Abstract

Background

Population based studies have revealed varying mortality for patients with ulcerative colitis but most have described patients from limited geographical areas who were diagnosed before 1990.

Aims

To assess overall mortality in a European cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis, 10 years after diagnosis, and to investigate national ulcerative colitis related mortality across Europe.

Methods

Mortality 10 years after diagnosis was recorded in a prospective European‐wide population based cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis diagnosed in 1991–1993 from nine centres in seven European countries. Expected mortality was calculated from the sex, age and country specific mortality in the WHO Mortality Database for 1995–1998. Standardised mortality ratios (SMR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

Results

At follow‐up, 661 of 775 patients were alive with a median follow‐up duration of 123 months (107–144). A total of 73 deaths (median follow‐up time 61 months (1–133)) occurred compared with an expected 67. The overall mortality risk was no higher: SMR 1.09 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.37). Mortality by sex was SMR 0.92 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.26) for males and SMR 1.39 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.93) for females. There was a slightly higher risk in older age groups. For disease specific mortality, a higher SMR was found only for pulmonary disease. Mortality by European region was SMR 1.19 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.53) for the north and SMR 0.82 (95% CI 0.45–1.37) for the south.

Conclusions

Higher mortality was not found in patients with ulcerative colitis 10 years after disease onset. However, a significant rise in SMR for pulmonary disease, and a trend towards an age related rise in SMR, was observed.

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown origin affecting the colon and rectum to a varying extent. The average incidence in Western Europe is estimated to be 10 per 100 0001 but the overall incidence varies considerably throughout the world.2 The disease course may vary from a single attack to chronic disabling symptoms3 that seriously impairs quality of life.4 Whether or not the disease carries a higher mortality risk has not been fully established; some studies have shown lower and others higher mortality than background populations.5,6 In addition, there may be subgroups of patients at risk of death from disease related conditions.7

The aim of this European–Israeli population based multicentre study was to compare mortality in patients with ulcerative colitis with mortality in the background population, and to examine disease specific causes of death in the various subgroups.

Patients and methods

Patients and centres

The present investigation was part of a follow‐up study conducted by the European Collaborative Study Group of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC‐IBD). In the EC‐IBD study, a population based prospective diagnosed inception cohort of 2201 patients with inflammatory bowel disease were recruited from 20 treatment centres in different geographical areas in 12 European countries over a 2 year period between 1 October 1991 and 30 September 1993.8 Patients were classified according to the diagnostic criteria of Lennard‐Jones and Truelove and Witts,9 and 1379 patients were classified with ulcerative colitis, the rest having either Crohn's disease or indeterminate colitis.10

After 10 years, each of the 20 centres was invited to participate in the follow‐up study reported here. Thirteen, with 1022 (74%) of the original 1379 patients with ulcerative colitis, agreed, and seven did not participate for technical or logistical reasons, such as difficulties in establishing administrative routines, and lack of qualified study personnel and hospital facilities necessary to carry out the follow‐up. This did not alter the population based character of the study because every centre had met the criteria for population based patient inclusion at the formation of the cohort. Before data collection, a patient response rate per centre was set to a minimum of 60% to ensure the population based nature of the cohort. Patients were followed‐up from the inception period (1 October 1991 to 30 September 1993) to the data inclusion period of the present study, between 1 August 2002 and 31 January 2004, or to a time prior to this period if the patient had died or been lost to follow‐up.

This 10 year follow‐up study was supported financially by the European Union. Further details of the planning, financing and methods used have been described in previous publications from the EC‐IBD.10,11

Methods

The centres in Greece, Israel, Italy and Spain are referred to as southern centres and those in Denmark (the Copenhagen centre), the Netherlands and Norway as northern centres.

The patient's vital status was assessed from hospital charts and contact with relatives and general practitioners by mail or telephone. In the Scandinavian countries, additional information was obtained from the national death certificate registries. Dates and causes of death were registered using single level clinical classical software (CCS)12 based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10).13 In the CCS, ICD‐10 codes are broken down into a smaller number of clinically meaningful categories, thus creating broad diagnostic groups which are more useful for descriptive statistics than individual ICD‐10 codes. The CCS aggregates illnesses and conditions into 259 mutually exclusive categories, most of which are homogeneous.

Expected mortality was calculated from the WHO Mortality Database for the years 1995‐1998 using ICD‐9 (for the centres in Greece, Italy and Spain) and ICD‐10 (for the centres in Denmark, Israel, Norway and The Netherlands).14 The relation between ulcerative colitis and the cause of death was evaluated separately for each individual case on the basis of the collected data. Disease extent was calculated from findings at endoscopy, if necessary supplemented by radiology and findings at surgery. Disease extent proximal to the splenic flexure was classified as extensive colitis, colonic inflammation distal to the splenic flexure as distal colitis and disease limited to the rectum 15 cm above the linea dentata as proctitis. Disease extent at diagnosis was based on results from endoscopy, and in a limited number of cases supplemented by radiology or findings at surgery.

Information on drug use was obtained from the medical records updated at each follow‐up visit. A patient registered as having used a drug during one or more time periods during follow‐up was classified as a drug user, and for these patients the proportion of time of follow‐up in which the medication was given was calculated. The most common systemically used drugs were chosen for analysis. These were grouped into aminosalicylates (5‐ASA), including sulfasalazine, glucocorticosteroids (GCS), and azathioprine and 6‐mercaptopurine (AZA/6MP). The use of other drugs such as methotrexate and ciclosporin was considered to be negligible because of the small number of patients who used them, and was therefore not included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Standardised mortality ratio (SMR) was calculated by dividing observed mortality by expected mortality using country, age and sex specific data from the WHO Mortality Database (31 January 2004 update). Byar's approximation was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).15 The χ2 test, t test and the Mann–Whitney U test were performed to identify possible differences in sex, age, geographical location and disease extent between patients followed up for the whole period and those lost to follow‐up, and to compare subgroups of patients during follow–up regarding time of survival, smoking and medical treatment. Observed survival was calculated using the Kaplan—Meyer technique. Expected survival curves were calculated using age specific mortality and age and sex specific distribution of person‐years of the cohort. Cox regression analysis was used to identify risk factors for mortality using the proportional hazards assumption.

