Abstract

Background

Exogenous use of the intestinal hormone glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) lowers glycaemia by stimulation of insulin, inhibition of glucagon, and delay of gastric emptying.

Aims

To assess the effects of endogenous GLP‐1 on endocrine pancreatic secretion and antro‐pyloro‐duodenal motility by utilising the GLP‐1 receptor antagonist exendin(9‐39)amide (ex(9‐39)NH2).

Methods

Nine healthy volunteers underwent four experiments each. In two experiments with and without intravenous infusion of ex(9‐39)NH2 300 pmol/kg/min, a fasting period was followed by intraduodenal glucose perfusion at 1 and 2.5 kcal/min, with the higher dose stimulating GLP‐1 release. Antro‐pyloro‐duodenal motility was measured by perfusion manometry. To calculate the incretin effect (that is, the proportion of plasma insulin stimulated by intestinal hormones) the glycaemia observed during the luminal glucose experiments was mimicked using intravenous glucose in two further experiments.

Results

Ex(9‐39)NH2 significantly increased glycaemia during fasting and duodenal glucose. It diminished plasma insulin during duodenal glucose and significantly reduced the incretin effect by approximately 50%. Ex(9‐39)NH2 raised plasma glucagon during fasting and abolished the decrease in glucagon at the high duodenal glucose load. Ex(9‐39)NH2 markedly stimulated antroduodenal contractility. At low duodenal glucose it reduced the stimulation of tonic and phasic pyloric motility. At the high duodenal glucose load it abolished pyloric stimulation.

Conclusions

Endogenous GLP‐1 stimulates postprandial insulin release. The pancreatic α cell is under the tonic inhibitory control of GLP‐1 thereby suppressing postprandial glucagon. GLP‐1 tonically inhibits antroduodenal motility and mediates the postprandial inhibition of antral and stimulation of pyloric motility. We therefore suggest GLP‐1 as a true incretin hormone and enterogastrone in humans.

Keywords: glucagon‐like peptide 1, exendin(9‐39), incretin, enterogastrone, pyloric motility

Glucagon‐like peptide‐1(7–36)amide (GLP‐1) is a gut born hormone released from L cells in response to nutrients and, especially, carbohydrates. GLP‐1 has been shown in vitro and in vivo to reduce glucagon and to stimulate insulin secretion.1,2,3,4 A dominant gastrointestinal action of synthetic GLP‐1 is inhibition of gastroduodenal and stimulation of pyloric motility,5,6 resulting in a delay in gastric emptying and decreased glycaemic excursions.3,4,7,8,9 These combined effects improve glucose tolerance providing the rationale for the therapeutic potential of GLP‐1 analogues in the treatment of diabetes mellitus.

Most of our understanding of the effects of GLP‐1 on postprandial glucose homoeostasis is based on studies using synthetic GLP‐1 whereas little is known of endogenously released GLP‐1. The availability of a powerful GLP‐1 receptor antagonist exendin(9‐39)amide (ex(9‐39)NH2) allows us to evaluate whether GLP‐1 acts as an incretin hormone and/or enterogastrone in humans. The usefulness of the antagonist became evident in initial studies demonstrating that endogenously released peptide enhances postprandial insulin release in rats.10,11 With this antagonist introduced in humans, evidence was found that the pancreatic α cell is under tonic inhibitory control by fasting levels of GLP‐1.12 Blockade of GLP‐1 by ex(9‐39)NH2 after an oral glucose meal resulted in a 35% increase in postprandial glucose excursions.13

To date, the exact role of GLP‐1 in the regulation and interplay of the endocrine pancreas and gastroduodenal motility is unclear. To shed more light onto this important issue, we used the GLP‐1 antagonist to define the physiological actions of endogenously released GLP‐1 on the pancreas and upper gastrointestinal motility in humans. We stimulated GLP‐1 release by graded duodenal glucose perfusion, utilising caloric loads below and above the threshold for GLP‐1 release.14 We avoided the gastric route of glucose entering the intestine, excluding interferences caused by putatively accelerated gastric emptying in response to ex(9‐39)NH2.

Material and methods

Subjects

Nine healthy male volunteers, 22–28 years of age, body mass index 22–24 kg/m2, participated in the studies. None was taking any medication, and all were free of gastrointestinal symptoms or any systemic disease. The studies were approved by the local ethics committee and all participants provided written informed consent.

Experimental protocol

All experiments were performed in a double blind fashion on different days after an overnight fast. Experiments in respective individuals were separated by at least seven days (range 7–78 days). Each subject underwent two series of two experiments each in random order. In the first series, volunteers swallowed a nine lumen duodenal sleeve/side hole catheter with its tip positioned at the ligament of Treitz. The catheter was used for continuous recording of antro‐pyloro‐duodenal motility and for duodenal perfusion of glucose solution. An interdigestive period of 60 minutes was followed by intraduodenal glucose perfusion (1 kcal/ml) at 1 kcal/minute for 60 minutes and at 2.5 kcal/minute for another 120 minutes. These glucose loads are below and above the threshold for GLP‐1 release, respectively.14 Starting 30 minutes before duodenal glucose perfusion in the fasting state, ex(9‐39)NH2 300 pmol/kg/min12 or saline was infused intravenously. During the last 60 minutes of the experiments, saline was infused instead of ex(9‐39)NH2 to allow for recovery of effects.

In the second series, two further experiments without duodenal intubation were performed in each subject to calculate the incretin effect (that is, proportion of total postprandial insulin secretion stimulated by intestinal hormones). The incretin effect was quantified by comparing insulin and C peptide responses during the duodenal glucose load and during isoglycaemic intravenous glucose infusion. The time course of blood glucose during the duodenal glucose load both with and without intravenous ex(9‐39)NH2 was mimicked by intravenous glucose. Glucose 20% was intravenously infused, and infusion rate adjustments were performed according to a modified method of DeFronzo and colleagues15 based on five minute blood glucose determinations. Isoglycaemic intravenous glucose infusions provide a measure of β cell secretory responses to the glycaemic stimulus without superimposed incretin effects. The difference in incremental β cell secretory responses (SR) to both of these stimuli represents the action of incretin factors and is expressed as the percentage of the physiological response to duodenal glucose, which is taken as the denominator (100%)16:

Incretin effect = (SRduodenal − SRisoglycaemic iv) / SRduodenal × 100%

Samples of arterialised blood (“heated hand”12) were taken at 10 minute intervals throughout each experiment. Blood was collected in ice chilled EDTA tubes containing aprotinin 1000 kallikrein inhibitory units/ml blood and centrifuged immediately. Plasma was stored at −20°C until assayed.

