Abstract

Background/aims

Eyes with burnt out disciform scars secondary to age related macular degeneration (AMD) are regarded as visually stable. The aim of this study is to report the subsequent development of atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) around the scars and discuss the possible basis.

Methods

20 eyes from 18 patients were observed to develop atrophy around choroidal neovascularisation (CNV). A method of measuring expansion of the atrophy over time is described using the Topcon Imagenet 2000 system. An additional 10 clinicopathological examples were reviewed.

Results

Clinically CNV became surrounded initially by a ring of pallor that progressed to an expanding band of atrophy of the RPE. It developed most rapidly in the first 3 years after CNV became quiescent but then continued to expand slowly to more than three times the size of the scar. Histopathological specimens showed large choroidal vessels entering the scars directly and a reduced number of small choroidal vessels beneath and around the scar

Conclusions

Disciform scars may become surrounded by an expanding band of atrophy of the RPE, postulated to result from remodelling of the choroidal circulation. The ongoing enlargement of the resulting scotoma may need to be considered when planning management and assessing treatment outcomes.

Keywords: choroidal neovascularisation, geographic atrophy

A disciform fibrovascular scar is the end result of neovascular age related macular degeneration (AMD) and, since scars nearly always involve the fovea, there is severe loss of central vision. As the angiogenic stimulus declines the scars become less vascular and more fibrotic1 and, once disciform scars have become clinically inactive, eyes are generally regarded as visually stable. If the second eye becomes affected it is likely to develop a similar scar2 and the patient will be directed to support programmes, so that clinical follow up may be lost. However, scars commonly become surrounded by a ring of atrophy that expands over many years, considerably enlarging the scotoma. This ongoing deterioration may need to be considered when assessing treatment outcomes and planning support programmes.

The aim of this study was to document the development of atrophy around disciform scars during long term clinical follow up. The possible basis for the atrophy is considered and explored further in clinicopathological material.

Material and methods

This study reports the evolution of atrophy in 20 eyes from 18 patients aged 52–87 years (mean 68.1) at the time of presentation with choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) and followed for up to 19 years. Eyes were included that had been treated with laser photocoagulation, radiotherapy, intravitreal triamcinolone injections, or combinations of these. None had undergone photodynamic therapy. Eyes with myopic fundi, pre‐existing atrophy, or known rips were excluded.

The expansion of atrophy was assessed in serial 35 mm colour photographs taken with the Topcon 50VT fundus camera. All photographs used had been taken with a 50° field of view because the atrophy often extended beyond the limits of the 30° photographs used in other studies.3 Fluorescein angiography had been performed with the Zeiss fundus camera and at least on one occasion with the Topcon Imagenet 2000 system.

