Abstract

Objective:

To compare success rate, length of hospital stay, clinical results, and costs of sequential treatment (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy) versus the laparoendoscopic Rendezvous in patients with cholecysto-choledocholithiasis.

Background:

The ideal management of common bile duct (CBD) stones in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) remains controversial.

Methods:

A total of 91 elective patients with cholelithiasis and CBD stones diagnosed at magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) were included in a prospective, randomized trial. The patients were randomized in 2 groups. Group I patients (45 cases) underwent a preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) followed by LC in the same hospital admission. Group II patients (46 cases) underwent LC associated with intraoperative ERCP and ES according to the rendezvous technique.

Results:

The rate of CBD clearance was 80% for Group I and 95.6% for Group II (P = 0.06). The morbidity rate was 8.8% in Group I and 6.5% in Group II (P = not significant). No deaths occurred in either group. Hospital stay was shorter in Group II than in Group I: 4.3 days versus 8.0 days (P < 0.0001). There was a significant reduction in mean total cost for group II patients versus group I patients: €2829 versus €3834 (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

When compared with preoperative ERCP with ES followed by LC, the laparoendoscopic rendezvous technique allows a higher rate of CBD stones clearance, a shorter hospital stay, and a reduction in costs.

To compare success rate, length of hospital stay, clinical results, and costs of sequential treatment (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy) versus the laparoendoscopic rendezvous in patients with cholecysto-choledocholithiasis. When compared with preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with endoscopic sphincterotomy followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the laparoendoscopic rendezvous technique allows a higher rate of common bile duct stone clearance, a shorter hospital stay, and a reduction in costs.

The ideal management of common bile duct (CBD) stones in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) remains controversial. Options range from endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in all or selected patients, through to clearance of the CBD by laparoscopic or laparotomic approach.

LC has tended to encourage surgeons to clear the CBD of stones preoperatively by ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES).1–4 Recently, it has been proposed to perform CBD stones clearance by ERCP and ES during LC to improve patient compliance and perhaps to improve clinical results.5–8

ERCP is a very accurate method of diagnosing CBD stones. However, for diagnostic screening, it appears not to be a viable option because the procedure is associated with a significant risk of complications, including pancreatitis, sepsis, and bleeding. The introduction of magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) into clinical practice has significantly improved the clinical management of patients with suspected CBD stones.9,10 MRC is a noninvasive technique providing both high-quality cross-sectional images of the bile duct structures and projection (coronal) images of the biliary tree. Therefore, MRC has been recently proposed as a screening technique in the preoperative evaluation of patients with suspected CBD stones.11

The aim of this prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) was to compare the length of hospitalization, costs, complication rates, and clinical results of classic sequential treatment (preoperative ERCP + ES followed by LC) versus the so-called laparoendoscopic rendezvous technique5 (preoperative ERCP and ES during LC) in patients suffering from gallbladder and CBD stones diagnosed by MRC. Success/failure rate was the primary endpoint of the study.

METHODS

Patient Selection

All patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis (or acute cholecystitis) and suspected CBD stones admitted to II Division of General Surgery of the University of Turin during the study period were evaluated prospectively for study eligibility. Informed consent was obtained from patients before study participation. The study was approved by our Institution Ethical Committee.

Patients at risk for common duct stones were determined by:

Serum elevation of at least one of the following enzymes: aspartate amino-transferase, alanine aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin.

Abdominal ultrasonography showing possible CBD stones or a dilated CBD (diameter, >8–10 mm).

Patients with acute cholangitis or necrotizing pancreatitis were excluded. Cholangitis was defined as temperature >38.5°C, right upper quadrant pain and tenderness, and hyperbilirubinemia. The diagnosis of gallstone pancreatitis was based on the following criteria: upper abdominal pain and tenderness; serum amylase elevation greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal (>200 U/L); and absence of alcohol abuse, hypercalcemia, hypertriglyceridemia, or medications known to cause pancreatitis. Necrotizing pancreatitis was identified by computed tomography of the abdomen using bolus injection of intravenous contrast.

Further exclusion criteria were: age <18 years, ASA IV and V, suspected CBD malignancy, previous cholecystectomy, contraindications and/or absence of compliance to the diagnostic and/or therapeutic procedures (MRC and ERCP), and finally contraindications to laparoscopic surgery as glaucoma, pulmonary emphysema, and left heart failure. Moreover, patients treated by total or partial gastric resection were excluded.

All patients with the above-mentioned inclusion criteria underwent MRC 1 to 36 hours after admission. Only patients with MRC evidence of CBD stones were eligible for randomization.

