Abstract

Background

The liver may have a role in peripheral tolerance, by serving as a site for trapping, apoptosis and phagocytosis of activated T cells. It is not known which hepatic cells are involved in these processes. It was hypothesised that liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC) which are strategically placed for participation in the regulation of sinusoidal blood flow, and express markers involved in recognition, sequestration and apoptosis, may contribute to peripheral tolerance by inducing apoptosis of activated T cells.

Methods

By using immunoassays and western blot analysis, the fate of activated T cells when incubated with human LSEC isolated from normal healthy livers was investigated.

Results

Evidence that activated (approximately 30%) but not non‐activated T cells undergo apoptosis on incubation with human LSEC in mixed cell cultures is provided. No difference in the results was observed when unstimulated and cytokine‐stimulated LSEC were used. T cell–LSEC contact is required for induction of apoptosis. Apoptosis induced by LSEC was associated with caspase 8 and 3 activity and strong expression of the proapoptotic molecule Bak. Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) produced constitutively by LSEC is partly responsible for the caspase‐induced apoptosis, as neutralising antibodies to TGFβ markedly attenuated apoptosis, up regulated the antiapoptotic molecule Bcl‐2 and partially blocked caspase‐3 activity.

Conclusion

These findings broaden the potential role of LSEC in immune tolerance and homeostasis of the immune system. This study may provide insight for exploring the mechanisms of immune tolerance by liver allografts, immune escape by some liver pathogens including hepatitis C and pathogenesis of liver diseases.

T cell apoptosis is important in the homoeostasis of the immune system. In fact, deletion of antigen‐specific T cells is considered to be one of the most important mechanisms in immune tolerance.1 Evidence suggesting that the liver is a specific site for the trapping and apoptosis of activated T cells is available.2 According to this model, the large numbers of activated T cells present at the end of an immune response do not undergo apoptosis diffusely throughout the immune system but are trapped in the liver, where they are induced to undergo apoptosis. This was shown using T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice injected with a specific peptide.3 The study documented the deletion of CD8+ cells from the periphery and their accumulation in the liver, where apoptosis occurred. Accumulation of apoptotic T cells in the liver has been shown in several other systems, including transplantation,4 transgenic models of peripheral tolerance5 and hepatitis C infection.6 How this tolerant state is achieved remains unclear, and various mechanisms involving peripheral deletion or suppression of alloreactive T cells have been proposed.7,8 Further, it is currently not known which cells in the liver take part in the tolerance‐inducing process.

Details regarding the liver's ability to establish tolerance are being elucidated only now. One of the principal findings is that liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC) are likely to be important in tolerance induction.9,10 LSEC, which represent about 60% of the non‐parenchymal cells of the liver, are strategically placed lining the hepatic sinusoid, and therefore become the first contact of tissue with circulating lymphocytes. LSEC possess fenestrations, and it is believed that the exchange of fluid, solutes and particles between the blood and space of Disse takes place through these open fenestrae. LSEC constitutively express high levels of adhesion molecules including intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)‐1, CD106 (vascular cell adhesion molecule‐1 (VCAM‐1)) and liver/lymph node‐specific ICAM‐3‐grabbing, non‐integrin (L‐SIGN) and vascular adhesion protein‐1 (VAP‐1),11,12,13 suggesting that they can potentially function as cells capable of trapping CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Thus, these cells are ideally located to interact with T lymphocytes in the sinusoids. We, 14,15 and others, 16 have shown that human LSEC constitutively produce high levels of the immunomodulatory cytokine transforming growth factor β (TFGβ). Further, galectin‐1, a lectin that is specifically expressed on LSEC in the liver,17 is known to bind to and induce apoptosis in activated T cells.18 These observations indicate that LSEC may potentially participate in the process of inducing T cell apoptosis in the liver.

The resolution of the cellular basis of trapping and the subsequent fate of the trapped T cells in the liver are important issues that will help understand the role of various hepatic cells in tolerance induction. To deal with this issue, we chose to investigate whether LSEC regulate apoptosis of activated T cells. As LSEC constitutively express high levels of several markers that are involved in recognition, sequestration and induction of apoptosis of activated cells and are strategically placed for participation in the regulation of sinusoidal blood flow, we hypothesised that these cells would be the ideal cell candidates of the liver responsible for the induction of apoptosis of activated T cells. In this study, using LSEC isolated from normal healthy livers, we investigated the fate of activated T cells when incubated with LSEC.

Materials and methods

Isolation and culture of LSEC

Human LSEC were isolated from the liver of a healthy liver donor using a method described earlier.14,15 The isolated cells were seeded on gelatin‐coated tissue‐culture flasks and grown in endothelial cell selective medium MCDB 131 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) with 10% heat‐inactivated human AB serum and supplemented with EGM‐2 singlequots (Cambrex Bio Science Walkersville Clonetics, Walkersville, Maryland, USA). LSEC in passages 3–4 were used for this study. Freshly–isolated cells, as well as LSEC from three additional healthy liver donors, were used to check for reproducibility of the results obtained in this study.

Primary human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) were purchased from Clonetics and cultivated in the same medium as used for LSEC. HAEC were used as control cells. Unstimulated and cytokine‐stimulated LSEC and HAEC were used for the experiments. Cytokine stimulation was performed for 16 h with recombinant human interferon (IFN)γ (200 ng/ml) and tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα; 20 ng/ml).

