Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the efficacy, safety, and therapeutic effect of topical ciclosporin A 0.05% as a steroid sparing agent in steroid dependent allergic conjunctivitis.

Methods

Prospective, randomised, double masked, placebo controlled trial comparing signs, symptoms, and the ability to reduce or stop concurrent steroid in steroid dependent atopic keratoconjunctivitis and vernal keratoconjunctivitis using 0.05% topical ciclosporin A compared to placebo. Steroid drop usage per week (drug score), symptoms, and clinical signs scores were the main outcome measures.

Results

The study included an enrolment of 40 patients, 18 with atopic keratoconjunctivitis and 22 with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. There was no statistical significant difference in drug score, symptoms, or clinical signs scores between the placebo and ciclosporin group at the end of the treatment period. No adverse reactions to any of the study formulations were encountered.

Conclusions

Topical ciclosporin A 0.05% was not shown to be of any benefit over placebo as a steroid sparing agent in steroid dependent allergic eye disease.

Keywords: topical ciclosporin A, atopic keratoconjunctivitis, vernal keratoconjunctivitis, steroid dependent allergic conjunctivitis

Allergic eye disease is a common debilitating ocular surface disease that is highly variable in severity and duration. Milder disease is more common and does not affect the cornea, but the most serious forms of ocular allergic disease—atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) and vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC)—may involve the cornea and can be sight threatening.1,2,3 Treatment is directed towards the allergic response with antihistamines and mast cell stabilisers are the mainstay of therapy. Severe or resistant diseases are well recognised and steroids are frequently required. Steroids can be highly effective, but may cause unwanted elevation of intraocular pressure in steroid responders and increase the risk of corneal infection through local immunosuppression. In addition, induction of cataract and delayed wound healing can be problematic.

Ciclosporin A is a non‐steroidal immunomodulator that inhibits antigen dependent T cell activation. Ciclosporin also has a direct inhibitory effect on eosinophil and mast cell activation and release of mediators, which is likely to be important in allergic inflammation.4,5,6,7

Topical ciclosporin has been used in several formulations in an effort to reduce steroid dependence. A placebo controlled trial using topical ciclosporin 2% in maize oil showed it to be an effective and safe steroid sparing agent, but its use was limited by frequent intense stinging in the patients.8 In a large series of patients with AKC, significant keratopathy developed in two thirds of patients managed with the usual regimen of oral antihistamines, topical mast cell stabilisers, and topical steroids.9 A randomised controlled trial (RCT) using a novel emulsion of ciclosporin A 0.05% in topical steroid resistant AKC, showed a much better tolerated treatment that had some effect in alleviating signs and symptoms of AKC.3 We undertook a prospective randomised double masked study to assess, the therapeutic effect of topical ciclosporin 0.05% as a steroid sparing agent in steroid dependent allergic conjunctivitis.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a prospective double masked, RCT, comparing signs, symptoms, and the ability to reduce or stop concurrent steroid in steroid dependent AKC or VKC using 0.05% topical ciclosporin A compared to placebo.

Patients

The human research ethics committee of the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital approved the study protocol. Patients of either sex with steroid dependent AKC or VKC, who were willing to comply with the protocol and who provided informed consent, were recruited from the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital corneal clinic. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the initiation of any study medication or study related procedure.

Patients were excluded from the study if they where using systemic steroid or immunosuppressive drugs or non‐steroid anti‐inflammatory medication or had associated ocular infections or coexisting ocular diseases such as corneal diseases, glaucoma, and optic atrophy. If patients were using topical or systemic ciclosporin, this medication was discontinued 2 weeks before the start of the trial.

Other exclusion criteria included history of periocular injections of steroids within a period of 6 months, ocular surgery within the previous 6 months, and using steroid eye drops for reasons other than allergic diseases (that is, uveitis)

Pregnant or lactating mothers were also excluded. Patients could be discontinued before the completion of the study owing to adverse events, protocol violations, lack of efficacy, or personal reasons.

Study protocol

Patients were assigned randomly based on a predetermined randomisation list generated by computer to receive either 0.05% topical ciclosporin A (Restasis, Allergen, Irvine, CA, USA) or placebo (vehicle). Allocation coding was undisclosed until all patients had completed the study. Both patients and physicians were masked to the identity of the drops used for the duration of the trial. Identical unit dose vials were used to hold the study treatments.

