Abstract

Background

Clinical and experimental observations in animal models indicate that intestinal commensal bacteria are involved in the initiation and amplification of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). No paediatric reports are available on intestinal endogenous microflora in IBD.

Aims

To investigate and characterise the predominant composition of the mucosa‐associated intestinal microflora in colonoscopic biopsy specimens of paediatric patients with newly diagnosed IBD.

Methods

Mucosa‐associated bacteria were quantified and isolated from biopsy specimens of the ileum, caecum and rectum obtained at colonoscopy in 12 patients with Crohn's disease, 7 with ulcerative colitis, 6 with indeterminate colitis, 10 with lymphonodular hyperplasia of the distal ileum and in 7 controls. Isolation and characterisation were carried out by conventional culture techniques for aerobic and facultative‐anaerobic microorganisms, and molecular analysis (16S rRNA‐based amplification and real‐time polymerase chain reaction assays) for the detection of anaerobic bacterial groups or species.

Results

A higher number of mucosa‐associated aerobic and facultative‐anaerobic bacteria were found in biopsy specimens of children with IBD than in controls. An overall decrease in some bacterial species or groups belonging to the normal anaerobic intestinal flora was suggested by molecular approaches; in particular, occurrence of Bacteroides vulgatus was low in Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis and indeterminate colitis specimens.

Conclusion

This is the first paediatric report investigating the intestinal mucosa‐associated microflora in patients of the IBD spectrum. These results, although limited by the sample size, allow a better understanding of changes in mucosa‐associated bacterial flora in these patients, showing either a predominance of some potentially harmful bacterial groups or a decrease in beneficial bacterial species. These data underline the central role of mucosa‐adherent bacteria in IBD.

The gastrointestinal microbiota is usually described as a postnatally acquired organ, including a large variety of bacteria, the composition and activity of which can affect both systemic and intestinal physiology.1 Major functions of the intestinal microbiota include metabolic activities leading to saving of energy and absorbable nutrients, trophic effects on the intestinal epithelia, promotion of gut maturation and integrity, maintenance of intestinal immune homeostasis and defence against pathogenic bacteria.2 Modern microbiological analyses have documented that this complex microbial community varies in composition along the length of the gut (with an increased gradient from the stomach to the colon) and includes both rapidly transiting and relatively persisting organisms.1,2,3

The relationship between the immune system and the commensal flora is precarious, and its change may result in an inflammatory disease of the gut. In inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), an inappropriate response towards resident luminal bacteria induces devastating consequences if not promptly restrained.4,5 However, the pathogenesis of IBD is a complex interplay among different interacting elements, such as host susceptibility, which is partly genetically determined, mucosal immunity and the intestinal milieu.6 Experimental evidence indicates that the loss of tolerance to commensal bacteria can be underlined by different factors, such as defects in regulatory T cell function, excessive stimulation of mucosal dendritic cells and changes in the receptorial pattern.7,8,9 Recent studies on the critical constituents in the innate immune response, such as pattern recognition receptors (ie, toll‐like receptors and non‐obese diabetic isoforms) also suggest that indigenous commensal microflora may contribute to intestinal inflammation in genetically susceptible hosts.3,10,11

Indeed, to date, no specific bacterial agents have been identified as potential factors triggering intestinal inflammation, although the involvement of pathogenic bacteria cannot be excluded. Many studies have shown that bacterial flora differ between patients with IBD and healthy people.3,5,6,12,13 Patients with IBD have higher amounts of bacteria attached to their intestinal epithelial surface, even in the non‐inflamed mucosa, than healthy controls.12,14,15 Swidsinski et al12 have shown that bacteria are from diverse genera and some of them, especially Bacteroides spp, were identified in the epithelial layer, in some instances intracellularly. Indeed, the role of Bacteroides spp in IBD is still unclear: these anaerobic bacteria have been shown to exhibit proinflammatory properties in several IBD animal models, but a protective role and even a decrease in the relative proportion of the phylogenetic group13 have been postulated in other studies.16,17 Moreover, distinct adherent or invasive strains of Escherichia coli have been identified in the ileal mucosa of patients with Crohn's disease18 and the involvement of a new potentially pathogenic group of adherent invasive E coli has been suggested.19,20,21 Recently, a breakdown in the balance between putative species of “protective” versus “harmful” intestinal bacteria, a concept referred to as “dysbiosis”, has been postulated.22

However, although in the past decade data have been generated from in vitro studies, animal models and clinical trials on adult populations, the precise role of intestinal bacteria in IBD remains to be clarified. We investigated the predominant bacterial composition of the mucosa‐associated intestinal microflora in colonoscopic biopsy specimens from the ileum, caecum and rectum in paediatric patients with a recent diagnosis of IBD (Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis and indeterminate colitis) and in patients with lymphonodular hyperplasia (LNH) in the terminal ileum.23 A predominant or exclusive pattern of LNH in the distal ileum is not uncommonly diagnosed by paediatric gastroenterologists dealing with children investigated for symptoms and signs suggesting an IBD: whether it represents an early IBD is still disputed and is the object of studies.24 For our study, conventional bacterial isolation and culture techniques for aerobic and facultative‐anaerobic bacteria, 16S rRNA‐based amplification analysis for the detection of 14 anaerobic bacterial groups or species, and real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the quantitative determination of Bacteroides vulgatus have been used.