Results

Follow‐up

Nine of the 13 centres met the threshold limit of 60% response, giving a total of 781 patients from these centres for follow‐up. There were no significant differences in the distribution of sex or age at diagnosis or north–south location between these nine centres and the 11 non‐participating centres of the original cohort. Of the 781 patients, 661 were known to be alive when the follow‐up data collection was started in August 2004, and 73 patients had died during the follow‐up period. The vital status at study end point was unknown in 47 patients who were lost to follow‐up, 41 of whom were followed during varying time intervals (median follow‐up time 35 months (range 1–91)). Six of these patients appeared to have a date of the most recent visit that was the same as the date of diagnosis. Thus a total of 775 patients were available for follow‐up analyses (404 males and 371 females with a mean age of 37 years at diagnosis (range 16–88)). Patients with unknown vital status were no different from the rest of the cohort in terms of sex, age or proportion with extensive colitis at diagnosis.

Overall mortality

Table 1 shows the total mortality, and mortality according to age, sex, residence and disease extent at diagnosis

Table 1 Male, female and cohort specific mortality according to age (sex and country adjusted), disease extent at diagnosis (age, sex and country adjusted) and residence (age and sex adjusted).

| Age (y) | Males | Females | Entire cohort | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Dead | Exp | SMR (95%CI) | n | Dead | Exp | SMR (95%CI) | n | Dead | Exp | SMR (95%CI) | |

| Age at diagnosis (y) | ||||||||||||

| 10–19 | 15 | 0 | 0.12 | 0 (–) | 25 | 0 | 0.08 | 0 (–) | 40 | 0 | 0.19 | 0 (–) |

| 20–29 | 84 | 0 | 0.92 | 0 (–) | 108 | 1 | 0.53 | 1.89 (0.02–10.53) | 192 | 1 | 1.45 | 0.69 (0.01–3.84) |

| 30–39 | 89 | 1 | 1.68 | 0.60 (0.01–3.31) | 85 | 0 | 0.92 | 0 (–) | 174 | 1 | 2.60 | 0.38 (0.01–2.14) |

| 40–49 | 86 | 1 | 4.10 | 0.24 (0.00–1.36) | 41 | 1 | 0.98 | 1.02 (0.01–5.65) | 127 | 2 | 5.08 | 0.39 (0.04–1.42) |

| 50–59 | 55 | 6 | 6.41 | 0.94 (0.34–2.04) | 43 | 6 | 2.60 | 2.30 (0.84–5.02) | 98 | 12 | 9.02 | 1.33 (0.69–2.33) |

| 60–69 | 46 | 12 | 13.76 | 0.87 (0.45–1.52) | 35 | 5 | 5.27 | 0.95 (0.31–2.22) | 81 | 17 | 19.03 | 0.89 (0.52–1.43) |

| 70–79 | 25 | 16 | 11.81 | 1.36 (0.77–2.20) | 27 | 15 | 12.46 | 1.20 (0.67–1.99) | 52 | 31 | 24.27 | 1.28 (0.87–1.81) |

| 80–89 | 4 | 2 | 2.73 | 0.73 (0.08–2.65) | 7 | 7 | 2.42 | 2.90 (1.16–5.97) | 11 | 9 | 5.15 | 1.75 (0.80–3.32) |

| Disease extent at diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Proctitis | 91 | 8 | 6.53 | 1.22 (0.53–2.41) | 134 | 10 | 7.70 | 1.30 (0.62–2.39) | 225 | 18 | 14.23 | 1.27 (0.75–2.00) |

| Distal colitis | 204 | 21 | 25.09 | 0.84 (0.52–1.28) | 130 | 11 | 10.04 | 1.10 (0.55–1.96) | 334 | 32 | 35.13 | 0.91 (0.62–1.29) |

| Extensive colitis | 96 | 9 | 8.20 | 1.10 (0.50–2.08) | 94 | 12 | 6.66 | 1.80 (0.93–3.15) | 190 | 21 | 14.86 | 1.41 (0.87–2.16) |

| Country | ||||||||||||

| Greece | 53 | 2 | 5.25 | 0.38 (0.04–1.38) | 37 | 1 | 1.11 | 0.90 (0.01–5.00) | 90 | 3 | 6.36 | 0.47 (0.09–1.38) |

| Israel | 24 | 0 | 1.17 | 0 (–) | 15 | 2 | 0.49 | 4.06 (0.46–14.66) | 39 | 7 | 5.39 | 1.30 (0.52–2.68) |

| Italy | 50 | 4 | 3.95 | 1.01 (0.27–2.59) | 36 | 3 | 1.44 | 2.08 (0.42–6.07) | 86 | 2 | 1.66 | 1.20 (0.14–4.35) |

| Spain | 30 | 2 | 2.78 | 0.72 (0.08–2.59) | 33 | 0 | 0.97 | 0 (–) | 63 | 2 | 3.75 | 0.53 (0.06–1.93) |

| Denmark | 38 | 6 | 4.04 | 1.49 (0.54–3.24) | 50 | 9 | 5.88 | 1.53 (0.70–2.91) | 88 | 15 | 9.91 | 1.51 (0.85–2.50) |

