Abstract

Cannabinoid receptors of type 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2), endogenous ligands that activate them (endocannabinoids), and mechanisms for endocannabinoid biosynthesis and inactivation have been identified in the gastrointestinal system. Activation of CB1 receptors by endocannabinoids produces relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter and inhibition of gastric acid secretion, intestinal motility, and fluid stimulated secretion. However, stimulation of cannabinoid receptors impacts on gastrointestinal functions in several other ways. Recent data indicate that the endocannabinoid system in the small intestine and colon becomes over stimulated during inflammation in both animal models and human inflammatory disorders. The pathological significance of this “endocannabinoid overactivity” and its possible exploitation for therapeutic purposes are discussed here.

Keywords: cannabinoid, inflammatory bowel disease, vanilloid, colitis, intestinal inflammation

The main psychotropic constituent of the plant Cannabis sativa and marijuana, Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabinol, exerts its pharmacological effects by activating two G protein coupled cannabinoid receptors.1 These are the CB1 receptor, present in central and peripheral nerves (including the human enteric nervous system), and the CB2 receptor, expressed abundantly in immune cells. In rodents, CB1 receptor immunoreactivity has been detected in discrete nuclei of the dorsovagal complex (involved in emesis), and in efferents from the vagal ganglia and in enteric (myenteric and submucosal) nerve terminals where they inhibit excitatory (mainly cholinergic) neurotransmission.2,3,4,5 In vivo pharmacological studies have shown that activation of CB1 receptors reduces emesis,6,7 produces inhibition of gastric acid secretion8 and relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter 9 (two effects that might be beneficial in the treatment of gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease), and inhibits intestinal motility and secretion.10,11 Consistent with immunohistochemical data showing that CB2 receptors are particularly evident in colonic tissues from patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD),12 evidence suggests that CB2 inhibits intestinal motility during certain pathological states.13

The endocannabinoid system of the gastrointestinal tract includes not only cannabinoid receptors but also endogenous agonists of these receptors (that is, the endocannabinoids anandamide and 2‐arachidonoylglycerol (2‐AG)), as well as mechanisms for their biosynthesis and inactivation. The latter occurs via cellular reuptake, which is facilitated by a putative membrane transporter, and enzymatic degradation by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) for both anandamide and 2‐AG, and by monoacylglycerol lipase for 2‐AG. The endocannabinoids have been detected in the digestive tract and there is evidence that at least anandamide is a physiological regulator of colonic propulsion in mice.10 This is consistent with data from phase III clinical trials that highlighted diarrhoea as one of the initial adverse events associated with administration of the antiobesity drug rimonabant, a selective CB1 receptor antagonist.14 Intestinal anandamide levels have been found to be increased after noxious stimuli, food deprivation, or clinically diagnosed colorectal cancer, thus suggesting a possible physiopathological role.11,15,16,17 In rodents, endocannabinoids convey protection from enteric hypersecretory states (for example, cholera toxin induced diarrhoea), which is in agreement with anecdotal reports from folk medicine on the use of Cannabis sativa in the treatment of diarrhoea.11

“The endocannabinoid system of the gastrointestinal tract includes not only cannabinoid receptors but also endogenous agonists of these receptors, as well as mechanisms for their biosynthesis and inactivation”

Endocannabinoids may also have targets other than cannabinoid receptors.18 The best characterised is the transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) receptor (the molecular target for the pungent component of hot chilli, capsaicin), which is mostly expressed by primary afferent neurones but also detected in myenteric and submucosal nerves.19 TRPV1 can be activated by anandamide, thus resulting in enteritis in the rat in vivo20 and enhanced acetylcholine release from myenteric guinea pig nerves.21 However, under physiological conditions, anandamide reduces mouse intestinal transit in vivo through activation of CB1, but not TRPV1, receptors.22

