Abstract

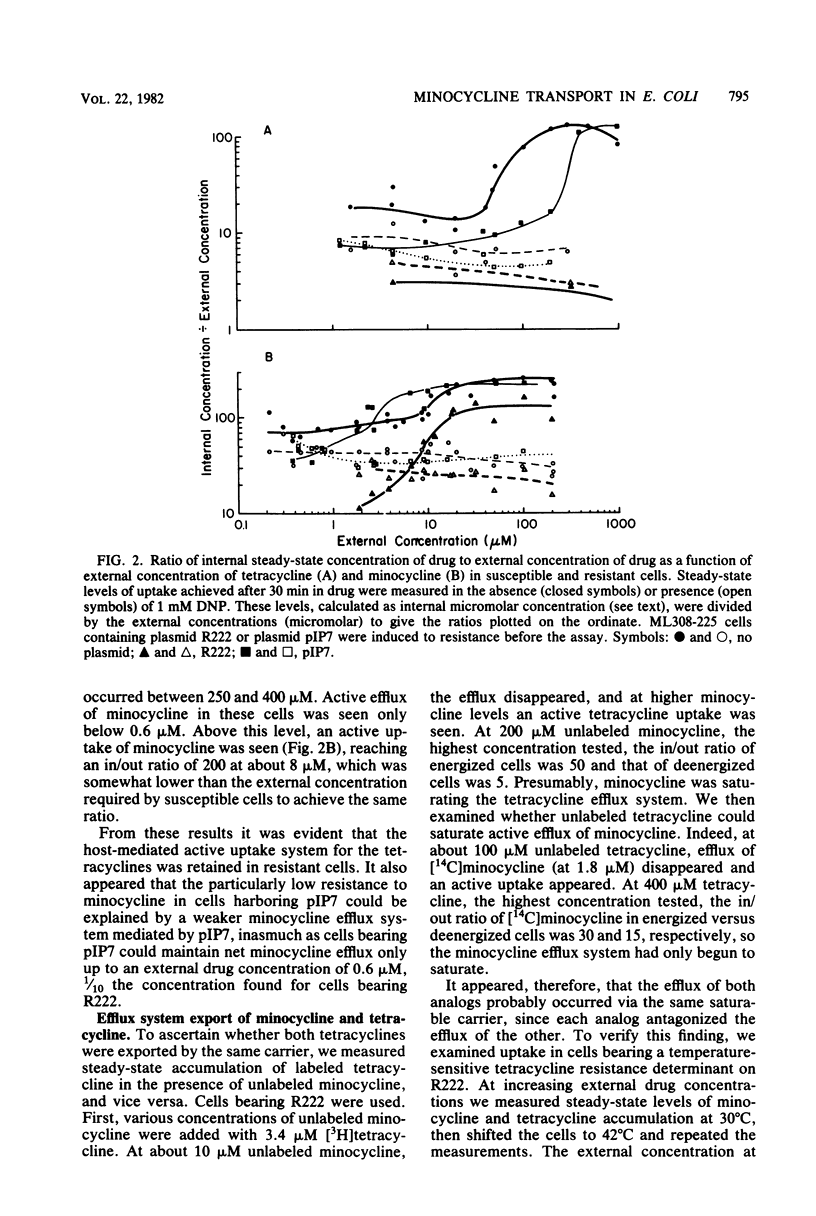

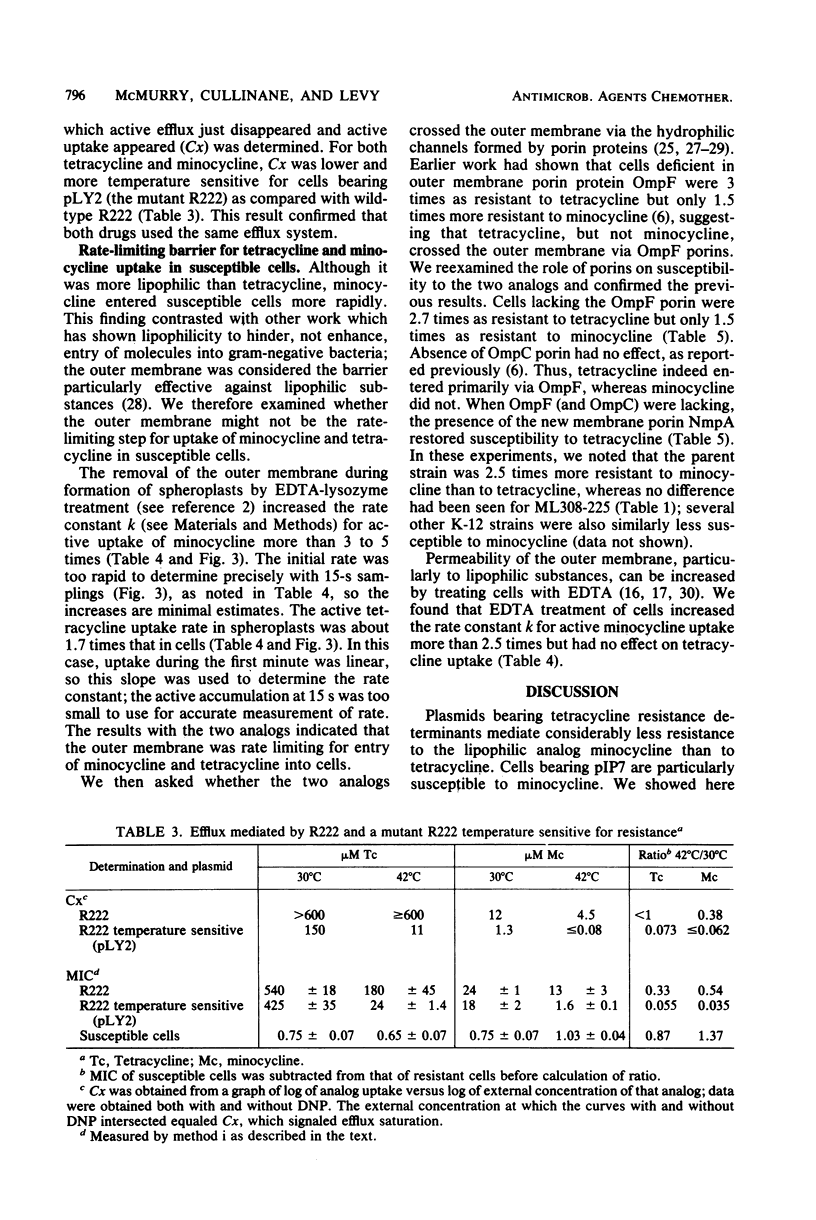

Plasmids which specify resistance to tetracycline offer much less resistance to its more lipophilic analog, minocycline. Resistance to minocycline varies for different plasmids. In the case of plasmid R222 (bearing the class B tetracycline resistance determinant on Tn10), minocycline resistance is comparatively high (10 microgram/ml, or 6% of the tetracycline resistance level). For plasmid pIP7 (bearing the class A determinant), minocycline resistance is only 1% of the tetracycline resistance level. To understand the basis for these differences, we compared the transport of the two tetracyclines by susceptible cells and by resistant cells. Uptake of minocycline by susceptible cells was 10 to 20 times more rapid than uptake of tetracycline and occurred largely via an energy-dependent route. This host-mediated energy-dependent uptake of both analogs was still present in tetracycline-resistant cells. In resistant cells, the same plasmid-mediated active efflux system previously described for tetracycline also exported minocycline. The 15-fold greater susceptibility of tetracycline-resistant R222-bearing cells to minocycline as compared with tetracycline could be explained at least in part by the more rapid influx of minocycline, which more easily overcame the efflux system. The particularly low minocycline resistance offered by pIP7 was due to a weak efflux for minocycline, 10-fold less effective than that mediated by R222. The rate-limiting step for uptake of both analogs appeared to be the outer membrane. That the lipophilic minocycline should cross this membrane more rapidly than tetracycline stands in contrast with other studies which show the outer membrane to be a barrier for entry of lipophilic substances.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ball P. R., Chopra I., Eccles S. J. Accumulation of tetracyclines by Escherichia coli K-12. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977 Aug 22;77(4):1500–1507. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(77)80148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birdsell D. C., Cota-Robles E. H. Production and ultrastructure of lysozyme and ethylenediaminetetraacetate-lysozyme spheroplasts of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1967 Jan;93(1):427–437. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.1.427-437.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. R., Ireland D. S. Structural requirements for tetracycline activity. Adv Pharmacol Chemother. 1978;15:161–202. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60483-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai T. J., Foulds J. Escherichia coli K-12 tolF mutants: alterations in protein composition of the outer membrane. J Bacteriol. 1977 May;130(2):781–786. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.2.781-786.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra I., Eccles S. J. Diffusion of tetracycline across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli K-12: involvement of protein Ia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978 Jul 28;83(2):550–557. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra I., Shales S., Ball P. Tetracycline resistance determinants from groups A to D vary in their ability to confer decreased accumulation of tetracycline derivatives by Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1982 Apr;128(4):689–692. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-4-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curiale M. S., Levy S. B. Two complementation groups mediate tetracycline resistance determined by Tn10. J Bacteriol. 1982 Jul;151(1):209–215. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.209-215.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bene V. E., Rogers M. Comparison of tetracycline and minocyclie transport in Escherichia Coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1975 Jun;7(6):801–806. doi: 10.1128/aac.7.6.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dürckheimer W. Tetracyclines: chemistry, biochemistry, and structure-activity relations. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1975 Nov;14(11):721–734. doi: 10.1002/anie.197507211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds J., Chai T. J. New major outer membrane proteins found in an Escherichia coli tolF mutant resistant to bacteriophage TuIb. J Bacteriol. 1978 Mar;133(3):1478–1483. doi: 10.1128/jb.133.3.1478-1483.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds J., Chai T. Isolation and characterization of isogenic E. coli strains with alterations in the level of one or more major outer membrane proteins. Can J Microbiol. 1979 Mar;25(3):423–427. doi: 10.1139/m79-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaki K., Kiuchi K., Arima K. Specificity and mechanism of tetracycline resistance in a multiple drug resistant strain of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1966 Feb;91(2):628–633. doi: 10.1128/jb.91.2.628-633.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarolmen H., Hewel D., Kain E. Activity of minocycline against R factor-carrying enterobacteriaceae. Infect Immun. 1970 Apr;1(4):321–326. doi: 10.1128/iai.1.4.321-326.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuck N. A., Forbes M. Uptake of minocycline and tetracycline by tetracycline-susceptible and -resistant bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1973 Jun;3(6):662–664. doi: 10.1128/aac.3.6.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leive L. Studies on the permeability change produced in coliform bacteria by ethylenediaminetetraacetate. J Biol Chem. 1968 May 10;243(9):2373–2380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leive L. The barrier function of the gram-negative envelope. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974 May 10;235(0):109–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb43261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S. B., McMurry L. Plasmid-determined tetracycline resistance involves new transport systems for tetracycline. Nature. 1978 Nov 2;276(5683):90–92. doi: 10.1038/276090a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurry L. M., Cullinane J. C., Petrucci R. E., Jr, Levy S. B. Active uptake of tetracycline by membrane vesicles from susceptible Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981 Sep;20(3):307–313. doi: 10.1128/aac.20.3.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurry L., Levy S. B. Two transport systems for tetracycline in sensitive Escherichia coli: critical role for an initial rapid uptake system insensitive to energy inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978 Aug;14(2):201–209. doi: 10.1128/aac.14.