Abstract

Background:

A pancreatic duct diameter (PDD) ranging from 4 to 5 mm is regarded as “normal.” The “large duct” form of chronic pancreatitis (CP) with a PDD >7 mm is considered a classic indication for drainage procedures. In contrast, in patients with so-called “small duct chronic pancreatitis” (SDP) with a PDD <3 mm extended resectional procedures and even, in terms of an “ultima ratio,” total pancreatectomy are suggested.

Methods:

Between 1992 and 2004, a total of 644 patients were operated on for CP. Forty-one prospectively evaluated patients with SDP underwent a new surgical technique aiming at drainage of the entire major PD (longitudinal “V-shaped excision” of the anterior aspect of the pancreas). Preoperative workup for imaging ductal anatomy included ERCP/MRCP, visualizing the PD throughout the entire gland. The interval between symptoms and therapeutic intervention varied from 12 to 120 months. Median follow-up was 83 months (range, 39–117 months). A pain score as well as a multidimensional psychometric quality-of-life questionnaire was used.

Results:

Hospital mortality was 0%. The perioperative (30 days) morbidity was 19.6%. Postoperative, radiologic imaging showed an excellent drainage of the entire gland and the PD in all but 1 patient. Global quality-of-life index increased in median by 54% (range, 37.5%–80%). Median pain score decreased by 95%. Twenty-seven patients (73%) had complete pain relief. Sixteen patients (43%) developed diabetes, while the exocrine pancreatic function was well preserved in 29 patients (78%).

Conclusion:

“V-shaped excision” of the anterior aspect of the pancreas is a secure and effective approach for SDP, achieving significant improvement in quality of life and pain relief, hereby sparing patients from unnecessary, extended resectional procedures. The deterioration of exocrine and endocrine pancreatic functions is comparable with that observed during the natural course of the disease.

In patients with “small duct chronic pancreatitis” with a pancreatic duct diameter <3 mm, extended resectional procedures and even total pancreatectomy are suggested. Forty-one prospectively evaluated patients with small duct chronic pancreatitis underwent a new surgical procedure (longitudinal “V-shaped excision” of the anterior aspect of the pancreas) aiming at creating an enlarged pancreatic ductal system. The operation proved to be safe and provided good pain relief and quality of life, therefore rendering it an alternative to major resectional procedures.

The heterogeneity of patient population and of symptoms as well as poor understanding of the pathophysiology in patients with CP are obstacles in the effectiveness of patient treatment. The symptom triad of chronic pancreatitis includes exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency and, representing the most important surgical indication, recurrent episodes of pain, which brings patients to their physicians and causes addiction to analgesics. In the past, 2 major reasons have been addressed advocating conservative treatment. The “historical” “burn-out” theory, advocating that pain will eventually subside as a consequence of the self-limiting pathophysiology of pancreatitis-related pain,1 has been challenged by more recent series, which report persistence of pain for more than 10 years.2 The second, emphasizing high morbidity and mortality rates associated with pancreatic operations, has become more or less obsolete as a result of significant progress in surgical and interventional techniques, especially in high-volume pancreatic centers. Therefore, conservative “watchful waiting” is nowadays hardly acceptable, especially if pancreatic pain has a morphologic basis.

Therapeutic options in conservative, interventional (endosonography-guided celiac plexus blockade), and surgical treatment of CP (including thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy) are mainly addressing pain relief. Based on the various hypotheses of pain origin in CP,3,4 (ductal) drainage and resection have become the 2 major principles for surgical treatment. Both options are combined in the principle of duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection and its various modifications.5–8

Apart from morphologic changes involving the glandular parenchyma, 2 anatomic variants of chronic pancreatitis can be distinguished with regard to the diameter of the main pancreatic duct, which is normally 4 to 5 mm.9 The large duct form, defined as main ductal diameter of >7 mm,10 has been considered the classic domain of drainage procedures.11–13 This so-called “large-duct chronic pancreatitis” is the typical feature of ductal irregularities presented by patients suffering from chronic pancreatitis (CP). Although conclusive, the argumentation that ductal dilatation causes ductal hypertension, hereby leading to pain, lacks evidence.

An extremely rare form of CP has been termed small duct pancreatitis, defined as main ductal diameter of ≤3 mm.9 This condition has been regarded as the domain of resectional procedures of various extents.14–19 Even total pancreatectomy as ultima ratio has been suggested. The therapeutic algorithm from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) in 1998, does not consider the option of draining procedures for these patients.20

To maintain as much pancreatic tissue as possible and to lower the risk of postoperative exocrine and endocrine pancreatic dysfunction, our group devised, in a previous study, a surgical technique of an organ-sparing operation, which consisted in a longitudinal V-shaped excision of the anterior aspect of the pancreas.21 Based now on more than 10 years of follow-up, here we report on long-term results regarding pain relief, improvement of quality of life, as well as exocrine and endocrine pancreatic functions in patients with SDP.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

