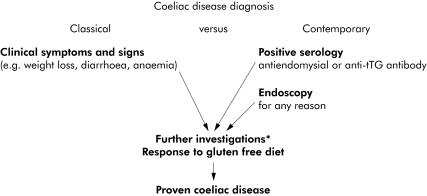

The management of coeliac disease is an increasing part of a gastroenterologist's workload. Recent prevalence studies suggest ∼1% of the general UK population have positive coeliac serology, which combined with increasing population and primary care awareness is leading to more and more referrals. The majority of contemporary referrals are now initially diagnosed by highly sensitive and specific serological tests followed by readily performed endoscopic biopsy (fig 1). Consequently, we now identify many more patients with no or only mild clinical symptoms, making the classical scenario of diarrhoea/steatorrhoea and weight loss a comparative rarity. Much of the early data on clinical aspects of classical coeliac disease (that is, published pre ∼1990) may not be applicable to contemporary coeliac disease. These changes in clinical practice have been paralleled by a dramatic increase in our knowledge of disease pathogenesis, making coeliac disease the best understood human “autoimmune” disorder. In this review article, we present selected major recent advances in both clinical and basic science aspects of coeliac disease, focusing on the many high quality studies published within the last five years.

Figure 1 Contemporary and classical diagnosis of coeliac disease. In the past, coeliac disease was mainly diagnosed after clinical presentation. This remains the description of disease in many textbooks. Nowadays, many more patients are referred on the basis of positive serological tests. Endoscopy and “routine” duodenal biopsy (without prior suspicion of coeliac disease) may also lead to diagnosis. *Serology, duodenal histology, HLA‐DQ genotyping. Adapted from Green et al 2005.106

Occurrence of coeliac disease

General population based prevalence studies of undetected coeliac disease

Several serological screening studies from Europe, South America, Australasia, and the USA have shown that approximately 0.5–1% of these populations may have undetected coeliac disease. The most consistent estimate reported from the largest population based studies is approximately 1%. The prevalence is even higher in first and second degree relatives of people with coeliac disease.1

In the five studies shown in table 1, general population based samples of children were recruited for coeliac disease screening. The two earlier Italian studies (using antigliadin antibody testing followed by antiendomysial antibody and small bowel biopsy) suggested a prevalence of 1 in 93 of undetected coeliac disease.2,3 These findings have been replicated in two further large studies, one from the UK and one from Finland. The recent Bristol study used blood stored anonymously for the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (a population based birth cohort study established in 1990).4 This study tested 5470 children for antitissue transglutaminase antibody and then those who were positive with a further antiendomysial antibody test. Maki et al tested 3654 Finnish students for both serological tests and offered small intestinal biopsy to those who were positive.5 Both of these studies found a prevalence of approximately 1 in 100.

Table 1 Coeliac disease prevalence in general population based studies: children.

| Area | Year, citation | Age (y)* | Proportion male (%) | Cases | No screened | Prevalence (95% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 19942 | 13 | 50 | 11 | 3351 | 0.33% (0.16–0.59) |

| Italy | 19993 | 6–14 | 53 | 17 | 1607 | 1.06% (0.62–1.69) |

| Sahara | 19996 | 7.4 | 53 | 56 | 989 | 5.66% (4.31–7.29) |

| Finland | 20035 | 7–16 | – | 37 | 3654 | 1.01% (0.71–1.39) |

| UK (Bristol) | 20044 | 7.5 | – | 54 | 5470 | 0.99% (0.74–1.29) |

*Mean (range).

†Prevalence (%) calculated from available data, with 95% confidence interval (CI) calculated using binomial distribution.

The study of Saharawi children by Catassi et al showed the highest coeliac disease prevalence (5%).6 This cohort, comprising refugees living in an Algerian province, was tested for antiendomysial antibody and a sample of positive individuals had small intestinal mucosa biopsy. Reasons for this high prevalence, which is markedly different to all the other general population estimates, are unclear. The authors speculated that coeliac disease might confer some “protection” against intestinal infections or parasites.

Selected adult general population based screening studies for coeliac disease are shown in table 2. Three of these studies used populations recruited for the World Health Organisation MONICA project (monitoring of trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease) and were similar in design, with samples randomly selected from population registers stratified by age and sex.7,8,9 All three of these studies (and the Argentinean study) used a combination of antigliadin antibody and antiendomysial antibody testing to identify people with previously undetected coeliac disease, but not all reported small intestinal biopsy. Other studies used antiendomysial antibody as the main test for identifying people with undetected coeliac disease.

Table 2 Coeliac disease prevalence in general population based studies: adults.

| Area | Year, citation | Age (y)* | Proportion male (%) | Cases | No screened | Prevalence (95% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ireland | 19977 | 15–65 | — | 15 | 1823 | 0.82 (0.46–1.35) |

| Italy | 1997125 | 44 (20–89) | 47 | 4 | 2237 | 0.18 (0.05–0.46) |

| Sweden | 19998 | 50 (25–74) | 50 | 10 | 1894 | 0.53 (0.25–0.97) |

| Spain | 2000126 | 45 (2–89) | 45 | 3 | 1170 | 0.26 (0.05–0.75) |

| France | 20009 | 35–64 | – | 3 | 1163 | 0.26 (0.05–0.75) |

| Italy | 2001127 | 12–65 | 48 | 17 | 3483 | 0.49 (0.28–0.78) |

| Argentina | 2001128 | 16–79 | 50 | 12 | 2000 | 0.60 (0.31–1.05) |

| Australia | 2001129 | 20–79 | 50 | 7 | 3011 | 0.23 (0.09–0.48) |

| England | 200310 | 59 (45–76) | 41 | 87 | 7527 | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) |

*Mean (range).

†Prevalence (%) calculated from available data, with 95% confidence interval (CI) calculated using the binomial distribution.

It is notable that the prevalence of undetected coeliac disease in both children and adults is very similar (approximately 1%) in the two recent large UK based studies.4,10 It therefore seems probable that the coeliac trait starts in early childhood in all cases, even in those who are subsequently diagnosed as adults. The search for the initial trigger resulting in the breakdown of oral tolerance to dietary wheat, rye, and barley therefore needs to focus on in utero events and early infancy. Why some adults suddenly develop symptoms in later life is unexplained and might reflect a later event in the control of immunological tolerance.

Prevalence studies of clinically diagnosed coeliac disease

Estimates of the prevalence of clinically diagnosed coeliac disease range from approximately 0.05% to 0.27%.11,12,13,14 From data in Derby, UK, the estimated prevalence of clinically diagnosed coeliac disease at the end of 1999 was 0.14%.15 These figures suggest that the current ratio (prevalence based) of clinically diagnosed to undetected cases—that is, “the size of the iceberg”—in the UK is approximately 1 in 8.

