Abstract

Aim

To assess the longitudinal changes in the spherical equivalent (SE) refractive errors of children with accommodative esotropia as a function of the age when glasses were prescribed.

Methods

Refractive errors were followed longitudinally for 126 children with accommodative esotropia for a mean of 4.4 (SD 2.5) years. Cycloplegic refractions were performed using an autorefractor for older children and retinoscopy for younger children. The refractive data were analysed for three groups of children based on their age at the time spectacles were prescribed.

Results

The initial SE refractive error was age dependent (<2 years, 5.1 (1.9) D; 2–<4 years, 4.2 (1.9) D; 4–8 years, 3.8 (1.7) D). Children in all age groups had an initial increase in their SE refractive error, followed by a later decrease; however, the greatest decrease occurred in the patients in the oldest age group. The SE refractive error peaked 1 year after spectacles were prescribed for the children 4–8 years of age versus 6 years after spectacles were prescribed for the children less than 2 years of age.

Conclusion

Longitudinal changes in SE refractive error for children with accommodative esotropia vary as a function of their age when spectacle wear is initiated.

Keywords: emmetropisation, accommodative esotropia, spheroequivalent refractive error, amblyopia, autorefraction, children

Accommodative esotropia has its onset during childhood and is associated with varying degrees of hyperopia. The initial treatment is optical correction of the full hyperopic refractive error. Several studies have followed longitudinally the spherical equivalent (SE) refractive errors of children with accommodative esotropia.1,2,3 In most cases, there is an increase in the SE refractive error during the first 7 years of life, followed by a myopic shift extending into adulthood. Usually the myopic shift is not large enough to allow spectacle wear to be discontinued.

Animal models have demonstrated that wearing either plus or minus lenses can alter the normal process of emmetropisation in immature eyes. Lens induced changes in refractive errors are generally compensatory, with plus lenses inducing a hyperopic shift and minus lenses a myopic shift.4,5 Smith and Hung6 noted that fully correcting the hyperopic refractive errors of juvenile monkeys induced a hyperopic shift.

The goal of this study was to evaluate the longitudinal changes in the SE refractive errors of children with accommodative esotropia as a function of their age when they were prescribed spectacles. Unlike other longitudinal studies of children with accommodative esotropia, we studied the longitudinal changes in refractive errors as a function of age when spectacles were prescribed rather than chronological age alone.

Methods

After obtaining approval from the institutional review board, data were collected from a consecutive series of patients with accommodative esotropia. The patients were identified by creating a printout of all patients in a database coded with ICD‐9 378.35 (accommodative component in esotropia), who were examined by the author between 1998 and 2001. The charts were then reviewed retrospectively and patients with 0.75 dioptre or more of hyperopia and an esotropia that decreased by 10 prism dioptres or more when the patient wore their full hyperopic correction were considered for inclusion in the study. Also included were patients who had been treated by another ophthalmologist before being examined by the author provided that all the inclusion criteria were met and provided that the date they were prescribed glasses and the refractive correction prescribed could be ascertained from their medical record. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a neurological disorder, other ocular disorders associated with reduced visual acuity, visual acuity not correctable to 20/30 or better in at least one eye, spectacle use before the onset of their esotropia, or a follow up interval of less than 6 months. All patients who were examined prospectively between January 2002 and April 2004 who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were also included in the study. A general information data form was completed on each patient including the date of birth, the date of the first ocular examination, the date the esotropia was first noted, the date spectacles were prescribed, and the dates strabismus surgeries were performed. A visit data form was then completed to record each time the patient underwent a cycloplegic refraction using retinoscopy or autorefraction. Included on this data form was date of the visit, refractive error (sphere, cylinder, and axis), technique used to assess refractive error, best spectacle corrected visual acuity (BSCVA), power of the correction worn, angle of stereopsis, angle of esotropia with and without correction, and type of amblyopia treatment prescribed. All patients were then assigned a study ID number and the data forms were then faxed to a biostatistician for analysis.