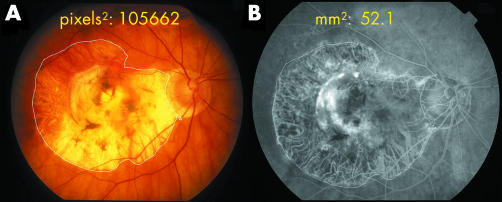

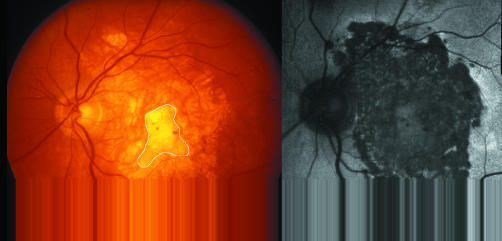

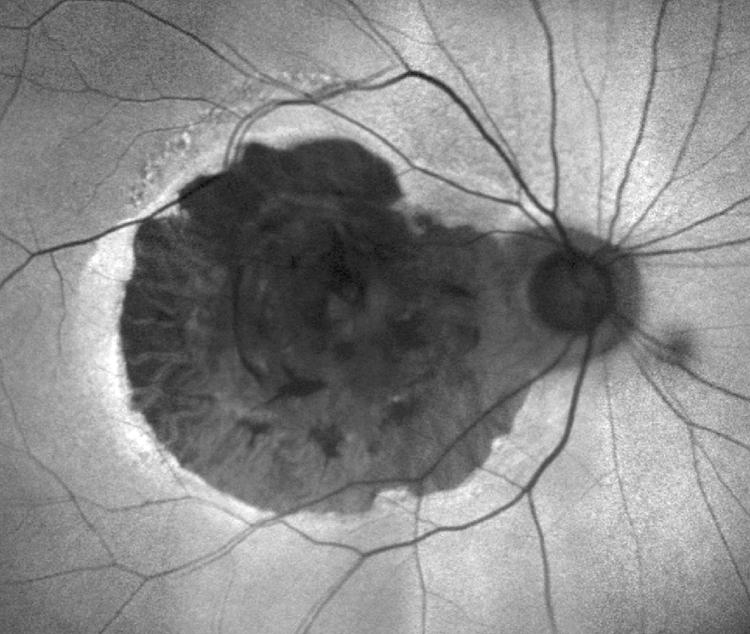

The earlier 35 mm colour slides were first scanned into Adobe Photoshop, the hue occasionally being enhanced to better outline the edge of the atrophy. The uncropped images were then imported into the Imagenet. By tracing around the area of atrophy on the imported image the area was obtained in square pixels (fig 1A). Using fixed landmarks the identical area appeared simultaneously on the Topcon 2000 image expressed in mm2 (fig 1B) and a comparison of images obtained on the same date provided the ratio of square pixels to mm2. The areas of atrophy could then be measured on the imported images of earlier photographs and converted to mm2 using this ratio. The size of the atrophy was also compared to the size of the scars, although the outlines of the fibrous tissue within the atrophy were not always sharply defined. Fundus autofluorescence using the Heidelberg retina angiograph confirmed the atrophy but was performed on only seven eyes.

Figure 1 (A) A 35 mm uncropped 50° colour fundus photograph imported into Imagenet 2000, showing fibrotic disciform scar surrounded by wide zone of atrophy. Area is expressed in square pixels. (B) Fluorescein angiogram obtained with Imagenet 2000 on same occasion at same magnification. Comparison of images indicates 1 mm2 is equivalent to 2028 square pixels. This ratio was then applied to older fundus photographs (see Methods). Man aged 81, scar measures 9 mm2, atrophy has enlarged non‐functioning area to 52.1 mm2. The evolution of atrophy in this eye is illustrated in figures 2–5.

Note was also made of whether the development of atrophy was related to blood or exudate, vascular communications between the scar and the retina, previous treatment of the CNV, or the presence of geographic atrophy (GA) in the fellow eye. The only test of visual function performed was the corrected Snellen visual acuity.

Clinicopathological study

Ten eyes seen clinically with established disciform scars and surrounding atrophy were selected from a large clinicopathological collection of postmortem eyes. The eyes belonged to six patients whose ages ranged from 76–92 years at death (mean 82.3).

The eyes had been paraffin embedded, sectioned in the horizontal plane, and stained predominantly with the picro‐Mallory stain described previously.4 Light microscopy was performed on a minimum of three sections from each eye to determine the nature and extent of degeneration beyond the temporal edge of the scar. The nasal side was not assessed owing to the presence of peripapillary atrophy.

Results

The mean age at which CNV developed was 68.1 years and the mean age at which measurement of atrophy commenced was 72.8 years. Since the measured area represented the combined size of the scar plus the surrounding atrophy, measuring the expansion of atrophy alone could be commenced only after the scar was stable.