Incidence of coeliac disease in children and adults

Studies of childhood coeliac disease in the UK showed a general decline in incidence during the 1970s.16,17,18 Other countries, apart from Sweden, have also reported some evidence of a decline.19,20 More recently, some studies have suggested that the incidence of childhood coeliac disease may have been rising during the late 1980s and 1990s. There are differences across studies in case identification method: the use of hospital admission data, self‐ or parent reported diagnosis, and national coeliac society membership—all of which are liable to variation by ascertainment and therefore might explain some of the differences.

Data from Sweden reported by Ivarsson et al related the rise in childhood coeliac disease to infant feeding practices.21 The “Swedish epidemic” suggested that coeliac disease might be prevented in part by introduction of gluten while still breast feeding, and gluten introduction between 4 and 6 months of life, rather than before or after.22 It is plausible that these factors may help induce oral tolerance to dietary antigens in susceptible individuals. However, a recent population based study from the Netherlands reported no such change in infant feeding practices during the period studied, yet there was an increase in incidence.23

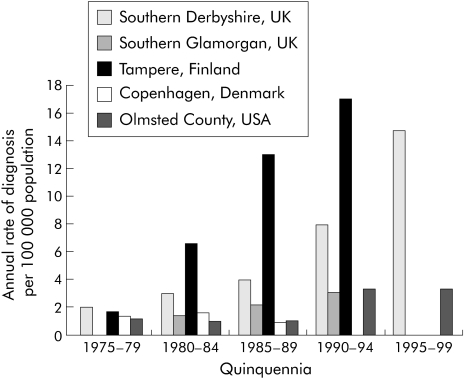

The rate of diagnosis of adult coeliac disease has risen dramatically in most areas of the world where there are data available to monitor such trends.11,12,13,24 The estimated annual rate of diagnoses from various areas is shown in fig 2. An interest in coeliac disease research in some centres probably combined with an active “case finding” strategy may explain the variation apparent in these figures. In combination with the diagnosed disease prevalence estimates they do indicate the substantial gap between the number of people with clinically diagnosed and undetected disease.

Figure 2 Estimated annual rate of diagnosis (by quinquennia) of coeliac disease from various geographical areas.

Clinical manifestations of coeliac disease

Although coeliac disease can be diagnosed at any age, it presents most commonly in either early childhood (between 9 and 24 months) or in the third or fourth decade of life.25,26,27,28,29 In contrast to the 1/1 sex ratio in children, twice as many females are diagnosed in adulthood. Although the “classical” gastrointestinal malabsorption syndrome characterised by diarrhoea, steatorrhoea, weight loss, fatigue, and anaemia may occur in severe cases, most patients have a milder constellation of symptoms such as abdominal discomfort, bloating, indigestion, or non‐gastrointestinal symptoms (or no symptoms at all).25,26,27,28,29 Since coeliac disease was first described, the clinical manifestation seen in the UK appears to be changing, with increasing numbers being diagnosed as a result of the investigation of anaemia and/or non “classical” symptoms.24,30,31,32,33

Hin et al recently carried out a case finding study in primary care in the UK.34 In this study, individuals with fatigue and/or with a past or present diagnosis of microcytic anaemia had the highest prevalence of previously undetected coeliac disease.

One explanation for any changes in presentation could be that the natural history of the disease is changing, perhaps in response to changing environmental stimuli such as infant feeding practices in children or cigarette smoking in adults. A more likely explanation is that the ability to make the diagnosis has improved (both better tests and greater test accessibility) throughout the last 20 years with the development of accurate serological markers of the disease and increasing use of endoscopic biopsy techniques. Therefore, a much broader spectrum of individuals are being investigated for coeliac disease and consequently being diagnosed (fig 1).

Impact of undetected coeliac disease

The implications of recognising undetected coeliac disease at a general population level are unclear because the few reported data on the morbidity and physiological characteristics associated with previously undetected disease are from small selected case series. Few studies so far have been able to analyse a wide variety of sociodemographic and physiological factors with respect to undiagnosed coeliac disease due to low sample size. Most adult screening studies in the general population have identified only small numbers of previously undiagnosed cases and have therefore been unable to examine any associations in comparison with the general population.35,36,37 Of the studies that have looked at the differences between clinically diagnosed disease and “screening” or previously undetected disease, most have focused on bone mineral density and anthropometric measurements. The findings suggest that people with undetected coeliac disease have a slight tendency towards low bone density and measurements in keeping with mildly subnormal nutritional status.35,36,37

Analysis of a population based cohort from Cambridge, UK, showed that there were some negative health effects of undetected coeliac disease, for example mild anaemia and osteoporosis.10 However, the study findings implied a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease from the observations of lower body mass index, lower blood pressure, and lower serum cholesterol in people with undetected coeliac disease. This effect, of potentially large impact, requires confirmation and further epidemiological assessment.

Impact of clinically diagnosed coeliac disease

Osteoporosis and fracture

As a consequence of osteoporosis there may be an increased risk of fracture in people with coeliac disease. Due to this perceived increase in fracture risk, some groups (including the British Society of Gastroenterology) have recommended screening and surveillance of people with coeliac disease for decreased bone mineral density in order to implement treatment with bisphosphonates or hormone replacement therapy.25,38,39 Some estimates of the excess fracture risk experienced by people with coeliac disease in comparison with the general population are available. Vasquez et al compared the fracture experience of 165 patients with that of controls with functional gastrointestinal disorders and found a threefold increase in overall fracture risk.40 A subsequent study from the same group found that the increase in fracture experience was confined to patients with coeliac disease presenting with “classical malabsorption” (odds ratio 5) compared with matched controls.41 Fickling et al reported a “relative risk” of fracture of 7 based on a survey of 75 patients and matched controls selected from patients who had attended for bone densitometry.42

Key recent advances and unanswered questions in the epidemiology of coeliac disease

Advances

The prevalence of undetected coeliac disease in the general population is approximately 1%.

Timing of gluten introduction and cessation of breast feeding influences the risk of developing coeliac disease.

The risks of adverse consequences in people with clinically diagnosed coeliac disease such as fracture, malignancy, mortality, and low fertility rates are modest.

Oats appear generally safe as part of the gluten free diet.

Questions

What is the natural history of undetected coeliac disease?

What is the true disease burden and cost of coeliac disease?

Should we screen the general population (or selected groups at apparent increased risk) for undetected coeliac disease?

More recent data from larger series however point to a much smaller increased fracture risk in coeliac disease. Both Vestergaard and Mosekilde, in a database study of 1021 hospital diagnosed subjects with coeliac disease, and Thomason et al, using a mailed questionnaire survey of 244 cases, found no increase in the overall fracture risk compared with the general population but with wide confidence limits.43,44 West et al, who used a population based cohort study involving 4732 people with coeliac disease, showed that overall there was a small increased risk of fracture in those with coeliac disease.45 The risks of “osteoporotic” fracture such as hip (rate ratio 1.9), ulna/radius (rate ratio 1.8), and vertebral (rate ratio 1.5; J West unpublished data) were higher than the overall risk but were, at most, moderate. Translating these data into follow up of 1000 people with coeliac disease for one year compared with a similar group from the general population means only one extra hip fracture during the year.