Motility recording

Perfusion manometry was recorded using a nine lumen duodenal sleeve/side hole catheter (Dentsleeve, South Australia, Australia). The manometric assembly incorporated a 4.5 cm sleeve sensor, two antral side holes (2 cm apart), and three duodenal side holes (2 cm apart), beginning at the proximal and distal ends of the sleeve, respectively. Two further side holes were positioned along the sleeve spaced 1.5 cm apart. An additional lumen located 12 cm distal to the sleeve sensor was used for duodenal perfusion.

The position of the catheter with the sleeve array straddling the pylorus was monitored by measuring the transmucosal potential difference between the distal antral and proximal duodenal port.14 A difference of at least −15 mV indicated the correct transpyloric position of the tube.

Motility channels were perfused at a rate of 0.3 ml/min using a low compliance pneumohydraulic pump (Arndorfer Medical Specialists, Greendale, Wisconsin, USA). Data were sampled at 8 Hz on a multichannel chart system (Medical Measurement Systems, Enschede, the Netherlands).

Analysis of motility tracings

Analysis of contractile events was performed as previously described.6,17 Only peaks with amplitudes of at least 10 mm Hg and durations of at least two seconds were considered true pressure waves. Antral phase III was defined as the occurrence of regular pressure waves at a frequency ⩾3/minute for at least two minutes in the antrum, propagated aborally. Data were analysed in 10 minute intervals separately for the antrum and duodenum by summarising (frequency, motility index) or averaging (amplitude) the values derived from the antral and duodenal side holes, respectively. Motility indices were determined as area under the pressure waves and expressed as mm Hg×s/min.

Isolated pyloric pressure waves (IPPW) were defined as pressure waves registered by the sleeve with simultaneous pressure waves maximally in one sleeve‐side hole in the absence of associated (±3 seconds) waves in the adjacent antral and duodenal side holes. Pyloric tone was measured as the difference in basal pressures recorded by the sleeve and by the antral side hole at the proximal end of the sleeve.18 Basal pressures (that is, mean pressures after excluding pressure waves) were obtained for each minute and were used to calculate mean pyloric tone.

Exendin(9‐39)amide

Synthetic ex(9‐39)NH2 was purchased from PolyPeptide Laboratories (Wolfenbüttel, Germany). Peptide content amounted to 90.6% with a peptide purity >98%. High performance liquid chromatography showed a single peak for ex(9‐39)NH2. The peptide was dissolved in 1% human serum albumin, filtered through 0.2 μm nitrocellulose filters, and stored at −70°C. Samples were tested for pyrogens and bacterial growth and no contamination with bacterials or endotoxins was detected.

Determinations and assays

Blood glucose concentrations were measured by the glucose oxidase method (YSI 1500G; Schlag, Bergisch‐Gladbach, Germany). Plasma insulin was measured by the Abbott Imx Microparticle Enzyme Immunoassay, with an average intra‐assay coefficient of variation of 5%. Immunoreactivities of C peptide, glucagon, and glucose dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) were analysed by commercially available radioimmunoassay kits (Biermann, Bad Nauheim, Germany). Immunoreactivity of GLP‐1 was measured using the specific polyclonal antibody GA1178 (Affinity Research, Nottingham, UK).14 Immunoreactivities of GLP‐1 were extracted from plasma samples on C‐18 cartridges using acetonitrile for elution of samples. The antiserum did not cross react with ex(9‐39)NH2, GIP, pancreatic glucagon, glicentin, oxyntomodulin, or GLP‐2. The detection limit of the assay was 0.25 pmol/l. Intra‐ and inter‐assay coefficients of variation were 3.6% and 10.7%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Power calculations were performed based on a two tailed paired t test at the 5% significance level. With respect to the incretin effect, a sample size of nine subjects ensured a power of 86% to yield a statistically significant difference of at least 20%. This calculation was based on an intersubject coefficient of variation of 0.27.19 With respect to pyloric tone, a sample size of nine subjects ensured a power of 94% to yield a statistically significant difference of at least 2 mm Hg. This calculation was based on an intersubject coefficient of variation of 0.47 derived from experiments with duodenal lipid perfusion.6

All values are expressed as mean (SEM). Parameters were separately analysed for the first 30 minute period during the fasting state and for each 60 minute period of duodenal glucose perfusion. Pyloric tone was calculated as change from basal, the latter being determined as mean pyloric tone during the basal period before starting the intravenous infusions. Differences in plasma hormones and glucose compared with the basal state were calculated as integrated values over basal (area under the response curve; AUC). Basal levels were determined as the mean of two basal values just before the start of each experiment. All samples were first tested for normality by the Komolgoroff‐Smirnoff test. Differences between experimental sets for each parameter were analysed by two way repeated measures ANOVA using intravenous infusion and duodenal perfusion as factors. With respect to each parameter analysed, ANOVA did not indicate a significant interaction between intravenous infusion and rate of intraduodenal glucose. Thus the effect of intravenous infusion did not depend on what level of glucose perfusion was present. When ANOVA indicated differences, a Student‐Newman‐Keuls multicomparison test was performed. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05.

