Abstract

Background

Intestinal nutrients induce gut reflexes and modulate perception.

Aim

To elucidate the relative potency and putative relationship of motor and sensory effects induced by different nutrients.

Methods

By paired tests carried out in sequence on healthy patients, the effect of isocaloric duodenal infusions of carbohydrates and lipids was determined on gastric compliance and on perception of gastric distension. Gastric distension at stepwise tension increments was applied using a tensostat, and perception at each tension level was measured on a 0–6 scale. In separate groups (n = 8 each), three nutrient loads were tested: (A) low (0.2 kcal/min), (B) medium (0.5 kcal/min) and (C) high (1 kcal/min).

Results

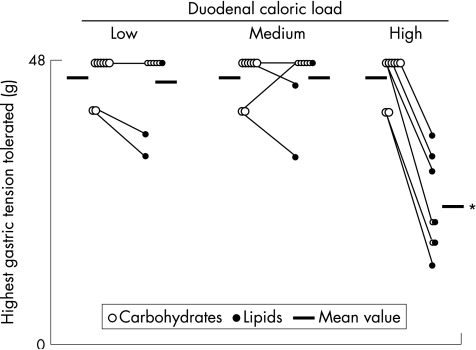

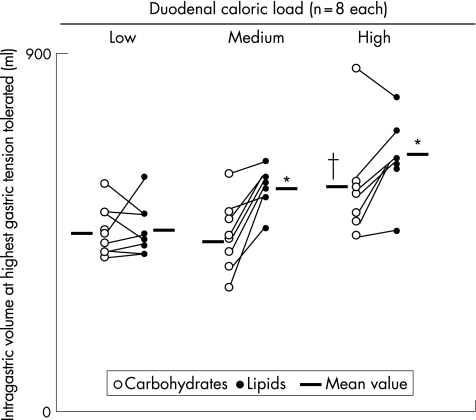

Values are mean (standard error). (A) Low caloric loads: both gastric perception and compliance were similar with lipids (45 (2) g, 451 (28) ml tolerated) and carbohydrates (46 (1) g, 449 (22) ml tolerated). (B) Medium caloric loads: although perception remained unchanged (46 (1) g and 46 (2) g tolerated, respectively), lipids, but not carbohydrates, partially relaxed the stomach (559 (18) v 442 (31) ml intragastric volume, respectively; p<0.05). (C) High caloric loads: lipids markedly reduced gastric tolerance and increased compliance (22 (3) g, 635 (34) ml tolerated), whereas carbohydrates did not affect perception and induced only a partial gastric relaxation (46 (1) g, 565 (46) ml tolerated; p<0.05 v lipids for both).

Conclusion

The effects of intestinal nutrients on gastric tone are more potent than those on gastric sensation, and both depend on the caloric load and the type of nutrient.

Intestinal nutrients modulate gastric tone via relaxatory reflexes, and thereby control gastric accommodation and emptying.1,2 However, intestinal nutrients also exert a modulatory role on visceral sensation, and increase gastric perception by sensitising afferent pathways. 3,4,5,6 These actions depend on the type of nutrients,4,5 but the putative interdependency of sensory and reflex effects has not yet been systematically investigated. Our aim was to dissect both effects and correlate the response kinetics of gastric sensitisation (increased gastric perception) and reflexes (gastric relaxation) induced by different types of intestinal nutrients.

The issue considered is highly relevant, because gastric sensitisation and altered reflexes are likely to be involved in the genesis of symptoms in functional dyspepsia.7,8,9,10,11 However, from a technical standpoint, dissecting the purely sensory effects from the mechanical effects of intraluminal nutrients on gastric function is technically challenging, because gastric relaxation has confounding effects on perception. Moreover, the effect of gastric relaxation on sensations induced by distension depends on the testing paradigm. Perception of gastric distension depends on gastric wall tension, which by Laplace's law is related to both intragastric volume and pressure.8,12 Fixed‐volume gastric inflation produces lower intragastric pressure and lower perception when the stomach is relaxed.12,13 By contrast, fixed intragastric pressure applied using a barostat results is larger intragastric volume and higher perception when the stomach is relaxed.13

These limitations can be overcome by applying fixed levels of gastric wall tension using a computerised tensostat.12 With a tension‐driven paradigm, perception is related to wall tension regardless of gastric tone, intragastric pressure and volume: the same tension levels result in larger intragastric volumes and in smaller intragastric pressures when the stomach is relaxed, but perception remains unchanged.12 Hence, to achieve our aim, in a group of healthy people, we compared the effects of different isocaloric doses of carbohydrates and lipids on gastric perception and compliance in response to standardised levels of gastric distension applied using a tensostat.