Consent was obtained from the Karolinska University Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Characterisation of LSEC

Flow cytometry was used to phenotypically characterise LSEC and HAEC. Primary antibodies used were unconjugated, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐conjugated or phycoerythrin‐conjugated:(anti‐CD31 (PECAM‐1) (FITC), Sigma‐Aldrich, Munich, Germany); (anti‐human leucocyte antigen‐class II (FITC), anti‐CD40 (FITC), anti‐CD54 (ICAM‐1) (phycoerythrin), BD Biosciences, San José, California, USA); (anti‐CD80, anti‐CD86, anti‐HLA‐class I (phycoerythrin), anti‐L‐SIGN, −vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFR)‐1 (FITC), R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK); (anti‐CD106 (VCAM‐1; FITC), anti‐CD62E (E‐selectin) (phycoerythrin), anti‐CD16 (FITC), anti‐CD14 (phycoerythrin), anti‐CD64 (phycoerythrin), anti‐CD32 (phycoerythrin), anti‐CD146 (phycoerythrin), anti‐CD11b, anti‐CD11c, anti‐CD95 (FITC), anti‐CD95L, anti‐Tie‐2 (FITC), −Galectin‐1, BD PharMingen, San Diego, California, USA); acetylated low‐density lipoprotein (Ac‐LDL) (FITC), Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon, USA); (anti‐CD105 (phycoerythrin), anti‐EPCAM (FITC) Serotec, Oxford, UK); (anti‐FVIIIRAg DakoPatts, Denmark); (anti‐VAP‐1B); (anti‐VEGFR‐2 Reliatec, Germany); (anti‐PDL‐1, anti‐PDL‐2, E‐biosciences, San Diego, California, USA). Anti‐fibroblast and smooth‐muscle cell (α‐actin) (Harlan Sera‐Lab, Loughborough, Leicestershire, UK) antibodies were also used. Cells were incubated with the primary antibodies for 30 min at room temperature and washed. The secondary antibody, goat anti‐mouse (1:10) (FITC, Jackson ImmunoResearch, Baltimore, Maryland, USA) was added and the cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C. Dead cells were excluded by staining with propidium iodide (BD PharMingen). Analysis of the cells was carried out in a flow cytometer and with the help of Cell Quest Software (Becton Dickinson, San José, California, USA).

Isolation and activation of T cells from peripheral blood

To elucidate the cellular interactions between LSEC and activated T cells, we used mitogen‐activated T cells. Non‐activated T cells were used as controls.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from normal healthy blood donors (n = 10) were separated over Ficoll gradient. CD3+ cells were isolated using magnetic beads coated with mouse anti‐human CD3 (DYNAL AS, Oslo, Norway) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the magnetic beads were detached using DETACHabeads. The following mitogens were used to stimulate T lymphocytes at final concentration of: concanvalin A (ConA) 10 μg/ml (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, UK) and phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) 10 μg/ml (Wellcome, Dartford, UK). Mitogens and T cells were cultured at 37°C in humidified 5% CO2 for three days.

Mixed cell cultures (MCCs)

Allogeneic PBMC were used as positive control. Irradiated (20 Gy) stimulator cells, LSEC or HAEC (100 000 cells/well) were added to 96‐well plates and allowed to adhere to the plastic. Responder cells—that is, non‐activated T cells, PHA or ConA activated CD3+ T lymphocytes (100 000 cells/well)—were then added. Cells were cultured in a total volume of 0.2 ml of complete RPMI 1640 medium. Cultures were set up in triplicate for each experiment and incubated at 37°C in humidified 5% CO2 for 72 h. Each stimulator cell type with RPMI 1640 medium only without responder cells was used as controls. Similarly, non‐activated and activated T cells with RPMI only were also included as controls. The culture wells were pulsed with 1 μCi/ml of 3[H]thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) on day 3 and cells were harvested using a harvester machine (Harvester 96, Tomec, Orange, Connecticut, USA) after 18 h to measure the thymidine incorporation on a glass filter (Wallac, Turku, Finland). Radioactivity was expressed as counts per minute (cpm) after being measured in a β‐counter (Wallac). Each experiment was repeated three to five times to ensure reproducibility of the results.

For the MCC experiments, each T cell–LSEC combination was performed with freshly isolated as well as three different primary cell lines of LSEC to ensure reproducible results.

Apoptosis detection assays

Annexin V‐FITC staining: For detection of apoptosis, non‐activated and activated T cells were cocultured with LSEC or HAEC, harvested after three days and stained with FITC‐conjugated annexin V and propidium iodide added at a final concentration of 50 μg/ml) (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To study which of the two populations underwent apoptosis, the annexin V+ cells were double stained with either anti‐CD3 or the endothelial cell marker CD146. The cells were analysed by flow cytometry.

Comet assay: Single‐cell gel electrophoresis or the comet assay was performed to demonstrate DNA damage in CD3+ apoptotic cells. The technique was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems). The slides were stained with SYBR green and examined using fluorescence microscopy.

Caspase activity assay: Non‐activated and activated CD3+ T cells at 24, 48 and 72 h after coculture with LSEC were tested for caspase activity. The activity of caspase 8 was determined by a caspase colorimetric assay kit, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Caspase 3 was detected by fluorescence‐activated cell sorter analysis in saponin (5%) permeabilised cells using anti‐caspase 3 antibody (R&D Systems).

Phenotypic characterisation of the apoptotic T cells

Table 1 shows the phenotypic characterisation of activated T cells and apoptotic T cells as described earlier using antibodies. T cells incubated with HAEC were also tested for the same apoptotic markers.

Table 1 Phenotypic characterisation of apoptotic T cells.

| Antibodies to | Activated T cells | Apoptotic T cells |

|---|---|---|

| CD45 | +++ | +++ |

| CD3 | +++ | + |

| CD4/CD8 | +++/+ | – |

| CD45RA | – | – |

| CD45Ro | + | +++ |

| TCRαβ | +++ | + |

| TCRγδ | ++ | + |

| CD25 | ++ | –/+ |

| CD95 | + | +++ |

| CD95L | + | +++ |

| CD40L | ++ | + |

TCR, T cell receptor.

Cytokine production in supernatants of the MCC

Supernatants from the cocultures of each of the responder and the stimulator cells were tested for the production of cytokines. The cell culture supernatants were collected after 72 h, sterile filtered and kept frozen at −70°C until assayed. Interleukin (IL)2, IL4, IL10, IFN‐γ, TNF‐α, and TGFβ were measured using the standard sandwich ELISA techniques using Quantikine sandwich enzyme immunoassay from R&D systems. Assays were performed according to the manufacture's instructions.

Transwell assay

To determine whether Tcell‐LSEC contact is required for induction of apoptosis in presence of LSEC, we performed transwell assays. LSEC were cultured on gelatin‐coated, 8‐μm pore size polycarbonate filters in tissue culture inserts of 6.5 (Transwell; Costar, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA) for at least five days with media changes every second day. When the endothelial cells had reached confluence, the tissue culture inserts were moved to a new six‐well plate. Approximately 1×106 non‐activated or activated T cells in 1000 μl of medium were added to the lower baskets, The viability of the cells were tested immediately before addition of the cells in the lower baskets. The cells were incubated for 0, 24, 48 or 72 h, after which the T cells in the lower chamber were stained with annexinV/PI for detection of apoptosis by flow cytometry. Each cell combination was carried out in triplicate, and mean values are given.