Results

Plasma immunoreactivities of gastrointestinal peptides and blood glucose

Duodenal glucose perfusion

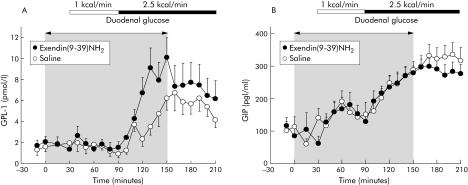

GLP‐1 plasma levels did not increase during perfusion of duodenal glucose at 1 kcal/min, in contrast with 2.5 kcal/min which elicited an increase in GLP‐1 (fig 1 A). Compared with saline, ex(9‐39)NH2 did not influence GLP‐1 plasma levels during the fasting state or with low duodenal glucose but approximately doubled plasma GLP‐1 during the high duodenal glucose load (fig 1A, table 1).

Figure 1 Effects of intravenous exendin(9‐39)NH2 300 pmol/kg/min on plasma immunoreactivities of glucagon‐like peptide 1(GLP‐1) (A) and glucose dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) (B) during fasting and with duodenal glucose perfusion of 1 and 2.5 kcal/min in nine healthy volunteers. Intravenous infusions were discontinued after 150 minutes. For statistical analysis, see table 1.

Table 1 Effect of duodenal glucose perfusion on blood glucose and plasma immunoreactivities of gastrointestinal peptides with and without intravenous exendin(9‐39)NH2.

| Intravenous infusion | Duodenal glucose perfusion rate (60 min each) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 kcal/min | 2.5 kcal/min | 2.5 kcal/min (recovery) | ||||

| Saline iv | Ex(9‐39) | Saline iv | Ex(9‐39) | Saline iv | Saline iv | |

| GLP‐1 (pmol/l/60 min) | −0.5 (1.3) | −0.4 (1.5) | 13 (4.5) | 29 (7.4)* | 25 (5.5) | 30 (10) |

| GIP (pg/ml/60 min) | 247 (52) | 337 (90) | 801 (116) | 904 (121) | 1319 (166) | 1151 (93) |

| Blood glucose (mmol/l/60 min) | 6.4 (0.5) | 8.3 (0.9)* | 13 (1.1) | 18 (1.6)* | 7.4 (1.0) | 9.2 (1.3) |

| Insulin (mU/l/60 min) | 62 (8.3) | 54 (9.5) | 287 (40) | 220 (38)* | 194 (27) | 195 (35) |

| C‐peptide (ng/ml/60 min) | 9.1 (0.7) | 7.6 (0.8) | 34 (5.8) | 28 (4.9) | 31 (5.0) | 33 (6.7) |

| Glucagon (pg/ml/60 min) | −80 (11) | 15 (16)* | −138 (25) | 5.4 (23)* | −156 (31) | −46 (25)* |

iv, intravenous; GLP‐1, glucagon‐like peptide 1; GIP, glucose dependent insulinotropic polypeptide.

Mean (SEM) of AUC over basal during each 60 minute perfusion period (n = 9). Differences were compared using two way repeated measures ANOVA employing individual incremental or decremental values over basal during the respective periods.

*p<0.05 versus saline iv.

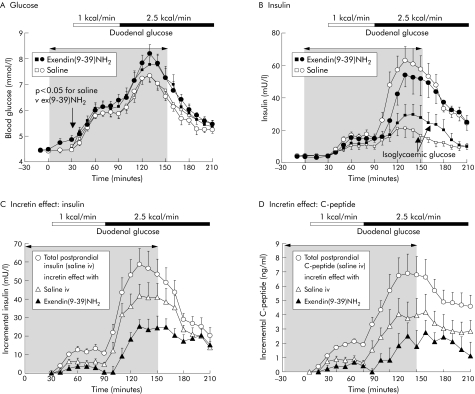

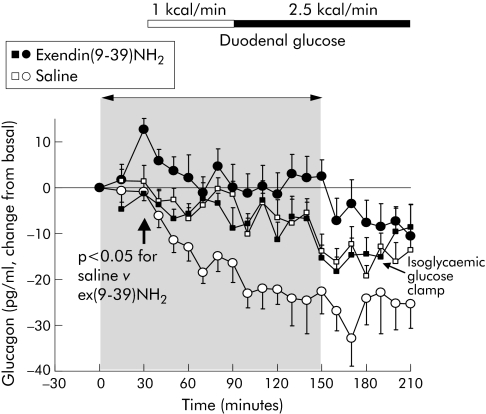

Even during fasting, ex(9‐39)NH2 significantly increased blood glucose (4.9 (0.16) v 4.4 (0.07); p<0.05 v saline control) (fig 2A). This was accompanied by a significant increase in basal plasma glucagon levels (fig 3) but not plasma insulin (fig 2B).

Figure 2 Effects of intravenous exendin(9‐39)NH2 300 pmol/kg/min on blood glucose (A) and plasma immunoreactivity of insulin (B) during fasting and with duodenal glucose perfusion of 1 and 2.5 kcal/min in nine healthy volunteers. Intravenous infusions were discontinued after 150 minutes. Square symbols represent data during isoglycaemic intravenous glucose, mimicking blood glucose levels of the two experiments with saline and exendin(9‐39)NH2 to calculate the incretin effect (C, D). The incretin effect was calculated as the difference in incremental insulin (C) and C peptide (D) plasma levels between duodenal glucose perfusion and the respective isoglycaemic clamp experiment. For statistical analysis, see tables 1 and 2.

Figure 3 Effects of intravenous exendin(9‐39)NH2 300 pmol/kg/min on plasma immunoreactivities of glucagon during fasting and with duodenal glucose perfusion of 1 and 2.5 kcal/min in nine healthy volunteers. Intravenous infusions were discontinued after 150 min. Square symbols indicate data for plasma glucagon during isoglycaemic glucose clamps, mimicking blood glucose levels in the two experiments with saline and exendin(9‐39)NH2 For statistical analysis, see table 1.

Duodenal glucose perfusion dose dependently enhanced blood glucose levels (fig 2A). This was paralleled by an increase in plasma insulin and a decrease in plasma glucagon (figs 2B, 3). Compared with saline, ex(9‐39)NH2 significantly increased blood glucose, during both the low and high duodenal glucose perfusion, by 29% and 31%, respectively (fig 2, table 1). Plasma insulin significantly decreased with ex(9‐39)NH2 during high duodenal glucose but remained unchanged during the low duodenal glucose load. After cessation of ex(9‐39)NH2, blood glucose and plasma insulin levels reached those obtained with saline.