A high affinity binding site potentially involved in cellular reuptake of endocannabinoids has only recently been characterised in rat basophilic cells.23 There is no direct evidence for the existence of this putative protein in the gut as yet, although functional studies performed in mice using specific inhibitors of anandamide reuptake suggest that this process might be involved in the control of motility changes associated with experimental ileus16 and in the secretory diarrhoea evoked by cholera toxin.11 FAAH mRNA and activity have been detected in different regions of the rodent intestinal tract and functional studies performed using selective inhibitors suggest that this enzyme is physiologically involved in the control of intestinal motility.24,25

Endocannabinoid overactivity during intestinal inflammatory conditions

Evidence is accumulating to suggest that during inflammatory conditions affecting the intestine, as with other disorders,1,26 the tone of the endocannabinoid system is increased because of either increased expression of cannabinoid receptors or upregulation of endocannabinoid levels, or both. During croton oil induced inflammation and subsequent increase in upper gastrointestinal transit, expression of CB1 receptors in the mouse small intestine is enhanced and so is the inhibitory effect on motility observed following activation of these receptors.27 Also, the activity of the enzyme responsible for anandamide degradation, FAAH,28 was found to be increased, suggesting that enhanced turnover of anandamide occurs during croton oil induced inflammation. Massa and colleagues29 showed that CB1 receptor expression is increased in the colon of mice treated with intrarectal dinitrobenzene sulphonic acid (DNBS), an experimental model of colitis, and that genetic or pharmacological blockade of CB1 receptors causes worsening, whereas genetic ablation of FAAH causes amelioration, of the colon inflammatory score of these animals. More recently, D'Argenio and colleagues30 found that in the colon of DNBS treated mice and trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid treated rats, levels of anandamide, but not 2‐AG, were significantly increased. More importantly, further elevation of the amounts of this endocannabinoid, obtained by systemic administration of an inhibitor of anandamide cellular reuptake, was accompanied by complete reversal of histological and biochemical inflammatory parameters in the colon of DNBS treated mice.30 These findings, taken together, indicate that:

endocannabinoids and CB1 receptors are upregulated during intestinal inflammation;

enhanced endocannabinoid tone, by acting at least in part through CB1 receptors, affords protection against both epithelial damage and increased motility occurring during intestinal inflammation.

Depending on the type of inflammatory stimulus, CB1 receptors may not be the only molecular targets involved in the protective functions of endocannabinoids. Mathison and colleagues13 showed that the increase in gastrointestinal transit caused by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced inflammation in rats can be selectively counteracted by agonists of CB2, but not CB1, receptors. The effect was independent of nitric oxide but appeared to be mediated by cyclooxygenase derived products as it was attenuated by indomethacin. No experiment was performed by the authors to investigate whether CB2 agonists exert any direct anti‐inflammatory effect, as would be expected from the fact that activation of CB2 receptors causes inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines.31 Indeed, CB2 receptor agonists inhibit tumour necrosis factor α (TNF‐α) induced interleukin 8 release in human colonic epithelial cells, which are recognised to exert a major influence on maintenance of intestinal immune homeostasis.32 On the other hand, in a different study, the CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant was found to inhibit the LPS induced increase in plasma levels of TNF‐α in rats and wild‐type mice, but not in CB1 receptor null mice.33 This paradoxical effect of CB1 blockade might be due to the unmasking of CB2 mediated anti‐inflammatory effects exerted by enhanced endocannabinoid levels when CB1 receptors are blocked, although this possibility has not yet been investigated.

“Depending on the type of inflammatory stimulus, CB1 receptors may not be the only molecular targets involved in the protective functions of endocannabinoids”