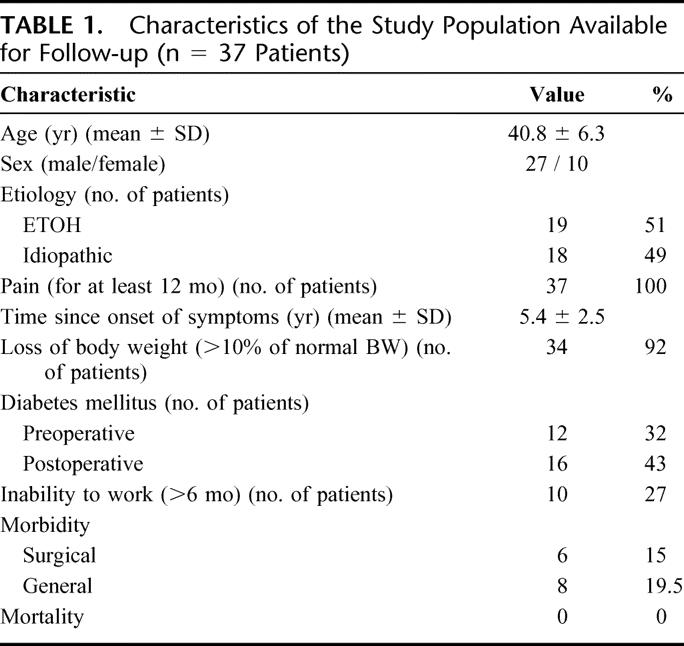

The ethical committee of the chamber of physicians in Hamburg approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before their inclusion in the study. Whereas data evaluation was performed prospectively, clinical evaluation was performed retrospectively. Between 1992 and 2004, 644 patients were operated on for treatment of CP. Among these, only 41 (6.37%) patients presented themselves with “small duct chronic pancreatitis.” Of these, 37 patients were available for follow-up (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Characteristics of the Study Population Available for Follow-up (n = 37 Patients)

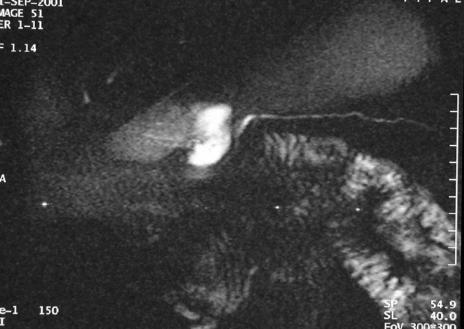

Whereas patients presenting with the more common form of “large-duct” chronic pancreatitis were excluded, only those with a pancreatic duct diameter ≤3 mm throughout the entire pancreatic gland (Fig. 1) were enrolled in this study. Diagnosis of CP was established when severe recurrent pain attacks with a pain history of more than 6 months as the mandatory criterion was associated with one of the following signs: pathomorphologic changes of the pancreatic parenchyma (fibrosis, calcifications, chronic pseudocyst, etc), inflammatory mass in the pancreatic head (>35 mm; optional, usually not found in SDP), coexistent complications of adjacent organs, eg, duodenal obstruction, common bile duct stenosis. These pathomorphologic changes of the pancreatic parenchyma were visualized either upon computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance tomography (MRT), while ductal pathology was assessed until 1998 by ERCP and from 1998 on by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Patient-related exclusion criteria were detection of a malignant pancreatic tumor, and coexisting malignancy of other organs.

FIGURE 1. RARE-sequence (rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement; TR 4500 milliseconds, TE 986, NSA 1, slice thickness 40 mm) of a preoperative pancreatic duct showing a narrowed duct with a maximal diameter of 1.14 mm.

The interval between symptom onset and therapeutic intervention varied between 12 months and 10 years (median, 55 months; mean ± SD, 65 ± 30 months). In the first 3 years after the onset of symptoms, 29 patients (71%) had been already hospitalized at least once in medical units and treated nonsurgically. Etiology was alcohol overindulgence in 22 patients. In the remaining 19 patients, etiology remained unknown, and pancreatitis was considered to be of idiopathic origin (Table 1).