Case history

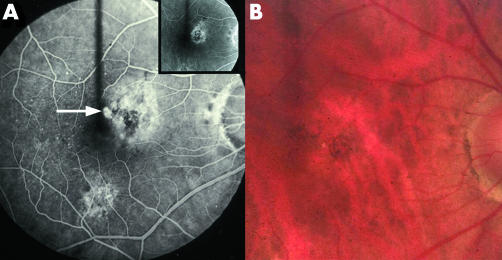

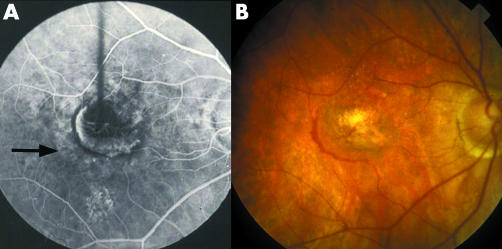

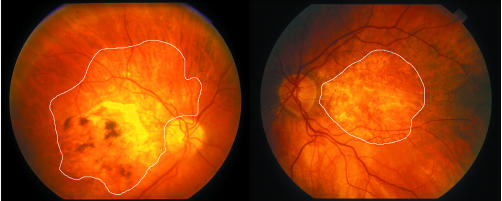

Figures 2–5 illustrate the clinical evolution over 19 years of the eye shown in figure 1. The patient was first seen at age 65 with an occult choroidal neovascular membrane that developed a classic extension 4 years later (fig 2). A band of pallor and hyperfluorescence around the membrane appeared early and, as it expanded, the pallor became more pronounced with a clearer outer border (fig 3). This was interpreted as thinning or incipient atrophy of the RPE. Even after the scar had stabilised precise dating of the onset of true atrophy was not possible on colour photographs, but measurements of the area were commenced when the edge became sharply defined and there was increased visibility of the choroidal vessels (fig 4). The atrophy progressed most rapidly in the first few years, extending to the disc and beyond the major arcades. Subsequently the progress slowed and in this eye there was no measurable increase between age 81 (fig 1) and age 84 (fig 5).

Figure 2 (A) Fluorescein angiogram of man aged 69 who was first seen at age 65 with an asymptomatic occult CNV (inset). He returned with a classic juxtafoveal extension (arrow). (B) Note paler pink areola surrounding the CNV on colour photograph. Krypton laser was applied but the CNV recurred.

Figure 3 (A) Fluorescein angiogram performed 4 months after laser, demonstrating a classic recurrence with feeding vessels, extending laterally and downwards. Vision 6/60. A band of hyperfluorescence that did not increase in size lies beyond the CNV (arrow). (B) After a further month there is an organising recurrence with a rim of blood, beyond which is a wide zone of pallor (incipient atrophy of the RPE).

Figure 4 (A) Seven months after laser the scar appeared stable. Only the lower part of the incipient atrophy was regarded as true atrophy (arrows). (B) By age 73 all the incipient atrophy appeared to be true atrophy in which exposed choroidal vessels were sheathed. The scar is outlined. The recurrence had not involved the upper nasal area and the atrophy is least marked here where the scar had not formed (arrow).

Figure 5 Same eye as shown in figures 1–4. Autofluorescent image at age 84, 19 years after CNV developed, clearly indicates where the RPE is absent. The area was unchanged from age 81 (fig 1) despite a narrow rim of increased autofluorescence caused by accumulated lipofuscin in RPE.

Possible factors influencing atrophy

Although drusen and/or pigment changes had been present at the time that CNV occurred in these eyes, they did not appear to have a role in the development of atrophy. Nor did the atrophy show a relation to previous blood or lipid, communications to the retinal circulation, or treatment of the CNV which had been performed on nine eyes, including thermal laser (1), intravitreal triamcinolone (2), radiotherapy (2), and combinations of these (4). None of the eyes had photodynamic therapy.

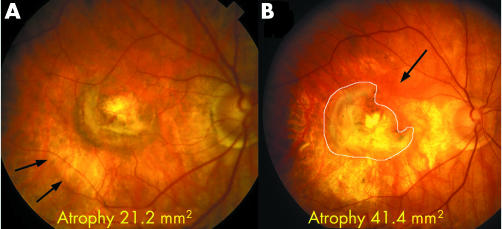

The main determining factor was the presence of the scar, atrophy being least pronounced where the scar had not formed (fig 4B). The age of the scar was more significant than the age of the patient as it could become large even in younger patients and also around small scars (fig 6). The total area affected was a mean of 3.4× (range 1.7–7.5×) larger than the scar alone. It was also unrelated to the development of GA in the fellow eye as 14 patients had CNV in the fellow eye and only two developed GA spontaneously, the affected area being much larger in the eye with atrophy around scars (fig 7).

Figure 6 Fundus photograph and autofluorescent image of 59 year old man, the youngest in the series, who had presented with CNV on a background of drusen at age 52. Despite developing only a small scar, approximately 4.8 mm2 in area (outlined), there was an extensive area of patchy atrophy, confirmed by autofluorescence, measuring 30.5 mm2.

Figure 7 Right and left eyes of 81 year old man who first presented at age 65 with a ring of small drusen and pigment around the foveal perimeter in each eye. The right eye developed CNV followed by atrophy extending even outside the major arcades and measuring 44.4 mm2. The left eye developed geographic atrophy measuring 21.8 mm2, the affected area being only half that of the right eye.

Rate of expansion

The mean follow up of the 20 eyes from the time that atrophy was first measured was 7.3 years. The overall expansion rate over this period was 2.4 mm2 a year, but was more rapid initially (table 1). The intervals when first seen after atrophy commenced varied but 13 of the eyes had their first follow up visit within 3 years of the onset and in these the rate was more rapid—3.3 mm2 a year. Nine of these eyes had been reviewed within the first 2 years of the onset and in these the annual expansion rate was even more rapid at 5.1 mm2 a year.

