Abstract

Background

Disease‐related prion protein (PrPSc) is readily detectable in lymphoreticular tissues in variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD), but not in other forms of human prion disease. This distinctive pathogenesis, with the unknown population prevalence of asymptomatic vCJD infection, has led to significant concerns that secondary transmission of vCJD prions will occur through a wide range of surgical procedures. To date PrPSc:prion infectivity ratios have not been determined in vCJD, and it is unknown whether vCJD prions are similar to experimental rodent prions, where PrPSc concentration typically reflects infectious prion titre.

Aim

To investigate prion infectivity in vCJD tissue containing barely detectable levels of PrPSc.

Methods

Transgenic mice expressing only human PrP (Tg(HuPrP129M+/+Prnpo/o)‐35 and Tg(HuPrP129M+/+Prnpo/o)‐45 mice) were inoculated with brain or rectal tissue from a previously characterised patient with vCJD. These tissues contain the maximum and minimum levels of detectable PrPSc that have been observed in vCJD.

Results

Efficient transmission of prion infection was observed in transgenic mice inoculated with vCJD rectal tissue containing PrPSc at a concentration of 104.7‐fold lower than that in vCJD brain.

Conclusions

These data confirm the potential risks for secondary transmission of vCJD prions via gastrointestinal procedures and support the use of PrPSc as a quantitative marker of prion infectivity in vCJD tissues.

Most people in the UK might have been exposed to bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) prions, the causative agent of the novel human prion disease, variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD).1 The unknown, but potentially high prevalence of clinically silent infection with BSE prions,1,2,3 allied with the distinctive pathogenesis of vCJD,4,5,6,7,8 has led to significant concerns that there may be substantial risks of iatrogenic transmission of vCJD prions via blood products, and contaminated surgical and medical instruments.1,5,8,9,10 Two cases of transfusion‐associated vCJD prion infection have now been reported,11,12 with a third probable case announced by the UK Health Protection Agency in February 2006. Prions resist many conventional sterilisation procedures, and surgical stainless steel‐bound prions transmit disease with remarkable efficiency when implanted into mice.10,13

Although bioassay is generally regarded as the gold standard for prion detection in experimental studies, a substantial transmission barrier limits the sensitivity of such methods to assay vCJD prions in conventional mice.14,15,16 Risk assessment for secondary transmission of vCJD prions has thus relied on high‐sensitivity immunoblot detection of disease‐related prion protein (PrPSc) to inform on the potential levels of prion infectivity in vCJD tissues. These methods, with conventional immunohistochemistry, have shown that the tissue distribution of PrPSc in vCJD differs strikingly from that in classical CJD, with uniform and prominent involvement of lymphoreticular tissues.4,5,6,7,8,17 Depending on the density of lymphoid follicles, PrPSc concentrations in vCJD peripheral tissues can vary enormously, with levels relative to brain as high as 10% in tonsil4,5 or as low as 0.002% in rectum.5

According to the protein‐only hypothesis18 of prion propagation, PrPSc is the principal component of the infectious prion.14,19,20 However, it is well recognised that the ratio of PrPSc to infectivity varies in different prion disease models and that prion diseases may occur without detectable PrPSc.21,22,23 However, as comparative end‐point titration of vCJD prions in humans cannot be carried out, PrPSc:prion infectivity ratios have not been determined in vCJD. In this regard, it is unknown whether vCJD prions are similar to experimental rodent prions, where PrPSc concentration typically reflects infectious prion titre.24

To investigate this, we inoculated transgenic mice expressing only human PrP (Tg(HuPrP129M+/+Prnpo/o)‐35 and Tg (HuPrP129M+/+Prnpo/o)‐45 mice referred to as 129MM Tg35 and Tg45 mice, respectively)15,25 with brain and rectal tissue from a previously characterised patient with vCJD.5 These tissues contain the maximum and minimum levels of detectable PrPSc that we have observed in vCJD, with the concentration of PrPSc in rectum being 104.7‐fold lower than that in brain.5

Methods

This study was carried out after approval from the Institute of Neurology/National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery Local Research Ethics Committee.

All procedures were carried out in a microbiological containment level 3 facility, with strict adherence to safety protocols.