During duodenal perfusion of glucose, plasma glucagon levels steadily decreased throughout the experiments (fig 3). This effect was completely abolished by ex(9‐39)NH2. However, accounting for the effects on fasting levels of glucagon, ex(9‐39)NH2 did not change the glucagon response to duodenal glucose at 1 kcal/min. The further decrease in plasma glucagon with duodenal glucose at 2.5 kcal/min, however, was completely blocked by ex(9‐39)NH2. This was reversible after cessation of ex(9‐39)NH2. Endogenous GLP‐1 not only tonically suppressed fasting glucagon but further inhibited postprandial glucagon release.

Isoglycaemic intravenous glucose infusion

During isoglycaemic clamp experiments, blood glucose obtained with intravenous glucose reproduced values with duodenal glucose, with a mean r2 of 0.88 (0.01) (fig 2A, table 2). Compared with duodenal glucose perfusion, plasma levels of insulin and C peptide were markedly diminished during isoglycaemic clamping (fig 2B, table 2). The resulting incretin effect (that is, the proportion of insulin secretion related to intestinal peptides) significantly increased during the high compared with the low duodenal glucose load, amounting to 48 (8.2)% and 70 (5.6)% based on plasma insulin levels and 41 (8.5)% and 51 (9.1)% based on plasma C peptide levels (fig 2C, D; table 2). Ex(9‐39)NH2 significantly diminished the incretin effect at both duodenal glucose loads by approximately 50%. This effect was reversible after cessation of ex(9‐39)NH2.

Table 2 Isoglycaemic clamp studies mimicking glycaemia. Blood glucose and β cell response during intravenous glucose infusion.

| Saline iv | Ex(9‐39) iv | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duodenal glucose (kcal/min) | 1 | 2.5 | 2.5 (recovery) | 1 | 2.5 | 2.5 (recovery) | |

| Blood glucose (mmol/l/60 min) | 7.0 (0.6) | 13 (1.3) | 7.6 (0.8) | 8.7 (0.8)* | 17 (1.4)* | 8.6 (1.2) | |

| Intravenous glucose load (kcal) | 54 (2.9) | 98 (10) | 75 (10) | 59 (5.8) | 106 (16) | 95 (17) | |

| Insulin (mU/l/60 min) | 31 (7.3) | 84 (18) | 43 (8.8) | 40 (8.6) | 118 (30)* | 77 (24)* | |

| C peptide (ng/ml/60 min) | 5.2 (0.7) | 15 (2.8) | 13 (1.8) | 5.8 (1.0) | 20 (4.9)* | 21 (7.4)* | |

| Incretin effect based on insulin (%) | 48 (8.2) | 70 (5.6) | 76 (4.4) | 23 (6.0)* | 36 (5.2)* | 58 (3.9)* | |

| Incretin effect based on C peptide (%) | 41 (8.5) | 51 (9.1) | 54 (8.8) | 19 (11)* | 22 (11)* | 36 (11)* | |

Ex(9‐39), exendin(9‐39)amide; iv, intravenous.

Mean (SEM) of AUC over basal during each 60 minute infusion period (n = 9). The incretin effect reflects the difference in incremental β cell secretory response between duodenal glucose, as shown in table 1, and isoglycaemic intravenous glucose shown here. Differences were compared using two way repeated measures ANOVA employing individual incremental or decremental values over basal during the respective periods.

*p<0.05 versus experiments mimicking glycaemia during duodenal glucose and saline iv.

Antroduodenal and pyloric motility

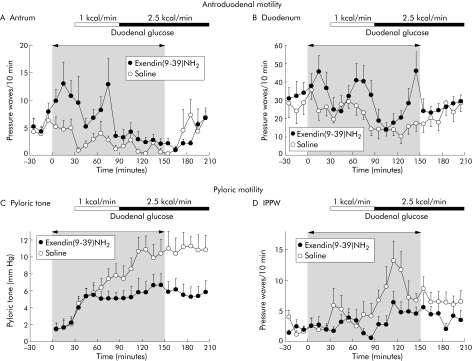

Duodenal glucose dose dependently inhibited antral and duodenal contractility and increased the tonic and phasic motility of the pylorus (fig 4, table 3). During intravenous infusion of the GLP‐1 receptor antagonist ex(9‐39)NH2, a total of 11 antral phase IIIs occurred in eight of nine volunteers followed by a short phase I, compared with two phase IIIs during saline control. Six of these antral phase IIIs occurred within the 30 minute priming period under ex(9‐39)NH2 during the fasting state. Even with excluding phase III activities from further analysis, ex(9‐39)NH2 significantly increased the number and motility indices of antral and duodenal pressure waves during the fasting state and during both duodenal glucose loads (fig 4, table 3). This stimulating effect disappeared at cessation of ex(9‐39)NH2, suggesting an inhibitory role of endogenous GLP‐1 in this context. Amplitude and duration of antroduodenal pressure waves remained unaltered by ex(9‐39)NH2 (data not shown). However, in spite of its stimulating effect, ex(9‐39)NH2 did not prevent inhibition of antroduodenal contractility by duodenal glucose, which occurred to a similar extent as during saline.

Figure 4 Frequencies of pressure waves in the antrum (A) and duodenum (B), and pyloric tone (C) and isolated pyloric pressure waves (IPPW) (D) in response to intravenous infusions of saline and exendin(9‐39)NH2 300 pmol/kg/min during fasting and with duodenal glucose perfusion at 1 and 2.5 kcal/min in nine healthy volunteers. Intravenous infusions were discontinued after 150 minutes. For statistical analysis, see table 3.

