Abstract

Background and aims

Activated pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) are implicated in the production of alcohol induced pancreatic fibrosis. PSC activation is invariably associated with loss of cytoplasmic vitamin A (retinol) stores. Furthermore, retinol and ethanol are known to be metabolised by similar pathways. Our group and others have demonstrated that ethanol induced PSC activation is mediated by the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway but the specific role of retinol and its metabolites all‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and 9‐cis retinoic acid (9‐RA) in PSC quiescence/activation, or its influence on ethanol induced PSC activation is not known. Therefore, the aims of this study were to (i) examine the effects of retinol, ATRA, and 9‐RA on PSC activation; (ii) determine whether retinol, ATRA, and 9‐RA influence MAPK signalling in PSCs; and (iii) assess the effect of retinol supplementation on PSCs activated by ethanol.

Methods

Cultured rat PSCs were incubated with retinol, ATRA, or 9‐RA for varying time periods and assessed for: (i) proliferation; (ii) expression of α smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA), collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin; and (iii) activation of MAPKs (extracellular regulated kinases 1 and 2, p38 kinase, and c‐Jun N terminal kinase). The effect of retinol on PSCs treated with ethanol was also examined by incubating cells with ethanol in the presence or absence of retinol for five days, followed by assessment of α‐SMA, collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin expression.

Results

Retinol, ATRA, and 9‐RA significantly inhibited: (i) cell proliferation, (ii) expression of α‐SMA, collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin, and (iii) activation of all three classes of MAPKs. Furthermore, retinol prevented ethanol induced PSC activation, as indicated by inhibition of the ethanol induced increase in α‐SMA, collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin expression.

Conclusions

Retinol and its metabolites ATRA and 9‐RA induce quiescence in culture activated PSCs associated with a significant decrease in the activation of all three classes of MAPKs in PSCs. Ethanol induced PSC activation is prevented by retinol supplementation.

Keywords: pancreatic stellate cells, vitamin A, mitogen activated protein kinases, pancreatic fibrosis

Pancreatic fibrosis is a common histopathological feature of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis.1 Fibrogenesis involves a specific cell type in the pancreas, namely the pancreatic stellate cell (PSC).2,3 Recent studies have demonstrated that PSCs become activated (as indicated by proliferation, increased expression of the cytoskeletal protein α smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA), and synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins) when cultured on plastic or when exposed to ethanol and its oxidative metabolite acetaldehyde or to factors known to be upregulated during pancreatic injury such as proinflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and oxidant stress.2,3,4

PSCs in their quiescent (non‐activated) state store retinol as lipid droplets in their cytoplasm. Activation of PSCs is invariably associated with loss of the retinol containing droplets from their cytoplasm.5,6 Studies in other cell systems have established that retinol is a compound essential to normal cell biology.7 In particular, metabolites of retinol, all‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and 9‐cis retinoic acid (9‐RA), have been shown to mediate a number of cellular functions, including proliferation, differentiation, and protein synthesis.8 Metabolism of retinol has been best studied in the liver. It has been demonstrated in hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) that retinol enters the cell bound to cellular retinol binding protein.9 It is then either esterified to retinyl ester for storage or converted to retinaldehyde by retinol dehydrogenase (RolDH) and subsequently to retinoic acid by retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RALDH).10 Two forms of retinoic acid, ATRA and 9‐RA, serve as ligands for two families of nuclear receptors: retinoic acid receptors (RARα, β, and γ) and retinoid X receptors (RXRα, β, and γ).8 RARs bind to ATRA with high affinity whereas 9‐RA is a bifunctional ligand which can bind to and activate both RARs and RXRs.11 Following ligand binding, these compounds interact with cis acting DNA sequences called retinoic acid responsive elements in the promoter regions of target genes, thereby regulating gene expression.8 It is of interest that studies with HSCs have demonstrated that on exposure to activating factors, levels of retinoic acid and expression of their receptors is decreased.12 Moreover, maintenance of the quiescent phenotype of HSCs has been shown to be dependent on adequate levels of retinoic acid and its receptors in the cells.12 A recent study by Jaster and colleagues13 has reported decreased proliferation and collagen synthesis in PSCs on exposure to ATRA. However, there has been no comprehensive study in the literature to date examining the effects of retinol and both of its metabolites (ATRA and 9‐RA) on PSC function.

A number of observations suggest a link between metabolism of ethanol and retinol. Ethanol and its oxidative metabolite acetaldehyde are key activating factors of PSCs.3 Oxidation of ethanol to acetaldehyde is mediated by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH).10 Acetaldehyde is then further oxidised to acetic acid via aldehyde dehydrogenase.10 It has been established that the retinol metabolising enzymes RolDH and RALDH belong to the same family of alcohol and acetaldehyde metabolising dehydrogenases, respectively.10 Interestingly, studies have shown that rats chronically exposed to ethanol display significantly reduced retinoic acid levels in the liver.14 This is thought to be due to competitive inhibition by ethanol of retinol metabolism by RolDH and ADH as these enzymes can utilise both ethanol and retinol as substrates.15,16 Thus retinoic acid depletion may be an important mechanism by which ethanol promotes stellate cell activation.

In recent studies, we and others have identified the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway as a major cell signalling pathway mediating ethanol induced and growth factor induced PSC activation.17,18,19 MAPKs (which include extracellular regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), N terminal c‐Jun kinase (JNK), and p38 kinase) play a major role in regulating protein synthesis in mammalian cells.20,21 MAPKs modulate the activity of a number of downstream transcription factors and protein kinases by phosphorylation, thereby controlling gene expression and cell behaviour.21 Activation of MAPKs is a reversible process; they are inactivated by a group of protein phosphatases known as MAP kinase phosphatases (MKPs).22 These are dual specificity phosphatases which have been shown to exert their effect by dephosphorylating tyrosine and threonine residues on MAPKs, thereby leading to their inactivation.22 MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP‐1), a member of the MKP family, has recently been demonstrated to inactivate all three classes of MAPKs.23,24 It is interesting to note that recent studies have shown that MKP‐1 expression is increased on exposure to retinoic acid thereby resulting in a decrease in MAPK activity.25 However, whether retinol influences the MAPK signalling pathway or MKP‐1 expression in stellate cells (whether from the pancreas or liver) is not known.

Therefore, the aims of this study were to: (i) examine the effect of retinol and its metabolites ATRA and 9‐RA on PSC activation, (ii) determine whether retinol influences MAPK signalling and MKP‐1 expression in PSCs, and (iii) assess the influence of retinol on ethanol treated PSCs.

Methods

Cell culture reagents, protease type XIV, all‐trans retinol, ATRA, and 9‐RA were purchased from the Sigma Chemical Company (St Louis, Missouri, USA). Primers for RolDH II, RARα, RXRα, and RXRβ were obtained from Sigma Genosys Australia Pty Ltd. Sources of antibodies were as follows: α‐SMA, fibronectin, and laminin—Sigma; phospho‐ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2, total p38 kinase and total JNK—Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, Massachusetts, USA); phospho‐p38 kinase and phospho‐JNK—Promega (Sydney, Australia); MKP‐1, RARα, RXRα, and RXRβ—Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, California, USA); collagen type I—Rockland Immunochemicals (Gilbertsville, Pennsylvania, USA); and secondary goat antirabbit antibody—Dako (Sydney, Australia).