Transmission studies

Care of mice was according to institutional guidelines. Transgenic mice homozygous for a human PrP 129 methionine (M) transgene array and murine PrP null alleles (Prnpo/o), designated Tg (HuPrP129M+/+Prnpo/o)‐35 mice and Tg (HuPrP129M+/+Prnpo/o)‐45 mice (129MM Tg35 and 129MM Tg45 mice), have been described previously.15,25 129MM Tg35 and Tg45 mice have 9 and 17 copies of the transgene, respectively, resulting in respective expression of human PrP at levels two or fourfold higher than human brain.15 vCJD brain (frontal cortex) and vCJD rectum (full thickness tissue) were prepared as 10% w/v homogenates in Dulbecco's sterile phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) lacking Ca2+ and Mg2+ by either serial passage through needles of decreasing diameter (brain) or use of Duall tissue grinders (rectum). After intracerebral inoculation with tissue homogenate (30 μl 1% w/v tissue homogenate in PBS) as described previously,15 mice were examined daily and were killed if they exhibited signs of distress, or once a diagnosis of clinical prion disease was established.26 Brains from inoculated mice were analysed by high‐sensitivity immunoblotting and by neuropathological examination.

Immunohistochemisry

vCJD rectum or transgenic mouse brain was analysed with anti‐PrP monoclonal antibody ICSM 35 (D‐Gen Ltd, London, UK), using a Ventana automated immunohistochemical staining machine (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, Arizona, USA) as described previously.3,8,27 Briefly, tissue was fixed in 10% buffered formal saline followed by incubation in 98% formic acid for 1 h. After further washing for 24 h in 10% buffered formal saline, tissue samples were processed and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections were cut at a nominal thickness of 4 μm, treated with 98% formic acid for 5 min and then boiled in a low ionic strength buffer (2.1 mM TRIS, 1.3 mM EDTA, 1.1 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.8) for 20 min. Abnormal PrP accumulation was examined using anti‐PrP monoclonal ICSM 35, followed by a biotinylated anti‐mouse IgG secondary antibody (iView Biotinylated Ig, Ventana Medical Systems) and an avidin–biotin horseradish peroxidase conjugate (iView SA‐HRP, Ventana Medical Systems) before development with 3′ 3 diaminobenzidine tetrachloride as the chromogen (iView DAB, Ventana Medical Systems). Haematoxylin was used as the counterstain. Haematoxylin and eosin staining of serial sections was performed using conventional methods. Appropriate controls were used throughout.

Immunoblotting

Human or mouse tissues prepared as 10% w/v homogenates in PBS were analysed by proteinase K digestion (50 or 100 μg/ml final protease concentration, 1 h, 37°C) and immunoblotting with anti‐PrP monoclonal antibody 3F428 using high‐sensitivity enhanced chemiluminescence as described previously.5 Sodium phosphotungstic acid precipitation of PrPSc from tissue homogenate29 was carried out as described previously.5 This method facilitates highly efficient recovery and detection of PrPSc from vCJD tissue homogenate when present at levels 104–105‐fold lower than that in vCJD brain.3,5 Densitometry of immunoblots was carried out using ImageMaster 1D software (GE Healthcare UK, Chalfont, St Giles, UK).

Results

Immunoblot detection of PrPSc in vCJD rectal tissue

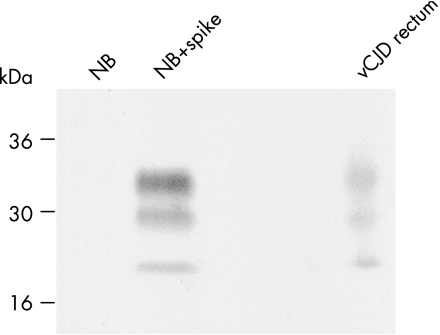

Previously, we reported the distribution of PrPSc in autopsy tissues from four patients with neuropathologically confirmed vCJD.5 In one of these patients we detected PrPSc in rectum at a concentration of 1/50 000 (10−4.7) of that present in brain.5 To generate inocula for transmission studies, we prepared a new series of 10% w/v homogenates from this rectal tissue and analysed 0.5 ml of each homogenate for detectable PrPSc by sodium phosphotungstic acid precipitation, proteinase K digestion and high‐sensitivity immunoblotting.5 Through this analysis, we again identified one 10% rectum homogenate containing PrPSc at a level of about 1/50 000 of that present in the brain (fig 1). Previously we reported that the glycoform ratio of protease‐resistant PrP fragments in vCJD rectum might be distinct from type 4t PrPSc seen in vCJD tonsil.5 However, PrPSc fragments in the newly prepared rectum homogenate showed a clear predominance of diglycosylated PrP, consistent with the glycoform ratios of PrPSc seen in other vCJD lymphoreticular tissues.4,5 We consider that the apparent difference in the glycoform ratio of rectal PrPSc observed between different tissue homogenates simply reflects the difficulty in carrying out such analysis at the limits of detection sensitivity.