Table 3 Effects of intravenous exendin(9‐39)NH2 on antro‐pyloro‐duodenal motility during duodenal glucose perfusion at different rates.

| IV infusion | Duodenal glucose perfusion rate (60 min each) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 kcal/min | 2.5 kcal/min | 2.5 kcal/min (recovery) | ||||

| Saline iv | Ex(9‐39) | Saline iv | Ex(9‐39) | Saline iv | Saline iv | |

| Antral motility | ||||||

| Pressure waves (No/60 min) | 13 (3.3) | 46 (7.5)* | 8.0 (2.6) | 16 (3.7)* | 24 (6.3) | 20 (4.7) |

| Motility index (mm Hg×s/60 min) | 4498 (1622) | 9954 (2645)* | 364 (144) | 1016 (250)* | 1549 (461) | 2372 (901) |

| Amplitude (mm Hg) | 49 (11) | 49 (6.9) | 21 (4.0) | 25 (6.2) | 31 (6.8) | 37 (7.7) |

| Duodenal motility | ||||||

| Pressure waves (No/60 min) | 141 (10) | 195 (17)* | 74 (12) | 151 (11)* | 131 (20) | 143 (17) |

| Motility index (mmHg×s/60 min) | 7118 (1278) | 9785 (1376)* | 3463 (612) | 5711 (804)* | 5416 (982) | 5776 (877) |

| Amplitude (mm Hg) | 23 (0.8) | 24 (1.5) | 21 (2.0) | 22 (1.7) | 22 (1.9) | 24 (1.2) |

| Pyloric motility | ||||||

| IPPW (No/60 min) | 26 (5.5) | 14 (2.7) | 53 (9.5) | 24 (6.2)* | 47 (9.2) | 28 (8.1)* |

| Pyloric tone (mm Hg) | 6.2 (1.0) | 5.0 (0.8) | 9.8 (1.3) | 5.8 (1.1)* | 11 (1.5) | 6.3 (1.3)* |

IPPW, isolated pyloric pressure waves; iv, intravenous.

Mean (SEM) of actual values and of values over basal (pyloric tone) during each 60 minute perfusion period. Values for pressure waves and motility indices represent the sum of two antral and three duodenal side holes, respectively (n = 9).

Differences were compared using two way repeated measures ANOVA employing individual incremental or decremental values during the respective periods.

*p<0.05 versus saline iv.

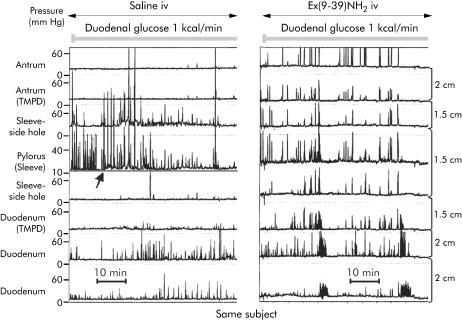

Stimulation of pyloric tone by duodenal glucose was inhibited by ex(9‐39)NH2 (fig 4, table 3). Although the low duodenal glucose load also enhanced pyloric tone with ex(9‐39)NH2 during the first 30 minutes of perfusion, the GLP‐1 antagonist prevented the further increase in tone during the last 30 minutes of this period and completely abolished the tonic response to duodenal glucose at 2.5 kcal/min. Furthermore, the increase in IPPW resembling the phasic response of the pylorus to duodenal glucose perfusion was significantly inhibited by ex(9‐39)NH2. The typical pattern of antro‐pyloro‐duodenal motility seen with ex(9‐39)NH2 infusion is demonstrated in fig 5.

Figure 5 Manometric tracings of the same individual showing the effects of intravenous (iv) infusion of saline (left panel) and exendin(9‐39)NH2 300 pmol/kg/min (right panel) during duodenal glucose perfusion at 1 kcal/min. With iv saline, duodenal glucose at 1 kcal/min exerted inhibition of antral motility, tonic elevation in basal pyloric pressure (arrow), and induced isolated pyloric pressure waves. With iv ex(9‐39)NH2, marked antral contractility was observed leading to two aborally propagated antral phase IIIs. TMPD, transmucosal potential difference.

Discussion

This is the first study addressing the effects of endogenous GLP‐1 on release of insulin and pancreatic glucagon and on motility of the antro‐pyloro‐duodenal region in humans. The salient findings are as follows: (i) endogenous GLP‐1 significantly enhanced postprandial insulin secretion, suggesting GLP‐1 as a true incretin hormone in humans; (ii) fasting and postprandial GLP‐1 suppressed glucagon release; (iii) GLP‐1 mediated stimulation of pyloric motility induced by intestinal glucose; and (iv) GLP‐1 inhibited antro‐duodenal motility during the fasting and postprandial states, qualifying GLP‐1 as an enterogastrone. As GLP‐1 controls mechanisms with an impact on glycaemia, this may be relevant for type 2 diabetes mellitus for which a deficiency of bioactive GLP‐1 has been suggested.20

It is well known that duodenal glucose dose dependently increases blood glucose and plasma insulin, suppresses plasma glucagon, and induces a postprandial motor pattern with inhibition of antral and stimulation of pyloric motility.18,21,22 We examined the role of GLP‐1 as mediator of these effects.

Blockade of GLP‐1 action by ex(9‐39)NH2 raised blood glucose levels during the fasting state and during both loads of duodenal glucose. These data support findings that endogenous GLP‐1 significantly contributes to fasting and postprandial glucose homeostasis in humans.12,13 During fasting, plasma insulin remains unchanged under administration of the GLP‐1 receptor antagonist. On stimulations of endogenous GLP‐1 by duodenal glucose, however, ex(9‐39)NH2 reduced plasma insulin, thereby contributing to elevated plasma glucose levels. This argues in favour of GLP‐1 being a true incretin hormone in humans.

