Abstract

This review explores the role of health promotion in the prevention of avoidable blindness in developing countries. Using examples from eye health and other health topics from developing countries, the review demonstrates that effective eye health promotion involves a combination of three components: health education directed at behaviour change to increase adoption of prevention behaviours and uptake of services; improvements in health services such as the strengthening of patient education and increased accessibility and acceptability; and advocacy for improved political support for blindness prevention policies. Current eye health promotion activities can benefit by drawing on experiences gained by health promotion activities in other health topics especially on the use of social research and behavioural models to understand factors determining health decision making and the appropriate choice of methods and settings. The challenge ahead is to put into practice what we know does work. An expansion of advocacy—the third and most undeveloped component of health promotion—is essential to convince governments to channel increased resources to eye health promotion and the goals of Vision 2020.

Keywords: eye health, blindness, developing countries

Blindness is one of the most tragic—yet often avoidable—disabilities in the developing world.1 Actions by individuals, families and communities, as well as eye care professionals, are vital to achieving the ambitious target of “Vision 2020: the right to sight,” which aims to prevent 100 million cases of blindness by the year 2020.2 In this review, we will selectively draw from published research on eye health developing countries to draw out general principles that could be applied to planning eye health promotion interventions.

The importance of human behaviour

The prevention of blindness involves addressing the role of human behaviour in eye health. In some cases this might involve encouraging the adoption of eye health promoting behaviours and in other cases the discouragement of behaviours that damage eye health. The role of human behaviour and the scope for prevention depends on the specific disease: for conditions such as trachoma, eye injuries, vitamin A deficiency, and sexually transmitted diseases there is considerable scope for primary prevention. Secondary prevention involving recognition of symptoms and early presentation for treatment is appropriate for other conditions—for example, cataract, trichiasis, eye infections, and leprosy. Even when the intervention is mass treatment (for example, for the control of onchocerciasis), willingness by communities to take up these services is key in determining the success of the programme.

Eye health promotion

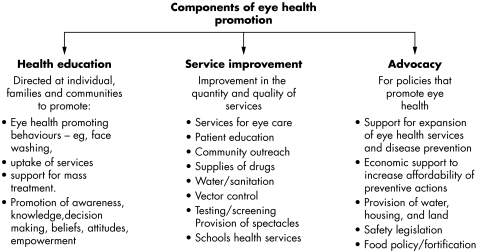

The concept of health promotion was first elaborated in 1986 in the Ottawa Charter which set out five areas of activity3 which can be grouped4 into three areas of action: health education, reorientation, and advocacy (fig 1). In this review the focus will be on the health education component, highlighting the role of reorientation of health services and advocacy where relevant.

Figure 1 Components of eye health promotion.

Health education

Health education to promote the adoption of eye health promoting behaviours and increase uptake of eye care services provides the backbone of health promotion. Changing long standing behaviours that might be deeply rooted in culture is never easy. However, well planned educational programmes can be effective provided two critical requirements are fulfilled: the underlying influences on behaviour are addressed, and appropriate methods, target groups, and settings are selected.

Understanding influences on behaviour

Qualitative research methods provide useful insights into reasons for use and non‐use of eye health services. Barriers to the uptake of cataract services from patients' perspectives can include one or more of the following: acceptance of impaired sight as an inevitable consequence of old age, fear of the operation, contact with individuals who have had bad experiences, lack of encouragement from the family, lack of knowledge concerning where surgery is provided, distance from the service, lack of a person to accompany the patient to hospital, poor state of hospitals, long waiting lists, and cost. Recent studies in Malawi, Nigeria, Gambia, and Nepal show that cost is the most important barrier.5,6,7,8,9 Barriers vary from location to location, and a study from India suggests that barriers can also change over time.10 Barriers similar to those outlined above for cataract also apply to trichiasis surgery,11,12,13 and, in northern Nigeria, low perceived risk and lack of appreciation of the benefits of surgery emerged as important barriers.13 The impact on uptake of developing affordable community based services has been shown in the Gambia.14 Lack of confidence in the service being provided was identified as an important factor in a study of glaucoma in Togo, west Africa. In a survey of 767 people who lived in and around the capital city, Lomé, almost two thirds of sample who were aware of glaucoma (25%) were not confident of the capabilities of doctors to treat the disease.15 Stigma attached to some diseases (for example, leprosy) can be a deterrent to coming forward for treatment with the result that ocular complications may be identified at a late stage. Here, the health promotion strategy is to address the issue of stigma and other barriers to early presentation for treatment in the general public and train leprosy healthcare workers in the recognition of ocular complications and lid surgery for lagophthalmos.