Figure 1 Immunoblot detection of disease‐related prion protein (PrPSc) in variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) rectal tissue. Proteinase K digested sodium phosphotungstic acid pellets from 0.5 ml of 10% normal human brain homogenate (NB) or 0.5 ml of 10% normal human brain homogenate spiked with 50 ml of 10% vCJD brain homogenate (NB+spike) are compared with a proteinase K digested sodium phosphotungstic acid pellet from 0.5 ml of 10% rectum of homogenate from the same patient with vCJD. The immunoblot was analysed with anti‐prion protein (PrP) monoclonal antibody 3F4 using high‐sensitivity of chemiluminescence. Densitometry showed that the PrPSc signal from 0.5 ml of 10% rectum homogenate has an intensity equivalent to 20% of that derived from 50 ml of 10% vCJD brain homogenate. The PrPSc concentration in rectum homogenate is thus about 1/50 000 of that present in brain homogenate.

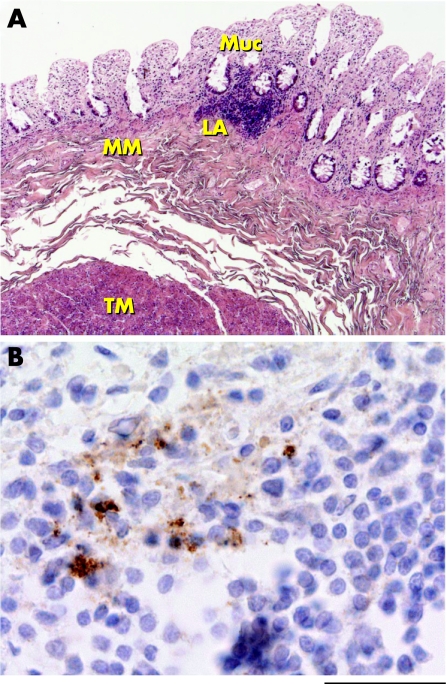

Unfortunately, PrPSc positive vCJD rectum was available only as frozen tissue and consequently this precluded immunohistochemical examination. Recently, however, we have been able to examine both frozen and formalin‐fixed rectal tissue from another patient with vCJD. Analysis of three 10% homogenates prepared from this tissue by high‐sensitivity immunoblotting failed to show detectable PrPSc. However, immunohistochemical examination of rectal tissue at multiple levels showed abnormal PrP immunostaining in one of eight identified submucosal lymphoid aggregates (fig 2). No abnormal PrP immunostaining was found in the mucosa, in muscularis mucosae or in the nerves of the submucosal plexus. Although only a single sample such as this must be treated cautiously, these findings suggest that abnormal PrP immunoreactivity in vCJD rectum is probably associated mainly with lymphoid tissue, as observed in other areas of the intestine in vCJD.2,7,8,27,30 The relative paucity of lymphoid tissue in rectum (in comparison to terminal ileum, where PrPSc is uniformly detected in vCJD8) seems likely to underlie the irregular detection of PrPSc in rectal tissue homogenates by immunoblotting.

Figure 2 Immunohistochemical detection of abnormal prion protein (PrP) deposition in variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) rectum. (A) Haematoxylin and eosin staining of vCJD rectum. Muc, mucosa; LA, submucosal lymphoid aggregate; MM, muscularis mucosae; TM, tunica muscularis. (B) Abnormal PrP immunoreactivity in a submucosal lymphoid aggregate in vCJD rectum (anti‐PrP monoclonal antibody ICSM 35). The immunostaining pattern is similar to that observed previously in vCJD terminal ileum.8 Scale bar: (A) 500 μm; (B) 40 μm.