When possible visual acuity was obtained using Snellen letters. In younger children, Allen letters and the HOTV test were used. Amblyopia was defined as an interocular difference in visual acuity of two lines or more. Ocular alignment was assessed using the simultaneous prism cover test in older children and the Krimsky or Hirschberg light reflex test in younger children. Cycloplegia was obtained with 1% cyclopentolate. Refractions were performed 30–60 minutes later after the patients were fully cyclopleged. Beginning in December 1997, a Nidek ARK‐700A (Nidek, Hiroishi, Japan) autorefractor was used to ascertain the refractive error of all cooperative children. The Nidek ARK 700A autorefractor has a red hot air balloon as a fixation target and eye tracking capabilities which make it possible to autorefract most children who are 3 years of age or older. Before 1997 and in uncooperative children, the refractive error was ascertained using retinoscopy with hand held lenses or a phoropter. Cycloplegic refractions were generally performed once each year. They were performed more often if there was a reduction in visual acuity or a deterioration in ocular alignment. Anisometropia was defined as an interocular difference in the SE refractive error ⩾1.5 D.

Spectacles were prescribed that corrected the entire cycloplegic refractive error when spectacle treatment was initiated. In older children with fully accommodative esotropia, an attempt was made to gradually reduce their hyperopic correction to the lowest power that would maintain orthotropia without causing asthenopia. No attempt was made to wean children with partially accommodative esotropia from spectacles correcting their cycloplegic refractive error. The full astigmatic refractive error was prescribed for patients at all ages. The SE refractive error was defined as the sum of the sphere and one half of the cylinder power. Cylinder powers were measured and recorded using plus nomenclature.

Only five patients had more than 10 years of follow up, so data were only analysed for the first 10 years of follow up. Two patients were excluded from the analysis because the date of onset of esotropia could not be ascertained. Stereopsis was assessed using the TNO test (Lanéris Ootech, Groenekan, Netherlands). The stereopsis measurement that was taken closest to the age of 6 years was chosen for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and graphs of the refractive error and cylinder power were produced for various time points after spectacles were prescribed. Follow‐up visits were categorised into time intervals for the first and second 6 month periods after spectacles were prescribed and annual intervals thereafter. If a patient had more than one follow up visit within an interval, the mean of the measurements in the interval was used.

The statistical analysis relating the longitudinal values of refractive error and cylinder power to the time after spectacles were prescribed and the age of the patient was done using a general linear mixed model.7 The general linear mixed models were estimated using Proc Mixed from the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) (SAS Institute, Inc, Carey, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 126 patients met the inclusion criteria for the study. The mean age of onset of the esotropia was 2.6 (1.8) years (range 0–8.0 years) and the mean age that spectacles were prescribed was 3.2 (1.7) years (range 0.3–8.2 years). The mean length of follow up was 4.4 (2.5) years (range 0.5–9.7 years). Sixteen (13%) of the patients received patching therapy, three (2%) received atropine penalisation, and two (2%) received both. At the last follow up examination, the BSCVA was 20/30 or better in 109 (90%) right eyes and 107 (88%) left eyes and the worst BSCVA was 20/50 in a right eye and 20/60 in a left eye. Stereopsis was assessed at a mean age of 6.7 (2.2) years. Ten (12%) patients had 15–60 seconds of arc of stereopsis and 15 (18%) had 120–480 seconds of arc. The remaining 58 patients (70%) only had gross stereopsis (<480 seconds of arc) or no stereopsis. High grade stereopsis (15%–60 seconds of arc) was found to correlate with an older age when the esotropia was noted (p = 0.008) and an older age when spectacles were prescribed (p = 0.0167). Thirty eight patients (30%) underwent one or more strabismus operations.

