Abstract

Objective:

To determine whether analyzing more lymph nodes in colon cancer specimens improves survival.

Summary Background Data:

Increasing the number of lymph nodes analyzed has been reported to correlate with improved survival in patients with node-negative colon cancer.

Methods:

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database was queried for all patients undergoing resection for histologically confirmed colon cancer between the years 1988 and 2000. Patients were excluded for distant metastases or if an unknown number of nodes was sampled. The number of nodes sampled was categorized into 0, 1 to 7, 8 to 14, and ≥15 nodes. Survival curves constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method were compared using log rank testing. A Cox proportional hazard model was created to adjust for year of diagnosis, age, race, gender, tumor grade, tumor size, TNM stage, and percent of nodes positive for tumor.

Results:

The median number of lymph nodes sampled for all 82,896 patients was 9. For all stages examined, increasing nodal sampling was associated with improved survival. Multivariate regression demonstrated that patients who had at least 15 nodes sampled as compared with 1 to 7 nodes experienced a 20.6% reduction in mortality independent of other patient and tumor characteristics.

Conclusions:

Adequate lymphadenectomy, as measured by analysis of at least 15 lymph nodes, correlates with improved survival, independent of stage, patient demographics, and tumor characteristics. Currently, most procedures do not meet this guideline. Future trials of adjuvant therapy should include extent of lymphadenectomy as a stratification factor.

Optimal resection for colon cancer includes proximal, distal, and radial margins. Adequate lymph node dissection of greater than 15 nodes also prolongs survival, even after adjusting for patient and tumor characteristics.

Despite advances in screening technologies and treatment, colon cancer continues to be a leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States, ranking second overall.1 Traditionally, colon cancers are categorized as either localized (stage I and stage II), regionally spread (stage III), or distantly spread (stage IV). The existence of nodal metastases has been the most important prognostic factor overall in determining long-term survival. Although stage I and II cancers were thought to be surgically curable, the rate of recurrence reaches 40%; recurrence rate after “curative” resection of stage III colon cancer is as high as 70%.2

Previous studies have reported a positive relationship between the number of nodes dissected and the survival of patients with stage II cancers.3,4 One potential explanation for this finding could be the failure to identify positive lymph nodes, leading to understaging. Scott and Grace5 estimated that the failure to identify at least 13 lymph nodes led to a false-negative rate of 10%. A secondary analysis of the Intergroup 0089 study of 5-fluorouracil with leucovorin and/or levamisole adjuvant therapy demonstrated that increasing the number of nodes analyzed improved survival in stage II and III patients.6 A mathematical model developed by Joseph et al7 allowed for calculation of the probability of a missed nodal metastasis based on the number of nodes examined. Based on these and other studies, various guidelines suggest minimums from 8 nodes to 40 nodes, including a recommendation from the College of American Pathologists for a 12-node minimum.3–12 Despite these recommendations, few trials report the number of nodes dissected in each group, and those that do typically do not have uniform compliance with guidelines. In a recent trial on the adjuvant use of oxaliplatin, only 65% of patients had more than 10 nodes sampled.13 Baxter et al14 demonstrated poor overall compliance with the UICC/American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/College of American Pathologists guideline of 12 nodes in colorectal cancers, with only 37% of cases meeting the guideline.

Our study examined the compliance of American surgeons with these suggested guidelines for colon cancer alone and the overall survival associated with compliance. We hypothesized that compliance with current guidelines for lymph node staging in colon cancer specimens would be poor and that patients undergoing a more extensive lymph node dissection would experience a survival benefit. A secondary objective was to compare survival rates associated with different guidelines.

METHODS

Data Source

Patients were selected by searching the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registry maintained by the National Cancer Institute. The SEER database is a collection of 13 population-based cancer registries that cover roughly 26% of the U.S. population.15 Data available include patient demographic data (eg, age, gender), tumor data (including grade, size, depth of invasion), nodal staging data (number of nodes examined, number of nodes positive), utilization of radiation therapy, vital status, and survival. Notably, the data does not include utilization of chemotherapy.

Patient Selection

All patients who underwent surgical resection of a histologically confirmed invasive colon cancer between 1988 and 2000 were selected. Patients were excluded if there was no information or insufficient information about the number of lymph nodes examined in the pathologic specimen. Patients were also excluded if a distant metastasis was diagnosed by the initial operation. Since the data has no personal identifiers, this study was exempt from Institutional Review Board review.

