Abstract

Background and aims

Fractalkine, a chemokine that presents as both a secreted and a membrane‐anchored form, has been described as having tumour‐suppressive activities in standard subcutaneous models. Here, we investigate the antitumour effect of fractalkine, in its three molecular forms, in two orthotopic models of metastatic colon cancer (liver and lung) and in the standard subcutaneous model.

Methods

We have developed models of skin tumours, liver and pulmonary metastasis and compared the extent of tumour development between C26 colon cancer cells expressing either the native, the soluble, the membrane‐bound fractalkine or none.

Results

The native fractalkine exhibits the strongest antitumour effect, reducing the tumour size by 93% in the skin and by 99% in the orthotopic models (p<0.0001). Its overall effect results from a critical balance between the activity of the secreted and the membrane‐bound forms, balance that is itself dependent on the target tissue. In the skin, both molecular variants reduce tumour development by 66% (p<0.01). In contrast, the liver and lung metastases are only significantly reduced by the soluble form (by 96%, p<0.002) whereas the membrane‐bound variant exerts a barely significant effect in the liver (p = 0.049) and promotes tumour growth in the lungs. Moreover, we show a significant difference in the contribution of the infiltrating leukocytes to the tumour‐suppressive activity of fractalkine between the standard and the orthotopic models.

Conclusions

Fractalkine expression by C26 tumour cells drastically reduces their metastatic potential in the two physiological target organs. Both molecular forms contribute to its antitumour potential but exhibit differential effects on tumour development depending on the target tissue.

Keywords: colon cancer, immunotherapy, metastasis, chemokine, animal model

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in Western countries.1 Approximately one half of all patients develop metastases, especially in the liver and lung, which are the major cause of death. Fractalkine (FKN, CX3CL1) is a chemokine described for its tumour‐suppressive activity in various cancer models of subcutaneous implantation in the mouse.2,3,4 In a recent study by Ohta et al.,5 high expression of FKN was found to be a marker of better prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Unlike other chemokines existing as a soluble chemoattractant form6 (except CXCL16), FKN exists both as a membrane‐anchored molecule and as a secreted form that results from proteolytic cleavage.7 Interestingly, both forms exert specific effects on leukocytes because soluble FKN is reported to recruit lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells and dendritic cells7, whereas membrane‐bound FKN induces firm leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells under physiological flow.8 Despite evidence suggesting a role for soluble FKN in regulating leukocyte recruitment to the tumour site, the respective contribution of both forms of FKN to its tumour‐suppressive effect has not been elucidated. Previous studies have shown that the antitumour immune response elicited by FKN gene transfer into murine lung or colon carcinoma and lymphoma cell lines implanted subcutaneously depends on NK cells, dendritic cells and T‐cells.2,3,4,9 However, because of the heterogeneity of tumour types, target organs and the contribution of multiple immune‐escape mechanisms, working with orthotopic cancer models might be most suited to investigate new immunotherapeutic approaches. Therefore, we have examined the roles of native, soluble and membrane‐bound FKN in restricting tumour growth by using three distinct murine colon carcinoma models (subcutaneous, liver and lung). Our findings provide further insight into the immunotherapeutic potential of FKN in metastatic colon cancer and underscore the importance of using relevant animal models to investigate novel anti‐cancer strategies.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals and tumour cell line

Female BALB/c mice, 6 to 8 weeks old, were from Charles River (Iffa‐Credo, L'Arbresle, France). The procedures involving laboratory animals were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines under veterinary supervision. Syngeneic C26 colon carcinoma cells were kindly provided by Mario Colombo (Milan, Italy) and maintained as previously described.10

FKN expression vector constructs

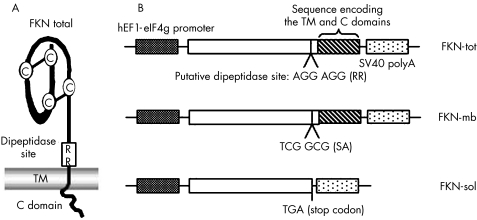

Eukaryotic expression vectors encoding the different forms of murine FKN were constructed in pMG (Invivogen, San Diego, CA, USA) (fig 1A and B). The strictly membrane‐bound variant was generated by mutation of the putative dipeptidase site7,11 using the QuikChange® site‐directed mutagenesis system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). The PCR primers used were 5′‐ACCCAGGCAGCCACATGCGCGCAGGCAGTGGGGCTAC and 5′‐GTAGCCCCACTGCCTGCGCCGATGTGGCTGCCTGGG. The exclusively soluble form of FKN was generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of a truncated cDNA resulting in the deletion of the region encoding the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Figure 1 FKN expression vector constructs. (A) Schematic representation of native FKN and its putative dipeptidase site allowing the proteolytic cleavage to generate the soluble form. (B) Generation of the two molecular variants of FKN. The strictly membrane‐bound form was generated by mutating the putative dipeptidase site. The exclusively soluble variant was obtained by truncation of the cDNA resulting in the deletion of the region encoding the transmembrane (TM) and cytoplasmic (C) domains.