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurry L., Petrucci R. E., Jr, Levy S. B. Active efflux of tetracycline encoded by four genetically different tetracycline resistance determinants in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Jul;77(7):3974–3977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez B., Tachibana C., Levy S. B. Heterogeneity of tetracycline resistance determinants. Plasmid. 1980 Mar;3(2):99–108. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(80)90101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. H., Smith H. L., Rock W. L., Hedberg S. Antibacterial structure-activity relationships obtained with resistant microorganisms I: Inhibition of R-factor resistant Escherichia coli by tetracyclines. J Pharm Sci. 1977 Jan;66(1):88–92. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600660122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakae T. Identification of the outer membrane protein of E. coli that produces transmembrane channels in reconstituted vesicle membranes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976 Aug 9;71(3):877–884. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90913-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H., Nakae T. The outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. Adv Microb Physiol. 1979;20:163–250. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H. Outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium. Transmembrane diffusion of some hydrophobic substances. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976 Apr 16;433(1):118–132. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(76)90182-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn M. J., Wu H. C. Proteins of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1980;34:369–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.34.100180.002101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZYBALSKI W., BRYSON V. Genetic studies on microbial cross resistance to toxic agents. I. Cross resistance of Escherichia coli to fifteen antibiotics. J Bacteriol. 1952 Oct;64(4):489–499. doi: 10.1128/jb.64.4.489-499.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scudamore R. A., Beveridge T. J., Goldner M. Outer-membrane penetration barriers as components of intrinsic resistance to beta-lactam and other antibiotics in Escherichia coli K-12. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979 Feb;15(2):182–189. doi: 10.1128/aac.15.2.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shales S. W., Chopra I., Ball P. R. Evidence for more than one mechanism of plasmid-determined tetracycline resistance in Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1980 Nov;121(1):221–229. doi: 10.1099/00221287-121-1-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tritton T. R. Ribosome-tetracycline interactions. Biochemistry. 1977 Sep 6;16(18):4133–4138. doi: 10.1021/bi00637a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler H. H., Wilson T. H. The role of energy coupling in the transport of beta-galactosides by Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1966 May 25;241(10):2200–2211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]