Abstract

Objective:

To report the results of a multicenter experience of split liver transplantation (SLT) with pediatric donors.

Summary Background Data:

There are no reports in the literature regarding pediatric liver splitting; further; the use of donors weighing <40 kg for SLT is currently not recommended.

Methods:

From 1997 to 2004, 43 conventional split liver procedures from donors aged <15 years were performed. Nineteen donors weighing ≤40 kg and 24 weighing >40 kg were used. Dimensional matching was based on donor-to-recipient weight ratio (DRWR) for left lateral segment (LLS) and on estimated graft-to-recipient weight ratio (eGRWR) for extended right grafts (ERG). In 3 cases, no recipient was found for an ERG. The celiac trunk was retained with the LLS in all but 1 case. Forty LLSs were transplanted into 39 children, while 39 ERGs were transplanted into 11 children and 28 adults.

Results:

Two-year patient and graft survival rates were not significantly different between recipients of donors ≤40 kg and >40 kg, between pediatric and adult recipients, and between recipients of LLSs and ERGs. Vascular complication rates were 12% in the ≤40 kg donor group and 6% in the >40 kg donor group (P = not significant). There were no differences in the incidence of other complications. Donor ICU stay >3 days and the use of an interposition arterial graft were associated with an increased risk of graft loss and arterial complications, respectively.

Conclusions:

Splitting of pediatric liver grafts is an effective strategy to increase organ availability, but a cautious evaluation of the use of donors ≤40 kg is necessary. Prolonged donor ICU stay is associated with poorer outcomes. The maintenance of the celiac trunk with LLS does not seem detrimental for right-sided grafts, whereas the use of interposition grafts for arterial reconstruction should be avoided.

A multicenter experience of split liver transplantation with pediatric donors revealed that this strategy can effectively increase organ availability, with a benefit for both adult and pediatric patients. The use of partial grafts from donors weighing less than 40 kg needs careful assessment.

Despite the worldwide acceptance of split liver transplantation (SLT) as a strategy to expand a limited donor pool, problems still exist in its widespread application.1 The technique of “conventional” SLT divides the liver of a heart-beating donor into an extended right graft (ERG) and a left lateral segment graft (LLS), including Couinaud segments I, IV–VIII, and segments II–III, respectively.2,3 Recent single-center series of either in situ or ex situ SLT reported results comparable to whole liver transplantation (WLT).3–16

The ideal split liver donor should be between 14 and 50 years of age, with good liver function, serum sodium level <160 mmol/L, short intensive care unit (ICU) stay, stable hemodynamics, and with a grossly normal liver.15,17,18

It has been shown that conventional splitting can yield a 15% increase in the number of grafts when donors within the above criteria are selected, and a 43% increase if donors with only one missing criterion are included.18 We had satisfactory results by extending the donor age beyond 50 years;19 while the lower age limit is still unclear, the splitting of donors younger than 10 years,17,20 or weighing less than 40 to 45 kg15,18 remain questionable.

The recipients of LLSs are usually pediatric patients, while ERGs are transplanted into adolescents or adults. In the case of children less than 5 to 6 kg, SLT from an adult donor often means the transplantation of a large-for-size graft causing a number of complications, including graft dysfunction.21 The use of a single liver segment or of the LLS from a pediatric donor can circumvent this problem. The success of the former strategy has already been reported.22 Conversely, there are no data specifically addressing SLT from pediatric donors, particularly from those aged less than 10 years or weighing less than 40 kg. A corollary of this limitation is the unknown fate of the right-sided graft.

Since 1997, an extensive application of SLT began in the Northern Italian Transplant (NITp) area with the intention of satisfying the shortage of organs for pediatric recipients8 and pediatric donors are considered for splitting when small children are on the waiting list. We report herein the results of a prospective multicenter study evaluating the outcome of SLT from donors younger than 15 years.

METHODS

From October 1997 to July 2004, 43 split liver procedures were carried out in donors younger than 15 years. In all cases, an LLS and an ERG were procured. In 7 cases (16%), both LLS and ERG were transplanted at the same center; in 33 cases (77%), the grafts were transplanted in 2 different centers. In 3 cases (7%) in which the donor weight was <40 kg (20, 20, and 30 kg, respectively), no recipient could be found for the ERG, and only the LLS was transplanted. In 7 cases the grafts were shared with a European liver transplant center. Only AB0-compatible donors were used.

One child was excluded from the analysis having received a combined split liver (LLS) and kidney transplant. Another pediatric recipient of a combined split liver (LLS) and small bowel transplant, subsequently retransplantated for hepatic artery thrombosis (HAT) with an LLS from another pediatric donor, was also excluded from the analysis. Overall, 80 isolated SLTs with grafts from pediatric donors were performed. The 73 SLTs performed by Italian Centers represented 16% of the 453 SLTs performed in Italy during the same period.

Data on demographic and clinical profiles of recipients, procurement and transplant technique, postoperative complications, causes of death, and retransplantation and actual patient and graft status recorded by the transplant centers were collected by completion of appropriate forms. A full response was obtained for 79 of 80 transplants (99%), with data available for 40 of 40 LLSs (100%) and 39 of 40 ERGs (97%). A 1-month-old girl with neonatal hemochromatosis with subacute liver failure had a primary transplant with an LLS from a donor ≤40 kg; she subsequently developed chronic rejection and was retransplantated with an LLS from a donor >40 kg. The patient population therefore included 78 recipients: 50 children, who received 40 LLSs and 11 ERGs, and 28 ERG adult recipients. The pediatric population included 25 males and 25 females, with a mean age of 3.2 ± 4.0 years (median, 1.0 year; range, 1 month to 12 years). The adult population included 5 males and 23 females, with a mean age of 46.1 ± 13.8 years (median, 50 years; range, 17–66 years).

Criteria for Splitting

The following donor characteristics were considered ideal for splitting: 1) no past history of liver dysfunction/damage, 2) liver function tests within 5-fold normal values, 3) normal macroscopic appearance of the graft, and 4) hemodynamic stability.8 In some cases, criteria were liberally extended by agreement between centers.