Patients and methods

Patients

In all, 42 patients (age range 2–16 years) referred to the Paediatric Gastroenterology Unit, University of Rome “La Sapienza”, Rome, Italy, for suspected IBD were studied: active Crohn's disease was diagnosed in 12, active ulcerative colitis in 7, indeterminate colitis in 6 and a diagnosis of LNH of the terminal ileum in 10. The LNH group presented with recurrent abdominal symptoms and signs, suggesting an inflammatory condition of the gut. Seven patients with functional intestinal disorder and with normal results on colonoscopy and histology served as controls. In the patient groups, there was no strong evidence of a difference in age or disease duration. The median (range) ages were 14.0 (12–17) years for the Crohn's disease group, 10.0 (8–13) years for the ulcerative colitis group, 10.6 (9–13) years for the indeterminate colitis group, 11.2 (8–14) years for the LNH group and 12.7 (9–16) years for the controls; median (range) disease duration were: 6 (2–12) weeks for the Crohn's disease group, 8 (3–12) weeks for the ulcerative colitis group, 7 (2–12) weeks for the indeterminate colitis group, 6 (3–10) weeks for the LNH group and 8 (4–16) weeks for the controls. All children with Crohn's disease showed an ileocolonic involvement, and all of them had a disease activity score in the moderate to severe range. All patients with ulcerative colitis had endoscopic evidence of pancolitis, also showing a “backwash ileitis”, and in all of them the disease was classified as severe. In patients with indeterminate colitis, the caecum and the right colon were the most commonly affected sites. The diagnostic investigation was carried out according to widely agreed international protocols. Infectious and systemic diseases as well as structural abnormalities of the gastrointestinal tract were excluded in all patients. No patient had food allergy or malabsorption, and invasive organisms, parasites and ova were not found in the stools. Clostridium difficile or its toxins were not detected in the stool of patients included in the study. Children who had received antibiotics within 3 months as well as those who had received any corticosteroid within 4 weeks before the study were excluded. No patients had previous treatment with azathioprine/6‐mercaptopurine, ciclosporin or other immunosuppressive agents at any time before the enrolment. Patients who had received sulfasalazine or mesalazine were eligible if the drugs had been taken within a stable regimen for >4 weeks before the beginning of the study. Patients who had received a colonic cleaning procedure at least 3 months before the study were not eligible. All patients underwent ileocolonoscopy after parental informed written consent. In all patients, the colonic cleaning procedure was carried out using the same oral polyethylene glycol solution. The solution was given through a nasogastric tube if patients were poorly compliant. Endoscopy was performed in all patients by the same endoscopist with a paediatric videocolonoscope (Pentax 3440FK, Hamburg, Germany) after conscious sedation with intravenous pethidine (1–2 mg/kg) and midazolam (0.1 mg/kg). Mucosa of the distal ileum and caecum was inspected for the presence of changes, such as lymphoid nodular hyperplasia, disappearance of vascular pattern, areas of erythema and oedema, erosions, ulcerations (small, large or serpiginous), cobblestoning and inflammatory polyps. Mucosal biopsy specimens were taken during endoscopy only from the macroscopically involved sites and examined for the presence of inflammatory features, such as increased cellularity of the lamina propria, basal lymphoid aggregates, crypt distortion or atrophy, cryptitis or crypt abscesses, goblet‐cell depletion, epithelial abnormalities and granuloma in the lamina propria.

Ulcerative colitis was diagnosed when at least three of the following findings were present:

history of diarrhoea, or blood or mucus in the stools;

evidence of continuous macroscopic inflammation extending from the rectum to the proximal regions of the caecum;

histological features typical of ulcerative colitis;

exclusion of Crohn's disease of the small bowel through radiology, endoscopy and histology.

Crohn's disease was diagnosed when at least three of the following findings were present:

typical clinical features, such as weight loss, abdominal pain and diarrhoea;

typical features of macroscopic inflammation, such as discontinuous and patchy lesions, segmental inflammation, aphtoid ulcers, serpiginous or large ulcerations, cobblestoning or strictures;

evidence of strictures on x rays at the level of the small bowel, evidence of segmental colitis or fistulae;

histological evidence of deep focal or diffuse inflammatory infiltrate towards the lamina propria or epithelioid granuloma with giant cells.

Indeterminate colitis was diagnosed if there were no definite criteria for the diagnosis of Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis despite clear macroscopic or microscopic evidence of IBD.25 LNH was diagnosed by endoscopy if clusters of lymphoid nodules were observed in the terminal ileum and in colonic areas after filling the area to be inspected with air.

Treatment of biopsy specimens

Biopsy specimens, taken from the ileum, caecum and rectum of the patients, were analysed for pathological evaluation of the inspected mucosa as well as for bacteriological study. For the bacteriological study, specimens were immediately processed in the Microbiology Laboratory, Public Health Department, University of Rome “La Sapienza”, Rome, Italy. Biopsy washing was carried out according to Swidsinski et al.12 Briefly, two biopsy samples (15 mg of each) were first washed in 500 μl of physiological saline with 0.016% dithioerythritol to remove the mucus and then washed three times in 500 μl of physiological saline by shaking for 30 s each time. After the fourth wash, the biopsy specimens were hypotonically lysed by vortexing for 30 min in 500 μl distilled water to analyse mucosal aerobic and facultative‐anaerobic bacteria, or were processed for DNA extraction for the molecular detection of anaerobic bacteria.

Culture conditions for aerobic and facultative‐anaerobic bacteria

The cell debris left after hypotonic lysis (100 μl) was plated in tenfold dilution steps onto elective and differential media (Oxoid, Wiesel, Germany). For the isolation, Columbia blood agar for total microorganisms, selective Columbia blood agar with colistin‐nalidix acid supplement for Gram‐positive microorganisms, MacConkey agar without supplements for Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococcus‐selective bile–aesculin azide agar for Enterococcus spp, Schiemann Cefsulodin, Irgasan, Novobiocin medium for Yersinia spp, Skirrow selective medium for Campylobacter spp, Oxford agar for Listeria spp and Sabouraud medium for yeasts were used. Single colonies were chosen for further investigations. Biochemical identification was determined by api 32 ID, api NE, api Strep, api Staph (bio‐Mérieux‐Italia, Rome, Italy) according to the manufacturer's procedure.

Bacterial strains

The strains listed below were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and used to evaluate the specificity of the PCR primer set: Bifidobacterium adolescentis ATTC 15703, Bifidobacterium longum ATTC 15707, Eubacterium biforme ATTC 27806, Fusobacterium prausnitzii ATTC 27766, Peptostreptococcus productus, ATTC 27340, Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 11975, Bacteroides fragilis ATTC 23745, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron ATTC 29148, Bacteroides vulgatus ATTC 8482, Bacteroides distasonis ATTC 8503, Clostridium clostridiiforme ATCC 25537. Lactobacillus acidophilus was grown in lactobacilli de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe broth (Oxoid); all other microorganisms were cultured on anaerobe basal plates or broth (Oxoid) and incubated in an anaerobic chamber (in an atmosphere of 80% nitrogen, 10% carbon dioxide and 10% hydrogen) at 37°C.