| Norway | 129 | 21 | 15.59 | 1.35 (0.83–2.06) | 140 | 16 | 12.66 | 1.26 (0.72–2.05) | 269 | 37 | 28.25 | 1.31 (0.92–1.81) |

| The Netherlands | 80 | 3 | 8.75 | 0.34 (0.07–1.00) | 60 | 4 | 2.70 | 1.48 (0.40–3.79) | 140 | 7 | 11.45 | 0.61 (0.24–1.26) |

| Southern centres | 157 | 8 | 13.14 | 0.61 (0.26–1.20) | 121 | 6 | 4.02 | 1.49 (0.55–3.25) | 278 | 14 | 17.16 | 0.82 (0.45–1.37) |

| Northern centres | 247 | 30 | 28.38 | 1.06 (0.71–1.51) | 250 | 29 | 21.24 | 1.37 (0.91–1.96) | 497 | 59 | 49.61 | 1.19 (0.91–1.53) |

| All patients | 404 | 38 | 41.52 | 0.92 (0.65–1.26) | 371 | 35 | 25.26 | 1,39 (0,97–1,93) | 775 | 73 | 66.78 | 1.09 (0.86–1.37) |

n, Number of patients; Exp, expected number of deaths; SMR, standardised mortality ratio.

Southern centres, centres in Greece, Israel, Italy and Spain.

Northern centres, centres in Denmark (Copenhagen), The Netherlands and Norway;

Twenty six patients without known disease extent were excluded from the analysis of disease extent and mortality.

Only patients over age 15 years were entered into the cohort.

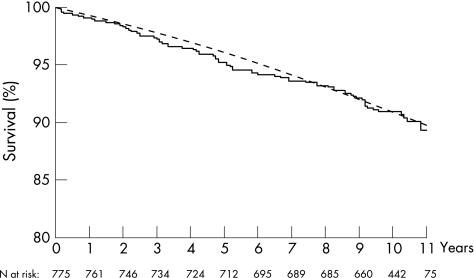

At the end of follow‐up, 661patients were known to be alive (median follow‐up time 123 months (range 107–144)). Seventy three patients had died (median time from diagnosis until death 61 months (range 1–133)), and 66.8 were expected to die (SMR 1.09 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.37)). When the observed survival curve was compared with the expected curve based on aggregated mortality statistics of all participating countries, as shown in fig 1, there was no significant increase in overall mortality risk. Observed mortality was almost identical to the expected numbers after 1 year, 5 years and 10 years of follow‐up. No significantly higher mortality risk was found for females (SMR 1.39 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.93)), males (0.92 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.26)), northern (1.19 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.53)) or southern (0.82 (95% CI 0.45–1.37)) European centres even though there was a trend towards higher mortality for females and for northern centres.

Figure 1 Total observed survival of the entire cohort (—) compared with expected survival (‐‐‐) based on aggregated mortality statistics of all participating countries. Overall observed versus expected survival was 99.1% versus 99.3%, 95.9% versus 95.3% and 90.9% versus 90.9% 1 year, 5 years and 10 years after diagnosis, respectively. Note the limited scale range on the vertical axis. n, number of patients.

Phenotype at diagnosis and associated mortality

Mortality according to age and disease extent at diagnosis, sex and country is presented in table 1 The number of cases of proctitis was 30% for the whole cohort, with a male/female ratio of 0.6. There were no statistically significant differences in SMR according to disease extent at diagnosis. Table 1 shows that SMR tended to increase with age at diagnosis but age at diagnosis was only statistically significant in females of 80 years and over. The overall SMR for females showed only a non‐significant increase.

Use of drugs and mortality

Data on drug treatment according to vital status at the end of follow‐up are presented in table 2.

Table 2 Use of systemic drugs from time of inclusion to colectomy, death, lost to follow‐up or study completion.

| 5‐ASA | GCS | AZA/6MP | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| User n | Time of use | Non‐ user n | No data n | User n | Time of use | Non‐ user n | No data n | User n | Time of use | Non‐ user n | No data n | |

| Vital status at the end of the study | ||||||||||||

| Dead | 55 | 1.0 | 15 | 3 | 32 | 0.3 | 38 | 3 | 3 | 0.1 | 67 | 3 |

| Alive | 553 | 0.8 | 90 | 18 | 287 | 0.1 | 356 | 18 | 51 | 0.2 | 589 | 21 |

| Unknown | 31 | 0.9 | 9 | 1 | 10 | 0.1 | 30 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 39 | 1 |

| Total | 639 | 0.9 | 114 | 22 | 329 | 0.1 | 424 | 22 | 55 | 0.2 | 695 | 25 |

5‐ASA, sulfasalazine/5‐aminosalicylicacid; GCS, glucocorticosteroids; AZA/6MP, azathioprin/6‐mercaptopurine; No data, no available information on drug use; Non‐user, drug not used in follow‐up; User, drug used in follow‐up; Time of use, proportion of time on medication during follow‐up, median value calculated for drug users only.

With regards to the number of patients on medication, there were no significant differences between the dead and survivors for any of the three groups of drugs. However, duration of treatment was higher in the mortality group than in patients who survived throughout the follow‐up period, both for 5‐ASA (p = 0.04) and for GCS (p = 0.01), but not for AZA/6MP (p = 0.7).

Disease specific mortality

Table 3 shows disease specific mortality for the whole cohort.