Many communities have traditional beliefs on the nature, cause, and prevention of blinding conditions. For example, an ethnographic study of women in Nepal found that night blindness (which is common in vitamin A deficiency) was recognised, local names existed, and the condition was considered serious.16 The importance of traditional beliefs has also been highlighted in studies of onchocerciasis in Nigeria17,18and Uganda.19 The Nigerian study identified local terms for skin rashes and nodules, and an impressive knowledge of the daily and seasonal distribution of the Simulium fly that transmits the disease. However, only 3% of the 1012 people interviewed related the clinical manifestations of onchocerciasis to Simulium bites—their explanations of the disease included exposure to sun (19%), hereditary (18%), cola nut (15%), and witchcraft (3%).18 In a very different setting among Mayan Indians in Guatemala, a survey before Mectizan (ivermectin, MSD) distribution established that, although there was a local name for onchocerciasis (“la filarial”), few knew it was caused by a worm and only half knew it was transmitted by insects.20 There was also substantial opposition to the proposed plan for Mectizan distribution and the authors suggested that this was because health education failed to explain that Mectizan was to prevent blindness, and did not address concerns about possible side effects. Interviews with participants in early Mectizan trials in Sierra Leone and Nigeria found that passing intestinal parasites caused alarm.21 However, another study in Nigeria found this same phenomenon was taken by communities to be proof of the effectiveness of Mectizan.22

Sustainable programmes may require some financial input from communities. A series of studies in Enugu State, Nigeria provided the encouraging information that a very high proportion of the communities stated their preparedness to contribute towards the costs of Mectizan distribution.23 Willingness to pay is not an easy topic to study as it depends not only on income but also on perceptions of the benefits of taking action, the value placed on eye health, and competing priorities for limited resources.

Choice of setting for health education

Many influences on behaviour including culture, economics, power, and tradition operate at the community level. A community based programme is one which works within a geographically defined area, takes into account influences that operate at community level, and seeks to involve community members in the decision making process and in implementation.24 The ideal situation is that the community decides its own health priorities, as well as the solutions, and how these will be resourced, implemented, monitored, and evaluated. Unfortunately, this ideal is not always realised, and the term “community participation” has been loosely applied to a range of approaches from ones with full involvement of communities to “top down” programmes where all decisions are made externally.25,26,27 Working with communities can be challenging: field workers need to be sensitive to the communities' needs and dynamics, and have patience and skills for a two way process of communication, to build consensus, resolve conflicts, and develop capacity.

An early study in the late 1970s in Gazankulu, South Africa, found that community based approaches using volunteers and community groups could have some impact on eye health knowledge and on the incidence of trachoma.28 Indeed, one of the strengths of this pioneering study is that it shows that eye health can be a starting point for involving communities in addressing a wide range of health and social concerns.29,30 In Tanzania, a community based approach to promotion of face washing used non‐formal adult education methods, drama, and the training of locally recruited facilitators to improve the cleanliness of children's faces.31

The use of volunteers is an important component of the community directed distribution of Mectizan that is now central to the Africa Programme for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC) which operates in west and central Africa. This is a highly successful programme that, in 2002, treated over 32 million people with an annual dose of Mectizan. The success of community directed treatment is such that this approach is now being used in filariasis control, for distributing bed nets and vitamin A, and distributors are also being trained to identify individuals who are cataract blind.32

Community based approaches build on local resources that include traditional healers—many of whom treat eye complaints.33,34,35 In Malawi, traditional healers were invited to attend a course in primary eye care specifically designed for them, which included observing cataract surgery. However, despite this, delays in presentation persisted,36 demonstrating the need for health promotion in the communities the traditional healers come from. A project to control vitamin A deficiency among 830 families in coastal Bangladesh evaluated an 18 month intervention which used group meetings in schools, mosques, and community settings supplemented with posters, leaflets, and a calendar. Evaluation showed increased knowledge about vitamin A rich foods, increased cultivation of vegetables, and a reduction in the prevalence of night blindness.37 Churches, mosques, and other faith based organisations are another setting for health education activities.