Isolation and culture of PSCs

Rat PSCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation, as detailed previously.5 (This technique results in a pure preparation of PSCs, as evidenced by positive staining for stellate cell selective markers and negative staining for possible contaminants such as endothelial cells and macrophages. The yield of PSCs is 1.5–2 million cells per rat pancreas.) Cells were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a humidified 95% air/5% CO2 atmosphere. All experiments were performed with culture activated cells (passages 1–3) with the exception of experiments to assess the effect of retinol on freshly isolated (quiescent) cells.

Expression of retinol dehydrogenase and RAR and RXR receptor mRNA using RT‐PCR

Expression of mRNA for RolDH II and the retinoic acid receptors RARα, RXRα, and RXRβ was examined using reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR). Primer sequences were as follows:

-

Rat RolDH II

-

-

Forward primer: 5′ ACC TGG CAT CTT ATC TGA AA 3′

-

-

Reverse primer: 5′ AGT CGA GTC AGC CTT GAG TA 3′26

-

-

-

Rat RARα

-

-

Forward primer: 5′ CCC AGC CAC CAT TGA GAC 3′

-

-

Reverse primer: 5′ TAC ACC ATG TTC TTC TGG ATG C 3′27

-

-

-

Rat RXRα

-

-

Forward primer: 5′ ATG AAG CGG GAA AGC TGT G 3′

-

-

Reverse primer: 5′ CAT GTT TGC CTC CAC GTA TG 3′27

-

-

-

Rat RXRβ

-

-

Forward primer: 5′ TCA ACT CCA CAG TGT CGC TC 3′

-

-

Reverse primer: 5′ TAA ACC CCA TAG TGC TTG CC 3′27

-

-

Treatment with test factors

Treatment of PSCs with retinol and retinoic acid

Culture activated PSCs (passages 1–3) were exposed to retinol (10 μM), ATRA (10 μM), or 9‐RA (10 μM) for varying periods of time. Medium was changed every 48 hours. All manipulations were performed in subdued light. Cells incubated with culture medium with an equivalent amount of vehicle—DMSO 0.1% (for ATRA and 9‐RA experiments) or DMSO 0.025% + 8 mM ethanol (for retinol experiments)—served as controls. Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion studies.

Treatment of PSCs with ethanol and retinol

To determine the effect of retinol on PSCs treated with ethanol, cells were incubated with 10 μM retinol in the presence or absence of 50 mM ethanol for five days. Medium was changed every 24 hours. At the end of the incubation period, cell lysates were collected and expression of α‐SMA, collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin was assessed by western blotting. Cell viability was assessed as described previously.

Assessment of PSC function

Cell proliferation

PSC proliferation was assessed by measuring incorporation of [3H] thymidine into cellular DNA, as previously described.28 In addition, cell counts were performed using a haemocytometer. Results are expressed as a percentage of control.

α‐Smooth muscle actin and extracellular matrix protein expression

Levels of α‐SMA, collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin in PSCs were determined by western blotting of cell lysates, as detailed previously, using a monoclonal mouse anti‐α‐SMA (1:200)3 or polyclonal rabbit anticollagen I (1:1000), antifibronectin (1:1000), and antilaminin (1:1000) antibodies.29,30 A goat antimouse antibody (1:2000) or a goat antirabbit antibody (1:2000) was used as the secondary antibody. Expression of α‐SMA, collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin was detected by the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) technique using the Amersham's enhanced ECL kit, and quantified using densitometry (BioRad GelDoc Image One software).

Detection of MAPK activation

ERK1/2, p38 kinase, and JNK activation in culture activated PSCs exposed to retinol (10 μM), ATRA (10 μM), or 9‐RA (10 μM) for 4, 24, and 48 hours was assessed by western blotting of cell lysate proteins, as described previously.17,28 To confirm that total MAPK levels were unchanged by the treatments, aliquots of the above cell lysates were subjected to western blotting analysis using rabbit polyclonal antibodies against ERK1/2, p38 kinase, or JNK (1:1000), which recognise both the phosphorylated and non‐phosphorylated forms of the enzymes; the blots were then analysed by densitometry.

Assessment of RAR and RXR protein expression in PSCs

RAR and RXR expression in PSCs treated with 10 µM ATRA or 10 µM 9‐RA for 4, 24, and 48 hours was assessed by western blotting using polyclonal rabbit antibodies against RARα, RXRα, or RXRβ (1:200).

Detection of MKP‐1 expression

MKP‐1 expression in PSCs incubated with retinol, ATRA, or 9‐RA for 3, 6, and 24 hours was assessed by western blotting using a polyclonal rabbit anti‐MKP‐1 antibody (1:1000). To determine the role of MKP‐1 in regulating the action of ATRA on MAPKs, we examined whether any observed inhibition of MAPKs by ATRA could be prevented by the protein phosphatase inhibitor sodium orthovanadate (SV), a potent inhibitor of protein tyrosine phosphatases, which include MKP‐1.31,32 The influence of this inhibitor on PSC function (cell proliferation and extracellular matrix protein expression) was also assessed. PSCs were treated with 10 µM ATRA in the presence or absence of 1 µM SV for 48 hours. At the end of the incubation period, cell counts were performed using a haemocytometer and cell lysates were collected for assessment of MAPK activation and extracellular matrix protein expression by western blotting, as described above.

Treatment of freshly isolated PSCs with retinol

To determine whether retinol could prevent/retard the transition of freshly isolated (quiescent) PSCs to their activated phenotype, freshly isolated cells were incubated in IMDM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in the presence or absence of 10 µM retinol for five days. Medium was changed every 24 hours. At the end of the incubation period cell lysates were collected and expression of α‐SMA and fibronectin was assessed as described above.

Statistics

Results are expressed as mean (SEM); n represents the number of individual PSC preparations. Data were analysed using repeated measures analysis of variance.33 Fisher's protected least significant difference was used for comparison of individual groups provided the F test was significant.33,34 Analyses were performed using the Statview II statistical software package.

Results

Expression of retinol dehydrogenase II and retinoic acid receptors in PSCs

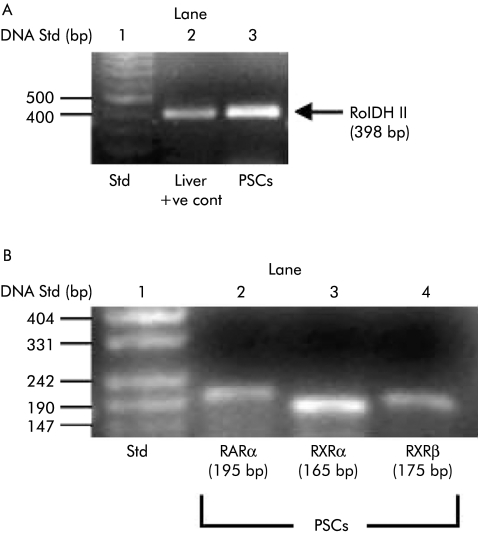

Using RT‐PCR, RolDH II, RARα, RXRα, and RXRβ expression was observed in PSCs (fig 1A, 1B, n = 3 separate cell preparations). PCR products were 398 bp, 195 bp, 165 bp, and 175 bp, respectively, in agreement with previous reports.26,27

Figure 1 (A, B) Expression of retinol dehydrogenase II (RolDH II), retinoic acid receptor (RAR), and retinoid X receptor (RXR) in pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs). (A) Total RNA was extracted from three separate cell preparations and analysed for RolDH II expression by reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR). An RNA ladder was run in lane 1 (Std) to determine the size of the PCR products observed. Lane 2 contained rat liver cDNA as a positive control. Lane 3 contained a PCR product for RolDH II from rat PSCs. Cont, control. (B) RARα, RXRα, and RXRβ expression was analysed in total RNA obtained from three separate cell preparations by RT‐PCR. Lane 1 contained an RNA ladder (Std) to determine the size of the PCR products observed. Lanes 2, 3, and 4 contained PCR products for RARα, RXRα, and RXRβ from rat PSCs.