DNA extraction

After the fourth washing, the biopsy specimens were incubated with 180 μl ATL buffer and 20 μl proteinase K (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA) at 55°C for 2 h and then with 20 μl lysozyme for a further 2 h at 37°C. DNA was extracted with the DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA concentration was determined using an Eppendorf biophotometer at 260 nm. In the amplification assays, 50 ng of DNA were used.

PCR amplification assays

The suitability of DNA for analysis was checked by amplification of the β‐globin gene sequence. Aliquots of each DNA sample (50 ng) were amplified with specific primers: forward primer, 5′‐CAACTTCATCCACGTTCACC‐3; reverse primer, 5′‐GAAGAGCCAAGGACAGGTAC‐3′. Amplification reactions were carried out in a 50‐μl volume containing 1× PCR buffer II (Applied Biosystems, Roche, California, USA), 3 mM magnesium chloride, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 50 pmol each primer and 5 Uμ/l AmpliTaq Gold polymerase (Applied Biosystems). The PCR was carried out under the following conditions: 1 cycle of 95°C for 7 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min and 1 cycle of 72°C for 7 min.

The 16S rRNA‐gene‐targeted primers used for the detection of anaerobic bacterial species or groups were synthesised by M‐Medical Genenco, according to the sequences already published by Wang et al26 and Matsuki et al27 (table 1). Amplification reactions were carried out in a 50‐μl volume containing 1×PCR buffer II, 50 pmol of each primer and 5 U/μl of AmpliTaq Gold polymerase. The amplification programme for Prevotella spp, Bifidobacterium spp (that includes B adolescentis, B breve, B catenulatum and B longum), Clostridium coccoides group (that includes C clostridiiforme, Ruminococcus gnavus and C coccoides) and Bacteroides fragilis group (that includes B caccae, B fragilis, B ovatus and Bthetaiotaomicron) was 1 cycle of 95°C for 7 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 55°C or 50°C for 20 s, 72°C for 30 s and 1 cycle of 72° for 5 min. The PCR for Clostridium clostridiiforme, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Bacteroides distasonis, Bacteroides vulgatus, Bifidobacterium adolescentis, Bifidobacterium longum, Eubacterium biforme, Fusobacterium prausnitzii, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Peptostreptococcus productus was carried out under the following conditions: 1 cycle of 95°C for 7 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 3 s, 55°C or 50°C for 10 s, and 74°C for 35 s, 1 cycle of 74°C for 2 min and 45°C for 2 s. The amplification products were subjected to gel electrophoresis in 2% agarose.

Table 1 Polymerase chain reaction primers used.

| Target bacteria | Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) | Product size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevotella | g‐Prevo‐F | CACRGTAAACGATGGATGCC | 527–529 | Matsuki et al27 |

| g‐Prevo‐R | GGTCGGGTTGCAGACC | |||

| Bifidobacterium spp | g‐Bifid‐F | CTCCTGGAAACGGGTGG | 549–563 | Matsuki et al27 |

| g‐Bifid‐R | GGTGTTCTTCCCGATATCTACA | |||

| Clostridium coccoides group | g‐Ccoc‐F | AAATGACGGTACCTGACTAA | 438–441 | Matsuki et al27 |

| g‐Ccoc‐R | CTTTGAGTTTCATTCTTGCGAA | |||

| Clostridium clostridiiforme | CC‐1 | CCGCATGGCAGTGTGTGAAA | 255 | Wang et al26 |

| CC‐2 | CTGCTGATAGAGCTTTACATA | |||

| Bacteroides fragilis group | g‐BfraF | ATAGCCTTTCGAAAGRAAGAT | 501 | Matsuki et al27 |

| g‐BfraR | CCAGTATCAACTGCAATTTTA | |||

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | BT‐1 | GGCAGCATTTCAGTTTGCTTG | 423 | Wang et al26 |

| BT‐2 | GGTACATACAAAATTCCACACGT | |||

| Bacteroides vulgatus | BV‐1 | GCATCATGAGTCCGCATGTTC | 287 | Wang et al26 |

| BV‐2 | TCCATACCCGACTTTATTCCTT | |||

| Bacteroides distasonis | BD‐1 | GTCGGACTAATACCGCATGAA | 273 | Wang et al26 |

| BD‐2 | TTACGATCCATAGAACCTTCAT | |||

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis | BIA‐1 | GGAAAGATTCTATCGGTATGG | 244 | Wang et al26 |

| BIA‐2 | CTCCCAGTCAAAAGCGGTT | |||

| Bifidobacterium longum | BIL‐1 | GTTCCCGACGGTCGTAGAG | 153 | Wang et al26 |

| BIL‐2 | GTGAGTTCCCGGCATAATCC | |||

| Eubacterium biforme | EBI‐1 | GCTAAGGCCATGAACATGGA | 46 | Wang et al26 |

| EBI‐2 | GCCGTCCTCTTCTGTTCTC | |||

| Fusobacterium prausnitzii | FPR‐1 | AGATGGCCTCGCGTCCGA | 199 | Wang et al26 |

| FPR‐2 | CCGAAGACCTTCTTCCTCC | |||

| Peptostreptococcus productus | PSP‐1 | AACTCCGGTGGTATCAGATG | 268 | Wang et al26 |

| PSP‐2 | GGGGCTTCTGAGTCAGGTA | |||

| Lactobacillus acidophilus | LAA‐1 | CATCCAGTGCAAACCTAAGAG | 286 | Wang et al26 |

