Abstract

Aims

This study investigated the expression and localisation of thrombospondin‐1 (TSP‐1), a known anti‐angiogenic extracellular matrix protein, in normal aged control human eyes and eyes with age related macular degeneration (AMD).

Methods

Immunohistochemical analysis with mouse anti‐human TSP‐1 antibody and mouse anti‐human CD 34 antibody, as a blood vessel marker, was performed on frozen sections from macular and peripheral blocks of aged control donor eyes (n = 12; mean age 78.8 years), and eyes with AMD (n = 12; mean age 83.9 years). Pigment in retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and choroidal melanocytes was bleached. Three independent observers scored the immunohistochemical reaction product.

Results

In the macular region, TSP‐1 expression was observed intensely in Bruch's membrane and weakly in RPE basement membrane, choriocapillaris, and the wall of large choroidal blood vessels in the aged control eyes. In eyes with AMD, TSP‐1 immunoreactivity was significantly lower in all structures except RPE basement membrane (p<0.01). There was significantly lower TSP‐1 in the far periphery than the equator and submacular regions in all eyes. TSP‐1 immunoreactivity was low in choroidal neovascularisation (CNV), but it was high and diffuse in adjacent scar tissue.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that decreased TSP‐1 in Bruch's membrane and choroidal vessels during AMD may permit the formation of CNV.

Keywords: age related macular degeneration, choroidal neovascularisation, thrombospondin‐1, extracellular matrix, Bruch's membrane

Angiogenic ocular diseases, especially age related macular degeneration (AMD), are a leading cause of blindness in the elderly population in western world.1 It has been suggested that the balance between pro‐angiogenic and anti‐angiogenic factors controls angiogenesis and disruption of this balance causes angiogenesis including choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) in AMD.2 Recently, we demonstrated that expression of two potent anti‐angiogenic factors, endostatin and pigment epithelium derived factor (PEDF), in Bruch's membrane and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is significantly decreased in eyes with AMD.3,4

A number of age related changes have been described in Bruch's membrane,5,6,7,8 including drusen and basal laminar deposits.9,10,11 It has been suggested that Bruch's membrane functions as a physical barrier to the egress of cells and blood vessels from choroid into the sub‐RPE and subretinal spaces. Disruption of, or damage to, this barrier often results in the growth of CNV into the sub‐RPE and/or subretinal spaces.

Thrombospondin‐1 (TSP‐1), a major component of platelet α‐granules,12,13 is a 450 kDa multifunctional extracellular matrix (ECM) glycoprotein produced by endothelial cells,14 monocytes/macrophages,15 smooth muscle cells,16 and RPE cells.17 It is known to be a potent imhibitor of angiogenesis in vitro18,19,20 and in vivo.18,21 It has been suggested that TSP‐1 expression in the RPE layer may be involved in the prevention of CNV formation.17,22

We speculated that the tendency of new vessels to breach the submacular Bruch's membrane, as opposed to the extramacular regions, might be the result of regional differences in the expression of TSP‐1 in Bruch's membrane. However, distribution and relative levels of TSP‐1 expression in normal aged and AMD eyes are unknown. This study is designed to investigate the localisation of TSP‐1 in normal aged human eyes and eyes with AMD and to determine if any changes are apparent between the two groups.

Materials and methods

Donor eyes

Human donor eyes were obtained from the Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute and the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI; Philadelphia, PA, USA). Eyes of the following donors were used in the study: 12 subjects with AMD (age range 61–105 years; mean age 83.9 years); 12 aged control donors (age range 70–86 years; mean age 78.8 years) with no history of chorioretinal disease. One eye from a 3 year old subject was included for an age comparison. Characteristics of each subject are shown in table 1. The protocol of the study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki regarding research involving human tissue. The diagnosis of AMD was made by reviewing systemic and ocular medical history on the eye bank transmittal sheet or ocular history from the ophthalmologist and the postmortem gross examination of posterior eyecup, using transmitted and reflected illumination with a dissecting microscope (Stemi; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc, Thornwood, NY, USA).

