Abstract

Background and aims

Germline mutations in the LKB1 gene are known to cause Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome, which is an autosomal dominant disorder characterised by hamartomatous polyposis and mucocutaneous pigmentation. This syndrome is associated with an increased risk of malignancies in different organs but there is a lack of data on cancer range and risk in LKB1 germline mutation carriers.

Patients and methods

The cumulative incidence of cancer in 149 Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients with germline mutation(s) in LKB1 was estimated using Kaplan‐Meier time to cancer onset analyses and compared between relevant subgroups with log rank tests.

Results

Thirty two cancers were found in LKB1 mutation carriers. Overall cancer risks at ages 30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 years were 6%, 18%, 31%, 41%, and 67%, respectively. There were similar overall cancer risks between male and female carriers. However, there were overall cancer risk differences for exon 6 mutation carriers versus non‐exon 6 mutation carriers (log rank p = 0.022 overall, 0.56 in males, 0.0000084 in females). Most (22/32) of the cancers occurred in the gastrointestinal tract, and the overall gastrointestinal cancer risks at ages 40, 50, 60, and 70 years were 12%, 24%, 34%, and 63%, respectively. In females, the risks for developing gynaecologic cancer at ages 40 and 50 years were 13% and 18%, respectively.

Conclusions

Mutations in exon 6 of LKB1 are associated with a higher cancer risk than mutations within other regions of the gene. Moreover, this study provides age related cumulative risks of developing cancer in LKB1 mutation carriers that should be useful for developing a tailor made cancer surveillance protocol for Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients.

Keywords: Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome, cumulative cancer risk, LKB1 gene mutations, surveillance, exon specific risk

Pathological germline mutations in the tumour suppressor LKB1 (alias STK11) gene1,2,3 lead to Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome (OMIM#175200), a dominantly inherited disorder characterised typically by perioral pigmentation and hamartomatous polyposis.

Several studies have shown that mutation detection rates in the LKB1 gene vary between 50% and 90% depending on the availability of the Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome population studied and the methods used for detection of mutations.1,4,5 Heterogeneity seems to be a common feature among most of the studies reported to date.4,6,7 Recently, additional evidence has been found for the role of the 19q13.4 locus in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome LKB1 negative mutation carriers.8,9

Since identification of LKB1 as the gene responsible for Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome, molecular characterisation of LKB1 mutations and identification of its substrate protein have been the foci of many recent published studies. More than 150 or so mutations in the LKB1 gene described to date result in inactivation or loss of function of LKB1.4,5 This differs from mutations in other kinase (for example, KIT, BRAF, PDGFRA, and EGFR) genes that are associated with cancer due to a gain in function of kinase activity.10,11,12,13 Thus far, LKB1 is the only known kinase which, when inactivated, can lead to cancer. Ubiquitously expressed,1LKB1 was shown to play a role in the cell cycle,3 and has been connected through protein‐protein interaction to several pathways that influence cell proliferation.14,15,16,17,18

Heterozygous Lkb1 knockout mice develop hamartomatous polyps in the gastrointestinal tract without inactivation of the remaining wild‐type Lkb1 allele, suggesting that polyposis does not result from loss of heterozygosity,19 but from LKB1 haploinsufficiency.20 Subsequently, these heterozygous mice have been shown to develop hepatocellular carcinoma.21

Compelling evidence that Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients have a high risk of cancer came from retrospective cohort studies with Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome families and sporadic cases. Most of these studies compared cancer incidence in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome with that in the general population,22,23 but this comparison is inaccurate as the diagnosis of Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome was made based only on clinical criteria,23 and misdiagnosis can occur.24 The avenue of mutation search in the LKB1 gene paved the way for genetic testing as an additional criterion for diagnosing Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome, which facilitated identifying a homogeneous population of Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome families with LKB1 mutations. Cancer risks can be estimated more accurately in this population although not all Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome families have mutations in LKB1 even if they are linked to the 19p13.3 locus. Recently, one study estimated cancer risks in a large cohort of Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome families linked to the 19p13.3 locus with and without mutation in LKB1 but failed to find any genotype‐phenotype correlation.25

In the present study, we estimate cumulative cancer risks by age in a large cohort of Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients with LKB1 mutations. Moreover, we show that mutations in exon 6 of the LKB1 gene are associated with higher cancer risks than mutations within other regions of the gene. Such knowledge should be valuable for counselling and may also be useful in tailoring Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patient targeted cancer surveillance efforts.