| LAA‐2 | GATCCGCTTGCCTTCGCA | |||

Real‐time PCR assays

The primers and probes for Bacteroides vulgatus were based on 16S rRNA gene sequences available from GenBank. The GenBank programme BLAST was used to ensure that the proposed primers were complementary with the target species but not with other species. The primers and probe were selected from these specific sequences with Primer Express software V.2.0, provided with the ABI Prism 7300 sequence detector, and were obtained from Applied Biosystems. For Bacteroides vulgatus, the forward primer sequence was 5′‐CAGTTGAGGCAGGCGGAAT‐3′, the reverse primer sequence was 5′‐CCTTCGCAATCGGAGTTCTT‐3′ and the sequence of the probe was 5′‐CGTGGTGTAGCGGTGAAATGCTTAGATATCA‐3′. The fluorescent reporter dye at the 5′ end of the probe was 6‐carboxyfluorescein; the quencher at the 3′ end was 6‐carboxy‐N, N, N, N‐tetramethylrhodamine. The real‐time PCR amplifications were carried out in 25 μl reaction volumes containing 2× TaqMan Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), each primer at a concentration of 300 nM, fluorescent‐labelled probe at a concentration of 200 nM, and 4 μl (50 ng) of DNA extracted from biopsy specimens. All reactions were performed in duplicate, and for amplification and detection, an ABI PRISM 7300 sequence detection system was used. The amplification parameters used were as follows: 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles, each of which comprised 95°C for 15 s and 55°C for 1 min. Each run contained both negative and positive controls. Real‐time data were analysed with Sequence Detection Systems software (Becton‐Dickinson).

A reference curve for Bacteroides vulgatus ATCC 8482 was generated as follows: the bacteria were grown anaerobically in 10 ml of anaerobe basal broth (Oxoid) at 37°C for 24 h. These cultures were diluted with physiological saline until they reached a McFarland 0.5 standard, representing 108 microorganisms/ml, as determined by plating 100 μl of tenfold serial dilutions of these cultures onto anaerobe basal agar plates (Oxoid); these dilutions were used for DNA extraction with UltraClean (MO BIO Laboratories, Solana Beach, California, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Starting from a DNA concentration of 50 ng, tenfold dilutions were prepared to obtain different cell concentrations (concentration range 0.005–50 000 pg). The assay was run twice for each dilution, with Ct values ranging between 12.8 and 33.6. Equivalent copy number and Ct were automatically generated by the instrument for two replicate sets of controls. The reference curve was used to extrapolate the equivalent number of colony‐forming units (cfu) of Bacteroidesvulgatus in the biopsy specimens.

Statistical analysis

All significance tests carried out were non‐parametric. For comparisons between two groups the Mann–Whitney U test was used and to compare more than two groups the Kruskall–Wallace method, analogous to one‐way analysis of variance, was used. The levels of significance reported are not adjusted to take account of multiple comparisons. As these are multiple comparisons, p values <1% were considered significant to imply strong evidence of a difference.

Results

Mucosa‐associated aerobic and facultative‐anaerobic bacterial concentrations in different gut locations

The concentration of mucosa‐associated bacteria after the fourth wash and hypotonic lysis from ileum, caecum and rectum biopsy specimens of paediatric patients with IBD and LNH was compared with that of controls (table 2). As shown in table 2, in the ileum, total aerobe and facultative‐anaerobe counts, as well as total Gram‐negative bacterial counts, were significantly higher in patients with Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis and indeterminate colitis than in controls. Although an increased number of Gram‐positive bacteria were also detected in mucosal biopsy specimens of patients with IBD, the difference was not significantly different from controls. In the ileal mucosa of the patients with LNH, the whole bacterial concentration and that of Gram‐negative and Gram‐positive bacteria were increased. In table 2, in both LNH and the other IBD subgroups, a generalised increase in total mucosa‐associated bacteria was observed in the other locations analysed in the gut (caecum and rectum). The trend of bacterial concentration in the different gut locations showed a higher number of bacterial counts in the ileum and rectum, coupled with a lower colonisation in the caecum, whereas in controls the bacterial colonisation was lower in all the segments examined.

Table 2 Median concentrations (range; ×103 cfu/ml) of aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria detected after lysis of biopsy specimens.

| Controls, n = 7 | CD, n = 12 | UC, n = 7 | IC, n = 6 | LNH, n = 10 | K–W* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ileum | ||||||

| Total aerobes and facultative anaerobes | 0 (0–2.4) | 147 (3.31–1100) | 150 (11.6–400) | 201 (40.6–780) | 7.9 (0.007–480) | p = 0.001 |

| p = 0.005 | p = 0.005 | p = 0.005 | p = 0.01 | |||

| Total Gram‐negative bacteria† | 0 (0–0.26) | 147 (0.8–830) | 150 (10.6–350) | 120 (0–400) | 9.8 (0–480) | p = 0.046 |

| p = 0.005 | p = 0.005 | p = 0.01 | p = 0.01 | |||

| Total Gram‐positive bacteria‡ | 0 (0–2.35) | 0.77 (0–55) | 7.2 (0–150) | 50.9 (0.4–580) | 0.35 (0–20) | p = 0.039 |

| p = 0.18 | p = 0.05 | p = 0.01 | p = 0.49 |

| Controls, n = 4 | CD, n = 11 | UC, n = 6 | IC, n = 4 | LNH, n = 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caecum | ||||||

| Total aerobes and facultative anaerobes | 0.88 (0–50) | 54 (2.09–660.49) | 64 (10.59–360.36) | 350 (10.15–518) | 16 (0.16–100) | p = 0.056 |

| p = 0.02 | p = 0.07 | p = 0.06 | p = 0.29 | |||

| Total Gram‐negative bacteria† | 0.08 (0–50) | 53 (0.26–660) | 57 (1–360) | 64 (10–300) | 0.16 (0–100) | p = 0.074 |

| p = 0.02 | p = 0.07 | p = 0.11 | p = 0.73 | |||

| Total Gram‐positive bacteria‡ | 0 (0–1.6) | 0.5 (0–83) | 2.33 (0.16–80.6) | 150 (0.15–490) | 0.3 (0–100) | p = 0.347 |

| p = 0.17 | p = 0.07 | p = 0.06 | p = 0.4 |

| Controls, n = 4 | CD, n = 8 | UC, n = 6 | IC, n = 4 | LNH, n = 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rectum | ||||||

