Summary

Chemoprevention has been considered as a possible approach for cancer prevention. A significant effort has been made in the development of novel drugs for both cancer prevention and treatment over the past decade. Recent epidemiological studies and clinical trials indicate that long term use of aspirin and similar agents, also called non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), can decrease the incidence of certain malignancies, including colorectal, oesophageal, breast, lung, and bladder cancers. The best known targets of NSAIDs are cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, which convert arachidonic acid to prostaglandins (PGs) and thromboxane. COX‐2 derived prostaglandin E2(PGE2) can promote tumour growth by binding its receptors and activating signalling pathways which control cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis, and/or angiogenesis. However, the prolonged use of high dosages of COX‐2 selective inhibitors (COXIBs) is associated with unacceptable cardiovascular side effects. Thus it is crucial to develop more effective chemopreventive agents with minimal toxicity. Recent efforts to identify the molecular mechanisms by which PGE2 promotes tumour growth and metastasis may provide opportunities for the development of safer strategies for cancer prevention and treatment.

Introduction

The most effective treatments for cancer, including various combinations of surgical resection, radiation, and/or chemotherapy, depend on the detection of cancer at a very early stage. Unfortunately, it has not been possible to identify all individuals who are at the highest risk for developing cancer. Most patients present to their physician with advanced cancer when standard treatment regimens for solid malignancies result in a much lower five year survival. It is generally agreed that an effective way to control cancer is to find better ways of preventing it. Chemopreventive approaches are definitely worth considering for healthy persons who have a strong family history of cancer or those who are particularly susceptible for other reasons. One promising group of compounds with cancer preventive activity includes NSAIDS.

A large body of evidence from population based studies, case control studies, and clinical trials indicate that regular use of NSAIDs over a 10–15 year period reduces the relative risk of developing colorectal cancer by 40–50%.1 Furthermore, use of NSAIDs leads to regression of pre‐existing adenomas in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).2 As many other human cancers are reported to have elevated levels of COX‐2 and overproduce PGs, there is great interest in evaluating the role of NSAIDs for prevention and treatment strategies for other cancers such as breast, stomach, pancreas, urinary tract, lung, and prostate. However, the prolonged use of NSAIDs is associated with side effects such as nausea, dyspepsia, gastritis, abdominal pain, peptic ulcer, gastrointestinal bleeding, and/or perforation of gastroduodenal ulcers.3 It was hypothesised that NSAIDs exert their anti‐inflammatory and antitumour effects through inhibition of the inducible COX‐2,4,5 while unwanted side effects of these drugs such as damage to the gastric mucosa and gastrointestinal bleeding are thought to arise from the inhibition of the constitutive COX‐1.6 This hypothesis led to the development of COXIBs, such as celecoxib, rofecoxib, and valdecoxib. Indeed, highly selective COX‐2 inhibitors retain the anti‐inflammatory and antitumour effects of the NSAIDs while not interfering with COX‐1 responsible for protection of the gastroduodenal mucosa from the effects of acid from the stomach.5,7,8,9 Therefore, these drugs were approved by the FDA, and as novel anti‐inflammatory agents their use is associated with about a 50% reduction in gastrointestinal toxicity. Moreover, these agents have some potential for use as chemopreventives.10,11,12 One of them, celecoxib, was approved in December 1999 by the FDA for use in the prevention of colorectal polyp formation of patients with FAP. Unexpectedly, the prolonged use of higher doses of COX‐2 selective inhibitors is associated with increased thrombotic events in humans.13,14,15 We know that this original hypothesis was overly simplistic because of our lack of knowledge of the importance of signalling pathways which are affected downstream of COX‐2. Thus it has become essential for us to understand how NSAIDs interfere with COX‐2 mediated cellular functions in both normal physiology and pathological conditions.

NSAID targets

Inflammation and cancer

NSAIDs are chemically distinct compounds that share a common therapeutic action. The best known of these are aspirin, ibuprofen, piroxicam, indomethacin, and sulindac. NSAIDs are generally prescribed to ameliorate symptoms associated with acute pain and chronic inflammatory diseases such as arthritis. Chronic inflammation caused by infections or autoimmune diseases is clearly associated with an increased cancer risk in a number of instances. For example, it has long been known that patients with persistent hepatitis B, Helicobacter pylori infections, or an immune disorder such as ulcerative colitis have a higher risk for the development of liver or gastrointestinal tract cancer. It has been estimated that chronic inflammation contributes to the development of approximately 15% of malignancies worldwide.16 The connection between inflammation and cancer further supports the concept that anti‐inflammatory drugs, NSAIDs, have antineoplastic activity.

COX dependent targets

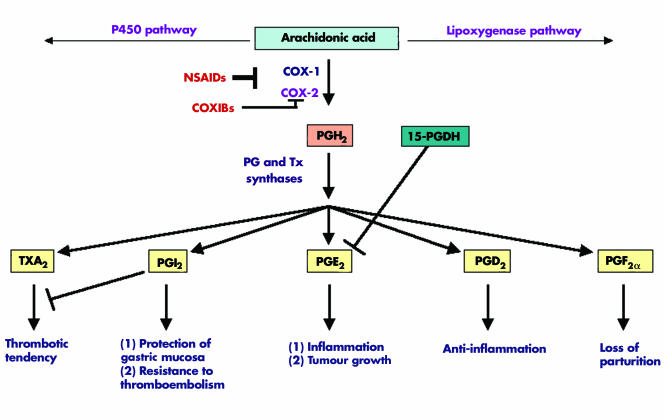

NSAIDs were shown to exert their anti‐inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic effects mainly by inhibiting COX, a key enzyme responsible for the biosynthesis of PGs from arachidonic acid.6 Aspirin is an irreversible inhibitor of COX through blocking the approach of arachidonic acid, while indomethacin, piroxicam, ibuprofen, and sulindac are competitive inhibitors for substrate binding. When COX converts arachidonic acid to PGs, the key regulatory step in this process is the enzymatic conversion of arachidonate to PGG2, which is then reduced to an unstable endoperoxide intermediate, PGH2. Specific PG synthases in turn metabolise PGH2 to at least five structurally related bioactive lipid molecules, including PGE2, PGD2, PGF2α, PGI2, and thromboxane A2(TxA2)17(fig 1).