Retinol and its metabolites ATRA and 9‐RA induce PSC quiescence

Cell proliferation

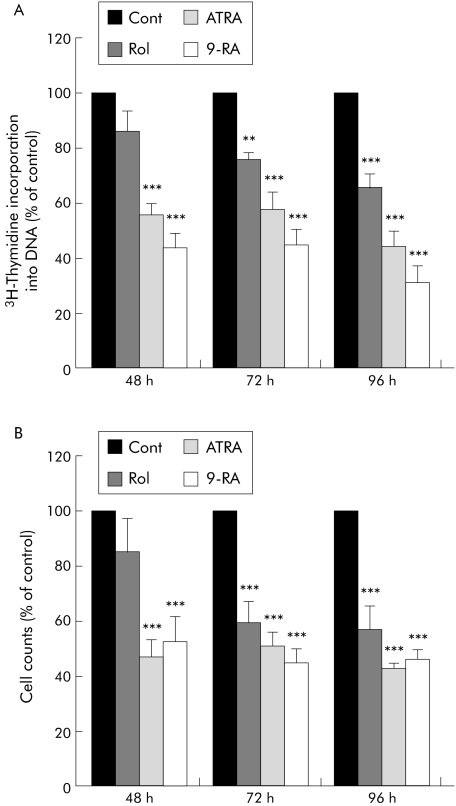

Retinol, ATRA, and 9‐RA reduced the proliferation of culture activated PSCs (n = 4 separate cell preparations), as assessed by thymidine incorporation into cellular DNA as well as by direct cell counts. There was a significant reduction after 72 hours of incubation with retinol and this effect was sustained over 96 hours (fig 2). Proliferation was also significantly reduced in the presence of ATRA and 9‐RA (fig 2). Notably, this reduction was observed at an earlier time point (48 hours) than that produced by retinol and this effect was sustained over 96 hours. We confirmed that the observed reduction in PSC proliferation was not due to cytotoxicity of retinol, ATRA, or 9‐RA, as evaluated by phase contrast microscopy and trypan blue exclusion studies (results not shown).

Figure 2 Effect of retinol and its metabolites on pancreatic stellate cell (PSC) proliferation. (A) [3H] thymidine incorporation studies and (B) cell count data demonstrating that incubation of PSCs with retinol (Rol) decreased PSC proliferation significantly when compared with controls (Cont) after 72 hours and that this effect was sustained over 96 hours. All‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and 9‐cis retinoic acid (9‐RA) also significantly decreased PSC proliferation after 48 hours when compared with controls and this effect was sustained over 96 hours (n = 3 separate cell preparations; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

α‐SMA expression

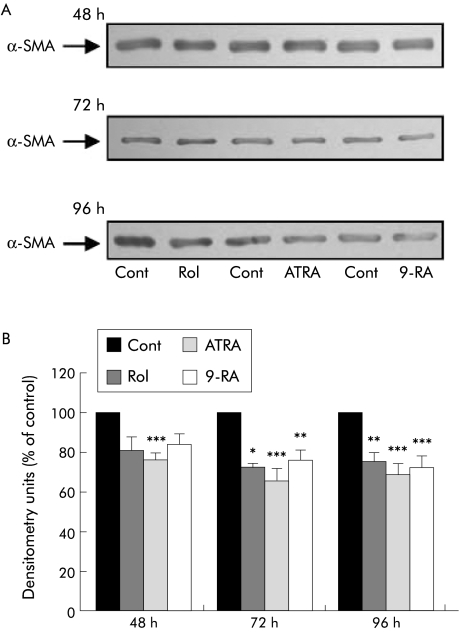

Quiescence of PSCs after incubation with retinol (n = 3 separate cell preparations) was also demonstrated by significantly reduced α‐SMA expression after 72 hours, an effect that was sustained over 96 hours (fig 3). Similar results were obtained with ATRA and 9‐RA (fig 3). ATRA was also associated with reduced α‐SMA expression at the earlier time point of 48 hours.

Figure 3 Effect of retinol and its metabolites on α smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA) expression in pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs). (A) Representative western blots showing α‐SMA expression in PSCs incubated with culture medium alone (Cont), retinol (Rol), all‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA), or 9‐cis retinoic acid (9‐RA) for 48, 72, and 96 hours. (B) Densitometry analysis of all western blots showing a significant decrease in α‐SMA expression at 72 and 96 hours in PSCs treated with Rol and at 48, 72, and 96 hours in PSCs treated with ATRA, compared with controls (n = 3 separate cell preparations; *p<0.02, **p<0.03, ***p<0.01).

Extracellular matrix protein expression

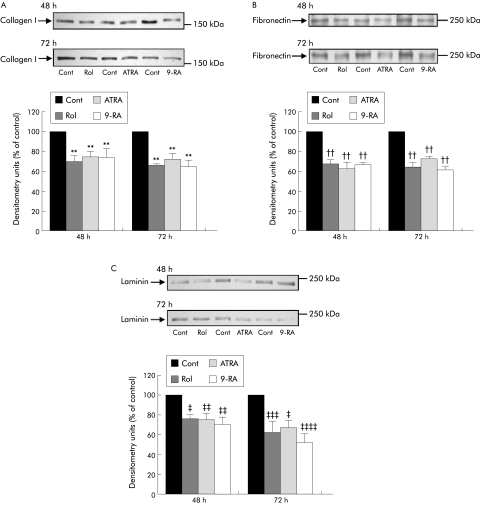

Extracellular matrix protein expression was significantly reduced in PSCs exposed to retinol or its metabolites (n = 3 separate cell preparations; fig 4A–C). After 48 hours of incubation, retinol significantly decreased collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin expression and this effect was sustained over 72 hours. Similar results were obtained for ATRA and 9‐RA.

Figure 4 (A–C) Effect of retinol and its metabolites on extracellular matrix protein expression in culture activated pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs). Representative western blots and densitometry analysis showing a significant decrease in expression of (A) collagen I, (B) fibronectin, and (C) laminin after treatment with retinol (Rol), all‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA), or 9‐cis retinoic acid (9‐RA) for 48 and 72 hours compared with controls (Cont). (n = 3 separate cell preparations; **p<0.005 for collagen I; ††p<0.001 for fibronectin; ‡p<0.004, ‡‡p<0.005, ‡‡‡p<0.003, ‡‡‡‡p<0.001 for laminin).