Table 1 Characteristics of human donor cryopreserved eyes.

| Case | Time (hours) | Age/race/sex | Primary cause of death | Medical history | Ocular diagnosis | Ocular history | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DET | PMT | ||||||

| Normal | |||||||

| 1 | 5.5 | 24 | 3/B/M | Trauma | Sickle cell trait, asthma | Normal | |

| 2 | 6 | 29 | 70/W/M | MI | HT, prostate cancer | Normal | Unknown |

| 3 | ? | ? | 73/W/F | Colon cancer | Normal | Unknown | |

| 4 | 2.5 | 33 | 75/W/F | Heart disease | Normal | ||

| 5 | 7 | 27 | 76/W/F | Lung cancer | HT, CNF | Normal | |

| 6 | 1 | 26 | 77/W/M | COPD | HT | Normal | Unknown |

| 7 | 4 | 26 | 79/W/M | Respiratory failure | Normal | Cataract | |

| 8 | 2.5 | 28 | 80/W/M | COPD | Normal | Cataract | |

| 9 | 7.15 | 28 | 80/W/M | Intracranial haemorrhage | HT, angioplasty | Normal | IOL |

| 10 | 3 | 15 | 82/W/M | Metastasis brain cancer | Normal | ||

| 11 | 3 | 16 | 83/W/M | Cardiac respiratory arrest | Normal | IOL | |

| 12 | 4 | 31 | 84/W/M | Cardiac arrhythmia | Parkinson's disease | Normal | IOL |

| 13 | 5 | 26 | 86/W/F | Respiratory failure | Normal | ||

| AMD | |||||||

| 14 | 3.5 | 34 | 61/W/M | Metastasis oesophageal cancer | AMD, early | Radial keratotomy | |

| 15 | 3.5 | 42 | 69/W/F | Subarachnoid haemorrhage | Pulmonary fibrosis, hypothyroidism | AMD (GA), late | Macular degeneration |

| 16 | 4 | 33 | 74/W/M | Prostate cancer | AMD, early | Macular degeneration; IOL | |

| 17 | 7 | 30 | 75/W/M | Aspiration pneumonia | AMD (GA), late | Macular degeneration | |

| 18 | 3 | 33 | 79/W/M | Pneumonia | HT, asthma, prostate cancer | AMD, early | Macular degeneration; IOL |

| 19 | 5 | 29 | 81/W/F | Myocardial infarction | HT | AMD, early | Macular hole |

| 20 | 3 | 12 | 83/W/M | Prostate cancer | DM, HT | AMD, early | Cataract + maculopathy |

| 21 | 4 | 20 | 93/W/F | Multisystem failure | DM, HT | AMD (disciform scar), late | Macular degeneration |

| 22 | 3 | 36 | 94/W/M | Cardiac failure | AMD (disciform scar), late | Macular degeneration; IOL | |

| 23 | 3.5 | ? | 95/W/M | Cardiomyopathy | AMD (disciform scar), late | Legally blind | |

| 24 | 2 | 33 | 98/W/F | Old age | AMD, early | IOL | |

| 25 | 5 | 11 | 105/W/M | COPD | AMD (disciform scar, GA) | Unknown | |

DET, death to enucleation time; PMT, postmortem time (death to fixation); W, white; B, black (African American); M, male; F, female; AMD, age related macular degeneration; MI, myocardial infarction; CNF, congenital nephrotic syndrome; DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GA, geographic atrophy; IOL, intraocular lens.

Tissue preparation

After the anterior segment of the eye was removed, posterior eyecups were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 1 hour, cryopreserved with increasing concentrations of sucrose, and serially sectioned as previously described.23 To clarify regional differences in the expression of TSP‐1 in Bruch's membrane, we examined the choroidal tissue sections from both the inferior macula (all eyes) and the nasal periphery (seven of 12 of normal aged; nine of 12 of eyes with AMD) in this study.

Immunohistochemistry

Streptavidin alkaline phosphatase (APase) immunohistochemistry was performed on 8 µm cryosections using a nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) development system as previously described3 with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti‐human thrombospondin (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and mouse anti‐human CD34 antibody (1:800; Signet Laboratory, Dedham, MA, USA), as a blood vessel marker in adjacent sections. As a negative control, the primary antibody was omitted and no staining was observed (data not shown). The pigment was bleached from RPE and choroidal melanocytes as described previously.3

Three independent masked observers, using a previously described grading system,3,24 graded blindly the relative intensity of the immunoreactivity for TSP‐1 antibody in different structures.