Community based programmes often use volunteer “community health workers,” also called peer educators, who were a key element of primary healthcare strategies implemented by many countries. Evaluations of these early experiments in using community volunteers showed the importance of realistic expectations, careful selection, appropriate training, monitoring, supervision, and support.38,39 The success of APOC is probably the result of the focused nature of the programme and the strong support provided to the community volunteers.

A strength of community based approaches is the opportunity for multisectoral strategies in which health education is supported by other interventions such as appropriate technology, agriculture, and income generation. This combination of strategies formed the basis of a series of innovative and highly successful pilot programmes coordinated by the International Centre for Research which worked with women to control vitamin A deficiency. Activities included introduction of a vitamin A rich variety of sweet potato in Kenya, solar drying of vitamin A rich foods in Tanzania, and seed distribution/education on cultivation and food preparation for women in Ethiopia.40,41,42,43

Schools are another setting that affords enormous potential for blindness prevention programmes, and the obvious benefits of good vision on learning might be expected to act as a powerful motivation for parents, teachers, and children to support blindness prevention activities. One approach is for teams of health educators to visit schools and run health education sessions. This approach was shown to result in improved knowledge of onchocerciasis in Nigeria44 and trachoma in Ethiopia.45 However, a more sustainable approach is to train teachers, which is the approach used in the vision testing programme in India46,47,48 and a pilot project in Nigeria.49 A comprehensive school based approach should have three components: firstly, health education using activity based methods such as those pioneered by Child‐to‐Child and others50,51,52; secondly, a health promoting school environment which includes provision of water and sanitation, safe risk free play facilities and school gardens; and, thirdly, school health services involving health workers, teachers, and children in screening children for refractive errors, provision of spectacles, and management of simple eye health problems.

The use of health services as settings for eye health promotion is discussed later in the section on service improvement. A notable gap in the literature is reports of health promotion in the workplace setting to prevent eye injuries.

Methods that can be used

The two most important health education methods are mass media and face to face communication, either separately or together. Mass media have the potential to reach large numbers at a low cost per person reached. This was recently illustrated by a project in India which inserted an E chart and instructions on use into four daily newspapers. A telephone survey of 603 people after one advertisement found that, of the 125 people sampled who subscribed to that newspaper, 43 stated that they used the card to test their vision. At US$5500, the initial cost was high; however, the large circulation and resulting low cost per newspaper of $0.002 shows the potential of mass media to reach large numbers of people very cheaply.53 A limitation of newspapers is that they only reach the literate, newspaper reading section of society, but they are particularly useful if the aim is reach professional and middle class groups, which might be important for advocacy. The relative importance of radio and television varies from region to region. It is thus important to find out what media are available and who accesses them, and base the choice of media on the local pattern of use.

Health education through mass media can be delivered in a range of formats. Some may require payment (for example, advertisements, jingles, spot announcements), while others may be free (for example, news bulletins, documentaries, and dramas). A recent development is the use of “entertainment education,” in which health education is incorporated within drama and music. An example of this is the trachoma media campaigns implemented between 2001 and 2003 by the BBC World Service Trust in Tanzania, Ghana, Ethiopia, Nepal, and Nigeria. The mix of media used varied from country to country and included radio, print and community media, and video vans. The radio programmes include spots, dramas, and songs. Print media included flip charts, posters, board games, comic books, and playing cards. The programme was evaluated by interviews carried out before and after the campaign, and in Nepal this was supplemented by observational studies. An internal report (personal communication from Liz Frost of BBC World Service Trust) indicates that these campaigns achieved a high level of coverage of the radio listening public and recall of messages, and in Nepal the programme had some impact on self reported hygiene practices (including face washing). Hopefully, details of this most interesting programme will be published, which will allow a more detailed assessment of the impact achieved and lessons learnt.

