Abstract

Background/aim

X linked retinoschisis (XLRS) is caused by mutations in RS1 which encodes the discoidin domain protein retinoschisin, secreted by photoreceptors and bipolar cells. Missense mutations occur throughout the gene and some of these are known to interfere with protein secretion. This study was designed to investigate the functional consequences of missense mutations at different locations in retinoschisin.

Methods and results

The authors developed a structural model of the retinoschisin discoidin domain and used this to predict the effects of missense mutations. They expressed disease associated mutations and found that those affecting conserved residues prevented retinoschisin secretion. Most of the remaining mutations cluster within a series of loops on the surface of the β barrel structure and do not interfere with secretion, suggesting this region may be a ligand binding site. They also demonstrated that wild type retinoschisin octamerises and associates with the cell surface. A subgroup of secreted mutations reduce oligomerisation (C59S, C219G, C223R).

Conclusions

It is suggested that there are three different molecular mechanisms which lead to XLRS: mutations interfering with secretion, mutations interfering with oligomerisation, and mutations that allow secretion and oligomerisation but interfere with retinoschisin function. The authors conclude that binding of oligomerised retinoschisin at the cell surface is important in its presumed role in cell adhesion.

Keywords: X linked retinoschisis, retinoschisin, discoidin domain

X linked recessive juvenile retinoschisis is the leading cause of juvenile macular degeneration in males and is characterised by schisis within the retina, leading to visual deterioration.1,2,3 Affected males have reduced b‐waves but normal a‐waves on electroretinogram indicating an inner retinal abnormality.4,5

A large number of disease causing mutations in the gene RS1 are recognised6 (www.dmd.nl/rs/rshome.html), the majority being missense substitutions. RS1 encodes retinoschisin, a protein of unknown function secreted from photoreceptor and bipolar cells7,8 and contains a discoidin domain.9 Discoidin domains are implicated in cell adhesion or cell signalling.10,11 The Rs1h knockout RS mouse has a retinal phenotype closely resembling the human disease with a generalised disruption of retinal cell layers.12 Replacement of the RS1 gene leads to an improvement in retinal function and morphology,13,14 supporting a role for retinoschisin in retinal architecture development through mediating interactions between cells and extracellular matrix.

RS mutations cluster within the discoidin domain. We have previously shown that many mutations lead to intracellular retention and degradation of mutant protein.15 Recent work indicates that retinoschisin functions as an octamer.16,17

We describe work confirming and extending these data. We present our own structural model of the retinoschisis discoidin domain and interpret disease mutations with respect to the model. We describe data confirming retinoschisin octamerisation and cell surface association and our expression of mutations15). We use our data and those of others16,17 to discuss potential molecular mechanisms leading to the disease.

Material and methods

A homology based model of the retinoschisin discoidin domain was constructed with 3D‐PSSM18 webserver (www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/∼3dpssm) using as a scaffold the structure of the factor Va C2 domain,19 entry 1CZS in the PDB.20

Construction of mutant RS1 by site directed mutagenesis

Constructs of RS1 mutations were generated by site directed mutagenesis using QuikChange (Stratagene) as described,15 genbank:cDNA NM 000330, protein NP 000321.

Cell culture and transfection

COS‐7 cells were grown and transfected15; 72 hours after transfection, cells and culture medium were collected. Stable cell lines expressing wild type and mutant proteins (C56S, R141H and F108C) were selected by G148.

Western blot analysis

Whole cell lysates were prepared and blotted.15 For non‐reducing SDS‐PAGE, samples were denatured in Laemmli buffer (room temperature 30 minutes) with 20 mM N‐ethylmaleimide (NEM) but without β‐mercaptoethanol.

Gel filtration analysis

Gel filtration analysis was performed on a Superdex 200 column at room temperature after equilibration with 20 mM TRIS‐HCl, 0.15M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, calibrated by molecular weight markers. Cell culture medium was concentrated to 1 ml by Vivaspin (Vivascience) and applied onto the gel filtration column. Fifty fractions were collected, with 1.5 ml per fraction.