Statistical analysis

Mean score (SD) from the graders was calculated for each retinal and choroidal structure. Probabilities were determined by comparing mean scores from the aged control eyes with scores from eyes with AMD using the Student's t test and assuming unequal variance and two tails. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to determine the geographic differences in TSP‐1 expression in Bruch's membrane in fellow eyes. The p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Localisation of TSP‐1 in normal aged retina and choroid at equator region

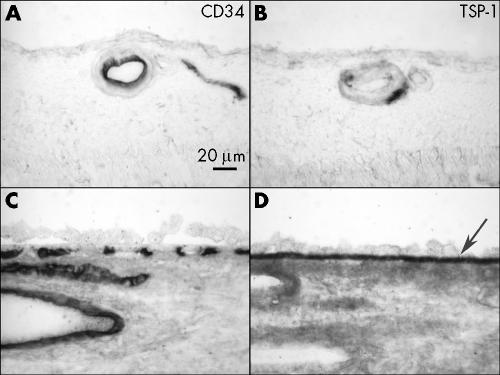

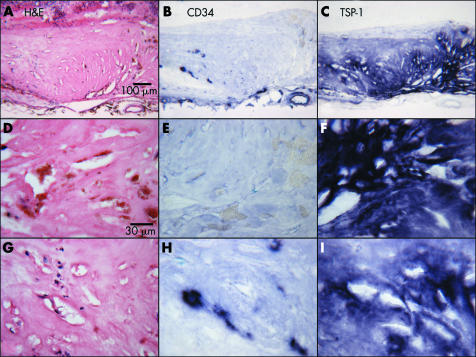

Moderate TSP‐1 staining was observed in the wall of large retinal blood vessels and weak staining in inner limiting membrane in normal aged control retina (fig 1B). No other remarkable immunolabelling was observed in the neural retina. The most intense TSP‐1 staining in the choroid was associated with Bruch's membrane (fig 1D). Moderate staining was observed in choriocapillaris, the wall of choroidal large vessels, and choroidal stroma. CD34 was localised in endothelial cells of retinal blood vessels (fig 1A), choriocapillaris, and large choroidal blood vessels (fig 1C). Intense small spots of TSP‐1 immunoreactivity observed in lumens of retinal and choroidal blood vessels appeared to be platelets, which are a major source of TSP‐1 in the blood.

Figure 1 Immunolocalisation of TSP‐1 in retina and choroid of a normal aged control eye (case 12). TSP‐1 is present in the wall of retinal blood vessels (B), RPE basal lamina, Bruch's membrane (arrow), choriocapillaris, and the wall of choroidal blood vessels (D). Immunostaining of CD34 demonstrate retinal blood vessels (A), choriocapillaris, and large choroidal blood vessels (C).

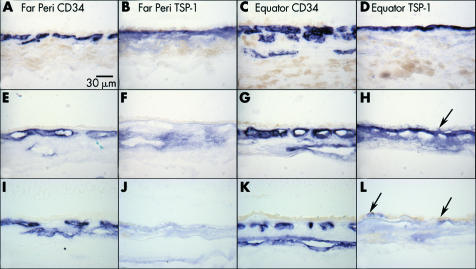

To determine if the level of TSP‐1 in Bruch's membrane was influenced by normal ageing, we examined the choroidal tissue from a 3 year old subject with sickle cell trait. In the 3 year old eye, intense immunostaining of TSP‐1 antibody was observed in Bruch's membrane at the equator (fig 2D) whereas, moderate staining in Bruch's membrane and choriocapillaris in far periphery (fig 2B). In aged control eyes, weak to almost negative TSP‐1 staining was observed in Bruch's membrane in the far periphery compared to the 3 year old eye (fig 2F); however, the immunoreactivity in the aged choroid was more diffuse and associated with choroidal stroma. There was no difference in TSP‐1 staining levels in Bruch's membrane at the equatorial region between young and aged control subjects (fig 2D and H).

Figure 2 Distribution of TSP‐1 in the choroid. TSP‐1 expression in the choroid from a 3 year old eye (A–D; case 1), a normal 70 year old eye (E–H; case 2), and an 81 year old eye with early AMD (I–L; case 19). Immunoreactivity for TSP‐1 is intense at the equator and faint at ora serrata in Bruch's membrane of both young (B, D) and aged control (F, H) eyes. No dramatic change in TSP‐1 staining is observed between young and old eyes at the equator. In the early AMD eye, no remarkable TSP‐1 staining is observed in the far periphery (J) or at the equator (L). Negative to faint TSP‐1 staining is observed in RPE both in aged control eyes (H, arrow) and eyes with early AMD (L, arrow). CD 34 staining shows choriocapillaris and large choroidal blood vessels (A, C, E, G).