Figure 1 Overview of prostaglandin (PG) synthesis and main functions. Arachidonic acid can be metabolised through three major pathways. In the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway, each COX‐2 derived prostaglandin (PGI2, PGE2, PGD2, PGF2α) or thromboxane A2 (TxA2) has its unique functions. NSAIDs, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs; COXIBs, COX‐2 selective inhibitors.

COX exists in two isoforms commonly referred to as COX‐1 and COX‐2. Although both COX‐1 and COX‐2 are upregulated in a variety of circumstances, normally COX‐1 is constitutively expressed in a broad range of cells and tissues. COX‐1 expression remains constant under most physiological or pathological conditions and its constitutive enzymatic activity is linked to renal function, gastric mucosal maintenance, stimulation of platelet aggregation, and vasoconstriction. For example, COX‐1 derived prostaglandins play a central role in many normal physiological processes. In the gut, COX‐1 derived PGI2(also called prostacyclin) produced by epithelial and stromal cells in subepithelial tissues plays a key role in the cytoprotection of gastric mucosal surfaces and the normal vasculature.18 COX‐1 has been shown to play an essential role in gastrulation in zebrafish and a reduction in COX‐1 results in posterior mesodermal defects during zebrafish development.19,20 In contrast, COX‐2 is an immediate early response gene and its expression is normally absent in most cells and tissues but it is highly induced in response to proinflammatory cytokines, hormones, and tumour promoters.21 Furthermore, COX‐2 derived PGE2 is a proinflammatory bioactive lipid and is the major prostaglandin produced in many human solid tumours, including cancer of the colon,22 stomach,23 and breast.24 Recent research has indicated that COX‐2 derived PGE2 is a key mediator of acute inflammatory responses,25,26 arthritis,27,28 and inflammatory bowel disease.29,30 Direct evidence supporting the notion that PGE2 promotes tumour growth comes from the following observations. PGE2 reversed NSAID induced adenoma regression in ApcMin mice.31 PGE2 significantly enhanced colon carcinogen induced tumour incidence and multiplicity in rats.32 Furthermore, our group recently reported that PGE2 accelerates intestinal adenoma growth in ApcMin mice.33

Although COX‐2 selective inhibitors suppress PGE2 production, the potential inhibition of endothelial cell derived COX‐2 activity and subsequent PGI2 production may promote platelet aggregation and lead to an increased risk of coronary thrombosis and stroke.34 As PGI2 antagonises thromboxane produced by platelets, inhibition of PGI2 may shift the homeostatic balance towards more TXA2 effects. In addition, PGI2 appears to be important in protecting cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress.35 Therefore, it will be important to develop chemopreventive agents that do not inhibit production of other prostanoids, such as the antithrombotic PGI2. Given that only PGE2 appears to be procarcinogenic, more selective pharmacological inhibition of PGE2 production downstream of COX‐2 may be superior and result in fewer side effects. To achieve this goal, researchers have been investigating precisely how PGE2 promotes tumour growth and its signalling pathways.

COX independent targets

Another explanation for the antitumour effects of NSAIDs recently emerged, based on studies showing that high doses of NSAIDs inhibit tumour cell growth and induce apoptosis through COX independent mechanisms by regulating several different targets,36 such as 15‐LOX‐1,37 a proapoptotic gene Par‐4,38 antiapoptotic gene Bcl‐XL,39 and nuclear factor κB (NFκB) signalling.40,41 In the above studies, higher NSAID concentrations may be impossible to achieve in vivo without significant toxicity. For example, the proapoptotic effects of NSAIDs seen at concentrations above 50 μM are most likely modulated through COX‐2 independent pathways. However, the best characterised biochemical target of NSAIDs at therapeutic concentrations remains the COX enzymes. It is likely that many of the chemopreventive effects of NSAIDs are carried out via inhibition of COX‐2.

PGE2 and cancer

PGE2 and its receptors play a predominant role in promoting cancer progression. The only other COX‐2 derived prostaglandin implicated in oncogenesis is TxA2, which was reported to promote angiogenesis.42 NSAIDs have been shown to inhibit PGE2 mediated processes that play essential roles in tumour progression, such as tumour cell proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and immunosuppression. Therefore, we will focus on modulation of PGE2 and its downstream targets that control these processes.

PGE2 regulation and its receptors

Steady state cellular levels of PGE2 depend on the relative rates of COX‐2/PGE synthase dependent biosynthesis and 15‐hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15‐PGDH) dependent degradation (fig 1). For example, cytosolic or microsomal PGE2 synthases can convert PGH2 to PGE2. Two cytosolic PGE2 synthases called cytosolic glutathione transferases (GSTM2‐2 and GSTM3‐3) catalyse the conversion of PGH2 to PGE2 in the human brain.43 The two microsomal PGE2 synthases characterised to date are mPGES1 and mPGES2. mPGES1 exhibits a higher catalytic activity than other PGES isomerases, indicating that it probably plays a key role in the synthesis of PGE2 from PGH2.44,45

15‐PGDH, a prostaglandin degrading enzyme, catalyses oxidisation of the 15(S)‐hydroxyl group of PGE2 to yield an inactive 15‐keto PGE2.46 Genetic deletion of 15‐Pgdh in mice leads to increased tissue levels of PGE2.47 Although 15‐PGDH may promote certain androgen sensitive prostate cancers,48 we and others recently reported that loss of expression of 15‐PGDH correlates with tumour formation, including colorectal cancer,49,50 lung,51 and transitional bladder cancer.52 Interestingly, NSAIDs have been shown to upregulate 15‐PGDH expression in colorectal and medullary thyroid cancers.49,53 Taken together, these studies suggest that loss expression of 15‐PGDH may contribute to tumour progression. The functional role of 15‐PDGH in promoting tumour growth is currently under investigation in several laboratories.