Subjects and methods

Patients and families

From 1985 to 2004, a series of Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients were referred by gastroenterologists, gastrointestinal surgeons, and geneticists to the following laboratories for genetic analysis within Europe and Asia: (i) Department of Cell Biology, Cancer Predisposition Unit, University of Geneva, Switzerland; Sezione di Genetica Medica Dip Biomedicina dell'Età Evolutiva, Università di Bari, Italy; (ii) Cancer Research Centre and Cancer Research Institute, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Korea; (iii) Hereditary Tumor Research Project, Tokyo Metropolitan Komagome Hospital, Japan; and (iv) our own laboratory at the University of Geneva. The Geneva referred patients were from Europe (France, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey), the USA (Alabama, New York, Utah), Brazil, the Middle East (Iran, Israel), and North Africa (Algeria, Morocco).

All study patients satisfied the following established criteria for a diagnosis of Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome: presence of characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation and hamartomatous polyps with a core of large tree‐like branches of smooth muscle covered with displaced epithelium specific to the involved area of the gastrointestinal tract. Histological aspects of Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome polyps were unambiguous in all cases.

Clinical data were collected using a standardised questionnaire and patients' medical records. Characteristic features defining the clinical diagnosis were: age at first symptoms, initial symptoms and histology of the polyp biopsy, presence of mucocutaneous pigmentation, localisation of the polyps, presence of cancer, histology type, organ involved, and age at cancer diagnosis. When at least two or more individuals were affected in the same family, they were considered as familial cases, and otherwise as likely to have been isolated. Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients were considered as apparently isolated cases based on the presence of hamartomatous polyposis and mucocutaneous pigmentation without any family history. Finally, a Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patient was defined as a definite isolated case caused by a de novo mutation only if the mutation was not present in the parents after exclusion of non‐paternity or non‐maternity.

None of the patients were selected preferentially for inclusion in the study because of a past history of cancer. Cancers that were eligible for inclusion in the analysis were all primary tumours (excluding non‐melanotic skin cancer).

The study was performed with ethics committee approval from the relevant authority in each country. Informed consent and blood samples were obtained from patients and their relatives. DNA was extracted from 10 ml of peripheral blood using the Puregene DNA Purification Kit (Gentra Systems, Inc, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

LKB1 mutation search

A combination of single strand conformational polymorphism analysis and direct sequencing was used to screen the nine LKB1 exons and flanking intronic sequences in germline genomic DNA extracted from blood leucocytes or normal tissue samples. Polymerase chain reaction and gel conditions have been reported previously.4 Mutations in the LKB1 gene identified in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients were coded according to the published gene sequence (GenBank accession Nos: exon 1, AF032984; exons 2–8, AF032985; exon 9, AF032986) following standard nomenclature.26 STK11 protein sequences of Homo sapiens (GenBank accession No NP 000446), Mus musculus (NP 035622), and xenopusXEEK1 (Q91604) were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information protein database accessed at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/. Alignments were made using the Clustal W (version 1.8) multiple sequence alignment program at Baylor College of Medicine Search Launcher accessed at http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu/SearchLauncher/.

Paternity and maternity testing

Paternity and maternity testing were performed for all families in which LKB1 mutations were found, and in all isolated patients for whom parental DNA samples were available. This was done by analysis of at least three highly informative microsatellite markers (D19S886, D19S878, D19S565), but in cases where these markers were not informative or there was any suspicion of non‐paternity or non‐maternity, further markers in other chromosomes were analysed. Radioactively labelled primers were used, and genotypes were determined by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography.8

Statistical analysis

Cancer incidence in patients was truncated at age 75 years. A classification scheme for grouping cancers by diagnosis was devised primarily based on topography to subdivide carcinomas by primary site. Cancers were coded using the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases. Overall and subgroup cancer risks (with 95% confidence limits) were estimated using Kaplan‐Meier (product‐limit) time to cancer onset analyses. Differences in cancer risks between various relevant subgroups (see Results) were assessed with log rank tests. The time intervals in these analyses were the time between birth and first cancer diagnosis for Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients with cancer, and the time between birth and last contact or death for Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients without cancer. Associations between categorical variables were assessed with Fisher's exact tests. Randomness of the distribution of mutations across LKB1 gene exons was assessed with a χ2 goodness of fit test. In all analyses, a p value <0.05 (0.10) was considered statistically (or borderline) significant.