Table 1 Progression of atrophy around scars.

| Review period | No of eyes | Mean annual expansion rate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| From onset to last visit (mean 7.3 years, range 1–15 years) | 20 | 2.4 mm2 | |

| Within 3 years of onset | 13 | 3.3 mm2 | |

| Within 2 years of onset | 9 | 5.1 mm2 |

Clinicopathological studies

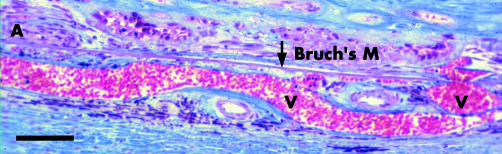

All the scars were extensive, measuring 4770–7000 μm in width. Large vessels occupied almost the entire thickness of the choroid and entered the scar directly (fig 8), so that there was loss of the choriocapillaris and middle layer of choroidal vessels and the stroma appeared fibrotic. Many small vessels were evident in the scar but did not extend to the edge. Two scars had blood over the surface but no blood or exudation was present at the temporal edge.

Figure 8 Section showing choroid beneath part of an extensive scar of an 82 year old man who developed CNV at age 78. Artery (A) and vein (V) pass through Bruch's membrane (Bruch's M). Note vein occupies most of the choroid. Other arteries in choroid show adventitial fibrosis. These feeding and draining vessels bypass the smaller choroidal vessels. Blood supply has therefore been redirected to the scar rather than the choroid. Bar marker 100 μm. Picro‐Mallory stain.

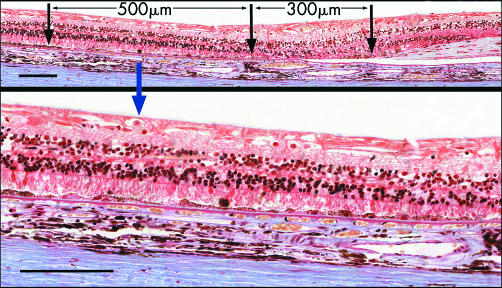

Atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) was present beyond the edges of the scar. On the nasal side all eyes had peripapillary atrophy extending 270–550 μm from the disc margin. On the temporal side the atrophy measured 280–620 μm from the edge of the scar. Here there were no photoreceptors or RPE and the loss of smaller choroidal vessels and choriocapillaris seen under the scar continued into this zone (fig 9). At the junctional zone at the edge of the atrophy there was mild hypertrophy of the RPE. However, the RPE was abnormal for a further 300–600 μm and, when pronounced, the RPE in this zone showed alternating attenuation and hyperpigmentation overlying a thin basal laminar deposit (fig 9). Photoreceptor nuclei were fewer and the outer segments were stunted, while the choroidal capillaries were separated by widened intercapillary pillars. However, in drawing comparison with the clinical cases it should be noted that the mean age of these patients was 14 years older.

Figure 9 (Top) Section showing, at right, the temporal edge of long standing disciform scar of 76 year old man. Area of atrophy in which smaller choroidal vessels are absent extends 300 μm beyond edge of scar. Further temporally is a wider zone (500 μm) in which RPE is abnormal, magnified below. Picro‐Mallory stain. Bar marker 100 μm. (Bottom) Higher magnification of abnormal zone beyond atrophy, showing attenuation of RPE and shedding of hyperpigmented cells. Photoreceptors are stunted. A thin layer of basal laminar deposit is present. There is fibrosis of the choroid. Picro‐Mallory stain. Bar marker 100 μm.

Discussion

The atrophy that develops around disciform scars shows certain differences from GA in AMD (table 2). The latter can demonstrate several patterns. As a primary manifestation it commonly commences around the foveal perimeter and evolves in a bull's eye pattern.5,6,7 As the RPE cells are shed they may impart a hyperpigmented margin to the junctional zone at the edge of the atrophy but this dark rim is not seen as the edge moves further from the parafovea where the expansion slows, and it was not seen in the present study. Fundus autofluorescence, which is derived mainly from lipofuscin in the RPE,8 demonstrates that lipofuscin accumulation occurs around GA9 and can be used to predict the spread of atrophy even when the RPE looks clinically normal.10 Different patterns of fundus autofluorescence around GA can be identified,11 a narrow band (fig 5) being thought to have a better prognosis than more diffuse changes.