FKN Gene transfer and characterisation of FKN expressing C26 cells

Stable transfection of C26 cells with the empty plasmid (pMG) and the three expression vectors (pFKN‐tot, pFKN‐mb, pFKN‐sol) was performed by using Transfast (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting clones (named C26‐FKN‐tot, C26‐FKN‐sol, C26‐FKN‐mb and C26‐pMG) were selected and maintained in hygromycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The clones were screened for membrane‐bound and soluble FKN expression by flow cytometric analysis and enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Cell proliferation was determined by using the cell proliferation kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Detection of FKN expression by flow cytometry and ELISA

To evaluate the expression of the FKN‐mb on stably‐transfected C26 cells, the cells were washed twice with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with a biotin‐conjugated goat anti‐mouse FKN polyclonal or an isotype‐matched control antibody (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK). After addition of PE‐conjugated streptavidin, cells were analysed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA). To evaluate the shedding of FKN into the culture supernatants of C26 clones, 5×104 cells per well were seeded into a 24‐well plate. Twenty‐four hours later, the cells were re‐fed with fresh medium. Supernatants harvested after 3 hours were assayed by ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems).

In vitro chemotaxis assay

NK cells were purified from spleens with an NK purification kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Paris, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Chemotaxis was assayed in a 24‐well chemotaxis chamber (Becton Dickinson). Supernatants from stably transfected tumour cells conditioned for 48 hours were placed in the lower chamber and spleen‐purified NK cells were seeded on the membrane as previously described.12 After incubation of the 24‐well plate for 4 h at 37°C, 100% humidity and 5% CO2, migrated NK cells were harvested and numerated.

Evaluation of tumourigenic potential

For the induction of subcutaneous and hepatic tumours, 5×104 cells were injected in the right flank or under the liver capsule, respectively. For the induction of pulmonary metastases, 3×104 cells were delivered by intravenous tail injection. For depletion with antibodies, mice were injected intraperitoneal (i.p.), on days −3, 0, +3, +6, +9, and +12 with 20 μg control rabbit antiserum, 20 μg rabbit anti‐asialo‐GM1 serum (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Richmond, VA), 100 μg anti‐CD4 purified Abs (clone GK1.5, PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA), 100 μg anti‐CD8 purified Abs (clone 53–6.7, PharMingen) or 100 μg rat control purified Abs. Cell depletion was assessed by fluorescence‐activated cell‐sorting (FACS) of the CD4+, CD8+ and DX5+ spleen cell compartments.

At predetermined times, complete post‐mortem examinations were performed by a veterinary pathologist. Subcutaneous and hepatic tumours were dissected and measured with callipers in the two perpendicular axes (a and b). Tumour volume was calculated according to the formula ab2π/6.13 The extent of pulmonary tumour development was assessed 15 days post‐injection by recording the number and volume of all tumour nodules visible on the pleural surface under a magnifying glass. Tissue samples were fixed in 10% formalin for routine histology.

FACS analysis of tumour‐infiltrating leukocytes

The tumour mass was surgically removed, minced into small fragments and incubated in collagenase A (2 mg⋅mL−1) and DNAse I (60 μg⋅mL−1) (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) solution for 90 min at 37°C under agitation. The suspension was then filtered through a nylon membrane and centrifuged. Pellets were resuspended in NH4Cl/EDTA/NaHCO3 buffer, and then washed three times with PBS/FCS/EDTA buffer. Phenotypic analysis of infiltrating subpopulations was performed by double‐staining with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐conjugated anti‐CD3e, PE‐conjugated anti‐CD4 (L3T4), anti‐CD8a (Ly‐2) or anti‐CD49 (DX5) (PharMingen,). Analysis was performed on a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were performed using the unpaired Student's t test for means and the non‐parametric Mann–Whitney U test for medians. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Fractalkine expression as soluble and membrane‐bound forms by FKN‐gene‐modified C26 cells

FKN is unique among chemokines because it presents as both a membrane‐anchored form and a secreted form that is derived from the membrane‐bound molecule by proteolytic cleavage. To evaluate the relative contribution of the two forms to the overall antitumour effect of FKN, we have generated murine C26 colon carcinoma cells that constitutively express the native (FKN‐tot), the strictly membrane‐bound (FKN‐mb) or the exclusively soluble (FKN‐sol) form of FKN (fig 1). The strictly membrane‐bound form was generated by mutating the putative dipeptidase site7 whereas the exclusively soluble form was obtained through truncation of the cDNA upstream of the region encoding the TM and C domains (fig 1A and B).