Change in spherical equivalent refractive error

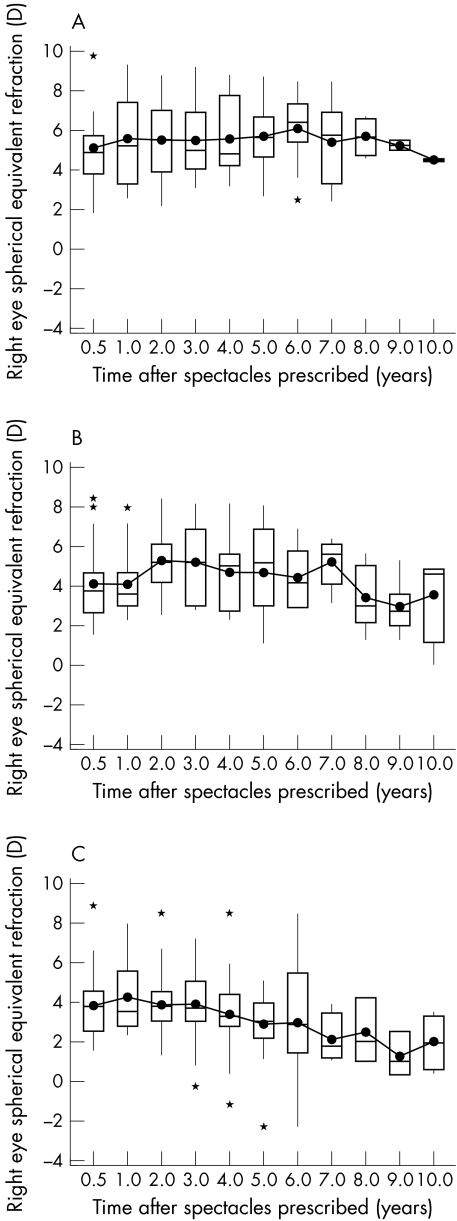

The mean initial SE refractive error was +4.44 (1.90) D for the right eyes and +4.53 (1.88) D for the left eyes. All of the patients were initially hyperopic in both eyes (range, +0.75 to +9.75 D). The mean last SE refractive error was +4.43 (2.07) D for the right eyes and +4.54 (2.04) D for the left eyes. One patient became myopic in both eyes and one patient was plano in both eyes. The remaining 124 patients remained hyperopic in both eyes. The mean SE refractive error for the right eyes increased for the first 3 years after spectacles were prescribed and then gradually decreased over the next 7 years (fig 1). The mean initial SE refractive error was greatest in children who were prescribed spectacles when they were less than 2 years of age (5.1 (1.9) D) and least in the children who were prescribed spectacles when 4–8 years of age (3.8 (1.7) D) (table 1). The SE refractive error peaked 1 year after spectacles were prescribed for the children 4–8 years of age versus 6 years after spectacles were prescribed for the children less than 2 years of age (fig 2 A–C). The children in the youngest age group had a higher SE refractive error for all follow up intervals. The SE refractive error remained relatively stable for the children in the youngest age group, whereas it decreased over the 10 year follow up period for the two older age groups. Similar changes in the SE refractive error were found when the autorefraction data were analysed separately (table 2). We also analysed the data from children with amblyopia (n = 19) and anisometropia (n = 11). Longitudinal changes in their SE refractive errors were not qualitatively different from the data from the non‐amblyopic and non‐anisometropic patients.

Figure 1 Spherical equivalent refractive error in right eye versus time after spectacles prescribed. There was a small increase in the mean SE refractive error peaking at 3 years. The box plots denote the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. A line is drawn horizonally through the box at the median. A dot is placed at the mean. Vertical lines extend from the edges of the box to the maximum and minimum values, unless these values extend more than 1.5× the interquartile range (75th percentile–25th percentile) beyond the edges of the box, in which cases the values beyond this point are marked by an asterisk.