Blocking of apoptosis

As the cytokine results showed presence of high levels of the cytokine TGFβ. We tested whether anti‐TGFβ antibodies could block apoptosis of PHA or Con A‐activated T cells. Anti‐human TGFβ neutralising antibodies (R&D Systems) at different dilutions of 20, 30, and 50 μg/ml with or without General Caspase Inhibitor Z‐VAD‐FMK (R&D Systems 30 μM final concentration) were added to the MCC of T lymphocytes and LSEC. Neutralising TGFβ antibodies and Pan‐caspase inhibitor were added to the MCC at different time points—that is, at start, 24 h and 48 hrs of culture. An isotype control antibody (BD PharMingen) was used as a negative control. Cells were then analysed in the flow cytometer for annexin V positive cells.

Western blot analysis

CD3+ T cell lysates of untreated, apoptotic and from TGFβ blocked cell cultures (1×106) were immunoblotted with rabbit anti‐human Bak, Bax, BclXl/BclXs, (R&D Systems) mouse anti‐human Bcl‐2α, Biosource International, Camarillo, California, USA) (concentrations as recommended) using the standard sodium dodecyl sulphate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and western blots analysis. Horseradish peroxidase conjugated F(ab')2 fragments of donkey anti‐rabbit IgG, (1:10 000) (Amersham Biosciences AB, Uppsla, Sweden) and goat anti‐mouse IgG secondary monoclonal antibodies (1:5000; Jackson Immunoresearch) were used. Secondary antibody with protein blots served as negative controls. Antibody‐binding components were detected using the ECL kit (Amersham). Chemiluminescence was detected using a Fluor‐S Max (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, California, USA) equipped with a CCD camera operating at −35°C. Determination of the molecular mass of the target proteins was done using ECL DualVue Western Blotting Markers (Amersham Biosciences).

Immunohistochemistry for detection of TGFβ in LSEC in biopsy sections from normal livers

Liver biopsy specimens taken from normal healthy livers (n = 5) were snap frozen in liquid N2 and stored in −70°C. Immunohistochemistry was performed by single and double immunostaining, as described earlier15 using monoclonal antibodies against DC‐SIGN2 also called L‐SIGN, an antibody specific for LSEC (liver/lymph node‐specific ICAM‐3‐grabbing non‐integrin; R&D Systems), and/or anti‐TGFβ antibodies (R&D Systems).

Real‐time polymerase chain reaction

A total of 2.5 μl of cDNA from freshly isolated and passage 4 from all three primary LSEC lines were used in a 25 μl of reaction containing 1× SYBR (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) and 300 nM of each primer. Primer sequences were TGFβ‐F: 5′‐GGA AAC CCA CAA CGA AAT CTA TG‐3′, TGFβ‐R″: 5′‐CGC CAG GAA TTG TTG CTG TA‐3′. The polymerase chain reaction was performed and analysed as described previously.14

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean (standard error of the mean (SE)). A p value of <0.05 was considered to be significant. Correlations were performed by the Spearman's rank test. Differences were analysed by analysis of variance using Kruskal–Wallis test and followed by Dunett's test. The statistical analysis was performed using statistical software SAS V.9.1.3 (SAS Campus Drive, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

The unique phenotype of LSEC

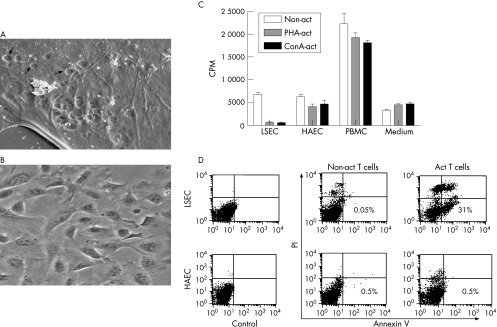

We have previously isolated and characterised LSEC in our laboratory from several healthy normal livers.14,15 For this study, we freshly isolated LSEC from three different normal healthy livers and confirmed the unique phenotype of the isolated LSEC using electron microscopy and flow cytometry. All three primary cell cultures of LSEC showed the same phenotype (table 2; figs 1A, B) and gave similar results. Scanning electron microscopy showed the presence of fenestrae characteristic for LSEC as published by us earlier.14 It is important to mention that the phenotype of cultured LSEC in passages 3–4 was similar to that of freshly isolated LSEC.

Table 2 Phenotypic markers expressed by human liver sinusoidal and human aortic endothelial cells.

| Antibodies to | Unstimulated LSEC (n = 3) | Stimulated LSEC (n = 3) | Unstimulated HAEC (n = 2) | Stimulated HAEC (n = 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endothelial markers | ||||

| CD31 | – | – | ++ | ++ |

| Ac‐LDL | ++ | ++++ | ++ | +++ |

| FVIIIRAg | – | – | ++ | ++ |

| CD105 | +++ | +++ | + | + |

| CD106 | – | +++ | – | ++ |

| CD62E | – | – | + | ++ |

| VEGFR‐2 | +++ | +++ | –/+ | + |

| VEGFR‐1 | ++ | ++ | –/+ | + |

| Tie‐2 | ++ | +++ | –/+ | –/+ |

| CD146 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| Immune recognition markers | ||||

| HLA class II | – | +++ | – | ++ |

| CD80 | – | – | – | – |

| CD86 | – | – | – | – |

| CD40 | – | ++ | – | + |

| HLA class I | +++ | ++++ | +++ | ++++ |

| ICAM‐1 | +++ | ++++ | + | ++ |

| CD11b | ++ | +++ | – | – |

| CD11c | ++ | +++ | – | – |

| L‐SIGN | ++ | ++ | – | – |

| VAP‐1 | ++ | ++ | – | – |

| Apoptosis‐associated markers | ||||

| Galectin‐1 | +++ | ++++ | – | – |

| CD95 | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| CD95L | – | – | – | – |

| PDL‐1 | ++ | +++ | – | – |

| PDL‐2 | ++ | +++ | – | – |

| Phagocytic markers | ||||

| CD14 | +++ | +++ | – | – |

| CD16 | ++ | ++ | – | – |

| CD32 | ++ | ++ | – | – |

| CD64 | – | – | – | – |

| Control markers | ||||

| Fibroblast Ag | – | – | – | – |

| α‐actin | – | – | – | – |

| EPCAM | – | – | – | – |

Ac‐LDL, acetylated low‐density lipoprotein; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; LSEC, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells; HAEC, human aortic endothelial cells; VAP, vascular adhesion protein; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor; +, weak or inconsistent staining; ++, moderate staining; +++, strong staining; ++++, very strong staining.