PGE2 exerts its cellular effects by binding to its cognate receptors (EP1‐4) that belong to the family of seven transmembrane G protein coupled rhodopsin‐type receptors. The central role of PGE2 in tumorigenesis has been further confirmed through homozygous deletion of its receptors. Mice with homozygous deletions in EP1 and EP4 receptors, but not EP3, were partially resistant to colon carcinogen mediated induction of aberrant crypt foci.54,55 EP2 disruption decreases the number and size of intestinal polyps in APCΔ716 knockout mice.56 Moreover, in carcinogen treated wild‐type mice, an EP1 receptor antagonist also decreased the incidence of aberrant crypt foci whereas ApcMin mice treated with the same EP1 receptor antagonist and an EP4 receptor antagonist developed 57% and 69% fewer intestinal polyps, respectively, than untreated mice.54,55 In addition to colorectal cancer, it has been shown that EP1, 2, and 4 receptors were elevated whereas EP3 receptor levels were decreased in mammary tumours in COX‐2‐MMTV mice.57 Furthermore, an EP1 receptor antagonist was shown to reduce tumour burden in a carcinogen induced rat mammary model.58 However, Amano and colleagues recently reported that EP3 receptor activation is required for lung tumour associated angiogenesis and tumour growth.59 In the future, it will be important to carefully determine the EP receptor profile in human cancers and to examine whether NSAIDs can modulate PGE2 receptor expression. Taken together, these findings may provide a rationale for the development of EP receptor antagonists which may offer an alternative to COX‐2 selective inhibitors.

PGE2 signalling pathways and its downstream targets

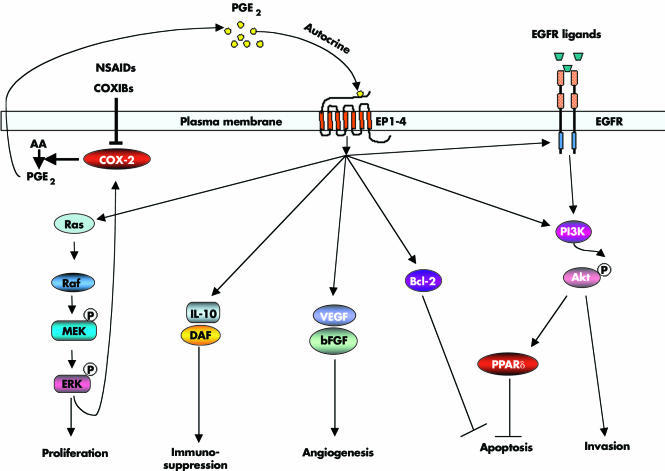

An increasingly large body of evidence indicates that PGE2 promotes tumour growth by stimulating EP receptor signalling with subsequent enhancement of cellular proliferation, promotion of angiogenesis, inhibition of apoptosis, stimulation of invasion/motility, and suppression of immune responses. These findings prompted research to elucidate PGE2 signalling pathways and identify PGE2 downstream targets that are involved in promoting tumour growth (fig 2).

Figure 2 Prostaglandin (PG) E2 in carcinogenesis. PGE2 promotes tumour growth by stimulating EP receptor downstream signalling and subsequent enhancement of cellular proliferation, promotion of angiogenesis, inhibition of apoptosis, stimulation of invasion/motility, and suppression of immune responses. NSAIDs, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs; COXIBs, COX‐2 selective inhibitors; AA, arachidonic acid; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; IL‐10, interleukin 10; DAF, decay accelerating factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; PPARδ, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor δ.

EGFR pathway

Both COX‐2 and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathways are activated in most human cancers.60 The observation that forced expression of COX‐2 in human colorectal cancer (CRC) cells stimulates cellular proliferation through induction of EGFR61 indicated the likelihood of crosstalk between these two pathways. We and others have demonstrated that PGE2 can transactivate EGFR, which results in stimulation of cell migration through increased PI3K‐Akt signalling in CRC cells.62,63,64 As expression of EGFR directly correlates with the ability of human CRC cells to metastasise to the liver,65 it is possible that inhibiting both the EGFR tyrosine kinase and COX‐2 at lower doses could yield additive effects, blocking the spread of metastatic disease. Moreover, preclinical studies support the notion that combined treatment of NSAIDs plus EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors is more effective than either single agent alone in several models. In colorectal carcinoma cells, blocking both COX‐2 and the HER‐2/neu pathways synergistically reduced tumour growth.66 In soft agar and xenograft assays, the combination of a COX‐2 selective inhibitor, an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and a protein kinase A antisense construct markedly reduced proliferation and angiogenesis of human colon and breast cancer cells.67 Similarly, combined treatment with inhibitors of both pathways significantly decreases polyp formation in ApcMin mice,68 as Apc deficiency is associated with increased EGFR activity in the intestinal enterocytes.69 Hence we feel that it will be essential to examine the use of COX‐2 selective inhibitors as potential agents in combination with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in clinical trials.