Prion transmission from vCJD rectal tissue

Previously, we showed that challenge of transgenic mice expressing human PrP 129M (129MM Tg35 and 129MM Tg45 mice) with vCJD brain results in 100% transmission of prion infection, with uniform propagation of type 4 PrPSc accompanied by the key neuropathological hallmark of vCJD—the presence of abundant florid PrP plaques.15 However, most of the mice in these transmissions do not develop clinical prion disease; instead, they remain subclinically affected until they succumb to either intercurrent illness or senescence. This lack of clinical end point precludes conventional estimation of prion titre through serial dilution and incubation period methods,26,31 and the demonstration of vCJD prion transmission in these mice therefore relies on detection of PrPSc in brain.15,25

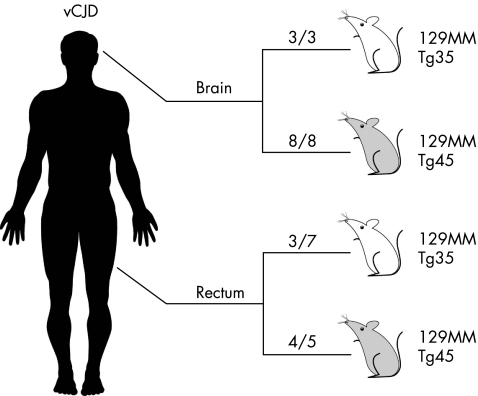

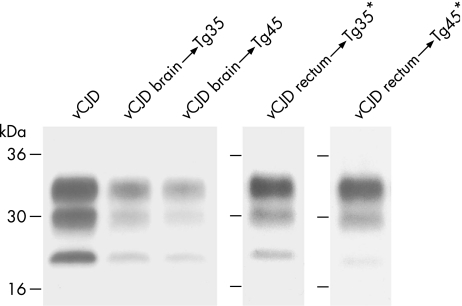

Consistent with other vCJD brain isolates,15 brain inocula from the vCJD patients with PrPSc positive rectum produced a 100% attack rate of subclinical prion infection in both the 129MM Tg35 and Tg45 mice (table 1, fig 3). This was shown by typical neuropathological changes15,25 (data not shown) and by immunoblot detection of PrPSc in the brain of all inoculated mice (table 1, fig 4). In most of these mice (9 of 11) PrPSc was readily detected by direct immunoblotting (table 1) and we were able to establish the propagation of type 4 PrPSc (fig 4).

Table 1 Prion transmission from variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) brain and rectum to transgenic mice.

| 129MM Tg35 mice | 129MM Tg45 mice | |

|---|---|---|

| Inocula* | Attack rate† | Attack rate† |

| I3140 vCJD brain | 3/3‡ | 8/8§ |

| I3247 vCJD rectum | 3/7¶ | 4/5** |

*Mice were inoculated intracerebrally with 30 μl of 1% tissue homogenate. Disease‐related prion protein (PrPSc) concentration in rectum homogenate was 104.7‐fold lower than brain homogenate.

†Attack rate reports the number of mice propagating PrPSc in brain as a proportion of the number of inoculated mice. Brains scored negative for PrPSc after analysis of 20 μl of 10% brain homogenate were re‐analysed by sodium phosphotungstic acid precipitation of PrPSc from 250 μl of 10% brain homogenate. All PrPSc positive mice were asymptomatic for clinical prion disease.

‡Affected mice died at 228, 272 and 418 days after inoculation. PrPSc was reliably detected in two brain homogenates by direct immunoblotting and in one brain homogenate only after sodium phosphotungstic acid precipitation.

§Affected mice died 161–606 days after inoculation. PrPSc was reliably detected in seven brain homogenates by direct immunoblotting and in one brain homogenate only after sodium phosphotungstic acid precipitation.

¶Affected mice died at 563, 575 and 585 days after inoculation. PrPSc was reliably detected in brain homogenates only after sodium phosphotungstic acid precipitation. Non‐affected mice died at 377, 412, 462 and 563 days after inoculation.

**Affected mice died at 362, 404, 424 and 550 days after inoculation. PrPSc was reliably detected in brain homogenates only after sodium phosphotungstic acid precipitation. The single non‐affected mouse died at 455 days after inoculation.

