Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the quality of reporting of surgical randomized controlled trials published in surgical and general medical journals using Jadad score, allocation concealment, and adherence to CONSORT guidelines and to identify factors associated with good quality.

Summary Background Data:

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide the best evidence about the relative effectiveness of different interventions. Improper methodology and reporting of RCTs can lead to erroneous conclusions about treatment effects, which may mislead decision-making in health care at all levels.

Methods:

Information was obtained on RCTs published in 6 general surgical and 4 general medical journals in the year 2003. The quality of reporting of RCTs was assessed under masked conditions using allocation concealment, Jadad score, and a CONSORT checklist devised for the purpose.

Results:

Of the 69 RCTs analyzed, only 37.7% had a Jadad score of ≥3, and only 13% of the trials clearly explained allocation concealment. The modified CONSORT score of surgical trials reported in medical journals was significantly higher than those reported in surgical journals (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001). Overall, the modified CONSORT score was higher in studies with higher author numbers (P = 0.03), multicenter studies (P = 0.002), and studies with a declared funding source (P = 0.022).

Conclusion:

The overall quality of reporting of surgical RCTs was suboptimal. There is a need for improving awareness of the CONSORT statement among authors, reviewers, and editors of surgical journals and better quality control measures for trial reporting and methodology.

We evaluated the reporting quality of surgical randomized controlled trials published in general surgical and medical journals. We show suboptimal quality of reporting as assessed by standard quality scores and the CONSORT guidelines. The low quality cannot be explained by limitations inherent in the scientific assessment of operative interventions.

Well-designed and properly executed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide the best evidence about the relative effectiveness of different interventions.1 The results of these trials can have a profound and immediate impact on patient care. Trials conducted with inadequate methodological approaches are associated with exaggerated treatment effects.2–4 Inadequate methodology may be due to several reasons: subversion of randomization resulting in biased allocation to comparison groups; unequal provision of care apart from the intervention under evaluation; biased assessment of outcomes and inadequate handling of dropouts and losses to follow-up.5 Results of such biased studies can mislead decision making in health care at all levels, from treatment decisions for an individual patient to formulation of national public health policies. There is strong evidence to indicate that the quality of reporting of RCTs in the medical literature is less than optimal.6,7 To overcome such problems, the Consolidated Standards for reporting of Trials (CONSORT) Group developed the CONSORT statement8 in 1996, which was followed by a revised version in 2001.7

At least 25 scales have been described for the evaluation of trial quality,9 among which the Jadad score is commonly used and has been validated using established methodologic procedures.10 Although several studies have evaluated the quality of RCTs published in medical journals,10–12 to date there have been none directed at general surgical literature published in general surgery journals.

The aim of this study was to assess the quality of reporting of published general surgical RCTs using a checklist based on the CONSORT statement (providing a modified CONSORT score), the Jadad score, and the criteria of allocation concealment alone. We aimed to evaluate differences in reporting quality between studies published in surgical and general medical journals. We also determined whether specific study characteristics such as the number of authors, single or multicenter, statistician/epidemiologist involvement, and funding source were associated with reporting quality.

METHODS

RCTs published during the year 2003 in 6 of the top 10 impact factor surgery journals [Annals of Surgery (AS), British Journal of Surgery (BJS), World Journal of Surgery (WJS), Journal of Surgery (JS), Journal of American College of Surgeons (JACS), and American Journal of Surgery (AJS)] and the 4 major general medical journals [British Medical Journal (BMJ), Lancet, Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA), and New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM)] were retrieved for assessment of the quality of reporting. The search strategy involved screening the titles and abstracts of all the manuscripts published in the above journals in 2003 for the key words “randomized controlled trial.” Studies were only included if they were truly randomized, involved human subjects, reported predominantly on clinical outcomes and were on “surgical” topics. Full reports were obtained for those studies that appeared to meet the criteria or where there was insufficient information in the title and abstract.

The citation impact factor for 2002 obtained from journal citation reports was used to help in choosing the above journals for the study. From the top 10 journals, we chose 6 for which the full text was available at the University of Sheffield library. The “instructions to authors” section of all the journals was accessed to find out whether the journals endorsed the CONSORT statement.