Nuclear receptor pathways

Peroxisome proliferator activated receptors δ(PPARδ, also referred to as PPARβ) is a ligand activated nuclear transcription factor that is a member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily. Published data indicate that the PPARδ/β is important for regulating fat metabolism,70 inhibiting obesity induced by either genetic or high‐fat‐diet,70 and decreasing weight gain and insulin resistance in mice fed high fat diets.71 However, PPARδ has been identified as a direct transcriptional target of the APC/β‐catenin/Tcf pathway.72 Our recent findings show that PGE2 transactivates PPARδ which in turn promotes tumour cell survival.33 PGE2 activates PPARδ via a PI3K‐Akt pathway. Most importantly, we demonstrated that PGE2 promotes intestinal epithelial cell survival and colorectal adenoma growth in Apcmin mice, but not in PPARδ‐/‐/Apcmin mice,33 indicating that PPARδ is a critical downstream mediator in PGE2 stimulated tumour growth. Consistent with this result, a selective PPARδ agonist also accelerates intestinal polyp growth in Apcmin mice via inhibition of tumour cell apoptosis.73 These results support the rationale for considering the development of PPARδ antagonists for use in cancer prevention and/or treatment and raise caution for developing PPARδ agonists for clinical use to treat dyslipidaemia, obesity, and insulin resistance.

Ras‐MAPK pathway

Ras is an oncogene and its activation is found in a wide variety of human malignancies. Ras induces cell transformation, proliferation, and survival by triggering downstream signalling pathways such as the Raf/MEK/ERKs and PI3K/Akt pathways. The Ras‐MAP kinase cascade is one of the major intracellular signalling pathways responsible for cell proliferation. Forced expression of constitutively active Ras (mutant Ras) or MEK upregulates COX‐2 expression and enhances cell proliferation in a variety of cell culture models, respectively.74,75,76,77 Non‐selective NSAIDs and COX‐2 selective inhibitors inhibit cell proliferation and transformation by blocking the Ras‐MAPK signalling pathway.78,79,80 Our group recently reported that PGE2 activates a Ras‐MAPK pathway which in turn upregulates COX‐2 expression and stimulates colorectal cancer cell proliferation.81 This finding supports a novel mechanism by which COX‐2 derived PGE2 promotes human cancer cell growth by autoregulation of COX‐2 expression, which depends primarily on PGE2 induced activation of the Ras‐MAPK pathway.

PGE2 downstream targets: angiogenic factors

Angiogenic factors are important for the growth and survival of endothelial cells and to stimulate vascular endothelial cell migration and capillary formation.82 Overexpression of COX‐2 in CRC cells induces the production of angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF),83 and NSAIDs block the production of these angiogenic factors leading to inhibition of proliferation, migration, and vascular tube formation.83,84,85,86 The observations that PGE2 can reverse the antiangiogenic activity of NSAIDs87 and homozygous deletion of EP2 completely abrogated induction of VEGF in APCΔ716 mouse polyps56 support the concept that PGE2 mediates the major role of COX‐2 in inducing expression of proangiogenic factors. Several reports demonstrated that PGE2 upregulates VEGF in cultured human fibroblasts88 and increases VEGF and bFGF expression through stimulation of ERK2/JNK1 signalling pathways in endothelial cells.89 EP2/EP4 mediate PGE2 induction of VEGF in ovarian cancer cells90 and human airway smooth muscle cells.91 Interestingly, VEGF and bFGF induce COX‐2 and subsequent PG production in endothelial cells, suggesting that the effects of PGE2 on regulation of VEGF and bFGF are likely amplified through a positive feedback loop.92 However, PGE2 induction of VEGF may provide another explanation for the undesired side effect of COX‐2 selective inhibitors on cardiovascular complications. VEGF is implicated in cardiovascular homeostasis. For example, treatment with Avastin (bevacizumab), a humanised anti‐VEGF antibody, has only marginal improvement in survival for colorectal cancer patients and is also associated with an increased risk of hypertension. Therefore, it is important to identify new molecular targets that drive colorectal tumour associated angiogenesis. Preliminary data from our laboratory indicate that PGE2 induces a proangiogenic chemokine expression in CRC cells (unpublished data).

PGE2 downstream targets: antiapoptotic factors

Overexpression of COX‐2 in rat intestinal epithelial cells increased their resistance to undergo apoptosis and resulted in increased Bcl‐2 protein expression.93 The role of COX‐2 in preventing apoptosis is likely mediated by COX‐2 derived PGE2, which attenuates cell death induced by the COX‐2 selective inhibitor SC‐58125.94 These findings have stimulated great interest in identifying PGE2 downstream targets responsible for modulating apoptosis. PGE2 induces antiapoptotic protein expression such as Bcl‐294 and increases NFκB transcriptional activity,95 which is a key antiapoptotic mediator. As chemotherapeutic agents and radiation therapy enhance COX‐2 protein expression as well as PGE2 synthesis in human cancer cells, elevated PGE2 production may increase resistance to therapy by giving cells a survival advantage. It will be important to determine whether patients treated with combinations of chemotherapy or/and radiation therapy with NSAIDs respond better than those not treated with NSAIDs. Preliminary study suggests that COX‐2 selective inhibitors may increase the beneficial effects of radiotherapy.96

PGE2 downstream targets: chemokines and their receptors

Although chemokines play a crucial role in immune and inflammatory reactions, recent studies indicate that they have an equally important role in the cancer.97 PGE2 has been shown to inhibit production of CC chemokines, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)‐1α and MIP‐1β, in dendritic cells via binding to the EP2 receptor,98,99 and suppress CC chemokine RANTES (regulated upon activation normal T cell expressed and secreted) production in human macrophages through the EP4 receptor.100 These CC chemokines are crucial for macrophage and lymphocyte infiltration in human breast, cervix, pancreas, and gliomas cancers.101,102 Moreover, a recent study showed that PGE2 mediates VEGF and bFGF induced CXCR4 dependent neovessel assembly in vivo.103 The important role of CXCR4 for cancer pharmacology is based on findings that activation of CXCR4 is involved in stimulating cancer cell migration and increasing invasion in breast, prostate, bladder, and pancreatic cancers.104,105,106,107 These preclinical data indicate that chemokines and their receptors are potential drug targets of PGE2 downstream signalling for cancer prevention and treatment.