Participants and methods

Participants

Twenty four healthy people without gastrointestinal symptoms (12 women and 12 men; median age 24 (range 21–28) years) participated in the study after giving written informed consent. Participants were recruited by public advertising among university students (local Caucasian population) with body mass index within the normal range (defined as between 18.5 and 25 kg/m2). The protocol for the study had been previously approved by the institutional review board of the University Hospital Vall d'Hebron, Barcelona, Spain.

Duodenal nutrient infusion

Using an intraluminal polyvinyl tube (3.2 mm outer diameter,1.6 mm inner diameter), nutrient solutions were continuously infused at a rate of 2 ml/min using an infusion pump (Compact Enteral Feeding Pump; Sandoz Nutrition, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). Isocaloric amounts of carbohydrates (Maxijul; Scientific Hospital Supplies, Barcelona, Spain) or lipids (Intralipid 20%; Pharmacia & Upjohn, St Cugat del Vallés, Spain) were infused. Different caloric concentrations with the same osmolarity (300 mOsm/l) were adjusted by diluting the nutrients with saline solution.

Gastric distension and compliance

A constant tension level on the gastric wall was applied using a computerised tensostat (Tensostat/Barostat; Sicie, Barcelona, Spain), connected via a double‐lumen polyvinyl tube (12‐F catheter, Argyle; Sherwood Medical, Tullamore, Ireland) to an intragastric bag (capacity 900 ml, maximum perimeter 18 cm). The system calculates online gastric wall tension by applying Laplace's law (based on transmural pressure and intragastric volume, assuming that air conforms to a spherical shape), and drives the pump to maintain the desired tension level. Transmural pressure was calculated by subtracting the intra‐abdominal pressure from the intraluminal pressure during gastric distension, which was determined at the beginning of each study (details in Procedure). A detailed description of the tensostat has been published previously.12,14

Perception measurements

Perception was quantified using a graded questionnaire to measure the intensity and type of sensations, and an anatomical questionnaire to measure the location and extension of sensations.8,11,12 The graded questionnaire included four graphic rating scales graded from 0 (no perception) to 6 (maximum tolerated), specifically for scoring the following abdominal sensations: pressure, fullness, nausea and any other type of sensation (to be specified). Participants were asked to score any perceived sensation (one or more perceived sensations simultaneously) on the scales. The anatomical questionnaire incorporated a diagram of the abdomen divided into the following regions: medial and lateral regions above and below the umbilicus. Participants were instructed to indicate using the diagram in which abdominal region (one or more) the sensations were perceived. Participants were also instructed to report the extension and depth of the referred sensations. For this purpose, they were provided with six numbered circles that covered 0.5%, 2.5%, 5%, 20%, 50% and 100% of the abdominal surface in the diagram depicted in the anatomical questionnaire, and were asked to select the circle that best encompassed the extension of the referral area. Participants were also provided with a wedge diagram that depicted four concentric strata from the abdominal surface to the innermost abdominal core (depth levels 0%, 33%, 66% and 100% from the abdominal surface), and were asked to select the level corresponding to the depth of the referred sensation.

Procedure

Participants were orally intubated after 6 h of fasting. The intestinal infusion tube was positioned under fluoroscopic control in the duodenum 10 cm distal to the pylorus, and the bag of the barostat was introduced into the stomach and connected to the system. A 10‐min resting period was given before starting the recordings. The studies were conducted in a quiet, isolated room with participants sitting on an ergonomic chair with their trunk erect.