Table 3 Disease specific mortality for the main diagnostic groups (age, sex and country adjusted) and disease location at diagnosis (age, sex and country adjusted).

| n | Cancer causes CCS ICD‐10: 011‐044 | Cardiovascular causes CCS ICD‐10: 099–118 | Pulmonary causes CCS ICDD‐10: 122–134 | Gastrointestinal causes CCS ICD‐10: 138–155 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead | Exp | SMR (95%CI) | Dead | Exp | SMR (95%CI) | Dead | Exp | SMR (95%CI) | Dead | Exp | SMR (95%CI) | ||

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Male | 404 | 12 | 12.31 | 0.97 (0.50–1.70) | 16 | 16.15 | 0.99 (0.57–1.61) | 6 | 3.27 | 1.83 (0.67–3.99) | 2 | 1.52 | 1.31 (0.15–4.75) |

| Female | 371 | 7 | 6.63 | 1.06 (0.42–2.18) | 12 | 10.05 | 1.19 (0.62–2.09) | 5 | 2.19 | 2.28 (0.74–5.32) | 3 | 0.94 | 3.18 (0.64–9.29) |

| Disease extent at diagnosis | |||||||||||||

| Proctitis | 225 | 5 | 4.19 | 1.19 (0.38–2.79) | 7 | 5.16 | 1.36 (0.54–2.80) | 3 | 1.13 | 2.65 (0.53–7.73) | 0 | 0.58 | 0 (–) |

| Distal colitis | 334 | 9 | 9.81 | 0.92 (0.42–1.74) | 12 | 14.13 | 0.85 (0.44–1.48) | 3 | 3.04 | 0.99 (0.20–2.88) | 3 | 1.26 | 2.39 (0.48–6.97) |

| Extensive colitis | 190 | 5 | 4.19 | 1.19 (0.38–2.79) | 7 | 5.88 | 1.19 (0.48–2.45) | 5 | 1.13 | 4.44 (1.43–10.35) | 2 | 0.53 | 3.74 (0.42–13.51) |

| Country | |||||||||||||

| Greece | 90 | 2 | 1.89 | 1.06 (0.12–3.83) | 1 | 2.74 | 0.37 (0–2.03) | 0 | 0.33 | 0 (–) | 0 | 0.18 | 0 (–) |

| Italy | 86 | 0 | 1.82 | 0 (–) | 6 | 1.83 | 3.29 (1.20–7.15) | 0 | 0.25 | 0 (–) | 1 | 0.31 | 3.26 (0.04–18.15) |

| Israel | 39 | 1 | 0.45 | 2.24 (0.03–12.46) | 0 | 0.52 | 0 (–) | 1 | 0.07 | 13.37 (0.17–71.41) | 0 | 0.05 | 0 (–) |

| Spain | 63 | 2 | 1.22 | 1.64 (0.18–5.91) | 0 | 1.11 | 0 (–) | 0 | 0.31 | 0 (–) | 0 | 0.23 | 0 (–) |

| Denmark | 88 | 3 | 2.85 | 1.05 (1.21–3.08) | 3 | 3.56 | 0.84 (0.17–2.46) | 7 | 0.90 | 7.79 (3.12–16.04) | 1 | 0.46 | 2.17 (0.03–12.09) |

| Norway | 269 | 11 | 6.88 | 1.60 (0.80–2.86) | 13 | 12.31 | 1.06 (0.56–1.81) | 3 | 2.62 | 1.15 (0.23–3.35) | 1 | 0.85 | 1.18 (0.02–6.55) |

| The Netherlands | 140 | 0 | 3.84 | 0 (–) | 5 | 4.14 | 1.21 (0.39–2.82) | 0 | 0.98 | 0 (–) | 2 | 0.38 | 5.28 (0.59–19.08) |

| Southern centres | 278 | 5 | 5.38 | 0.93 (0.30–2.17) | 7 | 6.19 | 1.13 (0.45–2.33) | 1 | 0.96 | 1.04 (0.01–5.77) | 1 | 0.78 | 1.29 (0.02–7.16) |

| Northern centres | 497 | 14 | 13.56 | 1.03 (0.56–1.73) | 21 | 20.01 | 1.05 (0.65–1.60) | 10 | 4.50 | 2.22 (1.06–4.09) | 4 | 1.69 | 2.37 (0.64–6.07) |

| All patients | 775 | 19 | 18.94 | 1.00 (0.60–1.57) | 28 | 26.20 | 1.07 (0.71–1.54) | 11 | 5.46 | 2.01 (1.00–3.60) | 5 | 2.47 | 2.03 (0.65–4.73) |

n, Number of patients; Exp, expected number of deaths; SMR, standardised mortality ratio; CCS, clinical classifications software; ICD, International Classification of Disease.

Twenty six patients without known disease extent were excluded from the analysis of disease extent and mortality.

The cause of death was poorly defined in two patients. Of the four main diagnostic groups, a significantly higher mortality was found for pulmonary disease (SMR 2.01 (95% CI 1.00 to 3.60). Of the 11 patients who died from pulmonary disease, seven were in the Copenhagen cohort (Denmark), giving an SMR of 7.79 (95% CI 3.12 to 16.04). There was no increase in SMR for malignant disease. Only one death related to colorectal cancer (CRC) was observed, and the patient died of surgical complications. In two other cases, CRC was diagnosed in the last five months before death but was not considered to be the cause of death. No rise in mortality from non‐malignant gastrointestinal disease was observed.

Mortality and relation to ulcerative colitis

Table 4 shows details of the five patients in whom the cause of death was considered to be possibly or probably related to ulcerative colitis. Table 5 shows the patients with causes of death unlikely to be related to ulcerative colitis.