Table 1 Spherical equivalent (SE) refractive error in right eye v time after spectacles were prescribed according to age when spectacles were prescribed.

| Time interval after spectacles prescribed (years) | Age when spectacles prescribed (years) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <2 | 2–<4 | 4–8 | |||||||

| SE refraction in right eye (D) | SE refraction in right eye (D) | SE refraction in right eye (D) | |||||||

| No | Mean | SD | No | Mean | SD | No | Mean | SD | |

| <0.5 | 14 | 5.1 | 1.9 | 35 | 4.2 | 1.9 | 28 | 3.8 | 1.7 |

| 0.5–1 | 8 | 5.5 | 2.3 | 20 | 4.2 | 1.6 | 17 | 4.3 | 1.8 |

| 1–2 | 25 | 5.5 | 2.0 | 28 | 5.2 | 1.7 | 30 | 4.0 | 1.5 |

| 2–3 | 27 | 5.6 | 1.7 | 21 | 5.1 | 1.8 | 25 | 3.9 | 1.7 |

| 3–4 | 22 | 5.5 | 1.9 | 24 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 22 | 3.3 | 1.9 |

| 4–5 | 17 | 5.7 | 1.7 | 11 | 4.7 | 2.2 | 16 | 2.7 | 1.7 |

| 5–6 | 12 | 6.0 | 1.7 | 13 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 7 | 3.0 | 3.4 |

| 6–7 | 8 | 5.4 | 2.1 | 4 | 5.0 | 1.3 | 4 | 2.1 | 1.3 |

| 7–8 | 4 | 5.7 | 0.9 | 6 | 3.4 | 1.6 | 3 | 2.4 | 1.7 |

| 8–9 | 4 | 5.2 | 0.3 | 6 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 3 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| 9–10 | 2 | 4.4 | 0.1 | 4 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 4 | 1.9 | 1.4 |

Figure 2 Spherical equivalent refractive error versus time after spectacles prescribed for children prescribed spectacles when < 2 years of age (A), 2 to < 4 years of age (B), and 4–8 years of age (C). The mean SE refractive error was relatively stable for the children in A and B, but decreased over time for the children in (C).

Table 2 Spheroequivlaent refraction in right eye v time after spectacles were prescribed: all refractions v autorefractions only.

| Time interval after spectacles prescribed (years) | Spheroequivalent in right eye | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Autorefractions only | |||||

| No | Mean | SD | No | Mean | SD | |

| <0.5 | 77 | 4.2 | 1.9 | 31 | 4.1 | 1.7 |

| 0.5–1 | 46 | 4.5 | 1.8 | 23 | 4.3 | 1.4 |

| 1–2 | 83 | 4.8 | 1.8 | 49 | 4.7 | 1.6 |

| 2–3 | 73 | 4.9 | 1.8 | 49 | 4.8 | 1.9 |

| 3–4 | 68 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 48 | 4.3 | 1.9 |

| 4–5 | 44 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 37 | 4.5 | 2.2 |

| 5–6 | 32 | 4.6 | 2.4 | 26 | 4.6 | 2.4 |

| 6–7 | 17 | 4.6 | 2.2 | 18 | 4.3 | 2.2 |

| 7–8 | 13 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 10 | 3.9 | 1.7 |

| 8–9 | 13 | 3.2 | 1.8 | 12 | 3.4 | 1.8 |

| 9–10 | 10 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 9 | 3.4 | 1.7 |

Linear mixed model

To evaluate the statistical significance of the effect of age when spectacles were prescribed and time after spectacles were prescribed on the change in the mean SE refractive error, a linear mixed model was employed (table 3). The final model included a linear term for age, a linear and quadratic term for time after spectacles were prescribed, and an interaction term for age and time. The quadratic term for time after spectacles were prescribed (p<0.0001) and the interaction of age and time after spectacles were prescribed (p<0.0001) were both highly significant. Following the hierarchical principle, the linear terms for both time after spectacles were prescribed (p<0.0001) and age (p = 0.03) were also included in the model. The model suggested that there was a significant effect of age and time after spectacles were prescribed on the SE refractive error. The SE refractive error changed in a non‐linear manner with time according to the age of the child at the time spectacles were prescribed. These effects can be readily viewed in a graph of the model (fig 3). The graph of the model shows that the mean SE refractive error versus time after spectacles were prescribed according to the age when spectacles were prescribed. The graph illustrates that the SE refractive error did not peak for several years after spectacles were prescribed for the youngest patients, whereas for children who were prescribed spectacles at an older age there was almost an immediate decline in their SE refractive error.