In the NITp area, liver grafts from pediatric donors (<15 years) are offered to pediatric recipients (listed for transplant before the age of 15 years). Donors are allocated to centers with pediatric liver transplant programs according to rotation criteria, with the exception of UNOS status 1 patients to whom the first available donor is assigned. The assigned center allocates the graft to the most urgent recipient with an adequate dimensional matching. Dimensional matching is usually established as follows: 1) If donor-to-recipient weight ratio (DRWR) is <2, a WLT is performed; 2) if DRWR is between 2 and 12, and donor characteristics satisfy criteria for splitting, the patient is a potential recipient of an LLS, and a split procedure is considered. The volume of the ERG obtainable from that donor, assumed to be 75% of the whole donor liver mass, is estimated using the formula proposed by Urata et al.23 An ERG is offered to a pediatric recipient with an estimated graft-to-recipient weight ratio (eGRWR) ≥1% and <5%. If no pediatric recipients of ERG are found, the ERG is offered to an adult recipient.

Surgical Techniques

The splitting procedure was performed in situ, without special surgical equipment and according to the technique described by Rogiers et al,4 except in 1 case where the parenchymal division was carried out ex situ for logistical reasons. Briefly, the operation started with the identification of the full course of the left hepatic artery and of the portal vein, as well as the origin of the right hepatic artery. The presence of aberrant arterial branch(es) was carefully checked. When the arterial branch to segment IV originated from the right hepatic artery, it was usually preserved, while when it originated from the left, proper or common hepatic artery it was usually interrupted. The liver was divided so as to obtain an ERG (including segments IV–VIII, plus the caudate lobe) and an LLS (including segments II and III). The LLS included the left hepatic vein, the left branch of the portal vein and, in all but 1 case, the left hepatic artery in continuity with the celiac trunk. The ERG included the vena cava, the portal trunk, the right hepatic artery, and the common bile duct. The LLS had an accessory left hepatic artery in 3 cases (7%), and a replaced one originating from the left gastric artery in 5 (12%). The ERG had a replaced right hepatic artery in 2 cases (5%), an accessory right hepatic artery in 3 cases (8%), and a hepato-mesenteric trunk in 1 case (3%). In no case did the split procedure jeopardize the viability of other organs.

Regarding the transplantation procedure, technical details on venous outflow reconstruction were not specifically requested in the data form. In LLS recipients, direct portal vein anastomosis was performed in 33 cases (83%), while a venous graft harvested from the donor was used in 7 cases (17%). The arterial reconstruction was performed via a direct anastomosis in 37 cases (93%), and with interposition of an arterial graft in 3 (7%). A Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was used for biliary reconstruction, made on a single duct in 32 cases (80%) and on 2 ducts in 7 cases (17%). In 1 case (3%), no details were provided on the number of anastomosed ducts.

In ERG recipients, no information was available on vascular and biliary reconstructions in 2 cases (5%). A venous graft for portal anastomosis was used in 1 case (3%), and an arterial interposition graft in 13 cases (33%). An interposition graft was used in 3 of 11 children (27%) and in 10 of 26 adults (38%), and in 5 of 15 recipients from donors ≤40 kg (33%) and in 8 of 22 recipients from donors >40 kg (36%). No data on reconstruction of arterial branch(es) for segment IV were provided. Biliary reconstruction was a duct-to-duct anastomosis in 24 cases (65%) and a hepaticojejunostomy in 13 (35%).

Outcome Analysis and Statistical Methods

Outcome was analyzed according to donor body weight (BW) (≤40 kg vs. >40 kg), recipient age (adults vs. pediatrics), and type of graft (LLS vs. ERG). Seventeen children received LLSs from donors ≤40 kg, 15 patients (9 adults and 6 children) received ERGs from donors ≤40 kg, 23 children received LLSs from donors >40 kg, and 24 patients (19 adults, 5 pediatrics) received ERGs from donors >40 kg. Postoperative mortality and retransplantation rates, patient and graft survival, and incidence of postoperative complications were analyzed and compared between categories. Vascular complications were distinguished as arterial (ACs), portal and outflow complications. Biliary complications (BCs) and surgical complications were considered as those requiring reoperation and/or interventional percutaneous or endoscopic treatment. Analysis of bacterial, viral, fungal, and protozoal infections was restricted to cases with clinical and microbiological evidence.

Results were expressed as mean ± SD and/or median and range. Differences between continuous variables were evaluated with the Mann-Whitney U test, while differences between categorical variables were calculated with the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test. Actuarial survival rates were computed with the Kaplan-Meier method, and the differences between groups were compared by the log-rank test. Survival was considered from the day of surgery to the day of death or retransplantation, or the last follow-up visit. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was carried out with the SPSS software packaging (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Donor and Recipient Profiles

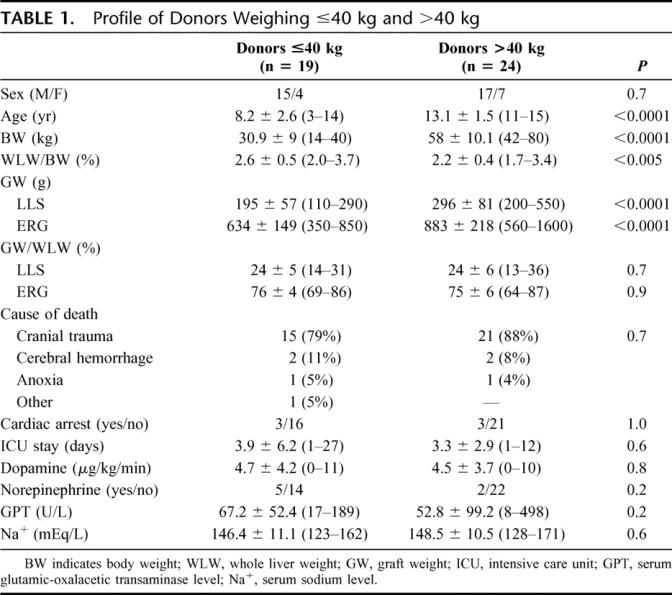

Profiles of donors ≤40 kg and >40 kg are shown in Table 1. The graft weight was available for 36 LLSs (90%) and 33 ERGs (85%). Mean age, BW, and mean graft weight of both LLSs and ERGs were significantly lower in donors ≤40 kg. The mean whole liver weight to BW ratio was significantly higher in donors ≤40 kg. In both categories, LLS and ERG represented approximately 25% and 75% of the whole liver mass, respectively. Causes of death, occurrence of cardiac arrest, length of stay in the ICU, use of vasopressors, serum GPT, and sodium levels did not differ between groups.