Some groups have suggested that all newly diagnosed adults with coeliac disease should be screened for osteoporosis, using DEXA scanning, either at diagnosis or following one year of treatment with a gluten free diet.25,38,39 Overall the current research data would suggest that more studies are needed on the safety, efficacy, and cost effectiveness of such screening programmes before they are universally recommended.

Malignancy and mortality

Early studies of the risk of malignancy and mortality in patients with coeliac disease suggested a twofold increase in mortality rate, and greatly increased risks of lymphoproliferative malignancies. Most studies have been small or not population based, and their findings probably do not reflect the risks in contemporary coeliac disease.46,47,48,49,50 More recent data from Sweden based on cases from hospital inpatient registers have suggested more modest increases in the risks but still found that people with coeliac disease were at excess risk of certain malignancies and death.51,52 Although large and population based, these studies were dependent on hospital admission of the index case for ascertainment, and thus may be biased towards overestimation of the risks. A further study from Derby, UK, showed that for a large cohort of people with coeliac disease followed up for nearly 25 years there was no overall increase in malignancy risk.53 In this study, the absolute risk of non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma was 1 in 1421 person years and for small bowel lymphoma 1 in 5684 person years, indicating the rarity of the occurrence of such malignancies. The majority of other studies have found overall increased risks for malignancy or mortality of twofold or greater46,47,48,49,50 but these studies have been in cohorts of people with coeliac disease diagnosed and followed up some time ago, or from specialist referral centres.

Interestingly, four studies have suggested a decrease in the risk of breast cancer in people with coeliac disease, the reasons for which are not clear.49,52,53,54

Recent findings from the UK General Practice Research Database are more consistent with the modest risks observed in Sweden.54 In this study, people with diagnosed coeliac disease had modest increases in the relative and absolute risk of malignancy and mortality. Most of the excess risk occurred in the first year after diagnosis and suggest that in treated coeliac disease the excess risk of cancer and shortened life expectancy are low.

Fertility

Previous research has suggested that coeliac disease, along with other chronic inflammatory diseases, may be associated with reduced fertility and increased risk of adverse pregnancy related events.55,56,57,58,59 Some have accepted that infertility is indeed a complication of coeliac disease and if true this is of importance to both women with coeliac disease and to those who manage their care.60 Reported associations between coeliac disease and a higher incidence of termination, miscarriage, and having babies with low birth weight or intrauterine growth retardation, have also raised concern.3,58,61,62,63,64,65

Recent work compared the fertility experience of 1521 UK women with coeliac disease to women in the general population using the General Practice Research Database.66 Women with coeliac disease had similar fertility rates to the general female population but tended to have babies at a later age. As the patterns of later fertility for the untreated group versus the treated group were similar, when restricted to incident patients, it seems unlikely that the cause of this later fertility is due to the degree of disease activity. An increased proportion of caesarean section deliveries in women with coeliac disease was present in the older age groups, again likely due to older maternal age rather than a disease effect. These results indicate that the risks of adverse pregnancy related outcomes for women with coeliac disease are not markedly raised.

These findings are in contrast with those recently reported by Ludvigsson et al who examined adverse fetal outcome in a large population based cohort study.67 They found that women who had undiagnosed coeliac disease at the time of delivery were more likely to have a preterm birth, caesarean section, or have an offspring with intrauterine growth retardation, low birth weight, or very low birth weight. In contrast, maternal coeliac disease diagnosed before birth was not associated with adverse fetal outcomes. While they adjusted their analyses for various factors, the proportion of mothers with undiagnosed disease in the later period (1996–2001) was small, so their findings may not be generalisable to contemporary undiagnosed coeliac disease. For example, people with a more serious illness may have remained undiagnosed for longer prior to the development (and availability) of endoscopic biopsies and serological markers.

Clinical implications of basic science advances

Steps in coeliac disease pathogenesis

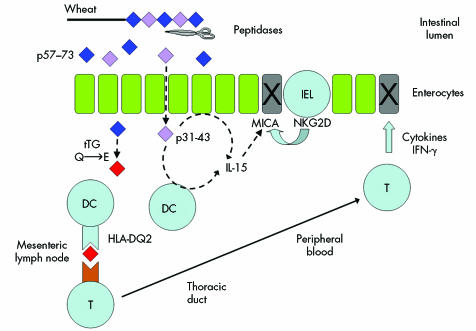

Our understanding of the key steps underlying the intestinal inflammatory response to coeliac disease has increased dramatically in recent years. These steps include: (i) a (putative) direct response of the epithelium via the innate immune system to toxic proteins in wheat gluten, (ii) modification of wheat gluten proteins by tissue transglutaminase, (iii) role of HLA‐DQ2 in presenting toxic wheat proteins to T cells, and (iv) identification of key toxic protein sequences in wheat (fig 3). These advances have introduced the possibility of novel therapeutics (distinct from the gluten free diet) to treat coeliac disease.

Figure 3 Underlying mechanisms in coeliac disease pathogenesis. Wheat gluten is partially digested but key toxic sequences are resistant to intestinal proteases. One gluten peptide (p31‐43/49) may directly induce interleukin 15 (IL‐15) production from enterocytes and dendritic cells but precise details remain unclear. IL‐15 upregulates MICA, a stress molecule on enterocytes. Another gluten peptide (p57‐73) is deamidated by tissue transglutaminase and is presented to T cells by HLA‐DQ2 on antigen presenting cells. The initial triggering event occurs in the mesenteric lymph nodes but the importance of presentation in the mucosa is uncertain. Epithelial cytotoxicity occurs via at least two mechanisms: cytokine release (especially interferon γ (IFN‐γ)) by antigen specific T cells and directly by intraepithelial lymphocytes via MICA‐NKG2D interaction.

The work of Dicke and Frazer in the 1950s identified the protein component of wheat (gluten) as the toxic fraction. Toxic sequences are now identified in both gliadin and glutenin components as well as similar proteins in rye and barley. Cereals are polyploid in nature which combined with the large allelic variation present in all gluten genes makes even gluten from a single wheat variety a complex mixture. However, the general structure of the protein families and the relevance of the high proline(P) and glutamine(Q) content to human coeliac disease is now understood. Interestingly, the fact that many gliadin peptides possess bulky hydrophobic amino acids followed by proline blocks the activity of intestinal peptidases such as pepsin and chymotrypsin.68,69 Thus gluten peptides able to stimulate T cells (such as a recently described 33mer sequence) are resistant to degradation by all gastric, pancreatic, and intestinal brush border membrane proteases in the human intestine.70