More recently, the involvement in colon inflammation of another possible target of anandamide, the TRPV1 receptor, was also evaluated.34 Previous studies had shown that acute activation of this cation channel can contribute to intestinal inflammation,35,36,37 and that when TRPV1 agonists cause anti‐inflammatory effects they likely do so by causing desensitisation of these receptors.38 It was also shown that, following toxin A induced inflammation of the rat small intestine, anandamide levels are upregulated in this tissue and contribute towards worsening of the inflammatory score by activating TRPV1 receptors.20 Therefore, the finding of Massa et al that infusion of DNBS induced increased inflammation in TRPV1−/− mice compared with wild‐type littermates (TRPV1+/+) was quite unexpected. Electrophysiological recordings from circular smooth muscle cells, performed 8 and 24 hours after DNBS treatment, revealed strong spontaneous oscillatory action potentials in TRPV1−/− but not in TRPV1+/+ colons, indicating an early TRPV1 mediated control of inflammation induced irritation of smooth muscle activities rather than of epithelial cell damage. These results suggest that TRPV1 receptors, possibly by being activated by elevated anandamide levels observed in the colon following DNBS treatment,30 may also afford endogenous protection against colonic inflammation induced experimentally. Overall, these studies in experimental models of intestinal inflammation indicate that:

targets other than CB1 receptors (that is, TRPV1 and CB2 receptors) participate in endocannabinoid induced anti‐inflammatory effects in the gastrointestinal tract;

the same endocannabinoid target (for example, the TRPV1 receptor) may play protective or counterprotective roles in intestinal inflammation depending on the intestine section under study and the type of experimental animal model used (that is, chemically induced v bacteria induced inflammation, respectively).

“Overactivity of the endocannabinoid system is becoming a well established concept in human intestinal conditions with an inflammatory component”

Even with these sometimes discrepant results from animal studies, overactivity of the endocannabinoid system is also becoming a well established concept in human intestinal conditions with an inflammatory component. Significantly elevated CB2 receptor expression and anandamide levels were reported in colon biopsies from patients with ulcerative colitis,12,30 and elevated anandamide concentrations have been observed in intestinal samples from patients with diverticulosis,39 and in biopsies from patients with coeliac disease in the atrophic phase (Di Marzo V, Gianfrani C, Mazzarella G, and Sorrentini I, unpublished data). In the latter case, anandamide levels were found to return to normal following remission, thus suggesting that in humans, elevation of endocannabinoid (usually anandamide) intestinal levels represents an adaptive response aimed at providing protection from inflammation. How such protection is obtained and through which of the many endocannabinoid targets is still a matter of speculation. Importantly, activation of CB1 receptors might limit the effects of intestinal inflammation not only by regulating the activity of myenteric neurones27,34,39 but also by inducing wound closure in human colon epithelium in vitro, which is consistent with the presence of CB1 receptors in human colonic epithelial cells.12,17 Finally, human TRPV1 immunoreactivity is increased in the hypertrophic extrinsic nerve bundles in Hirschsprung's disease,40 which is important in the light of the observation that anandamide activates TRPV1 receptors more efficaciously when such receptors are overexpressed.18

Conclusions: new therapies for the treatment of IBD from the endocannabinoid system

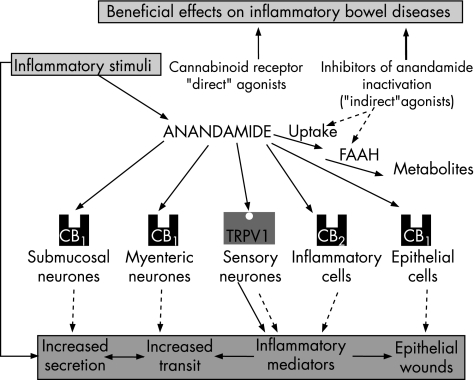

The inhibitory effects of cannabinoids on intestinal inflammation, as well as on intestinal motility and secretory diarrhoea, observed in preclinical studies, increase the potential for their use in the treatment of IBD. In fact, based on these data in animal studies, a clinical study with Cannabis in patients with relapse of chronic intermittent Crohn's disease has been started at the University Hospital of Munich.41 Particular attention will have to be paid during these studies to potential “central” side effects of Cannabis, such as tolerance and proconvulsant effects.42 Regarding the endocannabinoids, although the exact mechanisms of their anti‐inflammatory effects remain elusive, it is well established that they might be effective in relieving a number of symptoms experienced by patients with IBD, including nausea, anorexia, cramps, diarrhoea, pain, and inflammation. It appears that endocannabinoids might regulate the intestinal response to inflammation at three levels: (1) reducing the release of neurotransmitters that affect intestinal motility and secretion; (2) directly suppressing the production of proinflammatory mediators such as TNF‐α; and (3) promoting epithelial wound healing (fig 1). From our present knowledge, two possible strategies might be envisaged for the endocannabinoid based pharmacological inhibition of bowel inflammation without provoking psychotropic side effects such as those of marijuana, largely mediated by CB1 receptors in the brain:

Figure 1 Endocannabinoid control of intestinal inflammation. Inflammatory stimuli upregulate anandamide levels and, in some cases, its major molecular targets, the cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Depending on their cellular localisation, activation of these receptors by anandamide may cause various effects, in most cases leading to reduction of the consequences of inflammation. Therefore, blockers of anandamide inactivation (for example, inhibitors of anandamide cellular reuptake or intracellular hydrolysis by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH)), by elevating anandamide levels further, and thus “indirectly” activating anandamide targets only “where and when” there is enhanced anandamide turnover, might also produce therapeutic effects in intestinal inflammatory conditions, possibly more efficaciously and safely than “direct” cannabinoid receptor agonists. Anandamide may also activate vanilloid TRPV1 receptors (mostly located on primary afferent neurones), resulting in pro‐ (following activation) or anti‐ (after desensitisation) inflammatory effects. Continuous arrows denote stimulation, induction, or processing; broken arrows denote inhibition. TRPV1, transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 receptor

because activation of both CB1 and CB2 receptors is expected to elicit protective effects, the design of CB1/CB2 cannabinoid receptor agonists that do not cross the blood‐barrier may reduce intestinal inflammation and associated diarrhoea through activation of enteric cannabinoid receptors (see also Kimball and colleagues43 for a further example of the role played by both CB1 and CB2 receptors against chemically induced colitis and diarrhoea);

the use of inhibitors of endocannabinoid inactivation by increasing levels of anandamide only “where and when” this is upregulated (that is, in the intestine during inflammation), will have greater site and time selectivity than drugs directly acting on cannabinoid receptors “always and everywhere”.

“The inhibitory effects of cannabinoids on intestinal inflammation, as well as on intestinal motility and secretory diarrhoea, observed in preclinical studies, increase the potential for their use in the treatment of IBD”

This second approach would be preferable because it may lead to activation of all of the endocannabinoid targets involved in protection from inflammation, and is also expected to minimise some peripheral side effects (for example, tachycardia, hypotension) potentially associated with activation of cardiovascular CB1 receptors. Indeed, inhibitors of anandamide reuptake entirely abolish DNBS induced colon inflammation in mice without causing the undesirable behavioural side effects of psychoactive cannabinoids.30 As genetic inactivation of FAAH also affords protection in the same animal model of IBD,29 pharmacological targeting of this enzyme should also represent a therapeutic strategy. However, a FAAH inhibitor was found to be less efficacious than a reuptake inhibitor in this context, and to be ineffective at elevating anandamide levels.30 In fact, FAAH also catalyses the metabolism of other bioactive amides, including the anti‐inflammatory compound palmitoylethanolamide,44 which exerts inhibitory effects on intestinal motility45 and is elevated in patients with ulcerative colitis.44 It is thus possible that FAAH inhibition causes anti‐inflammatory actions by elevating levels of this and/or other bioactive FAAH substrates.

“There is great potential for the development of new therapeutic agents against intestinal inflammation from the endocannabinoid system”

In conclusion, there is great potential for the development of new therapeutic agents against intestinal inflammation from the endocannabinoid system. While full understanding of the mechanisms of the anti‐inflammatory actions of cannabinoid receptor activation is still to be pursued, ad hoc clinical studies will ascertain whether the promising results obtained in animals can be extrapolated to the clinic.

Acknowledgements

VDM would like to thank Epitech Srl. for partly supporting some of the studies reviewed in this article.