Figure 1 Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC) do not support proliferation of activated T cells. (A) Scanning electron micrograph showing LSEC cultured in transwell tissue culture inserts displaying fenestrations (arrowheads) in the cytoplasm. Bar = 1 μm. (B) Phase contrast picture of subcultured LSEC in passage 4. (C) Phytohaemagglutinin‐activated (PHA‐act; grey bars), concanvalin A‐activated (conA‐act; black bars) T cells but not non‐activated T cells (non‐act; empty bars) when cocultured with LSEC showed the least proliferative capacity as compared with coculture with human aortic endothelial cells or allogeneic peripheral blood lymphocytes. Data represent the mean (SEM) of triplicate wells of a tissue culture plate and are representative of at least five experiments. (D) Fluorescence‐activated cell sorter analysis at 72 h of non‐activated and PHA‐activated CD3+ cells after coculture with LSEC or HAEC show significantly increased positive staining for annexin V only in activated (Act) T cells cocultured with LSEC.

No proliferation of activated T cells when cocultured with LSEC

No significant difference in the results was obtained using unstimulated or stimulated LSEC/HAEC. We therefore only present results using cytokine‐stimulated LSEC/HAEC.

We found that thymidine uptake was the least in the MCC of activated T cells and LSEC (1500 (590) CPM). The CPM were significantly higher in MCC with HAEC (5000 (735); p<0.001), or human PBMC (20 000 (2220); (p<0.001; fig 1C). In addition, the CPM was also higher in the MCC of non‐activated T cells and LSEC (6500 (527)). The CPMs for proliferation of non‐activated and activated T cells alone were 3500 (856) and 4200 (740), respectively. As the numbers of proliferating cells in MCC using LSEC were repeatedly and consistently low as compared with the HAEC, we suspected cell death in this culture combination. Only activated T cells underwent increased apoptosis as detected by annexin V staining after coculture with LSEC as compared with HAEC (fig 1D). However, non‐activated T cells did not undergo apoptosis when co‐cultured with either LSEC or HAEC (fig 1D).

Apoptosis of activated T cells in MCC using LSEC

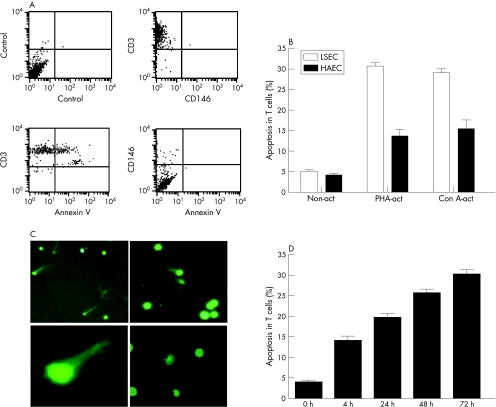

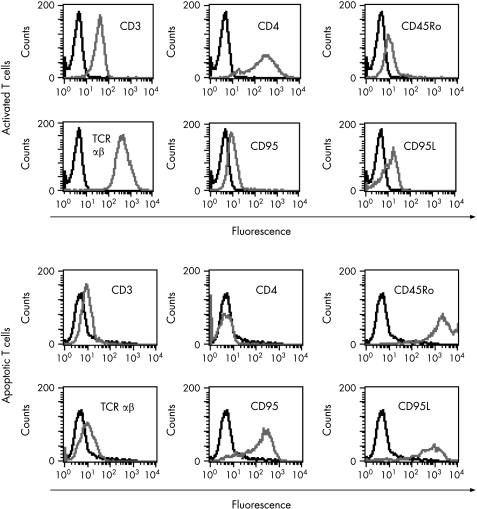

We initially checked to see which of the two cell populations (T lymphocytes or LSEC) were apoptotic. Double staining of CD3+ or CD146+ cells from the MCC with annexin V, indicated that it was the CD3+ population that was apoptotic (fig 2A). A few of the adherent LSEC (<1%) were found to have detached from the plastic and were observed in the supernatants of the MCC. However, these cells were not annexin V+ (fig 2A). Staining of T cells from the various MCC, with annexin V/PI showed that a significantly higher population of the activated T cells cocultured with LSEC were ann V+/PI− as compared with the non‐activated T cells and those cocultured with HAEC (p<0.001; fig 2B). On average, approximately 30% of activated peripheral T cells underwent apoptosis (28.5% (6.4%)) when cultured with stimulated LSEC. Spontaneous apoptosis of non‐activated and activated T cells at 72 h were 5% (1%) and 7% (2%), respectively. In addition, significantly, higher numbers (26% (8.3%)) of apoptotic T cells from the MCC of LSEC showed the typical shape of a comet with elongated tails of DNA as compared with the non‐activated control T cells (5% (1.2%)) which had rounded intact nuclei (fig 2C, p<0.01). Time kinetics of the T cell apoptosis using PHA‐activated CD3+cells cocultured with LSEC indicated that 15% of T cells were already apoptotic (ann v+/PI−) after 4 h (fig 2D). Activation of T cells by PHA and Con A was confirmed by the expression of various activation markers such CD95L and CD25 (table 1, fig 3) which were not expressed by the non‐activated T cells (data not shown). Phenotypic characterisation of the apoptotic T cells showed down regulation of the TCR and CD4 receptors, but high expression of CD45RO, CD95 and CD95L markers (table 1, fig 3). Approximately, 5% of the activated T cells undergoing apoptosis were TCR γδ+. A similar apoptotic T cell phenotype was not observed in cells collected from Tcells/HAEC cultures.

