Fibrosis and strictures are common and irreversible complications of Crohn's disease that potentially necessitate bowel resection. Tranilast, N‐(3',4'‐dimethoxycinnamoyl) anthranilic acid, inhibits keloid scar formation through the inhibition of production of metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase‐1 from neutrophils.1 Please check the phrase “inhibition of … neutrophils” is OK Tranilast has been shown to inhibit fibrosis in various experimental models.2,3,4 Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled studies have shown substantial inhibition by tranilast of restenosis of coronary arteries.5,6,7 A case report has demonstrated the efficacy of long‐term administration of tranilast in inflammatory endobronchial stenosis.8

Between June 2001 and July 2005, 24 patients with quiescent Crohn's disease with non‐symptomatic intestinal strictures were recruited. Baseline intestinal stricture was evaluated by small bowel barium enteroclysis, or Gastrografin® (Schering Aktiengesellschaft, Berlin, Germany) enteroclysis under endoscopic examination using a digital caliper (Digimatic® Caliper, Mitutoyo Corporation, Kawasaki, Japan). Patients were allocated using a random number table to receive tranilast 200 mg (2 tablets) after every meal, three times daily (tranilast group) or to a control group that did not receive the agent, and followed up prospectively. The primary endpoint was whether or not there was development of symptomatic stricture requiring hydrostatic balloon dilatation of the stricture or requiring surgical resection, which was quantified as the cumulative non‐symptomatic stricture rate. The secondary endpoint used in this study was the diameter of the stricture, which was measured at the time of recruitment (basal diameter) and at the time of development of symptomatic stricture or at the latest follow‐up (final diameter). Change in diameter during the follow‐up period was assessed using the equation (final diameter‐basal diameter/basal diameter) 100/month. The change in diameter was compared between groups (% change/month)

There was no significant difference in clinical backgrounds between the tranilast group and the control group (table 1). One patient in the tranilast group withdrew because of a reduced white blood cell count. During the observation period, one patient in the tranilast group and two in the control group received infliximab infusion, and two tranilast and one control patient had been taking oral prednisolone. Six tranilast and seven control patients had been taking immunomodulators (azathioprine or mercaptopurine there were no significant differences between groups for these factors.

Table 1 Clinical background of the patients.

| Characteristic | Tranilast group (n = 12) | Control group (n = 12) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (25th and 75th percentile) | 35.0 (26.5, 40.5) | 37.5 (33.5, 46.5) | 0.1183 |

| Male/female | 7/5 | 9/3 | 0.6650 |

| Median disease duration, years (25th and 75th percentile) | 7.3 (4.7, 10.5) | 11.5 (6.5, 13.5) | 0.2122 |

| Location of the disease | |||

| Ileitis | 3 | 7 | 0.0892 |

| Colitis | 4 | 0 | |

| Ileocolitis | 5 | 5 | |

| Behaviour of the disease | |||

| Stricturing | 7 | 4 | >0.9999 |

| Penetrating | 5 | 5 | |

| Location of stricture | |||

| Ileum | 7 | 8 | >0.9999 |

| Colon | 5 | 4 |

Differences between groups were analysed by one‐way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's correction. χ2 analysis was used for table analysis, and Fisher's exact test with Yates' correction was used. The cumulative non‐symptomatic stricture rate was assessed by the life‐table method employing Log rank (Mantel–Cox) analysis. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

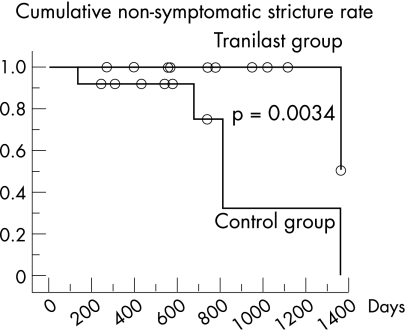

Hydrostatic balloon dilatation was done in one patient in the tranilast group and in five patients in the control group owing to the development of symptomatic stricture (fig 1, p = 0.0034). The median basal diameter of the stricture was 6.40 mm (25th percentile 4.25, 75th percentile 6.70) in the tranilast group and 6.35 mm (5.50, 7.25) in the control group (p = 0.3837). At follow‐up, the diameter of the stricture was 5.60 mm (4.25, 11.23) in the tranilast group and 5.05 mm (4.30, 7.10) in the control group (p = 0.1769). Change in diameter during the follow‐up period was 0.48% per month (–0.63, 3.18) in the tranilast group, compared with –0.86% per month (–2.11, 0.88) in the control group (p = 0.2740).

Figure 1 Cumulative non‐symptomatic stricture rate with and without oral tranilast administration. Patients taking tranilast had a significantly higher non‐symptomatic stricture rate compared with those not receiving this agent. The median observation period for the tranilast group was 782 (25th percentile 558, 75th percentile 1093) days, with a period of 559 (366, 738) days in the control group.

We found a preventive effect of tranilast on the development of symptomatic intestinal stricture in patients with Crohn's disease. Since there is no established effective medical therapy for intestinal stricture in Crohn's disease, long‐term tranilast administration has potential as a therapeutic modality for the prevention of the development of intestinal stricture in patients with Crohn's disease.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This study was approved by the ethical committee of Osaka City University and informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

References

- 1.Shimizu T, Kanaki K, Kyo Y.et al Effect of tranilast on matrix metalloproteinase production from neutrophils in‐vitro. J Pharm Pharmacol 20065891–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin J, Kelly D J, Mifsud S A.et al Tranilast attenuates cardiac matrix deposition in experimental diabetes: role of transforming growth factor‐beta. Cardiovasc Res 200565694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okada Y, Matsumura Y, Shimada K.et al Anti‐allergic agent tranilast decreases development of obliterative airway disease in rat model of heterotopic tracheal transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2004231392–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly D J, Zhang Y, Gow R.et al Tranilast attenuates structural and functional aspects of renal injury in the remnant kidney model. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004152619–2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosuga K, Tamai H, Ueda K.et al Effectiveness of tranilast on restenosis after directional coronary atherectomy. Am Heart J 1997134712–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamai H, Katoh O, Suzuki S.et al Impact of tranilast on restenosis after coronary angioplasty: tranilast restenosis following angioplasty trial (TREAT). Am Heart J 1999138968–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamai H, Katoh K, Yamaguchi T.et al The impact of tranilast on restenosis after coronary angioplasty: the Second Tranilast Restenosis Following Angioplasty Trial (TREAT‐2). Am Heart J 2002143506–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yanagihara K, Matsuoka K, Hanaoka N.et al Inflammatory endobronchial stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 200171698–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]