However, the experimental design needs careful consideration when interpreting data in this field. When glucose is delivered directly and continuously into the bowel, GLP‐1 promptly raises plasma insulin. When glucose is swallowed as a liquid test meal, interference with gastric emptying needs to be taken into account. To date, only one study in humans has addressed the effect of ex(9‐39)NH2 on glycaemia after an oral glucose meal. It showed an increase in incremental postprandial glucose by 35%, which is comparable with our results, and a paradoxical increase in plasma insulin.13 We found that blocking the action of GLP‐1 resulted in enhancement of postprandial glucagon secretion and also in stimulation of antral and inhibition of pyloric motility. Thus after an oral meal, increasing glucagon and acceleration of gastric emptying rate may result in higher postprandial glucose levels. Such glucose levels may stimulate insulin release, outweighing a putative inhibitory effect of the GLP‐1 antagonist on insulin secretion.

Calculation of the incretin effect from β cell secretory responses is based on the assumption that after glucose ingestion, the endocrine pancreas is stimulated by both the resulting elevation in plasma glucose and the additional stimulation by gastrointestinal (incretin) factors.23,24 Considering the reduced hepatic insulin extraction after enteral compared with intravenous glucose, C peptide may be a better quantitative estimate in determining the β cell secretory response than plasma insulin.25,26 Regarding plasma C peptide, the incretin effect (that is, postprandial insulin secretion triggered by intestinal hormones) rose with increasing intestinal glucose load, amounting to approximately 50% at the high dose of duodenal glucose. This mirrored previous findings by others.27,28,29 The fraction of the incretin effect attributable to GLP‐1 made up for approximately 50% with both duodenal glucose loads. It is remarkable that during infusion of the low duodenal glucose load, endogenous GLP‐1 significantly contributed to the incretin effect although plasma GLP‐1 was not significantly raised. This points to the high sensitivity of the pancreatic β cell to GLP‐1. GIP probably mediates the residual incretin effect remaining after blockade of GLP‐1. This is at least suggested by animal studies demonstrating a reduction in insulin secretion with GIP immunoadsorption, GIP antiserum, or GIP receptor antagonists by 20–70%.30,31,32,33 It is also in accordance with the known additive insulinotropic effect of GIP and GLP‐1 in healthy humans.34,35

The order of the intraduodenal infusions at 1 and 2.5 kcal/min was always the same in each experiment and we did not use a washout period in between. Therefore, we cannot exclude the fact that the low caloric glucose perfusion may have influenced parameters obtained at the high caloric perfusion rate. However, blood glucose and plasma insulin in the present study increased by nearly identical amounts and at a similar velocity compared with experiments with duodenal perfusion of glucose at 1.1 and 2.2 kcal/min performed on different days.14 Also, the third main outcome parameter, pyloric tone, promptly and dose dependently increased in our study, as has been shown previously including a washout period.18 Therefore, we abstained from a washout period in order to save ex(9‐39)NH2 which is very expensive. Moreover, the identical design except for the intravenous background infusions were done on different days. Thus the potential of an order effect may not explain the profound effects of ex(9‐39)NH2.

Previous in vitro experiments suggested indirect paracrine suppression of glucagon by somatostatin while revealing that GLP‐1 stimulates somatostatin secretion in isolated rat and human pancreatic islets and perfused pancreas preparations.36,37,38 Hitherto, the effects of endogenous GLP‐1 on postprandial glucagon release in humans were unknown. The increase in blood glucose with ex(9‐39)NH2 during fasting was accompanied by a significant increase in plasma glucagon in spite of unchanged insulin, providing sufficient evidence that the pancreatic α cell is under the tonic inhibitory control of GLP‐1 in humans.12 Moreover, ex(9‐39)NH2 completely prevented the decrease in plasma glucagon occurring with intestinal glucose, suggesting glucose induced suppression of glucagon being largely mediated by GLP‐1. Clearly, glucagon suppression during the high duodenal glucose load was abolished by the GLP‐1 antagonist while significantly raising plasma GLP‐1. This demonstrates that endogenous GLP‐1 not only tonically suppresses fasting glucagon but further mediates postprandial glucagon inhibition.

Duodenal glucose at 1 kcal/min (1 kcal/ml) did not raise plasma GLP‐1, as previously described.14 However, release of GLP‐1 by duodenal glucose approximating its secretory threshold may depend on both concentration and flow rate: the same caloric load at 0.33 kcal/ml and 3 ml/min was shown to induce a modest increase in GLP‐1.39 A higher duodenal flow rate may overrun the duodenal capacity of glucose absorption, which is up to 1.4 kcal/min.40 Independent of the ongoing discussion of a neurohumoral pathway triggering GLP‐1 release from the lower intestine in humans, this may point to the jejunum as a source of GLP‐1, at least under the experimental conditions of direct duodenal glucose perfusion. During ex(9‐39)NH2, plasma GLP‐1 was markedly increased, not during fasting but during duodenal glucose stimulation. In contrast, ex(9‐39)NH2 simultaneously infused with synthetic GLP‐1 did not augment GLP‐1 plasma levels compared with intravenous GLP‐1 alone.12 This argues against an interaction of ex(9‐39)NH2 with metabolism of GLP‐1. We therefore suggest autofeedback inhibition of GLP‐1, which is interrupted by the GLP‐1 receptor antagonist. This hypothesis is supported by studies employing the GLP‐1 agonist exendin‐4, thereby reducing plasma levels of endogenously released GLP‐1.41 How this putative feedback is regulated in detail remains to be established.

The third key action of synthetic GLP‐1 reducing acute glycaemia is retardation of gastric emptying. This raises the question of whether GLP‐1 is an enterogastrone (that is, a gut hormone which mediates feedback inhibition of upper gastrointestinal motility and/or secretion after intestinal nutrient exposure). Known motor actions of synthetic GLP‐1 include relaxation of the proximal stomach, inhibition of antroduodenal contractility, and stimulation of pyloric motility, with the latter serving as a brake to gastric emptying.5,6,42 This postprandial pattern of antro‐pyloro‐duodenal motility occurs in a similar way after oral meal intake14,18,43 and was dose dependently mimicked by duodenal glucose perfusion.