Abbreviations

2‐AG - 2‐arachidonoylglycerol

CB1 and CB2 - cannabinoid receptors of type 1 and 2

DNBS - dinitrobenzene sulphonic acid

FAAH - fatty acid amide hydrolase

IBD - inflammatory bowel diseases

LPS - lipopolysaccharide

TNF‐α - tumour necrosis factor α

TRPV1 - transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 channel

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Di Marzo V, Bifulco M, De Petrocellis L. The endocannabinoid system and its therapeutic exploitation. Nat Rev Drug Disc 20043771–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duncan M, Davison J S, Sharkey Ka. Endocannabinoids and their receptors in the enteric nervous system. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 200522667–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coutts A A, Izzo A A. The gastrointestinal pharmacology of cannabinoids. An update. Curr Opin Pharmacol 20044572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hornby P J, Prouty S M. Involvement of cannabinoid receptors in gut motility and visceral perception. Br J Pharmacol 20041411335–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massa F, Storr M, Lutz B. The endocannabinoid system in the physiology and pathophysiology of the gastrointestinal tract. J Mol Med 200583944–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darmani N A. Delta(9)‐tetrahydrocannabinol and synthetic cannabinoids prevent emesis produced by the cannabinoid CB(1) receptor antagonist/inverse agonist SR 141716A. Neuropsychopharmacology 200124198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Sickle M D, Oland L D, Ho W.et al Cannabinoids inhibit emesis through CB1 receptors in the brainstem of the ferret. Gastroenterology 2001121767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adami M, Frati P, Bestini S.et al Gastric antisecretory role and immunohistochemical localization of cannabinoid receptors in the rat stomach. Br J Pharmacol 20021351598–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehmann A, Blackshaw L A, Branden L.et al Cannabinoid receptor agonism inhibits transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations and reflux in dogs. Gastroenterology 20021231129–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinto L, Izzo A A, Cascio M G.et al Endocannabinoids as physiological regulators of colonic propulsion in mice. Gastroenterology 2002123227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Izzo A A, Capasso F, Costagliola A.et al An endogenous cannabinoid tone attenuates cholera toxin‐induced fluid accumulation in mice. Gastroenterology 2003125765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright K, Rooney N, Feeney M.et al Differential expression of cannabinoid receptors in the human colon: cannabinoids promote epithelial wound healing. Gastroenterology 2005129437–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathison R, Ho W, Pittman Q J.et al Effects of cannabinoid receptor‐2 activation on accelerated gastrointestinal transit in lipopolysaccharide‐treated rats. Br J Pharmacol 20041421247–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Gaal L F, Rissanen A M, Scheen A J.et al Effects of the cannabinoid‐1 receptor blocker rimonabant on weight reduction and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight patients: 1‐year experience from the RIO‐Europe study. Lancet 20053651389–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez R, Navarro M, Ferrer B.et al A peripheral mechanism for CB1 cannabinoid receptor‐dependent modulation of feeding. J Neurosci 2002229612–9617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mascolo N, Izzo A A, Ligresti A.et al The endocannabinoid system and the molecular basis of paralytic ileus in mice. FASEB J 2002161973–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ligresti A, Bisogno T, Matias I.et al Possible endocannabinoid control of colorectal cancer growth. Gastroenterology 2003125677–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Marzo V, De Petrocellis L. Non‐CB1, non‐CB2 receptors for endocannabinoids. In: Onaivi ES, Sugiura T, Di Marzo V, eds. Endocannabinoids. The brains's marijuana and beyond. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis‐CRC Press, 2006151–174.

