Abstract

Background

Previous studies of anticipation in familial pancreatic cancer have been small and subject to ascertainment bias. Our aim was to determine evidence for anticipation in a large number of European families.

Patients and methods

A total of 1223 individuals at risk from 106 families (264 affected individuals) were investigated. Generation G3 was defined as the latest generation that included any individual aged over 39 years; preceding generations were then defined as G2 and G1.

Results

With 80 affected child‐parent pairs, the children died a median (interquartile range) of 10 (7, 14) years earlier. The median (interquartile range) age of death from pancreatic cancer was 70 (59, 77), 64 (57, 69), and 49 (44, 56) years for G1, G2, and G3, respectively. These indications of anticipation could be the result of bias. Truncation of Kaplan‐Meier analysis to a 60 year period to correct for follow up time bias and a matched test statistic indicated significant anticipation (p = 0.002 and p<0.001). To minimise bias further, an iterative analysis to predict cancer numbers was developed. No single risk category could be applied that accurately predicted cancer cases in every generation. Using three risk categories (low with no pancreatic cancer in earlier generations, high with a single earlier generation, and very high where two preceding generations were affected), incidence was estimated without significant error. Anticipation was independent of smoking.

Conclusion

This study provides the first strong evidence for anticipation in familial pancreatic cancer and must be considered in genetic counselling and the commencement of secondary screening for pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: familial pancreatic cancer, anticipation, screening, epidemiology, DNA repair

Approximately 5% of pancreatic cancers are inherited,1,2,3,4 in some instances associated with a general familial cancer syndrome such as familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome, familial adenomatous polyposis, hereditary non‐polyposis colorectal cancer, hereditary breast‐ovarian cancer syndrome, and Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome.5,6,7,8,9 Familial pancreatic cancer is a rare syndrome with an apparent autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, although the main gene or genes responsible have not yet been identified.2,3,10 Germline BRCA2 mutations may occur in up to 20% of familial pancreatic cancer families3,11 and the chromosomal locus 4q32‐34 has been associated with one family.12

Genetic anticipation refers to the earlier age of onset of familial diseases in successive generations. Anticipation was originally identified in some inherited neurological diseases13,14 and then in certain diseases with a non‐mendelian pattern of inheritance.15,16,17,18,19 Anticipation is well established in familial leukaemias20,21,22 and lymphomas23,24,25 and may also occur in solid tumours.26 It is important to determine if anticipation is seen in familial pancreatic cancer because this will provide clues as to the nature of the disease gene and facilitate prediction of the age of cancer onset for an individual. This will assist in estimating whether an unaffected individual is a carrier, which is vital for linkage analysis, and will be important for determining the most appropriate age at which to commence secondary screening for pancreatic cancer.27,28

Evidence for anticipation in familial pancreatic cancer has not been adequately tested.29,30 One of the difficulties with assessing genetic anticipation is ascertainment bias.31,32 With late onset diseases, particularly where the disease gene is unknown, a retrospective study will show apparent anticipation because individuals in later generations who may go on to develop the disease relatively late will appear to be unaffected.15,33 These kinds of data are also hierarchical in structure due to the nesting of affected patients within families and hence are not completely independent.31,34 Ascertainment bias may be reduced by increasing the number of families studied and by applying relatively new statistical methodology to minimise biases.31,34,35,36 This study of 106 European families has employed standard analytical techniques as well as adopting a novel iterative approach to minimise biases in the analysis of anticipation.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Subjects were recruited by the European Registry of Hereditary Pancreatitis and Familial Pancreatic Cancer (EUROPAC)34 and the German National Case Collection for Familial Pancreas Cancer (FaPaCa).29 Following informed consent the probands completed family and personal health questionnaires. Patients' clinicians also completed parallel questionnaires which were used for confirmation of clinical details, and hospital and pathology notes were also obtained. Clinics were arranged and family members were invited to attend via the proband.

Individuals were classified as affected based on histological confirmation of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma where available. Where histology was not available good quality medical notes or reliable cancer registry information were used, in all cases copies of reports or notes were considered by at least two members of the study (for EUROPAC CDM or NH and WG). Familial pancreatic cancer was defined as families with two or more affected individuals not fulfilling criteria for any other familial cancer syndrome. Previously described familial pancreatic cancer families with a germline BRCA2 mutation identified were excluded from this analysis in order to reduce genetic heterogeneity.11 Too few cases of pancreatic cancer are available in these BRCA2 families or families from other cancer syndromes for meaningful subgroup analysis.