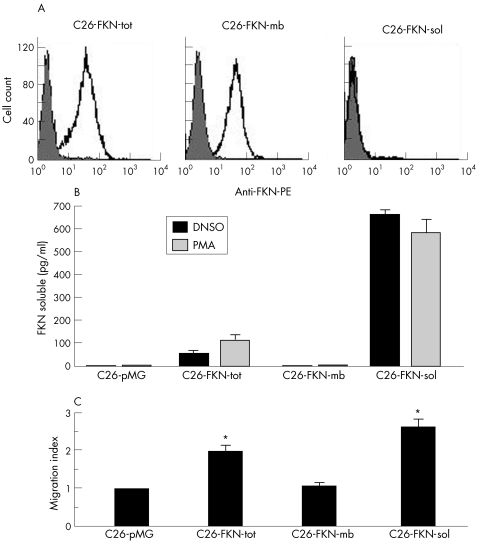

Cell‐surface expression and shedding of FKN by the stably transfected C26 clones were respectively assessed by flow cytometry analysis and ELISA using a specific antibody directed against the extracellular chemokine domain (fig 2A and B). C26‐FKN‐tot clones were selected based on their high levels of expression and shedding (both constitutive and PMA‐inducible) of FKN.14 In contrast, C26‐FKN‐mb cells exclusively expressed the membrane‐bound form of FKN (fig 2A) and did not exhibit any constitutive or inducible cleavage of FKN in vitro (fig 2B). C26‐FKN‐mb clones expressing levels of membrane‐bound FKN similar to those obtained with C26‐FKN‐tot clones were retained for further analysis (fig 2A). As expected, C26‐FKN‐sol clones exclusively produced the soluble form of the chemokine at very high levels (fig 2B).

Figure 2 Characterisation of FKN‐expressing C26 cells. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of stably transfected C26 cells expressing FKN‐tot, FKN‐mb and FKN‐sol. The expression level of the membrane‐bound form of FKN was evaluated by using a specific anti‐mouse FKN polyclonal antibody (open histograms) or goat IgG (filled histograms). Panels are representative of three independent experiments. (B) The shedding of FKN was measured by ELISA in the supernatants from the different C26 clones cultured for 3 hours in the presence or absence of PMA. The results are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) of triplicate determinations. (C) Chemotaxis assay. Spleen‐purified NK cells placed in the upper well of a transwell chamber were assayed for chemotaxis in response to conditioned supernatants from genetically modified C26 cells. The migration index was calculated as the number of cells migrating to the conditioned media divided by the number of cells migrating to the supernatant of the mock‐vector transduced C26‐cells. Results represent the mean and SD of triplicate determinations.

The chemoattractant activity of the three molecular variants of FKN produced by the stably transfected C26 clones was assayed using spleen‐purified murine NK cells (fig 2C). The number of NK cells migrating to the conditioned media of C26‐FKN‐tot and C26‐FKN‐sol was significantly increased compared with control media from C26‐pMG cells (twofold and 2.7‐fold increase, respectively; p<0.05), whereas no migratory response was detected in the supernatant of the C26‐FKN‐mb cells, thus confirming the functionality of the distinct molecular variants of the chemokine. In addition, even though the migratory response was not statistically significant between FKN‐sol and FKN‐tot, there was a marked increase in the mean chemoattracting potential of the FKN‐sol variant compared with the FKN‐tot, which is in total accordance with the secretion patterns of the corresponding clones.

The in vitro growth rate of the three FKN‐producing C26 clones was identical to that of the mock‐transduced C26 cells (C26‐pMG) as determined by a cell proliferation assay (data not shown).

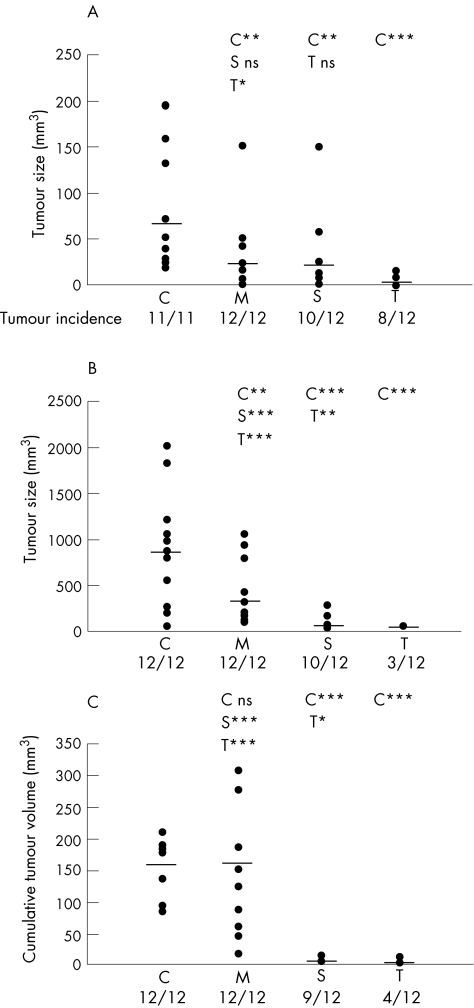

FKN‐sol and FKN‐mb exhibit similar antitumour effects in a subcutaneous model of tumour implantation