PGE2 downstream targets: immunosuppressive mediators

The tumour microenvironment is predominantly shifted from a Th1 to a Th2 dominant response (immunosuppressive immune responses). COX‐2 selective inhibitors restore the tumour induced imbalance between Th1 and Th2 and promote antineoplastic responses in lung cancer108 and metastatic spread of colorectal cancer.109 These findings led to extensive efforts to understand how PGE2 can regulate immunosuppression. PGE2 has been shown to downregulate Th1 cytokines (tumour necrosis factor α, interferon γ, and interleukin (IL)‐2)110 and upregulate Th2 cytokines such as IL‐4, IL‐10, and IL‐6.111,112,113 IL‐10 is an immunosuppressive cytokine. Moreover, PGE2 can modulate immune function through inhibiting dendritic cell differentiation and T cell proliferation and suppressing the antitumour activity of natural killer cells and macrophages.114,115 In addition, our group showed that PGE2 upregulates the complement regulatory protein decay accelerating factor which results in blocking the complement C3 into two active compounds, C3a and C3b in CRC cells.116 Thus the effects of PGE2 on the immune system may allow neoplastic cells to evade attack.

Conclusions

Chemoprevention is being carefully evaluated on several fronts as an effective measure to insure cancer control. NSAIDs and COX‐2 selective inhibitors have been touted for their possible use as chemopreventive agents. However, concerns over the safety of COX‐2 selective inhibitors have prompted researchers to develop more effective chemopreventive agents with minimal toxicity. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of COX‐2 and its downstream targets will help to identify specific molecular targets for developing more safe agents which target this pathway. Preclinical studies provide evidence to demonstrate that non‐selective NSAIDs and COX‐2 selective inhibitors decrease the risk of colorectal cancer as well as other cancers through reduction of COX‐2 derived PGE2 synthesis. Significant progress has been made in the elucidation of PGE2 downstream signalling pathways which mediate the chemopreventive effect of NSAIDs. These cumulative data indicate that the development of agents that lower cellular levels of PGE2 or that specifically inhibit the PGE2 downstream signalling pathway might be useful for cancer prevention. PGE synthases, 15‐PDGH, and/or PGE2 receptors may also serve as rational targets for lowering cellular levels of PGE2 and EGFR, MAPK, and chemokines, and chemokine receptors are molecular targets for specific inhibition of PGE2 downstream signalling pathways. Moreover, another approach for decreasing the undesired side effects of COXIBs may be to lower the drug dose used. The combined use of multiple agents may allow for a lower dose of drug to be used. Taken together, efforts to develop novel chemopreventive agents with minimal toxicity and to design strategies for combinations of different agents targeting multiple pathways may yield significant benefits for cancer patients.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the United States Public Health Services Grants RO1‐DK‐62112 and PO1‐CA77839. RND is the Hortense B Ingram Professor of Molecular Oncology and the recipient of an NIH MERIT award (R37‐DK47297). We also thank the TJ Martell Foundation and the National Colorectal Cancer Research Alliance (NCCRA) for generous support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Smalley W, DuBois R N. Colorectal cancer and non steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs. Adv Pharmacol 1997391–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta R A, Dubois R N. Colorectal cancer prevention and treatment by inhibition of cyclooxygenase‐2. Nat Rev Cancer 2001111–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe M M, Lichtenstein D R, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med 19993401888–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vane J R, Bakhle Y S, Botting R M. Cyclooxygenases 1 and 2. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 19983897–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grover J K, Yadav S, Vats V.et al Cyclo‐oxygenase 2 inhibitors: emerging roles in the gut. Int J Colorectal Dis 200318279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vane J R. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a mechanism of action for aspirin‐like drugs. Nature 1971231232–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laine L, Harper S, Simon T.et al A randomized trial comparing the effect of rofecoxib, a cyclooxygenase 2‐specific inhibitor, with that of ibuprofen on the gastroduodenal mucosa of patients with osteoarthritis. Gastroenterology 1999117776–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A.et al Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group. N Engl J Med 20003431520–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman D G, Halaszynski T, Sinatra R.et al Rofecoxib does not compromise platelet aggregation during anesthesia and surgery. Can J Anaesth 2003501004–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson W F, Umar A, Viner J L.et al The role of cyclooxygenase inhibitors in cancer prevention. Curr Pharm Des 200281035–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thun M J, Henley S J, Patrono C. Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs as anticancer agents: mechanistic, pharmacologic, and clinical issues. J Natl Cancer Inst 200294252–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinbach G, Lynch P M, Phillips R K.et al The effect of celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor, in familial adenomatous polyposis. N Engl J Med 20003421946–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon S D, McMurray J J, Pfeffer M A.et al Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med 20053521071–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bresalier R S, Sandler R S, Quan H.et al Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med 20053521092–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nussmeier N A, Whelton A A, Brown M T.et al Complications of the COX‐2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 20053521081–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuper H, Adami H O, Trichopoulos D. Infections as a major preventable cause of human cancer. J Intern Med 2000248171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang D, Mann J R, DuBois R N. The role of prostaglandins and other eicosanoids in the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology 20051281445–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McAdam B F, Catella‐Lawson F, Mardini I A.et al Systemic biosynthesis of prostacyclin by cyclooxygenase (COX)‐2: the human pharmacology of a selective inhibitor of COX‐2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 199996272–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grosser T, Yusuff S, Cheskis E.et al Developmental expression of functional cyclooxygenases in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002998418–8423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cha Y I, Kim S H, Solnica‐Krezel L.et al Cyclooxygenase‐1 signaling is required for vascular