Analysis

All cases were restaged using current AJCC criteria.16 The mean, median, and mode of the number of lymph nodes examined were determined. Within each stage, cases were stratified into those with zero nodes, 1 to 7 nodes, 8 to 14 nodes, and 15 or greater nodes analyzed in the specimen. Subgroup analysis for those with 8 to 14 nodes compared survival between those with 8 or 9, 10 or 11, and 12 to 14 nodes in their specimens. Survival analysis was undertaken using the Kaplan-Meier method.17 Survival differences were analyzed utilizing the log-rank test.

A Cox proportional hazards model18 was used for multivariate analysis. Analyzed variables included age, gender, race (white vs. black vs. other), year of diagnosis (1988–1991, 1992–1995, 1996–2000), region (by SEER registry), tumor depth (by T-stage), nodal status (by N-stage), tumor grade, number of nodes examined within the specimen, and the percentage of nodes positive for tumor in the specimen. A forward stepwise methodology was used to screen variables for inclusion. We included variables with a P value of <0.05.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 11.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago IL). Significance levels were set at P < 0.05. All tests were 2 sided.

RESULTS

Of 119,757 patients initially identified, 10,874 patients were excluded for inadequate staging information and 21,890 patients were excluded for stage IV disease. An additional 4097 patients were excluded for inadequate lymph node examination data (either no data were recorded or the number analyzed was not recorded). This left 82,896 patients eligible for analysis. Demographics of the patients were similar (Table 1) in each group within each stage, although due to the large numbers of patients, all differences were significant at the P < 0.05 level.

TABLE 1. Patient Demographics

Variations in guideline compliance by the location of the patient (by SEER registry) were evident. The median number of sampled nodes across all patients was 9. The percentage of patients with ≥15 nodes analyzed ranged from 22.5% to 38.6% among the 13 SEER registries (Fig. 1). Only 4 regions reached a compliance rate of 25% for analysis of a minimum of 15 nodes; only 5 regions reached a compliance rate of 50% for analysis of at least 10 nodes. Perhaps not surprisingly, the analysis of at least 15 nodes tended to be more common in the most recent time interval (1996–2000): 28.9% of patients as compared with 24.3% for 1988 to 1991 (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 1. Nodal examination by SEER Registry. x-axis abbreviations: AK, Alaska; ATL, Atlanta; CT, Connecticut; DTW, Detroit; GA, rural Georgia; HI, Hawaii; IA, Iowa; LAX, Los Angeles; NM, New Mexico; SEA, Seattle Puget Sound; SFO, San-Francisco-Oakland; SJO, San Jose; UT, Utah.

FIGURE 2. Nodal examination by year of diagnosis.

The rate of detection of nodal metastasis, particularly in N2 disease, increased with the number of nodes sampled (Fig. 3). This difference was most pronounced in T1 (6.5% vs. 11%) and T4 lesions (45.8% vs. 51.5%). T2 and T3 lesions had a smaller difference (14.7% vs. 16.7% and 39% vs. 41.9%, respectively).

FIGURE 3. N stage by extent of nodal sampling.

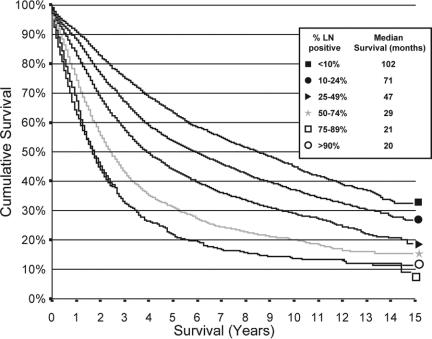

Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrated an improvement in survival in those with ≥15 nodes analyzed as compared with 0, 1 to 7, and 8 to 14 nodes (Fig. 4). Each difference was statistically significant by log-rank testing. Improvements in median survival for patients ≥15 nodes as compared to patients with 1–7 nodes sampled, were 11 months in stage I, 54 months in stage II, and 21 months in stage III (Table 2). Further subgroup analysis demonstrated no statistically difference in survival between patients with into 8 or 9, 10 or 11, and 12 to 14 nodes (Table 3). When broken down by AJCC substage, this result held up even when analyzing stages IIA and IIB separately, as well as IIIB and IIIC, although IIIA patients no longer exhibited this effect (P = 0.79) (Table 2). Within stage III patients, the percentage of lymph nodes positive also proved to be a powerful independent predictor of survival (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 4. Survival by extent of nodal examination and stage. A, AJCC stage I. B, AJCC stage II. C, AJCC stage III.