Statistical analyses

Age was expressed as median (interquartile range). Improvement in diagnosis could give the impression of anticipation if event time was taken as age of diagnosis while improvements in treatment would reduce apparent anticipation if event time was taken as age of death; to be conservative in our evaluation of anticipation, event time was taken as age of death from pancreatic cancer. Affected parent‐affected child pairs were analysed with the paired t test. Individuals were assigned to one of three generations (G1, G2, and G3) depending on their position within the family tree and the matched version of the anticipation test described by Hsu et al employed.35 G3 was the latest generation that included any individual at significant risk of cancer (defined as any individual aged over 39 years) and preceding generations were then defined as G2 and G1. Earlier and later generations were not classified (fig 1). For comparison, affected individuals were also compared by three year of birth cohorts (1900–1919, 1920–1939 and 1940–69); individuals were excluded from this analysis where the precise date of birth was unknown despite the age having been stated. Survival from birth until death from pancreatic cancer was analysed by the Kaplan‐Meier method and compared by log rank analysis. Survival analysis was also undertaken by truncation to an equal 60 year observation period for all individuals to correct for follow up time bias.36 All at risk individuals were included from the families, with data censored at present age or age of death from causes other than pancreatic cancer. Because all of the aforementioned methods have an inherent bias, a novel iterative approach was also developed. This involved multiplication of the chance an individual is a carrier of the disease gene by an age related measure of penetrance and establishing that this would only reflect the observed incidence of cancer assuming that the age related penetrance increases with successive generations; this will be described in more detail later. To test the influence of smoking, individuals were divided into those who had ever smoked (ex‐ and present smokers) and those who had never smoked. Smoking data were analysed using survival analysis as well as the χ2 and Fisher's exact probability tests. The statistical package used was StatView Version 5 and significance was set at p<0.05.

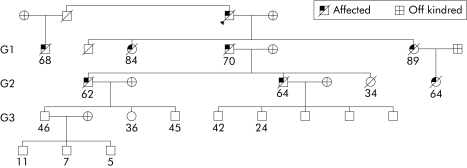

Figure 1 A typical familial pancreatic cancer family tree. This is a family with eight affected individuals, showing their ages at death or last contact. The generations within the family were defined on the basis that generation 3 (G3) was the first generation with any individual aged over 39 years and G2 and G1 were defined from this.

Ethics

The study was approved by the North West Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (UK); MREC 03/8/069. Local research ethics committees approval was obtained in participating centres.

Results

Description of families

At the time of guillotine, 106 families had been recruited with multiple cases of pancreatic cancer, no BRCA2 mutation, and a family tree that was complete over the range of individuals to be analysed (not necessarily including siblings of the earliest individuals in each kindred). Of these families, 88 had only pancreatic cancer, 10 had pancreatic (at least two cases within the family) and gastric cancers (there were 21 cases of gastric cancer in total), and the remaining eight families had pancreatic cancer (at least two cases) in association with other malignancies. In 52 families histological confirmation of pancreatic cancers was possible in at least one case; in the remainder good quality medical notes or reliable cancer registry information was used. A typical family tree is shown in fig 1.

Description of affected individuals

There were a total of 1223 individuals at risk and 264 individuals with pancreatic cancer. Pancreatic resection is only normally undertaken in 2.6–9% of patients as a result of a high incidence of locally advanced and metastatic disease at presentation.37,38,39,40 Despite this, histological confirmation was possible in 57 (22%) affected individuals; good quality medical notes or reliable cancer registry information was used for all others. At least two affected individuals in each family were first degree relatives.

Other diseases

We observed 22 cases of diabetes; 16 cases in as yet unaffected and six in affected individuals. There were 10 cases of acute pancreatitis (three in patients who later developed pancreatic cancer) and two cases of chronic pancreatitis in as yet unaffected individuals. In addition to cases of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and gastric cancer there were three basal cell carcinomas, two brain tumours, four cervical cancers, 11 colorectal cancers, one duodenal cancer, two cholangiocarcinomas, one pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma, one pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour, and 17 cancers with unknown primary. Although it is possible that the other cancers and pancreatic diseases are surrogate markers for gene carriers, the numbers are too small to make any definitive conclusions, and for the purposes of anticipation analysis, these individuals were considered to be unaffected.

Smoking

In 84 families where smoking data were available, analysis did not reveal a statistically significant difference between smoking habit in affected and non‐affected individuals (Fisher's exact test p = 0.44). Neither did we establish that smoking affected survival using a Kaplan‐Meier analysis (log rank χ21 = 0.44, p = 0.5; n = 125 smokers and 79 non‐smokers). Smoking is discussed later in relation to anticipation.

Standard analyses for anticipation

Median (interquartile range) age of death from pancreatic cancer was 62 (53, 70) years and was lower than expected.41 Median age was 65 (57, 71) years for 138 women compared with 59 (49, 67) years for 126 men, but this sex difference was not significant by survival analysis (log rank χ21 = 2.6, p = 0.27). Children died a median of 10 years earlier than their parents among the 80 child‐parent affected pairs identified (p<0.001, paired t test) (table 1). Later generations had an earlier age of death from pancreatic cancer than individuals from preceding generations and a similar effect was observed in the analysis of birth cohorts (both p<0.001) (table 2). There was a degree of correspondence between the birth cohorts and generations and so some of the effect may be because of genuine differences between generations (fig 2).

