Short abstract

Although the critical factors necessary for IBD pathogenesis remain mysterious, interest in the potential role of defective epithelial barrier function continues to grow. New insight into the mechanisms responsible for barrier dysfunction in IBD may lead to understanding its contribution to disease development and progression.

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, collectively known as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), are major causes of lifetime morbidity. Although these diseases are often differentiated clinically on the basis of disease distribution and morphology, they share many characteristics. Each disease clearly involves an abnormal mucosal inflammatory response, and data from various sources suggest that luminal stimuli and epithelial cell dysfunction can also contribute to disease pathogenesis or progression. Defective epithelial barrier function, which can be measured as increased intestinal permeability, has been implicated in IBD1 and can predict relapse during clinical remission.2,3 Increased permeability is also present in a subset of unaffected first‐degree relatives of patients with Crohn's disease.4,5 As a result of these observations, the mechanisms of barrier function and permeability defects are thought to have a great potential in defining IBD pathogenesis and guiding the development of novel treatments.

The mucosal barrier is established by the single layer of epithelial cells that line the intestine, with erosion and ulcerations being obvious sources of focal barrier defects. The tight junction seals the space between adjacent epithelial cells and, in intact gastrointestinal epithelia, tight junction permeability is the rate‐limiting step that defines the overall epithelial permeability. Thus, tight junction defects may be an important source of the overall intestinal barrier defects—that is, permeability increases—seen in patients with IBD. In this issue of Gut, Zeissig et al6 (see page 61) provide strong evidence that the tight junction barrier function is altered in IBD, and also suggest some specific mechanisms that may underlie these changes.

Tight junctions are composed of multiple proteins that are involved in establishing the epithelial barrier, and they selectively determine which molecules are able to traverse the paracellular space. The claudin family of proteins has a critical role in selective ion permeability; in familial hypomagnesaemia, severe renal Mg2+ and Ca2+ wasting occurs as a result of deficient tubular resorption. This cation transport fails because tight junctions between cells lining the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle are impermeable to these ions as a consequence of claudin‐16 mutations.7 The lack of claudin‐16 correlates with an absence of paracellular channels necessary for Mg2+ and Ca2+ to cross the tight junction. Similarly, claudin‐2 expression in cultured epithelia increases the paracellular permeability of monovalent cations such as Na+.8,9,10 Freeze‐fracture immunoelectron microscopy shows that claudins are often concentrated within tight junction strands, 11 and, remarkably, claudin protein expression induces an assembly of strand‐like structures in fibroblasts that do not normally have tight junctions.12 Higher‐resolution structural analysis of claudin assembly is not available, but the observation that individual claudin isoforms permit a paracellular flux of specific ions suggests that claudin proteins may form ion‐selective pores.

On the basis of our understanding of claudin proteins and the knowledge that ion‐selective and size‐selective tight junction permeability varies throughout the gastrointestinal tract, it is not surprising that the pattern of claudin isoform expression also varies throughout the gastrointestinal tract.13 This site‐specific variation is also regulated temporally during postnatal life.14 Two recent studies have suggested that claudin‐2 expression is increased in the intestinal epithelia in patients with IBD.15,16 Fluorescence microscopy showed that this was particularly true in crypt regions, where claudin‐2 is not normally expressed. Increased claudin‐2 expression could be recapitulated in vitro by treating cultured epithelial monolayers with recombinant interleukin (IL)13, a cytokine in some patients with IBD. Thus, IL13‐dependent increases in claudin‐2 expression may be, at least partially, responsible for the permeability increases seen in patients with IBD.

Zeissig et al6 describe a more comprehensive approach to the problem of barrier loss in IBD. They began by asking whether barrier defects noted in patients with IBD might be due to epithelial damage. Increased epithelial apoptosis was present in patients with active IBD and contributed to focal barrier defects. However, conductance scanning showed a spatially uniform increase in transepithelial conductivity that could not be due to such focal lesions. This suggests that more global mechanisms of increased permeability are involved. Zeissig et al therefore systematically assessed ultrastructural morphology, permeability and tight junction protein expression in intestinal tissues from patients with IBD. Freeze‐fracture electron microscopy showed reduced numbers of tight junction strands but increased numbers of strand breaks in the tissue from patients with active IBD. These were not limited to areas with gross epithelial damage such as ulceration, crypt abscesses or apoptosis. Thus, morphological breakage and loss of tight junction strands were associated with the barrier defects seen in active IBD.6