We first analysed the extent of tumour development of C26‐FKN‐tot, C26‐FKN‐mb and C26‐FKN‐sol cells compared with the mock transduced C26 cells (C26‐pMG) in the standard model of subcutaneous implantation. Control C26 cells (C26‐pMG) injected in syngeneic BALB/c mice produced a palpable tumour in all the mice, averaging 70.9 mm3 within 12 to 15 days (fig 3A). The constitutive expression of FKN‐tot dramatically reduced overall tumour size (p<0.0001), even though over 80% of the mice had a macroscopically detectable neoplasm at post‐mortem. FKN‐mb and FKN‐sol had similar effects on tumour development (p = 0.505) both being able to reduce the tumour volume to a median size of 25 mm3 (p<0.01). Even though the extent of tumour development was not statistically significant between FKN‐tot and FKN‐sol, there was a considerable difference in median tumour volume (5.1 vs 24.6 mm3) between both groups.

Figure 3 Differential antitumour effect of FKN‐tot, FKN‐sol and FKN‐mb in three models of colon cancer. (A) Subcutaneous tumour model: twelve mice per group were injected with 5×104 C26 cells from each group (C: pMG, M: FKN‐mb, S: FKN‐sol or T: FKN‐tot). Twelve days later, mice were killed and tumour size was measured as described. The median size of tumours and tumour incidence are indicated in each group. (B) Liver tumour model: 5×104 C26 cells were injected under the liver capsule. Two weeks post‐injection, the single hepatic lesions were measured in each group (n = 12). Tumour incidence and median tumour volume are indicated. (C) Pulmonary metastases were generated by intravenous tail injection of 3×104 C26 cells. For each mouse, the number and volume of all tumour nodules visible on the pleural surface after 2 weeks were recorded to estimate the cumulative tumour volume. The graph depicts for all groups the percentage of mice with a given overall tumour volume. Pairwise statistical comparisons are indicated: * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; ns: not significant.

Differential antitumour effect of FKN‐sol and FKN‐mb in a liver model of colon carcinoma

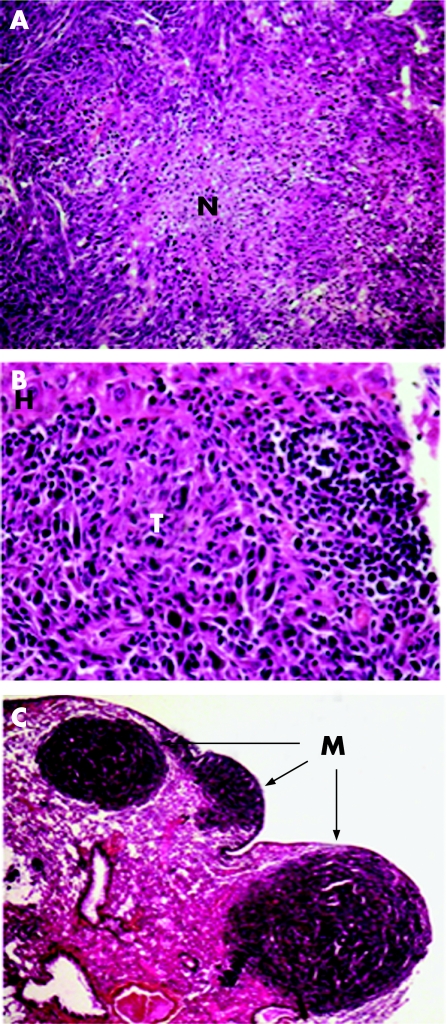

Liver being the main organ targeted by colon carcinoma metastases, we evaluated the ability of FKN‐transfected cells to form solid tumours after injection under the liver capsule. Two weeks after the C26‐pMG cells injection, the mice had developed a single hepatic lesion with a median volume of 900 mm3 (fig 3B). Histologically, C26‐pMG cells produced voluminous tumours composed of cells growing in interlacing bundles or sheets and displaying numerous mitotic figures. Necrotic areas were prominent in the largest tumours (fig 4A) whereas smaller tumours had occasional foci of leukocytic infiltration (fig 4B). FKN‐tot expression by the tumour cells caused a dramatic reduction both in tumour incidence and size (p<0.0001). Only 25% of the mice developed a macroscopically visible tumour that did not exceed 3 mm in diameter (fig 3B). This effect was significantly different from that observed with FKN‐sol (p = 0.002); in this group, over 80% of the animals displayed a tumour with a median volume of 40 mm3. Strikingly, FKN‐mb overexpression had no effect on tumour incidence and only a minor effect on tumour volume compared with the C26‐pMG group. In fact, the difference in tumour size between those two groups was barely significant (p = 0.049). Both C26‐FKN‐tot and C26‐FKN‐sol produced mostly small tumours characteristically infiltrated with mononuclear leukocytes. Strikingly, the smallest lesions featured often necrotic tumour cells admixed with dense infiltrates that comprised predominantly lymphocytes (fig 4B). Interestingly, tumours derived from C26‐FKN‐mb cells displayed a wide spectrum of histological features. Large tumours resembled those induced by C26‐pMG with areas of necrosis and minimal leukocytic infiltration. The most remarkable observations concerned small and medium‐sized lesions, especially the pattern of infiltration of the tumours with inflammatory cells. In fact, these inflammatory infiltrates were almost exclusively restricted to the periphery of the medium‐sized tumours whereas they extended deep into the core of smaller lesions.