Table 1 Differences in age of death of paired affected parents and affected children.

| Affected child‐affected parent pairing | No of pairs | Difference in age of death (mean (95% CI)) | p Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| All child‐parent pairings | 80 | −10.7 (−13.9, −7.6) | <0.001 |

| Son‐father | 21 | −4 (−9.4, 1.4) | 0.21 |

| Son‐mother | 18 | −17.7 (−23.4, −12.0) | <0.001 |

| Daughter‐father | 18 | −8.4 (−16.7, −0.2) | 0.06 |

| Daughter‐mother | 23 | −13.4 (−18.1, −8.6) | <0.001 |

*Paired t test.

There were 80 pairs consisting of a parent and child who have died of pancreatic cancer. The differences in age of death are given with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Children died at an earlier age than their parents, this was statistically significant but may be explained by bias. Thus more stringent testing of anticipation was applied.

Table 2 Apparent anticipation with successive generations based on analysis of succeeding generations and cohorts by year of birth.

| Generation | n | Age of death (y)* | Cohort | Date of birth | n | Age of death (y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 50 | 70 (59, 77) | C1 | 1900–19 | 53 | 70 (61, 76) |

| G2 | 158 | 64 (57, 69) | C2 | 1920–39 | 136 | 64 (57, 69) |

| G3 | 53 | 49 (44, 56) | C3 | 1940–69 | 62 | 50 (46, 55) |

*Values are median (interquartile range).

Affected individuals were grouped according to generation (see text) or by date of birth.

All differences were significant: Kruskal‐Wallis p<0.001 for generations and cohorts; Mann‐Whitney U, p<0.001 for G1 versus G2, G2 versus G3, and G1 versus G3, and C1 versus C2, C2 versus C1, and C1 versus C3. This clearly could be due to bias of ascertainment and truncation effects of age at death in G2 and G3 compared with G1.

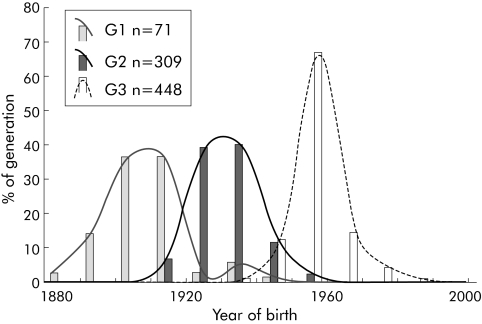

Figure 2 Distribution of all individuals in the three generations (G1, G2, and G3) based on year of birth. Median year of birth (interquartile range) of G1 = 1909 (1903, 1914), G2 = 1930 (1925, 1936), and G3 = 1950 (1950, 1957) years.

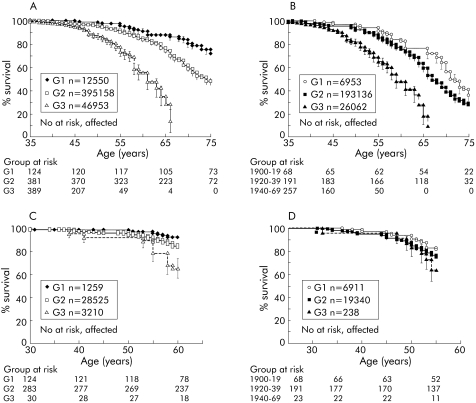

Kaplan‐Meier analysis showed that cumulative deaths from pancreatic cancer for all at risk individuals by 77 years was 50%; as only 50% of the kindred would be predicted to carry the gene, this implies 100% lifetime risk for gene carriers. As cumulative survival actually falls below 50% beyond 77 years, there must be an element of ascertainment bias in this analysis, which becomes apparent as the number of at risk individuals declines; but in support of autosomal dominance, and high penetrance, 25% cumulative incidence of pancreatic cancer in at risk individuals (event time 65 years) compares well with 50% cumulative survival for the subgroup of individuals who develop pancreatic cancer (event time 62 years). Analysis of all individuals from each family showed a reduction in survival of later generations compared with their ancestors (log rank χ22 = 74.21, p<0.001) (fig 3A). Median (95% confidence interval) age at which 50% of family members in G1, G2, and G3 were affected was 87 (85, 89), 74 (72, 76), and 61 (59, 63) years, respectively. A similar effect was observed using birth cohorts (log rank χ22 = 40.42, p<0.001) (fig 3B).