TABLE 2. Median Survival (months) by AJCC Staging and Number of Lymph Nodes Examined

TABLE 3. Median Survival (months) for Those With 8 to 14 Nodes by AJCC Stage and Number of Nodes Examined

FIGURE 5. Survival by percentage of lymph nodes positive in stage III colon cancer.

Multivariate analysis demonstrated that, even after adjusting for patient demographics, tumor characteristics, and patient location by SEER registry, survival was still correlated with a 20.6% decrease in mortality for those with >15 lymph nodes examined in the specimen as compared with only 1 to 7 nodes. Other factors that positively affected survival included a lower T-stage, lower N-stage, lower tumor grade, tumor site, lower percentage of resected nodes positive for tumor, more recent year of diagnosis, younger patient age, female gender, nonblack race, as well as location by SEER registry with the San Jose and Seattle registries being the lowest risk (Table 4).

TABLE 4. Multivariate Regression Analysis

DISCUSSION

Over the years, colon cancer staging has evolved to include depth of invasion, presence of nodal metastases, and number of tumor-involved nodes. The extent of an adequate resection has also evolved, progressing from a simple colonic resection to the current standard of utilizing the base of the mesentery as an anatomic landmark.19 More recently, the extent of lymph node examination has become a topic of interest. Simple intuition has always led us to believe that a higher node count would yield a better quality diagnosis and resection. Despite this, retrospective single institution studies,12 secondary analyses of multicenter studies,6,11 and population-based studies,8,20 have noted the poor yield of lymph nodes in many specimens. Studies of survival in various stages of colon cancer (primarily stage II) have generally concluded that the resection of too few nodes is a poor prognostic indicator. This study confirms this conclusion and extends it across stages I, II, and III.

While statistically significant, perhaps what is most impressive is the clinical significance of these findings. The resection of at least 15 nodes prolonged median overall survival by 11 months in patients with stage I disease, 54 months in stage II disease, and 21 months in stage III disease. These differences are on par or better than the best reported results for various adjuvant chemotherapies with even the newest combination adjuvant chemotherapy regimens.

The reason for the marked improvement is likely to be multifactorial. One explanation, particularly in stage I and II cancers, is the well-described phenomenon of stage migration. The higher the number of nodes examined, the lower the risk of a missed nodal metastasis through the failure to resect the relevant lymph node or the failure to analyze the node. The likelihood that increasing the number of nodes analyzed would lead to upstaging from stage I or II to stage III disease seems to be confirmed by our study.

Even within AJCC stage III cancers, stage migration can occur from substages IIIA (T1–2N1) and IIIB (T3–4N1) to IIIC (T1–4N2). However, since we first analyzed all stage III patients as one group, this effect should be minimized, since even those upstaged would have still been analyzed together. The effect might be falsely elevated if IIIC patients were routinely treated differently than IIIA and IIIB patients; however, this seems unlikely because the adjuvant chemotherapy regimens that were usually used during this time period did not include irinotecan or oxaliplatin. Furthermore, the improvement in survival continued to be very pronounced even in stage IIIC patients.

Patients with a larger number of lymph nodes analyzed were more likely to be diagnosed with N2 disease. This may reflect a selection bias beyond simple upstaging since those with extensive nodal disease may have received wider mesenteric resections. This bias would have compressed the difference that we found in stage III cancers; thus, the effect of adequate nodal examination is likely to be even greater than reported here.