TABLE 1. Profile of Donors Weighing ≤40 kg and >40 kg

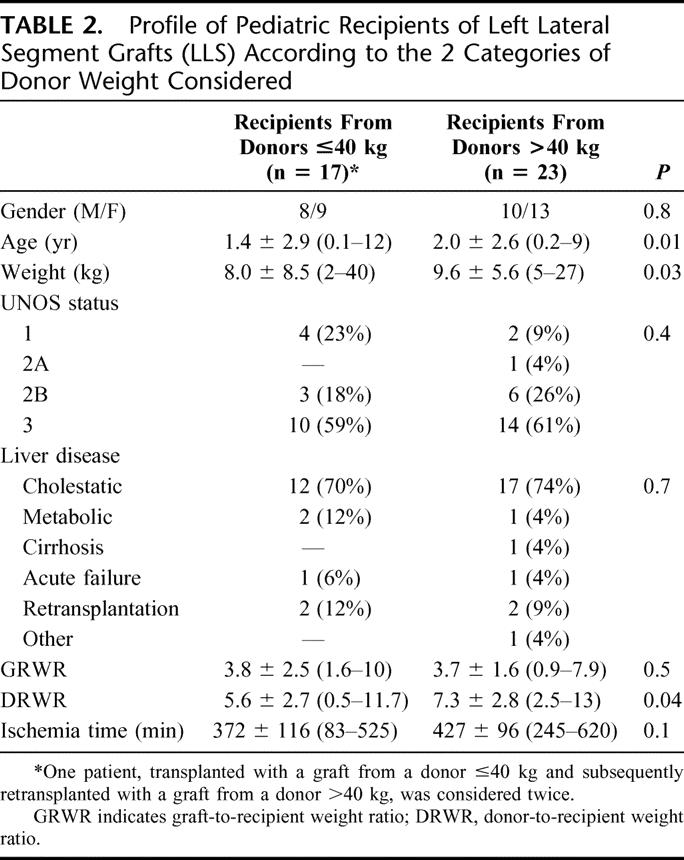

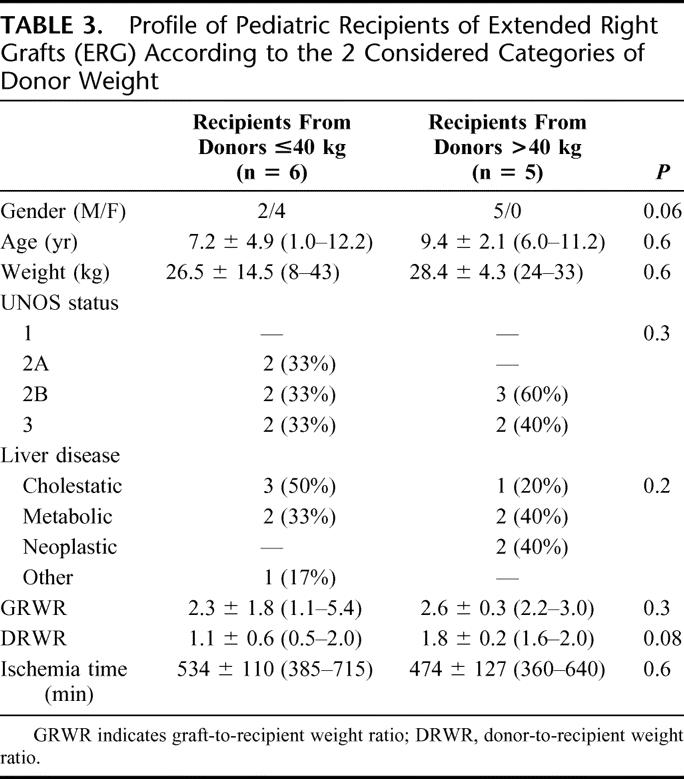

Demographic and clinical profiles of pediatric recipients of LLSs and ERGs, divided according to donor BW categories, are reported in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Mean BW, age, and DRWR were significantly lower in recipients from donors ≤40 kg among LLS recipients, while these differences were not statistically relevant in ERG recipients. In 4 patients receiving LLSs, the indication was failure of the primary transplant. One 12-year-old girl with biliary atresia had undergone a primary transplant with a whole liver graft from an adult donor. She subsequently experienced early HAT and received an LLS from an 8-year-old donor (BW = 20 kg). One 4-year-old boy with biliary atresia had received a primary transplant with an LLS from an adult donor. Three years later, he underwent retransplantation for chronic rejection with an LLS from an 8-year-old donor (BW = 40 kg). As reported above, a 1-month-old girl with neonatal hemochromatosis who developed subacute liver failure had a primary LLS transplant from an 11-year-old donor (BW = 35 kg). She subsequently developed chronic rejection and was retransplantated with an LLS from an 11-year-old donor (BW = 63 kg). A 9-month-old girl with biliary atresia had received a primary LLS from an adult donor. She developed early HAT and was retransplanted with an LLS from an 11-year-old donor (BW = 58 kg). Among all pediatric recipients, 9 patients (18%) were in very poor clinical condition (UNOS status 1 or 2A). Patients transplanted with ERGs had a significantly lower mean GRWR (2.4 ± 1.3 [1.1–5.4]) and mean DRWR (1.4 ± 0.6 [0.5–2.0]) than recipients of LLSs (3.8 ± 2.0 [0.9–10.0], P = 0.01, and 6.5 ± 2.8 [0.5–13.0], P < 0.0001, respectively).