Results

Characteristics of patients with Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome

Data on 149 Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients comprising 76 males and 73 females in whom an LKB1 mutation had been identified were available for this study. None of the families linked to 19p13.3 without mutation in LKB1 were included. There were 133 familial cases derived from 25 families (mean family size including proband = 5), 15 isolated cases, and one case with status missing (diagnosed Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome but familial/isolated status unknown).

LKB1 mutations

Forty of the mutations identified in the LKB1 gene were unique. Fifteen mutations were truncating, leading to the creation of premature stop codons and resulting in disruption of kinase activity, eight were within splice sites, nine were deletions, and eight were missense mutations. When the amino acid sequences of human, mouse, and xenopus homologues of the STK11 were compared by alignment using the Clustal W program, all missense mutations occurred within a highly conserved amino acid and they were located in the kinase domain (49‐309aa) encoded by exons 1–8 (see supplementary figure; the supplementary figure can be viewed on the Gut website at http://www.gutjnl.com/supplemental). Most of these missense mutations were inactivating mutations as they were assayed for autophosphorylation and showed that they abolish or dramatically reduce the kinase activity of the mutant protein.4,27 The splice site mutations observed in affected patients were not observed in 100 non‐Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome individuals who were tested as population controls. Mutations were spread throughout the gene but no mutation in exon 9 was identified in any of the Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients. The distribution of mutations within exons 1–8 was not random (p<0.001); truncating mutations were overrepresented in exons 4 and 6, and missense mutations were overrepresented in exons 4 and 8.

Cumulative cancer risks

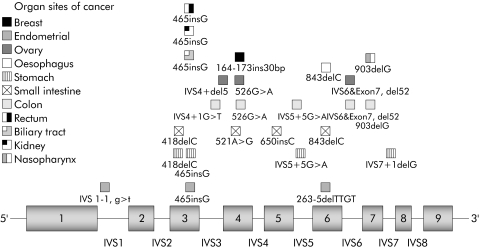

Thirty two cancers were found in 29 mutation carriers. One patient was diagnosed with malignancies at two different sites and another had cancers at three different sites. Details of the frequency and different sites of cancer are summarised in fig 1. Tumours of the gastrointestinal tract and gynaecological cancers were the most commonly reported malignancy sites.

Figure 1 Cancer sites associated with LKB1 gene mutations in patients with Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome. Each organ affected by cancer is represented by a different symbol placed in front of the site of the exon or exon‐intron junction of the LKB1 gene where the germline mutation was found.

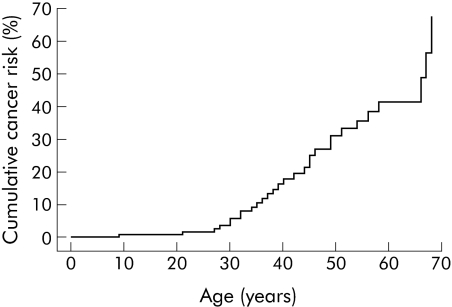

The carcinomas were subdivided by primary site, and cumulative cancer risks by site, age, and sex were estimated (table 1). Among 149 LKB1 mutation carriers, overall risks for developing a first cancer at 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 years were 1%, 6%, 18%, 31%, 41%, and 67%, respectively (see table 1 for 95% confidence limits and also fig 2). The general population risk for cancer by age 60 years is 8.5%, hence the risk for cancer in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients is increased 4–5‐fold. Overall cancer risks were similar in males and females (log rank p including/excluding breast and gynaecological cancers = 0.23/0.95).