Cell surface biotinylation

Cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/ml sulfo‐NHS‐LC‐biotin in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C for 30 minutes, washed with cold PBS containing 100 mM glycine, lysed with RIPA buffer. A volume of 150 μl of total cell lysate fraction was incubated with equal volumes of streptavidin‐sepharose overnight, spun at 15 000 g at 4°C for 15 minutes (supernatant = intracellular fraction). Pelleted streptavidin beads were washed with RIPA buffer and biotinylated cell surface proteins eluted by heating in 150 μl Laemmli buffer at 100°C for 5 minutes. Samples of cell fractions were subjected to SDS‐PAGE followed by western blot. Calnexin antibody (Santa Cruz) 1:500 dilution was used to detect calnexin as an intracellular control.

Results

The C2 domain of factor Va19 was chosen as the scaffold for homology modelling of the retinoschisin discoidin domain because it is the most closely related protein of known structure, (37% sequence identity). The goal was to construct a model showing the location of disease associated mutations within the overall fold. After we completed this modelling, similar homology based molecular models were published by two other groups.16,21

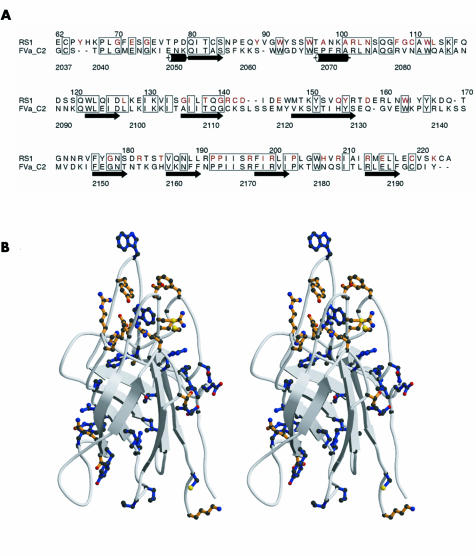

The model was examined using computer graphics, highlighting residues substituted in RS missense mutations. A number of these residues are identical in the aligned sequences of retinoschisin and factor Va (fig1A); the majority of these are buried in the hydrophobic core (fig 1B), so one would predict that mutations would destabilise the structure leading to intracellular retention as we have previously shown.15 Strikingly, most of the remaining (unconserved) mutations cluster within a series of loops on one end of the discoidin domain, comprising residues 85–96, 102–121, 141–147, 181–185, and 203–212 (fig 1B). The clustering on the surface suggested that this region may be a ligand binding site.

Figure 1 Homology based modelling of discoidin domain of retinoschisin. (A) Alignment of amino acid sequences of discoidin domains of retinoschisin (RS1) and factor Va (FVa_C2), prepared with Alscript. Boxes outline residues that are identical in the two sequences, retinoschisin residues mutated in disease are highlighted in red, and the secondary structure of the factor Va crystal structure19 indicated schematically. (B) Ribbon diagram (as stereo pair) of the homology based model of the retinoschisin discoidin domain showing the β barrel structure with long loops, prepared with Molscript (www.avatar.se/molscript) . The side chains shown indicate the positions of all mutations in retinoschisin patients to date. Sites of mutation that are conserved in the sequence alignment with factor Va are shown in blue, while mutation sites that are not conserved are shown in orange.

Analysis of the secretion profile of mutant retinoschisin

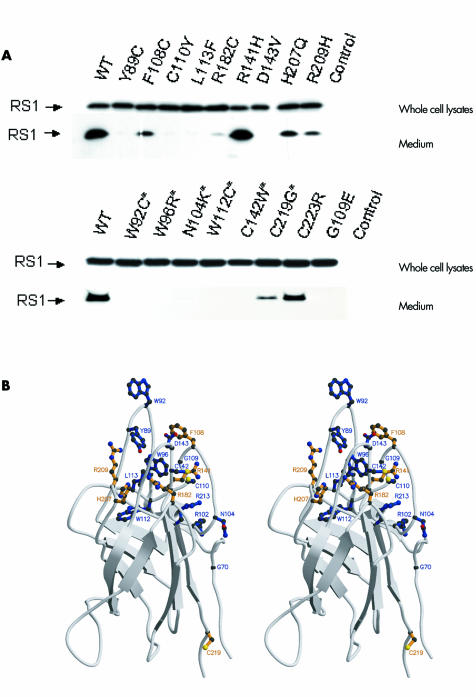

We expressed 24 mutant forms of retinoschisin, seven of which had been published previously15 and analysed the medium for secretion (table 1 and fig 2). The mutations encompassed those altering conserved and non‐conserved residues within the discoidin domain, those affecting cysteine residues throughout the molecule, and one signal peptide mutation.