To gain insight into claudin expression in intestinal tissues from patients with IBD with breakage and loss of tight junction strands, Zeissig et al6 assessed the expression of 12 claudin isoforms. Expression of claudins 3, 5 and 8 was decreased, and immunofluorescence microscopy showed that the proteins were redistributed away from tight junctions in active IBD. Claudin‐2 expression was increased, particularly in the crypt epithelium, in patients with active disease. By contrast, expression of claudin protiens was normal in patients with inactive IBD. The altered pattern of claudin isoform expression seen in intestinal tissues from patients with IBD correlated with the presence of active disease, and may be partly responsible for the observed morphological and functional disruption of tight junctions. However, surprisingly, none of these changes were detected in patients with inactive IBD. This suggests that the altered claudin expression patterns observed are more likely to be a consequence rather than a cause of active disease.

As described earlier, in vitro studies have been used to show that IL13 increases claudin‐2 expression.15,16 Prasad et al15 examined the effect of TNF and interferon γ (IFNγ), two cytokines critical to IBD pathogenesis. Similar to IL13, IFNγ and TNF increased paracellular permeability.15 However, in contrast with IL13, IFNγ and TNF reduced claudin‐2 expression,15 suggesting that the mechanisms by which IFNγ and TNF increase paracellular permeability differ from those used by IL13.15 Zeissig et al did not examine the in vitro effects of IFNγ and TNF on paracellular permeability, but they found that claudin‐2 expression was subtly decreased by IFNγ and modestly increased by TNF.6 It is impossible to ascertain the reason for these discordant results, as there are many experimental differences between the studies: (1) IFNγ and TNF were added simultaneously by Prasad et al15 but separately by Zeissig et al6; (2) a 100‐fold greater TNF dose was used by Zeissig et al6; and (3) different intestinal epithelial cell lines were used in each study. Regardless of these differences, TNF clearly causes intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by mechanisms distinct from altered claudin isoform expression.17

Contemporaneous with the studies discussed above, several groups have investigated the cytoskeletal mechanisms of TNF‐induced paracellular permeability increases.18,19,20 These permeability increases are independent of apoptosis, both in vitro18,20,21,22 and in vivo.23,24 These mechanisms were initially studied using cultured intestinal epithelial monolayers.18 TNF treatment induced marked increases in myosin II regulatory light chain (MLC) phosphorylation that correlated with barrier dysfunction.18 The functional linkage between these events was demonstrated by the observation that inhibition of MLC kinase (MLCK) corrected both MLC phosphorylation and paracellular permeability.18 The mechanistic and pathophysiological relevance of this observation has recently been shown in vivo using a TNF‐dependent model of acute diarrhoea induced in mice after T cell activation.23 The diarrhoea seen in this in vivo model developed within 2–3 h of T cell activation, and was associated with intestinal barrier dysfunction and redistribution of the tight junction protein occludin, but not of the claudins. Increases in intestinal epithelial MLC phosphorylation paralleled the severity of diarrhoea.23 MLCK inhibition, either pharmacologically or by genetic knockout, prevented both intestinal epithelial MLC phosphorylation and barrier dysfunction. More remarkably, MLCK inhibition also restored net water absorption, and therefore corrected the TNF‐dependent diarrhoea.23 These data show that acute cytokine‐dependent diarrhoea can be triggered by cytoskeletally‐mediated barrier regulation. These changes can also occur in the absence of claudin protein redistribution. Thus, both in vitro and in vivo data suggest that TNF regulates barrier function by mechanisms that are separate from claudin isoform modulation.