Figure 2 Apoptosis of activated T cells (annexin V (annV)+/PI− cells) by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC). (A) Double staining of CD3+ or CD146+ cells from the mixed cell cultures with ann V, indicated that it was the CD3+ population that was apoptotic. A few of the adherent LSEC (<1%) were found to have detached from the plastic and were observed in the supernatants of the mixed cell culture. However, these cells were not annV+. (B) Significantly (30%) higher numbers of phytohaemagglutinin‐activated (PHA‐act) and concanvalin A‐activated (ConA‐act) CD3+ cells undergo apoptosis when incubated with LSEC (empty bar) but not with human aortic endothelial cells (solid bar; p<0.001). Cells were stained with annexin V and propidium iodide to detect apoptotic cells and were analysed by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean (SEM) of five experiments. (C) Single‐cell gel electrophoresis or the comet assay was performed to show DNA damage in apoptotic cells. SYBR green was used to visualise the comets. Apoptotic activated T cells (upper panel) showed the typical shape of a comet with elongated tails of DNA (higher magnification, lower left panel), whereas the non‐activated T cells have rounded intact nuclei (lower right panel). (D) Time kinetics of activated T cell apoptosis (annV+/PI−).

Figure 3 Flow cytometric analysis was performed to detect differences in the phenotype of activated (A) and apoptotic (B) T cells. Apoptotic T cells showed down regulation of the T cell receptor (TCR) and CD4 receptors, but high expression of CD45RO, CD95 and CD95L.

We next tested the presence of cytokines in the MCC to identify a possible soluble factor responsible for induction of apoptosis. We tested for some inflammatory cytokines as well as cytokines that are known to have immunomodulatory effects.

High levels of TGFβ in the activated T cell‐LSEC MCC

At 72 h, we found high mean (SEM) levels of TGFβ1 (870 (130) pg/ml) constitutively produced by LSEC and the levels of TGFβ1 were further significantly increased in the MCC supernatants of activated T cells with LSEC (1393 (90) pg/ml; table 3). However, non‐activated or activated T cells alone did not produce high levels of TGFβ1 (85 (30) pg/ml, 198 (40) pg/ml, respectively). Further, no increased levels of TGFβ1 were found in the MCC cultures of activated T cells and HAEC (table 3). The levels of other cytokines were negligible in these MCC supernatants <30 pg/ml. However, levels of IFNγ were significantly higher in MCC with allogeneic lymphocytes (positive control) 900 (110) pg/ml compared with (30 (8) pg/ml) in MCC with LSEC.

Table 3 Cytokine detection in supernatants of non‐activated, Ni‐activated and mitogen‐activated T cells cocultured with allogeneic liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and human aortic endothelial cells.

| Cytokine (pg/ml) | Stim* LSEC | Non‐act T cells | PHA‐act T cells | Non‐act T cells /stim LSEC | PHA‐act T cells /stim LSEC | Stim* HAEC | Non‐act T cells /stim HAEC | PHA‐act T cells /stim HAEC | PHA‐act T cells /PBMC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGFβ | 870 (130) | 85 (30) | 198 (40) | 710 (30) | 1393 (90) | 454 (170) | 320 (50) | 483 (150) | 116 (72) | ||

| IFNγ | 46 (10) | <30 | <30 | 790 (190) | 115 (53) | 43 (5) | 670 (60) | 152 (76) | 900 (110) |

Act, activated; IFN, interferon; LSEC, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PHA, phytohaemaglutinin; stim, stimulated; TGF, transforming growth factor.

Values are mean (SEM).

*No significant difference in constitutive levels of TGFβ was observed with unstimulated or cytokine stimulated LSEC or human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC). Cytokine stimulation of LSEC and HAEC was performed for 16 h with recombinant human IFN γ (200 ng/ml) and tumour necrosis factor α (20 ng/ml).

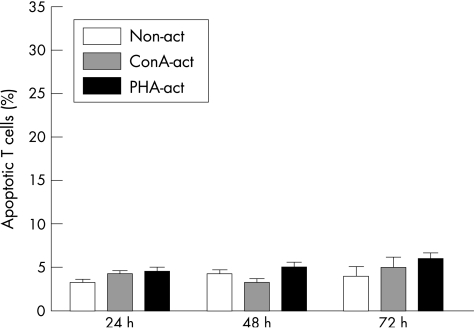

T cell–LSEC contact is required for induction of apoptosis

In the transwell assays, we found few activated T cells (5% (1%)) that were annV+/PI− when cultured in the lower chamber as compared with 4% (1%) in the non‐activated T cell population at 24 h (fig 4). At 72 h, 7% (2%) of activated T cells were ann+/PI−, as compared with 5% (1%) in the non‐activated T cells. This indicated that activated T cells required contact with LSEC in order to undergo apoptosis.

Figure 4 In transwell experiments, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC) were cultured in the upper chamber and T cells were added to the lower chamber and incubated for 24, 48 and 72 h. The results indicated that CD3+ non‐activated (non‐act) or activated (ConA‐act) T cells do not undergo apoptosis when not in direct contact with LSEC. Data represent the mean (SEM) of three experiments.

LSEC induced apoptosis activates caspase 8 and 3

We investigated caspases 8 and 3‐specific activities in activated T cells undergoing apoptosis when cocultured with LSEC. LSEC induced caspase 8 and 3 activities in the apoptotic T cells as shown by a colorimetric enzyme assay and a flow cytometric method, respectively. The colorimetric assay of caspase activity revealed that caspase 8 activity was the highest at 24 h, giving mean (SD) optical density values of 0.3 (0.02) (24 h, threefold increase), 0.22 (0.01) (48 h, 2.2‐fold increase) and 0.15 (0.01) (72 h, 1.5‐fold increase) after coculture of activated T cells with LSEC as compared with the control (0.01 (0.001)). We found that approximately 27% (3%) T cells were caspase 3 positive at 72 h after coculture with LSEC (fig 5A).