During the treatment phase, all patients were instructed to instil one drop of the study medication (0.05% ciclosporin A or placebo eye drops) four times daily to both eyes, in addition to their usual treatment. The clinical response was used to reduce and stop topical steroids when possible. During the treatment phase, patients returned for evaluation after 1 week, 1, 2, and 3 months of treatment.

Outcome measures

Parameters used to assess treatment outcomes included symptoms, signs, and reduction or cessation of steroids. Symptoms of itch, redness, tearing, soreness (burning, discomfort, foreign body sensation) discharge, and photophobia were graded and recorded at each visit by the clinician on questioning. Clinical signs were graded by the physicians for the lids (ptosis, lid skin dermatitis, lid margin thickening, lid margin thickening, lid margin distortion, and lid margin hyperaemia) for the conjunctiva (hyperaemia and oedema for the bulbar conjunctiva, hyperaemia, infiltration and papillae for inferior conjunctiva, and subepithelial conjunctival scarring, cicatrisation, hyperaemia, infiltration, and papillae for the superior tarsal conjunctiva) and for the cornea (tear film deficiency, epithelial disease, opacity, stromal thinning, neovascularisation, lipid deposition).

Topical steroid drops were modulated according to the clinical response. Steroid drop usage per week was calculated as the “drug score.” Allowances were made for the relative potency of different topical steroid preparations by using a multiplication factor (that is, number of drops per week multiplied by five for prednisolone acetate 1%, by four for dexamethasone 0.1%, by three for fluoromethalone 0.1%, by two for prednisolone phosphate 0.3%, and by one for prednisolone phosphate 0.1%).

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were conducted with Statistical Analysis System (SAS version 9.1 for windows, SAS Institute, Cary, NY, USA). Scores were derived separately for symptoms, signs, and steroid drug usage. We used the t tests to compare between the placebo and treatment groups the scores at a given time point or the reduction of scores from the initial to the final time point. We need to use t tests, as the number of observations in each group was fewer than 25. We also considered the binary outcomes that are indicators of the presence of a symptom or score, and used the logistic regressions to compare between the treatment or placebo groups the proportions of the presence of a symptom or sign at a time point. To examine the change over time for an outcome we used the generalised linear models with an exchangeable working correlation that allows dependency between observations from the same patient.10 The generalised linear models were used with a normal distribution and log link for the drug, symptom, and sign scores, and the generalised models with a binomial distribution and log link for binary outcomes. The log link for the scores showed that the scores decreased exponentially with time. A test with a p value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

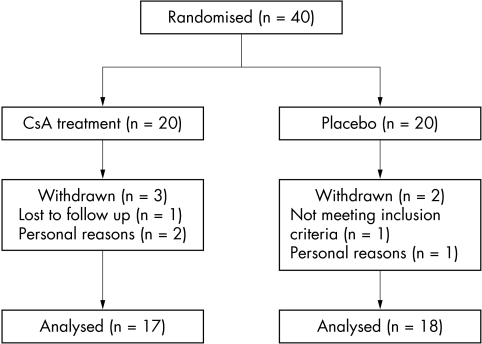

Of the 40 patients with steroid dependent allergic eye disease 20 patients were assigned to receive 0.05% topical ciclosporin A and 20 to receive placebo. Five patients were discontinued from the study. Of the five that discontinued, three were in the CsA treatment group (one was lost to follow up after enrolment and two withdrew for personal reasons) and two of these were in the placebo group (one was found not to meet the study criteria after randomisation and one withdrew for personal reasons). Thus, for description and analysis 35 patients were used (17 in the treatment group and 18 in the placebo group) (fig 1). At the time of enrolment 15 patients were diagnosed with steroid dependent AKC (eight patients in the treatment group) and 20 patients with steroid dependent VKC (nine in the treatment group). No adverse reactions to any of the study formulations were encountered.

Figure 1 Randomisation of participants. (CsA, ciclosporin A.)

Of 17 patients in the CsA treatment group, 15 (88%) were males and their age mean at presentation was 26.2 years (SD 18). Of 18 patients in the placebo group, 13 (72%) were male and the age mean at presentation was 26.2 years (SD 16.3). There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of sex or age.