Table 1 Secretion profile of mutant retinoschisin.

| Mutations | Base changes | Amino acid changes | Secretion | Mutation affects conserved residue | Discoidin domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L12H* | GGG‐GAG | Leu‐His | − | − | No |

| C59S* | TGT‐AGT | Cys‐Ser | + | − | No |

| G70S* | TGT‐AGT | Gly‐Ser | − | + | Yes |

| Y89C | TAT‐TGT | Tyr‐Cys | − | − | Yes |

| W92C | TGG‐TGC | Trp‐Cys | − | + | Yes |

| W96R | TGG‐CGG | Trp‐Arg | − | + | Yes |

| R102W* | CGG‐TGG | Arg‐Trp | − | + | Yes |

| N104K | AAC‐AAG | Asn‐Lys | − | + | Yes |

| F108C | TTT‐TGT | Phe‐Cys | + | − | Yes |

| G109R* | GGG‐CGG | Gly‐Arg | − | − | Yes |

| G109E | GGG‐GAG | Gly‐Glu | − | − | Yes |

| C110Y | TGT‐TAT | Cys‐Tyr | − | − | Yes |

| W112C | TGG‐TGT | Trp‐Cys | − | + | Yes |

| L113F | CTC‐TTC | Leu‐Phe | − | − | Yes |

| R141H | CGC‐CAC | Arg‐His | + | − | Yes |

| R141G* | CGC‐GGC | Arg‐Gly | + | − | Yes |

| C142W* | TGT‐TGG | Cys‐Trp | − | + | Yes |

| D143V | GAC‐GTC | Asp‐Val | − | − | Yes |

| R182C | CGC‐TGC | Arg‐Cys | + | − | Yes |

| H207Q | CAC‐CAG | His‐Gln | + | − | Yes |

| R209H | CGC‐CAC | Arg‐His | + | − | Yes |

| R213W | CGG‐TGG | Arg‐Trp | − | + | Yes |

| C219G | TGC‐GGC | Cys‐Gly | + | + | Yes |

| C223R | TGT‐CGT | Cys‐Arg | + | − | No |

*Published previously.15

Figure 2 Western blot of expressed mutant retinoschisin. (A) Whole cell lysates and cell culture medium of wild type and mutant retinoschisin were subjected onto SDS‐PAGE and immunoblotted using anti‐retinoschisin antibody. *Indicates mutations at conserved residues in discoidin domain. “Control” indicates transfection with pcDNA 3.1 empty vectors only. Six of the 12 mutations affecting non‐conserved residues and two mutations affecting the cysteines outside the discoidin domain (C59 and C223) were secreted. (B) Ribbon diagram (as stereo pair) showing side chains for residues investigated. Sites of mutation that interfered with secretion of the mutant protein are shown in blue, while mutation sites that did not interfere with secretion are shown in light orange.

Three mutations (L12H, C59S, and C223R) are outside the discoidin domain and one (L12H) inhibits cleavage of the signal peptide.15 We confirmed that C59S15 and C223R did not interfere with secretion.16 Of the nine mutations affecting conserved residues, one, C219G, was successfully secreted while eight resulted in intracellular retention (table 1 and fig 2). Twelve mutations affected non‐conserved residues, of which six (F108C, R141H, R141G, R182C, H207Q, R209H) were secreted. These are predicted to cluster at the loop region (fig 2B). Y89 and W92, also found in the loop region, were mutated to cysteine, so their failure to be secreted may be the result of aggregation through the formation of inappropriate disulfide bridges.

Retinoschisin associates with the cell surface

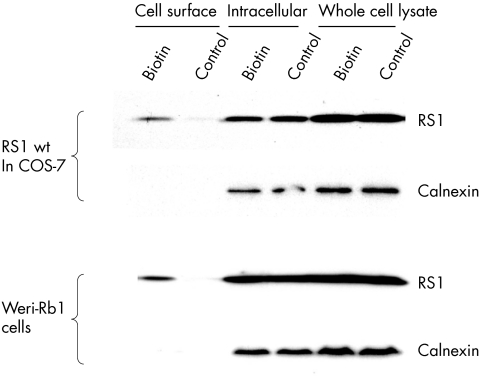

We investigated whether wild type retinoschisin interacts with the cell surface (fig 3). We biotin labelled cell surface proteins and captured these by streptavidin coated sepharose beads. Retinoschisin was present in the cell surface fraction, cell lysate, and medium indicating it is associated with the cell membrane after secretion unlike the intracellular control calnexin. As retinoschisin is a secretory protein this suggests that anchoring to the cell membrane is through interaction with other molecules.