More detailed in vitro analyses have shown that TNF increases MLC phosphorylation by both transcriptional and enzymatic MLCK activation.19,20,25 Notably, increases in MLCK transcription and expression occurred within hours of TNF addition, and were not associated with altered expression of tight junction proteins, suggesting that the cytoskeletal pathway of TNF‐dependent barrier regulation may occur more rapidly than changes in claudin isoform expression. In addition to these observations in model epithelia, a recent study on resection and biopsy specimens from the intestinal tissue of patients with IBD showed that MLCK expression and enzymatic activity were increased in the intestinal epithelium.26 Similar to the observations of altered expression of the claudin proteins reported by Zeissig et al, the extent to which MLCK expression and activity were increased correlated positively with disease activity.26 In contrast with claudin expression, MLCK expression was modestly increased in patients with histologically inactive IBD.26 These data suggest that increased intestinal epithelial MLCK expression may be a stable characteristic of patients with IBD.

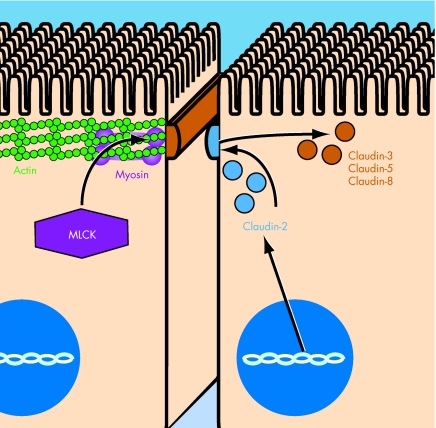

When considered as a whole, the data on MLCK and claudins suggest the possibility of a biphasic induction of barrier defects in patients with IBD. For example, a patient with inactive IBD and mild chronically increased MLCK expression may be more likely to develop an exaggerated permeability defect in response to an environmental or inflammatory stimulus (fig 1). This induces a local inflammatory response, perhaps including TNF release, thereby perpetuating barrier dysfunction. Over time, this enables the development of a more prolonged inflammatory response with the release of mediators, including IL13, that regulate claudin isoform expression. This results in further distortion of barrier function, including disruption of normal ion selectivity that enhances diarrhoea and malabsorption. Thus, it is possible to envisage a model in which acute and rapidly reversible barrier defects induced by MLCK activation give way to more stable chronic barrier defects resulting from altered claudin protein expression. Both of these mechanisms disrupt barrier function and potentiate disease activity.

Figure 1 Model of barrier dysfunction pathogenesis in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Acute and rapidly reversible barrier defects occur via myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) activation and actomyosin contraction (exemplified by the cell on the left). One major mediator of such acute changes is tumour necrosis factor, which affects transcriptional and enzymatic activation of MLCK. Acute changes may then evolve into more stable chronic barrier defects (exemplified by the cell on the right). Interleukin 13 is one among the cytokines that may have a role in changing the expression and distribution of claudin protein isoforms. Individual claudin isoforms can be either increased or decreased. For example, in active IBD, claudin‐2 (blue) expression is increased in the crypt epithelium. By contrast, expression of claudins 3, 5 and 8 (brown) is decreased in active disease. This changes the overall claudin isoform composition at the tight junction, and possibly results in a major change in barrier function.