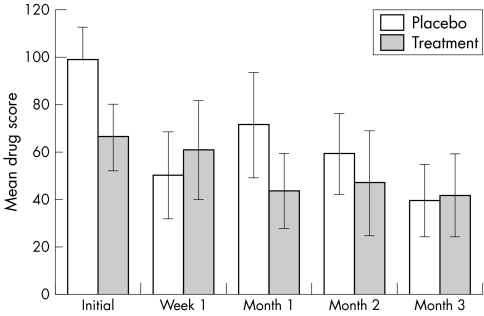

The initial weekly steroid drop usage score was 99.3 (SD 45.1) in the placebo group, and 66.5 (SD 45.9) for the CsA treatment group (fig 2). There was a marginally significant difference between the two groups in the initial weekly steroid drop usage score (p = 0.05). The final steroid drop usage score was 39.9 (SD 45.8) for the placebo group, and 42 (SD 44.7) for the treatment group. However, there was no significant difference in the final steroid drop usage score between the two groups (p = 0.9). Also the reduction in steroid drop usage score in the placebo group was not significantly different from that in the treatment group (p = 0.6).

Figure 2 Mean (SEM) steroid drop usage per week (drug score) before and during the trial.

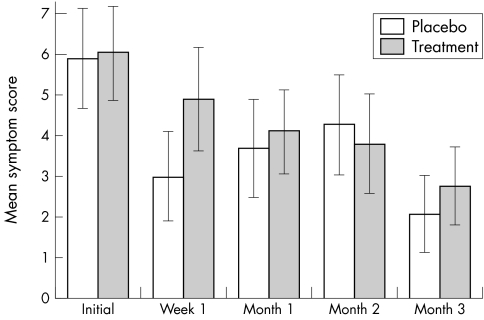

The initial symptom score was 5.9 (SD 4.3) for the placebo group, and 6.1 (SD 4.0) for the treatment group while the final score was 2.1 (SD 2.9) for the placebo group and 2.8 (SD 3.1) for the treatment group (fig 3). There was no significant difference in either initial symptom score (p = 0.9) or final symptom score (p = 0.5). However, there were significant reductions over time in itching (p = 0.04), and redness (p = 0.01) for the CsA treatment group. The placebo group also experienced significant reduction over time in redness (p = 0.01) and white discharge (p = 0.01). All the other symptoms did not attain statistical significance of change over time in either placebo or treatment CsA group.

Figure 3 Mean (SEM) symptom score before and during the trial.

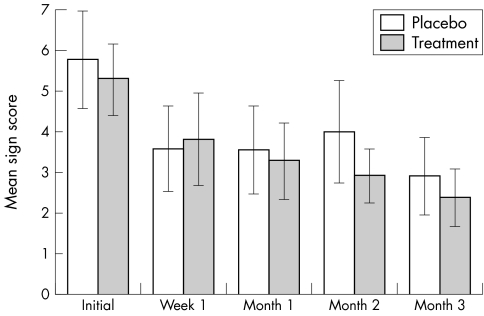

Finally, there was no significant difference between the placebo and treatment groups in the initial clinical sign score (p = 0.7) or the final clinical score (p = 0.6) (fig 4). For specific signs, patients in the treated group showed significantly greater improvement over time in the lid margin thickening (p = 0.02), inferior and superior conjunctiva hyperaemia (p = 0.01 and p = 0.01 respectively), inferior conjunctiva papillae (p = 0.03), and corneal tear film deficiency (p = 0.05). The placebo group showed significant reduction over time in bulbar conjunctiva hyperaemia (p = 0.02). The other signs did not attain statistical significance of change over time in either of the groups.

Figure 4 Mean (SEM) sign score before and during the trial.

Discussion

The results of our trial failed to show a beneficial effect from the addition of topical ciclosporin 0.05% in steroid dependent allergic eye disease. In various parameters including symptom score, sign score, and drug score, there was no statistically significant difference between treatment and placebo groups over the period studied.

Our study population included patients with steroid dependent AKC and VKC and examined the effect of topical ciclosporin A (0.05%) on symptoms and signs or a steroid sparing effect. It was masked, randomised, and prospective and used vehicle as the placebo control. Although there was a difference in composite drug scores between the groups at baseline, other baseline parameters were equivalent. No significant difference in reduction of steroid was noted over the study period. The trial instruction was to use the clinical response to guide the reduction in topical steroid drops and to reduce as possible. The individual decision to reduce steroids was made by the treating clinician.

The symptom score used is a well validated tool and similar to those used in previous studies.3,8 Similarly, the signs score has been used previously.3,8 In addition to the primary analysis using the aggregated scores we also examined each feature individually and found no statistically significant pattern.