Retinol and its metabolites ATRA and 9‐RA influence MAPK activation in PSCs

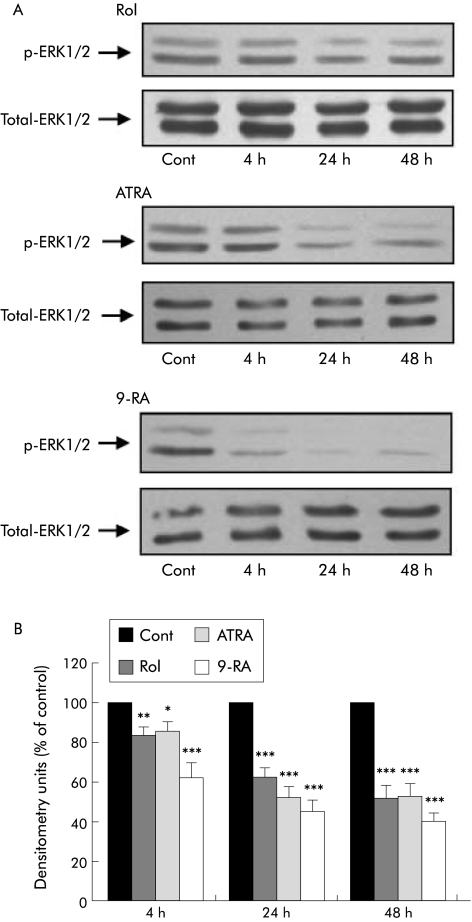

ERK1/2 activation

Incubation of PSCs with retinol (n = 4 separate cell preparations) caused a significant decrease in ERK1/2 activation at 4 hours; this decrease was sustained over 48 hours (fig 5). Similarly, ERK1/2 activation was reduced in the presence of ATRA and 9‐RA (fig 5). Western blotting of control and treated cell lysates for total ERK demonstrated that total ERK expression was unchanged by retinol, ATRA, and 9‐RA treatment. (Densitometry data expressed as per cent of control (mean (SEM)): at 4 h retinol 100.5 (5.8), ATRA 99.6 (4.6); 9‐RA 93.7 (3.6); at 24 h retinol 96.7 (9.2), ATRA 92.0 (8.9); 9‐RA 102.7 (5.1); at 48 h retinol 107.75 (10.6), ATRA 111.5 (6.5); 9‐RA 105.0 (7.2).) Thus these compounds appear to have a specific effect on ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Figure 5 Effect of retinol and its metabolites on activation of extracellular regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) in culture activated pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs). (A) Representative western blots showing ERK1/2 activation (p‐ERK1/2) and total ERK1/2 expression in PSCs incubated with retinol (Rol), all‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA), or 9‐cis retinoic acid (9‐RA) for 4, 24, and 48 hours. Cont, control. (B) Densitometry analysis of all western blots showing a significant decrease in ERK1/2 activation in PSCs treated with Ro), ATRA, or 9‐RA after 4, 24, and 48 hours compared with controls (n = 4 separate cell preparations; *p<0.04, **p<0.02, ***p<0.001). Rol, ATRA, or 9‐RA treatment had no significant effect on total ERK1/2 levels in PSCs.

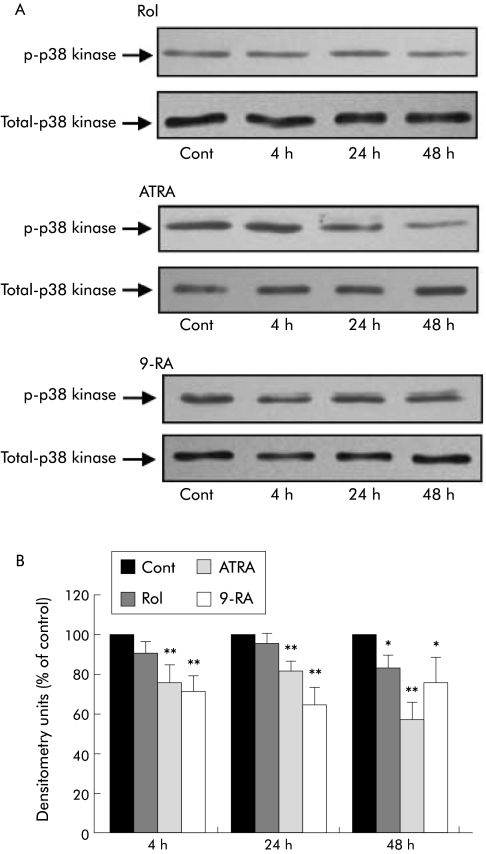

p38 kinase activation

Retinol significantly decreased p38 kinase activation after 48 hours of incubation (n = 4 separate cell preparations; fig 6). Both ATRA and 9‐RA also significantly reduced p38 kinase activation. However, this reduction was observed at the earlier time points of 4 and 24 hours and was sustained over 48 hours (fig 6). Total p38 kinase expression was unchanged by the treatments. (Densitometry data expressed as per cent of control (mean (SEM)): at 4 h retinol 102.8 (3.9), ATRA 94.2 (3.96); 9‐RA 90.57 (4.8); at 24 h retinol 93.07 (2.8), ATRA 98.6 (0.48); 9‐RA 99.2 (2.8); at 48 h retinol 90.55 (4.86), ATRA 95.4 (3.0); 9‐RA 102.6 (5.8).)

Figure 6 Effect of retinol and its metabolites on p38 kinase activation in culture activated pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs). (A) Representative western blots showing p38 kinase activation in PSCs incubated with retinol (Rol), all‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA), or 9‐cis retinoic acid (9‐RA) for 4, 24, and 48 hours. Cont, control. (B) Densitometry analysis of all western blots showing a significant decrease in p38 kinase activation in PSCs treated with Rol after 48 hours compared with controls. Treatment with ATRA or 9‐RA also resulted in a significant decrease in p38 kinase activation after 4 hours and was sustained after 48 hours compared with controls (n = 4 separate cell preparations; *p<0.02, **p<0.01). Rol, ATRA, or 9‐RA treatment had no significant effect on total p38 kinase levels in PSCs.

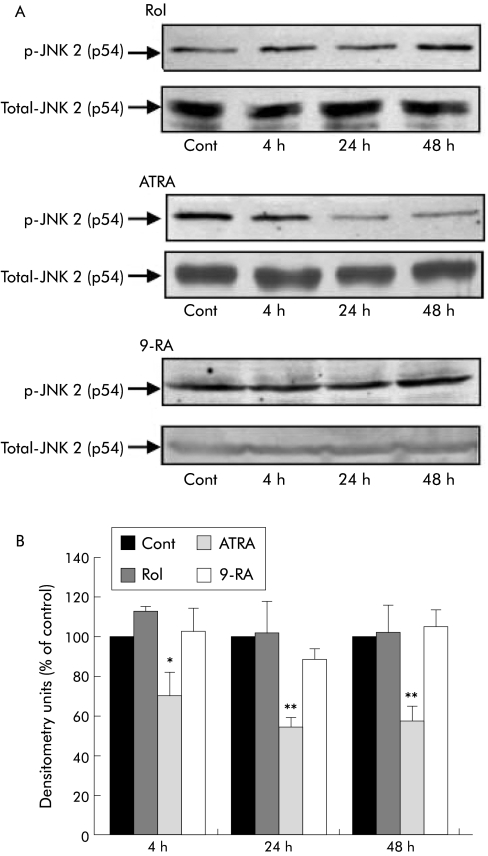

JNK activation

In contrast with the effect on ERK and p38 kinase activation, incubation of PSCs with retinol or 9‐RA had no effect on JNK 2 (p54) activation (n = 4 separate cell preparations; fig 7). However, ATRA significantly decreased JNK 2 (p54) activation after 4 hours and this decrease was sustained over 48 hours (fig 7). Total JNK expression was not affected by retinol, ATRA, or 9‐RA treatment. (Densitometry data expressed as per cent of control (mean (SEM)): at 4 h retinol 95.4 (10.0), ATRA 89.3 (8.7); 9‐RA 103.7 (6.9); at 24 h retinol 123.8 (11.5), ATRA 89.7 (11.8); 9‐RA 100.6 (9.9); at 48 h retinol 117.3 (13.4), ATRA 96.5 (2.8); 9‐RA 98.1 (3.3).)