Figure 3 Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis of individuals from different generations and date of birth based cohorts. The numbers below the graphs show the number of family members from each group at each time point who were considered in the survival analysis. (A) Age of death of individuals was significantly different between generations G1, G2, and G3 (989 at risk, 261 affected; log rank χ22 = 74.21, p<0.001). (B) Age of death of individuals was significantly different between date of birth based cohorts (522 at risk, 251 affected; log rank χ22 = 40.42, p<0.001). (C) Age of death of individuals with an observation period restricted to 60 years (all born before 1943) was significantly different between generations G1, G2, and G3 (442 at risk, 44 affected; log rank χ22 = 16.93, p = 0.002). (D) Age of death of individuals with an observation period restricted to 60 years (all born before 1943) was not significantly different between the three birth cohorts (285 at risk, 59 affected; log rank χ22 = 2.72, p = 0.6).

Birth cohort 1900–1919 included all relatives who by 2004 would be aged 85–94 years, the 1920–39 cohort would have individuals aged 65–74 years, but the 1940–69 cohort only had individuals aged 35–64 years. Any analyses based on these observed data will necessarily miss the events that would occur in the next 20 years, resulting in apparent anticipation. Although there is overlap between the dates of birth of G1, G2, and G3 populations (fig 2), a similar bias exists for generations.

Truncation analysis on a subset of individuals who had been observed for an equal 60 year period (individuals born up to the year 1943), also showed a significant difference between the groups defined by generation (log rank χ22 = 16.93, p = 0.002) (fig 3C) but not for the birth cohorts (log rank χ22 = 2.72, p = 0.6) (fig 3D). This is an improvement on the Kaplan‐Meier analysis described above but is still subject to ascertainment bias; the small number of cancer cases in G3 may reflect unusual cases while the majority of G3 individuals who are not affected are not taken into consideration. To allow for this we used the matched test statistic of Hsu and colleagues.35 This scores individuals (affected or unaffected) according to consistency with anticipation. Differences between G1 and G2 and G2 and G3 were both significant (p<0.001). However, this does not take into account the likelihood that an individual is a gene carrier (and so at high risk). Later generations have a higher ratio of unaffected carriers to non‐carriers, potentially giving bias.

A novel iterative approach to test for anticipation

If there is no generation effect (for example, anticipation) on the age of death from pancreatic cancer, the age related penetrance function for carriers from one generation could be used to predict the number of pancreatic cancer cases seen in any other generation (regardless of the period of observation). Individual pancreatic cancer risk (pi) for each individual (i) can be calculated by multiplying the probability of an individual being a gene carrier by the respective age related penetrance to time of observation. For any generation within a family there will be a number of possible configurations of diagnoses. For each configuration, all individuals (regardless of their actual diagnosis) are assigned a state (cancer or non‐cancer); hence for N individuals there will be 2N configurations. The probability of each individual having the defined state is either pi (cancer) or 1−pi (no cancer). The probability (cg) of obtaining a configuration can be calculated by multiplying all of the individual probabilities within that generation. Thus the probability for observing n cancer cases in a generation would be the sum of all cg for a configuration, giving n cases.

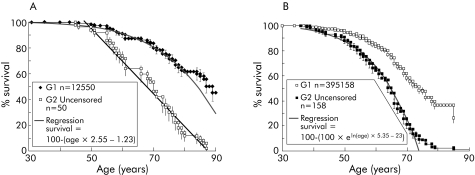

Only the G1generation has been followed up sufficiently to allow a realistic estimation of age related penetrance. Survival of affected individuals (uncensored data) in the G1 cohort appeared to decline from the age of 50 years with a linear gradient of 0.0255 (fig 4A). This is just a description of what has happened in the past to this particular group and provides one of many possible measures of age related penetrance; the specific function is not crucial in the following arguments. This measure of age related penetrance would be predicted to be an overestimate, as it does not take into account any individuals who would have later developed pancreatic cancer but died from other causes. The parent, sibling, or offspring of an affected person has a 50% chance of being a carrier (in this analysis no consideration was given to the disease status of the subject, just of their relatives). A second degree relative has a 25% chance and so on.

Figure 4 Actual survival data compared with estimates based on age related penetrance. (A) For the purposes of estimating age related penetrance, it was assumed that a carrier had no risk of cancer until the age of 55 years and from then to the age of 90 years the risk increased linearly: 1−([age×0.0255]−1.2). This is empirically based on the survival (birth to death) data curve and is not based on any assumed biological model or on literature sources. It is not assumed to have any merit other than as a tool to estimate age dependent risk. After the age of 90 years a carrier was assumed to have a risk of 1 (100% chance of being affected). For comparison, a regression is also shown using data from both censored (as yet unaffected) and uncensored (affected) individuals. (B) Curve used to derive another empirical formula with a greater age related risk, based on uncensored data from G2 (see table 3).