Table 2 Clinical comparison between GA in AMD and atrophy around scars.

| GA in AMD | Atrophy around scars | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | Relates to age of patient, hence onset later | Relates to age of scar, usually younger | |

| Distribution | Determined by rod population/drusen/PED | Determined by disciform scar | |

| Initial progress | Slow | More rapid | |

| Extent | Mainly confined to inner macula | Commonly extends into outer macula and beyond | |

| Margin | Commonly hyperpigmented | Not hyperpigmented | |

| Fellow eyes | Most have GA | Most have CNV |

AMD, age related macular degeneration; CNV, choroidal neovascularisation; GA, geographic atrophy; PED, pigment epithelial detachment.

The commonest form of GA in AMD is actually a multifocal distribution secondary to the regression of drusen, while the least common is a central location secondary to collapse of a pigment epithelial detachment (PED). Atrophy around scars, however, was not consistently preceded by such pigment changes or drusen.

Table 2 shows some of the main clinical differences between GA in AMD and atrophy around scars, but comparisons with AMD are made difficult because of the variable size used to define GA. This has varied from 200 μm,12 to 700 μm,13 to 1 mm5 but there is agreement that the prevalence shows a marked increase after age 75.12 Atrophy around scars occurs at a younger age, reflecting the earlier age at which CNV occurs. In AMD GA is most often bilateral and the size and configuration of the GA tends to be symmetrical between eyes,14 whereas in this study only two patients developed GA in the fellow eye. Atrophy around scars also progressed more rapidly in the first 3 years than GA. Sunness et al14 found that the mean rate of enlargement of GA over a 2 year period was 5.6 mm2. whereas in this series the rate was almost double this for the first 2 years (5.1 mm2 per year). The average rate of expansion in one direction has been measured at 130 μm per year15 but spread was often asymmetrical around the scar and therefore measurement of area rather than diameter was preferred.

The pathogenesis of the atrophy did not appear to be determined by previous blood or exudation beneath the RPE, by the development of GA in the fellow eye, or by the age of the patient. Nor was the final result significantly influenced by treatment of the CNV although the effect of photodynamic therapy, which has been shown to reduce perfusion in the choroid surrounding the treated CNV,16 remains to be established.

The initial halo of fundus pallor and hyperfluorescence around CNV appeared early. This can be taken as a sign of active CNV that is drawing on the choroidal circulation and so can be a predictor of future atrophy. It is speculated that the primary event is a remodelling of the choroidal circulation as a result of vascularisation of the scar bypassing the smaller choroidal vessels. At the time of active CNV the greatest demands are made on the choroidal blood supply and possibly this “steals” blood from the choroid. A reduced blood flow to the smaller choroidal vessels around the scar would throw the larger vessels into greater prominence and so contribute to their heightened visibility clinically, as well as predisposing to attenuation and ultimately atrophy of the RPE. That ischaemia may have such a role is suggested by the study of eyes with early AMD manifesting larger drusen but with good visual acuity, in which delayed choroidal perfusion can be demonstrated on fluorescein angiography17 and reduced foveal choroidal blood flow on laser Doppler flowmetry.18 Communications to the retinal circulation did not prevent the atrophy since the initial source of blood supply to the scar remains the choroid.

Nevertheless, attributing a primary role to the choroid does not exclude a loss of the normal trophic influences exerted on the choriocapillaris by the RPE. If the RPE cells were migrating towards the scar as a result of release of contact inhibition, the cells may not have the required density to sustain the choriocapillaris19 and, once in the area of choriocapillaris atrophy, the cells would die. A similar mechanism could apply to the expansion of laser induced atrophy following grid photocoagulation of diabetic macular oedema.20

The functional impact of the atrophy was not assessed in this study. Only the visual acuity was tested as in most cases the patient was attending to monitor the fellow eye, but there is evidence that reading rate is inversely related to the size of the atrophy.21 Moreover, microperimetry demonstrates reduced retinal sensitivity around GA,22 possibly related to the abnormal retina beyond the atrophy.

Conclusions

On fundus examination CNV is often surrounded by a pink areola, apparently caused by reduced vascularity in the adjacent choroid resulting from diversion of blood to the CNV. This band develops into incipient atrophy of the RPE and then true atrophy with a well defined margin and increasing exposure of the larger choroidal vessels because of loss of the smaller vessels. It is postulated that this atrophy results from remodelling of the choroidal circulation, the vascularised scar “stealing” blood from the choroid. A method for measuring changes in area on 50° colour photographs is described using the Topcon Imagnet 2000, making it possible to demonstrate expansion of the atrophy over many years. Initially this was found to progress more rapidly than GA in AMD.