Figure 7 Effect of retinol and its metabolites on c‐Jun N terminal kinase (JNK) activation in culture activated pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs). (A) Representative western blots showing JNK activation in PSCs incubated with retinol (Rol), all‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA), or 9‐cis retinoic acid (9‐RA) for 4, 24, and 48 hours. Cont, control. (B) Densitometry analysis of all western blots showing a significant decrease in JNK 2 (p54) activation after 4, 24, and 48 hours of treatment with ATRA compared with controls (n = 3 separate cell preparations; *p<0.01, **p<0.005). Both Rol and 9‐RA had no effect on JNK 2 (p54) activation. Total JNK 2 levels were unchanged by Rol, ATRA, or 9‐RA treatment.

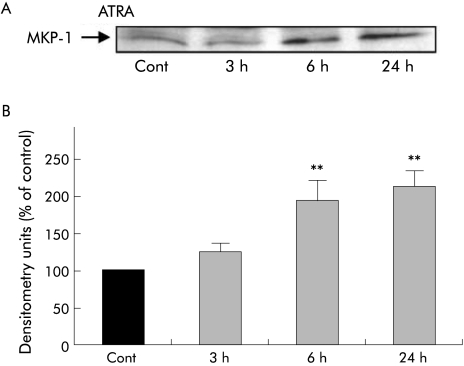

Effect of retinol, ATRA, and 9‐RA on MKP‐1 expression

ATRA significantly increased MKP‐1 expression in PSCs (n = 3 separate cell preparations) at 6 hours and this increase was sustained over 24 hours (fig 8). In contrast, retinol and 9‐RA had no effect on MKP‐1 expression (results not shown).

Figure 8 Effect of all‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA) on mitogen activated phosphatase 1 (MKP‐1) expression in culture activated pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs). (A) Representative western blot showing MKP‐1 expression in PSCs incubated with culture medium alone (Cont) or ATRA for 3, 6, and 24 hours. (B) Densitometry analysis of western blots showing a significant increase in MKP‐1 expression after 6 hours of treatment with ATRA; this effect was sustained over 24 hours compared with controls (n = 3 separate cell preparations; **p<0.005). Both retinol and 9‐cis retinoic acid had no effect on MKP‐1 expression (data not shown).

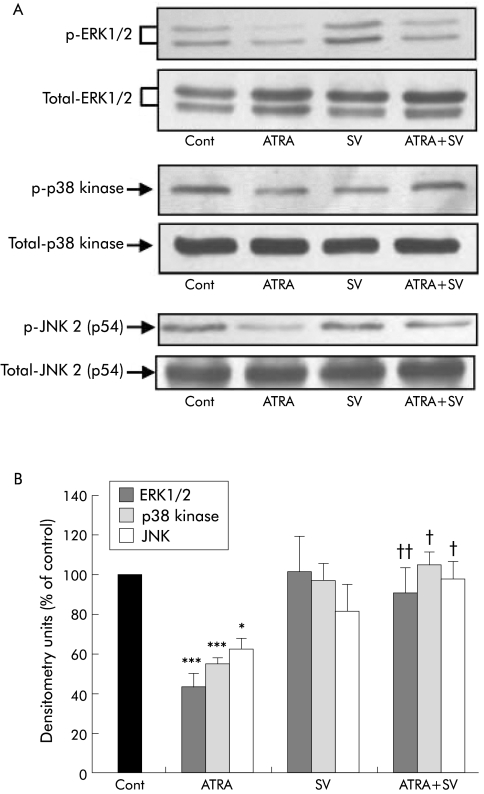

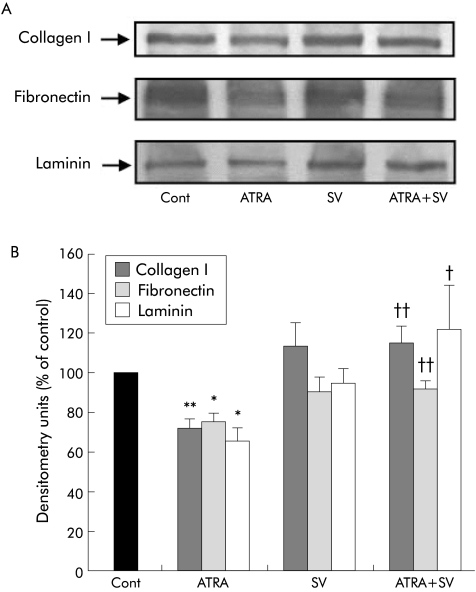

Effect of the protein phosphatase inhibitor sodium orthovanadate on MAPK expression, cell proliferation, and extracellular matrix protein expression in ATRA treated PSCs

To confirm whether MKP‐1 plays a role in mediating the effect of ATRA on MAPK activation in PSCs, cells were treated with the protein phosphatase inhibitor SV (n = 3 separate cell preparations). As shown in fig 9, the ATRA induced decrease in activation of ERK1/2, p38 kinase, and JNK 2 was completely prevented in the presence of SV, suggesting that MKP‐1 may mediate the ATRA induced inhibition of MAPK activation. SV treatment of PSCs also prevented the ATRA induced decrease in: (i) PSC proliferation (data expressed as per cent of control (mean (SEM)): control 100, ATRA 44.74 (8.72) (p<0.01 ATRA v control), SV 85.35 (16.5), ATRA+SV 98.03 (26.8) (p<0.01 ATRA v control)) and (ii) collagen I, fibronectin and laminin expression (fig 10), further supporting the concept that the effects of ATRA on PSC function may be mediated via the MAPK pathway. Trypan blue exclusion studies confirmed cell viability in the presence of SV (results not shown).

Figure 9 Effect of sodium orthovanadate (SV) on mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation in all‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA) treated cells. Representative western blots and densitometry analysis showing a significant decrease in activation of all three classes of MAPK in pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) treated with ATRA for 24 hours (ERK1/2, extracellular regulated kinases 1 and 2; p38 kinase; and JNK 2, c‐Jun N terminal kinase 2). This decrease was prevented in the presence of SV (*p<0.02, ***p<0.001, ATRA v control (Cont); †p<0.02, ††p<0.003, ATRA v ATRA+SV; n = 3 separate cell preparations). Total MAPK levels were unchanged by the treatments.

Figure 10 Effect of sodium orthovanadate (SV) on all‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA) induced inhibition of extracellular matrix protein expression in pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs). Representative western blots and densitometry analysis showing a significant decrease in collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin expression in PSCs treated with ATRA for 48 hours and prevention of this decrease in the presence of SV (*p<0.02, **p<0.03 ATRA v control (Cont); †p<0.04, ††p<0.02, ATRA v ATRA+SV; n = 3 separate cell preparations).

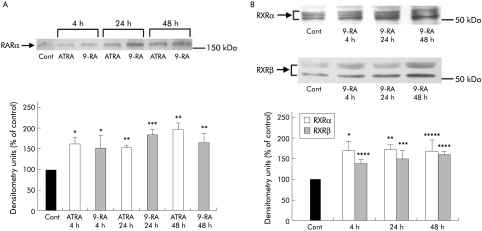

Effect of ATRA and 9‐RA on RAR and RXR protein expression

After 4 hours of incubation, both ATRA and 9‐RA significantly increased RARα protein expression in PSCs (n = 3 separate cell preparations) and this effect was sustained over 24 and 48 hours (fig 11A). 9‐RA also increased expression of RXRα and RXRβ at 4, 24, and 48 hours of incubation (fig 11B).