The probability of an individual being affected in G1 (calculated by multiplying the carrier probability with the risk defined just for uncensored individuals) was found to be a slight overestimate (0.65 v 0.63 cases observed per family). This did not represent a significant difference (two sided p value, p = 0.37) and suggested that simple regression analysis was adequate; clearly other formulae estimating age related risk could be found that would also work. Even assuming 100% lifetime penetrance, prediction of the number of affected individuals in subsequent generations would tend to be an overestimate—assuming risk does not increase with generation—as in G1 we have a higher ratio of affected to unaffected individuals than in other generations. In fact, the same analysis for G2 showed that there was an underestimate of the number of affected individuals (0.8 v 1.5 cases observed per family in G2).

The difference between the calculated and observed incidence of cancer in the different generations was significant for G2 and G3 but not G1 (table 3). This means that this measure of age related penetrance is effective for G1 and in order to be applicable to G2 and G3 the function would have to be changed to give a greater risk. Thus the risk of cancer death in later generations was genuinely higher than in earlier generations.

Table 3 Results of simulation.

| Equation used to calculate estimate (E) | G1 (80 families)* | G2 (106 families)* | G3 (101 families)* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | E | p | O | E | p | O | E | p | |

| Low risk | 0.65 | 0.374 | 1.52 | 0.82 | <10−6 | 0.5 | 0.09 | <10−6 | |

| E = ∑Pr (1−((age×0.03)−1.2) | |||||||||

| (for age = 55–90) + ∑Pr (for over 90) | |||||||||

| High risk | 0.63 | 1.14 | 0.003 | 1.52 | 1.32 | 0.417 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 0.028 |

| E = ∑Pr (1–eln (age)×5.35–23) | |||||||||

| (for age = 40–75) + ∑Pr (for over 75) | |||||||||

*Some families could not be included because of unreliable data on ages.

On average, there were six observed affected individuals in generation 1 (G1) from every 10 families, 15 from G2, and five from G3. Two classes of risk were estimated (low and high) based on age and probability of being a carrier (Pr). This was used to estimate the number of affected individuals in each generation (E) E was compared with the observed number of affected individuals per family (O). Two sided p values of less than 0.01 were taken to indicate that the estimated values were not consistent with observed values. A risk calculation giving expected cases equivalent with observed values in G2 would overestimate expected values in G1 and underestimate in G3. Clearly, a still greater risk could be assumed that would give a better estimate of G3 cancer incidence. This implies that age related risk increased with each generation.

To refine the test of anticipation, a second level of risk was produced for generations other than G1. Regression analysis to provide the best fit to the survival curve for G2 (fig 4B) was 1−eln (age)×5.35–23. The whole population was then modelled assuming a risk defined as the chance of being a carrier multiplied by 1−eln (age)×5.35–23 (table 3). The difference between expected and observed cancer incidence in G3 is indicative of a further increase in risk for the third generation but evidence for this is less conclusive. This analysis indicated at least two risk categories: low where there is no earlier generation with pancreatic cancer, high where there is a single earlier generation, and perhaps a still higher risk group where two preceding generations are affected.

Smoking and anticipation

To test if an increase in smoking habit might explain anticipation, we compared the smoking habit of individuals from the different generations. Later generations smoked less than earlier generations (table 4) but this difference was not significant (χ22 = 5.13, p = 0.08) and could possibly also be explained by bias. Smoking data were only available for 64 affected individuals and the patient provided this information directly in only eight cases; in the other 56 cases, information was provided by spouses, children, and in four cases by grandchildren. It is easier to be confident that a relative is a smoker than to be confident that a relative has never smoked. As we censored out all responses that were not confident, there is a predicted bias for defining affected individuals as smokers. Five of the self reporting affected individuals were in G2; the remaining three were in G1. Four (50%) of the self reporters defined themselves as non‐smokers while only 10 (18%) of the remaining affected individuals were defined by relatives as non‐smokers.

Table 4 Smoking did not appear to be a confounding factor leading to anticipation.

| Cohort | Total | Non‐smokers | Current or ex‐smokers | % Smokers (of generation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affected | Censored | Affected | Censored | Affected | Censored | ||

| All generations | 211 | 22 | 59 | 42 | 88 | 66 | 60 |

| G1 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 80 | 100 |

| G2 | 71 | 11 | 12 | 24 | 24 | 69 | 67 |

| G3 | 127 | 9 | 47 | 10 | 61 | 53 | 56 |

Only adults older than 16 years of age and those defined within generations (G1, G2, or G3) were included. A higher number of both affected and unaffected (censored) individuals used tobacco in earlier generations than in later generations but this was not significant (χ22 = 5.13, p = 0.08). None of the comparisons was statistically significant, either in comparisons of generations (log rank χ21 = 0.44, p = 0.5) or comparisons of smoking with affected status (Fisher's exact probability test p = 0.44).