Randomization

After obtaining consent, eligible patients were randomized in 1 of 2 groups using sealed opaque envelopes containing computer-generated random numbers. Group I patients underwent preoperative ERCP with ES and after a short period of clinical monitoring (24–72 hours) were submitted to LC. Group II patients underwent LC associated to peroperative ERCP according to the technique of the endo-laparoscopic “rendezvous” described by Cavina et al.5

The protocol for anesthesia was uniform in all patients. Analgesia was carried out with ketorolac or tramadol during the first 24 hours postoperatively and thereafter at the request of the patients. Surgical and endoscopic techniques were standardized before starting the protocol; a single experienced biliary endoscopist (A.G.) performed all ERCPs in both groups of patients, while 2 experienced laparoscopic and hepatobiliary surgeons (M.M., C.M.) performed LCs.

The following data were recorded: operative time including anesthesia, conversion rate, intraoperative and postoperative morbidity, postoperative pancreatic enzymes, 60-day mortality, and length of hospital stay. Failure of ERCP (inability to visualize or to cannulate the CBD) and failure of ES and stone extraction (inability to obtain complete CBD stones clearance at completion cholangiogram) were also noted. Complications were defined as any intraoperative or postoperative (30 days) event that altered the clinical course such as complications of ERCP (including pancreatitis, perforation, and bleeding) and complications of LC (bile duct lesions, bleeding, abdominal collections, pneumoniae, organ failure, etc). Long-term complications, additional procedures, and readmissions were also evaluated.

Cost Analysis

Cost analysis was performed by comparing group I and II with regard to hospital stay, therapeutic ERCP with ES and LC.

Cost evaluation included the use of endoscopic room or operative room (eg, nurse, technical staff, surgical and endoscopic devices, and maintenance), the cost of surgical and endoscopic tools (eg, disposable instruments, trocars, wires, papillotome), and the costs of hospitalization.

At our hospital, the total cost of the operating room is €450 per hour, the total cost of the endoscopic room is 380€, and the normal cost for each day of hospitalization (including the day of admission and the day of discharge) is €300.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint was treatment failure rate defined as failure of ERCP (inability to visualize or to cannulate the CBD), failure of ES and stones extraction (inability to obtain complete CBD stones clearance at completion cholangiogram), and failure to perform LC (conversion to open surgery). Considering a 15% mean failure rate for the sequential treatment (20), appropriate sample size was calculated based on assumption of a difference of 10% in failure rate between the 2 groups to improve the success rate from 85% to 95%. This difference was considered clinically significant, and a sample size of 80 patients (40 in each group) was needed to prove this difference (α set at 0.05; β set at 0.2; power = 80%). Categorical variables were compared by χ2 test, with Yates correction and the Fisher exact test (two-tailed) when necessary. Continuous variables were compared by the Student t test or the Mann-Whitney U test, depending on distribution. All P values were two-sided. A P value of <0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference. Data were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis. All calculations were done with SPSS (version 10.0) SPSS Inc. (Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