Figure 11 (A, B) Effect of all‐trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and 9‐cis retinoic acid (9‐RA) on retinoic acid receptor (RAR) and retinoid X receptor (RXR) receptor expression in culture activated pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs). (A) Representative western blots and densitometry analysis showing a significant increase in RARα protein expression in PSCs treated with ATRA for 4, 24, and 48 hours (*p<0.04, **p<0.03, ***p<0.02; n = 3 separate cell preparations). Cont, control. (B) Representative western blots and densitometry analysis showing a significant increase in RXRα and RXRβ protein expression in PSCs treated with 9‐RA for 4, 24, and 48 hours (*p<0.03, **p<0.02, ***p<0.003, ****p<0.004, *****p<0.005; n = 3 separate cell preparations). Note that both RXRα and RXRβ were represented by a number of protein bands with increased intensity, suggesting the presence of multiple activated isoforms.

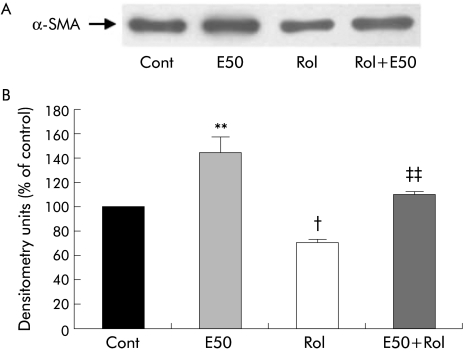

Effect of retinol on ethanol induced PSC activation

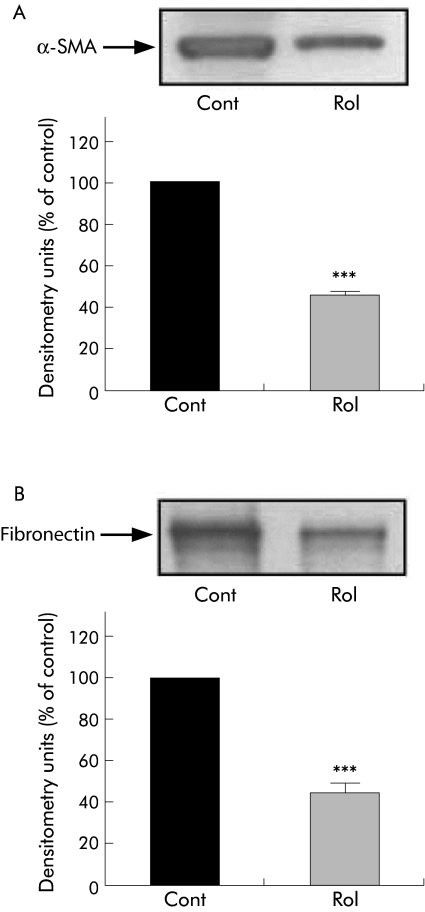

α‐SMA expression

In order to determine whether retinol supplementation could prevent ethanol induced PSC activation, α‐SMA expression was assessed (n = 3 separate cell preparations; fig 12). As expected, ethanol alone significantly increased α‐SMA expression confirming our previously published results.3,17 Retinol alone significantly reduced α‐SMA expression confirming our results described in fig 3. Importantly, retinol also significantly reduced α‐SMA expression in PSCs treated with ethanol. Of particular interest was the finding that in the presence of ethanol, retinol was unable to fully exert its inhibitory effect when compared with retinol alone (compare Rol with E50+Rol, fig 12).

Figure 12 Effect of retinol on ethanol induced α smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA) expression in pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs). (A) Representative western blot showing α‐SMA expression in PSCs incubated with culture medium alone (Cont) or with 50 mM ethanol (E50) in the presence or absence of retinol (Rol) for five days. (B) Densitometry analysis of western blots showing a significant increase in α‐SMA expression in PSCs when treated with ethanol (n = 3 separate cell preparations; **p<0.01) compared with controls. Rol significantly decreased basal α‐SMA expression (n = 3 separate cell preparations; †p<0.02 Rol v Cont) and prevented the ethanol induced increase in α‐SMA expression in PSCs (n = 3 separate cell preparations; ††p<0.01 E50 v E50+Rol).

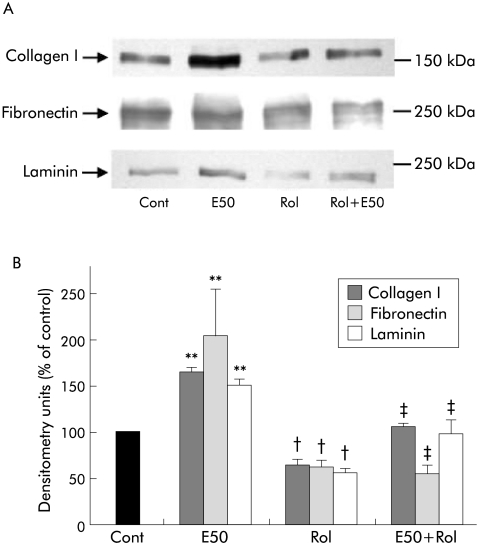

Extracellular matrix protein expression

As illustrated in fig 13, retinol significantly inhibited expression of all three extracellular matrix proteins in PSCs (n = 3 separate cell preparations) and also prevented the ethanol induced increase in collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin expression in the cells. Interestingly, as with α‐SMA expression, retinol was unable to fully exert its inhibitory effect on collagen I and laminin expression in the presence of ethanol, compared with retinol alone.

Figure 13 Effect of retinol on ethanol induced extracellular matrix protein synthesis in pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs). (A) Representative western blot showing collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin expression in PSCs incubated with culture medium alone (Cont) or with 50 mM ethanol (E50) in the presence or absence of retinol (Rol) for five days. (B) Densitometry analysis of western blots showing a significant increase in collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin expression in PSCs treated with ethanol compared with controls (n = 3 separate cell preparations; **p<0.005 E50 v Cont). Rol significantly decreased basal collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin levels (n = 3 separate cell preparations; †p<0.05 Rol v Cont) and prevented the ethanol induced increase in extracellular matrix protein expression (n = 3 separate cell preparations; ‡p<0.05 E50 v E50+Rol).

Effect of retinol on freshly isolated PSCs

Incubation of freshly isolated PSCs with retinol for five days significantly decreased expression of both α‐SMA and fibronectin in cells compared with controls (fig 14A, B).

Figure 14 Effect of retinol on freshly isolated pancreatic stellate cell (PSC) activation. Representative western blots and densitometry analysis showing a significant decrease in expression of (A) α smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA) and (B) fibronectin in freshly isolated PSCs treated with retinol (Rol) for five days compared with controls (Cont) (n = 4 separate cell preparations; ***p<0.001).

Discussion

This study provides novel data demonstrating that vitamin A (retinol) induces quiescence in both freshly isolated and culture activated PSCs. We have also shown that the metabolites of vitamin A (ATRA and 9‐RA) inhibit the activation of culture activated PSCs. Notably, we have found that the above effects are associated with a significant decrease in activation of all three classes of MAPKs, suggesting that vitamin A induced quiescence is mediated via the MAPK pathway. Another novel finding of this study (of relevance to alcohol induced fibrosis) is the prevention of ethanol induced PSC activation by retinol. To the best of our knowledge, this aspect has not been previously studied in pancreatic or hepatic stellate cells.