| Total aerobes and facultative anaerobes | 4.21 (0.97–50) | 186.05 (100–739) | 28.3 (10.76–138.7) | 460 (268.6–1200) | 60 (0.92–510) | p = 0.006 |

| p<0.005 | p = 0.11 | p = 0.03 | p = 0.29 | |||

| Total Gram‐negative bacteria† | 1.4 (0–30) | 164.5 (60–650) | 28 (10.6–109) | 115.5 (20–400) | 2.4 (0–500) | p = 0.20 |

| p = 0.00 | p = 0.07 | p = 0.11 | p = 0.90 | |||

| Total Gram‐positive bacteria‡ | 2.81 (0.97–20) | 44.55 (0–90) | 0.3 (0–473) | 312.8 (120–1000) | 2.32 (0–100) | p = 0.001 |

| p = 0.21 | p = 0.48 | p = 0.03 | p = 0.90 |

CD, Crohn's disease; cfu, colony forming units; IC, indeterminate colitis; K–W, Kruskal–Wallis; LNH, lymphonodular hyperplasia, UC, ulcerative colitis.

*p Values obtained from the Kruskal–Wallis test for the five groups.

†Data refer to Enterobacteriaceae, which were the predominant bacteria found.

‡Data refer to Staphylococcus and Streptococcus spp, which were the predominant bacteria found.

Bold values as compared with controls using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Owing to the multiple comparisons, only p⩽0.01 should be interpreted as strong evidence of a difference.

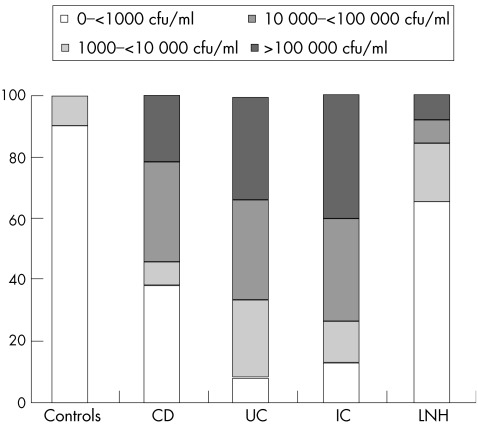

Figure 1 shows the percentage of patients with different concentration ranges of ileal mucosal bacteria (undetectable–<1000, 1000–<10 000, 10 000–<100 000 and >100 000 cfu/ml). Up to 90% of controls and 65% of patients with LNH showed concentrations of bacteria <1000 cfu/ml, whereas higher bacterial concentrations were prevalent in biopsy specimens of patients with IBD, reaching values >100 000 cfu/ml in 22%, 33% and 40% of patients with Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis and indeterminate colitis, respectively.

Figure 1 Percentage of patients with different concentrations of total aerobic and facultative‐anaerobic mucosal bacteria. CD, Crohn's disease; cfu, colony forming units; IC, indeterminate colitis; LNH, lymphonodular hyperplasia, UC, ulcerative colitis.

Distribution of bacterial isolates from aerobic and facultative‐anaerobic culture of ileum mucosa

Identification of the bacteria from ileal mucosa in all patient groups showed that 54 of 104 (52%) cultured isolates were Gram negative, whereas the remaining were Gram positive. Among Gram‐negative organisms, only bacteria belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family were found: 38 of 54 (74%) were identified as E coli, 13 (24%) as Klebsiella spp and 3 (6%) as Proteus spp, whereas in control samples E coli was the only Gram‐negative species found. All of these species were represented in mucosal samples of patients with Crohn's disease and in an average of almost two in the other pathological samples examined. The Gram‐positive population was represented by Streptococcus spp, Enterococcus spp and Staphylococcus spp, accounting for 18 (36%), 27 (54%) and 10 (20%) of 50 Gram‐positive isolates, respectively.

Table 3 gives the occurrence of aerobic and facultative‐anaerobic Gram‐negative and Gram‐positive species in ileal mucosa biopsy specimens, reported as number and percentage of isolates found in relation to the total Gram‐negative or Gram‐positive isolates detected in each patient group. Data analysis showed a generalised similar distribution of bacterial species isolated among all patient groups, with the species most markedly represented in specimens from ileum belonging to Escherichia and Enterococcus genera. Listeria, Yersinia, Campylobacter and yeasts were never cultured.

Table 3 Distribution of bacterial isolates from aerobic and facultative‐anaerobic culture of ileal mucosal samples.

| Total Gram negative | Total Gram positive | E coli | Klebsiella spp | Proteus spp | Streptococcus spp | Enterococcus spp | Staphylococcus spp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n % | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Controls | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70.0) | 3 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (28.5) | 4 (57.0) | 1 (14.2) |

| CD | 18 (51.4) | 12 (48.6) | 12 (66.7) | 3 (16.7) | 3 (16.7) | 5 (29.4) | 8 (47.1) | 4 (23.5) |

| UC | 12 (50.0) | 12 (50.0) | 10 (83.3) | 2 (16.6) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| IC | 7 (46.6) | 8 (53.3) | 3 (42.8) | 4 (57.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (25.0) | 4 (50.0) | 2 (25.5) |

| LNH | 14 (44.0) | 11 (56.0) | 20 (71.4) | 4 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (45.4) | 3 (27.3) | 3 (27.3) |

CD, Crohn's disease; IC, indeterminate colitis; LNH, lymphonodular hyperplasia; n, number of bacterial isolates; UC, ulcerative colitis; %, percentage of strains isolated in ileum mucosa biopsy specimens calculated as number of isolates found with respect to total Gram‐negative or Gram‐positive isolates detected in each group.

When the occurrence of bacterial species in each patient group was analysed, E coli was detected in 9 of the 12 (75%) patients with Crohn's disease, in all (100%) patients with ulcerative colitis, in 3 of the 6 (50%) patients with indeterminate colitis, in 8 of the 11 (72%) patients with LNH and in 2 of the 8 (25%) controls. Enterococcus spp was detected in 6 of the 12 (50%) patients with Crohn's disease, in 5 of the 7 (71%) patients with ulcerative colitis, in 4 of the 6 (67%) patients with indeterminate colitis, in 3 of the 11 (23%) patients with LNH and in 3 of the 8 (37%) controls. Klebsiella spp were found only in biopsy specimens from patients with IBD and, in particular, its detection was markedly increased in patients with indeterminate colitis (83%).