TABLE 2. Profile of Pediatric Recipients of Left Lateral Segment Grafts (LLS) According to the 2 Categories of Donor Weight Considered

TABLE 3. Profile of Pediatric Recipients of Extended Right Grafts (ERG) According to the 2 Considered Categories of Donor Weight

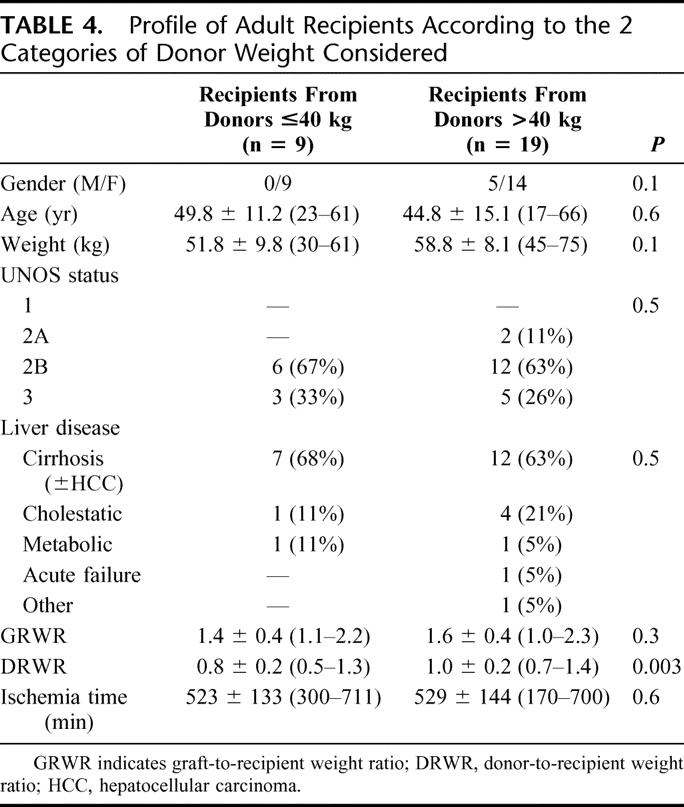

Adult patient profiles are shown in Table 4. DRWR was the only parameter significantly lower in patients with grafts from donors ≤40 kg.

TABLE 4. Profile of Adult Recipients According to the 2 Categories of Donor Weight Considered

Total ischemia time was longer in patients receiving ERGs than in those transplanted with LLSs (521 ± 130 minutes [170–715] vs. 403 ± 108 [83–620<], P < 0.0001).

Mortality and Retransplantation

At the end of the study, 67 patients (86%) were alive and 11 (14%) had died, 6 of 50 children (12%) and 5 of 28 adults (18%). Five deceased children received LLSs and one an ERG. Four patients died within the first postoperative month. A 15-month-old girl, weighing 9 kg and transplanted for intrahepatic arteriovenous fistulae with a 12-year-old LLS (donor BW = 70 kg), had primary graft nonfunction (PNF) and died on the 2nd postoperative day. An 11-month-old girl, weighing 6 kg, transplanted for Alagille's syndrome with a 5-year-old LLS (donor BW = 20 kg), had fatal hemorrhagic shock due to the rupture of the recipient common hepatic artery on the 5th postoperative day. A 9-year-old boy, transplanted for biliary atresia with a 12-year-old LLS (donor BW = 60 kg), experienced PNF and died on the 6th postoperative day. A 12-month-old boy, weighing 8 kg and suffering from biliary atresia, was transplanted with an ERG from a 3-year-old donor (BW = 14 kg). He was retransplanted due to HAT on the 4th postoperative day with an LLS from an adult donor, and died on the 7th postoperative day due to cerebral edema. One 2-month-old patient, weighing 5 kg, transplanted for acute liver failure of unknown etiology with a 10-year-old LLS (donor BW = 32 kg), developed irreversible neurologic damage and died 9 months after transplant with functioning graft. The already mentioned 1-month-old girl, weighing 3 kg, transplanted for neonatal hemochromatosis with an 11-year-old LLS (donor BW = 35 kg), was retransplantated 7 months later with an 11-year-old LLS (donor BW = 63 kg). The infant experienced cardiac arrest at graft reperfusion and died soon thereafter. Autopsy revealed severe cardiomyopathy caused by iron deposition due to the primary disease.

Two adult patients died within the 1st postoperative month and 3 others died thereafter. A 43-year-old woman with HCC and cirrhosis, transplanted with a graft from a 10-year-old donor (BW = 40 kg), died on the 4th postoperative day with functioning graft from pulmonary embolism. A 50-year-old woman, transplanted for HCV-related cirrhosis with an ERG from a 10-year-old donor (BW = 32 kg), died on the 13th postoperative day as a consequence of hepatic vein thrombosis. A 50-year-old woman, who underwent primary SLT for primary biliary cirrhosis from a 12-year-old donor (BW = 52 kg), developed HAT and was retransplanted with a whole liver graft from an adult donor 43 days after transplant; she eventually died due to sepsis on the 52nd postoperative day. A 55-year-old patient, transplanted for HCV-related cirrhosis from an 8-year-old donor (BW = 34 kg), died in the 10th postoperative month due to sepsis. Finally, a 47-year-old woman with HCV-related cirrhosis, transplanted from a 12-year-old donor (BW = 43 kg), died 20 months later with functioning graft from lung cancer.

At the end of the study, 6 patients (8%) had been retransplanted (4 children [8%] and 2 adults [7%]). Among the children, 2 had received LLSs and 2 ERGs. In addition to the patients already mentioned above, one 14-month-old child, weighing 7 kg, transplanted for biliary atresia with an LLS from a 9-year-old donor (BW = 34 kg), developed early HAT and underwent successful retransplantation on postoperative day 2 with an LLS from an adult donor. A 9-year-old patient with biliary atresia experienced late HAT of the first graft (ERG) procured from a 12-year-old donor (BW = 42 kg), and was successfully retransplanted in the 10th postoperative month with a whole liver graft from a 5-year-old donor. A 33-year-old patient, transplanted for fulminant hepatic failure of unknown origin with a 14-year-old graft (donor BW = 55 kg), was retransplanted due to intrahepatic bacterial infection on the 51st postoperative day, and is currently alive and well.