Several recent reports have suggested that one of the first events in coeliac disease pathogenesis may be a direct effect of certain wheat peptides, distinct from those recognised by T cells, on the intestinal epithelium. One such peptide, wheat A‐gliadin p31‐43 (LGQQQPFPPQQPY) or p31‐49 induces changes associated with coeliac disease on intraduodenal administration,71 and in vitro in biopsy based studies.72,73 Changes were observed in patients within four hours, which is surprisingly rapid for a purely T cell mediated response. More recent work demonstrated that this peptide appears to induce interleukin 15, a key cytokine involved in T cell activation, and preincubation with the peptide permits later activation of biopsies by known T cell stimulatory wheat gluten sequences.72 Interleukin 15 also appears to induce expression of a stress molecule, MICA, on enterocytes and upregulates NKG2D receptors on intraepithelial lymphocytes. The interaction between enterocyte MICA and lymphocyte NKG2D results in direct enterocyte killing, and is likely to be one way villous atrophy occurs.73,74 Direct effects of gliadin on enterocytes may also increase intestinal permeability through release of zonulin and effects on intracellular tight junctions.75 Surface tissue transglutaminase may have a role in innate immune signalling by p31‐43 in coeliac disease.76 More precise details of these mechanisms remain to be elucidated. It is not known whether enterocytes, macrophages/dendritic cells, or another cell type in the small intestinal mucosa are directly activated by p31‐43/49, what receptor mechanism is involved, and why these events should be coeliac disease specific.

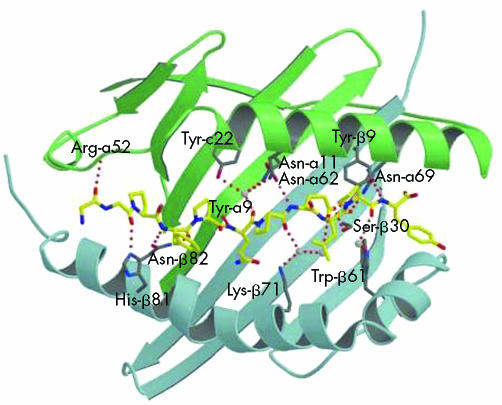

Involvement of the human leucocyte antigen region (HLA) in coeliac disease was first suggested by serotype based association studies. More detailed analyses at the genetic level implicated HLA‐DQ2.77 Nearly all patients with coeliac disease possess either the HLA‐DQ2 heterodimer (encoded by DQA1*05 and DQB1*02) or HLA‐DQ8 (DQA1*03 and DQB1*0302) compared with approximately one third of Caucasian populations. A European study of 1008 coeliac patients found that 90% possessed genetic variants encoding the HLA‐DQ2 heterodimer (in various forms), 4% with partial HLA‐DQ2 (DQB1*02 without DQA1*05), 2% with partial HLA‐DQ2 (DQA1*05 without DQB1*02), and 6% HLA‐DQ8 without DQ‐278. Our current understanding of coeliac disease susceptibility implies possession of HLA‐DQ2 is necessary but not sufficient for coeliac disease development (as it is also possessed by 30% of the healthy Caucasian population). Nevertheless, genetic testing for HLA‐DQ is a useful cost effective test to exclude coeliac disease in individuals already following a gluten free diet. Interestingly, HLA‐DQ2 can be encoded in several different ways, leading to variation in the proportion of HLA‐DQ2 molecules present.79 Individuals homozygous for HLA‐DQB1*02 appear to be at highest risk of coeliac disease. The functional role of HLA‐DQ2 in coeliac disease is now clearly defined and explains the genetic association. Cells able to present toxic gluten peptides to T cells do so via HLA‐DQ2. Recent work has even identified the crystal structure and kinetics of dominant wheat gluten peptide binding to HLA‐DQ2 (fig 4).80,81

Figure 4 Crystal structure of immunodominant wheat gluten peptide binding to HLA‐DQ2. Putative hydrogen bonding network (red dashes) between DQ2 (α, β chains in green, blue) and α1‐gliadin epitope (amino acids PFPQPELPY, underlining shows tissue transglutaminase modified residue) are shown. DQ2 side chains engaged in hydrogen bonding are shown in grey. Atoms depicted in yellow (carbon), blue (nitrogen), and red (oxygen). Reprinted from Kim et al with permission80 (copyright 2004 National Academy of Sciences, USA).

The function of the HLA class II molecule—to present short peptides to T cells—implied that specific dietary wheat, rye, and barley peptides might be presented via HLA‐DQ2 in coeliac disease. Although intestinal T cells specific for wheat gluten were first identified in 1993,82 it was only with the discovery that intestinal T cells specifically recognise deamidated gluten peptides that more precise identification was possible.83 HLA‐DQ2 preferentially binds peptides with negatively charged amino acids present in key positions. Tissue transglutaminase (the target of the antiendomysial autoantibody response in coeliac disease) plays a key role in conversion of specific glutamine residues to glutamate in the intestinal mucosa, generating negatively charged amino acids better able to bind HLA‐DQ2.83 In the intestine, tissue transglutaminase is found just below the epithelium and in the brush border. Deamidation of glutamine residues within a protein sequence is biochemically predictable.84 It remains unclear however why antitissue transglutaminase antibodies are such specific and sensitive indicators of coeliac disease. Such antibodies may recognise transglutaminase‐wheat peptide crosslinked complexes85 although whether these have a primary role in disease pathogenesis or are a bystander secondary phenomenon is uncertain.

Identification of the key dietary wheat, rye, and barley peptides presented by T cells is critical for immunologically based therapies aimed at inducing tolerance and attempts at genetic modification of grains to render them non‐toxic. Initial presentation of dietary antigen to naïve T cells occurs in the mesenteric lymph nodes; these cells recirculate in peripheral blood via the thoracic duct, and home back to the intestine via specific cell adhesion molecules (fig 3). The majority of studies have focused on intestinal T cell lines and clones generated in vitro from small bowel biopsy samples. These methods have identified a large number of different HLA‐DQ2 restricted peptides from wheat α/β, γ, and ω gliadins and low molecular weight glutenins,68,86,87,88 sequences from rye and barley homologous to wheat peptides,89 and a sequence from oat avenins.89,90 However, whether such intestinal biopsy derived T cells generated artificially over many weeks are truly representative of responses in vivo has been unclear. Furthermore, consistency of responses across coeliac individuals has been variable. Arentz‐Hansen et al found intestinal T cells responsive to one of two overlapping peptides (QLQPFPQPELPY, PQPELPYPQPELPY) in all 17 HLA‐DQ2 coeliac subjects.87 In contrast, another study found poor consistency among 20 coeliac subjects.86 Methodological differences are likely to explain these variations but raise concerns as to the relevance of identified peptides to human disease in vivo.

Key recent advances and unanswered questions in mechanisms of coeliac disease pathogenesis

Advances

HLA‐DQ2 presents T cell stimulatory wheat gluten peptides.

Tissue transglutaminase modifies gluten peptides to generate more potent T cell stimulatory sequences.

Immunodominant T cell stimulatory gluten peptides defined.

Gluten peptides may also activate the innate immune system.