A negative result of this study is in contrast with a recent multicentre trial using the same preparation as in our study. Topical ciclosporin A 0.05% in a novel emulsion (Restasis) in 22 patients with AKC refractory to steroid treatment, showed some beneficial effect on pooled symptoms and signs scores over the treatment period without adverse effects.3 However, that trial compared ciclosporin with a placebo (artificial tears) non‐vehicle and was limited by a small sample size (22 patients) and a relatively short duration. Steroid use was maintained at pre‐enrolment levels.

In a smaller prospective RCT in similar patient groups, the study by Hingorani et al used topical ciclosporin A 2% in maize oil, which had been manufactured in the pharmacy at Moorfields Hospital. Twenty one patients with steroid dependent AKC were studied and ciclosporin was shown to have a greater steroid sparing effect than that of vehicle albeit at the cost of poor patient tolerance of the adjunctive therapy.8

With 40 patients, our study had an 80% study power to detect a 0.45 difference in the proportion of patients stopping steroid in either group. To detect a smaller difference of 0.20, we would have needed 82 patients in each group.

The lack of response in this study may indicate that there is no benefit from the topical ciclosporin drops. In acute allergy, there is an immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediated type 1 hypersensitivity reaction, but in chronic disease, this changes to a mixed cell response.11,12 In VKC and AKC, there is a TH‐2 cell mediated chronic inflammation with an increase in CD4+ cells.7 Topical ciclosporin is an anti‐CD4+ cell agent, but acts more specifically on the TH‐1 cells and so theoretically may be of less benefit in allergic TH‐2 cell mediated hypersensitivity.12,13

Alternatively, the dosage of ciclosporin A may have been insufficient. The use of steroid may mask any benefit from ciclosporin drops, although this was not seen in the earlier trials.3,8 Similarly, either the concentration or frequency of treatment may have been too low, although the protocol was similar to previously reported studies.3,8

This study highlights the strengths of a RCT. Our perception and the perception of our patients, together with reports in the literature gave support to the use of adjunctive therapy in steroid dependent allergic eye disease. As no definite benefit has been shown, we have no option but to temper our enthusiasm. One possibility is to repeat a larger and more powerful study. The other option is not to recommend Restasis eye drops (ciclosporin 0.05%) in steroid dependent allergic conjunctivitis.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by Allergan Australia, who supplied the ciclosporin and placebo drops. The authors would also like to thank the corneal unit ophthalmologists at Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital for assessing the subjects taking part in the study. Practically we would like to thank Dr Ramin Salouti for his efforts in setting up the protocol of the study.

Abbreviations

AKC - atopic keratoconjunctivitis

CsA - ciclosporin A

IgE - immunoglobulin E

RCT - randomised controlled trial

VKC - vernal keratoconjunctivitis

Footnotes

The authors have no commercial interest in the findings presented in this paper.

References

- 1.Tanaka M, Dogru M.et al The relation of conjunctival and corneal findings in server ocular allergies. Cornea 200423464–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akova Y A, Rodriguez A, foster C S. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ocular Immun Inflamm 19942125–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akpek E K, Dart J K.et al A randomised trial of topical cyclosporin 0.05% in topical steroid‐resistant atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology 2004111476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nussenblatt R B, Palestine A G. Cyclosporine A: immunology, pharmacology and therapeutic uses. Surv Ophthalmol 198631159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitcup S M, Chan C C, Luyo D A.et al Topical cyclosporine inhibits mast cell‐mediated conjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1996372686–2693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borel J F, Baumann G, Chapman I.et al In vivo pharmacological effects of cyclosporin and some analogues. Adv Pharmacol 199635115–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metz D P, Bacon A S, Holgate S.et al Phenotypic characterization of T cells infiltrating the conjectiva in chronic allergic eye disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 199698686–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hingorani M, Moodaley L.et al A randomized, placebo‐ controlled trial of topical cyclosporin A in steroid‐dependent atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology 19981051715–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Power W J, Tugal‐Tutkun I, Foster C S. Long‐term follow‐up of patients with atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology 1998105637–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCullagh P, Nelder J A.Generalised linear models. 2nd ed. London: Chapman and Hall, 1989

- 11.Allansmith M R, O'Connor G R. Immunoglobulins: structure, function and relation to eye. Surv Ophthalmol 197014367–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGill J I, Holgate S T.et al Allergic eye disease mechanisms. Br J Ophthalmol 1998821203–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosmann T R, Coffman R L. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol 19897145–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]