Discussion

This study has clearly demonstrated the phenomenon of anticipation in familial pancreatic cancer using analytical techniques to minimise statistical artefact. Anticipation for the development of pancreatic cancer was approximately six years between the oldest and intermediate generation. This compares with 22 years in nine of 28 families in a previous study.30

Anticipation observed could be the result of environmental factors; the statistical methods used here do not exclude participation of environmental factors or the existence of competing causes for death in older generations. Only smoking habit has ever convincingly been associated with pancreatic cancer risk in both sporadic and familial pancreatic cancer.1,30,42,43,44 Although in our study there was no significant association between smoking and cancer, this could reflect a limitation of the data rather than evidence that smoking does not influence cancer onset in these families. Nevertheless, the decline in smoking habit, which was observed with later generations, would act against anticipation and not in favour. In order for smoking to account for anticipation, this trend would need not only to be artefactual but would have to be reversed. Non‐response bias due to greater reliance on second person reporting for earlier generations could give a trend to less smoking habit in later generations but the trend is consistent with much larger and less biased studies carried out on the general population.45 Therefore, the only environmental factor established as being an influence on pancreatic cancer onset is unlikely to explain anticipation.

Genetic anticipation should be family specific so the progress of individuals in one family towards an earlier onset should not be relevant to the progression in another family, unless there is a common founder in a recent generation. A recent common founder is unlikely in this study given the geographical diversity of the families. Population based anticipation could be genetic if the number of generations over which pancreatic cancer is penetrant is limited; for example, an apparent founder, their children, and grandchildren. By definition, any founder in generation three (G3) would not be included in the study, as a family can only be recruited on the basis of multiple cases of pancreatic cancer. Similarly, no third generation affected individuals (grandchildren) can be included in G1 as no subsequent generation would have contained affected individuals. Although this would still allow for some misclassification, it would mean that the definition of the generations would have some biological validity. Anticipation and generation limitation have been reported in Li‐Fraumeni syndrome, where in more than 90% of families studied cancer penetrance is limited to three generations46; limitation can be explained by carriers dying before reaching childbearing age, clearly not the case with pancreatic cancer patients in our study.

Some inherited neurological diseases demonstrating anticipation13,14 have been linked to genes with trinucleotide repeat expansions becoming increasingly unstable in successive generations.33,47,48 The situation in cancer syndromes may be more complex18,33 and anticipation may be related to epigenetic factors.49 In hereditary breast cancer, BRCA2 mutation carriers have a greater degree of anticipation than those without known mutations.50,51 Mutations of the BRCA2 gene impair recombinational DNA repair; this may be relevant to familial pancreatic cancer families with BRCA2 mutations.11 Anticipation has also been reported in hereditary non‐polyposis colorectal cancer caused by mutations in mismatch repair genes.31

Anticipation in this study may be due to a DNA repair gene other than BRCA2. This could account for a limitation in the number of generations with penetrant pancreatic cancer. The mutation in itself could be inadequate to result in an elevated cancer risk but heterozygotes may accumulate other mutations in their germline. A steady level of genetic damage will be maintained by segregation of unlinked mutations with the disease allele augmented by further mutations resulting from repair deficiency. However, some new mutations will be linked to the disease gene and so the level of genetic damage overall will increase in carriers. A point may be reached (for example, G1) where genetic damage weakens cell cycle regulation resulting in cancer. Further accumulation of damage would result in earlier development of cancer in successive generations (hence anticipation). Eventually (for example, following G3), accumulation of defects prevents subsequent incidence of pancreatic cancer (for example, prevents gametogenesis, is fatal in utero, or results in an individual who develops other forms of cancer, potentially excluding the recruitment of the family).

This study has described families from widely differing environments in Europe and gives strong evidence for anticipation in familial pancreatic cancer. These findings may assist the creation of more informative family trees for linkage studies. Finally, the results of this study have immediate implications for genetic counselling and pancreatic cancer screening in high risk individuals from familial pancreatic cancer families.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grants from Cancer Research UK, Royal Liverpool University Hospital, Augustus Newman Foundation, the North West Cancer Research Fund, North West NHS Biomed Research Committee, an MRC Gastroenterology and Pancreas Research Co‐operative Grant, and the Deutsche Krebshilfe 70‐3085‐Ba4 Germany. There were no competing interests.