Figure 4 Histological analysis of liver tumours and lung metastases. Two weeks post‐injection, complete post‐mortem examinations were performed and tissue samples were fixed in 10% formalin for histology using haematoxylin–eosin staining. Sections from liver (A, B) and lung (C) are shown. (A) Central area of necrosis (N) in a C26‐pMG liver tumour. Original magnification ×10. (B) Extensive leukocytic infiltration in a C26‐FKN‐sol liver tumour (T). H = hepatocytes. Original magnification ×40. (C) Pulmonary metastases (M) produced by C26‐pMG cells. Original magnification ×2.5.

FKN‐mb has no antitumour effect in a metastatic lung model of colon carcinoma

As the lung is second to the liver in overall frequency of metastatic spread in patients with colon cancer, we have developed a pulmonary metastasis model. One hundred per cent of the C26‐pMG injected mice developed haemothorax, and their lungs contained myriad contiguous nodules with an average cumulative volume of 160 mm3 (fig 3C). Histologically, C26‐pMG cells produced mostly sizeable tumours with a prominent perivascular and subpleural tropism (fig 4C); less frequently, smaller clusters of cells were seen in the parenchyma or around small veins. The tumours were highly vascularised with numerous mitotic figures and prominent single cell necrosis. Occasional hemorrhagic foci as well as scattered inflammatory infiltrates were also present.

FKN‐mb had essentially no antitumour effect because 85% of the mice developed haemothorax and all mice had extensive pulmonary pathology. Although there was a reduction in the number of metastatic nodules visible on the pleural surface compared with C26‐pMG, they were often larger, thus resulting in a similar cumulative tumour volume (p = 0.817). By contrast, both FKN‐tot and FKN‐sol had a dramatic effect because none of the mice in those two groups developed haemothorax and the overall tumour load was significantly reduced (p<0.0001). FKN‐tot was again superior to FKN‐sol in tumour incidence (33% vs 75%) and average tumour burden (0.88 mm3 vs 3.76 mm3).

In both C26‐FKN‐tot and C26‐FKN‐sol, small perivascular aggregates were prominent and the tumour cells were often admixed with a population of predominantly mononuclear leukocytes. The tumours produced by C26‐FKN‐mb again displayed a wide spectrum of lesions with all the features seen with C26‐pMG and C26‐FKN‐sol tumours. Nevertheless, voluminous tumours with foci of necrosis, haemorrhage and neutrophilic infiltrates were most common.