Specific descriptive characteristics for each article such as the number of authors, number of centers involved, involvement of a statistician/epidemiologist, source of funding (if any), and country of study were noted by one observer (Z.A.), who then masked the manuscripts for details such as journal, authors, and institution. Part of the methodology used to assess the quality of the RCT reports was similar to that described by Moher et al.11 The reporting of allocation concealment was assessed as adequate, inadequate, or unclear as previously described.2 The Jadad scale was used, which contains 2 questions each for randomization and masking and 1 question evaluating the reporting of withdrawals and dropouts. Each question entailed a yes or no response option. In total, 5 points were awarded, with a score of 3 or more indicating superior quality.10 Allocation concealment and Jadad score were assessed by one observer (S.P.B.). A checklist of 30 items concerning reporting and/or methodology was then prepared from the revised CONSORT guidelines1 published in 2001. The score for each item ranged from 1 (corresponding to no description of the item) to 3 (corresponding to adequate description and methodology). The CONSORT guidelines were studied and the definitions of each checklist item were discussed by the reviewers in detail. Each article was then assessed for every item on the checklist and scored independently by 2 observers (S.P.B. and R.T.), who also later arrived at a consensus score. The scores for the 30 items were added and a percentage score was calculated for each trial (as some items were non applicable and did not merit any score).

The data were collected on an excel spreadsheet and exported to SPSS (version 12.0 for Windows) for analysis. Initial presentations were descriptive, which included the median (interquartile range) Jadad and modified CONSORT scores of the individual journals and the specific characteristics of the studies. Comparisons were then made between the quality of the reports in medical and surgical journals, and the association between study characteristics (number of authors, single or multicenter, statistician/epidemiologist involvement, and funding source) and the modified CONSORT score (measured as greater or lesser than the median) was studied. Nonparametric tests were used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Of the 87 manuscripts that were initially retrieved from the 10 different journals (6 surgical and 4 general medical), 69 were eligible for inclusion in the study. The reasons for exclusion included previous reporting of study methodology/results (6), nonsurgical topics (5), not truly randomized (3), cluster randomized trials (1), trials with predominantly nonclinical outcomes (1), and studies reporting trial design only (1).

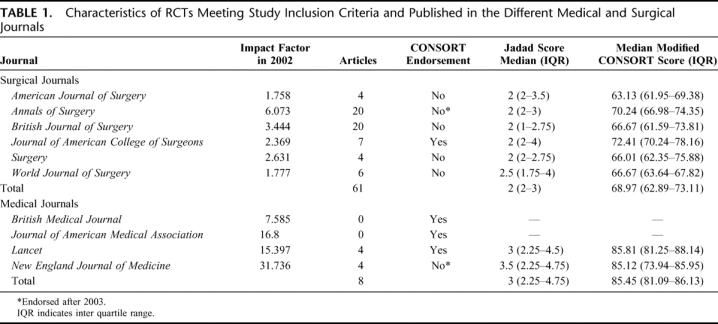

Table 1 shows the different journals along with their impact factor for 2002, number of articles analyzed, endorsement of the CONSORT statement in their “instructions to authors,” median Jadad score, and median modified CONSORT score calculated as percentage. The agreement between the pair of observers who independently assessed the RCTs using the CONSORT checklist was good (ICC = 0.85; 95% CI = 0.77–0.91; P < 0.001). Where there were initial disagreements, these were resolved and the consensus score was used for all further analyses. The 3 quality assessment tools used in this study (Jadad, allocation concealment, and the modified CONSORT score) correlated moderately with each other (Jadad and AC: Spearman's rho = 0.63; P < 0.001; Jadad and modified CONSORT: Spearman's rho = 0.66; P < 0.001; and AC and modified CONSORT: Spearman's rho = 0.68; P < 0.001).

TABLE 1. Characteristics of RCTs Meeting Study Inclusion Criteria and Published in the Different Medical and Surgical Journals