Resistance of toxic gluten peptides to degradation in the intestine.

Questions

Mechanisms underlying innate immune system activation by gliadin peptides.

Does the autoantibody response to tissue transglutaminase have a pathogenic role?

How gluten peptides enter the intestinal mucosa, and mechanisms of presentation to T cells.

Identification of further genetic (and environmental) factors predisposing to coeliac disease.

Factors regulating oral tolerance and suppression of immune responses to gluten.

Can a good animal model of coeliac disease be generated, particularly to study novel therapeutics?

An alternative strategy has been developed by Anderson et al, and uses peripheral blood from coeliac subjects drawn after oral gluten challenge.91 In individuals following a gluten free diet for a minimum of two weeks, peripheral blood T cell responses can be reliably detected within a window of three days to two weeks after in vivo oral bread challenge.92 That these T cells are HLA‐DQ2 restricted and express gut homing molecules strongly suggests the assay is detecting freshly activated cells recirculating via the thoracic duct (fig 3) and might provide a more accurate picture of the in vivo response to wheat gluten. This method has been used with a library of peptides to “map” toxic wheat sequences,91 and due to the high throughput nature offers the possibility of exhaustive screening of all grains for potentially toxic peptide sequences in coeliac disease.93 Interestingly, results from both peripheral blood and intestinal T cell clone methods identified the same key sequence (PQPELPY) later shown to directly bind to HLA‐DQ2 (fig 4).80,87,91 Responses to this sequence were found in the peripheral blood of 50/57 tested coeliac subjects (but not healthy controls) after in vivo gluten challenge and represented 50% of the total wheat gliadin response.92 Other work has shown that in vivo intraduodenal administration of a peptide containing this sequence can exacerbate coeliac disease.94 Further assessment of other wheat, rye, and barley sequences will be necessary but it would appear that a few key “dominant” peptide epitopes critical for coeliac disease development can be identified with promise for immunotherapies and modified grains.

Diagnostics and therapeutics

Which serological test?

In the 1980s, Chorzelski et al described the production of antiendomysial antibodies in people with dermatitis herpetiformis and coeliac disease.95 Endomysium is a connective tissue protein found in the collagenous matrix of human and monkey oesophagus. Antibodies to endomysium can be measured in serum with the use of indirect immunofluorescence.95 The autoantigen recognised by endomysial antibody is tissue transglutaminase, whose role in the pathogenesis of coeliac disease is described above. The IgA antiendomysial antibody test can use either monkey oesophagus or human umbilical cord as substrate and its diagnostic utility has been shown to be very good, with specificity estimated at 99% and sensitivity over 90%.96 However, the test is labour intensive and qualitative so requires money, time, and expertise to perform. This has led to the development of enzyme linked immunoabsorbent assay based tests for measurement of IgA tissue transglutaminase antibody levels that are of comparable sensitivity and specificity to the antiendomysial antibody test.97,98,99,100 Measuring tissue transglutaminase antibody levels is quicker, easier, and quantitative, so has clear advantages over the antiendomysial antibody test.26 Both tests have superseded the use of antigliadin antibodies, which although of some use101 have subsequently been shown to have inferior diagnostic accuracy102 with sensitivity as low as 76%. Further improvements in diagnostic accuracy of the antitissue transglutaminase antibody test have been made by use of recombinant human rather than guinea pig transglutaminase in the assay kits.103 Standardisation and quality control of diagnostic tests for coeliac disease is an important issue.

Coeliac disease has an association with IgA deficiency so it is possible to incorrectly label a person as not having coeliac disease in such cases, particularly when using the IgA dependent immunofluorescence endomysial antibody test.104 Recently, improvements in techniques for measuring tissue transglutaminase have allowed simultaneous measurement of low serum IgA in the same assay.105 Although serology appears very sensitive at detecting people with coeliac disease, it is intriguing that some cases of apparent seronegative coeliac disease occur, even in the presence of normal serum IgA. One explanation is that antibody expression is lower in milder mucosal lesions although other possibilities have been proposed.106

Oats and the gluten free diet

Historically there was concern that oats may not be safe in coeliac disease. However, the trial by Janatuinen et al showing no adverse effects after 6–12 months of dietary oats in patients with coeliac disease was reassuring and has been confirmed by numerous recent studies.107 Indeed, little effect has been observed on small intestinal mucosal biopsies and in general oats have been well tolerated.108,109,110 This appears true for both adults and children. Janatuinen et al have also reported five year follow up data confirming their initial findings of no obvious harm.111 While there have been concerns about the quality of oats in some countries112,113 (with respect to gluten contamination) it seems that in order to diversify the gluten free diet and hence encourage compliance, oat containing foods should be encouraged for most patients. However, a handful of patients have been reported who do appear to show both clinical and immunological responses to a pure oat product.90,114

Novel therapeutic possibilities

The finding that one of the key T cell stimulatory peptides in coeliac disease is resistant to breakdown by intestinal proteases has created interest in digesting these peptides by dietary supplements to remove toxicity. Bacterial prolyl‐endopeptidases can degrade the 33mer T cell stimulatory peptide described by Shan et al, and have been commercially produced.70,115 Very high concentrations of prolyl‐endopeptidase have been shown in biopsy studies to reduce the amount of immunostimulatory gliadin peptides (both innate immune and T cell activating) reaching the mucosa.116 Whether these therapies will work as dietary supplements awaits human in vivo trials. Such supplements may be able to prevent inadvertent low level gluten exposure even if a full gluten containing diet cannot be achieved.

Attempts to induce immune tolerance are now being attempted in several diseases. For example, treatment with anti‐CD3 antibodies (targeted against the T cell receptor) in type 1 diabetes induces transferable T cell mediated tolerance involving the CD4+CD25+ regulatory subset mediated by transforming growth factor β.117,118 More targeted therapies aimed at inducing antigen specific tolerance are being developed for type I diabetes and such strategies should be possible in coeliac disease.119 Identification of dominant wheat protein epitopes in coeliac disease has been a key step towards such therapies.

Alternatively, it may be possible to generate wheat (and other cereals) with absent or reduced immunogenicity by selective breeding or genetic modification. Certain varieties of ancient wheats appear to have fewer toxic T cell sequences.120,121 Whether it will be possible to breed commercially useful crops, with the necessary properties (for example, baking qualities) and overcome all T cell stimulatory sequences (including in glutenins, and for DQ8 coeliac disease) remains highly uncertain.