Patient and Graft Survival

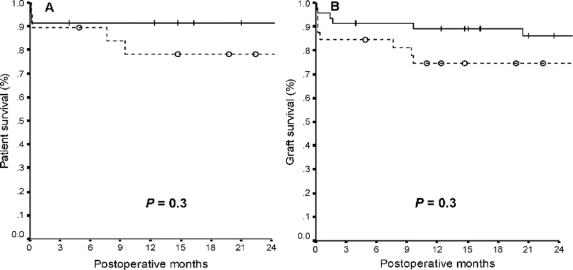

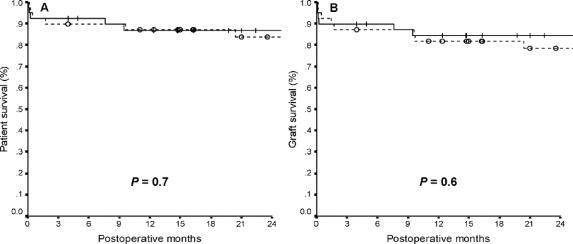

Median follow-up time was 28 months (range, 0.1–83 months). Overall 2-year patient and graft survival rates were 85% and 81%, respectively. Two-year patient and graft survival rates were 88% and 84% in children, and 81% and 77% in adults, respectively (P = 0.5). No significant differences were found in 2-year patient and graft survival rates between recipients from donors >40 kg and from donors ≤40 kg (Fig. 1), and between recipients of LLSs and of ERGs (Fig. 2). Among adult recipients, patient and graft survival rates were 67% and 67% in recipients from donors ≤40 kg, and 87% and 82% in recipients from donors >40 kg, respectively (P = 0.1).

FIGURE 1. Patient (A) and graft (B) survival rates after SLT from donors >40 kg (―) and ≤40 kg ( - - - ) of body weight (+ and ○ indicate censored patients).

FIGURE 2. Patient (A) and graft (B) survival rates after SLT with LLS (―) and ERG ( - - - ) (+ and ○ indicate censored patients).

Postoperative Complications

Vascular complications occurred in 8.9% of cases (5 arterial [6.3%], one portal [1.3%] and one outflow [1.3%]), BCs in 21.5% (9 strictures [11.4%] and 8 leaks [10.1%]), surgical complications in 15 cases (19%), and infections in 14 (17.7%). All vascular complications were thromboses or stenoses. No statistically significant differences were observed in the incidence of complications according to patient age, donor BW, and type of graft. Children showed less vascular, biliary, and surgical complications than adults (7.8% vs. 10.7%, 17.6% vs. 28.6%, and 15.7% vs. 25%, respectively). Infectious complications occurred in 17.6% of the children and in 17.9% of the adults. Vascular complications occurred in 12.5% of cases (ACs = 9.4%) with donors ≤40 kg and in 6.4% (ACs = 4.2%) with donors >40 kg. The same groups had 18.7% and 23.4% of BCs, 21.9% and 17% of surgical complications, 18.7% and 17% of infectious complications, respectively. A higher (but not statistically significant) rate of vascular complications and BCs were recorded in recipients of ERGs versus recipients of LLSs (12.8% [ACs = 10.2%] vs. 5% [ACs = 2.5%], and 25.6% vs. 17.5%, respectively). Patients transplanted with ERGs from donors ≤40 kg had the highest incidence of ACs and BCs (13.3% and 26.7%). Surgical complications occurred in 17.9% of the ERG recipients and in 20% of the LLS recipients, while infectious complications developed in 20.5% and 15%, respectively. As previously reported, 4 patients (3 children and 1 adult) required retransplantation due to HAT. An adult recipient with stenosis of the hepatic artery was successfully managed with stent positioning through angiography. No patient died or was retransplanted for causes directly correlated to BCs, which were managed by surgery in 7 cases (41%) and by interventional radiology in 10 (59%).

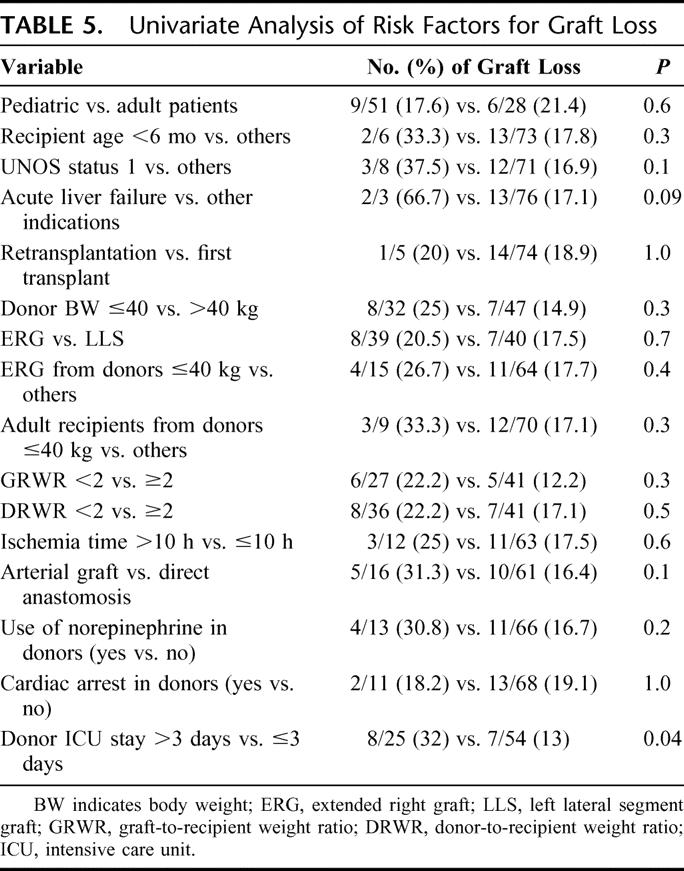

Risk Factors for Graft Loss and ACs

By univariate analysis, donor ICU stay >3 days was the only variable associated with increased risk of graft loss (P = 0.04). Acute hepatic failure as an indication for SLT reached only borderline significance (Table 5). The GRWR was available in 68 cases. The mean GRWR was 2.8 ± 1.7 (0.9–10) in surviving patients and 3.2 ± 2.9 (1.3–9.3) in patients who died after SLT (P = 0.7).