First, 10 ml air was injected into the gastric bag, and intraluminal pressure was averaged for 2 min as an index of intra‐abdominal pressure.12 Fifteen minutes after starting the duodenal nutrient infusion—that is, when 30 ml had been injected—ramp gastric distensions were performed in 4‐g steps every 3 min up to a 48‐g upper limit or less if participants reported discomfort before, and then the nutrient infusion was discontinued. At the end of each distending step, participants were asked to report the sensations perceived during the preceding minute. After a 30‐min interval, the procedure was repeated again using the other type of isocaloric nutrient solution. The 30‐min interval was chosen based on previous data, indicating that the effects on gastric tone of duodenal nutrients loads in the range tested faded in <20 min after interrupting the infusion.15 The duration of the study did not exceed 3 h.

Experimental design

Nutrient infusions of carbohydrates and lipids were tested at three caloric loads. Each caloric load was tested in a different group of participants (n = 8 each). The sample size was calculated on the basis of previous data,15 expecting a different effect on gastric tone at the highest caloric load of lipids versus carbohydrates in 80% of the participants, with a power of 80% and a risk of α = 5%. In each participant, isocaloric infusions of carbohydrates and lipids were sequentially tested in the same experiment in random order. A low caloric load (0.2 kcal/min) was tested in five women and three men (median age 24 (range 21–27) years; lipids were tested first in three participants), a medium caloric load (0.5 kcal/min) in four women and four men (median age 24 (range 20–30) years; lipids were tested first in two participants) and a high load (1 kcal/min) in three women and five men (median age 23 (range 21–26) years; lipids were tested first in three participants).

Outcome measures

At each level of gastric wall tension tested, intragastric volume and pressure were measured by averaging the computerised recordings during the last minute of the distension step, and perception was measured by the score in the questionnaire (when more than one sensation was scored, only the highest score, instead of the cumulative or mean score, was used). The effect of nutrients was evaluated by comparing the mean responses to the common distension levels tested during isocaloric infusions of different nutrients in the same participants (lipids v carbohydrates), or different caloric loads of the same type of nutrients in separate groups of participants (low v medium v high caloric loads).

Statistical analysis

Mean (standard error (SE)) values of the parameters measured were calculated in each group of participants. Data were compared using Wilcoxon's signed rank test for paired intragroup comparisons and the Mann–Whitney U test for unpaired intergroup comparisons. The frequency of different sensations was compared using contingency tables by the χ2 test.

Results

Effects of low caloric load (0.2 kcal/min)

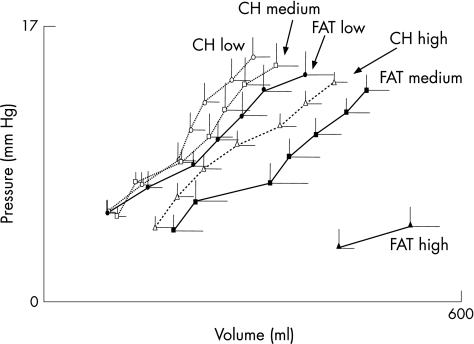

During both carbohydrate and lipid infusions, gradual increments in gastric wall tension resulted in progressive increments in intragastric volume and perception scores. The highest gastric wall tension level tested was similar during both carbohydrate and lipid infusions (fig 1). At these tension levels, the intragastric volume (fig 2) and the intensity of perception (mean (SE) score 4.0 (0.6) with carbohydrates and 4.1 (0.5) with lipids) were similar with both types of nutrients. Furthermore, comparing the full range of common tension levels tested during both carbohydrate and lipid infusions (8–32 g) in each participant, we detected no differences in intragastric volumes (211 (21) and 243 (29) ml, respectively), compliance (fig 3) or perception scores (1.2 (0.4) and 2.1 (0.3), respectively).

Figure 1 Effect of duodenal nutrients on gastric sensitivity. Values are highest gastric tension levels tolerated by each individual (and mean in each group). Similar levels of gastric wall tension were tolerated during duodenal infusion of either carbohydrates or lipids both at low (0.2 kcal/min) and medium (0.5 kcal/min) caloric loads. At the high caloric load (1 kcal/min), lipids increased gastric perception and thereby reduced the tolerance to distension. *p<0.05 versus carbohydrate and versus lower loads.