Table 1 Cumulative cancer risk by site, age, and sex in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome LKB1 gene mutation carriers.

| Type of cancer (n out of total or by sex) | Cancer risk by age (y) (95% CL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | |

| All cancers (32 in 149 total) | 1% (0–2) | 6% (1–10) | 18% (9–26) | 31% (18–41) | 41% (26–53) | 67% (31–84) |

| All cancers (13 in 76 males) | 1% (0–4) | 5% (0–11) | 10% (1–18) | 24% (8–38) | 39% (16–56) | 55% (13–76) |

| All cancers (19 in 73 females) | – | 6% (0–13) | 27% (11–40) | 39% (19–54) | 45% (22–61) | 59% (20–79) |

| Gastrointestinal (22 in 149 total) | 1% (0–2) | 4% (0–8) | 12% (5–19) | 24% (12–35) | 34% (18–46) | 63% (23–82) |

| Gastrointestinal (12 in 76 males) | 1% (0–4) | 5% (0–11) | 10% (1–18) | 24% (8–38) | 36% (13–53) | 52% (9–75) |

| Gastrointestinal (10 in 73 females) | – | 2% (0–7) | 14% (2–26) | 24% (6–39) | 31% (9–48) | 48% (3–73) |

| Gynaecological (7 in 73 females) | – | 4% (0–9) | 13% (1–24) | 18% (3–32) | – | – |

| Breast (1 in 73 females) | – | – | 5% (0–13) | – | – | – |

| Other (2 in 149 total) | – | – | – | – | 3% (0–9) | 27% (0–59) |

| Other (1 in 76 men) | – | – | – | – | 6% (0–16) | – |

| Other (1 in 73 women) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

95% CL, 95% confidence limits.

–, not estimable.

Figure 2 Risk of all cancers in patients with Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome with LKB1 gene mutations. Ages displayed are the time between birth and first cancer diagnosis for those with cancer, and the time between birth and either last contact or death for those without cancer.

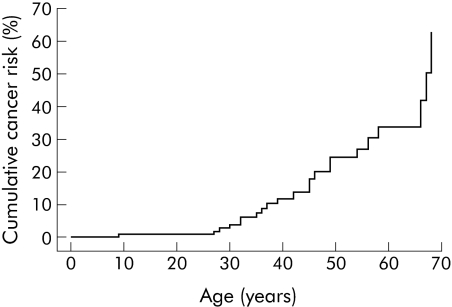

The overall risks for gastrointestinal (oesophageal, stomach, small intestine, biliary tract, colon, and rectum) cancer at ages 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 years were 1%, 4%, 12%, 24%, 34%, and 63%, respectively (see table 1 for 95% confidence limits and also fig 3). Almost all of the latter were much greater than the general population gastrointestinal cancer risk at age 60 years of just 1.3%. Gastrointestinal cancer risks were similar in men and women (log rank p = 0.9).

Figure 3 Risk of gastrointestinal cancer (oesophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, and biliary tract) in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients with LKB1 gene mutations. Ages shown are the time between birth and first gastrointestinal cancer diagnosis for those with gastrointestinal cancer, and the time between birth and either last contact or death for those without gastrointestinal cancer (including patients with other cancers).

Of the 22 gastrointestinal tract cancers, the colon and rectum were the organs most commonly affected (n = 11), followed by stomach (n = 5), small intestinal (n = 4), oesophageal (n = 1), and biliary tract (n = 1) cancers. Slightly more men than women had colorectal cancer (6 v 5) but the risk difference was not statistically significant. Similarly, five patients (three men and two women) were diagnosed with stomach adenocarcinomas between the ages of 32 and 58 years (also a non‐significant risk difference by sex).

Among 73 female Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients, seven developed gynaecologic cancer (four uterine and three ovarian). Age at diagnosis of uterine cancer ranged from 35 to 45 years while that for ovarian cancer ranged from 22 to 38 years. The risks for developing gynaecologic cancer at ages 30, 40, and 50 years were 4%, 13%, and 18%, respectively (see table 1 for 95% confidence limits). Among LKB1 gene mutation carriers, one woman developed breast cancer and another developed nasopharynx cancer.

Cancer risk differences between familial and isolated Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome cases

There were no statistically significant cancer risk differences between the 133 familial and 15 isolated Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome cases (table 2) (p values (overall, males, females) or for females only: all cancer p = (0.29, 0.45, 0.39); gastrointestinal cancer p = (0.11, 0.37, 0.092); gynaecological cancer p = 0.60; breast cancer p not estimable; other cancer p = (0.86, 0.81, not estimable)). Only overall (perhaps) and female gastrointestinal cancer risk difference p values (0.11 and 0.092, respectively) were of borderline significance.