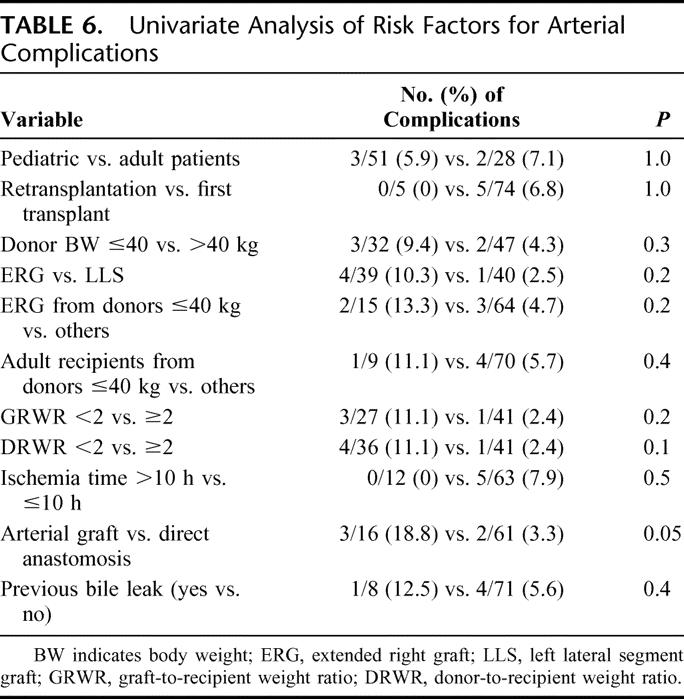

TABLE 5. Univariate Analysis of Risk Factors for Graft Loss

Among the known or supposed risk factors for ACs,24–29 patient age and donor BW, number of transplants, type of graft, GRWR, DRWR, ischemia time, type of arterial anastomosis, and previous occurrence of bile leaks were evaluated. None of the variables studied was significantly associated with AC; the only parameter showing even a borderline association was the use of interposition arterial conduits (P = 0.05) (Table 6). The use of an interposition graft was significantly more frequent with lower DRWR (1.6 ± 1.8 [0.5–7.8] vs. 4.5 ± 3.5 [0.5–13]; P = 0.003), but not with lower GRWR (2.1 ± 1.2 [1.1–5.4] vs. 3 ± 1.9 [0.9–10]; P = 0.1). ACs occurred in 3.3% of cases in which a direct anastomosis was performed versus 18.8% of cases in which an extension graft was used.

TABLE 6. Univariate Analysis of Risk Factors for Arterial Complications

DISCUSSION

The scarcity of cadaver donors has pushed transplant teams to explore innovative strategies to increase organ availability for liver transplantation. Conventional SLT has gained widespread acceptance as a safe method of generating 2 grafts, usually for one pediatric and one adult recipient. Although recent results have proved satisfactory as shown by single-center experiences,3–16 outcomes vary greatly from one center to another, and are often inferior to WLT or living-donor liver transplantation.3 One study conducted to compare the life expectancy of a large population of patients included in the U.S. Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients recently demonstrated the “societal” benefit of SLT, but also a higher probability of graft loss with SLT with respect to WLT.20 As a result, the mandatory application of SLT remains controversial and strongly affected by restrictive criteria of donor selection (young age, hemodynamic stability, normal liver on gross inspection and with normal function, and very short ICU stay).4,5,15,17,18,20 Within these commonly recognized limits, it was shown that the routine use of SLT might increase the number of grafts by 15%, and that by discarding a single one of these criteria could augment organ availability by 43%.18

The ideal donor age thresholds for splitting are not well defined, but many authors suggest that donors older than 45 to 50 years or younger than 10 years should not be considered.17,18,20 The lower limit is dictated by the donor BW, which should not be less than 40 to 45 kg.15,18 Although limited to an early outcome evaluation, we found that donors older than 50 can be safely used.19 In view of the difficulties in retrieving organs for recipients of very small size, we have also been considering pediatric donors for SLT, even those aged less than 10 years or with a BW lower than 40 kg. As yet, no report has been published specifically addressing the application of SLT to pediatric donors. Indeed, such a strategy should balance the optimal quality of the grafts with problems linked to vascular and biliary reconstructions, and with the potentially inadequate liver mass.

This multicenter study reports an experience of 43 splits performed from October 1997 to July 2004, and involving 15 transplant teams. The number of SLTs performed by Italian Centers up to December 2003 represented 16% of the entire activity of SLT in Italy throughout the same period. Almost all procedures were carried out in situ, this technique allowing maximization of organ sharing in Italy as well as in other countries.1,8,11

This study shows that the use of donors aged <15 years is safe (85% patient and 81% graft survival). The splitting of livers from donors between 11 and 15 years seems justified because their body size approaches that of an adult, as shown by our data on BW in this category.

Our analysis revealed that survival and complication rates were not significantly different between the 3 stratifications considered (donors ≤40 kg vs. >40 kg, adult vs. pediatric recipients, and recipients of LLSs vs. ERGs). Overall, they were similar to those reported in the largest single-center series of conventional SLT, without distinction between donor age categories,3–16 and to those obtained with other techniques (ie, cadaveric WLT and living-donor transplantation).11,16 Recipients from donors weighing ≤40 kg, adult recipients, and recipients of ERG had less favorable outcomes than recipients from donors >40 kg, pediatric recipients, and recipients of LLS, respectively. The low number of patients might not support definitive conclusions on a strategy of using grafts from donors ≤40 kg for adult recipients. The use of too small donors could be a possible explanation for these different outcomes. Dismal results have been reported when using pediatric whole grafts in adult patients,24–28 with an increased incidence of HAT, cholestasis and sepsis, and reduced survival in cases of inadequate dimensional matching.27,28

In our experience, the application of Urata's formula23 for estimation of whole liver weight, and the approximation of 25% and 75% of whole hepatic mass for LLSs and ERGs, respectively, were both correct as emerging from the actual graft weights, whereas GRWR remained above the safety limit of >1%21 in all cases. Interestingly, and again in accordance with previous findings,23 the GW/donor BW ratio was significantly higher in donors ≤40 kg versus >40 kg. These data confirmed that our criteria for donor/recipient size matching were appropriate, resulting in no occurrence of small-for-size syndromes. The proportionally higher liver mass in younger donors seems to be an argument in favor of a “downward” expansion of criteria of donor age. The problems relative to the small vasculature and biliary tract, rather than a low liver mass, seem responsible for the increased incidence of postoperative complications. Nevertheless, the graft loss was due to technical or graft dysfunction-related causes in 16% of recipients from donors ≤40 kg, in 13% of ERG recipients, in 11% of adult patients, and in 11% of adult recipients from donors ≤40 kg, with corresponding 2-year unrelated-death censored graft survival21 rates of 84%, 86%, 88%, and 88% in these categories.