Patient Assessment

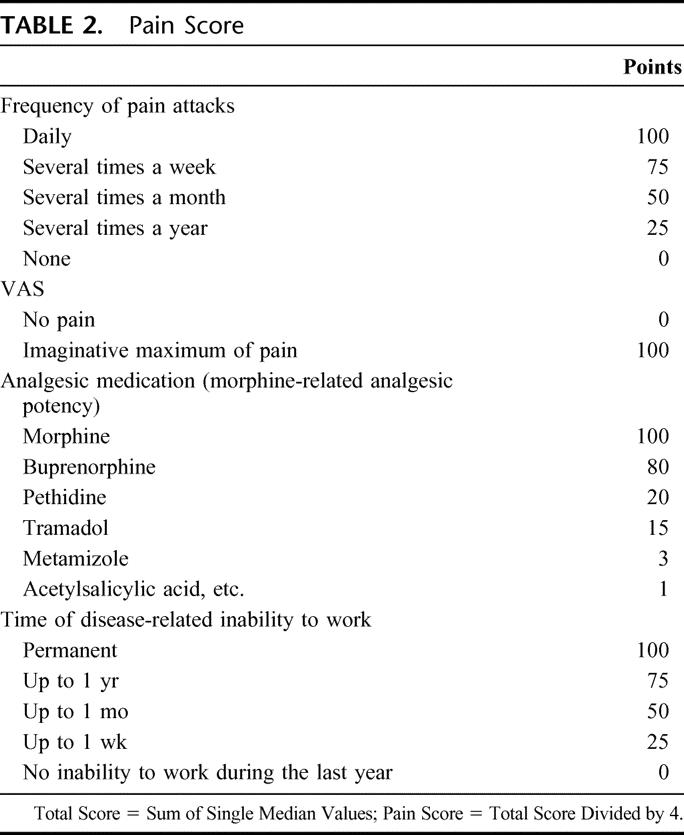

An established pain scoring system22 for detection of pain intensity as the primary target parameter included a visual pain analogue scale, frequency of pain attacks, analgesic medication as morphine equivalents, and time of disease-related inability to work (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Pain Score

Quality of life was measured by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer's quality-of-life questionnaire23 and an additional module of 20 specific items incorporating a disease-specific symptom scale, a treatment-strain scale, and an overall hope and confidence scale. This scoring system has previously been validated for patients with chronic pancreatitis.22 Further criteria were definitive control of complications arising from adjacent organs, mortality and morbidity rates, exocrine and endocrine pancreatic function, and occupational rehabilitation.24 Exocrine pancreatic function was assessed by detecting fecal chymotrypsin (normal >40 mg/g feces, pathologic <40 mg/g feces) and pancreolauryl test (normal >30%, intermediate 20%–30%, pathologic <20%18).

In all patients who were not on oral antidiabetic agents or insulin, an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed and the results were classified as normal or diabetes mellitus according to the criteria set forth by the German Diabetes Society in 200225 (based on WHO criteria of 1997). Diabetes mellitus was defined as blood glucose level of >200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) 2 hours after OGTT. Continuous alcohol consumption was defined as average daily consumption of >12 g alcohol.26,27

In addition, social and occupational rehabilitation, defined as return to regular daily professional or domestic activity, was assessed.

The family practitioner and the local administration were contacted for all patients that did not answer by mail to assess if the patient had died. Patients that were not retrieved by these methods were declared as “lost to follow-up.”

Surgical Technique of Longitudinal V-Shaped Excision

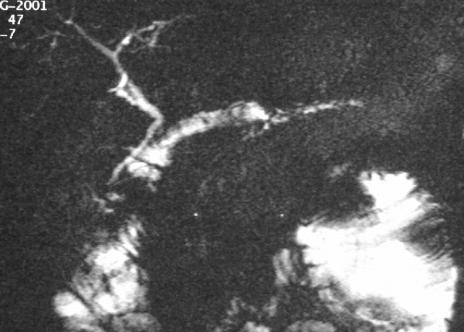

The surgical procedure consisted, as previously described,21 of exposure of the lesser sac, extensive Kocher maneuver, identification of the intrapancreatic course of the distal common bile duct, and longitudinal “V-shaped” excision of the ventral pancreatic aspect. The core difference to classic longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy (Partington-Rochelle procedure) is that V-shaped excision also drains pancreatic ducts of secondary and tertiary order. For reconstruction, a Roux-en-Y loop was used for creation of the anastomosis to the pancreas as a side-to-side pancreatojejunostomy using a single-layer monofilament running suture (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. Longitudinal V-shaped excision of the ventral pancreas for diffuse sclerosing pancreatitis with narrowing of the main pancreatic duct.

All patients were reassessed in the out-patient clinic at 6-month intervals. Follow-up ranged from 14 to 120 months with a median of 83 months (range, 39–117 months).

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis. Quality-of-life scores (functional and symptom scales) and pain scores were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test, and all other data were compared using the χ2 test. Statistical analysis was made on an intention- to-treat basis.

RESULTS

Whereas ERCP succeeded to visualize the PD only in 8 of 14 patients (57%), the introduction of MRCP in 1998 as the routine preoperative examination method resulted in correct visualization of the pancreatic ductal system in the rest of the 23 patients (100%). Operation failed in identifying the main PD in 8 patients (22%), 3 of them after the introduction of MRCP.

We had no hospital mortality. Two transient pancreatic fistulas, one of which was a secondary event after an intraluminal bleeding with partial disruption of the pancreatico-jejunal anastomosis, one bile leak after removal of the T-tube, as well as 3 wound infections accounted for a surgical hospital morbidity of 16.2% (Table 1). Only the patient with intraluminal bleeding had to be reoperated, one pancreatic fistula was managed conservatively, and the bile leakage was successfully treated by endoscopic stenting. Two patients had postoperative pneumonia. Mean operative time was 189 ± 69 minutes. Mean operative blood loss and mean number of transfused blood units were 490 ± 250 mL and 0.8 ± 1.8. In 22 (59%) patients, surgery was performed without need for blood transfusion at all. In 1 patient, who presented with an infected pseudocyst surrounding the spleen, the operation was combined with splenectomy.

Postoperative MRCP and parenchymatous MR presented an excellent drainage (Fig. 3) of the entire gland in all but 1 patient (22 of 23). In this 1 patient, where surgery failed to identify the main pancreatic duct, postoperative MRCP detected acceptable drainage of the pancreatic gland and the patient was free of symptoms 52 months after surgery.