Figure 2 Effect of duodenal nutrients on gastric tone. Values are intragastric volumes at the highest distension level tolerated by each individual (and mean in each group). Both the high carbohydrate and the medium lipid loads induced a partial gastric relaxation (greater intragastric volumes at similar tension levels), whereas the high lipid load had a markedly stronger relaxatory effect, with even larger intragastric volumes despite the fact that the tension levels tolerated were significantly lower. *p<0.05 versus carbohydrate and versus lower loads; †p<0.05 versus lower loads.

Figure 3 Gastric compliance. Values are mean (SE) intragastric volumes and pressures at the gastric distension levels tolerated by all participants during duodenal infusion of carbohydrates (CH) or lipids (FAT): between 8 and 32 g during all nutrient infusions, except the high caloric lipid load (FAT high) that was tolerated only up to 12 g.

Effects of medium caloric loads (0.5 kcal/min)

The highest gastric wall tension level tested was similar during both carbohydrate and lipid infusions (fig 1). Furthermore, at these tension levels, perception was similar with carbohydrates (mean (SE) score 3.6 (0.7)) and with lipids (3.6 (0.6)). However, intragastric volumes were significantly larger during lipid infusion than during carbohydrate infusion (p<0.05; fig 2). The same results were obtained by comparing the common tension levels tested in each participant during both carbohydrate and lipid infusions (8–32 g), with no differences in perception scores (1.4 (0.4) and 1.6 (0.4), respectively), but significantly higher intragastric volumes for lipids (347 (41) v 229 (26) ml for carbohydrates; p<0.05) and also compliance (fig 3).

We detected no differences in the highest tolerated tension by comparing low and medium loads of both carbohydrates and lipids, indicating a lack of effect on gastric sensation (fig 1). Intragastric volumes during the medium carbohydrate load were similar to those during the low load, indicating a lack of effect on gastric compliance (fig 2). By contrast, the medium lipid load induced a relaxatory effect, reflected by the larger intragastric volumes observed during medium than during the low lipid dose (p<0.01; fig 2).

Effects of high caloric loads (1 kcal/min)

At the high caloric load, the different effects of carbohydrates and lipids on gastric compliance and perception (sensation with highest score) became apparent. During lipid infusion, the highest gastric wall tension levels tested were much lower (fig 1) but induced more intense perception than during carbohydrate infusion (6.0 (SD 0.0) score with lipid v 4.3 (SD 0.5) score with high carbohydrate load; p<0.05). Furthermore, intragastric volume and compliance at these tension levels were also significantly larger during lipid than during carbohydrate infusion (figs 2, 3).

Comparing the mean responses at 8‐g and 12‐g wall tension levels (distensions common to all participants), intragastric volumes and perception scores were significantly higher during the high lipid infusion (430 (34) ml, score 2.4 (0.4)) than during medium (209 (44) ml, score 0.1 (0.1)) or low (109 (17) ml, score 0.4 (0.1)) lipid loads, indicating a stronger effect of the high lipid infusion (p<0.05 for both). The same type of analysis comparing the effect of different loads of carbohydrates at identical tension levels (8–32 g) showed that high carbohydrate loads produced larger intragastric volumes (292 (24) ml; p <0.05) but similar perception scores (1.6 (0.4); p = NS) than medium and low carbohydrate loads (see data above). During high‐load carbohydrate infusion, the intragastric volume was not influenced by the order of the tests: mean volume between 8‐g and 32‐g tension was 276 (29) ml in participants who received the lipid infusion first and 301 (34) ml in those in whom the carbohydrate solution was tested first, and we observed no differences at any of the individual distensions. These results suggest a partial but an important effect of the high carbohydrate load on gastric compliance without affecting perception. The effect of the high carbohydrate load (partial effect on gastric compliance, but no effect on perception) was similar to that of the medium lipid load.