Table 4 Cause of death possibly or probably related to ulcerative colitis.

| Patient and UC related death | Centre | Sex | Disease extent at diagnosis | Age at diagnosis (y) | Survival after diagnosis (months) | Surgery related | Cause of death | CCS ICD‐10 code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal causes | ||||||||

| 1 Probable | Oslo | M | Distal | 79 | 29 | Yes | Acute myocardial infarction at partial colectomy for CRC | 144 |

| 2 Probable | South Limburg | F | extensive | 59 | 37 | Yes | Cardiac complications at total colectomy for resistant UC | 144 |

| 3 Probable | Copenhagen | F | Extensive | 87 | 3 | Yes | Active UC. Subtotal colectomy, abscess found | 148 |

| 4 Probable | South Limburg | F | Distal | 71 | 99 | Yes | Peritonitis and septicaemia. Acute subtotal colectomy, findings of abscess and perforation. | 148 |

| Cardiovascular causes | ||||||||

| 5 Possible | Cremona | M | Extensive | 63 | 14 | No | Acute cerebrovascular disease. Disease activity within the last 2 months of death, use of topical and systemic GCS and ciclosporin | 109 |

CCS, clinical classifications software; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Table 5 Causes of death not likely to be related to ulcerative colitis.

| Patient No | Centre | Sex | Disease extent at diagnosis | Age at diagnosis (y) | Survival after diagnosis (months) | Cause of death | CCS ICD‐10 code | Circumstances at death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | ||||||||

| 1 | Copenhagen | F | Extensive | 77 | 58 | Cancer of head and neck | 11 | Long term use of systemic GCS followed by azathioprine |

| 2 | Copenhagen | M | Proctitis | 52 | 50 | Cancer of stomach | 13 | No immunosuppressives |

| 3 | Heraklion | F | Proctitis | 62 | 63 | Cancer of stomach | 13 | No immunosuppressives |

| 4 | Oslo | M | Distal | 74 | 72 | Cancer of stomach | 13 | No immunosuppressives |

| 5 | Oslo | M | Extensive | 65 | 1 | Cancer of the liver | 16 | No immunosuppressives |

| 6 | Oslo | M | Proctitis | 87 | 26 | Cancer pancreatitis | 17 | Systemic GCS used |

| 7 | Beer Sheeva | F | Extensive | 54 | 58 | Cancer of the gall blather | 18 | No immunosuppressive. No sign of UC related liver disease |

| 8 | Heraklion | M | Proctitis | 56 | 133 | Bronchus carcinoma | 19 | No immunosuppressives |

| 9 | Vigo | M | Distal | 59 | 45 | Bronchus carcinoma | 19 | No immunosuppressives |

| 10 | Oslo | F | Extensive | 53 | 110 | Breast cancer | 24 | No immunosuppressives |

| 11 | Oslo | F | Extensive | 83 | 23 | Breast cancer | 24 | No immunosuppressives |

| 12 | Oslo | F | Proctitis | 61 | 40 | Cancer of uterus | 25 | No immunosuppressives |

| 13 | Vigo | M | Distal | 72 | 51 | Cancer of prostate | 29 | Long term use of systemic GCS |

| 14 | Oslo | M | Distal | 61 | 105 | Cancer of brain and nervous system | 35 | No immunosuppressives |

| 15 | Oslo | M | Distal | 59 | 106 | Non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma | 38 | No immunosuppressives |

| 16 | Oslo | M | Distal | 67 | 8 | Leukaemia | 39 | No immunosuppressives |

| 17 | Oslo | M | Distal | 74 | 83 | Cancer of the prostate | 29 | No immunosuppressives |

| 18 | Oslo | F | Distal | 79 | 124 | Myelofibrosis. | 39 | No UC activity. CRC surgery 5 months before death. |

| 19 | Copenhagen | M | Distal | 73 | 93 | Multiple myeloma | 40 | No immunosuppressives |

| Cardiovascular causes | ||||||||

| 20 | Reggio Emilia | F | Unknown | 63 | 70 | Acute cerebral haemorrrhagia | 85 | No immunosuppressives |

| 21 | Oslo | M | Proctitis | 49 | 132 | Acute myocardial infarction | 100 | No UC activity. Topical GCS |

| 22 | Oslo | M | Distal | 67 | 38 | Acute myocardial infarction | 100 | No UC activity |

| 23 | Oslo | M | Extensive | 68 | 89 | Acute myocardial infarction | 100 | No UC activity |

| 24 | Reggio Emilia | M | Extensive | 73 | 21 | Acute myocardial infarction | 100 | No UC activity |

| 25 | South Limburg | M | Distal | 63 | 125 | Acute myocardial infarction | 100 | No UC activity |

| 26 | South Limburg | F | Distal | 67 | 10 | Acute myocardial infarction | 100 | Systemic GCS |

| 27 | South Limburg | M | Extensive | 69 | 113 | Acute myocardial infarction | 100 | No UC activity |

| 28 | Oslo | M | Distal | 69 | 107 | Coronary atherosclerosis | 101 | No UC activity |

| 29 | Copenhagen | F | Proctitis | 77 | 115 | Other and ill defined heart disease | 104 | No UC activity |

| 30 | Cremona | F | Proctitis | 85 | 18 | Congestive heart failure | 108 | No UC activity |

| 31 | Oslo | M | Extensive | 67 | 80 | Congestive heart failure | 108 | No UC activity |

| 32 | Oslo | F | Distal | 70 | 110 | Congestive heart failure | 108 | No UC activity |

| 33 | Oslo | F | Distal | 73 | 13 | Congestive heart failure | 108 | No UC activity |

| 34 | Oslo | F | Extensive | 80 | 110 | Congestive heart failure | 108 | No UC activity |

| 35 | Oslo | M | Distal | 88 | 56 | Congestive heart failure | 108 | No immunosuppressives |