Finally, other strategies are also suggested by advances in our understanding of coeliac disease pathogenesis. Blocking tissue transglutaminase mediated deamidation of gluten peptides, zonulin mediated increases in intestinal permeability, HLA‐DQ2 peptide interactions, or MICA‐NKG2D interactions are all possible therapeutic targets although they may be limited by toxicity. Methods have also been developed to sensitively screen for T cell stimulatory peptides in foods to better guarantee food safety for coeliac disease patients.122

Conclusions

Coeliac disease is evidently much more common in Caucasian populations than previously thought. Several large population based studies estimate the prevalence at ∼1%. Further well conducted population based studies suggest that the overall risks of various morbidities and mortality in treated coeliac disease (as diagnosed in current UK practice) are relatively minor. From an individual perspective, both the clinicians that manage their care and coeliac disease patients now have reasonably precise information to inform them of the actual risks to their health in terms of a range of morbidities and life expectancy. Published guidelines on the management of coeliac disease are now available although some need updating in the light of these recent studies.25,28,38,123,124 Clearly some individuals may be at higher risk of adverse events than others, and identifying those people who might benefit from further intervention in addition to a gluten free diet is a clinical challenge needing further research. Equally, others are at low risk of adverse events, questioning the need for ongoing hospital follow up.

Advances in understanding coeliac disease pathogenesis at a basic science level have opened up prospects for novel diagnostics and therapeutics, and made coeliac disease one of the best understood autoimmune disorders.

Conflict of interest: declared (the declaration can be viewed on the Gut website at http://www.gutjnl.com/supplemental).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof Richard Logan, Dr Geoff Holmes, and Dr Robert Anderson for comments on the manuscript. DAvH is funded by a Wellcome Trust Clinician Scientist Fellowship and Coeliac UK.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: declared (the declaration can be viewed on the Gut website at http://www.gutjnl.com/supplemental).

References

- 1.Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T.et al Prevalence of celiac disease in at‐risk and not‐at‐risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med 2003163286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catassi C, Ratsch I M, Fabiani E.et al Coeliac disease in the year 2000: exploring the iceberg. Lancet 1994343200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meloni G, Dore A, Fanciulli G.et al Subclinical coeliac disease in schoolchildren from northern Sardinia. Lancet 199935337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bingley P J, Williams A J, Norcross A J.et al Undiagnosed coeliac disease at age seven: population based prospective birth cohort study. BMJ 2004328322–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maki M, Mustalahti K, Kokkonen J.et al Prevalence of celiac disease among children in Finland. N Engl J Med 20033482517–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catassi C, Ratsch I M, Gandolfi L.et al Why is coeliac disease endemic in the people of the Sahara? Lancet 1999354647–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston S D, Watson R G, McMillan S A.et al Prevalence of coeliac disease in Northern Ireland. Lancet 19973501370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivarsson A, Persson L A, Juto P.et al High prevalence of undiagnosed coeliac disease in adults: a Swedish population‐based study. J Intern Med 199924563–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Couignoux S, Ocmant A, Cottel D.et al Prevalence of adult coeliac disease in Northern France. Gut 200047A196 [Google Scholar]