Surgeon skill or operation selection is likely to be at least a contributing factor. Reinbach et al21 described a trend toward an increase in the number of nodes (13 vs. 7.5) in colorectal cancer specimens from surgeons with a particular colorectal interest as compared with those without such an interest. In our patient group, the most common number of nodes dissected was zero, indicating that many colon cancer patients received operations not based on standard oncologic principles. While improvement was noted over time, even in the most recent period examined, the majority of patients did not have even 10 lymph nodes examined. (Fig. 2)

We chose to study only colon cancer to eliminate the issues of pelvic anatomy in rectal cancer and thereby decrease the variation in patient factors that might prevent the opportunity for an adequate excision. Similarly, we excluded stage IV patients to decrease the likelihood that differences in survival might be related to patient selection bias toward palliative surgery in those receiving little or no lymph node dissection.

Variation in pathologic technique and skill must also be considered. Different pathologists and assistants may have markedly different nodal yields on average. Temporal variation in our group may reflect an increasing awareness among pathologists of the importance of analyzing a large number of lymph nodes. This has resulted in a recommendation of examining all palpable lymph nodes.22 This differing emphasis between pathology groups is reflected in the geographic variation seen in our sample. The Hawaii region had very high yields of nodal examination as compared with other regions, which may reflect the efforts previously reported by Wong et al23 to ensure the pathologic examination of high numbers of nodes in colon cancer specimens in Hawaii. Differences in utilization of various fat clearing techniques may also play a role in the number of lymph nodes found in a specimen.5 Beyond a failure of nodal staging, the failure to pathologically examine all nodes within a specimen might also reflect an increase in inaccuracies in other types of examination, such as radial margins in colon cancer. Failure to achieve a negative margin in the primary tumor both radially and proximally/distally can be a negative prognostic factor.11

Our study's correlation between high percentages of positive nodes in a specimen and poor prognosis may indicate the need for a nodal “margin.” For rectal cancer, total mesorectal excision is essential in reducing local recurrence and improving overall survival.24,25 Previous work has found that the percentage of nodes examined that were found to be positive was negatively associated with prognosis in breast cancer26,27 and gastric cancer.28,29 This correlation was also seen in colon cancer in a secondary analysis of the Intergroup 0089 study.30 This finding may indicate that, similar to the need to have a radial, proximal, and distal margin, a nodal “margin” may also be required for optimal outcomes. Failing to clear the body of tumor in the form of macrometastases or perhaps even micrometastases in lymph nodes may result in a tumor burden or a nidus for future metastasis that ultimately results in decreased survival.

One aspect of care that we were not able to adjust for in this analysis is the use of chemotherapy in these cohorts. Data from the National Cancer Database (NCDB) has shown an increase in the use of adjuvant chemotherapy from 39% to 64% in stage III colon cancers between the years of 1991 and 2002.31 Schrag et al32 reported an overall usage of 55% for 1991 to 1996 in the SEER-Medicare population, with 78% of the youngest elderly (ages 65–69 years) receiving chemotherapy. For stage II colon cancers, Schrag et al33 also reported that 27% of those in the SEER-Medicare database for those same years received adjuvant therapy. The NCDB website similarly reports nearly 19% use of adjuvant therapy for stage II colon cancers in 2000.34 Since adjuvant therapy confers a survival advantage in stage III of up to 16% at 5 years, some of the improvement associated with sampling more nodes may reflect an increase in the use of adjuvant therapy. However, our multivariate model included the year of diagnosis by 4-year increments; we found that those with at least 15 nodes analyzed continued to have better survival than those with 1 to 7 nodes sampled even after adjusted for year of diagnosis.

Although the improvement in survival may stem from multiple causes, the overall survival benefit from ensuring adequate resection and examination is on par or better than the survival advantage conferred by adjuvant therapy in stages II and III colon cancer. Inadequate lymph node examination in colon cancer resections should be treated as a marker of a high risk for recurrence and a poorer prognosis. The failure to achieve an adequate nodal examination may be an indication to consider adjuvant chemotherapy at lower stages of colon cancer, although this needs to be further studied prospectively to determine benefit.

Surgeons should strive to achieve a minimum of 15 nodes in any dissection by ensuring an adequate mesenteric resection whenever a colon resection is undertaken for a mass lesion. When adequate resection has been performed, the surgeon should request a reexamination of the specimen if 15 nodes are not analyzed by the pathologist. The use of specialized fat-clearance techniques5,35 should be considered if 15 nodes are unable to be located within the specimen. Surgeons and pathologists who consistently obtain low lymph node examination counts in their colon cancer specimens should reexamine their processes to ensure that the number of lymph nodes resected and the number identified in specimen processing is maximized. The number of lymph nodes in colon cancer specimens may be a reasonable internal quality control indicator to follow trends in the surgical and pathologic adequacy of colon cancer care.