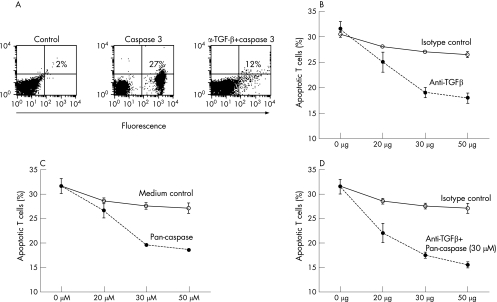

Figure 5 Transforming growth factor (TGF)β produced by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC) induce apoptosis in activated T cells (annV+/PI− cells). (A) A representative fluorescence‐activated cell sorter dot plot of apoptotic cells staining positive with a caspase 3 antibody (27%) after coculture of activated T cells with LSEC. Neutralising TGFβ antibodies (30 μg/ml) added to the mixed cell culture with LSEC reduced the number of caspase 3 positive cells (12%). (B,C) Neutralising TGFβ antibodies or pan‐caspase inhibitor (Z‐VAD‐FMK) blocked the apoptosis induced by (LSEC) (•). An isotype‐matched antibody was used as a control (o). (D) The blocking of apoptosis was not further increased when the pan‐caspase inhibitor was added with the neutralising TGFβ antibodies (•). Data represent the mean (SEM) of three experiments.

Neutralising TGFβ antibodies partially decreased T cell apoptosis

We found that the apoptosis of T lymphocytes was significantly blocked (approximately 50%) when neutralising anti‐TGFβ1 antibodies, as compared with the isotype control, were added at the start of the MCC of activated T cells with LSEC (fig 5B, table 4). The apoptosis was also blocked using a pan‐caspase inhibitor (Z‐VAD‐FMK; fig 5C). Blocking with TGFβ antibodies together with the pan‐caspase inhibitor (30 μmol/l) did not further decrease apoptosis (fig 5D, table 4). Addition of the neutralising antibodies or the pan‐caspase inhibitor at any time point after the start of MCC did not block apoptosis. Even though T cell apoptosis was partially decreased by the anti‐TGFβ1 antibodies, no proliferation of T cells was observed.

Table 4 Blocking of apoptosis with only anti‐transforming growth factor β antibodies or in combination with a general pan‐caspase inhibitor.

| % ANN+/PI− T cells—no blocking | % ANN+/PI− T cells after blocking with 30 μg/ml isotype control | % ANN+/PI−T cells after blocking with 30 μg/ml TGFβ Abs | % ANN+/PI− T cells after blocking with 30 μM/ml PC | % ANN+/PI− T cells after blocking with 30 μg/ml TGFβ abs+30 μM/ml PC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHA‐activated | 31 (4)* | 30 (3) | 14 (4)* | 24 (3)* | 16 (3)* |

| ConA‐activated | 34 (2)* | 29 (4) | 17 (6)* | 19 (4)* | 17 (3)* |

Abs, antibodies; ANN, annexin; ConA, concanavalin A; PC, pan‐caspase; PHA, phytohaemagglutinin; PI, propidium iodide; TGF, transforming growth factor.

Values are mean (SEM).

*p<0.01.

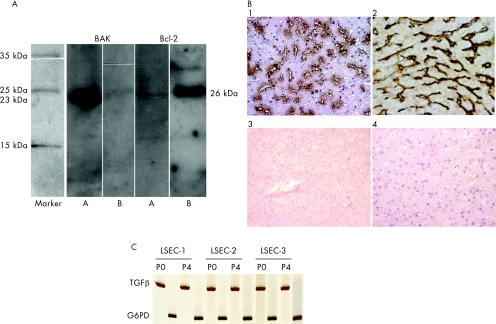

Further, the addition of neutralising TGFβ1 antibodies decreased the mean (SEM) percentage of T cells positive for caspase 3 (14% (4%); fig 5A) and strongly down regulated the proapoptotic molecule Bak and up regulated the antiapoptotic molecule Bcl‐2 (fig 6A). No change in the expressions of Bax or BclXl/BclXs was observed (data not shown).

Figure 6 (A) Western blotting analysis indicated that apoptosis (T cell lysates from 1×106 cells) was associated with increased expression of the proapoptotic protein Bak (23 kDa) but not Bcl‐2 (26 kDa; lanes A), while blocking with neutralising transforming growth factor (TGF)β antibodies decreased Bak but increased Bcl‐2 expression in the T cells cocultured with liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC; lanes B). (B) Enzyme staining of normal liver sections with TGFβ antibodies showed that a large number LSEC together with Kupffer cells stain positively with the antibodies (brown) (1), double staining with anti‐liver/lymph node‐specific ICAM‐3‐grabbing, non‐integrin (L‐SIGN; black), a marker specific for LSEC and anti‐TGFβ (brown) antibodies, clearly showed that TGFβ is also produced by LSEC (2). Secondary conjugated antibodies served as controls (3 and 4). Magnification 1, 2 and 4, ×40, 3, ×20. (C) mRNA for TGFβ was detected in freshly isolated (P0) and subcultured (P4) LSEC from three different healthy liver donors.

TGFβ in LSEC

We found that the anti‐TGFβ antibody strongly stained (brown staining) both LSEC and Kupffer cells in liver biopsy sections taken from normal healthy livers (n = 5; fig 6B). To further demonstrate TGFβ in LSEC, we double stained with anti‐L‐SIGN (black staining) and anti‐TFGβ (brown staining) antibodies. In addition, mRNA for TGFβ was detected in both freshly isolated and subcultured LSEC (fig 6C).

Discussion

The liver is considered a site for trapping, apoptosis and phagocytosis of activated T cells. In fact, the accumulation and apoptosis of activated CD8+ T cells in the liver during systemic immune responses have been reported.19,20 In this study, we provide evidence that LSEC may be one of the major cell types in the liver that contribute to peripheral tolerance by the induction of apoptosis of the activated T cells.

The phenotypic analysis of LSEC isolated from various healthy livers showed that these cells constitutively express high levels of markers such as ICAM‐1, VCAM‐1, galectin‐1, CD11b, CD11c and VAP‐1 all of which suggest that these cells may be involved in trapping of activated T lymphocytes. Using coculture studies, we showed that approximately 30% of activated, but not non‐activated, T cells undergo apoptosis on interaction with LSEC (activated or non‐activated). No significant apoptosis was observed when non‐activated or activated T cells were cocultured with vascular endothelial cells such as HAEC (activated or non‐activated). This distinctive population of apoptotic T cells expressed low levels of TCR αβ, no CD4 or CD8, but high levels of CD45RO, CD95 and CD95L. Apoptotic T cell populations with a similar abnormal phenotype have been described to accumulate specifically in the liver.21 Importantly, using transwell assays, we further demonstrate that activated T cells do not undergo apoptosis when not in direct contact with LSEC. As only a fraction (approximately 30%) of the activated T cells and not all activated T cells undergo apoptosis, it is possible that contact with LSEC may induce a phenotypic change in activated T cells that are already programmed for cell death.