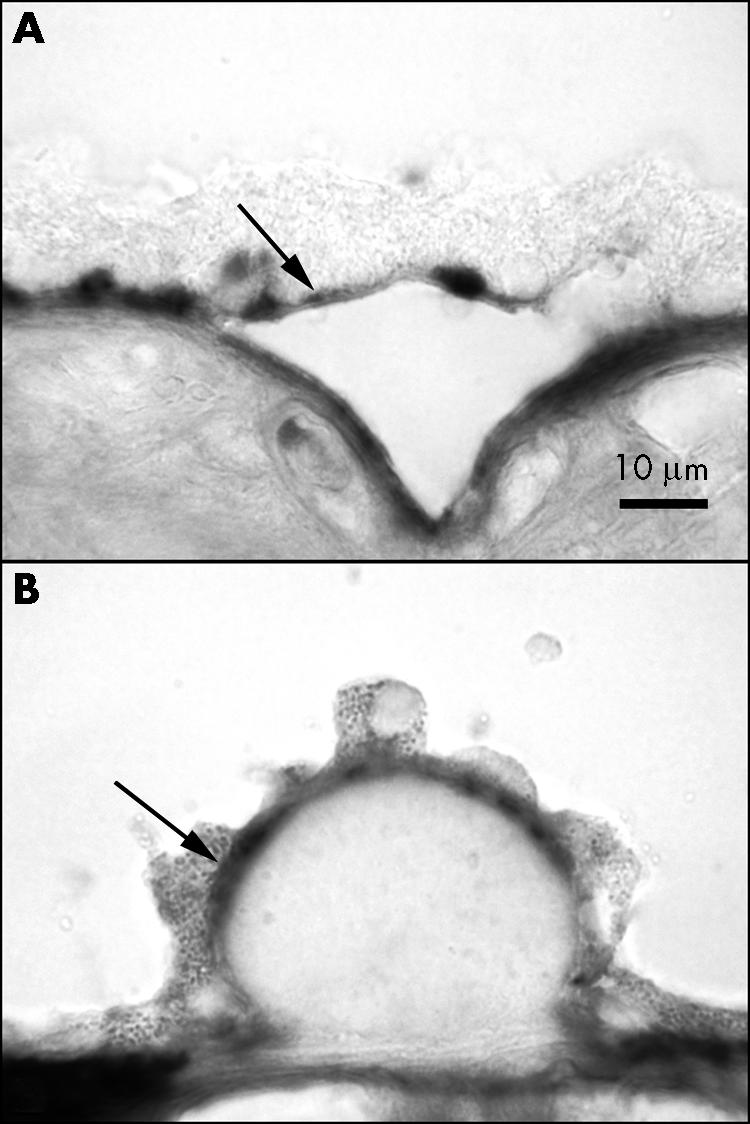

In aged subjects, TSP‐1 immunoreactivity was present in RPE cells (fig 2H and L). At higher magnification, it was apparent that the TSP‐1 immunoreactivity was present predominantly in the basal and basolateral portion of the RPE (fig 3) and the expression was heterogeneous in that it was present in some RPE and not in adjacent cells. When RPE had artefactually detached from Bruch's membrane (fig 3A) or were over drusen (fig 3B), the reaction product appeared to be associated predominantly with RPE basement membrane.

Figure 3 TSP‐1 immunoreactivity associated with RPE. In areas with artefactual detachment of RPE (A) (case 11) and hard drusen (B) (case 10), most RPE associated immunoreactivity appears to be associated with RPE basement membrane or basal lamina (arrow).