A key element of effective mass media is initial research and testing of programmes before broadcast to ensure that messages are simple, relevant, acceptable, attract attention, and are understood.

It is generally accepted that mass media are particularly appropriate when the behaviour changes to be promoted are simple and there are no significant barriers to the community taking action. With more difficult behaviours, especially those that are underpinned by strong cultural beliefs, mass media need to be supplemented by more intensive community based approaches. Face to face discussions might be slower and more labour intensive, but they provide opportunities for direct engagement and participation of individual communities.

Social marketing uses mass media in combination with face to face education to promote the uptake of specific practices. The Academy of Educational Development in Washington has produced a set of case studies of vitamin A programmes, which combine mass media with face to face approaches: in Niger, radio and community drama groups were used to promote specific foods; in the Philippines radio, television, and printed media were used to promote five vitamin A rich foods; in Indonesia social marketing promoted vitamin A capsules.54 Another vitamin A programme supported by the International Centre for Research on Women built on an existing social marketing programme in Thailand and trained local women leaders in problem solving approaches to nutrition education. Their work was supported by the mobilisation of schools and the use of community public address systems and billboards and achieved significant increases of reported vitamin A consumption in all age groups, especially that of 2–5 year olds.55

Service improvement

Health education should take place alongside improvement in services. Improvements should address locally identified barriers, which might include quality of clinical care as well as all the other non‐clinical aspects of care—for example, timing of clinics and operating sessions; ensuring men and women have separate waiting areas; providing culturally acceptable food and prayer areas; ensuring a clean environment.

There is a need to improve the quality of information provided to patients to promote adherence to treatment regimes and follow up, to increase awareness of possible side effects and action needed to prevent recurrence. Implementing patient education in resource poor settings with crowded clinics and shortages of health workers is challenging. For example, a clinic based health education programme in the Gambia was found to have a disappointing impact on levels of eye infection.56 Glaucoma involves explaining a complex health problem and the need to adhere to a regime of self administered eye drops, or to accept surgery. Evaluation of a clinic based educational programme among 50 glaucoma patients in Brazil57 showed a significant improvement in all steps of eye drop instillation but was not able to show any improvement in knowledge of glaucoma, the concept of intraocular pressure, nor the purpose and importance of medication. Successful patient education may involve a range of approaches including teaching in groups, using videos in waiting areas,58 training lay people as counsellor/peer educators,59,60 involving other family members, training clinic staff to give clear and relevant advice supported with leaflets or charts.

Advocacy

Advocacy includes all activities designed to raise awareness of the importance of blindness prevention among policy makers and planners, to increase resources for blindness prevention, and for the integration of blindness prevention into other programmes. Advocacy can also lead to enactment and enforcement of laws that place on a legal footing the obligations of governments to ensure “the right to sight.” Advocacy can take place at every level from international, national, and local level. The most notably success for advocacy at the international level has been the endorsement of Vision 2020 by the World Health Assembly in May 2004 in which resolution WHA56.26 was adopted by member states.61

At the national and district level effective advocacy involves the mass media to gain public support, meetings with decision makers, and working through professional associations. An important objective for advocacy is to raise public awareness of the need for channelling public resources into prevention of blindness. The need for such action was recently demonstrated in surveys of urban populations in Andhra Pradesh State, India, and Togo that found low levels of awareness and knowledge of eye health15,62—a finding that would probably apply to many developing countries. Handbooks setting out advocacy methods have been prepared for polio,63 tuberculosis,64 and rights for sexual and reproductive health65; they contain many valuable insights that could be adapted to raising the profile of blindness issues.