Table 2 Cancer risk differences in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients between familial (F) versus isolated (S) cases.

| Sex | No of cancers of each type (% of subgroup) by PJS case type (F or S) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cancers | Gastrointestinal | Gynaecological | Breast | Other | ||||||

| F | S | F | S | F | S | F | S | F | S | |

| Overall | 27 (21%) | 2 (13%) | 20 (15%) | 2 (13%) | – | – | – | – | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| p = 0.29* | p = 0.11 | – | – | p = 0.86 | ||||||

| Males | 12 (18%) | 1 (17%) | 11 (16%) | 1 (17%) | – | – | – | – | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| p = 0.45 | p = 0.37 | – | – | p = 0.81 | ||||||

| Females | 15 (24%) | 1 (11%) | 9 (14%) | 1 (11%) | 7 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| p = 0.39 | p = 0.092 | p = 0.60 | NE | NE | ||||||

*Log rank test, two tailed p value.

PJS, Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome. NE, not estimable.

Genotype‐phenotype correlations in LKB1 mutation carriers

Cancer risk differences between the 29 missense and 100 truncating mutation carriers were also estimated. Twenty carriers with cancer had truncating mutations and four were associated with missense mutations. There were similar cumulative overall and specific cancer risks between the two mutation types (table 3) (p values (overall, males, females) or for females only: all cancer p = (0.45, 0.66, 0.57); gastrointestinal cancer p = (0.40, 0.50, 0.61); gynaecological cancer p = 0.74; breast cancer p = 0.72; other cancer p = (0.73, 0.62, not estimable)).

Table 3 Cancer risk differences in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients between missense (M) versus truncating (T) mutation carriers.

| Sex | No of cancers of each type (% of subgroup) by mutation type (M or T) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cancers | Gastrointestinal | Gynaecological | Breast | Other | |||||||

| M | T | M | T | M | T | M | T | M | T | ||

| Overall | 20 (21%) | 4 (14%) | 15 (15%) | 3 (10%) | – | – | – | – | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| p = 0.45 | p = 0.40 | – | – | p = 0.73 | |||||||

| Males | 9 (18%) | 2 (14%) | 8 (16%) | 2 (14%) | – | – | – | – | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| p = 0.66 | p = 0.50 | – | – | p = 0.62 | |||||||

| Females | 11 (24%) | 2 (13%) | 7 (15%) | 1 (7%) | 5 (11%) | 1 (7%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| p = 0.57 | p = 0.61 | p = 0.74 | p = 0.72 | NE | |||||||

NE, not estimable.

Most of the cancers observed in the study were associated with mutations located within the kinase domain spanning exon 2 to exon 7 that corresponds to amino acids 49–309 in the amino acid sequence of the STK11 protein. There were no cancers observed in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients with mutations on exon 1 or exon 8. For exons 2 to 5 and 7, there were very similar cumulative overall and specific cancer risks (table 4). However, there were some significant (or borderline) cumulative overall and specific cancer risk differences for exon 6 (p values (overall, males, females) or for females only: all cancer p = (0.022, 0.56, 0.0000084); gastrointestinal cancer p = (0.079, 0.49, 0.00030); gynaecological cancer p = 0.0055). Overall, three of seven (43%) Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients with a mutation on exon 6 had developed cancer, compared to 26 of 142 (18%) Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients without an exon 6 mutation.

Table 4 Cancer risk differences in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients between LBK1 exon 3 or exon 6 mutation (+ or −) subgroups.

| Exon | Sex | No of cancers of each type (% of subgroup) by LKB1 exon 3 or exon 6 mutation status (+ or −) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cancers | Gastrointestinal | Gynaecological | Breast | Other | |||||||

| + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | ||

| 3 | Overall | 6 (30%) | 23 (18%) | 6 (30%) | 16 (12%) | – | – | – | – | 1 (5%) | 1 (1%) |

| p = 0.74 | p = 0.30 | – | – | p = 0.22 | |||||||

| Males | 3 (30%) | 10 (15%) | 3 (10%) | 9 (14%) | – | – | – | – | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | |

| p = 0.26 | p = 0.21 | – | – | p = 0.74 | |||||||

| Females | 3 (30%) | 13 (21%) | 3 (10%) | 7 (11%) | 2 (10%) | 5 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | |

| p = 0.53 | p = 0.91 | p = 0.81 | p = 0.59 | p = 0.32 | |||||||

| 6 | Overall | 3 (43%) | 26 (18%) | 2 (29%) | 20 (14%) | – | – | – | – | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) |

| p = 0.022 | p = 0.079 | – | – | p = 0.86 | |||||||

| Males | 1 (33%) | 12 (16%) | 1 (33%) | 11 (15%) | – | – | – | – | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| p = 0.56 | p = 0.49 | – | – | p = 0.82 | |||||||

| Females | 2 (50%) | 14 (20%) | 1 (25%) | 9 (13%) | 1 (25%) | 6 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| p = 0.0000084 | p = 0.00030 | p = 0.0055 | NE | NE | |||||||

NE, not estimable.