Leukocytic contribution in the tumour‐suppressive activity of FKN

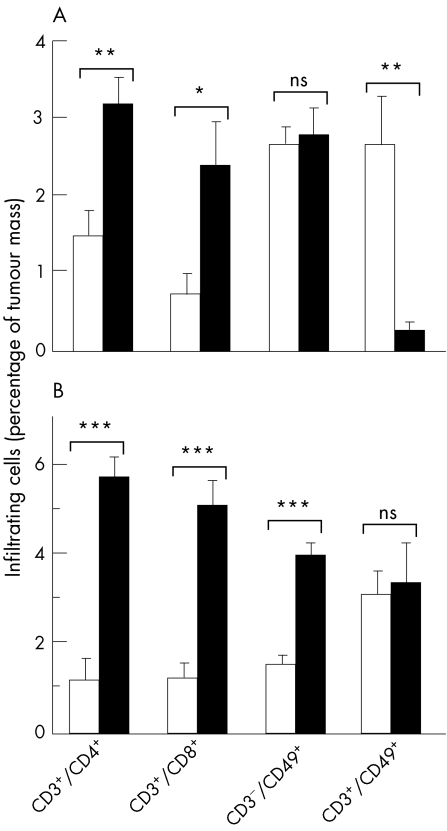

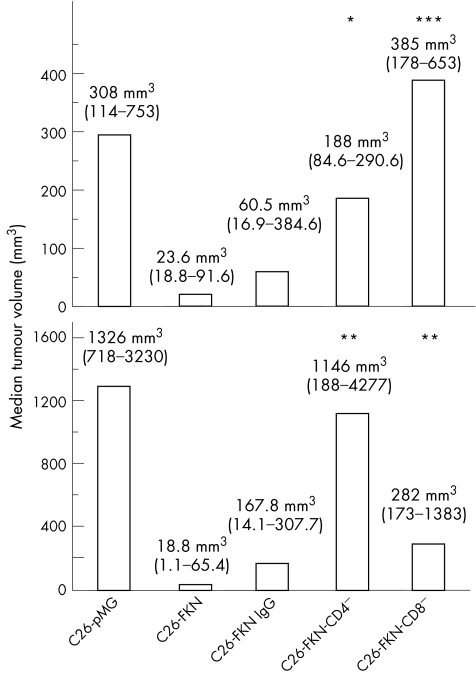

The fact that FKN is described as a chemotactic factor for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, NK and dendritic cells7,15,16,17 prompted us to investigate and to compare the immune mechanisms of the native FKN‐induced antitumour response between the models of subcutaneous and the liver tumours, these experiments being technically hard to achieve in the polymetastatic lung model. Subcutaneous and liver C26‐FKN tumours exhibited greater leukocyte infiltrates than control tumours. FACS analysis of C26‐FKN tumours showed an important accumulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells within both tumour types (fig 5A and B). Moreover, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells were found to play an important role in triggering an immune response in both models because the tumourigenicity of the C26‐FKN cells was markedly increased by specific depleting antibodies (fig 6A and B). However, the relative contribution of these two populations in the antitumour effect of FKN seemed to vary between the skin and the liver tumours, underlying the particular importance of CD8+ cells in the skin and that of CD4+ cells in the liver. Using FACS analysis, we also observed distinct patterns in the number of infiltrating CD3−/CD49+ (presumably NK) and CD3+/CD49+ (presumably NK T) cells according to the tumour implantation site. In both models, however, we failed to detect any role of those cells in the FKN tumour‐suppressive activity using the anti‐asialo‐GM1 depleting treatment (data not shown).

Figure 5 Phenotypic analysis of infiltrating‐leukocytes induced by FKN in subcutaneous and liver tumours. Subcutaneous (A) and hepatic (B) C26‐pMG (open bars) or C26‐FKN (filled bars) tumour masses were removed, digested by DNase and collagenase A and immunostained for two‐colour FACS analysis with FITC‐conjugated anti‐CD3ε, PE‐conjugated anti‐CD4, anti‐CD8α or anti CD49/pan NK antibodies. Results are expressed as the percentage of cells with the indicated phenotype among the total tumour cells in suspension and are expressed as the mean and standard error of at least 12 individual determinations. Some of the individual determinations represent pools of two to four tumours. Student's t test was used for statistical analysis: *** p<0.0001, ns: not significant. Results show a significant accumulation of CD4‐ and CD8‐positive T cells in both the subcutaneous (A) and the liver (B) tumour models but distinct patterns in the number of CD3−/CD49+ (presumably NK) and CD3+/CD49+ (presumably NK T) cells according to the tumour implantation site.

Figure 6 Differential involvement of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in response to fractalkine in the subcutaneous and the liver cancer models. Mice (eight per group) were injected subcutaneously or in the hepatic lobe by C26‐pMG or C26‐FKN cells. The animals received i.p. injections of CD4 depleting (CD4−), CD8 depleting (CD8−) or normal (IgG) antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. Mice were killed 12 days later and the tumour size was evaluated. Both the median tumour volumes and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are indicated. Normal IgG was given as negative control and did not exert any significant effect on skin and liver tumour growth. (B) In the liver, the antitumour effect of FKN was totally abrogated by the CD4‐depleting antibodies and partly impaired by the CD8‐depleting Abs. (A) The identical depleting protocol led to opposite effects in the subcutaneous model. Statistical analyses versus C26‐FKN cells are indicated: * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001.

Discussion

The aims of this study were to investigate the potent antitumour effect of fractalkine, in its three molecular forms, in two distinct orthotopic models of metastatic colon cancer (liver and lung), compared with the standard subcutaneous tumour model. Models of skin tumours are widely used; they constitute a relatively straightforward system for assessing tumourigenicity. However, their physiological relevance is highly questionable because they rarely represent a natural site of implantation for the neoplasm under study. Therefore, conclusions about, for example, tumour growth and dissemination, the antitumoral immune response and any potential implication for cancer patients must be evaluated with great caution.

Our data clearly show that the expression of the native form of fractalkine by C26 tumours drastically reduces their overall metastatic potential and growth in the two physiological target organs. Both the membrane‐bound and the secreted forms of the chemokine contribute to the overall antitumour effect of FKN in the three models of implantation (subcutaneous, liver and lung); however, their respective activity on tumour development varies greatly, depending on the site of metastasis. In the subcutaneous model, FKN‐mb and FKN‐sol have similar effects on tumour incidence and growth, neither of them being able to fully reproduce the effect observed with FKN‐tot. However, the results obtained in the liver and the lungs are in sharp contrast with those observed in the skin; they suggest the poor predictive value of the standard model of subcutaneous implantation. Indeed, the discrepancy between the effects of FKN‐tot and FKN‐sol on the one hand, and FKN‐mb on the other, increases considerably in the liver model compared with the skin and is even more pronounced in the lungs. Whereas FKN‐mb exerts a marked antitumour effect subcutaneously, its effect in the liver is barely significant and, to some extent, seems to promote tumour development in the lungs. In contrast, the soluble form of FKN exerts its tumour‐suppressive activity in all three models. However, it is unable to fully reproduce the overall effect of FKN‐tot and this despite the fact that C26‐FKN‐sol cells secrete considerably higher levels of soluble FKN than C26‐FKN‐tot cells in vitro.