General remarks

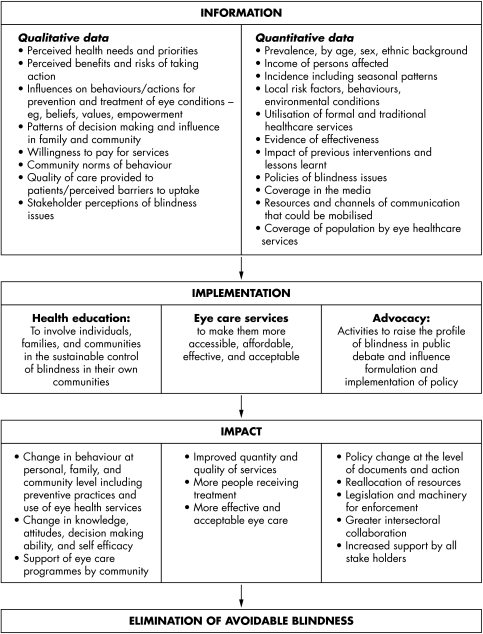

Health promotion, to be successful, must be built on a detailed understanding of the health topic and the intended audience. The vital contribution qualitative and quantitative data make to planning a health promotion strategy is shown in figure 2, as each community poses its own particular challenges and opportunities for creative solutions. Information from research about what an intended audience thinks, knows, and does about a particular health concern leads on to the development of the health education strategy, including the setting and nature of the intervention. Materials need to be developed and pilot tested, to ensure that the messages are correctly interpreted and understood.

Figure 2 Information needs for implementation and evaluation of eye health promotion.

Evaluation is essential to the expansion of eye health promotion. Evaluation should provide the information and feedback to make improvements in future activities. While the ultimate goal is improved eye health, it is useful to incorporate intermediate indicators, such as increased awareness, behaviour change, skills, self efficacy, coverage and quality of services, and adoption of specific policies.

Many of the principles of effective health promotion brought out in this paper have emerged from evaluations in the Leeds Health Education Database developed by one of the authors (JH) of health promotion interventions in developing countries,66,67 which has been posted on the internet (www.hubley.co.uk). While there is now a good range of evaluated examples for many health topics, the numbers of published interventions dealing specifically with eye health promotion are disappointingly small. We encountered notable gaps, such as the absence of published evaluations that consider the role of health promotion for major blinding conditions such as cataract, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and trauma in developing countries. We are aware of much relevant work that is reported informally at meetings and in newsletters but which does not get written up in peer reviewed journals. An important challenge is to document these unpublished experiences so the research base is open to scrutiny, and so that lessons learned can be incorporated into the evidence base for eye health promotion.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Paul Courtright for helpful comments on early versions of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya'ale D.et al Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull World Health Organ 200482844–851. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnikoff S, Pararajasegaram R. Blindness prevention programmes: past, present, and future. Bull World Health Organ 200179222–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Orgainzation Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. An International Conference on Health Promotion. November 17–21. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe 1986

- 4.Hubley J.Communicating health—an action guide to health education and health promotion. 2nd ed. Oxford: Macmillan, 2004