Sensations induced by gastric distension

No participant reported sensations before starting the nutrient infusions, except one who reported nausea score 1 before starting the high caloric lipid infusion. The type of sensations was similar during low and medium carbohydrate and lipid loads (fig 4). However, nutrient‐specific differences were detected at the high nutrient loads: greater proportions of pressure and fullness were associated with carbohydrates, as opposed to nausea with lipids. Nevertheless, the high lipid load in itself did not seem to induce nausea, because at 8 g gastric wall tension, the nausea score was similar to that during carbohydrate infusion (scores 1.8 (0.5) and 0.8 (0.4), respectively; p = NS). Sensations were referred to the epigastrium, left hypochondrium and hypogastrium (in 50%, 14% and 9% of occasions, respectively), without major differences during carbohydrate and lipid infusions. No dose‐related differences in the extension of the referral area were detected, but the extension was larger during carbohydrate infusion than during lipid infusion (sensations perceived over 40% (7%) v 21% (3%) of the abdomen, respectively; p<0.05). The depth of the sensations was not influenced by the concentration or the type of the nutrient load (sensations were perceived 46% (9%) beneath the abdominal surface with lipids, and 39% (7%) with carbohydrates, respectively; p = NS).

Figure 4 Effect of duodenal nutrient infusion on the sensations induced by gastric distension. Pie charts show the average proportions of all sensations perceived during the entire gastric distension test, and numerical values are the mean perception scores. The quality of the sensations perceived during the low and medium nutrient loads was similar, but at high loads, nutrient‐specific differences (more nausea during lipid infusion) were found (p<0.001 by the χ2 test).

Discussion

Our data indicate that the effects of intestinal nutrients on gastric sensitivity and reflexes are dissociable. The effects of intestinal nutrients on gastric tone are more potent than those on gastric sensation, and both depend on the caloric load and the type of nutrient.

At low caloric loads (0.2 kcal/min), the responses to gastric distension during carbohydrate and lipid infusions were not different, conceivably because this dose was well below the physiological loads and was ineffective. The normal gastric emptying rate of a mixed meal is about 1–2 kcal/min,16 and depending on its composition, each individual nutrient principle, protein, lipid or carbohydrate, accounts for a fraction of the emptying rate. Hence, the medium caloric load of a single nutrient tested (0.5 kcal/min) could be considered within the physiological range. At this medium dose, nutrient‐related differences were apparent. Whereas carbohydrates had no effect (no different from the low dose), lipids induced a partial relaxation of the stomach without affecting perception (perception was no different from the low dose). At the highest dose tested (1 kcal/min), carbohydrates had a partial effect on gastric compliance without affecting perception, whereas the high lipid load still induced a considerably larger gastric relaxation, and at the same time, heightened mechanosensitivity. A partial effect on the gastric tone of a physiological dose of carbohydrates with respect to lipids had been shown previously in a similar paradigm,14 but the relationship of motor and sensory effects is an original contribution of this study.

It has been shown previously that intestinal nutrients exert a nutrient‐specific regulation of the gastric tone.4,5 As the gastric tone determines gastric emptying, these regulatory mechanisms adapt, by a negative feedback control, the nutrient delivery load to the intestinal processing capability. Furthermore, by relaxing the stomach, nutrients increase the tolerance to intragastric filling,4,6,17 and thus contribute to the unperceived gastric accommodation. These effects are nutrient specific and dose related, and depend also on the region of the intestine stimulated.2,4,6,17 Also, species‐specific differences may exist. In dogs, in the proximal intestine, lipids, but not carbohydrates, induced relaxatory reflexes,1 the same as in humans. In the distal intestine, carbohydrates in dogs produced a very potent and prolonged inhibition of gastric tone, but lipids had no effect.1 This second effect of lipids may be at variance with humans, which shows a lipid‐induced “ileal brake” of proximal gut motility and transit,18 that may also involve gastric control.19

Nutrient‐related and region‐related differences in these responses may have functional implications. The complex process of lipid digestion in the proximal small bowel may require a fine‐tuning of the gastric emptying rate to prevent intestinal lipid overload. By contrast, the relatively straightforward process of carbohydrate absorption may require only a distal control to prevent small‐bowel escape and colonic spilling.