Although LSEC express several candidate molecules that might be involved in inducing apoptosis, we were interested in investigating the role of TGFβ in this process, as we have reported previously that LSEC constitutively produce high levels of this cytokine.14,15 We found that the TGFβ levels in cocultures of activated T cells/LSEC were further increased above the constitutive levels produced by LSEC. Interestingly, increased levels of TGFβ were not observed in cocultures of non‐activated T cells and LSEC. We also confirmed the expression of TGFβ in LSEC by staining liver biopsy sections from several different normal healthy liver donors with an anti‐TGFβ antibody. Induction of apoptosis via TGFβ starts early after activated T cell interaction with LSEC. Several apoptotic cells were observed after 4 h and numbers steadily increased within the next 24–48 h. As even non‐activated LSEC triggered apoptosis in a fraction of activated T cells, it is tempting to speculate that this may be a primary function of LSEC. Addition of exogenous human TGFβ (10 ng/ml) to T cell/HAEC cultures did not induce apoptosis or suppress proliferation (data not shown), indicating that the apoptosis‐inducing function may be restricted to LSEC.

TGFβ is a multifunctional growth factor involved in the regulation of proliferation, extracellular matrix production and degradation, cell differentiation and apoptosis induction.22 TGFβ signalling results from the interaction of TGFβ with its cell–surface receptors type I (TGFβRI) and type II (TGFβRII), which allows for recognition by TβRI. Once recognised, a stable ternary complex forms and the TGFβ signalling pathways are initiated by the mutual phosphorylation of TGFβRI and TGFβRII, both of which are serine/threonine kinases.22 The Smad proteins function as the intracellular effector molecules that transduce the TGFβ signal from the membrane to the nucleus, and this intracellular signalling pathway has been well studied.23,24 TGFβ‐induced apoptosis can also occur via the release of cytochrome c and the subsequent oligomerisation of apoptotic protease‐activating factor 1, which initiates the caspase cascade.25 We found caspase 8 and 3 activity in the apoptotic T cell lysates, indicating a role for caspases in the apoptosis of T cells induced by LSEC. Further, neutralising TGFβ antibodies also blocked, albeit limited, some caspase 3 activity. However, blocking with a general caspase inhibitor did not completely attenuate apoptosis, implicating additional caspase‐independent mechanisms of apoptosis by LSEC. In this study, apoptosis of T cells was associated with up regulation of the proapoptotic molecule Bak. Bak is required for commitment to cell death.26 When activated, it can permeabilise the outer membrane of mitochondria and release proapoptogenic factors (eg, cytochrome c) needed to activate the caspases that dismantle the cell.26 Whereas cell death is promoted by Bax and Bak, cell survival is promoted by Bcl‐2 and several close relatives.27 This is shown in this study by the up regulation of Bcl‐2 and down regulation of Bak in T cells isolated from T/LSEC cell cultures blocked with anti‐TGFβ antibodies, indicating that TGF‐β induces apoptosis by down regulating Bcl‐2 and up regulating Bak. This is in contrast with the findings of Sillett et al,28 who reported that in post‐activated T cells TGFβ had no direct effects on the Bcl proteins.

The fact that only approximately 50% of the activated T cells are rescued from apoptosis by anti‐TGFβ antibodies indicates that LSEC may induce cell death by additional pathways, which may be TGFβ and caspase‐independent. We have observed strong cell–surface expression of the molecules‐programmed death ligands 1 and 2 (PDL‐1 and 2) and galectin‐1 on LSEC molecules that were absent on HAEC. We are currently elucidating the role of these molecules in immune responses mediated by LSEC. Interestingly, addition of neutralising TGFβ antibodies to MCC increased the levels of IFNγ in the supernatants. It is suggested that TGFβ promotes the passive cell death of post‐activated T cells by increasing their cytokine dependence, and addition of exogenous IL2 can abolish the proapoptotic effects of TGFβ.28 However, exogenous addition of IFN γ or IL2 at various concentrations did not abrogate T cell apoptosis in our study (data not shown), indicating that TGFβ may induce apoptosis by additional mechanisms. Thus, one mechanism by which LSEC may induce apoptosis of activated T cells is via secretion of the immunosuppressive cytokine TGFβ. Further, apoptotic T cells themselves can also secrete TGFβ and thereby contribute to the immunosuppressive milieu of the liver.29 However, our data also suggest that LSEC may induce T cell deletion via additional, possibly multiple mechanisms.

It has been shown that liver‐specific trapping of activated T cells favours CD8+ cells. However, this bias is not absolute. Both CD4+ and CD8+ populations of intrahepatic lymphocytes are enriched for memory/effector cells.20 In addition, the systemic activation of T cell receptor transgenic CD4+ cells leads to their redistribution into many organs, including the liver,30 and both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are recruited to the liver during liver damage.31,32,33 In our in vitro work using human LSEC, we have not noticed a preferential induction of apoptosis in only CD8+ T cells. In this study, we used CD4+ T cell clones to demonstrate this point.

Thus, LSEC may be one of the major cell types in the liver that actively participates in peripheral T cell deletion and in the homoeostasis of the immune system, using multiple mechanisms. Recent developments in the field of liver biology indicate that the LSEC are emerging as a cell type that has a central role in several biological processes. This is reflected by their (a) strategic location in the liver sieve which permits free contact of blood with hepatocytes, (b) innate scavenger capacity to endocytose and clear large particles, (c) specialised morphology and phenotype that enables trapping, apoptosis and antigen presentation to activated and naive T cells.34 Therefore, mechanical, chemical or immunological damage to LSEC may compromise these important biological functions leading to severe clinical disorders.

In short, the data in our study have clearly broadened the potential role of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells in immune tolerance. The present study may provide insight for exploring the mechanisms of immune tolerance by liver allografts immune escape by some liver pathogens including hepatitis C, and pathogenesis of liver diseases.