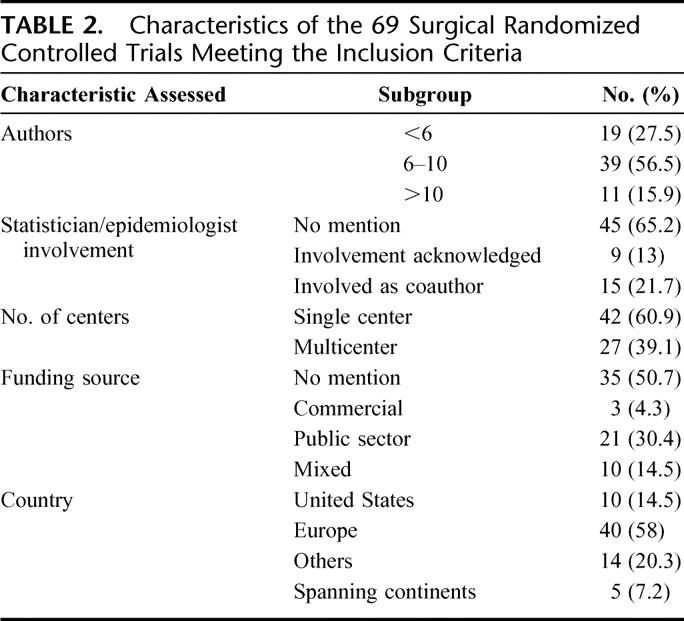

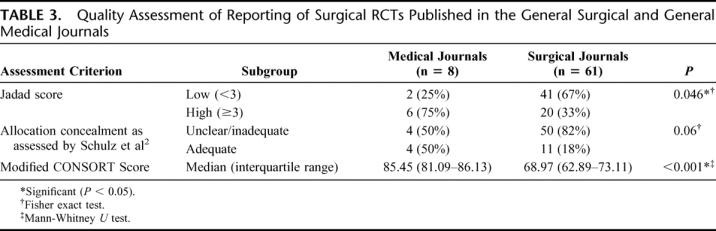

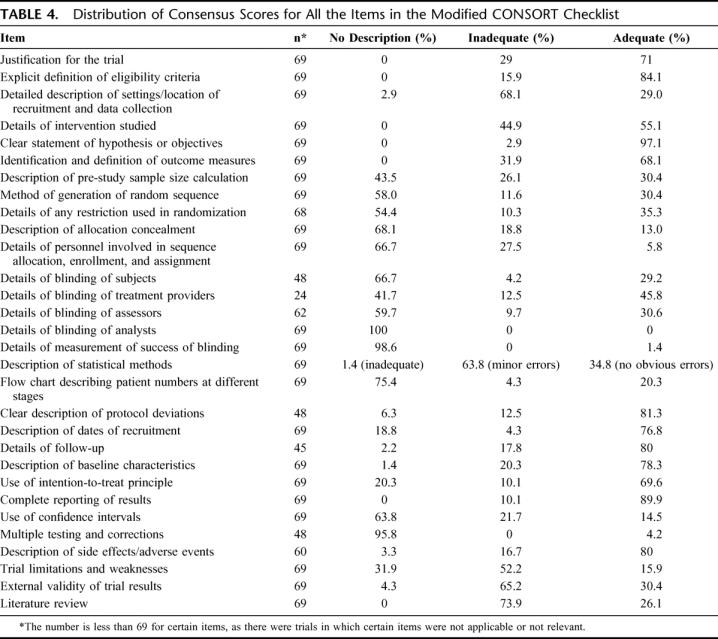

There was a good correlation between impact factor of the journals studied and median modified CONSORT score of the articles published in each of the journals (Spearman's rho = 0.75; P = 0.031). Table 2 shows the study characteristics (including the number of authors, involvement of statistician/epidemiologist, single or multicenter study, and funding source) of all the RCTs included in the analysis. Table 3 shows the quality as assessed by Jadad score, allocation concealment, and the CONSORT checklist for the RCTs published in the surgical and medical journals separately. Table 4 shows the distribution of scores on all the items on the CONSORT checklist.

TABLE 2. Characteristics of the 69 Surgical Randomized Controlled Trials Meeting the Inclusion Criteria

TABLE 3. Quality Assessment of Reporting of Surgical RCTs Published in the General Surgical and General Medical Journals

TABLE 4. Distribution of Consensus Scores for All the Items in the Modified CONSORT Checklist

Univariate analysis was carried out to determine the association of reporting quality (measured as greater or lesser than the median modified CONSORT score of 70) with author numbers, statistician/epidemiologist involvement, number of centers, and funding source. It was found that studies with higher author numbers (Mann-Whitney U test; z = −2.164; P = 0.03), multicenter studies (χ2 test with Yates correction; χ2 = 10.029; P = 0.002) and studies with a declared funding source (χ2 test with Yates correction; χ2 = 5.267; P = 0.022) were of significantly better quality. Involvement of a statistician/epidemiologist in the study also tended to be associated with better quality (χ2 test with Yates correction; χ2 = 2.271; P = 0.132).