Geographic differences in TSP‐1 in far periphery versus equator in the normal aged control eyes and eyes with AMD

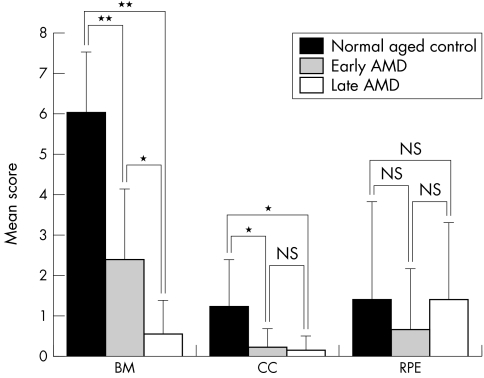

Negative to faint TSP‐1 staining was observed in some RPE, both in aged control eyes and AMD eyes (fig 2H and L) and there was no geographic difference in RPE between aged control eyes and AMD eyes. TSP‐1 immunoreactivity in choroid, especially in Bruch's membrane, was very weak or negative in the far periphery but remarkably higher at the equator in aged control eyes (fig 2F and H). TSP‐1 staining in choroid of eyes with AMD was less in the far periphery and the equatorial region than the normal aged control choroid (fig 2J and L); the difference was significant in score in both the far periphery (p = 0.00015) and at the equator (p = 0.013). Immunostaining of CD34 showed vascularised choroid in both regions in aged control and AMD eyes (fig 2E, G, I, and K). In normal aged control subjects and eyes with early AMD, the immunoreactivity scores for Bruch's membrane were lower in the far periphery than at the equator (fig 4A and B), whereas in late AMD, the scores were low at both the far periphery and the equator (mean scores <1; fig 4C).

Figure 4 Geographic difference in TSP‐1 expression in Bruch's membrane of normal control eyes (A), early AMD (B), and late AMD (C). Mean scores for TSP‐1 immunoreactivity in periphery, equator, and macula are represented in the graphs. (Significant differences compared to periphery by Wilcoxon signed rank test: *p<0.001 and **p<0.0001.)

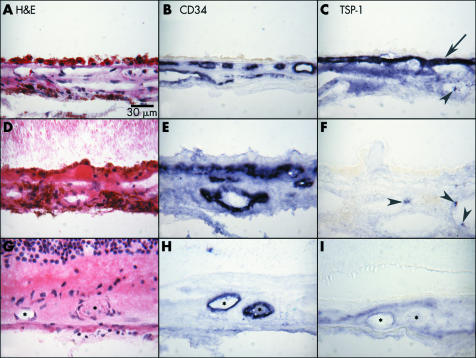

Expression of TSP‐1 in submacular choroid of normal aged eyes and eyes with AMD

In the submacular region of normal aged control eyes, TSP‐1 staining was intense in Bruch's membrane but moderate in choriocapillaris and adventitial cells of choroidal blood vessels (fig 5C). The normal structure and blood vessel distribution of aged choroid are shown in figures 5A and B. In contrast, eyes with early AMD (case 24) and late AMD (case 17) had negative to weak TSP‐1 expression in Bruch's membrane, choriocapillaris, and RPE layer (fig 5F and I). Five out of nine AMD subjects had Bruch's membrane scores less than 1 at the equator and six of nine AMD subjects had scores ⩽1 in the macula (fig 4B and C).

Figure 5 Immunolocalisation of TSP‐1 in macular choroid of a normal aged control (A–C; case 9), an early AMD subject (D–F; case 24), and late AMD with CNV (G–I; case 17). In the aged control eye (C), TSP‐1 immunoreactivity is intense especially in Bruch's membrane (arrow). In early AMD (F), no remarkable TSP‐1 immunoreactivity is observed except in platelets in the large choroidal vessels. In late AMD, TSP‐1 immunoreactivity is quite low in and around CNV (I). Haematoxylin and eosin staining shows morphological features of these choroids (A, D, G). CD34 immunostaining indicates choriocapillaris, large choroidal blood vessel, or viable CNV (B, E, H). Arrowheads indicate TSP‐1 positive platelets; asterisks indicate CNV.

Compared to aged controls (fig 5A), drusen and basal laminar deposits were observed under RPE in early AMD eyes and the choriocapillaris lumens appeared constricted and irregular (fig 5D and E). In the late AMD, CNV was observed under the photoreceptor layer (fig 5G and H). In the example of late AMD with geographic atrophy (case 17) shown in figure 5, weak TSP‐1 staining was observed in sub‐RPE CNV (fig 5H and I). The immunoreactivity scores for TSP‐1 in the macular region were significantly lower in Bruch's membrane and choriocapillaris in early and late AMD eyes compared with the normal aged control eyes. With increasing severity of AMD (early versus late AMD), Bruch's membrane and choriocapillaris scores declined significantly in the late AMD group. However, there was no significant difference in scores for the RPE between the groups (fig 6). On the other hand, although the mean scores were quite low (0.889) in choroidal stroma of normal aged group, there was a significant difference compared to late AMD group (p = 0.018) (data not shown).