Future trials of staging technologies, such as sentinel lymph node mapping, immunohistochemical staining, and polymerase chain reaction analysis, should ensure that their accuracy is compared with adequately staged patients. However, based on our data, improved staging techniques should not be used to substitute for an adequate nodal dissection. Future therapeutic trials, including adjuvant therapy trials, should consider establishing a minimum number of lymph nodes analyzed in the primary specimen for enrollment or report results adjusted for the number of lymph nodes examined to identify potential confounders.

Discussions

Dr. Heidi Nelson (Rochester, Minnesota): I congratulate Dr. Bilchik and Dr. Chen for an excellent paper on a most important and timely topic. The data they presented enhances what we know to be true regarding the importance of removing and assessing lymph nodes as part of colon cancer surgery. What we first understood about the importance of adequate surgical removal and pathologic examination of lymph node pertained to node negative, Stage II, colon cancer. Several reports described an inverse and linear relationship between the number of nodes examined and observed survival rates. It was no challenge to imagine how insufficient lymph node sampling in Stage II disease could lead to understaging, undertreatment and poor oncologic outcomes.

What we now learn from Dr. Bilchik is that the same effect is true for all curable stages of colon cancer. A 21% reduction in mortality is associated with a lymph node sampling of 15 nodes as compared with 1–7 nodes. The same dramatic impact of lymph node harvest on survival has been demonstrated for both N1 and N2 node positive disease (J Clin Oncology. 2003;21:2912–2919). These findings in Stage III disease speak to an impact that transcends simple understaging and undertreatment. At a minimum, it reinvigorates the discussion on the importance of the surgical lymphadenectomy.

The clinical value of an extended lymphadenectomy in colon cancer has been the subject of both prospective clinical trials and retrospective clinical reviews; these prior studies failed to disclose a benefit for extended lymphadenectomy. Can the authors reconcile the fact that prior studies demonstrate no survival advantage for high mesenteric vascular ligation and yet according to their study, the more nodes harvested the better the survival? These discrepant results suggest a multifactorial answer including contributions from both pathology and surgery; ie, staging and treatment effects and even perhaps an interaction between surgery and adjuvant therapy. For cancers of the colon, rectum, stomach, and breast, the percent positive nodes (ie, thoroughness of lymphadenectomy) inversely correlates with survival. This likely reflects the importance of surgical quality or it could be a surrogate for other variables such as radial margins. Alternatively, it could have a biologic basis, specifically the adverse outcomes could be a reflection of the effect of residual micrometastatic disease. It seems appropriate to now ask whether the availability of effective chemotherapy could have increased the importance of adequate lymph node clearance. Does less residual disease enhance the chance for cure with postop chemotherapy?

Assuming it will take time for us to further sort out the role of surgery and pathology in the lymph node harvest issue, in the meantime, what can we do about the fundamental need for better lymph node harvests? National guidelines recommending a minimum 12 node harvest have been in print supported by the College of American Pathologist and an NCI-sponsored surgical group since the year 2000 (Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:979–997) (J Nat'l Ca Inst. 2001;93:583–596). Despite this, only 44% of patients receive an adequate lymph node evaluation (J Nat'l Ca Inst. 2005;97:219–225). Perhaps it is time to move this into the arena of “quality” initiatives. Should institutional, surgeon, and pathologist performance be measured and/or reimbursed based on a minimum of 12 nodes for colon cancer?

Finally, what are the implications of these findings for the future of targeted therapies in GI malignancies, including sentinel lymph node biopsy for colon cancer and local excision for rectal cancer? How do the authors see these findings influence or not future efforts to reduce the magnitude of surgery? Based on these findings, we must ask if we are proceeding in the right direction with less invasive surgeries.