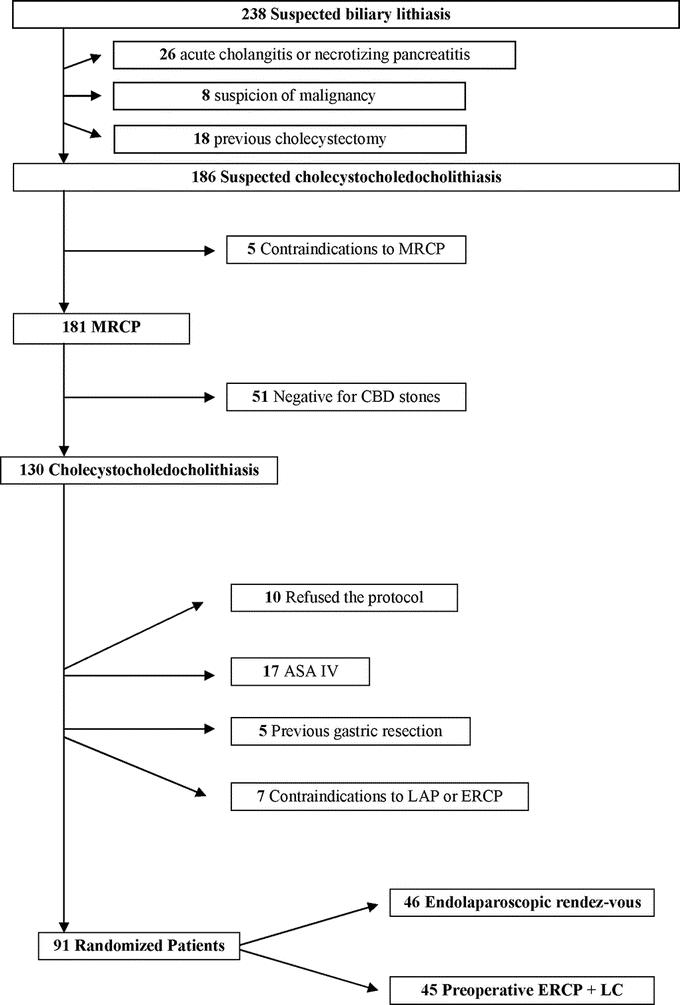

A total of 186 patients with suspected cholecysto-choledocholithiasis (CCL) were admitted to II Division of General Surgery of the University of Turin from May 2001 through August 2005. All patients, except 5 who presented a contraindication to MRC, were submitted to MRC 1 to 36 hours after admission. In 130 cases (72%), MRC diagnosed the presence of CBD stones. After excluding noneligible cases, 91 patients (70%) were included in the trial (Fig. 1) and were randomized to either group I (n = 45) (preoperative ERCP followed by LC) or group II (n = 46) (LC associated to intraoperative ERCP and ES).

FIGURE 1. Study design according to the consort statement.

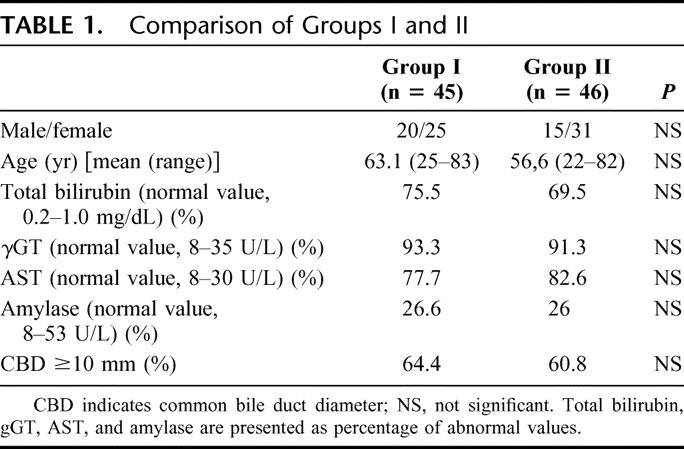

Concerning preoperative parameters (age, sex ratio, ASA status, mean liver enzyme value, etc.), the 2 groups were similar (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Comparison of Groups I and II

Group I Management Outcomes

All patients underwent therapeutic ERCP with ES and stone retrieval. Mean duration of the endoscopic procedure was 45 minutes (range, 25–60 minutes). In 8 patients (17.7%), a mechanic lithotripsy was necessary. In 6 patients (13.3%), a second ERCP was necessary to complete the clearance of the CBD.

In 9 patients (20%), there was a failure of complete duct clearance with preoperative ERCP and ES: in 7 patients (77.7%) because of inability to cannulate the papilla (in 2 patients for the presence of duodenal diverticula) and in 2 cases (22.2%) because of patient's intolerance to the procedure. These patients were submitted in 8 cases to LC and laparoendoscopic rendezvous with a complete clearance of the CBD, and in 1 case to laparotomic cholecystectomy and clearance of the CBD.

There were 3 complications (6.6%) of preoperative ERCP and ES: 2 bleedings and 1 acute prepyloric ulcer all treated medically.

All 45 (100%) group I patients underwent successful LC performed a mean of 4.3 days (range, 1–18 days) after ERCP. In 7 cases, surgery had to be consistently delayed: in a patient with an acute prepyloric ulcer, LC was delayed until clinical ulcer resolution (18 days); and in 6 patients, LC was delayed because of the need of a second ERCP to complete CBD clearance. Mean duration of the laparoscopic procedure was 80 minutes (range, 55–180 minutes).

There were no deaths. There was one postoperative complication (2.2%): an early laparocele on abdominal trocar site treated surgically. Therefore, overall morbidity in this group was 8.8%, including ERCP morbidity (6.6%) and LC morbidity (2.2%).

The mean hospital stay was 8 days (range, 2–34 days).

There were no readmissions nor long-term complications (mean follow-up, 19 months; range, 6–50 months).

Group II Management Outcomes

All patients underwent LC and intraoperative ERCP and ES. In 1 patient (2.1%), a mechanic lithotripsy was necessary. Mean operation time was 127 minutes (range, 90–180 minutes).