We are grateful for the work undertaken by L Vitone (EUROPAC Co‐ordinator), Margarete Schneider (FaPaCa study office), and R Mountford and to the following who, in addition to the co‐authors, have provided families and ongoing clinical information: Belgium: M Delhaye; Germany: L Estévéz‐Schwarz W von Bernstorff, M Colombo‐Benkmann, W Böck, K Breitschaft, S Dülsner, T Eberl, S Eisold, E Endlicher, M Ernst, L Estévéz‐Schwarz, B Gerdes, BM Ghadimi, TM Gress, R Grützmann, JW Heise, O Horstmann, L Jochimsen, C Jung, H Messmann, R Metzner, T Mundel, K Prenzel, O Pridöhl, J Rudolph, KM Schulte, C Schleicher, J Schmidt, K Schulmann, H Vogelsang H Witzigmann, N Zügel; Hungary: A Oláh, V Ruszinko; Italy: D Campra, G Uomo, S Pedrazzoli; Norway: Å Andrén‐Sandberg; Netherlands: J Jansen; UK and Ireland: A Brady, J Bennett, J Booth, L Botham, J Cahill, B Carmichael, C Chapman, O Claber, W Crisp, M Deakin, T Cole, J Cook, L Cowley, H Cupples, BR Davidson, G Davies, H Dorkins, DD Eccles, R Eeles, F Elmslie, G Evans, S Fairgrieve, C Faulkner, J Foster A Howick, M Hershman, S Hodgson, C Imrie, L Irvine, L Izatt, C Johnson, B Kerr, A Laucassen, S Laws, D Longdon, R Loke, D McBride, J MacKay, E Maher, M Mehta, C Mitchell, G Mitchell, P Morrison, K Pape, J Raeburn, E Sheridan, C Smith, G Sobala, R Sutton, J Thomson, S Tomkins, K Wedgwood P Zack; Sweden, E Bjorck, E Svarthol, J Permert, I Ihse.

Abbreviations

EUROPAC - European Registry of Hereditary Pancreatitis and Familial Pancreatic Cancer