Figure 3 Prion transmission from variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) brain and rectum to transgenic mice. The total number of prion‐affected mice is reported for each inoculated group: 129MM Tg35 mice (white) and 129MM Tg45 mice (grey). Transgenic mice were scored positive for prion infection by immunoblot detection of disease‐related prion protein (PrPSc) in brain.

Figure 4 Disease‐related prion protein (PrPSc) detection in variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) prion transmissions to transgenic mice. Immunoblots of proteinase‐K‐treated brain homogenates from vCJD and transgenic mice were analysed by enhanced chemiluminescence with anti‐prion protein (PrP) monoclonal antibody 3F4. The identity of the brain sample is designated above each lane. * denotes PrPSc recovered by sodium phosphotungstic acid precipitation.

Remarkably, prion infection was also clearly evident in 7 of 12 mice inoculated with vCJD rectal tissue containing a 104.7‐fold lower concentration of PrPSc than brain (table 1, figs 3 and 4). However, in these transmissions, the level of PrPSc propagated in affected mouse brain was much lower than seen after inoculation with vCJD brain, and sodium phosphotungstic acid preconcentration was required for reliable detection of PrPSc (table 1, fig 4). Consistent with these low concentrations of PrPSc, PrP immunohistochemistry was negative in affected mice (data not shown). Importantly, despite the requirement for phosphotungstic acid preconcentration, the level of PrPSc in affected mouse brain was in all cases >103‐fold higher than that present in the vCJD rectum inoculum, which itself would have been undetectable. Moreover, although sodium phosphotungstic acid precipitation precludes accurate PrP fragment size analysis used to distinguish prion strain types,5 the glycoform ratio of PrPSc propagated in the brain of vCJD rectum‐inoculated mice was consistent with type 4 PrPSc (fig 4). Collectively, these data provide convincing evidence for prion transmission from vCJD rectal tissue. The relative difference in the concentration of PrPSc propagated in the brain of transgenic mice inoculated with vCJD rectum or vCJD brain is consistent with a tissue‐specific difference in the prion titre of the inoculum.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown the presence of prion infectivity in vCJD rectal tissue. As already stated, the levels of PrPSc detected in vCJD tissues cannot be directly correlated with units of human prion infectivity. However, if levels of prion infectivity in vCJD brain approach the highest levels seen in experimental rodent models (108 intracerebral infectious U/ml 10% brain homogenate29,31,32), then vCJD rectal tissue with a 104.7‐fold lower PrPSc concentration might contain 103.3 intracerebral infectious U/ml 10% homogenate.5 Bioassay of 30 μl of 1% rectal homogenate would thus correspond to injection of only approximately 6 human intracerebral infectious units. The fact that efficient prion transmission has occurred in transgenic mice after inoculation with vCJD rectal tissue is consistent with PrPSc:prion infectivity ratios in vCJD being closely similar to experimental rodent prion strains. These findings strongly endorse the value of PrPSc analysis in vCJD for defining risk reduction strategies to limit secondary transmission of vCJD prions.

The ready demonstration of prion infectivity in vCJD rectum, despite barely detectable levels of PrPSc, clearly suggests even higher prion titres in other vCJD peripheral tissues in which greater levels of PrPSc have been consistently shown. In this regard, it is of note that vCJD tonsil has been shown to transmit prion infection to wild‐type mice despite the presence of a transmission barrier.16 Our present findings with vCJD rectum, together with the demonstration of much greater levels of PrPSc in vCJD terminal ileum,8 reinforce concerns that iatrogenic transmission of vCJD prions might occur through contaminated intestinal endoscopes, biopsy forceps or surgical instruments.9,33

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank C O'Malley and C Powell for technical assistance with immunohistochemistry and R Young for preparation of the figures. We thank all patients and their families for generously consenting to the use of human tissues in this research, and the UK neuropathologists who have kindly helped in providing these tissues.

Abbreviations

BSE - bovine spongiform encephalopathy

CJD - Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

PBS - phosphate‐buffered saline

PrP - prion protein

PrPSc - disease‐related prion protein

vCJD - variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

Footnotes

Funding: This work was funded by the UK Medical Research Council and was carried out under the approval from the Institute of Neurology/National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery Local Research Ethics Committee.