In this group, failure rate was 4.4% (2 cases): in 1 patient, a conversion to open surgery was necessary because of unclear anatomy in the Calot triangle; and in 1 patients, large CBD stones were removed by open laparotomy after failed intraoperative endoscopic attempt.

There were no deaths. There were 3 postoperative complications (6.5%): 1 pulmonary acute edema with paroxystic atrial fibrillation and hemobilia, 1 mild pancreatitis, and 1 acute respiratory failure with admission to intensive care unit. All complications resolved with medical therapy.

The mean hospital stay was 4.3 days (range, 2–20 days).

There were no readmissions or long-term complications (mean follow-up, 20 months; range, 6–50 months).

Group Comparisons

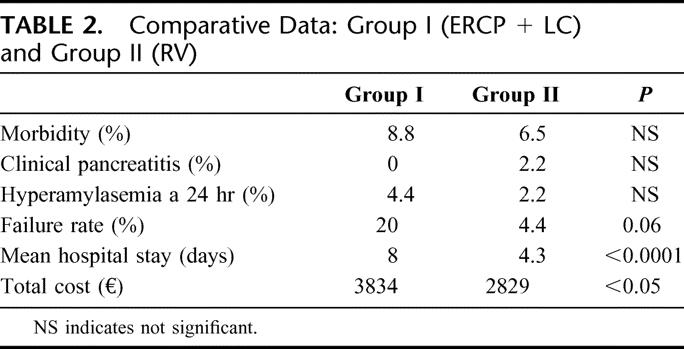

There was a consistent decrease in treatment failures from group I patients (20%) to group II patients (4.4%) (P = 0.06). Mean hospital stay was significantly shorter in group II compared with group I: 4.3 ± 3.1 days (range, 2–20 days; median, 4.3 days) versus 8.0 ± 5.5 days (range, 2–34 days; median, 8 days) (P < 0.001).

There were no statistically significant differences with regard to other clinical parameters such as postoperative morbidity, clinical pancreatitis, or hyperamylasemia (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Comparative Data: Group I (ERCP + LC) and Group II (RV)

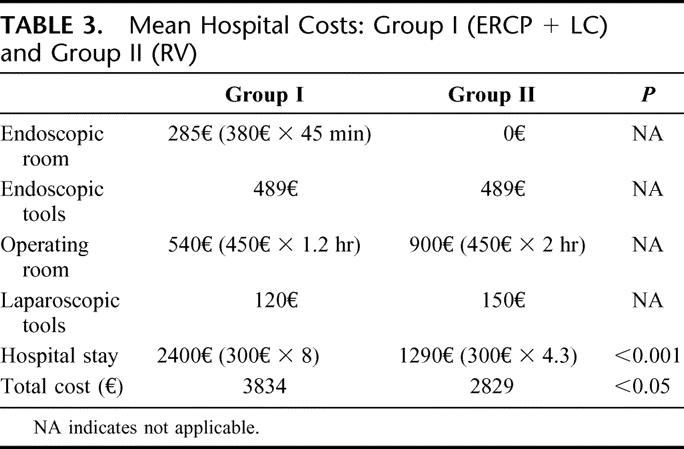

Cost Analysis

The mean costs for the 2 different procedures are summarized in Table 3. There was a significant reduction in mean total costs for group II patients (2.829€) versus group I patients (3.834€) (P < 0.05).

TABLE 3. Mean Hospital Costs: Group I (ERCP + LC) and Group II (RV)

DISCUSSION

LC has become the reference treatment of gallbladder lithiasis, but there is at present no consensus on the ideal management of CCL. In recent years, a few randomized trials have compared different therapeutic strategies: sequential ERCP and LC versus single-stage laparoscopy,4 postoperative ERCP versus laparoscopic choledochotomy,12 preoperative versus postoperative ERCP.13 However, ERCP remains the prevailing method of treating CBD stones,14 but its ideal timing in respect to LC is not defined. Preoperative ERCP followed by LC seems to be the most frequently applied strategy but necessitates 2 successive interventions; LC followed by ERCP presents the risk of a third therapeutic procedure if endoscopy fails to clear the CBD. Theoretically, performing LC and ERCP at the same time should allow to optimize the therapeutic strategy,5–8,15 increasing comfort of the patients who undergo a single minimal-invasive operation under general anesthesia.16

The present study demonstrates that one stage LC and ERCP is superior to sequential ERCP and LC in the management of CCL in terms of success rate, length of hospital stay, and costs. In recent years, different reports have presented encouraging results of one-stage LC and ERCP,5–8 but organization and technical problems have discouraged the diffusion of this combined approach.16 The organization problems depend on the availability of an endoscopist and the necessary material in the operating theater. Improving preoperative diagnosis of CBD stones by MRC9,10 and discussing each case of suspected CCL among a multidisciplinary team, including surgeons, endoscopists, and gastroenterologists,15 could facilitate the diffusion of the rendezvous technique. The presence of experienced biliary endoscopists among our surgical staff did facilitate the performance of laparoendoscopic rendezvous in the present series, reducing organization conflicts between surgeons and gastroenterologists.