Even during fasting ex(9‐39)NH2 markedly stimulated antral and duodenal motility, leading to the occurrence of aborally propagated phase IIIs in most volunteers. This clearly indicates that fasting antroduodenal motility is tonically suppressed by GLP‐1. Moreover, postprandially released GLP‐1 contributes to inhibition of antroduodenal motility induced by intestinal carbohydrates. In terms of the pylorus, ex(9‐39)NH2 attenuated stimulation of both its tonic and phasic motility to low duodenal glucose, and completely abolished the further increase in pyloric tone occurring with the high duodenal glucose load. Thus GLP‐1 largely mediates pyloric stimulation triggered by duodenal carbohydrates. As the response of antro‐pyloro‐duodenal motility to intestinal carbohydrates is significantly modulated by GLP‐1, we suggest the peptide hormone as an enterogastrone in humans. However, the GLP‐1 antagonist was unable to completely reverse the effects induced by intraduodenal glucose. Some degree of small intestinal feedback inhibition may still have been operative. The feedback pathways mediating antral and pyloric motor response are as yet poorly understood. In humans, the pyloric motor response to intraduodenal glucose involves muscarinergic stimulation.21 The impact of intestinal hormones other than GLP‐1 released by carbohydrates is largely unknown. GIP has no effect on gastric emptying,44 and PYY may inhibit gastric emptying but its effects on motility are unclear.45 On the other hand, acute hyperglycaemia is well known to dose dependently slow gastric emptying, to inhibit antral motility, and to stimulate pyloric motility.9 As the effects of hyperglycaemia on gastric emptying and antral motility occur within the normal range of postprandial glycaemia, the modest elevation in blood glucose during duodenal glucose may have superimposed the motility effects of the GLP‐1 antagonist.

The precise mechanism for GLP‐1 stimulating pyloric and inhibiting antral motility is not entirely clear. Animal studies indicated no direct effect of GLP‐1 on gastric smooth muscle cells.46,47 Multiple findings support the notion that suppression of vagal neural input is involved in the inhibition of gastric motor functions by exogenous GLP‐1.3,4,48 GLP‐1 may interact with vagal afferent nerves49 or may affect specific GLP‐1 binding sites in the area postrema accessible to GLP‐1 from the systemic circulation.50,51 However, as the pylorus is stimulated by vagal cholinergic activity, its stimulation by GLP‐1 may not be mediated by cholinergic inhibition. Further studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms which mediate gastric motor effects induced by GLP‐1.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that endogenous GLP‐1 plays an important role in the fasting and postprandial regulation of endocrine pancreatic secretion and of antro‐pyloro‐duodenal motility in humans. As an incretin hormone, GLP‐1 glucose dependently stimulates insulin secretion. It tonically suppresses glucagon release and lowers postprandial glucagon excursions. As enterogastrone, it inhibits antral and stimulates pyloric motility, both of which may contribute to inhibition of gastric emptying.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Michaela Junck, Gabriele Kraft, and Elisabeth Bothe for expert technical assistance. This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, grant No AR 149/1‐2, and the German Diabetes Society (DDG).