Except for our early experience of transplanting a pediatric patient with an ERG from a 3-year-old donor, with subsequent retransplantation for HAT, the use of right-sided grafts from donors ≤40 kg in children appears reasonable. On the other hand, the slightly less than 80% graft survival rate in recipients of LLSs from donors ≤40 kg might have been adversely affected by the 25% of patients requiring urgent SLT, UNOS status 1 and 2A being recognized as negative prognostic factors.7 This experience confirmed that good donor selection is able to guarantee an excellent functional recovery in all paired grafts. Our selection criteria are slightly broader than those adopted by others.15–18

Donor ICU stay >3 days was the only factor able to predict graft loss by univariate analysis. However, we had only 2 cases of PNF (2.5%), whereas others reported PNF ranging from 4% to 8%17 or even higher than 10%.11,16 We observed an ischemia time significantly longer with ERGs than with LLSs. This could be explained by the fact that in 16% of cases both grafts were transplanted at the same center, in which the LLS transplant usually starts before ERG. Moreover, the back table of ERG is longer than LLS, given also the more frequent use of an arterial interposition graft. Apparently, this different ischemia time had no impact on the outcome, and especially on the incidence of PNF.

Concerning the separation of the hepatic vessels, the policy shared by the NITp Centers is to retain the celiac trunk with the LLS, which is dictated by the smaller caliber and possible multiplicity of the left hepatic artery. The overall incidence of vascular complications (9%) was almost entirely due to the ACs rate, lower in recipients of LLSs (2%) and higher in recipients of ERGs (10%), with an average of 6%. This complication was especially pronounced, as expected, in recipients of ERGs from donors ≤40 kg.

Which partial graft, right or left, should retain the celiac trunk remains controversial. Most groups demonstrated that by maintaining the entire length of the celiac axis in continuity with the right grafts organ sharing among centers is improved without worsening patient and graft outcomes.3,11,16,30 Other authors6,31 showed that maintenance of the celiac trunk with the left-sided allograft does not increase the overall incidence of HAT and avoids the need for a left hepatic artery microvascular anastomosis. The recent literature reports an incidence of vascular complications of around 10%.3–16 Transplant centers performing SLT with maintenance of the celiac axis with the ERG frequently had an incidence of vascular complications above 10% with the “disadvantaged” LLS, whereas our overall data are within the range of 3% to 15% more commonly observed.3–16 Although some caution is needed when evaluating the use of ERGs from very small pediatric donors, we think that the implementation of organ sharing probably remains the only fundamental issue favoring the preservation of the celiac trunk with right grafts.

Many surgical and nonsurgical risk factors for ACs have been previously elucidated.24–29 Compared with liver transplantation with adult donors, additional risk factors with pediatric grafts are the small diameter of vessels, the frequent use of cytomegalovirus-positive donors for cytomegalovirus-negative recipients, and the greater postoperative fluctuation of coagulative state of pediatric recipients.24–26 Dealing with partial and small-sized grafts, the low GRWR and the need for interposition arterial grafts seem to be critical variables.24–28 In particular, when transplanting pediatric livers into adult recipients, it has been argued that, even though the size discrepancy of vessels can be managed by a widening plasty or an interposition graft, the entire hepatic vascular bed and the arterial flow through it will not change, and might be very low with small-sized livers, especially with a significant portal flow.27 Among the available factors investigated in our study, univariate analysis showed that the use of an arterial interposition graft for arterial anastomosis was the only one associated with ACs. We found a correlation between low DRWR and the use of arterial grafts, whose use probably reflected either surgeon's choice or necessity due to a graft/recipient size discrepancy. However, neither DRWR nor GRWR was associated with ACs. Our findings are supported by considerable evidence from both pediatric and adult liver transplantation24–26,29 but are in contrast with observations that the use of interposition grafts may improve results of living-donor and pediatric liver transplantation.32,33

Furthermore, the small diameter of arteries of ERGs in our series could justify the more frequent use of arterial interposition grafts compared with adult-to-adult right lobe transplantation.

The incidence of BCs was 21%, higher than that usually reported in SLTs.3–16 However, otherwise excellent series of partial graft transplantation showed a BC rate of around 30%,34,35 whereas a BC rate of approximately 22% is reported in adult-to-adult right lobe living-donor transplantation.36 The reason for the discrepancy is probably due to the smaller size of pediatric grafts. BCs were more frequent, with prevalence of leaks (data not reported), in recipients of ERGs than in recipients of LLSs. LLS bile ducts were very small, and their vascularization might have been impaired despite the “in situ” division of the hilar plate. On the other hand, a jeopardized blood supply to segment IV might be responsible for the higher prevalence of leaks in recipients of ERGs. However, no graft was lost as a direct consequence of BCs, which shows the ability of experienced liver transplant centers to treat the most common technical challenge in SLT conservatively.