The technical problems of the rendezvous technique are related to both the supine position that could make retrograde cannulation of the papilla more difficult as well as to the gas that is needed for endoscopy, which could interfere with LC because of the distension of bowel loops.16

In our study, MRC was used routinely to confirm a suspected diagnosis of CBD stones. Routine use of MRC has 2 main advantages: it avoids the diagnostic use of ERCP and allows to organize in due time the presence of an endoscopist in the operating theater during LC. In the group of patients treated by preoperative ERCP in the present study, LC was performed after a mean of 4.3 days. Although in the study protocol we established to perform LC 24 to 72 hours after ERCP, due to organizational problems (ie, operative room availability, weekends, etc.), or clinical problems (ie, ERCP's complications or the need to perform a second ERCP to complete CBD clearance), the interval between the 2 procedures was in some cases quite consistent. Thus, combining the 2 procedures during the same operation allows to significantly reduce hospital stay (4.3 vs. 8 days) and consequently to significantly reduce the total cost of managing CCL patients (2.829 vs. 3.834€).

Technical solutions have been proposed to solve the difficulties of intraoperative ERCP.5,17,18 Before starting the endoscopic phase, the laparoscopic surgeon should dissect completely both the Calot triangle and the attachment between gallbladder and liver to minimize the dissection needed after ERCP, when the bowel loops will be distended by endoscopic insufflation. Furthermore, an atraumatic laparoscopic bowel clamp should be positioned on the first jejunal loop to reduce bowel distension. To facilitate the identification and cannulation of the papilla, a guidewire is inserted through the cystic duct by the laparoscopic surgeon. The guide is caught with an endoscopic polypectomy loop, extracted from the operative channel and cannulize with a sphincterotome. This is then pulled through the papilla in the CBD, thus completing the so-called “rendezvous technique.”5

In the present study, the laparoendoscopic rendezvous technique presented a reduced failure rate compared with the sequential ERCP and LC: 5% versus 20%. This significant difference has in our opinion 2 main explanations:

In difficult cases (ie, presence of a diverticulum, low patients compliance, etc.), the endoscopist, knowing that there will be a second chance to cannulate the CBD during LC, was very careful at preoperative ERCP and avoided technically risky maneuvers.

During the laparoendoscopic rendezvous, the use of a guidewire reaching the duodenum through the cystic duct facilitates the cannulation of the papilla in difficult cases; this hypothesis is confirmed by the fact that, in 8 cases of 9, after a failure at preoperative ERCP, the laparoendoscopic rendezvous technique was successful in cannulating the papilla and removing CBD stones.

The 95.6% success rate in group II patients treated by laparoendoscopic rendezvous compares favorably with other published rendezvous series reporting a success rate ranging from 90% to 100%6–8,15,19; on the contrary, the 80% success rate in group I patients is unusually low compared with the best published series of preoperative ERCP and ES reporting a success rate ranging from 82% to 96%.20 We think that this difference is a consequence of the above mentioned careful endoscopic attitude; nevertheless, this attitude was rewarded by the absence of severe complications (and specifically pancreatitis) in this group of patients.

Both procedures were safe: there was no mortality and overall morbidity was similar in the 2 groups: 8.8% in the preoperative ERCP patients versus 6.5% in the rendezvous patients (not significant). There was only one major complication among the 2 groups (a severe acute respiratory failure in the laparoendoscopic rendezvous group) and only one reoperation for a ventral hernia at a trocar site in the sequential group.

The major complication of ERCP with ES is acute pancreatitis, although it is generally of a mild grade. This is mostly related to inadvertent cannulation of the pancreatic duct, and only rarely associated with cannulation of the papilla. During the rendezvous technique, the use of a guidewire, allowing an anterograde cannulation of the papilla, avoids the risk of inadvertent cannulation of the pancreatic duct and for some authors21 reduces the rate of pancreatic complications. These data were not confirmed by the present RCT: no differences between the 2 groups in postoperative hyperamylasemia were detected (Table 2), and the only case of pancreatitis occurred in the group of patients submitted to laparoendoscopic rendezvous.