The sensitising effect of lipids antagonises and partly compensates the increased volume tolerance that would result from gastric relaxation, and thereby may keep satiation signals at acceptable volume loads. However, at higher lipid loads, sensitisation may be part of a physiological alarm system indicating excessive intestinal load. Increased perception of gastric distension induced by lipids was associated with a change in the symptom pattern. Whereas gastric distension normally induces, by and large, a sensation of pressure or fullness, lipid‐induced sensitisation is associated with a considerably greater feeling of nausea, which may be related to the vomit response to high lipid loads.5,6

Nutrient‐induced reflexes are vagally mediated by a non‐adrenergic, non‐cholinergic mechanism,14 which may involve serotonin receptors and nitric oxide transmission.20 Cholecystokinin receptors may also play a part by sensitising the vagal afferent response,21 but only in the presence of long‐chain fatty acids.17,22 Gastric perception is initiated by the stimulation of tension receptors, and the afferent signal is then driven by sympathetic–splanchnic–spinal afferent pathways.2,12,23 This sensory input is modulated by various mechanisms at different levels of the gut–brain axis.11,23 Lipids have been shown to sensitise mechanoreceptors' response,3,24 which would explain why lipid infusion increases the perception of gastric distension. Lipid doses that extensively increase the perception of gut distension do not modify the perception of transmucosal electrical nerve stimulation (which directly activates sensory afferents bypassing mechanoreceptors3). However, intestinal nutrients activate vagal afferents, and experimental animal data indicate that vagal stimulation reduces afferent input in viscerosensory pathways.25 Conceivably, the net effect of nutrients may depend on the interaction of various mechanisms.

We have carefully considered the potential limitations related to the methods and study design. The study was designed to compare the relative power of isocaloric loads of carbohydrates and lipids, because dose‐related effects were specifically investigated in a previous study, which also served to determine the appropriate wash‐out periods between sequential nutrient loads.15 The partial gastric relaxation observed during the high carbohydrate load could be potentially related to a carry‐over effect of lipids, but the relaxation was similar regardless of the order of nutrient administration. The invasive method used may have biased the perception, and the gastric relaxatory effect of lipids could be related to the perception of nausea. However, analogous gastric tone responses to carbohydrates and lipids were observed in a previous study using the barostat at low intragastric pressure levels, where neither the nutrient loads nor the gastric relaxatory responses were perceived.15 Furthermore, it has also been shown that the barostat in itself does not distort the gastric‐emptying pattern.26 In any case, the low caloric load, without detectable effects in the present studies, could serve as the reference control for higher nutrient loads.

The relevance of our study lies in the novel information it provides on the mechanisms by which intestinal nutrients regulate physiological food processing and eventually signal dysfunction. However, our data also have important pathophysiological implications. It has been shown that enterogastric relaxatory reflexes, including those induced by nutrients, are impaired in patients with functional dyspepsia,7,8 and may affect meal accommodation.9,10 Inadequate gastric relaxation does not affect gastric emptying, because final gastric outflow is regulated by other mechanisms,2,26 but reduces the tolerance to intragastric volume loads.12,13 Patients with dyspepsia also have a gastric hypersensitivity that worsens in the presence of intestinal nutrients.8 The characterisation of nutrient‐induced effects on gastric accommodation, affecting both compliance and perception, may help in explaining the pathophysiology of postprandial symptoms of dyspepsia. Additionally, the demonstration of two independent motor and sensory mechanisms may also give rise to separate and possibly synergic therapeutic options, targeting at restoring reflexes and neutralising sensitisation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Anna Aparici and Maite Casaus for technical support, and Gloria Santaliestra for secretarial assistance.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported in part by the Spanish Ministry of Education (Dirección General de Enseñanza Superior del Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, BFI 2002‐03413), the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (grant C03/02) and the National Institutes of Health, USA (grant DK 57064).