FIGURE 3. Postoperative MR-sequence (RARE-sequence) in the same patient after V-shape excision showing the fluid along the duct within the jejunal loop.

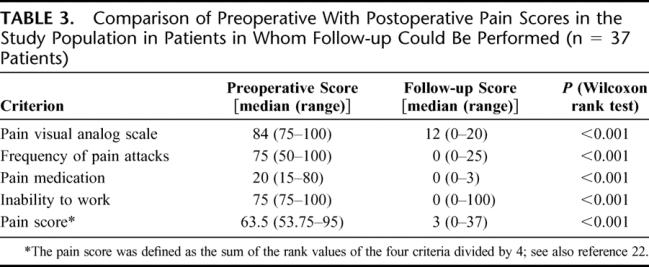

During follow-up complete relief of symptoms was observed in 33 patients (89%), and median pain score decreased by 95% (Table 3). Before surgery, the body weight loss exceeded 10% of the body weight in 34 patients (92%) with a mean loss of 8.2 ± 2.4 kg. Postoperatively, 29 patients (78.3%) gained more than 10% of their pretherapeutic body weight with a mean increase of 7.4 ± 2.8 kg, respectively. This increase of body weight was significantly better (P < 0.001) than that obtained in patients who had undergone classic resectional procedures (mean increase of 5.1 ± 3.6 kg) for treatment of CP (usually duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas according to Beger or Frey, but also in 24 patients classic Whipple resection and in 24 patients PPPD).

TABLE 3. Comparison of Preoperative With Postoperative Pain Scores in the Study Population in Patients in Whom Follow-up Could Be Performed (n = 37 Patients)

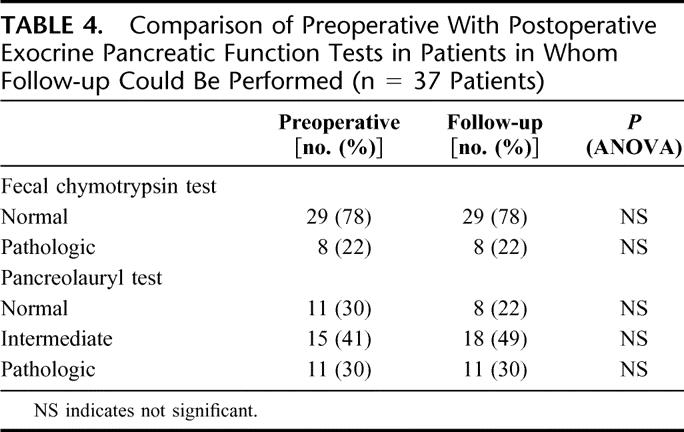

The preoperative exocrine pancreatic function assessed by fecal chymotrypsin concentration was normal in 29 patients (78%), and by pancreolauryl test normal or intermediate in 26 patients (71%). During follow-up, 3 patients (8%) with normal preoperative pancreatic function turned to intermediate values. In the remaining patients exocrine pancreatic function remained stable (Table 4). All patients with pathologic exocrine pancreatic function (11 patients; 30%) received a porcine pancreatic enzyme preparation (3 × 2 capsulae daily with 1000 IU protease, 18,000 IU amylase, and 20,000 IU triacylglycerol-lipase per capsula).

TABLE 4. Comparison of Preoperative With Postoperative Exocrine Pancreatic Function Tests in Patients in Whom Follow-up Could Be Performed (n = 37 Patients)

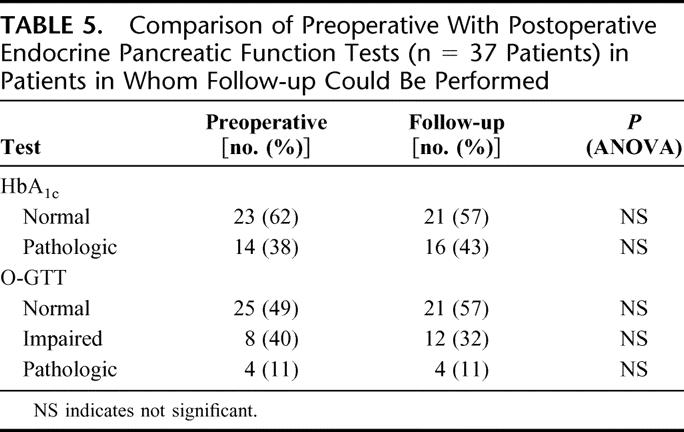

Before therapeutic intervention, 25 patients (68%) had normal oral glucose tolerance tests. 8 patients (21%) had an impaired oral glucose tolerance test and required oral antidiabetic agents. Four (11%) patients had insulin-dependent diabetes. Of the latter group, 3 remained postoperatively stable, while in 1 patient, diabetes deteriorated with increased need of insulin medication (additional 12 IU per day). Four patients with normal preoperative glucose tolerance turned to impaired glucose tolerance during follow-up, which gave us in total 16 (43%) patients with impaired endocrine pancreatic function (Table 5). Of the 4 patients who turned to impaired glucose tolerance postoperatively, only 1 had documented deterioration of endocrine function in the immediate postoperative course. In the remaining 3 patients, worsened endocrine insufficiency occurred 10, 19, and 27 months postoperatively.