CONCLUSION

Laparoendoscopic rendezvous in the management of CCL is associated with a higher success rate, a shorter hospital stay, and less cost compared with sequential ERCP and LC. These results should lead to an increased use of the laparoendoscopic rendezvous technique, justifying technical and organizational efforts to associate whenever possible laparoscopic surgeons and endoscopists during the same surgical procedure to improve clinical results and reduce patient's discomfort.

Discussions

Dr. James Garden: Thank you very much. As Chairman of the Programme Committee, I guess I should thank myself for volunteering to critique this paper¡ I am grateful for the opportunity to comment on an excellent presentation and you, and your colleagues, are to be congratulated on undertaking a further randomized control trial on what is a common management challenge.

This study has sought to define the optimal management of common bile duct stones, and this has clearly challenged your own group since my understanding is that it has taken you some time to recruit patients for this study because you've been quite selective in the patients that you have included here. Clearly, the question is whether the policy of combining laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative ERCP is better than preoperative ERCP and sphincterotomy.

The technique that you've described is a sequential technique. I guess therein lies the first issue with this study. The sequential technique tends to be the standard approach that is undertaken, I think, in most centers. You yourself have alluded to the success rate of this approach as being about 80% to 96% in the literature, but I am interested to know what it was that actually prompted you to try this new approach. Was this specifically motivated by poor results in your own center for a sequential approach in which ERCP was being undertaken away from or after the cholecystectomy?

The second point regards the study construct, and this is related to this first issue. You have indicated to us the way in which you have undertaken your power calculation, looking actually for a quite ambitious 90% success rate to be converted into a 100% success rate. However, when you look at your data, your success rate with the sequential technique of ERCP is only 80%, which is at the lower end of the spectrum. So has the difference that you've obtained here really arisen because you have demonstrated a poor success rate with sequential ERCP? All patients that have been identified for inclusion into this study have been included on the basis of an MRCP. That's actually an additional investigation. I think that perhaps again, in many centers, for the patient who is considered to be at risk of having common bile duct stones, the performance of an intraoperative cholangiogram would be the way in which the presence of ductal stones would be demonstrated. That's a comment.

The other question, though, is related to the definition of common bile duct stones. You've suggested to us that massive lithiasis is a contraindication for this approach. Can you actually put a number to that? Is it number of stones? Is it size of stones? And, of course, I think you'll also be aware of a very elegant publication from Professor O'Sullivan's group, which has suggested that, at cholecystectomy, many patients are shown to have stones in their common bile duct which are small and which will pass spontaneously without the need for any intervention. So have some patients, in fact, had a rendezvous procedure unnecessarily?

And, finally, the issue of cost. I thought in Italy that the quality and the cost of life was actually quite expensive, but the costs that you have given for the admission of patients to hospital does seem relatively low. Clearly, the ERCP service has been very much under your direction, but I know in my institution, that if I ask for the interventional endoscopists to come to the operating theater to undertake a rendezvous procedure, they are going to say that that this is going to cost the hospital money. They are going to have to cancel an ERCP list that they are doing elsewhere in the hospital. So really are these cost differences to which you are alluding real savings?

I enjoyed the paper very much and thank you for the opportunity to comment on it.

Dr. Mario Morino: Thank you, James, for a very complete analysis of this presentation of the article. Some of the points that you raise should be discussed altogether. The crucial point you made, is the motivation. At least, in our country, in reality, there is a great change of attitude due essentially to the very limited but very severe complications seen with ERCP. ERCP, at least in my hospital, has disappeared completely as a diagnostic procedure. The endoscopists in my unit are getting more and more prudent and cautious when they do an ERCP, sphincterotomy, and so on. It is difficult to accept a potential risk of mortality from a diagnostic procedure, and a very cautious attitude has resulted from a few cases that led to medicolegal problems after ERCP. Patients have died after this procedure, and so the endoscopist is less and less motivated to push in the difficult cases, and this may explain the 80% success. This is associated with the fact that the endoscopists know that they have a second chance to do an easier ERCP during an operation with a patient who is sleeping, with a catheter that comes out from the papilla. They have only to grasp this catheter and so they will not cannulate the pancreas avoiding any false passage. Since we started the rendezvous technique, the attitude of our endoscopists has completely changed. This is the reason, the motivation as you call it, for our study, because we wanted to put on paper this reality. That is the sort of feeling that we have, and this comes also to the problem of the magnetic resonance. At present, for us, this is the standard procedure. It depends very much on the hospital, I know, and I think that everybody here is a surgeon and knows it. In our hospital, if you ask for a CT scan, it needs 2 days. If you ask for an MRI for biliary problems, you will have it 2 hours later. So this comes from the organization, but many studies that have been presented come from this. In our health system, ERCP is going to be used less and less as a diagnostic tool.