This model is useful because it allows for the development of testable hypotheses to improve our understanding of the pathogenesis of barrier dysfunction in IBD. However, many critical questions remain unanswered. (1) The primary defect causing increased MLCK expression or permeability defects in IBD is unknown. (2) It remains unclear whether barrier dysfunction is an important risk factor for the development of IBD. Clearly, barrier dysfunction alone cannot be sufficient to cause the disease, as increased permeability is seen in some unaffected relatives of patients with IBD.5 (3) Relatively little information is available to explain how cytokines may work together to modify claudin expression patterns, either in vitro or in vivo. (4) Although the changes in claudin isoform expression and distribution in disease are striking and in vitro data show that altered expression of specific claudin isoforms modifies paracellular ion conductance, basic understanding of tight junction structure and of the biophysical consequences of claudin isoform substitution or redistribution is lacking. These are important gaps in our knowledge base that will require further study.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01DK61931 and RO1DK68271) and the Crohn's Colitis Foundation of America.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Hollander D. Crohn's disease—a permeability disorder of the tight junction? Gut 1988291621–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnott I D R, Kingstone K, Ghosh S. Abnormal intestinal permeability predicts relapse in inactive Crohn disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2000351163–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wyatt J, Vogelsang H, Hubl W.et al Intestinal permeability and the prediction of relapse in Crohn's disease. Lancet 19933411437–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz K D, Hollander D, Vadheim C M.et al Intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn's disease and their healthy relatives. Gastroenterology 198997927–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peeters M, Geypens B, Claus D.et al Clustering of increased small intestinal permeability in families with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 1997113802–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeissig S, Bürgel N, Günzel D.et al Changes in expression and distribution of claudins 2, 5 and 8 lead to discontinuous tight junctions and barrier dysfunction in active Crohn's disease. Gut 20075661–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon D B, Lu Y, Choate K A.et al Paracellin‐1, a renal tight junction protein required for paracellular Mg2+ resorption. Science 1999285103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amasheh S, Meiri N, Gitter A H.et al Claudin‐2 expression induces cation‐selective channels in tight junctions of epithelial cells. J Cell Sci 20021154969–4976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furuse M, Furuse K, Sasaki H.et al Conversion of zonulae occludentes from tight to leaky strand type by introducing claudin‐2 into Madin‐Darby canine kidney I cells. J Cell Biol 2001153263–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Itallie C M, Fanning A S, Anderson J M. Reversal of charge selectivity in cation or anion‐selective epithelial lines by expression of different claudins. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2003285F1078–F1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furuse M, Fujita K, Hiiragi T.et al Claudin‐1 and ‐2: novel integral membrane proteins localizing at tight junctions with no sequence similarity to occludin. J Cell Biol 19981411539–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasaki H, Matsui C, Furuse K.et al Dynamic behavior of paired claudin strands within apposing plasma membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 20031003971–3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahner C, Mitic L L, Anderson J M. Heterogeneity in expression and subcellular localization of claudins 2, 3, 4, and 5 in the rat liver, pancreas, and gut. Gastroenterology 2001120411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes J L, Van Itallie C M, Rasmussen J E.et al Claudin profiling in the mouse during postnatal intestinal development and along the gastrointestinal tract reveals complex expression patterns. Gene Expr Patterns 20066581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prasad S, Mingrino R, Kaukinen K.et al Inflammatory processes have differential effects on claudins 2, 3 and 4 in colonic epithelial cells. Lab Invest 2005851139–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heller F, Florian P, Bojarski C.et al Interleukin‐13 is the key effector th2 cytokine in ulcerative colitis that affects epithelial tight junctions, apoptosis, and cell restitution. Gastroenterology 2005129550–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clayburgh D R, Shen L, Turner J R. A porous defense: the leaky epithelial barrier in intestinal disease. Lab Invest 200484282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zolotarevsky Y, Hecht G, Koutsouris A.et al A membrane‐permeant peptide that inhibits MLC kinase restores barrier function in in vitro models of intestinal disease. Gastroenterology 2002123163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma T Y, Boivin M A, Ye D.et al Mechanism of TNF—a modulation of Caco‐2 intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier: role of myosin light‐chain kinase protein expression. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2005288G422–G430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang F, Graham W V, Wang Y.et al Interferon‐gamma and tumor necrosis factor‐alpha synergize to induce intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by up‐regulating myosin light chain kinase expression. Am J Pathol 2005166409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang F, Schwarz B T, Graham W V.et al IFN‐g‐induced TNFR2 upregulation is required for TNF‐dependent intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction. Gastroenterology 20061311153–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruewer M, Luegering A, Kucharzik T.et al Proinflammatory cytokines disrupt epithelial barrier function by apoptosis‐independent mechanisms. J Immunol 20031716164–6172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clayburgh D R, Musch M W, Leitges M.et al Coordinated epithelial NHE3 inhibition and barrier dysfunction are required for in vivo TNF‐mediated diarrhea. J Clin Invest 20061162682–2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clayburgh D R, Barrett T A, Tang Y.et al Epithelial myosin light chain kinase‐dependent barrier dysfunction mediates T cell activation‐induced diarrhea in vivo. J Clin Invest 20051152702–2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graham W V, Wang F, Clayburgh D R.et al TNF induced long myosin light chain kinase transcription is regulated by differentiation dependent signaling events: characterization of the human long myosin light chain kinase promoter. J Biol Chem 2006269462–9470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blair S A, Kane S V, Clayburgh D R.et al Epithelial myosin light chain kinase expression and activity are upregulated in inflammatory bowel disease. Lab Invest 200686191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.