The present study has also provided evidence indicating that PSCs possess the ability to convert retinol into its active metabolites. We have shown that cultured PSCs express the enzyme RolDH II, an enzyme which is essential for the conversion of cellular retinol to retinoic acid. Our findings also suggest the presence of a functional retinoic acid signalling pathway in PSCs. We have identified mRNA for RAR and RXRs in cells and, moreover, have found that expression of RAR and RXR proteins is induced by their ligands ATRA and 9‐RA. The observed induction of receptor protein expression by their ligands in PSCs concurs with a previous report in cardiomyocytes, showing that both RAR and RXR are transcriptionally activated by ATRA and 9‐RA.35

The signalling pathways responsible for regulating PSC activation have been the focus of much interest in recent years, as therapeutic targeting of relevant signalling molecules may enable inhibition of PSC activation and prevention of fibrogenesis. Studies by our group and others have demonstrated that all three classes (ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 kinase) of the MAPK pathway play an important role in mediating PSC activation on exposure to profibrogenic factors.17,18,19 The ERK1/2 pathway has been shown to mediate PSC proliferation by increasing the activity of the transcription factor AP‐1.19 Recently, our group and others have shown that the p38 kinase pathway plays a major role in mediating α‐SMA expression in culture activated and ethanol treated PSCs.17,36 Masamune and colleagues18,37 reported that both p38 kinase and JNK play an important role in mediating extracellular matrix protein synthesis in PSCs. Given the above, it would be reasonable to speculate that inhibition of PSC activation by vitamin A may be mediated by inhibition of the MAPK pathway. The results of our study support this concept. We have demonstrated for the first time that retinol, ATRA, and 9‐RA significantly decrease activation of ERK1/2 and p38 kinase in culture activated PSCs after 4 hours of incubation and this decrease was sustained over 48 hours. In addition, ATRA (but not retinol or 9‐RA) significantly decreased JNK 2 (p54) activation at 4, 24, and 48 hours. Our results with ATRA concur with those reported in human bronchial cells and hepatocytes.25,38 Both ERK1/2 and JNK MAPKs are known to regulate the activity of the transcription factor AP‐1, which in turn is known to be an essential factor for the regulation of cell proliferation.21 On activation, AP‐1 binds to a DNA sequence motif in target genes, thereby regulating their expression.39 A number of studies in other cell types have shown that increased AP‐1 activity is essential in regulating cell proliferation (see review).40 It is of interest to note that on exposure to vitamin A, AP‐1 activity is decreased in a number of different cell types, and this is thought to be one of the mechanisms whereby vitamin A inhibits cell proliferation.41

The mechanisms of MAPK inhibition (inactivation) by vitamin A are not yet determined. While activation of MAPK depends on phosphorylation of its tyrosine and threonine residues by upstream kinases, recent studies indicate that inactivation of MAPK is secondary to dephosphorylation via MKPs.22 MKP‐1 has been shown to inactivate all three classes of MAPKs.23,24 Interestingly, studies in other cell types have reported that treatment with vitamin A increases expression of MKP‐1 which in turn results in a decrease in MAPK activity.25,31,42 The current study has demonstrated that ATRA (but not retinol or 9‐RA) induces expression of MKP‐1 in PSCs. This induction is evident after 6 hours of incubation and is sustained over 24 hours. We have further demonstrated that the protein phosphatase inhibitor SV (known to inhibit phosphatases such as MKP‐1) prevents the inhibition of MAPK activation in PSCs treated with ATRA. These findings support the concept that an increase in MKP‐1 activity may play a role in the observed decrease in MAPK activation in PSCs exposed to ATRA. The mechanisms responsible for the retinol and 9‐RA induced decrease in MAPK activation are unclear (given that these compounds did not increase MKP‐1 activity in PSCs). It is possible that these compounds induce the activity of other phosphatases of the MAPK phosphatase family, as has been reported by Palm‐Leis and colleagues35 in cardiomyocytes.

It is now generally accepted that ethanol induced PSC activation plays a major role in alcoholic pancreatic fibrosis.3 In view of our findings that retinol induces quiescence of PSCs in culture, we examined the effect of retinol on ethanol treated PSCs. Our results have shown that retinol prevents ethanol induced PSC activation, as evidenced by a significant decrease in α‐SMA expression and, more importantly, a significant decrease in the expression of the extracellular matrix proteins collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin which are major components of fibrous tissue. In the course of these studies, an interesting observation was made with respect to the effect of retinol on PSC activation in the presence and absence of ethanol. In the presence of ethanol, retinol was found to be unable to exert its full inhibitory effect on α‐SMA, collagen I, and laminin expression compared with retinol alone (see fig 12 Rol v Rol+E50 for α‐SMA expression and fig 13 Rol v Rol+E50 for collagen I and laminin expression). One possible explanation for this could be the competitive inhibition of retinol metabolism by ethanol, as the enzymes RolDH and ADH can use both retinol and ethanol as substrates.26,43 There is evidence for the presence of both of these enzymes in PSCs. The current study has demonstrated expression of mRNA for RolDH in PSCs, while previous studies by our group have demonstrated ADH enzyme activity (inducible after exposure to ethanol) in PSCs.3 A decrease in retinol metabolism in ethanol treated PSCs would lead to lower retinoic acid levels in these cells compared with PSCs treated with retinol alone.

In conclusion, this study is the first to demonstrate that vitamin A and/or its metabolites ATRA and 9‐RA induce quiescence in both freshly isolated and culture activated PSCs. Induction of PSC quiescence is associated with a decrease in activation of all three classes of MAPKs. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that retinol supplementation prevents ethanol induced activation of PSCs. These findings suggest that vitamin A may be a potentially useful antifibrotic agent in chronic pancreatitis via its ability to inhibit PSC activation and consequently reduce their synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins.

Acknowledgements

Studies described in this manuscript were supported by grants from the Department of Veterans' Affairs Australia and the Health Research Foundation Sydney South West. Joshua A McCarroll was supported from a GlaxoWellcome/Gastroenterological Society of Australia Biomedical Postgraduate Research Scholarship and by a South Western Sydney Clinical School University of New South Wales Postgraduate Research Scholarship.

Abbreviations

ADH - alcohol dehydrogenase

ATRA - all‐trans retinoic acid

ECL - enhanced chemiluminescence

ERK1/2 - extracellular regulated kinases 1 and 2

HSCs - hepatic stellate cells

IMDM - Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium

JNK - c‐Jun N terminal kinase

MAPK - mitogen activated protein kinase

MKP‐1 - mitogen activated phosphatase 1

PSCs - pancreatic stellate cells

RALDH - retinaldehyde dehydrogenase

RAR - retinoic acid receptor

RXR - retinoid X receptor

RolDH - retinol dehydrogenase

Rol - retinol

9‐RA - 9‐cis retinoic acid

RT‐PCR - reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction

α‐SMA - α smooth muscle actin

SV - sodium orthovanadate

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.DiMagno E P, Layer P, Clain J E. Chronic pancreatitis. In: Go VLW, DiMagno EP, Gardner JD, et al, eds. The pancreas: biology, pathobiology and disease. New York: Raven Press, 1993665–706.