| 36 | Reggio Emilia | M | Distal | 71 | 130 | Congestive heart failure | 108 | No UC activity |

| 37 | Copenhagen | F | Distal | 58 | 51 | Acute cerebrovascular disease | 109 | No UC activity |

| 38 | Cremona | F | Distal | 75 | 40 | Acute cerebrovascular disease | 109 | No UC activity |

| 39 | Oslo | M | Extensive | 77 | 27 | Acute cerebrovascular disease | 109 | No UC activity |

| 40 | Oslo | M | Proctitis | 80 | 49 | Acute cerebrovascular disease | 109 | No UC activity |

| 41 | South Limburg | M | Proctitis | 33 | 99 | Acute cerebrovascular disease | 109 | No UC activity |

| 42 | South Limburg | F | Distal | 54 | 103 | Acute cerebrovascular disease | 109 | No UC activity |

| 43 | Oslo | M | Proctitis | 58 | 37 | Peripheral atherosclerosis | 114 | No UC activity |

| 44 | Copenhagen | F | Unknown | 77 | 35 | Arteriosclerosis | 115 | No immunosuppressives |

| 45 | Ioannina | M | Distal | 72 | 25 | Phlebitis, thrombophlebitis and thrombosis | 118 | No UC activity |

| 46 | Oslo | F | Proctitis | 80 | 6 | Phlebitis, thrombophlebitis and thrombosis | 118 | No UC activity |

| Pulmonary causes | ||||||||

| 47 | Beer Sheeva | F | Extensive | 58 | 103 | Pneumonia | 122 | Possible steroid use |

| 48 | Copenhagen | M | Extensive | 66 | 24 | Pneumonia | 122 | No immunosuppressives |

| 49 | Copenhagen | F | Extensive | 67 | 61 | Pneumonia | 122 | No immunosuppressives |

| 50 | Copenhagen | M | Proctitis | 67 | 61 | Pneumonia | 122 | No immunosuppressives |

| 51 | Copenhagen | M | Distal | 70 | 36 | COPD | 127 | No UC activity |

| 52 | Copenhagen | F | Proctitis | 70 | 70 | COPD | 127 | No UC activity |

| 53 | Copenhagen | M | Extensive | 74 | 93 | Pneumonia | 122 | No immunosuppressives |

| 54 | Copenhagen | F | Extensive | 77 | 109 | Pneumonia | 122 | No immunosuppressives |

| 55 | Oslo | F | Proctitis | 56 | 83 | COPD | 127 | No UC activity |

| 56 | Oslo | M | Distal | 70 | 57 | Pneumonia | 122 | No immunosuppressives |

| 57 | Oslo | M | Distal | 70 | 57 | Pneumonia | 122 | No immunosuppressives |

| Gastrointestinal causes | ||||||||

| 58 | Cremona | male | distal | 58 | 2 | Gastrointestinal haemorrhage | 153 | Bleeding oesophageal varices in cirrhosis from hepatitis B |

| Other causes | ||||||||

| 59 | Oslo | F | Distal | 76 | 111 | Septicaemia | 2 | No immunosuppressives |

| 60 | Oslo | M | Distal | 71 | 97 | Diabetes melliltus with complications | 50 | No UC activity |

| 61 | Copenhagen | F | Proctitis | 77 | 63 | Fluid and electrolyte disorder | 55 | No UC activity |

| 62 | Oslo | F | Distal | 82 | 78 | Organic mental disorder | 68 | No UC activity |

| 63 | Oslo | F | Extensive | 79 | 30 | Hip fracture | 226 | Use of systemic GCS |

| 64 | Oslo | F | Distal | 28 | 62 | Residual code, unclassified | 259 | No UC activity |

| 65 | Oslo | M | Distal | 74 | 110 | Residual code, unclassified | 259 | No UC activity |

| 66 | Oslo | F | Proctitis | 74 | 123 | Residual code, unclassified | 259 | Use of systemic GCS |

| 67 | Oslo | F | Extensive | 82 | 2 | Residual code, unclassified | 259 | No immunosuppressives |

| 68 | Oslo | F | Proctitis | 88 | 30 | Residual code, unclassified | 259 | No immunosuppressives |

GCS, glucocorticosteroids; CCS, clinical classifications software; ICD, International Classification of Disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Mean age at diagnosis was 71.8 years in the ulcerative colitis related group and 68.5 in the non‐ulcerative colitis related mortality group (95% CI to 13.7–7.3). Median survival time was 29 months for ulcerative colitis related compared with 61.5 months in non‐ulcerative colitis related deaths (p = 0.09). Four patients died in association with surgery, two of intra‐abdominal infections and two of acute cardiac complications. One death, from acute cerebrovascular disease, was considered to be possibly caused by adverse effects of medical treatment for ulcerative colitis. The Cox regression model for total mortality was dominated by the age specific effects on total mortality and therefore did not yield any independent risk factor for ulcerative colitis related mortality.

Discussion

The overall mortality in this European population based multicentre cohort was no higher than that of the background population. None of the factors that were analysed for a possible impact on mortality were statistically significant. Older age groups at diagnosis and female sex only showed a trend towards higher mortality.

Previous studies from different geographical regions are not in complete agreement as to whether ulcerative colitis is a risk factor for mortality5,16,17,18,19 or not.6,7,20,21,22 Many of these studies were hospital based, retrospective or covered periods of many years. Thus their results must be interpreted with caution as they used different criteria for selection of patients, and as both treatment and disease behaviour change over time.23 The present study had a short inclusion period of 2 years, patients were selected from a range of centres across Europe and Israel, the geographical areas were well defined and it was population based and employed uniform diagnostic criteria. All of the patients were followed‐up for the same time period so that those who completed follow‐up had comparable observation times.