Figure 3 Biotinylation of cell surface proteins. Following biotinylation cells were lysed and fractionated. Control cells were not exposed to biotin but otherwise followed the same protocol. Western blot analysis was used to detect the presence of retinoschisin, or the intracellular control protein (calnexin). Retinoschisin was detected in all fractions including the cell surface in the biotinylated cells but not on the cell surface of the control cells. Calnexin was not detected in the cell surface fractions.

Octamerisation of retinoschisin

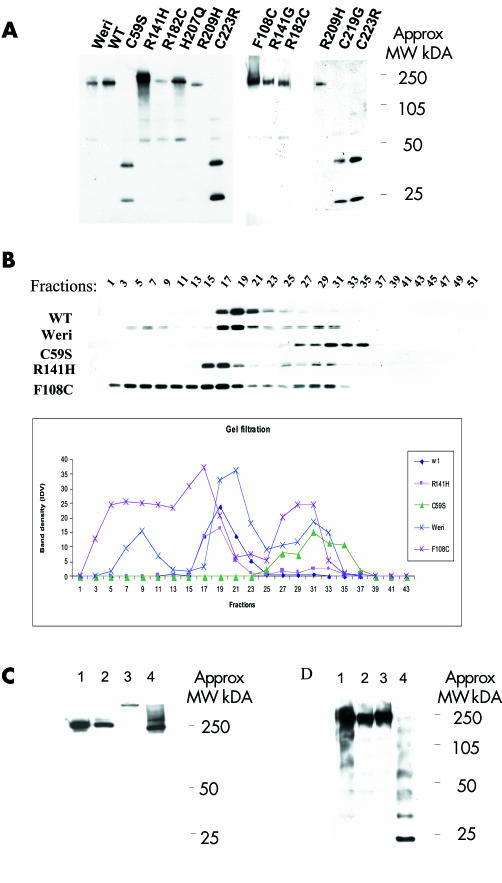

Retinoschisin is predicted to form oligomers.7,16 We investigated this for wild type retinoschisin and the secreted mutants using a combination of non‐reducing PAGE (fig 4A) and gel filtration (fig 4B). The results confirm that retinoschisin does form oligomers (MW approximately 250 kDa) and that three of the cysteine substitution mutants (C59S, C219G, and C223R) fail to form oligomers of the same size.

Figure 4 Non‐reducing gel and gel filtration for secreted wild type (WT) retinoschisin, retinoschisin mutants, and Weri‐Rb1 Retinoschisin. (A) Non‐reducing gel for WT and mutant retinoschisin showing oligomerisation of WT and mutants. Three of the mutants (C59S, C219G, and C223R) formed only monomers and dimers. (B) Gel filtration analysis using concentrated cell culture media from Weri‐Rb1 cells, stably transfected wild type RS1 and C59S, F108C and R141H mutants. 50 fractions were collected. The results of western blot analysis are shown from alternate fractions in the upper panel and indicate WT retinoschisin (and R141H) forms oligomers. C59S is detected in later fractions consistent with monomers, whereas F108C is eluted in earlier fractions indicating a greater tendency to oligomerisation than WT. The lower panel depicts the same data in graph form. (C) Non‐reducing gel analysing fractions from gel filtration. Lanes 1 and 2 show fractions 19 from Weri‐Rb1 cells and COS‐7 cells stably expressing WT retinoschisin respectively and lanes 3 and 4 show fractions 5 and 17 from COS‐7 cells stably expressing F108C retinoschisin, respectively. F108C mutant retinoschisins from fraction 5 runs slower than the other fractions indicating a larger sized multimer. (D) Non‐reducing gel demonstrating the effects of heating and NEM treatment on the WT retinoschisin. Each lane contains conditioned WT cell medium. Lane 1 unheated and untreated, lane 2 treated with NEM in 4M urea at room temperature, lane 3 treated with NEM in 4M urea and heated to 100°C for 3 minutes, lane 4 heated to 100°C for 3 minutes without NEM or urea. Laddering indicating dissociation of the oligomer is seen in lane 4 only.