tube formation during development. Dev Biol 2005282274–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DuBois R N, Abramson S B, Crofford L.et al Cyclooxygenase in biology and disease. FASEB J 1998121063–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rigas B, Goldman I S, Levine L. Altered eicosanoid levels in human colon cancer. J Lab Clin Med 1993122518–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uefuji K, Ichikura T, Mochizuki H. Cyclooxygenase‐2 expression is related to prostaglandin biosynthesis and angiogenesis in human gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res 20006135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rolland P H, Martin P M, Jacquemier J.et al Prostaglandin in human breast cancer: Evidence suggesting that an elevated prostaglandin production is a marker of high metastatic potential for neoplastic cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 1980641061–1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Needleman P, Isakson P C. The discovery and function of COX‐2. J Rheumatol 199724(suppl 49)6–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Portanova J P, Zhang Y, Anderson G D.et al Selective neutralization of prostaglandin E2 blocks inflammation, hyperalgesia, and interleukin 6 production in vivo. J Exp Med 1996184883–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson G D, Hauser S D, McGarity K L.et al Selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX)‐2 reverses inflammation and expression of COX‐2 and interleukin 6 in rat adjuvant arthritis. J Clin Invest 1996972672–2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amin A R, Attur M, Abramson S B. Nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenases: distribution, regulation, and intervention in arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 199911202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacDermott R P. Alterations in the mucosal immune system in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Med Clin North Am 1994781207–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gould S R, Brash A R, Conolly M E.et al Studies of prostaglandins and sulphasalazine in ulcerative colitis. Prostaglandins Med 19816165–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansen‐Petrik M B, McEntee M F, Jull B.et al Prostaglandin E(2) protects intestinal tumors from nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug‐induced regression in Apc(Min/+) mice. Cancer Res 200262403–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawamori T, Uchiya N, Sugimura T.et al Enhancement of colon carcinogenesis by prostaglandin E2 administration. Carcinogenesis 200324985–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang D, Wang H, Shi Q.et al Prostaglandin E(2) promotes colorectal adenoma growth via transactivation of the nuclear peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor delta. Cancer Cell 20046285–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mukherjee D, Nissen S E, Topol E J. Risk of cardiovascular events associated with selective COX‐2 inhibitors. JAMA 2001286954–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adderley S R, Fitzgerald D J. Oxidative damage of cardiomyocytes is limited by extracellular regulated kinases 1/2‐mediated induction of cyclooxygenase‐2. J Biol Chem 19992745038–5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kashfi K, Rigas B. Non‐COX‐2 targets and cancer: Expanding the molecular target repertoire of chemoprevention. Biochem Pharmacol 200570969–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shureiqi I, Chen D, Lee J J.et al 15‐LOX‐1: a novel molecular target of nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug‐induced apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000921136–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Z, DuBois R N. Par‐4, a proapoptotic gene, is regulated by NSAIDs in human colon carcinoma cells. Gastroenterology 20001181012–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, Yu J, Park B H.et al Role of BAX in the apoptotic response to anticancer agents. Science 2000290989–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto Y, Yin M J, Lin K M.et al Sulindac inhibits activation of the NF‐kappaB pathway. J Biol Chem 199927427307–27314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grilli M, Pizzi M, Memo M.et al Neuroprotection by aspirin and sodium salicylate through blockade of NF‐kappaB activation. Science 19962741383–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pradono P, Tazawa R, Maemondo M.et al Gene transfer of thromboxane A(2) synthase and prostaglandin I(2) synthase antithetically altered tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cancer Res 20026263–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beuckmann C T, Fujimori K, Urade Y.et al Identification of mu‐class glutathione transferases M2‐2 and M3‐3 as cytosolic prostaglandin E synthases in the human brain. Neurochem Res 200025733–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jakobsson P J, Thoren S, Morgenstern R.et al Identification of human prostaglandin E synthase: a microsomal, glutathione‐dependent, inducible enzyme, constituting a potential novel drug target. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999227220–7225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lazarus M, Munday C J, Eguchi N.et al Immunohistochemical localization of microsomal PGE synthase‐1 and cyclooxygenases in male mouse reproductive organs. Endocrinology 20021432410–2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tai H H, Ensor C M, Tong M.et al Prostaglandin catabolizing enzymes. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 200268–69483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coggins K G, Latour A, Nguyen M S.et al Metabolism of PGE2 by prostaglandin dehydrogenase is essential for remodeling the ductus arteriosus. Nat Med 2002891–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tong M, Tai H H. Synergistic induction of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide‐linked 15‐hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase by an androgen and interleukin‐6 or forskolin in human prostate cancer cells. Endocrinology 20041452141–2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Backlund M G, Mann J R, Holla V R.et al 15‐Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is down‐regulated in colorectal cancer. J Biol Chem 20052803217–3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan M, Rerko R M, Platzer P.et al 15‐Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase, a COX‐2 oncogene antagonist, is a TGF‐beta‐induced suppressor of human gastrointestinal cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 200410117468–17473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ding Y, Tong M, Liu S.et al NAD+‐linked 15‐hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15‐PGDH) behaves as a tumor suppressor in lung cancer. Carcinogenesis 20052665–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gee J R, Montoya R G, Khaled H M.et al Cytokeratin 20, AN43, PGDH, and COX‐2 expression in transitional and squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder. Urol