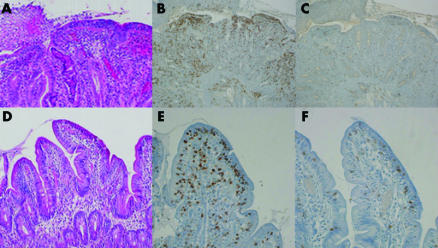

A 38 year old man diagnosed with refractory sprue in June 2002 developed ulcerative jejunitis in July 2003. Diagnosis led on the following: malabsorptive diarrhoea resistant to a gluten free diet (GFD); severe malnutrition (body mass index (BMI) 14.3 kg/m2); albuminaemia 11 g/l; diffuse total villous atrophy associated with jejunal ulcerations and a major intestinal intraepithelial CD3+ CD8− T lymphocyte population (IEL) (fig 1A–C); clonal T cell receptor γ rearrangement; negative circulating antigliadin and antitransglutaminase IgA and IgG antibodies (total IgA and IgG were normal); hyposplenism; no intestinal stenosis; and jejunal ulcerations but no evidence of an enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma (EATL) on endoscopic videocapsule, enteroscopy, or laparoscopy with small bowel, liver, and lymph node biopsies.

Figure 1 Jejunoileitis (A–C) on jejunal biopsy samples in July 2003, with total villous atrophy, ulceration, major intraepithelial lymphocyte infiltration (haemato‐eosine‐safran, A) widely expressing CD3 (immunoperoxidase, B) but rarely CD8 (immunoperoxidase, C). Villous regrowth (D–F) on jejunal biopsy samples in November 2004 after small bowel resection followed by combination treatment with pentostatine, budesonide, and a strict gluten free diet: no villous atrophy (hemato‐eosine‐safran, D), moderate CD3+ intraepithelial lymphocyte infiltrate (immunoperoxidase, E) with mixed CD8− and CD8+ populations (immunoperoxidase, F).

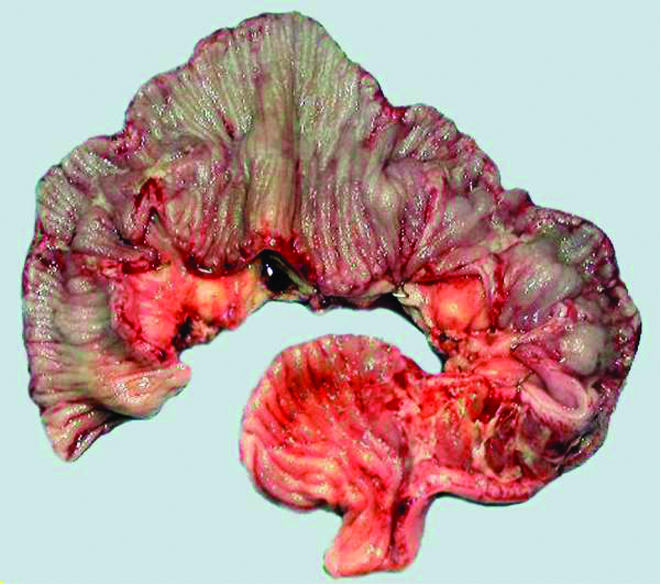

Total exclusive parenteral nutrition (PN), budesonide, and omeprazole (in an attempt to optimise jejunal release of enteric coated budesonide) led to a moderate improvement in September 2003 (BMI 15.4, albuminaemia 19 g/l, citrullinaemia 4 µmol/l (normal range 20–47))9. Strict GFD was reintroduced but intake remained low (800 kcal/day) because of nausea. Three jejunal stenosis were found and a 60 cm jejunal resection was performed in January 2004 (fig 2). Microscopic findings were similar to preoperative samples showing no sign of malignancy. Twelve infusions of pentostatine (Nipent 4 mg/m2—that is, 6 mg every two weeks) were administrated from March to September 2004 with no side effects, together with trimethoprime/cotrimoxazole, budesonide, omeprazole, and a strict GFD.

Figure 2 Stenosis and ulcerations (macroscopy, January 2004).