The majority of wild type retinoschisin in Weri‐Rb1 cells, the stable transfected COS‐7 cell line and R141H was eluted in fractions 17–19. The estimated molecular weight of these fractions was surprisingly low (approximately 66 kDa) but re‐analysis by non‐reducing PAGE revealed the band had the same mobility as the large molecular weight band described above. Retinoschisin was consistently eluted in later fractions than expected which may indicate the protein is adhering to the gel matrix. For C59S most of the protein was eluted later still indicating an interference with full oligomerisation. F108C was eluted earlier indicating larger oligomers than both wild type and other mutants tested. This was confirmed by the re‐analysis of the peak fractions by non‐reducing PAGE (fig 4C). Interestingly, in the Weri‐Rb1 cells some wild type retinoschisin was eluted in earlier fractions 3–7 suggesting that some retinoschisin may be associating with another protein within the Weri‐Rb1 medium not present in the COS‐7 medium.

We noted that heating interfered with the stability of the oligomer. We investigated the effects of heating and treatment with the sulfhydryl modifying agent NEM (fig 4D) and confirmed this was due to interference of free cysteine residues with disulphide bonds. When the sample (fraction 19) was treated with NEM before heating a single high molecular weight band was observed (fig 4D) indicating the modification of the sulfhydryl groups of the free cysteine residues prevented their competing for disulphide bond formation. Heating in the absence of NEM reveals a laddering of eight bands confirming octamerisation.

Discussion

Mutations in retinoschisin lead to X linked retinoschisis,6,9 which causes retinal splitting.22 In addition, the knockout mouse model has a generalised disruption of retinal layers,12 suggesting that retinoschisin, like other discoidin domain proteins, has a role in cell adhesion and is involved in controlling the development and maintenance of retinal architecture.

The retinoschisin discoidin domain has strong homology to discoidin domains of other proteins, which allowed us to generate a model showing the location of disease associated mutations. Our model, derived separately from those of other groups,16,21 shows a similar structure and allowed us to identify for the first time the position of disease associated missense mutations within the model. This enabled us to correlate the effects of mutation position with successful secretion from cells. A subset of missense mutations did not interfere with secretion and the majority of these affected surface residues within the loop region (F108C, R141H, R141G, R182C, H207Q, and R209H), suggesting a functional rather than structural importance for this region. This provides both theoretical and experimental evidence supporting existence of a functional binding pocket lying closely linked to a hydrophobic surface region.

Wu and Molday have published elegant data describing the octamerisation of retinoschisin and the underlying disulphide bonding.17 They expressed mutant forms of retinoschisin and interestingly a comparison of their published data and our data indicates that different mutations affecting the same residue have a different consequence—that is, R141G and R141H are both secreted (data shown here) but R141C is not.17 This suggests that the addition of this cysteine may lead to the formation of abnormal disulphide bridges giving intracellular aggregation. In addition, our results differed for one mutation, R182C, for which we detected secretion at a low level and could concentrate this to a similar level to other secreted protein, whereas Wu et al failed to detect secretion. This may be because of differences in methodology. F108C showed an increase in oligomerisation. We hypothesise that this additional cysteine residue is available for disulphide bond formation and leads to aggregation.

Reviewing our own data and those of Wu et al we suggest three mechanisms of disease causation.

Mutations interfering with retinoschisis secretion

Mutations interfering with retinoschisin octamerisation

Mutations that allow secretion and octamerisation but interfere with protein function.

We have considered disease expression for patients with mutations in each of these groups and have found no correlation between the molecular mechanism and severity.23 This suggests there may be other factors influencing disease severity such as genetic modifiers or environmental influences. Recent work describing the successful treatment of knockout mice with targeted gene therapy13,14 indicates this may be a possible future therapy for patients. Since women who are heterozygous for the mutant gene (and therefore express both mutant and wild type retinoschisin) do not have retinal pathology, this suggests there is unlikely to be a detrimental interaction between the patient's own mutant retinoschisin and retinoschisin delivered from gene therapy. As we cannot predict disease severity such treatment would have to be considered on an individual basis. Molecular genetic testing in XLRS has facilitated diagnosis and improved genetic counselling for families. However, our current understanding of XLRS molecular pathology is still limited and further comprehensive analysis of retinoschisin and potential binding partners is important.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Bernard Weber (Universitsät Wurzburg, Germany) for providing the RS1 cDNA clone and to Graeme Black (Manchester University) for helpful advice and comments on the manuscript. This study was funded by the Medical Research Council UK. RJR is supported by a Principal Research Fellowship from the Wellcome Trust.