Table 3 Regression model for mean spherical equivalent refractive error v time after spectacles were prescribed and age when spectacles were prescribed.

| Model term | Estimate (standard error) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept (β1) | 5.06 (0.35) | <0.0001 |

| Age (β2) | −0.21 (0.01) | 0.0318 |

| Time (β3) | 0.45 (0.06) | <0.0001 |

| Age × Time (β4) | −0.07 (0.01) | <0.0001 |

| Time2 (β5) | −0.04 (0.01) | <0.0001 |

Mean spherical equivalent refraction = β1 + β2 age + (β3 + β4 age) time + β5 time2.

Figure 3 Regression model of the mean SE refractive error versus time after spectacles prescribed for children prescribed glasses at ages 0.5 years to 6 years. The initial mean SE refractive error was higher the younger the age that spectacles were prescribed. The differences increased over time since the children prescribed spectacles when 0.5 year and 1.0 year of age had a small increase in their SE refractive error, whereas the other children had a progressive decrease in their SE refractive error which was greatest for the children prescribed glasses when 6 years of age.

Discussion

Accurately assessing the refractive errors of young children is challenging owing to their inability to give subjective responses and the difficulty of having children maintain fixation on a distant target. While retinoscopy with either hand held lenses or a phoropter has traditionally been used to determine the refractive errors of young children, autoretraction is gradually supplanting retinoscopy as a result of its greater accuracy.7,8 Unfortunately, it is quite difficult to autorefract most children 2 years of age or younger using the Nidek ARK‐700A autorefractor. This shortcoming limited the autorefraction data available for the youngest age group.

We found that the SE refractive error peaked 3 years after spectacles were prescribed and gradually decreased thereafter. Repka and colleagues9 and Raab2,10 have reported that the SE refractive error increases in children with accommodative esotropia until they are 7 years of age and then decreases thereafter. However, we found that the longitudinal change in the SE refractive error varied as a function of the age of the child when spectacles were prescribed. For children who were less than 2 years of age when spectacles were prescribed, the SE refractive error peaked 6 years after they were prescribed spectacles. In contrast, hyperopia peaked more quickly for children who were prescribed glasses at a later age. Children in the oldest age group also experienced a greater myopic shift over time. The effect of age on the change in SE refractive error versus time is shown in figure 3. The higher baseline SE refractive error for the children in the younger age group was probably a major factor accounting for the earlier age of onset of accommodative esotropia for these children. The reduced myopic shift among the patients in the youngest age group may have been because of a greater susceptibility to the effects of plus lens wear on their more rapidly growing eyes. Alternatively, it may reflect an intrinsic tendency for eyes with high hyperopia to undergo less emmetropisation. A final possibility is that the children in the younger age groups were not as old when last examined as the patients in the oldest age group and therefore they may not have experienced their full myopic shift.

While wearing plus lenses has been shown to consistently interfere with emmetropisation using various animal models, the effect of wearing plus lenses on the emmetropisation of children is less certain. Ingram11 randomised a group of infants with 4D or more of hyperopia to no treatment or to a partial correction with spectacles. After a 3 year follow up, more of the children randomised to spectacle wear who consistently wore their spectacles retained 3.5D or more of hyperopia. Richardson (Richardson S, AAPOS Meeting, 2004, Abstract) randomised a group of children with anisometropic amblyopia to spectacle correction or no treatment for 1 year. Spectacle correction impeded emmetropisation in the normally sighted eyes, but not in the amblyopic eyes. The most pronounced effect occurred in children with 3D or more of baseline hyperopia. These results would suggest that amblyopic eyes may be less sensitive to the effects of spectacle wear on emmetropisation than normally sighted eyes. We had only a small number of amblyopic eyes in our study, but we did not find a qualitative difference in the longitudinal changes in the SE refractive errors of the amblyopic eyes. In a small prospective study of children with high hyperopia and a family history of strabismus, Aurell and Norsell12 reported that the children who developed accommodative esotropia and were treated with spectacles maintained or increased their hyperopia, whereas the children who did not develop accommodative esotropia and who were not treated with spectacles lost most of their hyperopia by the time they were 4 years of age. In contrast, Atkinson and colleagues13 reported that spectacle wear had only a small, transient effect on emmetropisation for infants with at least one meridian of hyperopia ⩾+3.5 D who were randomised to a partial spectacle correction of their hyperopia.