DISCUSSION

“Surgical research or comic opera?” queried a Lancet editorial in 1996,13 stimulating a heated debate and serving to highlight the lack of RCTs in surgery and the limitations and difficulties of conducting one. Reports of RCTs should ideally convey relevant information to enable the reader to make an informed and a justified judgment concerning the validity of the trial and the effectiveness of the treatment.8 Furthermore, assessing the validity of the primary studies has been defined as one of the most important steps of the peer-review process.14

The need to improve the quality of reporting of RCTs has been highlighted in several specialties across healthcare.6,11,15,16 We performed an exploratory survey of the quality of reporting of surgical RCTs in the surgical literature and assessed similar studies published in general medical literature, which served as a comparator. We found that the quality of reporting of general surgical RCTs leaves considerable room for improvement. The quality of reporting in surgical journals was clearly inferior to the quality of reporting of surgical trials in medical journals as assessed by allocation concealment, Jadad score, and the modified CONSORT score (Table 3). We acknowledge that the impact factors of the medical journals evaluated are greater than the surgical ones (Table 2) and would therefore attract good quality trials. We have not hypothesized that the quality of trials in these 2 groups of journals would be the same, but have only used the trials in medical journals as a standard with which to compare the surgical ones. Of trials reported in medical and surgical journals, patient blinding was not feasible in 50% and 27.9%, respectively, and assessor blinding was not feasible in 12.5% and 9.8%, respectively. That blinding was not feasible in a greater percentage of the trials in medical journals indicates that difficulty in blinding cannot explain the low scores in the trials in surgical journals. Overall, high author numbers, multicenter studies, and declaration of funding source were factors found to be significantly associated with better reporting quality. This finding of significant associations of some study characteristics with better quality may well be spurious as unknown confounding factors (such as size of any available grants) could be responsible. There is evidence that inadequate reporting and/or methodology of key aspects affect the quality and usefulness of such studies. The majority of studies (58%) did not state the method of randomization (Table 4) and allocation concealment was adequately explained in only 13% of the studies. Proper randomization eliminates selection bias and is a crucial component of high-quality RCTs.17 Successful randomization hinges on 2 steps: generation of an unpredictable allocation sequence and concealment of this sequence from the investigator enrolling the participant (allocation concealment).9 The latter helps to prevent selection bias, protects the randomization sequence before and until the interventions are given to study participants, and can always be implemented. Trials that have not reported adequate allocation concealment have been found to be associated with exaggerated treatment effects.2 Potential difficulties associated with the application of RCTs to surgical problems include the difficulty in successfully blinding patients, investigators, and assessors, the variability of surgical techniques and operator skills, and the “learning curve,” which influences the efficacy of many interventions under study. Blinding of patients and assessors was not feasible in 30.4% and 10.1%, respectively, of all trials evaluated in this study. Of the trials in which blinding was possible, patient and assessor blinding were clearly reported only in 29.2% and 30.6%, respectively. Studies have shown that nonrandomized trials and RCTs that do not incorporate blinding are more likely to show advantages of a new intervention over the standard treatment.18 Trials that cannot be double blinded could still score 3 points on the Jadad scale if they included randomization (1 point), appropriate generation of randomization sequence (1 point), and a detailed account of withdrawals and dropouts (1 point). Furthermore, blinding can be achieved at levels other than participants and assessors, such as treatment providers, analysts, and reporters. Of all the analyzed trials, 43.5% had no description of prestudy sample size calculations and a further 26.1% described the parameters involved in the calculation of the sample size inadequately. Prestudy sample size calculations based on a clearly defined outcome are considered essential for both scientific and ethical reasons. Studies with small sample sizes are often inadequately powered to detect small but clinically significant differences between interventions and are therefore not a valid justification to negate the usefulness of the new treatments.19 “Intention-to-treat” analyses are usually favored over “per-protocol” analyses as they avoid bias associated with nonrandom loss of participants.20–22 Although such analyses may underestimate the real benefit of treatments for which noncompliance may be an issue, they address the effectiveness question that is the more pragmatic approach to the application of the interventions in clinical practice. Only 69.6% of the trials in our analyses clearly reported on intention-to-treat analyses and 81.3% described protocol deviations adequately. There is some evidence to suggest that trials that reported an intention-to-treat analysis and those that reported exclusions are associated with other aspects of good study design when compared with those that did not report on these aspects.23,24