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Azpiroz F, Malagelada J ‐ R. Intestinal control of gastric tone. Am J Physiol 1985249G501–G509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayer E A, Gebhart G F. Basic and clinical aspects of visceral hyperalgesia. Gastroenterology 1994107271–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Accarino A, Azpiroz F, Malagelada J ‐ R. Modification of small bowel mechanosensitivity by intestinal fat. Gut 200148690–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbera R, Feinle C, Read N W. Nutrient‐specific modulation of gastric mechanosensitivity in patients with functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci 1995401636–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feinle C, Grundy D, Read N W. Effects of duodenal nutrients on sensory and motor responses of the human stomach to distension. Am J Physiol 1997273(Pt 1)G721–G726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feinle C, Grundy D, Fried M. Modulation of gastric distension‐induced sensations by small intestinal receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2001280G51–G57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffin B, Azpiroz F, Guarner F.et al Selective gastric hypersensitivity and reflex hyporeactivity in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 19941071345–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caldarella M, Azpiroz F, Malagelada J ‐ R. Antro‐fundic dysfunctions in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 20031241220–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tack J, Caenepeel P, Fischler B.et al Symptoms associated with hypersensitivity to gastric distention in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2001121526–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tack J, Bisschops R, Sarnelli G. Pathophysiology and treatment of functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 20041271239–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azpiroz F. Gastrointestinal perception: pathophysiological implications. Neurogastroenterol Mot 200214229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Distrutti E, Azpiroz F, Soldevilla A.et al Gastric wall tension determines perception of gastric distension. Gastroenterology 19991161035–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Notivol R, Coffin B, Azpiroz F.et al Gastric tone determines the sensitivity of the stomach to distension. Gastroenterology 1995108330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azpiroz F, Salvioli B. Barostat measurements. In: Schuster MM, Crowel MD, Koch KL, eds. Schuster atlas of gastrointestinal motility in health and disease. Hamilton, ON: BC Decker, 2002151–170.

- 15.Carrasco M, Azpiroz F, Malagelada J ‐ R. Modulation of gastric accommodation by duodenal nutrients. World J Gastroenterol 2005114848–4851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marsh M N, Ryley S A. Digestion and absorption of nutrients and vitamins. In: Feldman M, Scharschmidt BF, Sleisenger MH, eds. Sleisenger & Fordtran's gastrointestinal and liver disease: pathophysiology/diagnosis/management. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 19981471–1500.

- 17.Feinle C, Rades T, Otto B.et al Fat digestion modulates gastrointestinal sensations induced by gastric distention and duodenal lipid in humans. Gastroenterology 20011201100–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spiller R C, Trotman I F, Higgins B E.et al The ileal brake—inhibition of jejunal motility after ileal fat perfusion in man. Gut 198425365–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller L J, Malagelada J R, Taylor W F.et al Intestinal control of human postprandial gastric function: the role of components of jejunoileal chyme in regulating gastric secretion and gastric emptying. Gastroenterology 198180763–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coulie B, Tack J, Sifrim D.et al Role of nitric oxide in fasting gastric fundus tone and in 5‐HT1 receptor‐mediated relaxation of gastric fundus. Am J Physiol 1999276(Pt 1)G373–G377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davison J S, Clarke G D. Mechanical properties and sensitivity to CCK of vagal gastric slowly adapting mechanoreceptors. Am J Physiol 1988255(Pt 1)G55–G61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lal S, McLaughlin J, Barlow J.et al Cholecystokinin pathways modulate sensations induced by gastric distension in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2004287G72–G79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sengupta J N, Gebhart G F. Gastrointestinal afferents and sensation. In: Johnson LR, ed. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. New York: Raven, 1994483–519.

- 24.Melone J. Vagal receptors sensitive to lipids in the small intestine of the cat. J Auton Nerv Syst 198617231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ren K, Randich A, Gebhart G F. Effects of electrical stimulation of vagal afferents on spinothalamic tract cells in the rat. Pain 199144311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moragas G, Azpiroz F, Pavía J.et al Relations among intragastric pressure, postcibal perception and gastric emptying. Am J Physiol 1993264G1112–G1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]