Discussion

A total of 149 Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients with LKB1 germline mutations were studied to determine the age related cumulative risks of developing cancer. The results confirmed that carriers of a germline mutation in LKB1 have a high lifetime risk of developing cancer.

The results of the study could have been biased in several ways. Firstly, cancer outcomes might have been influenced by the fact that only patients who survived (from intestinal intussusceptions) were available for mutation screening, which could have led to an overrepresentation of tumour types with a favourable prognosis and underrepresentation of tumours with a less favourable prognosis.21 Secondly, estimates based on families ascertained for linkage studies may overestimate cancer risk in mutation carriers while population based series may underestimate the risk.28 Hence these factors cannot be excluded. On the other hand, the majority of families included were originally selected for a linkage study,8 not because of a diagnosis of cancer. In addition, because the cancers observed in our Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients were not clustered in just a few families, bias may have been correspondingly limited.

The estimated risks for all cancers at ages 20, 30, 40, and 50 years and for gastrointestinal cancer were similar to those reported in another recent study.25 However, that study may have overestimated breast cancer risks. The discrepancy with the present results may be due to the inclusion of Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome cases from families linked to the 19p13.3 locus without an LKB1 mutation.25 Interestingly, LKB1 somatic mutations are rare in breast cancer,29 which is consistent with the low breast cancer risk found in the present study but contrasts with the high breast cancer risk in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients reported previously.25 Moreover, lung cancers were included without information on additional relevant risk factors such as smoking behaviour and histology type.25 Pancreatic, multiple myeloma, liver, and testis cancer were not observed in the present study. Absence of pancreatic cancer in the present study has also been observed elsewhere,23,30 and may have been due to the specific collection of Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients studied or to the absence of other factors (for example, environmental, gene modifiers) that were present in another study.25 On the other hand, single cases of nasopharynx, oesophagus, and kidney carcinomas and biliary adenocarcinoma were found in the present collection of Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients.

Remarkably, most of the observed cancers were associated with mutations located within the kinase domain (fig 1). This is consistent with several studies and case reports on LKB1 mutations associated with cancer in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome.7 Based on this observation, analyses were performed that showed there was statistically significant evidence for a correlation between mutations in exon 6 and higher cancer risk. The risk difference was observed in females for both gastrointestinal and gynaecological cancers (table 4). Interestingly, many cases of cancer associated with mutations in exon 6 of the LKB1 gene in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients have been reported (table 5). Nevertheless, that this finding was not reported by Lim and colleagues25 might have been due to the particular Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patient sample studied or to inclusion of families linked to 19p without mutations in the LKB1 gene, thus reducing the chances of finding a correlation. An additional explanation could be that duration of follow up was not sufficient for the detection of cancer in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome exon 6 mutation carriers. The reason why only exon 6 mutations were associated with higher cancer risks in the present study despite the fact that other exons, such as 2–5, 7, and 8 are also located in the kinase domain, remains elusive. Recently, many proteins (for example, P53, Cdc37 and Hsp90, STRADα, PTEN)14,18,31,32 responsible for cancer syndrome when mutated or involved in cancer pathways were reported to interact with the kinase domain of LKB1, but the protein interacting domains were not mapped. Accordingly, one of these protein interacting domains might be localised in exon 6 and therefore could explain the high cancer risk of mutation in this exon. Further studies are required to confirm these associations and understand the molecular basis for this genotype‐phenotype relationship.