Figure 6 Change in TSP‐1 expression in submacular region of normal control eyes and eyes with early and late AMD. Mean scores (SD) for TSP‐1 immunoreactivity in each structure is represented. (Significant differences by unpaired Student's t test: *p<0.001 and **p<0.0001.) (BM, Bruch's membrane, CC, choriocapillaris, RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.)

Several reports have shown the influence of diabetes on the expression of TSP‐1 in diabetic rats.25,26 We examined two AMD cases with diabetes mellitus (case 20 and 21) and found no remarkable differences in retina or choroid between subjects with AMD and diabetes compared with other AMD cases.

Expression of TSP‐1 in the disciform scar

In late AMD (case 21) having disciform scar (fig 7A) with a small CNV (fig 7A and B), there was intense but diffuse TSP‐1 immunoreactivity in the scar (fig 7C). At higher magnification, the disciform scar had both avascular (fig 7E) and vascularised areas (fig 7H). In the avascular area of the disciform scar, abundant migrating RPE cells were observed (fig 7D) along with intense TSP‐1 staining (fig 7F), whereas vascularised areas had few RPE (fig 7G) and weaker TSP‐1 staining (fig 7I). The mean TSP‐1 immunoreactivity score for CNV was 1 and the score for scars was 5 (p<0.0001).

Figure 7 Immunolocalisation of TSP‐1 in a disciform scar (case 21). The scar is shown at low magnification in (A–C), an avascular area of the disciform scar in (D–F), and an area with CNV in the disciform scar in (G–I). Around the disciform scar, the RPE layer and retinal photoreceptor layer are severely pathological (A). The vasculatures and distribution of TSP‐1 staining are shown in (B) and (C), respectively. In an avascular area of the disciform scar (E), abundant RPE cells are present (D), and intense TSP‐1 staining (F) is observed. In the vascularised area (H), no RPE (G), and weaker TSP‐1 staining is observed (I).

Discussion

This study demonstrated the relative levels and localisation of TSP‐1 in normal aged and AMD eyes. TSP‐1 was localised in RPE basal lamina, Bruch's membrane, choriocapillaris, and the walls of retinal and choroidal blood vessels in normal aged eyes. In eyes with AMD, TSP‐1 immunoreactivity was significantly decreased, especially in Bruch's membrane and choriocapillaris in the submacular region. Moreover, in the submacular region, TSP‐1 expression in choroidal stroma was significantly decreased in late AMD. Analysis of geographic differences demonstrated that TSP‐1 expression in the far periphery was significantly lower than at the equator and in the submacular regions in normal aged eyes and eyes with early AMD. In late AMD, TSP‐1 expression was extremely low not only in the far periphery, but also in the submacular region. The statistical significance of lower TSP‐1 in the periphery of aged versus young eyes could not be assessed because we had only one eye from a young subject. A previous study demonstrated TSP‐1 expression in the cytoplasm of RPE cells and in the some parts of Bruch's membrane in the normal human eye.17 In the current study, a variable TSP‐1 localisation was observed predominantly in the basal portion of RPE (fig 3), but TSP‐1 was most prominent in Bruch's membrane, choriocapillaris, and in the wall of large choroidal and retinal blood vessels in normal eyes. TSP‐1 localisation in the basement membrane, blood vessel wall, and some connective tissues has been described in various human tissues.27,28 TSP‐1 is considered a secreted protein that binds to basement membrane components like heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG). Therefore, in the normal eye, TSP‐1 localisation might be expected in basement membranes such as Bruch's membrane, RPE basement membrane, and blood vessel walls.

TSP‐1 immunoreactivity was always lower in the far periphery and this low level did not depend on age or pathological condition. Bruch's membrane is thinner in the far periphery than more centrally, so there may be fewer binding sites for TSP‐1. Since the density of RPE, a TSP‐1 producing cell, is lowest throughout life in the peripheral retina adjacent to the ora serrata,29 it is feasible that relative TSP‐1 levels may be dependent on the RPE cell density and/or pathological changes in the RPE.