Abbreviations

ex(9‐39)NH2 - exendin(9‐39)amide

GLP‐1 - glucagon‐like peptide 1

GIP - glucose dependent insulinotropic polypeptide

IPPW - isolated pyloric pressure waves

SR - secretory response

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kreymann B, Williams G, Ghatei M A.et al Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 7‐36: a physiological incretin in man. Lancet 198721300–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komatsu R, Matsuyama T, Namba M.et al Glucagonostatic and insulinotropic action of glucagonlike peptide I‐(7‐36)‐amide. Diabetes 198938902–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schirra J, Leicht P, Hildebrand P.et al Mechanisms of the antidiabetic action of subcutaneous glucagon‐like peptide‐1(7‐36)amide in non‐insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Endocrinol 1998156177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schirra J, Kuwert P, Wank U.et al Differential effects of subcutaneous GLP‐1 on gastric emptying, antroduodenal motility, and pancreatic function in men. Proc Assoc Am Physicians 199710984–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schirra J, Wank U, Arnold R.et al Effects of glucagon‐like peptide‐1(7‐36)amide on motility and sensation of the proximal stomach in humans. Gut 200250341–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schirra J, Houck P, Wank U.et al Effects of glucagon‐like peptide‐1(7‐36)amide on antro‐pyloro‐duodenal motility in the interdigestive state and with duodenal lipid perfusion in humans. Gut 200046622–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wettergren A, Schjoldager B, Mortensen P E.et al Truncated GLP‐1 (proglucagon 78–107‐amide) inhibits gastric and pancreatic functions in man. Dig Dis Sci 199338665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nauck M A, Niedereichholz U, Ettler R.et al Glucagon‐like peptide 1 inhibition of gastric emptying outweighs its insulinotropic effects in healthy humans. Am J Physiol 1997273E981–E988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rayner C K, Samsom M, Jones K L.et al Relationships of upper gastrointestinal motor and sensory function with glycemic control. Diabetes Care 200124371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolligs F, Fehmann H C, Goke R.et al Reduction of the incretin effect in rats by the glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor antagonist exendin (9–39) amide. Diabetes 19954416–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Wang R M, Owji A A.et al Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 is a physiological incretin in rat. J Clin Invest 199595417–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schirra J, Sturm K, Leicht P.et al Exendin(9‐39)amide is an antagonist of glucagon‐like peptide‐1(7‐36)amide in humans. J Clin Invest 19981011421–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards C M, Todd J F, Mahmoudi M.et al Glucagon‐like peptide 1 has a physiological role in the control of postprandial glucose in humans: studies with the antagonist exendin 9–39. Diabetes 19994886–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schirra J, Katschinski M, Weidmann C.et al Gastric emptying and release of incretin hormones after glucose ingestion in humans. J Clin Invest 19969792–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeFronzo R A, Tobin J D, Andres R. Glucose clamp technique: a method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol 1979237E214–E223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nauck M A, Homberger E, Siegel E G.et al Incretin effects of increasing glucose loads in man calculated from venous insulin and C‐peptide responses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 198663492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katschinski M, Dahmen G, Reinshagen M.et al Cephalic stimulation of gastrointestinal secretory and motor responses in humans. Gastroenterology 1992103383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heddle R, Fone D, Dent J.et al Stimulation of pyloric motility by intraduodenal dextrose in normal subjects. Gut 1988291349–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nauck M, Stockmann F, Ebert R.et al Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non‐insulin‐dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia 19862946–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vilsboll T, Krarup T, Deacon C F.et al Reduced postprandial concentrations of intact biologically active glucagon‐like peptide 1 in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 200150609–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fone D R, Horowitz M, Dent J.et al Pyloric motor response to intraduodenal dextrose involves muscarinic mechanisms. Gastroenterology 19899783–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houghton L A, Read N W, Heddle R.et al Relationship of the motor activity of the antrum, pylorus, and duodenum to gastric emptying of a solid‐liquid mixed meal. Gastroenterology 1988941285–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perley M J, Kipnis D M. Plasma insulin responses to oral and intravenous glucose: studies in normal and diabetic sujbjects. J Clin Invest 1967461954–1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nauck M A, Homberger E, Siegel E G.et al Incretin effects of increasing glucose loads in man calculated from venous insulin and C‐peptide responses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 198663492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nauck M, Stockmann F, Ebert R.et al Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non‐insulin‐dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia 19862946–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nauck M A, Homberger E, Siegel E G.et al Incretin effects of increasing glucose loads in man calculated from venous insulin and C‐peptide responses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 198663492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nauck M, Stockmann F, Ebert R.et al Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non‐insulin‐dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia 19862946–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nauck M A, Homberger E, Siegel E G.et al Incretin effects of increasing glucose loads in man calculated from venous insulin and C‐peptide responses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 198663492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tillil H, Shapiro E T, Miller M A.et al Dose‐dependent effects of oral and intravenous glucose on insulin secretion and clearance in normal humans. Am J Physiol 1988254E349–E357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ebert R, Creutzfeldt W. Influence of gastric inhibitory polypeptide antiserum on glucose‐induced insulin secretion in rats. Endocrinology 19821111601–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ebert R, Unger H, Creutzfeldt W. Preservation of incretin activity after removal of gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) from rat gut extracts by immunoadsorption. Diabetologia 198324449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lauritsen K B, Moody A J, Christensen K C.et al Gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) and insulin release after small‐bowel resection in man. Scand J Gastroenterol 198015833–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tseng C C, Kieffer T J, Jarboe L A.et al Postprandial stimulation of insulin release by glucose‐dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). Effect of a specific glucose‐dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor antagonist in the rat. J Clin Invest 1996982440–2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elahi D, McAloon‐Dyke M, Fukagawa N K.et al The insulinotropic actions of glucose‐dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (7–37) in normal and diabetic subjects. Regul Pept 19945163–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nauck M A, Bartels E, Orskov C.et al Additive insulinotropic effects of exogenous synthetic human gastric inhibitory polypeptide and glucagon‐like peptide‐1‐(7–36) amide infused at near‐physiological insulinotropic hormone and glucose concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 199376912–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fehmann H C, Hering B J, Wolf M J.et al The effects of glucagon‐like peptide‐I (GLP‐I) on hormone secretion from isolated human pancreatic islets. Pancreas 199511196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heller R S, Aponte G W. Intra‐islet regulation of hormone secretion by glucagon‐like peptide‐1‐(7–36) amide. Am J Physiol 1995269G852–G860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmid R, Schusdziarra V, Aulehner R.et al Comparison of GLP‐1 (7‐36amide) and GIP on release of somatostatin‐like immunoreactivity and insulin from the isolated rat pancreas. Z Gastroenterol 199028280–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Donovan D G, Doran S, Feinle‐Bisset C.et al Effect of variations in small intestinal glucose delivery on plasma glucose, insulin, and incretin hormones in healthy subjects and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004893431–3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfeiffer A, Schmidt T, Vidon N.et al Effect of ethanol on absorption of a nutrient solution in the upper human intestine. Scand J Gastroenterol 199328515–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards C M, Stanley S A, Davis R.et al Exendin‐4 reduces fasting and postprandial glucose and decreases energy intake in healthy volunteers. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2001281E155–E161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anvari M, Paterson C A, Daniel E E.et al Effects of GLP‐1 on gastric emptying, antropyloric motility, and transpyloric flow in response to a nonnutrient liquid. Dig Dis Sci 1998431133–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Houghton L A, Read N W, Heddle R.et al Motor activity of the gastric antrum, pylorus, and duodenum under fasted conditions and after a liquid meal. Gastroenterology 1988941276–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meier J J, Goetze O, Anstipp J.et al Gastric inhibitory polypeptide does not inhibit gastric emptying in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2004286E621–E625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Savage A P, Adrian T E, Carolan G.et al Effects of peptide YY (PYY) on mouth to caecum intestinal transit time and on the rate of gastric emptying in healthy volunteers. Gut 198728166–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodier G, Magous R, Mochizuki T.et al Effect of glicentin, oxyntomodulin and related peptides on isolated gastric smooth muscle cells. Pflugers Arch 1997434729–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tolessa T, Gutniak M, Holst J J.et al Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 retards gastric emptying and small bowel transit in the rat: effect mediated through central or enteric nervous mechanisms. Dig Dis Sci 1998432284–2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wettergren A, Wojdemann M, Holst J J. Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 inhibits gastropancreatic function by inhibiting central parasympathetic outflow. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 1998275G984–G992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imeryuz N, Yegen B C, Bozkurt A.et al Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 inhibits gastric emptying via vagal afferent‐mediated central mechanisms. Am J Physiol 1997273G920–G927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Orskov C, Poulsen S S, Moller M.et al Glucagon‐like peptide I receptors in the subfornical organ and the area postrema are accessible to circulating glucagon‐like peptide I. Diabetes 199645832–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goke R, Larsen P J, Mikkelsen J D.et al Distribution of GLP‐1 binding sites in the rat brain: evidence that exendin‐4 is a ligand of brain GLP‐1 binding sites. Eur J Neurosci 199572294–2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]