Several hypotheses may explain the discrepancy between the effects of the molecular variants of FKN in the skin, liver and lung. First, we have observed that the immune mechanisms induced by FKN vary widely between target organs for the nature, number and activation state of the immune leukocytes infiltrating the tumour. The antitumour effect of FKN in the skin and the liver was mostly associated with cytotoxic effector CD8 and CD4 lymphocytes. The role of CD8+ T cells in the delayed tumourigenicity strongly suggests a priming of the immune system against the tumour. Several roles have been ascribed to CD4+ T cells such as activation of NK cells through cytokine production, enhancement of macrophage killing activities, dendritic‐cell‐mediated priming of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) as well as direct antitumour activity.18,19 Over the past few years, NK T cells have emerged as an important regulator of immune responses, mainly by their production of immunoregulatory cytokines such as IL‐4, IFN‐γ and TNF, but also by their mediation of cytotoxicity.20 Of interest, several groups have reported the infiltration of NK cells in response to FKN using the standard subcutaneous model to assess the tumourigenicity of lung or colon carcinoma2,3,21 and lymphoma,4 but their precise involvement in the tumour‐suppressive activity of the chemokine has never previously been investigated through depleting experiments or comparable strategies. Several hypothesis may account for the apparent discrepancy between the recruitment and the lack of involvement of NK cells. The lack of contribution can be explained by the escape strategies developed by the tumour cells, which can notably modulate their expression of ligands or adhesive molecules required for the interactions with NK cells.22,23 Furthermore, physicochemical conditions observed in the solid tumours can regulate negatively the activity of NK cells.9 In this regard, our results using both a non‐physiological and an orthotopic model of colon carcinoma show that various mechanisms of the immune response induced by the expression of FKN within C26 tumours are clearly influenced by the tumour implantation site and its immunogenic status, this being a crucial factor in cancer immunotherapy.

In the lung, however, the exact mechanism underlying the antitumour effect of FKN has not been investigated. Our histological analysis suggests that recruitment of leukocytes to the site of tumour implantation may be involved. We are investigating the exact mechanism underlying the relative contribution of the two forms of FKN in two biologically relevant experimental models. It is possible that different stimulation of innate and adaptive immune effectors depending on the tumour microenvironment could account for the differences we observed.

Additionally, it is tempting to speculate that other factors such as the nature and the activity of metalloproteinases, which are responsible for FKN shedding, may vary greatly between the various tumour sites and could significantly influence their antitumour response. At present, relatively little is known about the precise mechanism by which FKN is cleaved from the cell surface, except that this mechanism seems to vary considerably between the numerous cell types studied. Both a constitutive and a PMA‐inducible shedding of FKN have been reported and seem to be mediated by distinct metalloproteinases named ADAM10 (A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase)24 and TACE (ADAM17) respectively.12,25 The di‐arginine sequence in FKN adjacent to the transmembrane domain has been implicated in the constitutive cleavage in some cell types10 but its role is controversial in others.12 The identity of a well‐defined consensus sequence that is responsible for the inducible cleavage has not been reported yet.12 Our data show that FKN expressed by C26 cells is able to undergo both constitutive and inducible cleavage in vitro. In contrast, mutation of the putative dipeptidase site abrogates both shedding mechanisms under normal cell culture conditions. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that other sheddases might cleave FKN, even the mutated form, at a distinct site in vivo. As reported for TACE, metalloproteinase expression varies considerably between organs and can be up‐regulated under many inflammatory conditions, including those found in the tumour microenvironment.26 Therefore, the differential ability of FKN‐mb to prevent tumour growth could simply result from its differential cleavage at the tumour site.

At present, it is difficult to understand how a membrane‐bound protein can exert an antitumour activity. Interestingly, Harrisson et al,11 have reported that stabilisation of the membrane‐bound form of FKN by the elimination of the proteolytic cleavage site induces a greater calcium‐mobilising activity in CX3CR1‐expressing cells present in the environment compared with wild‐type and soluble forms of the chemokine. However, without further experimental evidence, any mechanism involving calcium mobilisation is purely speculative.

Metastatic cells must complete several steps to successfully implant and grow at a distant site. Here, we demonstrate for the first time the antitumour effect of FKN on single liver tumours and lung metastases. Interestingly, we have observed comparable antitumour effects of the chemokine in a polymetastatic liver model in which tumour cells are injected into the portal vein (unpublished data). These results clearly indicate that FKN expression by C26 tumour cells drastically reduces their overall metastatic potential and the growth of tumours in the target organs. Further experiments will be necessary to determine the precise contribution of diverse factors such as the local environment, angiogenesis or the immune system in the antitumour activity of FKN.

Altogether, our findings provide further insights into the immunotherapeutic potential of FKN in metastatic colon cancer and unequivocally underscore the importance of using animal models that closely mimic the physiopathological parameters of the cancer under study to investigate novel anticancer strategies.