A similar trend was found for the occurrence of Gram‐negative and Gram‐positive species from cultures of biopsy specimens derived from the caecum and rectum (data not shown).

Percentage of patients with positive PCR for anaerobic bacterial groups or species

The biodiversity of mucosa‐associated anaerobic flora from ileum, caecum and rectum specimens was assessed by PCR. The choice of the anaerobic bacterial groups and species was based on previous reports that treated the relative frequency of bacterial species found in the human intestinal tract28 associated with the mucosa of healthy people and patients with IBD,29 and detectable in the normal faecal flora.30 Table 4 shows that, given the small sample sizes, in patients with IBD and LNH, the occurrence of Bifidobacterium spp, B adolescentis, B longum, E biforme, F prausnitzii, P productus, L acidophilus, Bacteroides fragilis group, B distasonis, Clostridium coccoides group and C clostridiiforme do not differ markedly compared with controls. Conversely, the detection rate of B thetaiotaomicron seems to be lower in ileal mucosa of patients with Crohn's disease and was undetectable in the caecum and rectum mucosa of patients with indeterminate colitis. However, the pattern of incidence of B vulgatus seems to be the most different, the occurrence of PCR positivity for this anaerobe being lower in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, as compared with controls, whereas all patients with indeterminate colitis were negative. The occurrence of both of these Bacteroides spp was almost never associated in each patient group studied. The detection rate of Prevotella spp in rectal biopsy specimens from patients with ulcerative colitis was higher than in controls.

Table 4 Number of patients with positive polymerase chain reaction for anaerobic bacterial groups or species in biopsies from ileum, caecum and rectum.

| Controls | CD | UC | IC | LNH | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | C | R | I | C | R | I | C | R | I | C | R | I | C | R | |

| Total patients (n) | 8 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 12 | 5 | 5 |

| Bifidobacterium spp | 8 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 2 |

| B adolescentis | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B longum | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Prevotella spp | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Clostridium coccoides group | 8 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 12 | 5 | 5 |

| C clostriiforme | 7 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 4 | 3 |

| Bacteroides fragilis group | 7 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| B thetaiotaomicron | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| B distasonis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| B vulgatus | 7 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 5 | 5 |

| E biforme | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| F prausnitzii | 3 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 4 |

| P productus | 6 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 4 | 4 |

| L acidophilus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

C, caecum, CD, Crohn's disease; I, ileum, IC, indeterminate colitis; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; R, rectum; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Data are expressed as the number of patients with positive PCR for each target bacterium to the total number of patients in each group.

Quantitative analysis of bacterial DNA from Bacteroides vulgatus

Real‐time PCR was carried out for a quantitative analysis of Bacteroides vulgatus in ileum, caecum and rectum samples. The mean Ct values were used to generate the reference curve for each predicted number of DNA copy of Bacteroides vulgatus ATCC 8482. The concentration range 0.05–50 000 pg/tube corresponded to 1×101–1×107 cells/tube. In the reference curve, used to extrapolate the equivalent number of CFU of Bvulgatus in the biopsy specimens, R = 0.999 and the slope was −3.45.

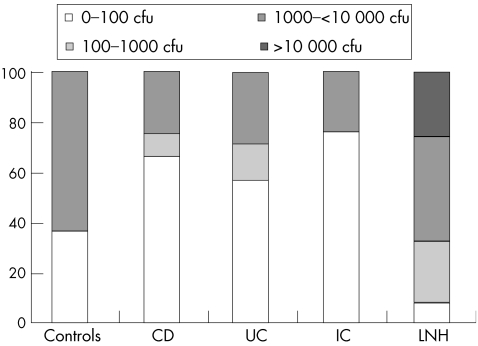

Figure 2 reports the results as the percentage of patients with different concentrations of Bacteroides vulgatus adherent to ileal mucosa calculated from cfu values (0–100, 100–1000 and 1000–10 000 cfu). Data obtained with the real‐time PCR technique confirm a significant reduction (p<0.05) of the percentage of samples positive for Bacteroides vulgatus in patients with IBD compared with controls. Up to 62.5% of controls and 42% of patients with LNH showed high concentrations of bacteria (1000–10 000 and >10 000 cfu), whereas lower concentrations (0–100 cfu) were found in biopsy specimens of patients with IBD, reaching 67% in patients with Crohn's disease, 57% in patients with ulcerative colitis and 75% in patients with indeterminate colitis. The trend in the quantitative analysis of Bacteroides vulgatus carried out in caecum and rectum biopsy specimens showed only slight variations in the number of cfu in comparison with that observed in ileum specimens (data not reported).

Figure 2 Percentage of patients with different concentrations of Bacteroides vulgatus adherent to ileal mucosa biopsy specimens. CD, Crohn's disease; cfu, colony forming units; IC, indeterminate colitis; LNH, lymphonodular hyperplasia; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Discussion

In humans, the composition of the flora is individual but stable, and differs between the stomach and upper bowel, lower small bowel, right colon and rectum.6,13 Moreover, the flora recovered from faeces is also different from mucosa‐associated or intraepithelial flora.6,21 The resident microbiota has a critical role in modulating the immune response of the gut as well as in the initiation and perpetuation of IBD. In the normal host, the protective cell‐mediated and humoral immune responses to enteropathogenic microorganisms are allowed to proceed, whereas responses to microorganisms of the indigenous flora are prevented. Differently, under conditions of chronic intestinal inflammation, this homeostasis seems to be disrupted, and the commensal flora seem to act as a surrogate bacterial pathogen: the lifelong inflammation in chronic IBD occurs because the host response in unable to eliminate the flora.31 Several lines of evidence in adults and in various animal models emphasise the role of the endogenous normal intestinal microflora in the aetiology of IBD.12,13,32