Table 5 Spectrum of cancer associated with exon 6 mutations of the LKB1 gene in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients reported in other studies.

| References | Type of mutation | Mutation | No and type of cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ylikorkala, 19995 | Deletion: 773‐780del7bp | 263Fs† | 1 pancreas |

| Deletion: 747‐760del13bp | 257Fs | 1 colon | |

| Deletion: 604‐623del19bp | 248Fs | 1 ovary | |

| 1 testis | |||

| Boardman, 20006 | Insertion: 844insC | 281Fs | 1 pancreas |

| 1 prostate | |||

| 1 colon | |||

| Olschwang, 200135 | Deletion: 843delC | 281Fs | 1 pancreas |

| 1 kidney | |||

| Nakamura, 200236 | Deletion: 843delC | 281Fs | 1 duodenum |

| Lim, 20037 | Deletion: 846del | 282Fs | 2 breast |

| Takahashi, 200437 | Insertion: 757‐758insT | 252Fs | 1 Stomach |

| Amos, 200438 | Insertion: 842‐843insC | 280Fs | 2 carcinomas* |

| Present study | Deletion: 843delC | 281Fs | 1 oesophagus |

| 1 small intestine | |||

| Deletion: 263‐5delTTGT | 263Fs | 1 endometrial |

FS, frameshift.

*Organ not determined.

Based on the results of studies that showed an increased relative cancer risk in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients, some investigators have suggested surveillance of Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients.33,34 Most of these proposals favour the use of endoscopy (gastroscopy, colonoscopy, camera capsule), radiography (mammography, abdominal and endoscopic ultrasounds, computed tomography scan), and biological tests. However, there are no clear guidelines established for surveillance, which has been shown to be efficient for the detection of cancer, for Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients. Many investigators disagree about the time for initiation of the screening tests and the intervals between them. Although the spectrum of all possible cancers associated with Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome is not represented in our study, particularly the minor cancer type, the results of the present analysis should be useful for developing a tailor made cancer surveillance protocol for Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients.

Specifically, the present results indicate that the risks for cancer, and especially gastrointestinal cancer, associated with germline LKB1 mutations are sufficiently high to warrant screening for cancer of the stomach, small intestine, and colorectal organs in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients. Furthermore, the present risk findings indicate that cancer surveillance is justified before age 20 years for gastrointestinal cancer, beginning at age 20 years for gynaecological cancer, and before age 30 years for breast cancer. These suggestions contrast with those of a previous report that recommends beginning surveillance for gastrointestinal cancer after 20 years of age.25 Further prospective studies assessing the efficiency of screening protocols based on such suggestions are needed to clarify this issue in the case of gastrointestinal cancer. However, the comparative risk analyses in the present study indicate that routine surveillance of Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients is probably not justified for other cancers, except perhaps for those Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome patients with a mutation on LKB1 exon 6.

The supplementary figure can be viewed on the Gut website at http://www.gutjnl.com/supplemental.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The participation of all Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome family members and patients and the collaboration of the physicians, gastroenterologists, surgeons, and geneticists who endorsed this project are gratefully acknowledged. This study was supported by the Ligue Genevoise contre le Cancer.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

The supplementary figure can be viewed on the Gut website at http://www.gutjnl.com/supplemental.