Various factors, such as thickened Bruch's membrane, damage to RPE and surrounding tissue by oxidative stress, inflammation, and abnormal choroidal blood flow have been considered in the pathogenesis of AMD.30,31 In this study, with increased severity of AMD, expression of TSP‐1 decreased in Bruch's membrane and choriocapillaris but this was not true for RPE cells (fig 6). These data support the hypothesis that the angiogenesis balance described above may be altered in AMD by declining levels of TSP‐1. We recently observed no significant difference in relative VEGF immunoreactivity levels in choroid/RPE between aged subjects and subjects with AMD,4 suggesting that a decline in anti‐angiogenic agents like TSP‐1 may upset the balance that is normally present, and not an increase in angiogenic factors.

Impaired expression of TSP‐1 may permit CNV and TSP‐1 may increase during the scar formation, inhibiting the further expansion of CNV in disciform scar. In addition, many migrating RPE cells were observed in avascular areas of disciform scar surrounding infarcted CNV, whereas they were not observed in vascularised areas. Migrating RPE cells may also produce TSP‐1 (fig 7), which stimulates regression of CNV in scars. TSP‐1 is known to activate transforming growth factor β, a well known scar inducing and anti‐angiogenic factor. A recent report demonstrated that these proteins modulate each other's expression.32,33

Bruch's membrane has been considered as a physical as well as a biological barrier for CNV. Bruch's membrane is a stratified ECM complex, which includes type IV collagen, elastin, laminin, and HSPG.34,35 A recent report provides evidence that thickness of elastic lamina was significantly lower in Bruch's membrane in the macula of eyes with AMD compared with normal eyes, which suggests that the decreased thickness of Bruch's membrane in macula is associated with CNV progression.36 A thinner and probably more fragile Bruch's membrane with impaired expression of TSP‐1 may contribute to the progression of CNV in the submacular region.

In conclusion, the expression of TSP‐1 declines in the eyes with AMD compared to normal aged eyes. Our results suggest that TSP‐1 in Bruch's membrane and choroidal stroma may provide a biological barrier for CNV formation and progression. Impaired expression of TSP‐1 in AMD may permit CNV formation in AMD. The decrease in TSP‐1, in addition to PEDF4 and endostatin3 reported previously in macula of AMD subjects, certainly suggests that the Bruch's membrane in macula is vulnerable to CNV invasion.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant EY‐01765 (Wilmer), the RPB (Research to Prevent Blindness) (Wilmer), the Foundation Fighting Blindness (GL), and Overseas Research Scholarship, Fukuoka University, School of Medicine Alumni, Eboshikai (KU). The authors are grateful to the eye donors and their relatives for their generosity and Janet Sunness, MD, and Carol Applegate at the Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute (Baltimore, MD, USA) for helping us acquire eyes from subjects with geographic atrophy.