The practical implication is that patients with disciform scars may not be visually stable. Such patients may not be encouraged to return and may not be managing as well as was thought. Since the atrophy around scars can expand the size of the non‐functioning retina by a mean of 3.4 times, the impact of the enlarging scotoma may need to be considered when evaluating treatment outcomes and planning support programmes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Svetlana Cherepanoff for assistance with the manuscript, Ms Adeline Akkari for assistance with the histological photographs, and Mr Bevan Regan for advice on the Topcon Imagenet 2000.

Abbreviations

AMD - age related macular degeneration

CNV - choroidal neovascularisation

GA - geographic atrophy

PED - pigment epithelial detachment

RPE - retinal pigment epithelium

Footnotes

The study protocol was approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee.

References

- 1.Holz F G, Pauleikhoff D, Spaide R F.et al In: Age‐related macular degeneration. Berlin: Springer‐Verlag, 200481

- 2.Lavin M J, Eldem B, Gregor Z J. Symmetry of disciform scars in bilateral age‐related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol 199175133–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sunness J S, Bressler N M, Tian Y.et al Measuring geographic atrophy in advanced age‐related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999401761–1769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarks S H. Ageing and degeneration in the macular region: a clinico‐pathological study. Br J Ophthalmol 197660324–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarks J P, Sarks S H, Killingsworth M C. Evolution of geographic atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Eye 19882552–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curcio C A, Millican C L, Allen K A.et al Aging of the human photoreceptor mosaic: Evidence for selective vulnerability of rods in central retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1993343287–3296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dandekar S S, Jenkins S A, Mann R A J.et al Regional susceptibility of the retina to geographic atrophy and how it progresses over time. London: Moorfields Eye Hospital, Poster, RCO Annual Congress 2004

- 8.Delori F C, Goger D G, Dorey C K. Age‐related accumulation and spatial distribution of lipofuscin in RPE of normal subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001421855–1866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Von Rückman A, Fitzke F W, Bird A C. Fundus autofluorescence in age‐related macular disease imaged with a laser scanning ophthalmoscope. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 199738478–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holz F G, Bellman C, Staudt S.et al Fundus autofluorescence and development of geographic atrophy in age‐related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001421051–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bindewald A, Schmitz‐Valckenberg S, Jorzik J J.et al Classification of abnormal fundus autofluorescence patterns in the junctional zone of geographic atrophy in patients with age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol 200589874–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein R, Klein B E K, Linton K L P. Prevalence of age‐related maculopathy. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology 199299933–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bressler N M, Bressler S B, West S K.et al The grading and prevalence of macular degeneration in Chesapeake Bay watermen. Arch Ophthalmol 1989107847–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sunness J S, Gonzalez‐Baron J, Applegate C A.et al Enlargement of atrophy and visual acuity loss in the geographic atrophy form of age‐related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 19991061768–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schatz H, McDonald R. Rate of spread of geographic atrophy and visual loss. Ophthalmology 1989961541–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt‐Erfurth U, Michels S, Barbazetto I.et al Photodynamic effects on choroidal neovascularization and physiologic choroid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200243830–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holz F G, Wolfensberger T J, Piguet B.et al Bilateral macular drusen in age‐related macular degeneration: prognosis and risk factors. Ophthalmology 19941011522–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grunwald J E, Metelitsina T I, Dupont J C.et al Reduced foveolar choroidal blood flow in eyes with increasing AMD severity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005461033–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castellarin A A, Nasir M, Sugino I K.et al Progressive presumed choriocapillaris atrophy after surgery for age‐related macular degeneration. Retina 199818143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schatz H, Madeira D, McDonald H R.et al Progressive enlargement of laser scars following grid laser photocoagulation for diffuse diabetic macular edema. Arch Ophthalmol 19911091549–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sunness J S, Applegate C A, Haselwood D.et al Fixation patterns and reading rates in eyes with central scotomas from advanced atrophic age‐related macular degeneration and Stargardt disease. Ophthalmology 19961031458–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitz‐Valckenberg S, Bültmann S, Dreyhaupt J.et al Fundus autofluorescence and fundus perimetry in the junctional zone of geographic atrophy in patients with age‐related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45: 4470–6; erratum in Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2005467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.