References

- 1.Jenne D E, Reimann H, Nezu J.et al Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome is caused by mutations in a novel serine threonine kinase. Nat Genet 19981838–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemminki A, Markie D, Tomlinson I.et al A serine/threonine kinase gene defective in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome. Nature 1998391184–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tiainen M, Ylikorkala A, Makela T P. Growth suppression by Lkb1 is mediated by a G(1) cell cycle arrest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999969248–9251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehenni H, Gehrig C, Nezu J.et al Loss of LKB1 kinase activity in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome, and evidence for allelic and locus heterogeneity. Am J Hum Genet 1998631641–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ylikorkala A, Avizienyte E, Tomlinson I P.et al Mutations and impaired function of LKB1 in familial and non‐familial Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome and a sporadic testicular cancer. Hum Mol Genet 1999845–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boardman L A, Couch F J, Burgart L J.et al Genetic heterogeneity in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome. Hum Mutat 20001623–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim W, Hearle N, Shah B.et al Further observations on LKB1/STK11 status and cancer risk in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome. Br J Cancer 200389308–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehenni H, Blouin J L, Radhakrishna U.et al Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome: confirmation of linkage to chromosome 19p13.3 and identification of a potential second locus, on 19q13.4. Am J Hum Genet 1997611327–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hearle N, Lucassen A, Wang R.et al Mapping of a translocation breakpoint in a Peutz‐Jeghers hamartoma to the putative PJS locus at 19q13.4 and mutation analysis of candidate genes in polyp and STK11‐negative PJS cases. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 200441163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies H, Bignell G R, Cox C.et al Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002417949–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinrich M C, Corless C L, Duensing A.et al PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 2003299708–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirota S, Ohashi A, Nishida T.et al Gain‐of‐function mutations of platelet‐derived growth factor receptor alpha gene in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastroenterology 2003125660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paez J G, Janne P A, Lee J C.et al EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science 20043041497–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karuman P, Gozani O, Odze R D.et al The Peutz‐Jegher gene product LKB1 is a mediator of p53‐dependent cell death. Mol Cell 200171307–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marignani P A, Kanai F, Carpenter C L. LKB1 associates with Brg1 and is necessary for Brg1‐induced growth arrest. J Biol Chem 200127632415–32418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith D P, Rayter S I, Niederlander C.et al LIP1, a cytoplasmic protein functionally linked to the Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome kinase LKB1. Hum Mol Genet 2001102869–2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baas A F, Boudeau J, Sapkota G P.et al Activation of the tumour suppressor kinase LKB1 by the STE20‐like pseudokinase STRAD. Embo J 2003223062–3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehenni H, Lin‐Marq N, Buchet‐Poyau K.et al LKB1 interacts with and phosphorylates PTEN: a functional link between two proteins involved in cancer predisposing syndromes. Hum Mol Genet 2005142209–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemminki A, Tomlinson I, Markie D.et al Localization of a susceptibility locus for Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome to 19p using comparative genomic hybridization and targeted linkage analysis. Nat Genet 19971587–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyoshi H, Nakau M, Ishikawa T O.et al Gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis in Lkb1 heterozygous knockout mice. Cancer Res 2002622261–2266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakau M, Miyoshi H, Seldin M F.et al Hepatocellular carcinoma caused by loss of heterozygosity in Lkb1 gene knockout mice. Cancer Res 2002624549–4553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giardiello F M, Welsh S B, Hamilton S R.et al Increased risk of cancer in the Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome. N Engl J Med 19873161511–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boardman L A, Thibodeau S N, Schaid D J.et al Increased risk for cancer in patients with the Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1998128896–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boardman L A, Pittelkow M R, Couch F J.et al Association of Peutz‐Jeghers‐like mucocutaneous pigmentation with breast and gynecologic carcinomas in women. Medicine (Baltimore) 200079293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim W, Olschwang S, Keller J J.et al Relative frequency and morphology of cancers in STK11 mutation carriers. Gastroenterology 20041261788–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antonarakis S E. Recommendations for a nomenclature system for human gene mutations. Nomenclature Working Group. Hum Mutat 1998111–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Resta N, Stella A, Susca F C.et al Two novel mutations and a new STK11/LKB1 gene isoform in Peutz‐Jeghers patients. Hum Mutat 20022078–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ford D, Easton D F, Stratton M.et al Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet 199862676–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bignell G R, Barfoot R, Seal S.et al Low frequency of somatic mutations in the LKB1/Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome gene in sporadic breast cancer. Cancer Res 1998581384–1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spigelman A D, Murday V, Phillips R K. Cancer and the Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome. Gut 1989301588–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boudeau J, Deak M, Lawlor M A.et al Heat‐shock protein 90 and Cdc37 interact with LKB1 and regulate its stability. Biochem J 2003370849–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baas A F, Kuipers J, van der Wel N N.et al Complete polarization of single intestinal epithelial cells upon activation of LKB1 by STRAD. Cell 2004116457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomlinson I P, Houlston R S. Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet 1997341007–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulmann K, Hollerbach S, Kraus K.et al Feasibility and diagnostic utility of video capsule endoscopy for the detection of small bowel polyps in patients with hereditary polyposis syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol 200510027–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olschwang S, Boisson C, Thomas G. Peutz‐Jeghers families unlinked to STK11/LKB1 gene mutations are highly predisposed to primitive biliary adenocarcinoma. J Med Genet 200138356–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakamura T, Suzuki S, Yokoi Y.et al Duodenal cancer in a patient with Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome: molecular analysis. J Gastroenterol 200237376–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi M, Sakayori M, Takahashi S.et al A novel germline mutation of the LKB1 gene in a patient with Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome with early‐onset gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol 2004391210–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amos C I, Keitheri‐Cheteri M B, Sabripour M.et al Genotype‐phenotype correlations in Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet 200441327–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.