TABLE 5. Comparison of Preoperative With Postoperative Endocrine Pancreatic Function Tests (n = 37 Patients) in Patients in Whom Follow-up Could Be Performed

Postoperatively, 4 patients admitted continued alcohol abuse according to the criteria defined by Lankisch et al.28 In another 2 patients, who did not acknowledge alcohol consumption, strong suspicion of continued drinking was based on communication with close relatives and referring physicians.

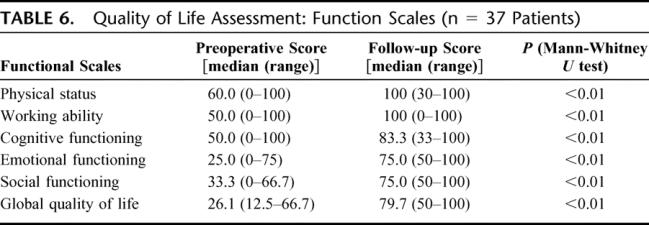

During the follow-up physical status, working ability, cognitive, emotional, and social functioning scores improved significantly by 40%, 50%, 33%, 50%, and 41.7%, respectively. The global quality-of-life index increased in median by 54% (range, 37.5%–80%; Table 6).

TABLE 6. Quality of Life Assessment: Function Scales (n = 37 Patients)

Thirty-one of 37 (84%) patients were unable to pursue with regular daily work for at least 6 weeks. After this initial period, 21 patients (57%) were professionally rehabilitated, 6 patients were unemployed (but job-seeking), 5 were retired, and 5 worked at home. Occupational rehabilitation after this initial period was observed in 27 (73%) patients.

DISCUSSION

Surgery and interventional endoscopy are nowadays regarded complementary therapy options for intractable pain in CP. Surgical procedures can be basically divided in 2 main arms: resectional and drainage procedures. A prerequisite for the suitability of endoscopic measures (eg, stenting, papillotomy, drainage of the pancreatic duct and pseudocysts) is the presence of a dilated pancreatic duct system. Therefore, the rare form of SDP which is characterized by a rather small diameter of the main pancreatic duct, or even, as in 19.6% of our population, vanishing of the main pancreatic duct should be treated by surgery.

Since the PD is in chronic small duct chronic pancreatitis buried throughout its entire length in fibrous and inflamed tissue, most specialists in the field of pancreatology and pancreatic surgery recommend for these patients extensive pancreatic resections.14–19,29,30 However, this ignores that (nonresectional) draining of the pancreatic duct by lateral pancreatojejunostomy has also been documented to result in effective pain relief in CP without ductal dilation.31,32 To explain this, it has been hypothesized that in CP without ductal dilation, pain might be the result of a noncompliant pancreas to expand during periods of elevated exocrine secretion and ductal volume.32 In line of this, it has been argued that the effect of lateral pancreatojejunostomy for CP with nondilated pancreatic ducts might be comparable to that of surgical decompression for compartment syndrome.33

Supposed this theory is true, decompression of a parenchymal compartment syndrome in patients with SDP may be achieved even with greater success by additional drainage of pancreatic ducts of second and third order. Hereby, the risk of restenosis of the pancreatojejunostomy, which is known to be one major reason for long-term treatment failure,33 may be reduced. To broaden the armament of surgical procedures in CP, therefore, we devised a customized operation for therapy for SDP. This longitudinal V-shaped excision of the anterior aspect of the pancreas allows sufficient drainage of secondary and tertiary pancreatic ducts, while at the same time preserving enough pancreatic tissue to maintain exocrine and endocrine function. As evidenced by postoperative MRCP and parenchymatous MR examinations, the operation led to an excellent drainage of the entire gland, main pancreatic duct, and secondary and tertiary pancreatic duct in all but 1 patient (22 of 23). In this 1 patient, where surgery failed to identify the main pancreatic duct, postoperative MRCP detected acceptable drainage of the pancreatic gland and the patient was free of symptoms 52 months after the operation. The procedure has been created on the basis of the Partington-Rochelle procedure12 and its modification of longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy combined with limited local excision of the pancreatic head as described by Frey.13 The new technique is also applicable in cases of Wirsungian duct “vanishing” as shown in 8 (22%) patients in this series.

To validate the success of our newly devised procedure, we have used standardized, psychometric tools.22 We were able to show that V-shaped longitudinal excision of the anterior aspect of the pancreas provides long-term pain relief and significant improvement of quality of life. During median follow-up of 83 months, recurrent pancreatitis occurred only in 1 patient requiring reoperation for an infected pseudocyst, which had developed at the pancreatic tail. V-shaped excision, as shown in this series, had comparable morbidity rates (surgical morbidity of 16%) as those reported by classic drainage procedures.10–13 What is also notable is that this morbidity rates seemed to be far lower as compared with those for patients who undergo classic resectional procedures for CP (surgical 30-day in-hospital morbidity of 16% vs. 24% after duodenum-preserving pancreas head resection-own data, data not yet published). The long-term follow-up of patients with small duct chronic pancreatitis showed that pancreatectomy of various extents as proposed by some authors14–19 may be substituted by our newly devised “longitudinal V-shaped excision of the anterior aspect of the pancreas,” which offers the benefit of resection without its burden.