References

- 1.Collinge J. Variant Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. Lancet 1999354317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilton D A, Ghani A C, Conyers L.et al Prevalence of lymphoreticular prion protein accumulation in UK tissue samples. J Pathol 2004203733–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frosh A, Smith L C, Jackson C J.et al Analysis of 2000 consecutive UK tonsillectomy specimens for disease‐related prion protein. Lancet 20043641260–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill A F, Butterworth R J, Joiner S.et al Investigation of variant Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease and other human prion diseases with tonsil biopsy samples. Lancet 1999353183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wadsworth J D F, Joiner S, Hill A F.et al Tissue distribution of protease resistant prion protein in variant Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease using a highly sensitive immuno‐blotting assay. Lancet 2001358171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilton D A, Sutak J, Smith M E.et al Specificity of lymphoreticular accumulation of prion protein for variant Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. J Clin Pathol 200457300–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Head M W, Ritchie D, Smith N.et al Peripheral tissue involvement in sporadic, iatrogenic, and variant Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease: an immunohistochemical, quantitative, and biochemical study. Am J Pathol 2004164143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joiner S, Linehan J M, Brandner S.et al High levels of disease related prion protein in the ileum in variant Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. Gut 2005541506–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bramble M G, Ironside J W. Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease: implications for gastroenterology. Gut 200250888–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson G S, McKintosh E, Flechsig E.et al An enzyme‐detergent method for effective prion decontamination of surgical steel. J Gen Virol 200586869–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Llewelyn C A, Hewitt P E, Knight R S.et al Possible transmission of variant Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease by blood transfusion. Lancet 2004363417–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peden A H, Head M W, Ritchie D L.et al Preclinical vCJD after blood transfusion in a PRNP codon 129 heterozygous patient. Lancet 2004364527–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flechsig E, Hegyi I, Enari M.et al Transmission of scrapie by steel‐surface‐bound prions. Mol Med 20017679–684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collinge J. Prion diseases of humans and animals: their causes and molecular basis. Annu Rev Neurosci 200124519–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asante E A, Linehan J M, Desbruslais M.et al BSE prions propagate as either variant CJD‐like or sporadic CJD‐like prion strains in transgenic mice expressing human prion protein. EMBO J 2002216358–6366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruce M E, McConnell I, Will R G.et al Detection of variant Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease infectivity in extraneural tissues. Lancet 2001358208–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glatzel M, Abela E, Maissen M.et al Extraneural pathologic prion protein in sporadic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. N Engl J Med 20033491812–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffith J S. Self replication and scrapie. Nature 19672151043–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prusiner S B. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science 1982216136–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prusiner S B. Prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 19989513363–13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collinge J, Palmer M S, Sidle K C L.et al Transmission of fatal familial insomnia to laboratory animals. Lancet 1995346569–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lasmezas C I, Deslys J ‐ P, Robain O.et al Transmission of the BSE agent to mice in the absence of detectable abnormal prion protein. Science 1997275402–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill A F, Desbruslais M, Joiner S.et al The same prion strain causes vCJD and BSE. Nature 1997389448–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prusiner S B. Molecular biology of prion diseases. Science 19912521515–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wadsworth J D F, Asante E A, Desbruslais M.et al Human prion protein with valine 129 prevents expression of variant CJD phenotype. Science 20043061793–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlson G A, Kingsbury D T, Goodman P A.et al Linkage of prion protein and scrapie incubation time genes. Cell 198646503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joiner S, Linehan J, Brandner S.et al Irregular presence of abnormal prion protein in appendix in variant Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 200273597–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kascsak R J, Rubenstein R, Merz P A.et al Mouse polyclonal and monoclonal antibody to scrapie‐associated fibril proteins. J Virol 1987613688–3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Safar J, Wille H, Itri V.et al Eight prion strains have PrPSc molecules with different conformations. Nat Med 199841157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ironside J W, Head M W, Bell J E.et al Laboratory diagnosis of variant Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. Histopathology 2000371–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prusiner S B, Cochran S P, Groth D F.et al Measurement of the scrapie agent using an incubation time interval assay. Ann Neurol 198211353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flechsig E, Shmerling D, Hegyi I.et al Prion protein devoid of the octapeptide repeat region restores susceptibility to scrapie in PrP knockout mice. Neuron 200027399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Axon A T, Beilenhoff U, Bramble M G.et al Variant Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease (vCJD) and gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy 2001331070–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.