A higher mortality risk in ulcerative colitis has mostly been reported in older studies16,17,18 while more recent ones have shown a mortality rate comparable to that of the background population, which is in accordance with the findings in our study.6,21 This may be due to a more favourable disease pattern or to improvements in treatment in recent decades although long term follow‐up studies from Denmark and the UK have failed to show any change in mortality over time.7,21 Excess mortality during the first year of ulcerative colitis has been reported,21 a finding that is not supported by our study. The values for survival in our cohort were almost identical to those expected throughout the entire 10 years. Our study also failed to show any rise in SMR for non‐malignant gastrointestinal disease, as has been reported in earlier studies.5,17,18 A large study from Copenhagen showed excess mortality related to ulcerative colitis as a result of postoperative complications.7 Our data did not support the finding of higher mortality related to colectomy in ulcerative colitis, despite the occurrence of four surgery related deaths.

Our findings are in line with the study of Farrokhyar et al that showed no relation between death and ulcerative colitis.21 Only one death from CRC was found in our study. A 10 year follow‐up period is, however, too short to conclude whether or not CRC has an impact on ulcerative colitis related mortality because this cancer is known to have a long latency period. Patients with an ulcerative colitis related cause of death tended to have a shorter life expectancy from the time of diagnosis than patients who died from other diseases. This could have been due to the surgery related mortality which occurred in four of the five patients who died of ulcerative colitis related causes.

Older age at diagnosis has been shown to be a mortality risk factor by Winther and colleagues7 and Farrokhyar and colleagues,21 and there was also a trend towards higher mortality in the older age groups in our study. However, the effect of age on SMR may be partly due to older age related comorbidity. Higher mortality for males and those with extensive disease has been reported7,16 but we found no impact of disease extent on SMR, and only a non‐significant rise in SMR for females. Older females, on the other hand, had a significantly higher SMR. However, as there was only a small number of deaths in this group, the finding may be coincidental.

Differences in drug treatment may influence mortality through therapeutic or adverse effects. The difference in treatment duration of 5‐ASA found between the patients who died and the survivors is probably of no clinical importance. The number of serious adverse events of possible importance to mortality was low compared with the extensive prescription of this group of drugs.24 The increase in GCS treatment found in patients who died during follow‐up could, however, be of some importance to mortality, even if this could not be established from our data. For AZA/6MP, the number of users may have been too small to detect any possible influence on mortality rate. Also, long term effects of drug treatment on mortality may not have been detectable in this study due to the short follow up period. Differences in drug treatments could also reflect differences in disease severity of importance to mortality. A difference in the incidence of ulcerative colitis between northern and southern European centres has been reported previously10 but we found no significant difference in SMR by place of residence, even though SMR was slightly higher for the northern than for the southern centres. But the lack of significance could be due to a type II statistical error.

Smoking has been suggested to be an important influence on mortality in ulcerative colitis. The lower mortality from cardiovascular and pulmonary disease in patients with ulcerative colitis has been attributed to the lower frequency of smoking in these patients, especially in comparison with patients with Crohn's disease.25,26 We found a higher pulmonary SMR, which reached a significant level for the Copenhagen cohort from the Danish centre, and this is in line with the findings of Winther and colleagues.7 There is no obvious explanation for this finding. Of the 11 patients who died from pulmonary disease, the cause of death was noted as pneumonia in eight and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in three patients. Possible local differences in registration of the primary cause of death or of the records on comorbidity in this elderly, probably multimorbid patient group, might have biased the result. Also, the smoking status of these patients might not have been substantially different from the total cohort, and therefore not in conflict with ulcerative colitis as being a disease of non‐smokers. Because data on smoking habits and comorbidity were not available, and the number of patients who died from pulmonary causes was low, this finding must be interpreted with caution.

It could be argued that the study shows that mortality in patients with ulcerative colitis who are “compliant” and attend follow‐up, answer questionnaires and attend centres with the logistics necessary to maintain follow‐up over a decade is normal. Mortality among the other patients could have made a difference. From the original cohort of patients described by Shivananda and colleagues,10 patients from centres who were in the follow‐up analysis did not differ in baseline characteristics, such as age, sex or north‐south location, compared with patients from centres that were not included. A similar uniformity in patient characteristics was found when comparing patients with unknown vital status to the rest of the patients included in the follow‐up study. Our data do not seems to indicate that these results on mortality were not representative of the original cohort, even if the follow‐up did not include all of the original centres.

Some of the subgroups may represent too small a sample for some analyses such as cause of mortality by sex, or mortality related to geographical region. The multivariate analysis was impeded by the relatively small number of deaths and the strong association between age and survival. There could have been a selection bias in the patients and centres participating in the follow‐up study but a uniform standard of clinical management of ulcerative colitis was noted in the first year in all of the centres participating in the original cohort.27

The high number of cases of proctitis, especially among females, could have biased the mortality rates found in our study. The initial disease distribution was however in line with what was previously found in the IBSEN cohort by Moum et al28 who reported an initial incidence of proctitis of 32%, and a male/female ratio of 0.7 We therefore believe that our data should be acceptable and justified with regards to the low risk of selection bias.