- 5.Courtright P, Kanjaloti S, Lewallen S. Barriers to acceptance of cataract surgery among patients presenting to district hospitals in rural Malawi. Trop Geogr Med 19954715–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson J G, Goode Sen V, Faal H. Barriers to the uptake of cataract surgery. Trop Doct 199828218–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewallen S, Courtright P. Recognising and reducing barriers to cataract surgery. Commun Eye Health 20001320–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabiu M M. Cataract blindness and barriers to uptake of cataract surgery in a rural community of northern Nigeria. Br J Ophthalmol 200185776–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shrestha M K, Thakur J, Gurung C K.et al Willingness to pay for cataract surgery in Kathmandu valley. Br J Ophthalmol 200488319–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaidyanathan K, Limburg H, Foster A.et al Changing trends in barriers to cataract surgery in India. Bull World Health Organ 199977104–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West S, Lynch M, Munoz B.et al Predicting surgical compliance in a cohort of women with trichiasis. Int Ophthalmol 199418105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowman R J, Faal H, Jatta B.et al Longitudinal study of trachomatous trichiasis in the Gambia: barriers to acceptance of surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200243936–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabiu M M, Abiose A. Magnitude of trachoma and barriers to uptake of lid surgery in a rural community of northern Nigeria. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 20018181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowman R J, Soma O S, Alexander N.et al Should trichiasis surgery be offered in the village? A community randomised trial of village vs health centre‐based surgery. Trop Med Int Health 20005528–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balo P K, Serouis G, Banla M.et al [Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding glaucoma in the urban and suburban population of Lome (Togo)]. Sante 200414187–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christian P, Bentley M, Pradhan R.et al An ethnographic study of night blindness “ratauni” among women in the Terai of Nepal. Soc Sci Med 199846879–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brieger W R, Oshiname F O, Ososanya O O. Stigma associated with onchocercercal skin disease among those affected near the Ofike and Oyan rivers ion Western Nigeria. Soc Sci Med 199847841–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Awolola T S, Manafa O U, Rotimi O O.et al Knowledge and beliefs about causes, transmission, treatment and control of human onchocerciasis in rural communities in south western Nigeria. Acta Trop 200076247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ovuga E B, Okello D O, Ogwal‐Okeng J W.et al Social and psychological aspects of onchocercal skin disease in Nebbi district, Uganda. East Afr Med J 199572449–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards F, Klein R E, Gonzales‐Peralta C.et al Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions (KAP) of onchocerciasis: a survey among residents in an endemic area in Guatemala targeted for mass chemotherapy with ivermectin. Soc Sci Med 1991321275–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitworth J A, Alexander N D, Seed P.et al Maintaining compliance to ivermectin in communities in two west African countries. Health Policy Plan 199611299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akogun O B, Akogun M K, Audu Z. Community‐perceived benefits of ivermectin treatment in northeastern Nigeria. Soc Sci Med 2000501451–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onwujekwe O E, Shu E N, Okonkwo P O. Community financing of local ivermectin distribution in Nigeria: potential payment and cost‐recovery outlook. Trop Doct 20003091–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hubley J. Community participation—putting the community into community eye health. Community Eye Health 19991233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnstein S R. A ladder of citizen participation. American Institute of Planners Journal 196935216–224. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rifkin S B, Muller F, Bichmann W. Primary health care: on measuring participation. Soc Sci Med 198826931–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rifkin S B. Lessons from community participation in health programmes. Health Policy and Planning 19861240–249. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutter E E, Ballard R C. Community participation in the control of trachoma in Gazankulu. Soc Sci Med 1983171813–1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maphorogo S, Sutter E.The community is my university—a voice from the grass roots on rural health and development. Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, 20031–272.

- 30.Karsson E L. Care groups and primary health care in rural areas. Israel J Med Sci 198319731–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynch M, West S K, Munoz B.et al Testing a participatory strategy to change hygiene behaviour: face washing in central Tanzania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 199488513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okeibunor J C, Ogungbemi M K, Sama M.et al Additional health and development activities for community‐directed distributors of ivermectin: threat or opportunity for onchocerciasis control? Trop Med Int Health 20049887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kimani V, Klauss V. The role of traditional medicine in ophthalmology in Kenya. Soc Sci Med 1983171827–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mselle J. Visual impact of using traditional medicine on the injured eye in Africa. Acta Trop 199870185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Courtright P. Eye care knowledge and practices among Malawian traditional healers and the development of collaborative blindness prevention programmes. Soc Sci Med 1995411569–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Courtright P, Lewallen S, Kanjaloti S. Changing patterns of corneal disease and associated vision loss at a rural African hospital following a training programme for traditional healers. Br J Ophthalmol 199680694–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yusuf H K M, Islam N M. Improvement of nightblindness situation in children through simple nutrition education intervention with the parents. Ecol Food Nutr 199431247–256. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walt G, Perera M, Heggenhougen K. Are large‐scale volunteer community health worker programmes feasible? The case of Sri Lanka. Soc Sci Med 198929599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brieger W R, Ramakrishna J, Adeniyi J D.et al In: Carlaw R, Ward B, eds. Primary health care: the African experience. Oakland, California: Third Party Publishing Company, 1988341–371.

- 40.Johnson‐Welch C.Focusing on women works: research on improving micronutrient status through food‐based interventions. Washington DC: International Centre for Research on Women, 19991–30.

- 41.Hagenimana V, Oyunga M A L J, Njoroge N.et alThe effect of women farmers'adoption of orange‐fleshed sweet potatoes; raising vitamin A intake in Kenya. Washington DC: International Centre for Research on Women, 19991–24.