Although only of subordinate value and therefore out of the surgical focus for the indication for surgery, the impairment of endocrine and exocrine function may be regarded to reflect the severity of CP. Since functional deterioration in patients in this series was seemingly “milder” as compared with changes characteristically found in CP including our own series,2,8,19,28 both histopathologic changes and patient history were carefully reevaluated for possible differences to chronic large duct pancreatitis. This comparison failed to evidence any difference between SDP and LDP. Overall, these findings render it, in the authors’ opinion, rather unlikely that SDP is not only a morphologic variant of CP as to ductal morphology but represents a completely different disease entity.

The cardinal success parameters for surgery in CP are long-lasting pain relief, significant improvement of quality of life, and reasonably low morbidity rates. V-shaped excision undoubtedly fulfilled these requirements. Also, it has to be emphasized that the procedure yields good preservation of exocrine function, hereby even resulting in considerable postoperative gain of body weight (7.4 kg). Although no randomized controlled trial exists which, with respect to the endocrine and exocrine impairment of the gland, has compared the natural course of the disease with that of patients after adequate (organ-preserving) surgery, our data seem to be in line with prospective studies10,29 showing that surgery may prevent further functional impairment, or even improves pancreatic endocrine and exocrine function.

Future trials have to show whether organ-preserving, longitudinal V-shaped excision of the anterior aspect of the pancreas should be limited only for patients with SDP or whether it could also be considered for patients in whom a dominant pathology of the pancreatic head causes secondary ductal dilation in the pancreatic body and tail.

Discussions

Dr. Ingemar Ihse: Chairmen, I am grateful to the Association for the opportunity of reading the manuscript and to comment on this paper by the Hamburg group. It is not more than 8 years since Dr. Izbicki described the V-shaped longitudinal excision of the ventral pancreas combined with pancreaticojejunostomy for treatment of pain in small duct chronic pancreatitis. The series of 13 patients showed good early results, but the mean follow-up was only 31 months in their paper published in 1998. Now they have collected and analyzed 37 patients and followed them up carefully for a median of 83 months. The long-lasting pain relief was excellent, and severe recurrent pain attacks were practically fully eliminated. Quality of life was also significantly improved. This is a descriptive study, but it is of clinical importance as these patients should now be recommended a less extensive operation instead of the major resections that, hitherto, have been practiced to achieve similar results.

My first question is about the severity of the chronic pancreatitis in these patients. The majority of them had normal exocrine and endocrine function preoperatively, in fact, 70% and 78%, respectively. This differs to what is normally seen in patients with dilated ducts and pancreatitis. In this context, it would be wise to also give the histopathologic analysis of the surgical specimens. One may wonder if small duct pancreatitis is a separate entity. Surprisingly, many of the patients were men with idiopathic etiology and, thus, no excessive alcohol consumption. I already mentioned their often normal pancreatic function. Again, what about the pathology report? Did it show any specific changes? Could this type of pancreatitis be part of another disease, such as cystic fibrosis, Sjögren's syndrome, or autoimmune pancreatitis? It would be interesting to hear you speculate about these thoughts. Is small duct chronic pancreatitis a separate entity?

In your manuscript, you used the term “ventral pancreas” in your title. Ventral pancreas, to me, corresponds to the ventral anlage of the gland, but you are not operating on the ventral anlage; you are operating on the ventral aspect of the pancreas. This may, perhaps, cause some confusion so you should correct it. Thank you.

Dr. Emre Yekebas: Thank you, Dr. Ihse, for these very insightful comments and questions. To begin with your last question, I think this is a misunderstanding. We are not talking about ventral pancreatitis but a ventral excision, a longitudinal ventral excision of the pancreas. Of course, pancreatitis was not focally localized only in the ventral aspects of the pancreas. Now, you spoke about the indication for surgery. Endocrine and exocrine insufficiency, which can be usually observed in these patients, does not represent the major indication in our institution, and I don't think in any other institution for surgical treatment of chronic pancreatitis. We know about some observational studies that have been performed in this regard and have reported protective effects in terms of an improvement of endocrine function. But still the main indication for surgery in chronic pancreatitis is pain, and this did not differ in these patients compared with the other patients who suffer from the usual and the more frequent large duct feature of chronic pancreatitis. We discussed also in our internal rounds several times the point whether or not the entity of small duct pancreatitis is only a radiologic entity or does represent, as you mentioned, really a completely different entity of patients. To be honest, I have to say that we are not sure. We have discussed this point, actually with our pathologists and, as you may know that Professor Guido Sauter came to Hamburg, we planned to perform some tissue microarrays in this respect to see whether there are different expressions of some markers in these patients compared with patients with “normal chronic pancreatitis,” but we are not sure.