Dr. Steven L. Chen (Santa Monica, California): The National Cancer Institute 2000 guidelines published in your study (J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:583–96) state that lymph node resections should extend to the level of the origin of the primary feeding vessels, and that atypical nodes should be removed when feasible and tagged for pathologic evaluation. Despite these clear recommendations, improvements in survival rates reported in the literature have been nonuniform and even contradictory. One contributing factor might be a failure to separate results for colon cancer and rectal cancer; in many cases we do not know how many of the patients underwent total mesorectal excision versus high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery, a procedure that might have left residual tumor. Another contributing factor might be a failure to separate results for node-positive and node-negative patients, as was the case for the French trial of hemicolectomy versus segmental colectomy (Dis Colon Rectum 1994;37:651–659). At the John Wayne Cancer Institute, we advocate maximal resection of the mesentery with removal of nodes up to the base of the feeding vessel. This improves tumor clearance and staging without significantly increasing operative morbidity or mortality.

With respect to your question on chemotherapy and residual disease, earlier this year we presented the results of meta-analysis of nodal staging in lymph node negative colon cancer (Society of Surgical Oncology, Annual Meeting, 2006). We showed that molecular (PCR) detection of micrometastases missed by standard hematoxylin/eosin staining was associated with about a 20% lower rate of survival. This difference indicates that the presence of micrometastatic foci might be an indication for chemotherapy. Furthermore, today's data from this study might suggest that clearing these micrometastases surgically may also be of some benefit or at a minimum, reduce tumor burden to make chemotherapy more effective.

In response to your question about how to improve lymph node harvest, the first step is raising awareness. Your work and the recommendations of the College of American Pathologists have effectively accomplished this. A review of the literature shows that groups who have published extensively on this topic tend to resect more than 12 nodes. I certainly would encourage all surgeons to examine their own results.

How will our findings affect sentinel node biopsy and local excision? First, this data reinforces the idea that in contrast to other malignancies such as breast cancer and melanoma, sentinel node mapping in colon cancer should not be used as a substitute to adequate nodal dissection. Our study clearly shows that failing to resect an adequate number of lymph nodes adjacent to a tumor-positive node is associated with worse outcomes. Sentinel node mapping may, on the other hand, help identify which nodes are most likely to harbor metastases and may improve the detection of micrometastases by allowing serial sectioning with immunohistochemical staining and/or PCR. We are currently conducting a prospective multicenter trial to address the question whether these micrometastases detected in sentinel nodes are clinically significant. As to the issue of local excision, this has been largely a question related to rectal cancer. Although we did not include rectal cancer in our study, I speculate that local excision will eventually prove to have a high failure rate, as shown by a recent analysis of the National Cancer Data Base (American Society of Clinical Oncology, Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium 2006). The American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z6041 trial is examining the outcome of local excision of rectal cancer (T2N0) after neoadjuvant chemoradiation.

I would advise surgeons to remember that the number of nodes makes a difference. When you are sure that the en-bloc specimen includes enough nodes but the pathology report shows no more than 10, ask the pathologist to re-examine the specimen and use specialized fat-clearance techniques if needed to search for more nodes in the specimen.

Dr. R. Scott Jones (Charlottesville, Virginia): I want to compliment Dr. Chen and Dr. Bilchik on this very important paper. I think it has revealed insights into a question that we have all pondered for a number of years. But what I want to speak about is a little over a year ago the National Quality Forum extended invitations for the submission of quality measures for breast cancer and colon cancer. Dave Winchester, Clifford Ko and Steve Edge, representing the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer, developed a series of measures for both of those diseases. But I would like to speak specifically about the colon measures, because included in that was a recommendation that 19* lymph nodes be removed with colon cancer specimens as a quality measure. That is still going through the process of the National Quality Forum, and we expect that to be completed in July. There will be a contract between National Quality Forum and the American College of Surgeons to pursue this and develop the monitoring of this measure with the National Cancer Database.

So, I predict that on the basis of your work and putting in quality measures, which everyone will be expected to acknowledge, that we will see a rather remarkable increase in the number of lymph nodes reported in surgical specimens during the next few years.

I would add parenthetically that one large insurance company has already put this measure in practice before it has even gotten through the National Quality Forum. So you can rest assured that the payors are going to pay attention to the number of lymph nodes in specimens hereafter.

I would add parenthetically that one large insurance company has already put this measure in practice before it has even gotten through the National Quality Forum. So you can rest assured that the payors are going to pay attention to the number of lymph nodes and specimens hereafter.