Abbreviations

NEM - N‐ethylmaleimide

XLRS - X linked retinoschisis

References

- 1.George N D, Yates J R, Moore A T. X linked retinoschisis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:697–702. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.7.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.George N D, Yates J R, Moore A T. Clinical features in affected males with X‐linked retinoschisis. Arch Ophthalmol 1996114274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seiving P A. Juvenile retinoschisis. In: Traboulsi E, ed. Genetic diseases of the eye. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998347–356.

- 4.Peachey N S, Fishman G A, Derlacki D J.et al Psychophysical and electroretinographic findings in X‐linked juvenile retinoschisis. Arch Ophthalmol 1987105513–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradshaw K, George N, Moore A.et al Mutations of the XLRS1 gene cause abnormalities of photoreceptor as well as inner retinal responses of the ERG. Doc Ophthalmol 199998153–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. The Retinoschisis Consortium, Functional implications of the spectrum of mutations found in 234 cases with X‐linked juvenile retinoschisis (XLRS). Human Molecular Genetics 199871185–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grayson C, Reid S N, Ellis J A.et al Retinoschisin, the X‐linked retinoschisis protein, is a secreted photoreceptor protein, and is expressed and released by Weri‐Rb1 cells. Hum Mol Genet 200091873–1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molday L L, Hicks D, Sauer C G.et al Expression of X‐linked retinoschisis protein RS1 in photoreceptor and bipolar cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200142816–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sauer C G, Gehrig A, Warneke‐Wittstock R.et al Positional cloning of the gene associated with X‐linked juvenile retinoschisis. Nat Genet 199717164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumgartner S, Hofmann K, Chiquet‐Ehrismann R.et al The discoidin family revisited: New members from prokaryotes and a homology based fold prediction. Protein Sci 199871626–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogel W. Discoidin domain receptors: structural relations and functional implications. FASEB J 199913S77–S82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber B H, Schrewe H, Molday L L.et al Inactivation of the murine X‐linked juvenile retinoschisis gene, Rs1h, suggests a role of retinoschisin in retinal cell layer organization and synaptic structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002996222–6227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng Y, Takada Y, Kjellstrom S.et al RS‐1 gene delivery to an adult Rs1h Knockout mouse model restores ERG b‐wave with reversal of the electronegative waveform of X‐linked retinoschisis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004453279–3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Min S H, Molday L L, Seeliger M W.et al Prolonged recovery of retinal structure/function after gene therapy in an Rs1h‐deficient mouse model of X‐linked juvenile retinoschisis. Mol Ther 2005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Wang T, Waters C T, Rothman A M.et al Intracellular retention of mutant retinoschisin is the pathological mechanism underlying X‐linked retinoschisis. Hum Mol Genet 2002113097–3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu W W, Molday R S. Defective discoidin domain structure, subunit assembly, and endoplasmic reticulum processing of retinoschisin are primary mechanisms responsible for X‐linked retinoschisis. J Biol Chem 200327828139–28146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu W W, Wong J P, Kast J.et al RS1, a discoidin domain‐containing retinal cell adhesion protein associated with X‐linked retinoschisis, exists as a novel disulfide‐linked octamer. J Biol Chem 200528010721–10730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelley L A, MacCallum R M, Sternberg M J. Enhanced genome annotation using structural profiles in the program 3D‐PSSM. J Mol Biol 2000299499–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macedo‐Ribeiro S, Bode W, Huber R.et al Crystal structures of the membrane‐binding C2 domain of human coagulation factor V. Nature 1999402434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berman H M, Westbrook J, Feng Z.et al The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res 200028235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fraternali F, Cavallo L, Musco G. Effects of pathological mutations on the stability of a conserved amino acid triad in retinoschisin. FEBS Lett 200354421–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirsch L S, Brownstein S, de Wolff‐Rouendaal D. A histopathological, ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of congenital hereditary retinoschisis. Can J Ophthalmol 199631301–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pimenides D, George N D L, Yates J R W.et al X‐linked retinoschisis: clinical phenotype and RS1 genotype in 86 UK patients. J Med Genet 200542e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]