This study has a number of limitations. Firstly, the study was retrospective, resulting in incomplete data for some patients. Secondly, retinoscopic refractions and autorefractions were combined for some of the data analyses. It would have been preferable if autorefraction data alone could have been used; however, this requirement would have significantly reduced both the sample size and the length of follow up. Thirdly, it would have been instructive to have studied a control group of age matched children who were not treated with spectacles. The most appropriate control group would be age matched children with accommodative esotropia who were not treated with spectacles; however, it would be unethical to withhold spectacle treatment from these children. Alternatively, age matched children without accommodative esotropia, but who had similar refractive errors could serve as a control group. However, it would be difficult to identify a large sample size of patients with these characteristics and their refractive development may differ from children with accommodative esotropia independent of spectacle wear. Finally, a longer follow up interval would have been preferable. The effects we noted may have been more or less pronounced had the follow up been longer.

While spectacle wear has been proved to be an effective means of restoring ocular alignment, averting amblyopia, and maintaining stereopsis for many children with accommodative esotropia,14,15 it may also interfer with emmetropisation. Further studies will hopefully elucidate the optimal means to optically correct children with accommodative esotropia to minimise the effect of spectacle wear on emmetropisation.16,17

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health, Departmental Core Grant EY 06360 and Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc.

Abbreviations

BSCVA - best spectacle corrected visual acuity

SE - spherical equivalent

References

- 1.Swan K C. Accommodative esotropia long range follow‐up. Ophthalmology 1983901141–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raab E L. Etiologic factors in accommodative esodeviation. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 198280657–694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulvihill A, MacCann A, Flitcroft I.et al Outcome in refractive accommodative esotropia. Br J Ophthalmol 200084746–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaeffel F, Glasser A, Howland H C. Accommodation, refractive error and eye growth in chicks. Vis Res 198828639–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hung L ‐ F, Crawford M L J, Smith E L. Spectacle lenses alter eye growth and the refractive status of young monkeys. Nat Med 19951761–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith EL I I I, Hung L ‐ F. The role of optical defocus in regulating refractive development in infant monkeys. Vis Res 1999391415–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verbeke G, Molenberghs G.Linear mixed models for longitudinal data, New York: Springer‐Verlag, 2000

- 8.Dobson V, Miller J M, Harvey E M.et al Amblyopia in astigmatic preschool children. Vis Res 2003431081–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Repka M X, Wellish K, Wisnicki H J.et al Changes in the refractive error of 94 spectacle‐treated patients with acquired accommodative esotropia. Binocular Vis 1989415–21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raab E L, Spierer A. Persisting accommodative esotropia. Arch Ophthalmol 19861041777–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ingram R M, Arnold P E, Dally S.et al Emmetropisation, squint, and reduced visual acuity after treatment. Br J Ophthalmol 199175414–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aurell E, Norsell K. A longitudinal study of children with a family history of strabismus: factors determining the incidence of strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol 199074589–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atkinson J, Anker S, Bobier W.et al Normal emmetropization in infants with spectacle correction for hyperopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000413726–3731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pratt‐Johnson J A, Tillson G.Management of strabismus and amblyopia. A practical guide. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers Inc, 1994106–122.

- 15.Lambert S R. Accommodative esotropia. Ophthalmol Clinics of NA 200114425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert S R, Lynn M, Sramek J.et al Clinical features predictive of successfully weaning from spectacles those children with accommodative esotropia. J AAPOS 200377–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutcheson K S, Ellish N J, Lambert S R. Weaning children with accommodative esotropia out of spectacles: a pilot study. Br J Ophthalmol 2003874–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]