- 42.Ayalew W, Gebriel Z W, Kassa H.Reducing vitaimin A deficiency in Ethiopia: Linkages with a women‐focused dairy goat farming project. Washington DC: International Centre for Research on Women, 19991–27.

- 43.Molukozi G, Mselle L, Mgoba C.et alImproved solar drying of vitamin A‐enriched foodsby womens groups in Singida District in Tanzania. Washington DC: International Centre for Research on Women, 19991–28.

- 44.Shu E N, Okonkwo P O, Onwujekwe E O. Health education to school children in Okpatu, Nigeria: impact on onchocerciasis‐related knowledge. Public Health 1999113215–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Sole G, Martel E. Test of the prevention of blindness health education programme for Ethiopian primary schools. Int Ophthamol 198811255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joseph M V, Hubley J H.Schools and primary health care—a slide set on the Kangazha school health project in Kerala, India. St Albans: Teaching Aids at Low Cost, 1984

- 47.Limburg H, Vaidyanathan K, Dalal H P. Cost‐effective screening of school children for refractive errors. World Health Forum 199516173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murthy G V S. Vision testing for refractive erors in schools. Community Eye Health 2000133–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ajuwon A J, Oladepo O O, Sati B.et al Improving primary school teachers' ability to promote visual health in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int Q Commun Health Educ 199716219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hawes H, Scotchmer C.Children for health. London, New York: Child‐to‐Child Trust/UNICEF, 1993185pp

- 51.Francis V W B.The healthy eyes activity book—a health teaching book for primary schools. London: International Centre for Eye Health, 2001

- 52.Hawes H, Nicholson J, Bonati G.Children, health and science: Child‐to‐child activities and science and technology teaching. Science and Technology Education Document Series No 41. ED‐91/WS/38 , ed. Paris: UNESCO, 1991122pp

- 53.Murthy G V, Gupta S K, Dada V K.et al The use of a newspaper insertion to promote DIY testing of vision in India. Br J Ophthalmol 200185952–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seidel REed Strategies for promoting Vitamin A production, consumption and supplementation—four case studies. Washington: Academy for Educational Development, 19961–79.

- 55.Smitasiri S, Dhanamitta S.Sustaining behaviour change to enhance micronurent status: community and women‐based interventions in Thailand. Washington DC: International Centre for Research on Women, 19991–27.

- 56.Hoare K, Hoare S, Rhodes D.et al Effective health education in rural Gambia. J Trop Pediatr 199945208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cintra F A, Costa V P, Tonussi J A G.et al Avaliaçäo de programa educativo para portadores de glaucoma [Evaluation of an educational program for patients with glaucoma]. Rev Saude Publica 199832495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosenthal A R, Zimmerman J F, Tanner J. Educating the glaucoma patient. Br J Ophthalmol 198367814–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sil A K. The role of patient counsellors in increasing the uptake of cataract surgeries and IOLs. Community Eye Health 1998118–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rahmathullah Patient counsellors/helpers—a concept developed by Aravind Eye Hospital, Madurai, South India. Community Eye Health 1993622 [Google Scholar]

- 61.World Health Organization Elimination of Global Blindness Agenda item 14.17 56th World Health Assembly. WHA56.26. 28‐5‐ 2003

- 62.Dandona R, Dandona L, John R K.et al Awareness of eye diseases in an urban population in southern India. Bull World Health Organ 20017996–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.World Health Orgainzation Advocacy—a practical guide with polio eradication as a case study. Geneva: WHO/VAB/99, 20 World Health Organization 19991–39.

- 64.World Health Orgainzation TB advocacy—a practical guide. Geneva: WHO/TB/98, 239 WHO Global Tuberculosis Programme 19991–42.

- 65.International Planned Parenthood Federation Advocacy guide for sexual and reproductive health and rights. London: International Planned Parenthood Federation, 2001

- 66.Hubley J H, Green J. In: Commonwealth Secretariat, ed. Health in the Commonwealth—challenges and solutions 1998/9. London: Commonwealth Secretariat/Kensington Publications Ltd, 199986–90.

- 67.Hubley J. In: Scriven A, Garman S, eds. Promoting health: global perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2005147–166.