Mr. Chris Russell: Thank you very much indeed for having the opportunity to discuss this paper with you, which I enjoyed enormously. From London, we described about 40 patients in 1992, under the name of Walsh in Gut, who reviewed patients, with what we called minimal change pancreatitis at that time. These patients had identical ducts to your own, but, interestingly, they were mainly female, and alcohol didn't play a part. Their only symptom was that of severe pain, which followed a very typical course to that of other patients with pancreatic disease. It was different from a similar group of those with sclerosing cholangiopancreatopathy or autoimmune pancreatitis, which have a different clinical course and pathologic changes. What I would really like to determine is the detailed histology. Our results were poor despite resection, even total pancreatectomies. These patients were often markedly dependent on analgesics by the time that we did the operation. I would like to know how dependent your group of patients were on analgesics by the time you operated. We changed our policy subsequent to this analysis and tended to manage them conservatively for several years. These patients after 20 years are still alive, often with bits of pancreas removed, but most of them, as a result of prolonged pancreatitis, have got no insulin secretion at all. So it does seem to be a progressive but not fatal disease. I would just like to know how you manage your patients afterward and whether any of them are developing further changes in the long term.

Dr. Emre Yekebas: Thank you very much for your questions. The ratio of female and male patients was identical as it was in patients who suffered from so-called large duct pancreatitis. That did not differ in our study population.

The histology, again, also did not differ. Until now, we did not perform immunohistologies, but it (conventional pathologies; authors comment) did not differ when it was reevaluated by our pathologists from the usual forms of pancreatitis. So, I cannot answer whether we are talking about histologically different features of pancreatitis. To be honest, I am not sure on this point.

Dependency of analgesics is, in our institution, as I mentioned earlier, the major indication for surgery, and this also did not differ when this entity of patients was compared with a much greater subset of patients that are usually operated on chronic pancreatitis.

And to answer your last question, we had 1 patient who had to be reoperated but not as a result of late morbidity. We have a total late morbidity rate in our patients who are screened for chronic pancreatitis of around 16%. In these patients, we had only 1 patient who had to be reoperated because of endoluminal bleeding during the hospital stay but no patient who had to be reoperated because of other problems (recurrence of disease or bile duct stenosis or something like that).

Dr. Norbert Senninger: Well, congratulations to you, Dr. Yebase and Dr. Izbicki for these nice results. I have a comment and 2 short questions. The comment is as to how this operation should be named. You are resecting something; you are minimizing the resection nevertheless, but it's not nonresectional. It's a euphemism, and you should correct that because I think the good results deserve a correct name.

Now, the question alludes to the time: how long will your good results last? You did not give us the time when the quality of life index was really taken. Was it taken after the patient was happily discharged from hospital? Was it after 6 months, perhaps after 3 years? We do know that we have problems with these operations, the long-term sequelae of the operation and the disease.

The second point is that you are hypothesizing, by doing what you are doing; you are causing less parenchymal loss of the pancreas, less diabetes, and so forth. Other than decompressing the compartment, which is definitely, I think, the valid point, did you really measure the diabetes? When resecting a big area of the pancreas, and just assuming that you are causing a depth of necrosis of 1 to 2 mm, if you add it up, it is in the end a considerable amount of volume. This may almost represent, let's say, at least a resectional treatment. Thank you very much for your presentation.

Dr. Emre Yekebas: Thank you very much for these comments and questions. First of all, we discussed also the question as to how to name this procedure repeatedly in our rounds. As you know maybe better than me, the question of whether a resectional procedure is performed or an excisional or draining procedure, the name is often used and applied quite artificially and you can name this a nonresectional excision, you can also name this an extended drainage procedure. It's an excisional procedure; you are right on this.

The second point: quality of life. This evaluation is performed every 6 months. We have a study secretary who sends quality of life questionnaires to the patients.

And the third question: as to the incidence of diabetes, we had a worsening of diabetes in 4 patients and this amounted to near 50% of patients who had diabetes in the whole cohort, which is hardly different from the other patients who suffer from chronic pancreatitis. The major problem that these patients have in our experience is the exocrine insufficiency.

Dr. Sergio Pedrazzoli: This is a resectional procedure. You resect 30% to 40% of the pancreas, and these are small pancreases. You have young people usually; you have people with pain but normal endocrine and exocrine secretion. You compare your procedure with resectional procedures like a left pancreatectomy or Frey's procedure, a 95% resection, or with a total pancreatectomy. However, I believe that this is not the real target against which to compare your procedure. I believe that in these patients you can do something else, like the Dean Warren procedure that preserves the body and tail of the pancreas within the bowel. With this procedure, you preserve pancreatic function and you also denervate the pancreas so that also the pain is better controlled with this procedure. Also, with respect to resection, I believe that you are a very high-volume center: the numbers are clear. We would be very grateful if you would give us a comparison of these 2 procedures: your procedure and the Dean Warren procedure.

Dr. Emre Yekebas: Thank you very much. I think the major problem in making any comparison in these patients is that we have not enough. I doubt that, even if we performed a randomized study, including many centers, that we would be able to provide a sufficient number of patients to undertake any comparative randomized trial; that is the problem. Of course, it should be compared particularly with resectional procedures because this is still, as far as I know, the official suggestion of, for example, the AGA. The AGA suggests that these patients who suffer from this disease should be resected, but the problem is how to get a sufficient number.