Oncol 200321266–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quidville V, Segond N, Pidoux E.et al Tumor growth inhibition by indomethacin in a mouse model of human medullary thyroid cancer: implication of cyclooxygenases and 15‐hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase. Endocrinology 20041452561–2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watanabe K, Kawamori T, Nakatsugi S.et al Role of the prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP1 in colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 1999595093–5096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mutoh M, Watanabe K, Kitamura T.et al Involvement of prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP(4) in colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 20026228–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sonoshita M, Takaku K, Sasaki N.et al Acceleration of intestinal polyposis through prostaglandin receptor EP2 in ApcDelta716 knockout mice. Nat Med 200171048–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang S H, Liu C H, Conway R.et al Role of prostaglandin E2‐dependent angiogenic switch in cyclooxygenase 2‐induced breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004101591–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kawamori T, Uchiya N, Nakatsugi S.et al Chemopreventive effects of ONO‐8711, a selective prostaglandin E receptor EP(1) antagonist, on breast cancer development. Carcinogenesis 2001222001–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amano H, Hayashi I, Endo H.et al Host prostaglandin E(2)‐EP3 signaling regulates tumor‐associated angiogenesis and tumor growth. J Exp Med 2003197221–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kelloff G, Fay J, Steele V.et al Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors as potential cancer chemopreventives. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 19965657–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoshimoto T, Takahashi Y, Kinoshita T.et al Growth stimulation and epidermal growth factor receptor induction in cyclooxygenase‐overexpressing human colon carcinoma cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 2002507403–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sheng H, Shao J, Washington M K.et al Prostaglandin E2 increases growth and motility of colorectal carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 200127618075–18081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buchanan F G, Wang D, Bargiacchi F.et al Prostaglandin E2 regulates cell migration via the intracellular activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem 200327835451–35457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pai R, Soreghan B, Szabo I L.et al Prostaglandin E2 transactivates EGF receptor: A novel mechanism for promoting colon cancer growth and gastrointestinal hypertrophy. Nat Med 20028289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Radinsky R. Modulation of tumor cell gene expression and phenotype by the organ‐specific metastatic environment. Cancer Metastasis Rev 199514323–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mann M, Sheng H, Shao J.et al Targeting cyclooxygenase 2 and her‐2/neu pathways inhibits colorectal carcinoma growth. Gastroenterology 20011201713–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tortora G, Caputo R, Damiano V.et al Combination of a selective cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor ZD1839 and protein kinase A antisense causes cooperative antitumor and antiangiogenic effect. Clin Cancer Res 200391566–1572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Torrance C J, Jackson P E, Montgomery E.et al Combinatorial chemoprevention of intestinal neoplasia. Nat Med 200061024–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moran A E, Hunt D H, Javid S H.et al Apc deficiency is associated with increased Egfr activity in the intestinal enterocytes and adenomas of C57BL/6J‐Min/+ mice. J Biol Chem 200427943261–43272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang Y X, Lee C H, Tiep S.et al Peroxisome‐proliferator‐activated receptor delta activates fat metabolism to prevent obesity. Cell 2003113159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tanaka T, Yamamoto J, Iwasaki S.et al Activation of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor delta induces fatty acid beta‐oxidation in skeletal muscle and attenuates metabolic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 200310015924–15929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.He T C, Chan T A, Vogelstein B.et al PPARdelta is an APC‐regulated target of nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs. Cell 199999335–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gupta R A, Wang D, Katkuri S.et al Activation of nuclear hormone receptor peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐delta accelerates intestinal adenoma growth. Nat Med 200410245–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sheng G G, Shao J, Sheng H.et al A selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor suppresses the growth of H‐ras‐transformed rat intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 19971131883–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sheng H, Williams C S, Shao J.et al Induction of cyclooxygenase‐2 by activated Ha‐ras oncogene in Rat‐1 fibroblasts and the role of mitogen‐activated protein kinase pathway. J Biol Chem 199827322120–22127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Subbaramaiah K, Telang N, Ramonetti J T.et al Transcription of cyclooxygenase‐2 is enhanced in transformed mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res 1996564424–4429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Heasley L E, Thaler S, Nicks M.et al Induction of cytosolic phospholipase A2 by oncogenic Ras in human non‐small cell lung cancer. J Biol Chem 199727214501–14504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wong B C, Jiang X H, Lin M C.et al Cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor (SC‐236) suppresses activator protein‐1 through c‐Jun NH2‐terminal kinase. Gastroenterology 2004126136–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Husain S S, Szabo I L, Pai R.et al MAPK (ERK2) kinase—a key target for NSAIDs‐induced inhibition of gastric cancer cell proliferation and growth. Life Sci 2001693045–3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gala M, Sun R, Yang V W. Inhibition of cell transformation by sulindac sulfide is confined to specific oncogenic pathways. Cancer Lett 200217589–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang D, Buchanan F G, Wang H.et al Prostaglandin E2 enhances intestinal adenoma growth via activation of the Ras‐mitogen‐activated protein kinase cascade. Cancer Res 2005651822–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Iniguez M A, Rodriguez A, Volpert O V.et al Cyclooxygenase‐2: a therapeutic target in angiogenesis. Trends Mol Med 2003973–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tsujii M, Kawano S, Tsuji S.et al Cyclooxygenase regulates angiogenesis induced by colon cancer cells. Cell 199893705–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Masferrer J