CONCLUSION

This multicenter experience shows that SLT with pediatric donors should be considered a valid tool in limiting the persisting organ shortage. These results are probably related to the implementation of a SLT program in the NITp area with involvement of all cooperating centers and with a large number of cases, leading to sharing of the learning curve. Both small pediatric and adult patients might benefit from this strategy, although the use of donors ≤40 kg in larger recipients remains debatable. In this particular setting of SLT, the policy of maintaining the celiac trunk with left-sided grafts seems acceptable, while the use of vascular interposition grafts should be avoided due to the increased risk of arterial thrombosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the following contributors to this multicenter study: Dr. Pietro Majno, Clinics of Visceral Surgery and Transplantation, University Hospitals of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland; Dr. Xavier Rogiers, Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, University Hospital Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; and Dr. Manuel Lopez Santamaria, Unit of Liver Transplantation, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain; as well as Wallis Marsh, MD, for reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Reprints: Marco Spada, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Abdominal Transplantation Unit, Istituto Mediterraneo per i Trapianti e Terapie ad Alta Specializzazione (IsMeTT), UPMC Italy, Via E. Tricomi, 1, 90127 Palermo, Italy. E-mail: mspada@ismett.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Renz JF, Emond JC, Yersiz H, et al. Split-liver transplantation in the United States: outcomes of a Nation survey. Ann Surg. 2004;239:172–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couinaud C. Le Foie, Etudes anatomiques et chirurgicales. Paris: Masson, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renz JF, Yersiz H, Reichert PR, et al. Split-liver transplantation: a review. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1323–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogiers X, Malago M, Gawad K, et al. In situ splitting of cadaveric livers: the ultimate expansion of a limited donor pool. Ann Surg. 1996;224:331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goss JA, Yersiz H, Shackleton CR, et al. In situ splitting of the cadaveric liver for transplantation. Transplantation. 1997;64:871–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rela M, Vougas V, Muiesan P, et al. Split liver transplantation: King's College Hospital experience. Ann Surg. 1998;227:282–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghobrial RM, Yersiz H, Farmer DG, et al. Predictors of survival after in vivo split liver transplantation: analysis of 110 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2000;232:312–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spada M, Gridelli B, Colledan M, et al. Extensive use of split liver for pediatric transplantation: a single center experience. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:415–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sauer IM, Pascher A, Steinmuller T, et al. Split liver and living donation: the Berlin experience. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:1459–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nashan B, Lueck R, Becker T, et al. Outcome of split liver transplantation using ex-situ or in-situ splits from cadaver donors [abstract]. Joint Meeting of the International Liver Transplantation Society, European Liver Transplantation Association, and Liver Intensive Care Group of Europe. Berlin, Germany, July 11–13, 2001. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:C94. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broering DC, Mueller L, Ganschow R, et al. Is there still a need for living-related liver transplantation in children? Ann Surg. 2001;234:713–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otte JB. History of split liver transplantation. In: Rogiers X, Bismuth H, Busuttil RW, et al, eds. Split Liver Transplantation: Theoretical and Practical Aspects. Steinkopff-Darmstadt: Springer, 2002:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deshpande RR, Bowles MJ, Vilca-Melendez H, et al. Results of split liver transplantation in children. Ann Surg. 2002;236:248–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gridelli B, Spada M, Petz W, et al. Split-liver transplantation eliminates the need for living-donor liver transplantation in children with end-stage cholestatic liver disease. Transplantation. 2003;75:1197–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noujaim HM, Gunson B, Mayer DA, et al. Worth continuing doing ex situ liver graft splitting? A single-center analysis. Am J Transpl. 2003;3:318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yersiz H, Renz JF, Farmer DG, et al. One hundred in situ split-liver transplantation: a single-center experience. Ann Surg. 2003;238:496–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emond JC, Freeman RB, Renz JF, et al. Optimizing the use of donated cadaver livers: analysis and policy development to increase the application of split-liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:863–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toso C, Ris F, Mentha G, et al. Potential impact of in situ liver splitting on the number of available grafts. Transplantation. 2002;74:222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petz W, Spada M, Sonzogni A, et al. Pediatric split liver transplantation using elderly donors. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merion RM, Rush SH, Dykstra DM, et al. Predicted lifetimes for adult and pediatric split liver versus adult whole liver transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1792–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiuchi T, Kasahara M, Uryuhara K, et al. Impact of graft size mismatching on graft prognosis in liver transplantation from living-donor. Transplantation. 1999;67:321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srinivasan P, Vilca-Melendez H, Muiesan P, et al. Liver transplantation with monosegments. Surgery. 1999;126:10–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Urata K, Kawasaki S, Matsunami H, et al. Calculation of child and adult standard volume for liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1995;21:1317–1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazzaferro V, Esquivel CO, Makowka L, et al. Hepatic artery thrombosis after pediatric liver transplantation: a medical or surgical event? Transplantation. 1989;47:971–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oh CK, Pelletier SJ, Sawyer RG, et al. Uni- and multi-variate analysis of risk factors for early and late hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;71:767–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pastacaldi S, Teixeira R, Montalto P, et al. Hepatic artery thrombosis after orthotopic liver transplantation: a review of nonsurgical causes. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yasutomi M, Harmsmen S, Innocenti F, et al. Outcome of pediatric donor livers in adult recipients. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:38–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emre S, Soejima Y, Altaca G, et al. Safety and risk of using pediatric donor livers in adult liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stange BJ, Glanemann M, Nuessler NC, et al. Hepatic artery thrombosis after adult liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:612–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noujaim HM, Gunson B, Mirza DF, et al. Ex situ preparation of left split-liver grafts with left vascular pedicle only: is it safe? A comparative single-center study. Transplantation. 2002;74:1386–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kilic M, Seu P, Goss JA. Maintenance of the celiac trunk with the left-sided liver allograft for in situ split-liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73:1252–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rela M, Muiesan P, Bhatnagar V, et al. Hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation in children under 5 years of age. Transplantation. 1996;61:1355–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcos A, Killackey M, Orloff MS, et al. Hepatic arterial reconstruction in 95 adult right lobe living-donor liver transplants: evolution of anastomotic technique. Liver Transpl. 2003;6:570–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sieders E, Peeters PM, TenVergert EM, et al. Analysis of survival and morbidity after pediatric liver transplantation with full-size and technical-variant grafts. Transplantation. 1999;68:471–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallot MA, Mathot M, Janssen M, et al. Long-term survival and late graft loss in pediatric liver transplant recipients: a 15-year single-center experience. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:615–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pascher A, Neuhaus P. Bile duct complications after liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2005;18:627–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]