Dr. Steven L. Chen (Santa Monica, California): We did find that a 19-node minimum resulted in slightly better survival than a 15-node minimum. However, the number of nodes identified in a specimen drops off fairly quickly after 10 nodes; only 13% of specimens contained 19 nodes. I agree that the number of dissected nodes is a potentially useful indicator of quality because it is an evidence-based, quantifiable assessment. I am always hesitant to tie reimbursement to something that we do not fully understand how to achieve, but industry often has no such qualms. Given the paucity of other evidence-based process measures, this is not an unreasonable one.

Dr. David A. Rothenberger (Minneapolis, Minnesota): I would like to raise an issue that you hinted at, and that is the possibility that the differences you report are really a reflection of institutional cultural bias.

For instance, you have excluded all patients with known metastases. If a patient is unfortunate enough to be cared for in an institution where routine staging with high quality imaging is not a part of the routine practice, then distant metastases may not be detected. Your study would ascribe the patient's subsequent demise to poor results in comparison to non-metastatic patients rather than properly identifying the metastases and excluding the patient from your analysis.

Similarly, the same sort of institution may be the type that does not question the practice of doing wedge resections for colon cancer as opposed to a more standard radical cancer operation. Likewise, such an institution may not have a method to assure that patients with positive nodes are treated with appropriate modern chemotherapy as an adjuvant. Is there any way to look at the potential of such a cultural/institutional bias in your series? I suspect that is not possible with the SEER database. Thank you for presenting this information.

Dr. Steven L. Chen (Santa Monica, California): Although information on adjuvant chemotherapy is not included in the main SEER database, it can be obtained from the SEER-Medicare database. More readily available is the recent literature, a survey of which indicates that most patients, particularly those with stage III disease, are receiving chemotherapy. I agree that an institution's culture largely defines its practices. However, in a national database these local cultural biases would be most unlikely to affect overall results.

Dr. Hartley S. Stern (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada): Two quick questions. One, why 15? There is some confusion now as to 12, 15, or 19. And if we are going to pick a cut point, should we not pick one that is likely to be achievable in terms of the QI project? The second is, what were the numbers of those patients who did not get any staging, that is the nodes weren't commented on? Because again, if we are looking forward to a quality improvement project those patients with no nodes sampled are effectively in the same group as those who have a very few number of nodes sampled.

And the final comment I would make, in the Province of Ontario, which is 12 million people, we have begun an intervention project that I hope to be able to submit to next year's program in which we have looked at those interventions that actually make a difference. Andy Smith and Francis Wright of Ontario have been working on this. We, too, have 75% of our patients understaged, roughly the same figures you are getting in an entire population. And the 2 factors that seem to work best at quadrupling the lymph nodes are a specific intervention that Andy has designed to go into hospitals and workshops, along the lines of Dr. Pellegrini's comments, with the chief of surgery and the chief of pathology services present and designing locally specific interventions. And the second most important intervention was the hiring of another pathology technician.

Dr. Steven L. Chen (Santa Monica, California): When we examined the data on both 12- and 15-node cutoffs, we found that 15 was significantly better than 12. Adequate staging information (number of dissected nodes) was unavailable for about 12% (10,800/90,000) of patients. Additionally, 6000 patients underwent resection of zero nodes, which obviously is inadequate for staging and thus analyzed as a separate group.

I think that an institution-specific intervention such as you describe is an excellent idea and merits development as a quality indicator.

Footnotes

*This number should have been 12 according to Dr. Jones.

Supported by the Rod Fasone Memorial Cancer Fund (Indianapolis, IN), the Henry L. Guenther Foundation (Los Angeles, CA), the William Randolph Hearst Foundation (San Francisco, CA), the Davidow Charitable Fund (Los Angeles, CA), the Point Grey Charitable Trust, Gary Coull Trustee (Hong Kong, China), and Mr. and Mrs. Sheldon E. Stunkel and Mrs. Carolyn Dirks (Los Angeles, CA).