Concerning the definition of massive lithiasis, it is true that this is a general one, but it is difficult to go into further details. All the cases were discussed in our staff meeting. I am a disciple of Professor Bismuth so we are used to this staff meeting and the endoscopists are there. In some cases, they judge that this is not a case feasible for endoscopy. Usually, it is not so much the number of stones but the size and the aspect. Sometimes on MRI, the aspect is very square and it feels like something that is very difficult to manage by endoscopy. However, I agree that it is not objective data, but it accounts only for, I think, 3 cases, so it does not change our accrual very much.

Finally, the cost issue. Certainly, you have to take a fellow who should be in one place, and place him somewhere else, but this is connected to the organization of the unit. Three endoscopists are part of my staff: 2 of them stay in the endoscopic ambulatory and 1 comes to the theater. The rendezvous cases are always organized the day before; thus, there are no particular increases in costs. Certainly, you can calculate costs in a more sophisticated way and probably costs evaluation will change slightly. But more or less, the change in costs was not related to the occupation of theater or to the use of doctors but to the hospital stay. The 4 days of difference in hospital did account for the 1000 euros of difference.

Mr. Chris Russell: Professor Garden has asked most of the questions, but I just wonder if I could make a comment. I enjoyed immensely this paper. I think what you've shown in your reply is that different circumstances occur in different places. For instance, our physicians do our endoscopies and they would never dream of coming to theater because they dislike theater, whereas you have obviously well-trained theater-amenable endoscopists.

Nevertheless, the real disadvantage of doing it in theater is that you cannot make full use of the x-ray table and move the patient and tilt the table, or achieve the best quality pictures. This is why our endoscopists say they would never do an ERCP in theater. Their failure rate they would only regard as the end failure rate; if the stone is not easy to remove surgically, I will leave it for the endoscopist. Failure is rare except in the case of very hard and very large stones, which are easy to remove surgically. The endoscopist will put in a stent, they may use lithotripsy of one sort or another, and in time often with several procedures, they will get it out.

And the third point I would make is that with expert endoscopists, the incidence of pancreatitis with the modern endoscopes is disappearing; we have had minimal problems with pancreatitis over the last 10 years. So I think this is one of those papers that is dependent on the circumstances in which you practice.

Dr. Mario Morino: I think all of life depends on where you are and what you are doing, so this is a very general comment¡

For the third point, I did not say that it is better for pancreatitis so I am in line with you. I only said that some authors propose this and that we did not find it in our results. It is not better from pancreatitis, I agree completely.

Concerning the endoscopists, it is the same all over Italy. This procedure is expanding in Italy. In the first congresses, everybody was saying, “I won't come, it's much more difficult, not essentially for their X-rays but because the patient is supine, we are used to the patient lying on their left side etc.” Our endoscopists, the most experienced in our region, now find that ERCP performed during a laparoendoscopic rendezvous is much, much easier and really better. It is completely different since you have only to follow a guide. So, they do not find this problem any more. I must say that, at least in our ERCP room, the x-ray table is not so different from the one we have in the operating room. It is a very good and new one, so it is no different from that point.

Concerning the success rate of preoperative ERCP in removing CBD stones, I agree that in very experienced centers failures are limited to 5% to 10% of cases. Nevertheless, in some cases, it will be necessary to repeat ERCP, sometimes up to three or four times, to obtain a complete clearance; sometimes nasoduodenal-biliary tubes are left in place for 2 or 3 days, sometimes the procedures will last up to 40 or 50 minutes, etc. In our experience, there is a quite limited compliance for ERCP with sphincterotomy and complex stones extraction. What the patient is saying to me is usually “the laparoscopic cholecystectomy was really no problem, but the ERCP was terrible¡ Don't ask me to do it again¡” This is one of the reasons behind the success, at least in our experience, of the rendezvous technique.

Dr. Laureano Fernández-Cruz: A quick comment. I think we have a paradigm in the field of biliary surgery. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy revolutionized the practice of abdominal surgery. We surgeons know that patients with choledocholithiasis should be operated on in one stage. Also, evidence-based papers have demonstrated that one-stage laparoscopy is much better than previous ERCP or rendezvous management on these particular patients.