Dr. John Howard: I understood you to say that you did a pancreaticojejunostomy as part of your procedure, right?

Dr. Emre Yekebas: Yes.

Dr. John Howard: Have you had long-term operative or ERCP follow-ups? There is very little in the literature on long-term anatomic results. I've seen where we had anastomosed jejunum to pancreas but not to duct, re-explored years later showed the jejunum was 3 to 4 inches away from the pancreas, no connection at all.

Dr. Emre Yekebas: We did not perform ERCPs routinely, but as I already showed during my short presentation, we rather did MRCPs in some selected cases.

Footnotes

Reprints: Jakob R. Izbicki, MD, Department of Surgery, University Hospital Eppendorf, University of Hamburg, Martinistrasse 52, 20251 Hamburg, Germany. E-mail: izbicki@uke.uni-hamburg.de.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ammann RW, Akovbiantz A, Largiader F, et al. Course and outcome of chronic pancreatitis: longitudinal study of a mixed medical-surgical series of 245 patients. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:820–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lankisch PG. Natural course of chronic pancreatitis [Review]. Pancreatology. 2001;1:3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bockmann DE, Buechler M, Malfertheimer P, et al. Analysis of nerves in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:1459–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebbehoj N, Svendsen LB, Madsen P. Pancreatic tissue pressure in chronic obstructive pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1984;19:1066–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beger HG, Witte C, Krautzberger W, et al. Experiences with duodenum-sparing pancreas head resection in chronic pancreatitis. Chirurg. 1980;51:303–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strate T, Bloechle C, Busch C, et al. Modifications of the duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection. Ann Ital Chir. 2000;71:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frey CF, Smith GJ. Description and rationale of a new operation for chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1987;2:701–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izbicki JR, Yekebas EF. Chronic pancreatitis: lessons learned. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1185–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markowitz JS, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL. Failure of symptomatic relief after pancreaticojejunal decompression for chronic pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1994;129:374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nealon WH, Thompson JC. Progressive loss of pancreatic function in chronic pancreatitis is delayed by main pancreatic duct decompression. Ann Surg. 1993;217:458–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puestow CB, Gillesby WJ. Retrograde surgical drainage of pancreas for chronic pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1958;76:898–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Partington PF, Rochelle RE. Modified Puestow procedure for retrograde drainage of the pancreatic duct. Ann Surg. 1960;152:1037–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawyer R, Frey CF. Is there still a role for distal pancreatectomy in surgery for chronic pancreatitis? Am J Surg. 1994;168:6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Traverso LW, Longmire WP. Preservation of the pylorus in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;146:959–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saeger HD, Schwall G, Trede M. Standard Whipple in chronic pancreatitis. In: Beger HG, Buechler M, Malfertheimer P, eds. Standards in Pancreatic Surgery. Berlin: Springer, 1993:385–391. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossi RL, Rothschild J, Braasch JW, et al. Pancreatoduodenectomy in the management of chronic pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1987;122:416–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frey CF, Child CG, Fry W. Pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1976;184:403–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braasch JW, Vito L, Nugent FW. Total pancreatectomy for end-stage chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1978;188:317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izbicki JR, Bloechle C, Knoefel WT, et al. Duodenum preserving resections of the head of the pancreas in chronic pancreatitis: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1995;221:350–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warshaw AL, Banks PA, Fernandez-del Castillo C. AGA technical review: treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izbicki JR, Bloechle C, Broering DC, et al. Longitudinal V-Shaped excision of the ventral pancreas for Small Duct Disease in severe chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1998;227:213–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bloechle C, Izbicki JR, Knoefel WT, et al. Quality of life in chronic pancreatitis: results after duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas. Pancreas. 1995;11:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frey CF, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ, et al. A plea for uniform reporting of patient outcome in chronic pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1996;131:233–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brueckel J, Koebberling J. Definition, Klassifikation und Diagnostik des Diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Stoffwechsel. 2002;11(suppl 2):6–39. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukamal KJ, Rimm EB. Alcohol's effect on the risk for coronary heart disease. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:255–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klatsky AL. Moderate drinking and reduced risk of heart disease. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23:15–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lankisch PG, Happe-Loehr A, Otto J, et al. Natural course in chronic pancreatitis. Digestion. 1993;54:148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buechler M, Friess H, Mueller MW, et al. Randomized trial of duodenum preserving pancreatic head resection versus pylorus preserving Whipple in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1995;169:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whipple AO. Radical surgery for certain cases of pancreatic fibrosis associated with calcareous deposits. Ann Surg. 1946;124:991–1006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jalleh RP, Aslam M, Williamson R. Pancreatic tissue and ductal pressures in chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1235–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebbehoj N, Borly L, Bulowe J, et al. Evaluation of pancreatic tissue fluid pressure and pain in chronic pancreatitis: a longitudinal study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:462–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delcore R, Rodriguez FJ, Thomas JH, et al. The role of pancreatojejunostomy in patients without dilated pancreatic ducts. Am J Surg. 1994;168:598–601; discussion 601–602. [DOI] [PubMed]