In conclusion, our prospective European population based cohort study of mortality in ulcerative colitis has shown no rise in SMR at any time over 10 years of observation. No rise in mortality was found from gastrointestinal diseases. There was a trend towards higher mortality with disease onset at an older age. Long term follow‐up studies of possible risk factors, such as drug treatment and smoking, for morbidity and mortality are needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the members of the EC‐IBD Study Group for their contribution to this work: Marina Beltrami, Tomm Bernklev, Vibeke Binder, Mercedes Butron, Mia Cilissen, Greet Claessens, Juan Clofent, Claudio Cortelezzi, Guiseppe d'Albasio, Michel Economou, Giovanni Fornaciari, Angie Harrington, Sofie Joosens, Kostas Katsanos, Ioannis Koutroubakis, Charles Limonard, Idar Lygren, Andrea Messori, Estella Monteiro, Ioannis Mouzas, Pia Munkholm, Maria Grazia Mortilla, Marius Nap, Paula Borrhalho Nunes, Victor Ruiz Ochoa, Colm ÒMorain, Athanasios Pallis, Angelo Pera, Santos Pereira, Asghar Quasim, Tullio Ranzi, Marielle Romberg, Maurice G. Russel, Jildou Sijbrandij, Epameinondas Tsianos, Maria Tzardi, Ed van Hees, Robert van Hees, Gilbert van Zeijl, Severine Vermeire, Ioannis Vlachonikolis, Frederik Wessels, Hagit Yona.

Abbreviations

5‐ASA - salazopyrine/5‐aminosalisylic acid

AZA/6MP - azathioprine/6‐mercaptopurine

CCS - clinical classification software

CRC - colorectal cancer

EC‐IBD - European Collaborative Study Group of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

GCS - glucocorticosteroids

SMR - standardised mortality ratio

Footnotes

The study was supported by the European Commission (QLG4‐CT‐2000‐01414).

Competing interests: None.

The study protocol was approved by the local committees for medical ethics for all participation centres.

References

- 1.Russel M G. Changes in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease: what does it mean? Eur J Intern Med 200011191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loftus E V., Jr Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology 20041261504–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M.et al Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology 19941073–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernklev T, Jahnsen J, Aadland E.et al Health‐related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease five years after the initial diagnosis. Scand J Gastroenterol 200439365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persson P G, Bernell O, Leijonmarck C E.et al Survival and cause‐specific mortality in inflammatory bowel disease: a population‐based cohort study. Gastroenterology 19961101339–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palli D, Trallori G, Saieva C.et al General and cancer specific mortality of a population based cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: the Florence Study. Gut 199842175–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winther K V, Jess T, Langholz E.et al Survival and cause‐specific mortality in ulcerative colitis: follow‐up of a population‐based cohort in Copenhagen County. Gastroenterology 20031251576–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stockbrugger R W, Russel M G, van Blankenstein M.et al EC‐IBD: a European effort in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Intern Med 200011187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lennard‐Jones J E. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 19891702–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shivananda S, Lennard‐Jones J, Logan R.et al Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease across Europe: is there a difference between north and south? Results of the European Collaborative Study on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC‐IBD). Gut 199639690–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolters F L, van Zeijl G, Sijbrandij J.et al Internet‐based data inclusion in a population‐based European collaborative follow‐up study of inflammatory bowel disease patients: description of methods used and analysis of factors influencing response rates. World J Gastroenterol 2005117152–7158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical Classifications Software for ICD‐10 Data: 2003 Software and User's Guide. January 2003. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005, http://www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/icd10usrgd.htm (last accessed 21 January 2007)

- 13.WHO The Tenth Revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD‐10); ISBN 92 4 154419. Geneva: WHO Press, 1992

- 14.Mortality Database, World Health Organization, July 2000. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005, http://www3.who.int/whosis/mort/table1.cfm?path = mort,mort_table1&language = english (last accessed 21 January 2007)

- 15.Breslow M D. Comparisons among exposure groups. In: Heseltine E, ed. Statistical methods in cancer research, the design and analysis of cohort studies. Lyon: Oxford University Press, 198648–79.

- 16.Brostrom O, Monsen U, Nordenwall B.et al Prognosis and mortality of ulcerative colitis in Stockholm County, 1955–1979. Scand J Gastroenterol 198722907–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ekbom A, Helmick C G, Zack M.et al Survival and causes of death in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population‐based study. Gastroenterology 1992103954–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gyde S, Prior P, Dew M J.et al Mortality in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 198283(Pt 1)36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Card T, Hubbard R, Logan R F. Mortality in inflammatory bowel disease: a population‐based cohort study. Gastroenterology 20031251583–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davoli M, Prantera C, Berto E.et al Mortality among patients with ulcerative colitis: Rome 1970–1989. Eur J Epidemiol 199713189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrokhyar F, Swarbrick E T, Grace R H.et al Low mortality in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease in three regional centers in England. Am J Gastroenterol 200196501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Probert C S, Jayanthi V, Wicks A C.et al Mortality in patients with ulcerative colitis in Leicestershire, 1972–1989. An epidemiological study. Dig Dis Sci 199338538–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russel M G, Stockbrugger R W. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: an update. Scand J Gastroenterol 199631417–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ransford R A J, Langman M S J. Sulphasalazine and mesalazine: serious adverse reactions re‐evaluated on the basis of suspected adverse reaction reports to the Committee on Safety of Medicines. Gut 200251536–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gyde S N, Prior P, Alexander F.et al Ulcerative colitis: why is the mortality from cardiovascular disease reduced? Q J Med 198453351–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masala G, Bagnoli S, Ceroti M.et al Divergent patterns of total and cancer mortality in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease patients: the Florence IBD study 1978–2001. Gut 2004531309–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lennard‐Jones J E, Shivananda S. Clinical uniformity of inflammatory bowel disease at presentation and during the first year of disease in the north and south of Europe. EC‐IBD Study Group. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 19979353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moum B, Ekbom A, Vatn M.et al Change in the extent of colonoscopic and histological involvement in ulcerative colitis over time. Am J Gastroenterol 1999941564–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]