- 2.Apte M V, Haber P S, Applegate T L.et al Pancreatic stellate cells are activated by proinflammatory cytokines:implications for fibrogenesis. Gut 199944534–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apte M V, Phillips P A, Fahmy R G.et al Does alcohol directly stimulate pancreatic fibrogenesis? Studies with rat pancreatic stellate cells. Gastroenterology 2000118780–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider E, Schmid‐Kotsas A, Zhao J.et al Identification of mediators stimulating proliferation and matrix synthesis of rat pancreatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2001281C532–C543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apte M V, Haber P S, Applegate T L.et al Periacinar stellate shaped cells in rat pancreas—identification, isolation, and culture. Gut 199843128–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachem M G, Schneider E, Gross H.et al Identification, culture, and characterization of pancreatic stellate cells in rats and humans. Gastroenterology 1998115421–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Love J M, Gudas L J. Vitamin A, differentiation and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19946825–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambon P. A decade of molecular biology of retinoic acid receptors. FASEB J 199610940–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ottonello S, Scita G, Mantovani G.et al Retinol bound to cellular retinol‐binding protein is a substrate for cytosolic retinoic acid synthesis. J Biol Chem 199326827133–27142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duester G. Families of retinoid dehydrogenases regulating vitamin A function: Production of visual pigment and retinoic acid. Eur J Biochem 20002674315–4324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mangelsdorf D J, Borgmeyer U, Heyman R A.et al Characterization of three rxr genes that mediate the action of 9‐cis retinoic acid. Genes Dev 19926329–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohata M, Lin M, Satre M.et al Diminished retinoic acid signaling in hepatic stellate cells in cholestatic liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol 1997272G589–G596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaster R, Hilgendorf I, Fitzner B.et al Regulation of pancreatic stellate cell function in vitro: Biological and molecular effects of all‐trans retinoic acid. Biochem Pharmacol 200366633–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X D, Liu C, Chung J.et al Chronic alcohol intake reduces retinoic acid concentration and enhances ap‐1 (c‐jun and c‐fos) expression in rat liver. Hepatology 199828744–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deltour L, Ang H L, Duester G. Ethanol inhibition of retinoic acid synthesis as a potential mechanism for fetal alcohol syndrome. FASEB J 1996101050–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han C L, Liao C S, Wu C W.et al Contribution to first‐pass metabolism of ethanol and inhibition by ethanol for retinol oxidation in human alcohol dehydrogenase family—implications for etiology of fetal alcohol syndrome and alcohol‐related diseases. Eur J Biochem 199825425–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCarroll J A, Phillips P A, Park S.et al Pancreatic stellate cell activation by ethanol and acetaldehyde: Is it mediated by the mitogen‐activated protein kinase signaling pathway? Pancreas 200327150–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masamune A, Kikuta K, Satoh M.et al Alcohol activates activator protein‐1 and mitogen‐activated protein kinases in rat pancreatic stellate cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 200230236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaster R, Sparmann G, Emmrich J.et al Extracellular signal regulated kinases are key mediators of mitogenic signals in rat pancreatic stellate cells. Gut 200251579–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopez‐Ilasaca M. Signaling from g‐protein‐coupled receptors to mitogen‐activated protein (MAP)‐kinase cascades. Biochem Pharmacol 199856269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gibson T.et al Mitogen‐activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: Regulation and physiological functions. Endocrine Rev 200122153–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haneda M, Sugimoto T, Kikkawa R. Mitogen‐activated protein kinase phosphatase: A negative regulator of the mitogen‐activated protein kinase cascade. Eur J Pharmacol 19993651–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun H, Charles C H, Lau L F.et al MKP‐1 (3CH134), an immediate early gene product, is a dual specificity phosphatase that dephosphorylates MAP kinase in vivo. Cell 199375487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franklin C C, Srikanth S, Kraft A S. Conditional expression of mitogen‐activated protein kinase phosphatase‐1, MKP‐1, is cytoprotective against UV‐induced apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998953014–3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung J, Chavez P R, Russell R M.et al Retinoic acid inhibits hepatic Jun N‐terminal kinase‐dependent signaling pathway in ethanol‐fed rats. Oncogene 2002211539–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sauvant P, Sapin V, Abergel A.et al Pav‐1, a new rat hepatic stellate cell line converts retinol into retinoic acid, a process altered by ethanol. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2002341017–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ulven S M, Natarajan V, Holven K B.et al Expression of retinoic acid receptor and retinoid x receptor subtypes in rat liver cells: Implications for retinoid signalling in parenchymal, endothelial, kupffer and stellate cells. Eur J Cell Biol 199877111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarroll J A, Phillips P A, Kumar R K.et al Pancreatic stellate cell migration: Role of the phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase(PI3‐kinase) pathway. Biochem Pharmacol 2004671215–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lugea A, Gukovsky I, Gukovskaya A S.et al Nonoxidative ethanol metabolites alter extracellular matrix protein content in rat pancreas. Gastroenterology 20031251845–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reif S, Lang A, Lindquist J N.et al The role of focal adhesion kinase‐phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase‐akt signaling in hepatic stellate cell proliferation and type I collagen expression. J Biol Chem 20032788083–8090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Q, Konta T, Furusu A.et al Transcriptional induction of mitogen‐activated protein kinase phosphatase 1 by retinoids. Selective roles of nuclear receptors and contribution to the antiapoptotic effect. J Biol Chem 200227741693–41700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee H Y, Sueoka N, Hong W K.et al All‐trans‐retinoic acid inhibits Jun N‐terminal kinase by increasing dual‐specificity phosphatase activity. Mol Cell Biol 1999191973–1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snedecor G, Cochran W.Statistical methods, 8th edn. Ames, IO: Iowa State University Press 1989

- 34.Feldman D J, Hofmann R, Gagnon J.et alStatview ii. Berkeley, CA: Abacus Concepts Inc, 1987

- 35.Palm‐Leis A, Singh U S, Herbelin B S.et al Mitogen‐activated protein kinases and mitogen‐activated protein kinase phosphatases mediate the inhibitory effects of all‐trans retinoic acid on the hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem 200427954901–54917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masamune A, Satoh M, Kikuta K.et al Inhibition of p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase blocks activation of rat pancreatic stellate cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 20033048–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masamune A, Kikuta K, Suzuki N.et al A c‐jun NH2‐terminal kinase inhibitor SP600125 (anthra[1,9‐CD]pyrazole‐6 (2H)‐one) blocks activation of pancreatic stellate cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004310520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee H Y, Walsh G L, Dawson M I.et al All‐trans‐retinoic acid inhibits Jun N‐terminal kinase‐dependent signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 19982737066–7071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karin M, Liu Z, Zandi E. Ap‐1 function and regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19979240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiu R, Boyle W J, Meek J.et al The c‐fos protein interacts with c‐jun/AP‐1 to stimulate transcription of AP‐1 responsive genes. Cell 198854541–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schule R, Rangarajan P, Yang N.et al Retinoic acid is a negative regulator of AP‐1‐responsive genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991886092–6096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee J C, Kassis S, Kumar S.et al P38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase inhibitors—mechanisms and therapeutic potentials. Pharmacol Ther 199982389–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Molotkov A, Duester G. Retinol/ethanol drug interaction during acute alcohol intoxication in mice involves inhibition of retinol metabolism to retinoic acid by alcohol dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem 200227722553–22557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]