L, Leahy K M, Koki A T.et al Antiangiogenic and antitumor activities of cyclooxygenase‐2 Inhibitors. Cancer Res 2000601306–1311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Skopinska‐Rozewska E, Piazza G A, Sommer E.et al Inhibition of angiogenesis by sulindac and its sulfone metabolite (FGN‐1): a potential mechanism for their antineoplastic properties. Int J Tissue React 19982085–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sawaoka H, Tsuji S, Tsujii M.et al Cyclooxygenase inhibitors suppress angiogenesis and reduce tumor growth in vivo. Lab Invest 1999791469–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hernandez G L, Volpert O V, Iniguez M A.et al Selective inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor‐mediated angiogenesis by cyclosporin A: roles of the nuclear factor of activated T cells and cyclooxygenase 2. J Exp Med 2001193607–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Trompezinski S, Pernet I, Schmitt D.et al UV radiation and prostaglandin E2 up‐regulate vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in cultured human fibroblasts. Inflamm Res 200150422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pai R, Szabo I L, Soreghan B A.et al PGE(2) stimulates VEGF expression in endothelial cells via ERK2/JNK1 signaling pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001286923–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Spinella F, Rosano L, Di Castro V.et al Endothelin‐1‐induced prostaglandin E2‐EP2, EP4 signaling regulates vascular endothelial growth factor production and ovarian carcinoma cell invasion. J Biol Chem 200427946700–46705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bradbury D A, Clarke D L, Seedhouse C.et al Vascular endothelial growth factor induction by prostaglandin E2 in human airway smooth muscle cells is mediated by E prostanoid EP2/EP4 receptors and SP‐1 transcription factor binding sites. J Biol Chem 200528029993–30000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kage K, Fujita N, Oh‐hara T.et al Basic fibroblast growth factor induces cyclooxygenase‐2 expression in endothelial cells derived from bone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1999254259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tsujii M, DuBois R N. Alterations in cellular adhesion and apoptosis in epithelial cells overexpressing prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase‐2. Cell 199583493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sheng H, Shao J, Morrow J.et al Modulation of apoptosis by prostaglandin treatment in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res 199858362–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Poligone B, Baldwin A S. Positive and negative regulation of NF‐kappaB by COX‐2: roles of different prostaglandins. J Biol Chem 200127638658–38664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Davis T W, O'Neal J M, Pagel M D.et al Synergy between celecoxib and radiotherapy results from inhibition of cyclooxygenase‐2‐derived prostaglandin E2, a survival factor for tumor and associated vasculature. Cancer Res 200464279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer 20044540–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jing H, Vassiliou E, Ganea D. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits production of the inflammatory chemokines CCL3 and CCL4 in dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol 200374868–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jing H, Yen J H, Ganea D. A novel signaling pathway mediates the inhibition of CCL3/4 expression by PGE2. J Biol Chem 200427955176–55186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Takayama K, Garcia‐Cardena G, Sukhova G K.et al Prostaglandin E2 suppresses chemokine production in human macrophages through the EP4 receptor. J Biol Chem 200227744147–44154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 2001357539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bottazzi B, Polentarutti N, Acero R.et al Regulation of the macrophage content of neoplasms by chemoattractants. Science 1983220210–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Salcedo R, Zhang X, Young H A.et al Angiogenic effects of prostaglandin E2 are mediated by up‐regulation of CXCR4 on human microvascular endothelial cells. Blood 20031021966–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liang Z, Yoon Y, Votaw J.et al Silencing of CXCR4 blocks breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res 200565967–971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hart C A, Brown M, Bagley S.et al Invasive characteristics of human prostatic epithelial cells: understanding the metastatic process. Br J Cancer 200592503–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Eisenhardt A, Frey U, Tack M.et al Expression analysis and potential functional role of the CXCR4 chemokine receptor in bladder cancer. Eur Urol 200547111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Marchesi F, Monti P, Leone B E.et al Increased survival, proliferation, and migration in metastatic human pancreatic tumor cells expressing functional CXCR4. Cancer Res 2004648420–8427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Stolina M, Sharma S, Lin Y.et al Specific inhibition of cyclooxygenase 2 restores antitumor reactivity by altering the balance of IL‐10 and IL‐12 synthesis. J Immunol 2000164361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yao M, Kargman S, Lam E C.et al Inhibition of cyclooxygenase‐2 by rofecoxib attenuates the growth and metastatic potential of colorectal carcinoma in mice. Cancer Res 200363586–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Harris S G, Padilla J, Koumas L.et al Prostaglandins as modulators of immunity. Trends Immunol 200223144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Shreedhar V, Giese T, Sung V W.et al A cytokine cascade including prostaglandin E2, IL‐4, and IL‐10 is responsible for UV‐induced systemic immune suppression. J Immunol 19981603783–3789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Huang M, Stolina M, Sharma S.et al Non‐small cell lung cancer cyclooxygenase‐2‐dependent regulation of cytokine balance in lymphocytes and macrophages: up‐regulation of interleukin 10 and down‐regulation of interleukin 12 production. Cancer Res 1998581208–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Della Bella S, Molteni M, Compasso S.et al Differential effects of cyclo‐oxygenase pathway metabolites on cytokine production by T lymphocytes. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 199756177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yang L, Yamagata N, Yadav R.et al Cancer‐associated immunodeficiency and dendritic cell abnormalities mediated by the prostaglandin EP2 receptor. J Clin Invest 2003111727–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Goodwin J S, Ceuppens J. Regulation of the immune response by prostaglandins. J Clin Immunol 19833295–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Holla V R, Wang D, Brown J R.et al Prostaglandin E2 regulates the complement inhibitor CD55/decay‐accelerating factor in colorectal cancer. J Biol Chem 2005280476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]