The limitations of our study include the well-known difficulty of separately assessing methodology and reporting. Although many criteria, such as blinding, allocation concealment, recruitment, outcomes assessment, and statistical analysis, clearly fall within the domain of “methodology,” the design of our study necessitates the assessment of “study methodology” through the window of “reporting.” We acknowledge that space would have been a limiting factor for the inclusion of all information that we have used to assess reporting quality, but critical information with a bearing on scientific validity should always be prioritized. Although failure to report critical elements does not imply lack of implementation, we think that adequate reporting is vital for the credibility of a trial's conclusions. The attempted blinding of the reviewers to the journal, author, and institution names may not have been completely successful as the reviewers (who could be considered domain experts) had previously encountered some of the articles assessed and could have been prejudiced by preexisting knowledge on the subject. In addition, the CONSORT checklist contained items whose scoring was subjective and dependent on reviewers’ perceptions and domain knowledge. The assessment of the item of “allocation concealment” as part of the modified CONSORT checklist was slightly in variance with the assessment described by Schulz et al in 1995,2 which explains the difference in the scoring as shown in Tables 3 and 4.

Our findings suggest that the reporting quality of RCTs in general surgery falls well below the optimum and cannot be explained by potential limitations in the scientific assessment of operative interventions. We have recently demonstrated similar results in cardiothoracic literature and shown that authors of RCTs lack awareness of guidelines such as CONSORT.25 As results of RCTs have a significant impact on clinical decision-making, vigilance is required when relying on the results of these trials for implementing new treatments. The responsibility for improvement should primarily lie with the investigators, but reviewers and editors of surgical journals could facilitate the process by endorsing guidelines such as the CONSORT statement.

Footnotes

Reprints: Sabapathy P. Balasubramanian, FRCS Ed, Academic Unit of Surgical Oncology, K Floor, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, University of Sheffield, S10 2JF, UK. E-mail: s.p.balasubramanian@sheffield.ac.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, et al. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:663–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, et al. Empirical evidence of bias: dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995;273:408–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moher D. CONSORT: an evolving tool to help improve the quality of reports of randomized controlled trials. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials. JAMA. 1998;279:1489–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huwiler-Muntener K, Juni P, Junker C, et al. Quality of reporting of randomized trials as a measure of methodologic quality. JAMA. 2002;287:2801–2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Grimes DA, et al. Assessing the quality of randomization from reports of controlled trials published in obstetrics and gynecology journals. JAMA. 1994;272:125–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Lancet. 2001;357:1191–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276:637–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Jadad AR, Nichol G, et al. Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials: an annotated bibliography of scales and checklists. Control Clin Trials. 1995;16:62–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L. Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials: a comparative before-and-after evaluation. JAMA. 2001;285:1992–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Junker CA. Adherence to published standards of reporting: a comparison of placebo-controlled trials published in English or German. JAMA. 1998;280:247–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horton R. Surgical research or comic opera: questions, but few answers. Lancet. 1996;347:984–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kassirer JP, Campion EW. Peer review: crude and understudied, but indispensable. JAMA. 1994;272:96–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bath FJ, Owen VE, Bath PM. Quality of full and final publications reporting acute stroke trials: a systematic review. Stroke. 1998;29:2203–2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mills E, Loke YK, Wu P, et al. Determining the reporting quality of RCTs in clinical pharmacology. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;58:61–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jadad AR. Randomized Controlled Trials. London: BMJ, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimes DA. Randomized controlled trials: ‘it ain't necessarily so.’ Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:703–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altman DG, Bland JM. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ. 1995;311:485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YJ, Ellenberg JH, Hirtz DG, et al. Analysis of clinical trials by treatment actually received: is it really an option? Stat Med. 1991;10:1595–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lachin JL. Statistical considerations in the intent-to-treat principle. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21:167–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis JA, Machin D. Intention to treat–who should use ITT? Br J Cancer. 1993;68:647–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiz-Canela M, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, de Irala-Estevez J. Intention to treat analysis is related to methodological quality. BMJ. 2000;320:1007–1008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulz KF, Grimes DA, Altman DG, et al. Blinding and exclusions after allocation in randomized controlled trials: survey of published parallel group trials in obstetrics and gynaecology. BMJ. 1996;312:742–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiruvoipati R, Balasubramanian SP, Atturu G, et al. Improving the quality of reporting randomized controlled trials in cardiothoracic surgery: the way forward. J Thorac Cardio Surg. 2006. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]