FaPaCa - German National Case Collection for Familial Pancreas Cancer

G1 - generation 1

G2 - generation 2

G3 - generation 3

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Silverman D T, Schiffman M, Everhart J.et al Diabetes mellitus, other medical conditions and familial history of cancer as risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 1999801830–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemminki K, Li X. Familial and second primary pancreatic cancers: a nationwide epidemiologic study from Sweden. Int J Cancer 2003103525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein A P, Brune K A, Petersen G M.et al Prospective risk of pancreatic cancer in familial pancreatic cancer kindreds. Cancer Res 2004642634–2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartsch D K, Kress R, Sina‐Frey M.et al Prevalence of familial pancreatic cancer in Germany. Int J Cancer 2004110902–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giardiello F M, Offerhaus G J, Lee D H.et al Increased risk of thyroid and pancreatic carcinoma in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut 1993341394–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium: Cancer risks in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999911310–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giardiello F M, Brensinger J D, Tersmette A C.et al Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz‐Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology 20001191447–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartsch D K, Sina‐Frey M, Lang S.et al CDKN2A germline mutations in familial pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg 2002236730–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynch H T, Brand R E, Hogg D.et al Phenotypic variation in eight extended CDKN2A germline mutation familial atypical multiple mole melanoma‐pancreatic carcinoma‐prone families: the familial atypical mole melanoma‐pancreatic carcinoma syndrome. Cancer 20029484–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein A P, Beaty T H, Bailey‐Wilson J E.et al Evidence for a major gene influencing risk of pancreatic cancer. Genet Epidemiol 200223133–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn S A, Greenhalf B, Ellis I.et al BRCA2 germline mutations in familial pancreatic carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 200395214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eberle M A, Pfutzer R, Pogue‐Geile K L.et al A new susceptibility locus for autosomal dominant pancreatic cancer maps to chromosome 4q32‐34. Am J Hum Genet 2002701044–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutherland G R, Richards R I. Simple tandem DNA repeats and human genetic disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995923636–3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kehoe P, Krawczak M, Harper P S.et al Age of onset in Huntington disease: sex specific influence of apolipoprotein E genotype and normal CAG repeat length. J Med Genet 199936108–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grandbastien B, Peeters M, Franchimont D.et al Anticipation in familial Crohn's disease. Gut 199842170–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Annese V, Andreoli A, Astegiano M.et al Clinical features in familial cases of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in Italy: a GISC study. Italian Study Group for the Disease of Colon and Rectum. Am J Gastroenterol 2001962939–2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radstake T R, Barrera P, Albers M J.et al Genetic anticipation in rheumatoid arthritis in Europe. European Consortium on Rheumatoid Arthritis Families. J Rheumatol 200128962–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paterson A D, Kennedy J L, Petronis A. Evidence for genetic anticipation in non‐Mendelian diseases. Am J Hum Genet 199659264–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel A M, Andermann F, Badhwar A.et al Anticipation in familial cavernous angioma: ascertainment bias or genetic cause. Acta Neurol Scand 199898372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Lord C, Powles R, Mehta J.et al Familial acute myeloid leukaemia: four male members of a single family over three consecutive generations exhibiting anticipation. Br J Haematol 1998100557–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horwitz M, Goode E L, Jarvik G P. Anticipation in familial leukemia. Am J Hum Genet 199659990–998. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuille M R, Houlston R S, Catovsky D. Anticipation in familial chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leukemia 1998121696–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiernik P H, Wang S Q, Hu X P.et al Age of onset evidence for anticipation in familial non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma. Br J Haematol 200010872–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shugart Y Y, Hemminki K, Vaittinen P.et al A genetic study of Hodgkin's lymphoma: an estimate of heritability and anticipation based on the familial cancer database in Sweden. Hum Genet 2000106553–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shugart Y Y, Hemminki K, Vaittinen P.et al Apparent anticipation and heterogeneous transmission patterns in familial Hodgkin's and non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma: report from a study based on Swedish cancer database. Leuk Lymphoma 200142407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldstein A M, Clark W H, Jr, Fraser M C.et al Apparent anticipation in familial melanoma. Melanoma Res 19966441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong T, Howes N, Threadgold J.et al Molecular diagnosis of early pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in high risk patients. Pancreatology 20011486–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rulyak S J, Kimmey M B, Veenstra D L.et al Cost‐effectiveness of pancreatic cancer screening in familial pancreatic cancer kindreds. Gastrointest Endosc 20035723–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rieder H, Sina‐Frey M, Ziegler A.et al German national case collection of familial pancreatic cancer—clinical‐genetic analysis of the first 21 families. Onkologie 200225262–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rulyak S J, Lowenfels A B, Maisonneuve P.et al Risk factors for the development of pancreatic cancer in familial pancreatic cancer kindreds. Gastroenterology 20031241292–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai Y Y, Petersen G M, Booker S V.et al Evidence against genetic anticipation in familial colorectal cancer. Genet Epidemiol 199714435–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faybush E M, Blanchard J F, Rawsthorne P.et al Generational differences in the age at diagnosis with Ibd: genetic anticipation, bias, or temporal effects. Am J Gastroenterol 200297636–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fraser F C. Trinucleotide repeats not the only cause of anticipation. Lancet 1997350459–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howes N, Lerch M M, Greenhalf W.et al Clinical and genetic characteristics of hereditary pancreatitis in Europe. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 20042252–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsu L, Zhao L P, Malone K E.et al Assessing changes in ages at onset over successive generation: an application to breast cancer. Genet Epidemiol 20001817–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Picco M F, Goodman S, Reed J.et al Methodologic pitfalls in the determination of genetic anticipation: the case of Crohn disease. Ann Intern Med 20011341124–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bramhall S R, Allum W H, Jones A G.et al Treatment and survival in 13,560 patients with pancreatic cancer, and incidence of the disease, in the West Midlands: an epidemiological study. Br J Surg 199582111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nitecki S S, Sarr M G, Colby T V.et al Long‐term survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Is it really improving? Ann Surg 199522159–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sener S F, Fremgen A, Menck H R.et al Pancreatic cancer: a report of treatment and survival trends for 100,313 patients diagnosed from 1985–1995, using the National Cancer Database. J Am Coll Surg 19991891–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gouma D J, van Geenen R C, van Gulik T M.et al Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg 2000232786–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parkin D M, Bray F I, Devesa S S. Cancer burden in the year 2000. The global picture. Eur J Cancer 200137(suppl 8)4–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hruban R H, Canto M I, Yeo C J. Prevention of pancreatic cancer and strategies for management of familial pancreatic cancer. Dig Dis 20011976–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coughlin S S, Calle E E, Patel A V.et al Predictors of pancreatic cancer mortality among a large cohort of United States adults. Cancer Causes Control 200011915–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boyle P, Maisonneuve P, Bueno de Mesquita B.et al Cigarette smoking and pancreas cancer: a case control study of the search programme of the IARC. Int J Cancer 19966763–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kemm J R. A birth cohort analysis of smoking by adults in Great Britain 1974–1998. J Public Health Med 200123306–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trkova M, Hladikova M, Kasal P.et al Is there anticipation in the age at onset of cancer in families with Li‐Fraumeni syndrome? J Hum Genet 200247381–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paterson A D, Naimark D M, Huang J.et al Genetic anticipation and breast cancer: a prospective follow‐up study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 19995521–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McInnis M G. Anticipation: an old idea in new genes. Am J Hum Genet 199659973–979. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petronis A, Kennedy J L, Paterson A D. Genetic anticipation: fact or artifact, genetics or epigenetics? Lancet 19973501403–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thorlacius S, Sigurdsson S, Bjarnadottir H.et al Study of a single BRCA2 mutation with high carrier frequency in a small population. Am J Hum Genet 1997601079–1084. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dagan E, Gershoni‐Baruch R. Anticipation in hereditary breast cancer. Clin Genet 200262147–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]