Reprints: Anton J. Bilchik, MD, PhD, John Wayne Cancer Institute, 2200 Santa Monica Blvd, Santa Monica, CA 90404. E-mail: bilchika@jwci.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDonald JS. Adjuvant therapy of colon cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:202–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swanson RS, Compton CC, Stewart AK, et al. The prognosis of T3N0 colon cancer is dependent on the number of lymph nodes examined. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prandi M, Lionetto R, Bini A, et al. Prognostic evaluation of stage B colon cancer patients is improved by an adequate lymphadenectomy: results of a secondary analysis of a large scale adjuvant trial. Ann Surg. 2002;235:458–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott KW, Grace RH. Detection of lymph node metastases in colorectal carcinoma before and after fat clearance. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1165–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Voyer TE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, et al. Colon cancer survival is associated with increasing number of lymph nodes analyzed: a secondary survey of Intergroup trial INT-0089. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2912–2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joseph NE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, et al. Accuracy of determining nodal negativity in colorectal cancer on the basis of the number of nodes retrieved on resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maurel J, Launoy G, Grosclaude P, et al. Lymph node harvest reporting in patients with carcinoma of the large bowel: a French population-based study. Cancer. 2000;82:1482–1486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fielding LP, Aresnault PA, Chapuis PH, et al. Working party report to the World Congress of Gastroenterology, Sydney 1990. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;6:325–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong JH, Severino R, Honnebier MB, et al. Number of nodes examined and staging accuracy in colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2896–2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ, et al. Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer: College of American Pathologists consensus statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:979–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein NS, Weldon S, Coffey M, et al. Lymph node recovery from colorectal resection specimens removed from adenocarcinoma: trends over time and a recommendation for a minimum number of lymph nodes to be recovered. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;106:209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baxter NN, Virnig DJ, Rothenberger DA, et al. Lymph node evaluation in colorectal cancer patients: a population-based Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;95:219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Cancer Institute. Overview of the SEER Program. Available on the World Wide Web at http://seer.cancer.gov/about/. Accessed March 29, 2006.

- 16.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed, New York: Springer-Verlag, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observation. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson H, Petrelli N, Carlin A, et al. Guidelines 2000 for colon and rectal cancer surgery. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:583–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright FC, Law CHL, Last L, et al. Lymph node retrieval and assessment in stage II colorectal cancer: a population based study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:903–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinbach DH, McGregor JR, Murray GD, et al. Effect of the surgeon's specialty interest on the type of resection performed for colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:1020–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein NS. Lymph node recoveries from 2427 pT3 colorectal resection specimens spanning 45 years: recommendation on minimum number of recovered lymph nodes based on predictive probabilities. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong JH, Johnson DS, Hemmings D, et al. Assessing the quality of colorectal cancer staging: documenting the process in improving the staging of node-negative colorectal cancer. Arch Surg. 2005;140:881–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enker WE, Thaler HT, Cranor ML, et al. Total mesorectal excision in the operative treatment of carcinoma of the rectum. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:335–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Truong PT, Berthelet E, Lee J, et al. The prognostic significance of the percentage of positive/dissected axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer recurrence and survival in patients with one to three positive axillary nodes. Cancer. 2005;103:2006–2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Wal BC, Butzelaar RM, van der Meij S, et al. Axillary lymph node ratio and total number of removed lymph nodes: predictors of survival in stage I and II breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J, Cheong JH, Hyung WJ, et al. Predictors of long-term survival in pN3 gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2004;88:9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez Santiago JM, Munoz E, Marti M, et al. Metastatic lymph node ratio as a prognostic factor in gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berger AC, Sigurdson ER, LeVoyer T, et al. Colon cancer survival is associated with decreasing ratio of metastatic to examined lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8706–8712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jessup JM, Stewart A, Greene FL, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer: implications of race/ethnicity, age, and differentiation. JAMA. 2005;294:2703–2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schrag D, Cramer LD, Bach PB, et al. Age and adjuvant chemotherapy use after surgery for stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:850–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schrag D, Rifas-Shiman S, Saltz L, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy use for Medicare beneficiaries with stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3999–4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Cancer Database. Stage/treatment of colon cancer diagnosed in 2000. Available on the World Wide Web at http://web.facs.org/ncdbbmr/frames/public7/TABLES/Y00S14XaTa_15190000_Tb_B.html Accessed March 28, 2006.

- 35.Haboubi NY, Clark P, Kaftan SM, et al. The importance of combining xylene clearance and immunohistochemistry in the accurate staging of colorectal carcinoma. J R Soc Med. 1992;85:386–388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]