- 19.Ward S M, Bayguinov J, Won K J.et al Distribution of the vanilloid receptor (VR1) in the gastrointestinal tract. J Comp Neurol 2003465121–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McVey D C, Schmid P C, Schmid H H.et al Endocannabinoids induce ileitis in rats via the capsaicin receptor (VR1). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003304713–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mang C F, Erbelding D, Kilbinger H. Differential effects of anandamide on acetylcholine release in the guinea‐pig ileum mediated via vanilloid and non‐CB1 cannabinoid receptor. Br J Pharmacol 2001134161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izzo A A, Capasso R, Pinto L.et al Effect of vanilloid drugs on gastrointestinal transit in mice. Br J Pharmacol 20011321411–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore S A, Nomikos G G, Dickason‐Chesterfield A K.et al Identification of a high‐affinity binding site involved in the transport of endocannabinoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 200510217852–17857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katayama K, Ueda N, Kurahashi Y.et al Distribution of anandamide amidohydrolase in rat tissues with special reference to small intestine. Biochim Biophys Acta 19971347212–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Capasso R, Matias I, Lutz B.et al Fatty acid amide hydrolase controls mouse intestinal motility in vivo. Gastroenterology 2005129941–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Marzo V, De Petrocellis L. Plant, synthetic, and endogenous cannabinoids in medicine. Annu Rev Med 200657553–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izzo A A, Fezza F, Capasso R.et al Cannabinoid CB1‐receptor mediated regulation of gastrointestinal motility in mice in a model of intestinal inflammation. Br J Pharmacol 2001134563–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cravatt B F, Giang D K, Mayfield S P.et al Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty‐acid amides. Nature 199638483–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massa F, Marsicano G, Hermann H.et al The endogenous cannabinoid system protects against colonic inflammation. J Clin Invest 20041131202–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D'Argenio G, Valenti M, Scaglione G.et al Up‐regulation of anandamide levels as an endogenous mechanism and a pharmacological strategy to limit colon inflammation. FASEB J 200620568–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein T W, Lane B, Newton C A.et al The cannabinoid system and cytokine network. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 20002251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ihenetu K, Molleman A, Parsons M E.et al Inhibition of interleukin‐8 release in the human colonic epithelial cell line HT‐29 by cannabinoids. Eur J Pharmacol 2003458207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Croci T, Landi M, Galzin A M.et al Role of cannabinoid CB1 receptors and tumor necrosis factor‐alpha in the gut and systemic anti‐inflammatory activity of SR 141716 (rimonabant) in rodents. Br J Pharmacol 2003140115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Massa F, Sibaev A, Marsicano G.et al Vanilloid receptor (TRPV1)‐deficient mice show increased susceptibility to dinitrobenzene sulfonic acid induced colitis. J Mol Med 200684142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kihara N, de la Fuente S G, Fujino K.et al Vanilloid receptor‐1 containing primary sensory neurones mediate dextran sulphate sodium induced colitis in rats. Gut 200352713–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geppetti P, Trevisani M. Activation and sensitisation of the vanilloid receptor: role in gastrointestinal inflammation and function. Br J Pharmacol 20041411313–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujino K, Takami Y, de la Fuente S G.et al Inhibition of the vanilloid receptor subtype‐1 attenuates TNBS‐colitis. J Gastrointest Surg 20048842–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goso C, Evangelista S, Tramontana M.et al Topical capsaicin administration protects against trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid‐induced colitis in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 1993249185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guagnini F, Valenti M, Mukenge S.et al Neural contractions in colonic strips from patients with diverticulosis: role of endocannabinoids and substance P. Gut 200655946–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Facer P, Knowles C H, Tam P K.et al Novel capsaicin (VR1) and purinergic (P2X3) receptors in Hirschsprung's intestine. J Pediatr Surg 2001361679–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Press release of the University Hospital of Munich, 3 February 2005 http://idw‐online.de/pages/de/news99374 (last accessed 14 July 2006)

- 42.Smith P F. Cannabinoids as potential anti‐epileptic drugs. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 20056680–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kimball E S, Schneider C R, Wallace N H.et al Agonists of cannabinoid receptor 1 and 2 inhibit experimental colitis induced by oil of mustard and by dextran sulfate sodium. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2006291G364–G371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Darmani N A, Izzo A A, Degenhardt B.et al Involvement of the cannabimimetic compound, N‐palmitoyl‐ethanolamine, in inflammatory and neuropathic conditions: Review of the available pre‐clinical data, and first human studies. Neuropharmacology 2005481154–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Capasso R, Izzo A A, Fezza F.et al Inhibitory effect of palmitoylethanolamide on gastrointestinal motility in mice. Br J Pharmacol 2001134945–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]