This study represents the first report investigating the intestinal microflora in paediatric patients with IBD as well as in children with symptoms suggesting IBD but exhibiting a predominant pattern of ileal LNH. We chose to analyse the mucosa‐associated microflora, as it is strictly joined to epithelial and immune cells and could have a central role in the pathogenesis of IBD. 21,29 Using a simple and reliable protocol of biopsy treatment, in which the overlying mucus layer was removed, we found a higher number of mucosa‐associated facultative‐anaerobic and aerobic bacteria in the ileum, caecum and rectum of children with IBD and INH than in controls, with the highest numbers found in patients with indeterminate colitis and Crohn's disease. However, in some instances, we found a great individual variability in the concentrations of mucosa‐associated bacteria, in particular, Gram‐positive bacteria, within the different groups of patients examined. As the age of our patients was far beyond the first 12 months, we could exclude any effect of age on the composition of the luminal microflora. Indeed, it is widely known that in the infant the establishment of the microflora is paralleled by maturing intestinal anatomy and physiology, with birth and weaning representing key stages at which bacteria colonise and species are established.5

Our findings are in agreement with those of other authors who showed that in adults, the mucosal surface of controls was essentially sterile and that the concentrations of mucosa‐associated bacteria were increased in IBD,12,21 although some previous microbiological studies had reported no or little difference in bacterial concentrations between patients with IBD and controls.33,34,35 This discrepancy could be attributed to the different experimental conditions used in the studies, including transport and washing, handling conditions, biopsy sampling and detection procedures, as well as molecular probes used, and to the fact that location and grade of mucosa inflammation might also have influenced the bacterial concentration.

Data analysis of the different mucosa‐associated bacterial species detected showed a generalised similar distribution of bacterial isolates among all patient groups, even though the highest heterogeneity of species was found in the ileal mucosa of patients with Crohn's disease. Interestingly, the detection of bacterial species among all patient groups showed that E coli was isolated in patients with IBD and in controls, but its loading associated with intestinal mucosa in patients with IBD resulted in a noticeable increase (data not shown). As already postulated for some adherent–invasive E coli strains,18,19,20,21 the role of Klebsiella spp in the pathogenesis of IBD and LNH disorders should be further investigated. Altered mucosal glycosylation in IBD36 could modify the interactions between the mucosa and microbial adhesins, thus selecting particular bacterial strains from the commensal microbiota.

As in previous reports,37,38 we were unable to isolate pathogenic bacteria, such as Yersinia spp, Campylobacter spp or L monocytogenes species and yeasts, supporting the finding that no specific pathogen is generally involved in IBD.

By using DNA‐based molecular techniques, marked differences were seen in the occurrence of anaerobic species in ileum, caecum and rectum biopsy specimens from patients with IBD only; qualitative and quantitative detection of Bacteroides vulgatus showed a reduction of this microorganism in samples from patients with Crohn's disease and indeterminate colitis. An intriguing result was the marked increase in Prevotella spp only in the rectum of patients with ulcerative colitis, in accordance with the prevailing inflammatory involvement of the rectum in this disorder.

Although some cultures as well as culture‐independent studies have shown a possible increase in Bacteroides spp in adult patients with Crohn's disease,12,39,40 other reports have shown that IBD is associated with loss of some anaerobic bacteria related to the intestinal mucosa.13,15,41 The lack of detection of Bacteroides vulgatus from all locations of the mucosa in patients with indeterminate colitis is in agreement with the experimental observations of Waidmann et al,17 who suggested a protective role of this species against Ecoli‐induced colitis, supporting the importance of this bacterium in the “physiological inflammation”.31 Our overall data analysis showed that in patients with indeterminate colitis, the total absence of Bacteroides vulgatus and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron or their decrease in concentration were almost always coupled with the occurrence of Klebsiella spp. The low recovery of the Bacteroides group in patients with Crohn's disease and the associated‐presence of E coli strains may represent an interesting finding that should be further investigated. These findings strongly support the hypothesis that in patients with IBD a change in the microbial ecosystem, consisting of an altered colonisation of the gut mucosa by aerobic and anaerobic species, may occur.

The results of this study contribute to the understanding of modifications in the bacterial flora among patients with IBD and controls. Indeed, these data support the hypothesis that the global composition of the intestinal microflora rather than the presence of single pathogens can be relevant for the aetiology and pathogenesis of paediatric IBD.41 It is conceivable that changes in the glycoprotein components of the intestinal mucosa,42,43,44 which characterise IBD, could determine loss or unmasking of receptors leading to a different selection of microorganisms present in the intestinal ecosystem. Hence, the decrease in Bacteroides vulgatus could be attributed to a lower association of this bacterium to gut mucosa, thus hindering its putative protective role, whereas the enhanced presence of E coli in patients with IBD could be the result of the availability of new binding receptors. Moreover, knowledge of the distribution of microorganisms isolated from the gut of patients with IBD could be helpful not only to identify antibiotic targets, but also to obtain a therapeutic manipulation of the gut flora by probiotic or prebiotic strategies. However, this study is based on a small sample of patients and many comparisons, and thus significance tests, have been made. The statistical significance of these results should be viewed with caution. Some apparently significant results could be due to the large number of tests performed, whereas some statistically non‐significant results may be due to the small sample sizes. Nevertheless, these results show that further studies are required to investigate the role of bacterial species found in paediatric patients with IBD, as well as putative differences in their virulence potential.