Acknowledgements

We thank Arnaud Vanden‐Bossche, Chantal Cros and Jose Barbe for assistance with mouse husbandry, Françoise Senegas‐Balas for discussions, and Marie‐Ange Millet and Isabelle Bourget‐Ponzio for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

FKN - fractalkine

FKN‐tot - total fractalkine

FKN‐mb - membrane‐bound fractalkine

FKN‐sol - soluble fractalkine

Footnotes

Grant support: This work was supported in part by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale and by the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (Grant 3412). BC is the recipient of a post‐doctoral fellowship from the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer.

Competing interest: none declared.

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Gut editions and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence (http://GUT.bmjjournals.com/ifora/licence.pdf.)

References

- 1.Rozen P, Winawer S J, Waye J D. Prospects for the worldwide control of colorectal cancer through screening. Gastrointest Endosc 200255755–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo J, Zhang M, Wang B.et al Fractalkine transgene induces T‐cell‐dependent antitumour immunity through chemoattraction and activation of dendritic cells. Int J Cancer 2003103212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo J, Chen T, Wang B.et al Chemoattraction, adhesion and activation of natural killer cells are involved in the antitumour immune response induced by fractalkine/CX3CL1. Immunol Lett 2003891–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavergne E, Combadiere B, Bonduelle O.et al Fractalkine mediates natural killer‐dependent antitumour responses in vivo. Cancer Res 2003637468–7474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohta M, Tanaka F, Yamaguchi H.et al The high expression of fractalkine results in a better prognosis for colorectal cancer patients. Int J Oncol 20052641–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matloubian M, David A, Engel S.et al A transmembrane CXC chemokine is a ligand for HIV‐coreceptor Bonzo. Nat Immunol 20001298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bazan J F, Bacon K B, Hardiman G.et al A new class of membrane‐bound chemokine with a CX3C motif. Nature 1997385640–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fong A M, Robinson L A, Steeber D A.et al Fractalkine and CX3CR1 mediate a novel mechanism of leukocyte capture, firm adhesion, and activation under physiologic flow. J Exp Med19981881413–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xin H, Kikuchi T, Andarini S.et al Antitumour immune response by CX3CL1 fractalkine gene transfer depends on both NK and T cells. Eur J Immunol 2005351371–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Carlo E, Comes A, Orengo A M.et al IL‐21 induces tumour rejection by specific CTL and IFN‐gamma‐dependent CXC chemokines in syngeneic mice. J Immunol 20041721540–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison J K, Jiang Y, Chen S.et al Role for neuronally derived fractalkine in mediating interactions between neurons and CX3CR1‐expressing microglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 19989510896–10901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavergne E, Combadiere B, Bonduelle O.et al Fractalkine mediates natural killer‐dependent antitumour response in vivo. Cancer Res 2003637468–7474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auerbach R, Morrissey L W, Sidky Y A. Regional differences in the incidence and growth of mouse tumors following intradermal or subcutaneous inoculation. Cancer Res 1978381739–1744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsou C L, Haskell C A, Charo I F. Tumour necrosis factor‐alpha‐converting enzyme mediates the inducible cleavage of fractalkine. J Biol Chem 200127644622–44626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imai T, Hieshima K, Haskell C.et al Identification and molecular characterization of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1, which mediates both leukocyte migration and adhesion. Cell 199791521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papadopoulos E J, Sassetti C, Saeki H.et al Fractalkine, a CX3C chemokine, is expressed by dendritic cells and is up‐regulated upon dendritic cell maturation. Eur J Immunol 1999292551–2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dichmann S, Herouy Y, Purlis D.et al Fractalkine induces chemotaxis and actin polymerization in human dendritic cells. Inflamm Res 200150529–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hung K, Hayashi R, Lafond‐Walker A.et al The central role of CD4(+) T cells in the antitumour immune response. J Exp Med19981882357–2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanzavecchia A. Immunology. Licence to kill. Nature 1998393413–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godfrey D I, MacDonald H R, Kronenberg M.et al NKT cells: what's in a name ? Nat Rev Immunol 20044231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groh V, Wu J, Yee C.et al Tumour‐derived soluble MIC ligands impair expression of NKG2D and T‐cell activation. Nature 2002419734–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maki G, Krystal G, Dougherty G.et al Induction of sensitivity to NK‐mediated cytotoxicity by TNF‐alpha treatment: possible role of ICAM‐3 and CD44. Leukemia 1998121565–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lardner A. The effects of extracellular pH on immune function. J Leukoc Biol 200169522–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hundhausen C, Misztela D, Berkhout T A.et al The disintegrin‐like metalloproteinase ADAM10 is involved in constitutive cleavage of CX3CL1 (fractalkine) and regulates CX3CL1‐mediated cell‐cell adhesion. Blood 20031021186–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garton K J, Gough P J, Blobel C P.et al Tumour necrosis factor‐alpha‐converting enzyme (ADAM17) mediates the cleavage and shedding of fractalkine (CX3CL1). J Biol Chem 200127637993–38001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter S, Clark I M, Kevorkian L.et al The ADAMTS metalloproteinases. Biochem J 200538615–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]