Abbreviations

AMD - age related macular degeneration

CNV - choroidal neovascularisation

ECM - extracellular matrix

HSPG - heparan sulfate proteoglycan

PEDF - pigment epithelium derived factor

RPE - retinal pigment epithelium

TSP‐1 - thrombospondin‐1

References

- 1.Klein R, Klein B E, Jensen S C.et al The five‐year incidence and progression of age‐related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology 19971047–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witmer A N, Vrensen G F, Van Noorden C J.et al Vascular endothelial growth factors and angiogenesis in eye disease. Prog Retin Eye Res 2003221–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhutto I A, Kim S Y, McLeod D S.et al Retinal and choroidal localization of collagen XVIII and the endostatin portion of collagen XVIII in aged human control and in age‐related macular degeneration subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004451544–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhutto I A, McLeod D S, Hasegawa T.et al Pigment epithelial‐derived factor (PEDF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in aged choroid and eyes with age related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2005, (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Sarks S H. Aging and degeneration in the macular region: a clinico‐pathological study. Br J Ophthalmol 197660324–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handa J T, Verzijl N, Matsunaga H.et al Increase in the advanced glycation end product pentosidine in Bruch's membrane with age. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 199940775–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guymer R, Luthert P, Bird A. Changes in Bruch's membrane and related structures with age. Prog Retin Eye Res 19991859–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green W R, McDonnell P J, Yeo J H. Pathologic features of senile macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 198592615–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spraul C, Grossniklaus H E. Characteristics of drusen and Bruch's membrane in postmortem eyes with age‐related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 1997115267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green W R, Enger C. Age‐related macular degeneration histopathologic studies. The 1992 Lorenz E. Zimmerman Lecture. Ophthalmology 19931001519–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curcio C, Millican C. Basal linear deposit and large drusen are specific for early age‐related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1999117329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baenziger N L, Brodie G N, Majerus P W. A thrombin‐sensitive protein of human platelet membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 197168240–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baenziger N L, Brodie G N, Majerus P W. Isolation and properties of a thrombin‐sensitive protein of human platelets. J Biol Chem 19722472723–2731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reed M J, Iruela‐Arispe L, O'Brien E R.et al Expression of thrombospondins by endothelial cells. Injury is correlated with TSP‐1. Am J Pathol 19951471068–1080. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaffe E A, Ruggiero J T, Falcone D J. Monocytes and macrophages synthesize and secrete thrombospondin. Blood 19856579–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raugi G J, Mumby S M, Abbott‐Brown D.et al Thrombospondin: synthesis and secretion by cells in culture. J Cell Biol 198295351–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyajima‐Uchida H, Hayashi H, Beppu R.et al Production and accumulation of thrombospondin‐1 in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200041561–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tolsma S S, Volpert O V, Good D J.et al Peptides derived from two separate domains of the matrix protein thrombospondin‐1 have anti‐angiogenic activity. J Cell Biol 1993122497–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iruela‐Arispe M L, Lombardo M, Krutzsch H C.et al Inhibition of angiogenesis by thrombospondin‐1 is mediated by 2 independent regions within the type 1 repeats. Circulation 19991001423–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawson D W, Pearce S F, Zhong R.et al CD36 mediates the In vitro inhibitory effects of thrombospondin‐1 on endothelial cells. J Cell Biol 1997138707–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jimenez B, Volpert O V, Crawford S E.et al Signals leading to apoptosis‐dependent inhibition of neovascularization by thrombospondin‐1. Nat Med 2000641–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uchida H, Hayashi H, Kuroki M.et al Vitamin A up‐regulates the expression of thrombospondin‐1 and pigment epithelium‐derived factor in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res 20058023–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lutty G A, Merges C, Threlkeld A B.et al Heterogeneity in localization of isoforms of TGF‐b in human retina, vitreous, and choroid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 199334477–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLeod D S, Lefer D J, Merges C.et al Enhanced expression of intracellular adhesion molecule‐1 and P‐selectin in the diabetic human retina and choroid. Am J Pathol 1995147642–653. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheibani N, Sorenson C M, Cornelius L A.et al Thrombospondin‐1, a natural inhibitor of angiogenesis, is present in vitreous and aqueous humor and is modulated by hyperglycemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000267257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stenina O I, Krukovets I, Wang K.et al Increased expression of thrombospondin‐1 in vessel wall of diabetic Zucker rat. Circulation 20031073209–3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wight T N, Raugi G J, Mumby S M.et al Light microscopic immunolocation of thrombospondin in human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem 198533295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arbeille B B, Fauvel‐Lafeve F M, Lemesle M B.et al Thrombospondin: a component of microfibrils in various tissues. J Histochem Cytochem 1991391367–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harman A M, Fleming P A, Hoskins R V.et al Development and aging of cell topography in the human retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1997382016–2026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roth F, Bindewald A, Holz F G. Key pathophysiologic pathways in age‐related macular disease. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2004242710–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zarbin M A. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of age‐related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 2004122598–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mimura Y, Ihn H, Jinnin M.et al Constitutive thrombospondin‐1 overexpression contributes to autocrine transforming growth factor‐beta signaling in cultured scleroderma fibroblasts. Am J Pathol 20051661451–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakagawa T, Li J H, Garcia G.et al TGF‐beta induces proangiogenic and antiangiogenic factors via parallel but distinct Smad pathways. Kidney Int 200466605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hewitt A T, Nakazawa K, Newsome D A. Analysis of newly synthesized Bruch's membrane proteoglycans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 198930478–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Das A, Frank R N, Zhang N L.et al Ultrastructural localization of extracellular matrix components in human retinal vessels and Bruch's membrane. Arch Ophthalmol 1990108421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chong N H, Keonin J, Luthert P J.et al Decreased thickness and integrity of the macular elastic layer of Bruch's membrane correspond to the distribution of lesions associated with age‐related macular degeneration. Am J Pathol 2005166241–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]