- 10.West J, Logan R F, Hill P G.et al Seroprevalence, correlates, and characteristics of undetected coeliac disease in England. Gut 200352960–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collin P, Reunala T, Rasmussen M.et al High incidence and prevalence of adult coeliac disease. Augmented diagnostic approach. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997321129–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bode S, Gudmand‐Hoyer E. Incidence and prevalence of adult coeliac disease within a defined geographic area in Denmark. Scand J Gastroenterol 199631694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray J A, van Dyke C, Plevak M F.et al Trends in the identification and clinical features of celiac disease in a North American Community, 1950–2001. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Logan R F, Rifkind E A, Busuttil A.et al Prevalence and “incidence” of celiac disease in Edinburgh and the Lothian region of Scotland. Gastroenterology 198690334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West J, Palmer B P.et al Trends in clinical presentation of adult coeliac disease: a 25 year prospective study. Gut 200148(suppl I)A78 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens F M, Egan‐Mitchell B, Cryan E.et al Decreasing incidence of coeliac disease. Arch Dis Child 198762465–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dossetor J F, Gibson A A, McNeish A S. Childhood coeliac disease is disappearing. Lancet 19811322–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Littlewood J M, Crollick A J, Richards I D G. Childhood coeliac disease is disappearing. Lancet 1980ii1359 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maki M, Kallonen K, Lahdeaho M L.et al Changing pattern of childhood coeliac disease in Finland. Acta Paediatr Scand 198877408–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dahan S, Slater P E, Cooper M.et al Coeliac disease in the Rehovot‐Ashdod region of Israel: incidence and ethnic distribution. J Epidemiol Comm Health 19843858–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivarsson A, Persson L A, Nystrom L.et al Epidemic of coeliac disease in Swedish children. Acta Paediatr 200089165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivarsson A. The Swedish epidemic of coeliac disease explored using an epidemiological approach—some lessons to be learnt. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 200519425–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.George E K, Mearin M L, Franken H C.et al Twenty years of childhood coeliac disease in The Netherlands: a rapidly increasing incidence? Gut 19974061–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawkes N D, Swift G L, Smith P M.et al Incidence and presentation of coeliac disease in South Glamorgan. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 200012345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: celiac sprue Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1522–1525. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fasano A, Catassi C. Current approaches to diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease: an evolving spectrum. Gastroenterology 2001120636–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feighery C. Fortnightly review: coeliac disease. BMJ 1999319236–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciclitira P J, King A L, Fraser J S. AGA technical review on celiac sprue. American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 20011201526–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maki M, Collin P. Coeliac disease. Lancet 19973491755–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bode S, Gudmand‐Hoyer E. Symptoms and haematologic features in consecutive adult coeliac patients. Scand J Gastroenterol 19963154–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Logan R F, Tucker G, Rifkind E A.et al Changes in clinical features of coeliac disease in adults in Edinburgh and the Lothians 1960–79. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 198328695–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanders D S, Hurlstone D P, Stokes R O.et al Changing face of adult coeliac disease: experience of a single university hospital in South Yorkshire. Postgrad Med J 20027831–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lo W, Sano K, Lebwohl B.et al Changing presentation of adult celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci 200348395–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hin H, Bird G, Fisher P.et al Coeliac disease in primary care: case finding study. BMJ 1999318164–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corazza G R, Di Sario A, Cecchetti L.et al Influence of pattern of clinical presentation and of gluten‐free diet on bone mass and metabolism in adult coeliac disease. Bone 199618525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corazza G R, Di Sario A, Sacco G.et al Subclinical coeliac disease: an anthropometric assessment. J Intern Med 1994236183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mustalahti K, Collin P, Sievanen H.et al Osteopenia in patients with clinically silent coeliac disease warrants screening. Lancet 1999354744–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scott E M, Gaywood I, Scott B B. Guidelines for osteoporosis in coeliac disease and inflammatory bowel disease. British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut 200046(suppl 1)i1–i8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernstein C N, Leslie W D. The pathophysiology of bone disease in gastrointestinal disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 200315857–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vasquez H, Mazure R, Gonzalez D.et al Risk of fractures in celiac disease patients: a cross‐sectional, case‐control study. Am J Gastroenterol 200095183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moreno M L, Vazquez H, Mazure R.et al Stratification of bone fracture risk in patients with celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 20042127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fickling W E, McFarlane X A, Bhalla A K.et al The clinical impact of metabolic bone disease in coeliac disease. Postgrad Med J 20017733–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomason K, West J, Logan R F.et al Fracture experience of patients with coeliac disease: a population based survey. Gut 200352518–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L. Fracture risk in patients with celiac disease, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis: a nationwide follow‐up study of 16,416 patients in Denmark. Am J Epidemiol 20021561–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.West J, Logan R F, Card T R.et al Fracture risk in people with celiac disease: a population‐based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2003125429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corrao G, Corazza G R, Bagnardi V.et al Mortality in patients with coeliac disease and their relatives: a cohort study. Lancet 2001358356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holmes G K, Prior P, Lane M R.et al Malignancy in coeliac disease—effect of a gluten free diet. Gut 198930333–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cooper B T, Holmes G K, Ferguson R.et al Celiac disease and malignancy. Medicine (Baltimore) 198059249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Logan R F, Rifkind E A, Turner I D.et al Mortality in celiac disease. Gastroenterology 198997265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cottone M, Termini A, Oliva L.et al Mortality and causes of death in celiac disease in a Mediterranean area. Dig Dis Sci 1999442538–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peters U, Askling J, Gridley G.et al Causes of death in patients with celiac disease in a population‐based Swedish cohort. Arch Intern Med 20031631566–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Askling J, Linet M, Gridley G.et al Cancer incidence in a population‐based cohort of individuals hospitalized with celiac disease or dermatitis herpetiformis. Gastroenterology 20021231428–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Card T R, West J, Holmes G K. Risk of malignancy in diagnosed coeliac disease: a 24‐year prospective, population‐based, cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 200420769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.West J, Logan R F, Smith C J.et al Malignancy and mortality in people with coeliac disease: population based cohort study. BMJ 2004329716–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alstead E M, Nelson‐Piercy C. Inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy. Gut 200352159–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buchel E, Van Steenbergen W, Nevens F.et al Improvement of autoimmune hepatitis during pregnancy followed by flare‐up after delivery. Am J Gastroenterol 2002973160–3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dominitz J A, Young J C, Boyko E J. Outcomes of infants born to mothers with inflammatory bowel disease: a population‐based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 200297641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rostami K, Steegers E A, Wong W Y.et al Coeliac disease and reproductive disorders: a neglected association. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 200196146–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wood S L, Jick H, Sauve R. The risk of stillbirth in pregnancies before and after the onset of diabetes. Diabet Med 200320703–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Green P H, Jabri B. Coeliac disease. Lancet 2003362383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smecuol E, Maurino E, Vazquez H.et al Gynaecological and obstetric disorders in coeliac disease: frequent clinical onset during pregnancy or the puerperium. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996863–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Norgard B, Fonager K, Sorensen H T.et al Birth outcomes of women with celiac disease: a nationwide historical cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 1999942435–2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ciacci C, Cirillo M, Auriemma G.et al Celiac disease and pregnancy outcome. Am J Gastroenterol 199691718–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sher K S, Mayberry J F. Female fertility, obstetric and gynaecological history in coeliac disease: a case control study. Acta Paediatr Suppl 199641276–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martinelli P, Troncone R, Paparo F.et al Coeliac disease and unfavourable outcome of pregnancy. Gut 200046332–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tata L J, Card T R, Logan R F.et al Fertility and pregnancy‐related events in women with celiac disease: a population‐based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2005128849–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ludvigsson J F, Montgomery S M, Ekbom A. Celiac disease and risk of adverse fetal outcome: a population‐based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2005129454–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arentz‐Hansen H, McAdam S N, Molberg O.et al Celiac lesion T cells recognize epitopes that cluster in regions of gliadins rich in proline residues. Gastroenterology 2002123803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hausch F, Shan L, Santiago N A.et al Intestinal digestive resistance of immunodominant gliadin peptides. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2002283G996–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shan L, Molberg O, Parrot I.et al Structural basis for gluten intolerance in celiac sprue. Science 20022972275–2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sturgess R, Day P, Ellis H J.et al Wheat peptide challenge in coeliac disease. Lancet 1994343758–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maiuri L, Ciacci C, Ricciardelli I.et al Association between innate response to gliadin and activation of pathogenic T cells in coeliac disease. Lancet 200336230–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hue S, Mention J J, Monteiro R C.et al A direct role for NKG2D/MICA interaction in villous atrophy during celiac disease. Immunity 200421367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meresse B, Chen Z, Ciszewski C.et al Coordinated induction by IL15 of a TCR‐independent NKG2D signaling pathway converts CTL into lymphokine‐activated killer cells in celiac disease. Immunity 200421357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clemente M G, De Virgiliis S, Kang J S.et al Early effects of gliadin on enterocyte intracellular signalling involved in intestinal barrier function. Gut 200352218–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maiuri L, Ciacci C, Ricciardelli I.et al Unexpected role of surface transglutaminase type II in celiac disease. Gastroenterology 20051291400–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sollid L M, Markussen G, Ek J.et al Evidence for a primary association of celiac disease to a particular HLA‐DQ alpha/beta heterodimer. J Exp Med 1989169345–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Karell K, Louka A S, Moodie S J.et al HLA types in celiac disease patients not carrying the DQA1*05‐DQB1*02 (DQ2) heterodimer: results from the European Genetics Cluster on Celiac Disease. Hum Immunol 200364469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Heel D A, Hunt K, Greco L.et al Genetics in coeliac disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 200519323–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim C Y, Quarsten H, Bergseng E.et al Structural basis for HLA‐DQ2‐mediated presentation of gluten epitopes in celiac disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 20041014175–4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xia J, Sollid L M, Khosla C. Equilibrium and kinetic analysis of the unusual binding behavior of a highly immunogenic gluten peptide to HLA‐DQ2. Biochemistry 2005444442–4449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lundin K E, Scott H, Hansen T.et al Gliadin‐specific, HLA‐DQ (alpha 1*0501,beta 1*0201) restricted T cells isolated from the small intestinal mucosa of celiac disease patients. J Exp Med 1993178187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Molberg O, McAdam S N, Korner R.et al Tissue transglutaminase selectively modifies gliadin peptides that are recognized by gut‐derived T cells in celiac disease. Nat Med 19984713–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vader L W, de Ru A, van der Wal Y.et al Specificity of tissue transglutaminase explains cereal toxicity in celiac disease. J Exp Med 2002195643–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fleckenstein B, Qiao S W, Larsen M R.et al Molecular characterization of covalent complexes between tissue transglutaminase and gliadin peptides. J Biol Chem 200427917607–17616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vader W, Kooy Y, Van Veelen P.et al The gluten response in children with celiac disease is directed toward multiple gliadin and glutenin peptides. Gastroenterology 20021221729–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Arentz‐Hansen H, Korner R, Molberg O.et al The intestinal T cell response to alpha‐gliadin in adult celiac disease is focused on a single deamidated glutamine targeted by tissue transglutaminase. J Exp Med 2000191603–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sjostrom H, Lundin K E, Molberg O.et al Identification of a gliadin T‐cell epitope in coeliac disease: general importance of gliadin deamidation for intestinal T‐cell recognition. Scand J Immunol 199848111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vader L W, Stepniak D T, Bunnik E M.et al Characterization of cereal toxicity for celiac disease patients based on protein homology in grains. Gastroenterology 20031251105–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Arentz‐Hansen H, Fleckenstein B, Molberg O.et al The molecular basis for oat intolerance in patients with celiac disease. PLoS Med 20041e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Anderson R P, Degano P, Godkin A J.et al In vivo antigen challenge in celiac disease identifies a single transglutaminase‐modified peptide as the dominant A‐gliadin T‐cell epitope. Nat Med 20006337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Anderson R P, van Heel D A, Tye‐Din J A.et al T cells in peripheral blood after gluten challenge in coeliac disease. Gut 2005541217–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Beissbarth T, Tye‐Din J A, Smyth G K.et al A systematic approach for comprehensive T‐cell epitope discovery using peptide libraries. Bioinformatics 200521i29–i37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fraser J S, Engel W, Ellis H J.et al Coeliac disease: in vivo toxicity of the putative immunodominant epitope. Gut 2003521698–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chorzelski T P, Beutner E H, Sulej J.et al IgA anti‐endomysium antibody. A new immunological marker of dermatitis herpetiformis and coeliac disease. Br J Dermatol 1984111395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.James M W, Scott B B. Endomysial antibody in the diagnosis and management of coeliac disease. Postgrad Med J 200076466–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Burgin‐Wolff A, Dahlbom I, Hadziselimovic F.et al Antibodies against human tissue transglutaminase and endomysium in diagnosing and monitoring coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 200237685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Horvath K, Hill I D. Anti‐tissue transglutaminase antibody as the first line screening for celiac disease: good‐bye antigliadin tests? Am J Gastroenterol 2002972702–2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dieterich W, Laag E, Schopper H.et al Autoantibodies to tissue transglutaminase as predictors of celiac disease. Gastroenterology 19981151317–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sulkanen S, Halttunen T, Laurila K.et al Tissue transglutaminase autoantibody enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay in detecting celiac disease. Gastroenterology 19981151322–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hill P G, Thompson S P, Holmes G K. IgA anti‐gliadin antibodies in adult celiac disease. Clin Chem 199137647–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.West J, Lloyd C A, Hill P G.et al IgA‐antitissue transglutaminase: validation of a commercial assay for diagnosing coeliac disease. Clin Lab 200248241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wong R C, Wilson R J, Steele R H.et al A comparison of 13 guinea pig and human anti‐tissue transglutaminase antibody ELISA kits. J Clin Pathol 200255488–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cataldo F, Marino V, Bottaro G.et al Celiac disease and selective immunoglobulin A deficiency. J Pediatr 1997131306–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hill P G, Forsyth J M, Semeraro D.et al IgA antibodies to human tissue transglutaminase: audit of routine practice confirms high diagnostic accuracy. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004391078–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Green P H, Rostami K, Marsh M N. Diagnosis of coeliac disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 200519389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Janatuinen E K, Pikkarainen P H, Kemppainen T A.et al A comparison of diets with and without oats in adults with celiac disease. N Engl J Med 19953331033–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hoffenberg E J, Haas J, Drescher A.et al A trial of oats in children with newly diagnosed celiac disease. J Pediatr 2000137361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hogberg L, Laurin P, Falth‐Magnusson K.et al Oats to children with newly diagnosed coeliac disease: a randomised double blind study. Gut 200453649–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Picarelli A, Di Tola M, Sabbatella L.et al Immunologic evidence of no harmful effect of oats in celiac disease. Am J Clin Nutr 200174137–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Janatuinen E K, Kemppainen T A, Julkunen R J.et al No harm from five year ingestion of oats in coeliac disease. Gut 200250332–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kupper C. Dietary guidelines and implementation for celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2005128S121–S127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Thompson T. Gluten contamination of commercial oat products in the United States. N Engl J Med 20043512021–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lundin K E, Nilsen E M, Scott H G.et al Oats induced villous atrophy in coeliac disease. Gut 2003521649–1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Shan L, Mathews I I, Khosla C. Structural and mechanistic analysis of two prolyl endopeptidases: role of interdomain dynamics in catalysis and specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 20051023599–3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Matysiak‐Budnik T, Candalh C, Cellier C.et al Limited efficiency of prolyl‐endopeptidase in the detoxification of gliadin peptides in celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2005129786–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Belghith M, Bluestone J A, Barriot S.et al TGF‐beta‐dependent mechanisms mediate restoration of self‐tolerance induced by antibodies to CD3 in overt autoimmune diabetes. Nat Med 200391202–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Keymeulen B, Vandemeulebroucke E, Ziegler A G.et al Insulin needs after CD3‐antibody therapy in new‐onset type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 20053522598–2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Harlan D M, von Herrath M. Immune intervention with anti‐CD3 in diabetes. Nat Med 200511716–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Molberg O, Uhlen A K, Jensen T.et al Mapping of gluten T‐cell epitopes in the bread wheat ancestors: implications for celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2005128393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Spaenij‐Dekking L, Kooy‐Winkelaar Y, van Veelen P.et al Natural variation in toxicity of wheat: potential for selection of nontoxic varieties for celiac disease patients. Gastroenterology 2005129797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Spaenij‐Dekking E H, Kooy‐Winkelaar E M, Nieuwenhuizen W F.et al A novel and sensitive method for the detection of T cell stimulatory epitopes of alpha/beta‐ and gamma‐gliadin. Gut 2004531267–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.WGO‐OMGE practice guideline: celiac disease 2005 www.worldgastroenterology.org/globalguidelines (accessed 10 April 2006)

- 124.NIH consensus development conference on celiac disease: final statement 2004 http://consensus.nih.gov/2004/2004CeliacDisease118html.htm (accessed 10 April 2006)

- 125.Corazza G R, Andreani M L, Biagi F.et al The smaller size of the ‘coeliac iceberg' in adults. Scand J Gastroenterol 199732917–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Riestra S, Fernandez E, Rodrigo L.et al Prevalence of Coeliac disease in the general population of northern Spain. Strategies of serologic screening. Scand J Gastroenterol 200035398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Volta U, Bellentani S, Bianchi F B.et al High prevalence of celiac disease in Italian general population. Dig Dis Sci 2001461500–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Gomez J C, Selvaggio G S, Viola M.et al Prevalence of celiac disease in Argentina: screening of an adult population in the La Plata area. Am J Gastroenterol 2001962700–2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hovell C J, Collett J A, Vautier G.et al High prevalence of coeliac disease in a population‐based study from Western Australia: a case for screening? Med J Aust 2001175247–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.