My question to you as a laparoscopic surgeon is: what is the rationale not to remove the stones as a one-stage laparoscopy and to continue discussing the benefit of ERCP previous to laparoscopic cholecystectomy or the rendezvous approach? I believe that laparoscopic biliary surgeons should have a central role in the management of patients with choledocholithiasis. That is why I think we should interpret this paper with caution. I think that, if we believe that the one-stage laparoscopy is something that should be done, maybe we should discuss the benefit for the patients of one-stage laparoscopy and maybe start to look very critically at the practice of ERCP before surgery or intraoperatively.

Dr. Mario Morino: Thank you for this comment. Well, this is a different subject. There could be a better treatment, but I can still decide to compare two different treatments. So we should not go into the discussion of a third treatment that may be better. My study was on another point, comparing two ways of doing ERCP. My only comment is that it is true, that for some years, some evidence-based studies showed that it is better to operate on these patients by one-stage laparoscopy. But, in the real world, very few centers are doing one-stage laparoscopy. There are many reasons; it is difficult, it is complicated. When you start the procedure, you do not know how much time the procedure will last. I was involved in the EAES trial comparing one-stage with ERCP. Therefore, we have a good experience of laparoscopic management of CBD stones, and sometimes we continue to do it. But there are drawbacks also in this technique, and the real fact is that, at least once again in my experience, this procedure is not encouraging adept surgeons at doing it.

Footnotes

Reprints: Mario Morino, MD, C.so A.M. Dogliotti, 14, 10126 Torino, Italy. E-mail: mario.morino@unito.it.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liu TH, Consorti ET, Kawashima A, et al. Patients evaluation and management with selective use of magnetic resonance cholangiography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 2001;234:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaira D, Ainley C, Williams S, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy in 1000 consecutive patients. Lancet. 1989;2:431–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berci G, Morgersten L. Laparoscopic management of common bile duct stones: a multi-institutional SAGES study. Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:1168–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuschieri A, Lezoche E, Morino M, et al. E.A.E.S. prospective randomized trial comparing two stages vs single stage management of patients with gallstones disease and ductal calculi. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:952–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavina E, Franceschi M, Sidoti F, et al. Laparo-endoscopic ‘Rendezvous’: a new technique in the choledocholithiasis treatment. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1430–1435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tricarico A, Cione G, Sozio M, et al. Endolaparoscopic rendezvous treatment: a satisfying therapeutic choice for cholecystocholedocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:711–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iodice G, Giardiello C, Francica G, et al. Single-step treatment of gallbladder and bile duct stones: a combined endoscopic-laparoscopic technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;3:336–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basso N, Pizzuto G, Surgo D, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy in the treatment of cholecysto-choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;4:532–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirao K, Miyazaki A, Fujimoto T, et al. Evaluation of aberrant bile ducts before laparoscopic cholecystectomy: helical CT cholangiography versus MR cholangiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:713–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanbeckevoort D, Van Hoe L, Ponette E, et al. Imaging of gallbladder and biliary tract before laparoscopic cholecystectomy: comparison of intravenous cholangiography, the combined use of HASTE and single-shot RARE MR imaging. J Belg Radiol. 1997;80:6–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ausch C, Hochwarter G, Taher M, et al. Improving the safety of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: the routine use of preoperative magnetic resonance cholangiography. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:574–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul A, Millat B, Holthausen U, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of common bile duct stones (CBDS): results of a consensus development conference. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:856–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nathanson LK, O'Rourke NA, Martin IJ, et al. Postoperative ERCP versus laparoscopic choledochotomy for clearance of selected bile duct calculi: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2005;242:188–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang L, Lo S, Stabile BE, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in mild to moderate gallstone pancreatitis: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2000;231:82–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NIH. NIH State-of-the Science Statement on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for diagnosis and therapy. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2002;19:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer C, Vo Huu Le J, Rohr S, et al. Management of common bile duct stones in a single operation combining laparoscopic cholecystectomy and perioperative endoscopic sphincterotomy. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:874–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filauro M, Comes P, De Conca V, et al. Combined laparoendoscopic approach for biliary lithiasis treatment. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:922–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deslandres E, Gagner M, Pomp A, et al. Intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakajima H, Okubo H, Masuko Y, et al. Intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Endoscopy. 1996;28:264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enochsson L, Lindberg B, Swahn F, et al. Intraoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to remove common bile duct stones during routine laparoscopic cholecystectomy does not prolong hospitalization: a 2-year experience. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saccomani G, Durante V, Magnolia MR, et al. Combined endoscopic treatment for cholelithiasis associated with choledocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:910–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]