At the end of the chemotherapy period, improvement was noticeable: no diarrhoea, weaned off PN since April 2004, BMI 20.7, albuminaemia 44 g/l, and citrullinaemia 14 µmol/l. Two months later entero computed tomography, small intestine follow through radiography, and push and retrograde enteroscopy were considered normal. Duodenal biopsies showed partial villous atrophy whereas jejunal biopsies had no villous atrophy with a mixed IEL CD8+/CD8− up to 40 per 100 epithelial cells (fig 1D–F) with a persistent clonal T cell receptor γ rearrangement; GFD, budesonide, and omeprazole were continued. In November 2005 he remained symptom free, BMI 20.0, with stable biological parameters, including albuminaemia 36 g/l and citrullinaemia 11 µmol/l.

Pentostatine (a nucleoside analogue inducing T cell depletion) is commonly used in hairy cell leukaemia10 and chronic lymphoid leukaemia.11 It has been tested in hepatosplenic gamma/delta T cell lymphoma with promising efficacy.12 In eight patients with CD3+ CD8− refractory sprue treated with cladribine (another anti‐T nucleoside analogue),13 significant clinical improvement (weight gain, improvement in diarrhoea and hypoalbuminaemia) was noted in all but one case. Two patients showed histological improvement and a decrease in IEL. However, three patients died of EATL. In our patient treated with pentostatine and budesonide, tolerance was good and we observed a dramatic clinical and histological improvement, including not only villous regrowth but also reappearance of CD8+ T cell IEL. Because refractory sprue was fully reversible in this patient, as illustrated in fig 1, our original findings prompt us to propose this combination therapy for similar patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Professor Ming‐Qing Du (Pathology, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge), Professor Elisabeth MacIntyre (Pathology, Necker Enfants Malades Hospital, Paris), Professor Eric Oksenhendler (Haematology, Saint‐Louis Hospital, Paris), Dr Kouroche Vahedi, and Professor Patrice Valleur (Departement of Digestive Diseases, Lariboisière Hospital, Paris) for the care and/or investigations they provided for this patient.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Longstreth G F. Successful treatment of refractory sprue with cyclosporine. Ann Intern Med 19931191014–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaidya A, Bolanos J, Berkelhammer C. Azathioprine in refractory sprue. Am J Gastroenterol 1999941967–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rolny P, Sigurjonsdottir H A, Remotti H.et al Role of immunosuppressive therapy in refractory sprue‐like disease. Am J Gastroenterol 199994219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wahab P J, Crusius J B, Meijer J W.et al Cyclosporin in the treatment of adults with refractory coeliac disease—an open pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 200014767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulder C J, Wahab P J, Meijer J W.et al A pilot study of recombinant human interleukin‐10 in adults with refractory coeliac disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001131183–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maurino E, Niveloni S, Chernavsky A.et al Azathioprine in refractory sprue: results from a prospective, open‐label study. Am J Gastroenterol 2002972595–2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillett H R, Arnott I D, McIntyre M.et al Successful infliximab treatment for steroid‐refractory celiac disease: a case report. Gastroenterology 2002122800–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goerres M S, Meijer J W, Wahab P J.et al Azathioprine and prednisone combination therapy in refractory coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 200318487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crenn P, Vahedi K, Lavergne‐Slove A.et al Plasma citrulline: A marker of enterocyte mass in villous atrophy‐associated small bowel disease. Gastroenterology 20031241210–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jehn U, Bartl R, Dietzfelbinger H.et al An update: 12‐year follow‐up of patients with hairy cell leukemia following treatment with 2‐chlorodeoxyadenosine. Leukemia 2004181476–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dillman R O. Pentostatin (Nipent) in the treatment of chronic lymphocyte leukemia and hairy cell leukemia. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2004427–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corazzelli G, Capobianco G, Russo F.et al Pentostatin (2'‐deoxycoformycin) for the treatment of hepatosplenic gammadelta T‐cell lymphomas. Haematologica 200590ECR14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goerres M S, Wahab P J, Kerckhaert J O.et al Cladribine treatment in refractory coeliac disease type II. Digestive Diseases Week. Orlando, FL, USA 18–22 May 2003