We report a case of a patient with an inflammatory syndrome cured after resection of an adenoma. A 33‐year‐old woman was admitted to the department of internal medicine in May 2004 for invalidating pain in the spinal cord in the context of an inflammatory syndrome. The patient had been on oral contraceptives (Adepal) for the past 16 years. The inflammatory syndrome involved fever (37.4–38°C), anaemia, C reactive protein 90 mg/l, fibrinogen 7 g/l, sedimentation rate 106 mm and haptoblobin 2.9 g/l. Investigations for infectious, viral, systemic, hormonal and haematological disorders were all negative.

Liver function tests showed abnormally high levels of alkaline phosphatase (×3N), γ‐glutamyltransferase (×2N), and alanine aminotransferase (×1.5N). Liver ultrasound scan showed two nodules in the right lobe (12 and 4 cm across), which was confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and three additional 1‐cm‐nodules in the same lobe. A right hepatectomy was performed in November 2004. In March 2005, the inflammatory syndrome had normalised: the red blood cell count was 4.4 T/l, haemoglobin 12.7 g/dl, hematocrite 39.2%, mean globular volume 93 μm3, C reactive protein 3 mg/l, sedimentation rate 6 mm, and liver tests had returned to normal values. MRI performed in August 2005 was normal.

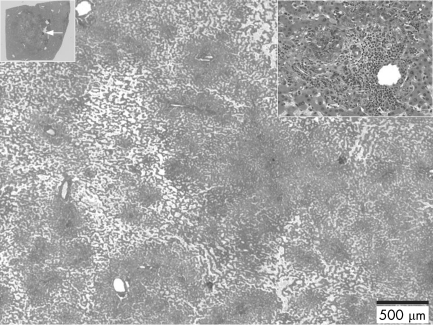

Three major nodules (9×8 cm, 4.5×2.5 cm and 1.5×1.5 cm) and numerous smaller ones (<1 cm across) were identified macroscopically. The main nodules were non‐encapsulated, poorly delimited, with soft, pink, red and yellowish areas. Some of the larger nodules had the typical aspect of inflammatory/telangiectatic adenoma as described previously (fig 1).1 Most of the smaller nodules were steatotic. The non‐tumoral liver was generally normal, except for the presence of some isolated or grouped lobules that were either entirely steatotic or with slightly dilated sinusoids.

Figure 1 Small nodule with telangiectatic features. This nodule is shown at a low power (upper left corner), with the white arrow indicating the border with the non‐tumoral tissue. In the upper right corner is a closer view showing pseudo portal tracts with inflammatory cells and a mild ductular reaction.

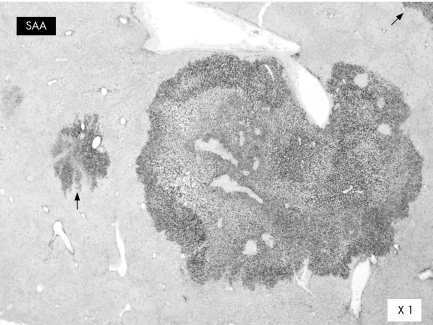

Hepatocyte cytoplasm was strongly immunostained for AA amyloid (serum amyloid A) in all nodules, whether steatotic or telangiectatic; there was a clear demarcation with the adjacent liver (fig 2). We identified a germline HNF1α gene variant A→T at codon 1573 leading to a T525S amino acid substitution in the frozen liver tissue and blood lymphocytes. No additional somatic mutation was found in the tumour, and mRNA of both HNF1α alleles was detected.2 No activating β‐catenin mutation was found in the tumour.

Figure 2 Serum amyloid A immunostaining (telangiectatic nodule) with sharp boundary. Only hepatocytes are labelled. Note the additional positive foci (arrows) in the surrounding liver.

We recently described a new four‐group classification of adenomas on the basis of genotype/phenotype correlation3: adenomas with mutation of the HNF1α gene, adenomas with mutation of the β‐catenin gene and adenomas without either mutation, constituted with and without inflammatory lesions. The group with inflammatory features is comparable to the entity previously called “telangiectatic focal nodular hyperplasia”.1

We have reported a case of a morphologically typical multiple inflammatory adenoma (so called adenomatosis because of the large number of nodules), although different aspects were observed in different areas of the same tumour and in different nodules. There have been several reports of an inflammatory syndrome with systemic or renal amyloidosis in patients with liver adenomas, which was cured by hepatic resection or adenoma regression.4,5,6,7,8,9,10 Fibrillar deposits were described in the liver, in the Disse space or in vessels, or in both. Our case strengthens the idea of the existence of inflammatory adenomas. In contradiction with previous reports,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 we did not detect any extracellular deposit of serum amyloid A in the liver, but there was a strong labelling of tumoral hepatocytes. The reason for this is unclear. Whatever the explanation, the mechanism of the inflammatory process is unknown.

All HNF1α mutations identified from nearly 50% of hepatocellular adenomas were inactivating and biallelic.2 Consequently, the role, if any, of the germline HNF1α variant A→T at codon 1573 leading to a T525S amino acid substitution is unknown. Indeed, this T525S variant has not been described previously in the general population; it may be a rare polymorphism because the threonine to serine substitution is conservative and the patient does not have diabetes.

Footnotes

Competing interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Bioulac‐Sage P, Rebouissou S, Sa Cunha A.et al Clinical, morphologic, and molecular features defining so‐called telangiectatic focal nodular hyperplasias of the liver. Gastroenterology 20051281211–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bluteau O, Jeannot E, Bioulac‐Sage P.et al Bi‐allelic inactivation of TCF1 in hepatic adenomas. Nat Genet 200232312–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zucman‐Rossi J, Jeannot E, Tran Van Nhieu J.et al Genotype‐phenotype correlation in hepatocellular adenoma: new classification and relationship with HCC. Hepatology 200643515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thysell H, Ingvar C, Gustafson T.et al Systemic reactive amyloidosis caused by hepatocellular adenoma. A case report. J Hepatol 19862450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fievet P, Sevestre H, Boudjelal M.et al Systemic AA amyloidosis induced by liver cell adenoma. Gut 199031361–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berthet B, Escoffier J M, Weiller P J.et al Inflammatory syndrome, anicteric cholestasis and hepatic adenoma. J Chir (Paris) 1993130297–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melin J P, Lecrique T, Wynckel A.et al Remission of nephrotic syndrome related to AA amyloidosis after hepatic adenomectomy. Nephron 199364157–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cosme A, Horcajada J P, Vidaur F.et al Systemic AA amyloidosis induced by oral contraceptive‐associated hepatocellular adenoma: a 13‐year follow up. Liver 199515164–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibasaki T, Matsumoto H, Watabe K.et al A case of renal amyloidosis associated with hepatic adenoma: the pathogenetic role of tumor necrosis factor‐alpha. Nephron 199775350–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delgado M A, Liu J Y, Meleg‐Smith S. Systemic amyloidosis associated with hepatocellular carcinoma. Case report and literature review. J La State Med Soc 1999151474–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]