Abbreviations

ATCC - American Type Culture Collection

cfu - colony forming units

IBD - inflammatory bowel disease

LNH - lymphonodular hyperplasia

PCR - polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by MIUR grants to MPC and SS.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Dunne C. Adaptation of bacteria to the intestinal niche: probiotics and gut disorders. Inflamm Bowel Dis 20017136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooper L V, Gordon J I. Commensal host‐bacterial relationships in the gut. Science 20012921115–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanahan F. The host‐microbe interface within the gut. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 200216915–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holm H, Powrie F. Dendritic cells and intestinal bacterial flora: a role for localized mucosal immune response. J Clin Invest 2003112648–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guarner F, Malagelada J R. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet 2003361512–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marteau P, Lepage P, Mangin I.et al Gut flora and inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 20042018–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pirzer U, Schonhaar A, Fleischer B.et al Reactivity of infiltrating T lymphocytes with microbial antigens in Crohn's disease. Lancet 19913381238–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macpherson A, Khoo U Y, Forgacs I.et al Mucosal antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease are directed against intestinal bacteria. Gut 199638365–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furrie E, Macfarlane S, Cummings J H.et al Systemic antibodies towards mucosal bacteria in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease differentially activate the innate immune response. Gut 20045391–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hausmann M, Kiessling S, Mestermann S.et al Toll‐like receptors 2 and 4 are up‐regulated during intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology 20021221987–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hugot J P, Chamaillard M, Zouali H.et al Association of NOD2 leucine‐rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature 2001411599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swidsinski A, Ladhoff A, Pernthaler A.et al Mucosal flora in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 200212244–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seksik P, Rigottier‐Gois L, Gramet G.et al Alterations of the dominant faecal bacterial groups in patients with Crohn's disease of the colon. Gut 200352237–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schultsz C, Van Den Berg F M, Ten Kate F W.et al The intestinal mucus layer from patients with inflammatory bowel disease harbours high numbers of bacteria compared with controls. Gastroenterology 19991171089–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleessen B, Kroesen A J, Buhr H J.et al Mucosal and invading bacteria in patients with inflammatory bowel disease compared with controls. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002371034–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rath H C, Wilson K H, Sartor R B. Differential induction of colitis and gastritis in HLA‐B27 transgenic rats selectively colonized with Bacteroides vulgatus or Escherichia coli.Infect Immun 1999672969–2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waidmann M, Bechtold O, Frick J S.et al Bacteroides vulgatus protects against Escherichia coli‐induced colitis in gnotobiotic interleukin‐2 deficient mice. Gastroenterology 2003125162–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darfeuille‐Michaud A, Boudeau J, Bulois P.et al High prevalence of adherent‐invasive Escherichia coli associated with ileal mucosa in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2004127412–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boudeau J, Glasser A L, Masseret E.et al Invasive ability of an Escherichia coli strain isolated from the ileal mucosa of a patient with Crohn's disease. Infect Immun 1999674499–4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boudeau J, Barnich N, Darfeuille‐Michaud A. Type 1 pili‐mediated adherence of Escherichia coli strain LF82 isolated from Crohn's disease is involved in bacterial invasion of intestinal epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol 2001391272–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin H M, Campbell B J, Hart C A.et al Enhanced Escherichia coli adherence and invasion in Crohn's disease and colon cancer. Gastroenterology 200412780–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamboli C P, Neut C, Desreumaux P.et al Dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2004531–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kokkonen J, Karttunen T J. Lymphonodular hyperplasia on the mucosa of the lower gastrointestinal tract in children: an indication of enhanced immune response? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 20023442–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conti F, Borrelli O, Anania C.et al Chronic intestinal inflammation and seronegative spondyloarthropathy in children. Dig Liv Dis 200537761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geboes K, De Hertogh G. Indeterminate colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 20039324–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang R F, Cao W W, Cerniglia C E. PCR detection and quantitation of predominant anaerobic bacteria in human and animal fecal samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 1996621242–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Fujimoto J.et al Development of 16S rRNA‐gene‐targeted group‐specific primers for the detection and identification of predominant bacteria in human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002685445–5451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drasar B S, Roberts A K. Control of the large bowel microflora. In: Hill MJ, Marsh PD, eds. Human microbial ecology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 199095–100.

- 29.Lepage P, Seksik P, Sutren M.et al Biodiversity of the mucosa‐associated microbiota is stable along the distal digestive tract in healthy individuals and patients with IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis 200511473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore W E C, Holdeman L V. Human fecal flora: the normal flora of 20 Japanese‐Hawaiians. Appl Microbiol 197427961–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haller D, Jobin C. Interaction between resident luminal bacteria and the host: can a healthy relationship turn sour? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 200438123–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elson C O, Sartor R B, Tennyson G S.et al Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 19951091344–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartley M G, Hudson M J, Swarbrick E T.et al The rectal mucosa‐associated microflora in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Med Microbiol 19923696–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hudson M J, Hill M J, Elliott P R.et al The microbial flora of the rectal mucosa and faeces of patients with Crohn's disease before and during antimicrobial chemotherapy. J Med Microbiol 198418335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poxton I R, Brown R, Sawyerr A.et al Mucosa‐associated bacterial flora of the human colon. J Med Microbiol 19974685–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell B J, Yu L G, Rhodes J M. Altered glycosylation in inflammatory bowel disease: a possible role in cancer development. Glycoconj J 200118851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Kruiningen H J. Lack of support for a common etiology in Johne's disease of animals and Crohn's disease in humans. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19995183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen W, Li D, Wilson I.et al Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae by polymerase chain reaction‐enzyme immunoassay in intestinal mucosal biopsies from patients with inflammatory bowel disease and controls. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 200217987–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruseler‐van Embden J G, Both‐Patoir H C. Anaerobic Gram‐negative faecal flora in patients with Crohn's disease and healthy subjects. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 198349125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giaffer M H, Holdsworth C D, Duerden B I. The assessment of faecal flora in patients with inflammatory bowel disease by a simplified bacteriological technique. Med Microbiol 199135238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ott S J, Musfeldt M, Wenderoth D F.et al Reduction in diversity of the colonic mucosa associated bacterial microflora in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 200453685–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobs L R, Huber P W. Regional distribution and alterations of lectin binding to colorectal mucin in mucosal biopsies from controls and subjects with inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Invest 198575112–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoskins L C, Agustines M, McKee W B.et al Mucin degradation in human colon ecosystems. Isolation and properties of fecal strains that degrade ABH blood group antigens and oligosaccharides from mucin glycoproteins. J Clin Invest 198575944–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corfield A P, Wagner S A, Clamp G R.et al Mucin degradation in the human colon: production, sialidase, sialate O‐acetylesterase, N‐acetylneuraminate lyase, arylesterase, and glycosulfatase activities by strains of fecal bacteria. Infect Immun 1998603971–3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]