Abbreviations

Con A - concanvalin A

FITC - fluorescein isothiocyanate

HAEC - human aortic endothelial cells

ICAM - intercellular adhesion molecule

IFNγ - interferon γ

LSEC - liver sinusoidal endothelial cells

L‐SIGN - liver/lymph node‐specific ICAM‐3‐grabbing, non‐integrin

MCC - mixed cell culture

PBMC - peripheral blood mononuclear cells

PHA - phytohaemagglutinin

TCR - T cell receptor

TGFβ - transforming growth factor β

VAP - vascular adhesion protein

VCAM - vascular cell adhesion molecule

VEGF - vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Funding: This study was financed by grants from the Lars Erik Gelins Foundation and The Swedish Research Council number K2004‐06X‐14004‐02B (SS‐H) and Bengt Ihres foundation, Grönbergs foundation, “9 meter of life” (UB).

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Lenardo M, Chan K M, Hornung F.et al Mature T lymphocyte apoptosis—immune regulation in a dynamic and unpredictable antigenic environment. Annu Rev Immunol 199917221–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.John B, Crispe I N. Passive and active mechanisms trap activated CD8+ T cells in the liver. J Immunol 20041725222–5229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang L, Soldevila G, Leeker M.et al The liver eliminates T cells undergoing antigen‐triggered apoptosis in vivo. Immunity 19941741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qian S, Lu L, Fu F.et al Apoptosis within spontaneously accepted mouse liver allografts: evidence for deletion of cytotoxic T cells and implications for tolerance induction. J Immunol 19971584654–4661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertolino P, Heath W R, Hardy C L.et al Peripheral deletion of autoreactive CD8+ T cells in transgenic mice expressing H‐2Kb in the liver. Eur J Immunol 1995251932–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nuti S, Rosa D, Valiante N M.et al Dynamics of intra‐hepatic lymphocytes in chronic hepatitis C: enrichment for Valpha24+ T cells and rapid elimination of effector cells by apoptosis. Eur J Immunol 1998283448–3455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamada N, Davies H S, Roser B. Reversal of transplantation immunity by liver grafting. Nature 1981292840–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang R, Liu Q, Grosfeld J L.et al Intestinal venous drainage through the liver is a prerequisite for oral tolerance induction. J Pediatr Surg 1994291145–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Limmer A, Ohl J, Kurts C.et al Efficient presentation of exogenous antigen by liver endothelial cells to CD8+ T cells results in antigen‐specific T‐cell tolerance. Nat Med 200061348–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knolle P A, Limmer A. Neighborhood politics: the immunoregulatory function of organ‐resident liver endothelial cells. Trends Immunol 200122432–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams D H, Hubscher S G, Shaw J.et al Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 on liver allografts during rejection. Lancet 198921122–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bashirova A A, Geijtenbeek T B, van Duijnhoven G C.et al A dendritic cell‐specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3‐grabbing nonintegrin (DC‐SIGN)‐related protein is highly expressed on human liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and promotes HIV‐1 infection. J Exp Med 2001193671–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNab G, Reeves J L, Salmi M.et al Vascular adhesion protein 1 mediates binding of T cells to human hepatic endothelium. Gastroenterology 1996110522–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu B, Broome U, Uzunel M.et al Capillarization of hepatic sinusoid by liver endothelial cell‐reactive autoantibodies in patients with cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis. Am J Pathol 20031631275–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sumitran‐Holgersson S, Ge X, Karrar A.et al A novel mechanism of liver allograft rejection facilitated by antibodies to liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. Hepatology 2004401211–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bissell D M, Wang S S, Jarnagin W R.et al Cell‐specific expression of transforming growth factor‐beta in rat liver. Evidence for autocrine regulation of hepatocyte proliferation. J Clin Invest 199596447–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lotan R, Belloni P N, Tressler R J.et al Expression of galectins on microvessel endothelial cells and their involvement in tumour cell adhesion. Glycoconj J 199411462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perillo N L, Pace K E, Seilhamer J J.et al Apoptosis of T cells mediated by galectin‐1. Nature 1995378736–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehal W Z, Juedes A E, Crispe I N. Selective retention of activated CD8+ T cells by the normal liver. J Immunol 19991633202–3210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crispe I N, Dao T, Klugewitz K.et al The liver as a site of T‐cell apoptosis: graveyard, or killing field? Immunol Rev 200017447–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crispe I N. CD4/CD8‐negative T cells with alpha beta antigen receptors. Curr Opin Immunol 19946438–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wrana J L, Attisano L, Wieser R.et al Mechanism of activation of the TGF‐beta receptor. Nature 1994370341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hata A, Shi Y, Massague J. TGF‐beta signaling and cancer: structural and functional consequences of mutations in Smads. Mol Med Today 19984257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Derynck R, Zhang Y, Feng X H. Smads: transcriptional activators of TGF‐beta responses. Cell 199895737–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freathy C, Brown D G, Roberts R A.et al Transforming growth factor‐beta(1) induces apoptosis in rat FaO hepatoma cells via cytochrome c release and oligomerization of Apaf‐1 to form a approximately 700‐kd apoptosome caspase‐processing complex. Hepatology 200032750–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danial N N, Korsmeyer S J. Cell death: critical control points. Cell 2004116205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green D R, Kroemer G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science 2004305626–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sillett H K, Cruickshank S M, Southgate J.et al Transforming growth factor‐beta promotes ‘death by neglect' in post‐activated human T cells. Immunology 2001102310–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen W, Frank M E, Jin W.et al TGF‐beta released by apoptotic T cells contributes to an immunosuppressive milieu. Immunity 200114715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pape K A, Kearney E R, Khoruts A.et al Use of adoptive transfer of T‐cell‐antigen‐receptor‐transgenic T cell for the study of T‐cell activation in vivo. Immunol Rev 199715667–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Z X, Govindarajan S, Okamoto S.et al Fas‐mediated apoptosis causes elimination of virus‐specific cytotoxic T cells in the virus‐infected liver. J Immunol 20011663035–3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haydon G, Lalor P F, Hubscher S G.et al Lymphocyte recruitment to the liver in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol 20022729–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Q, Cao J S, Zhang X M. Liver‐infiltrating T lymphocytes cause hepatocyte damage by releasing humoral factors via LFA‐1/ICAM‐1 interaction in immunological liver injury. Inflamm Res 20025144–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knolle P A, Schmitt E, Jin S.et al Induction of cytokine production in naive CD4(+) T cells by antigen‐presenting murine liver sinusoidal endothelial cells but failure to induce differentiation toward Th1 cells. Gastroenterology 19991161428–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]