Short abstract

We need to act now to eliminate preventable blindness by the year 2020

Keywords: refractive error, Vision 2020, myopia, vision impairment

In 1997, the World Health Organization set itself an ambitious goal to eliminate avoidable blindness in the world by 2020, with one of the five main priorities being refractive errors.1,2 A recent review of the impact of Vision 2020 on preventable blindness, other than uncorrected refractive errors, indicates that current estimates of global blindness are less than projected, and thus the trend is in the right direction to meet the Vision 2020 goal for the other conditions.3 The article by Fotouhi et al in this month's issue of BJO (p 534) indicates that we are not doing so well on meeting the goal to eliminate vision impairment caused by uncorrected refractive error in Tehran. At this point, perhaps readers are thinking that the problem of uncorrected refractive error is unique to countries with relatively poorer healthcare systems. Let us consider the paper by Fotouhi et al in the global context of vision impairment caused by refractive errors.

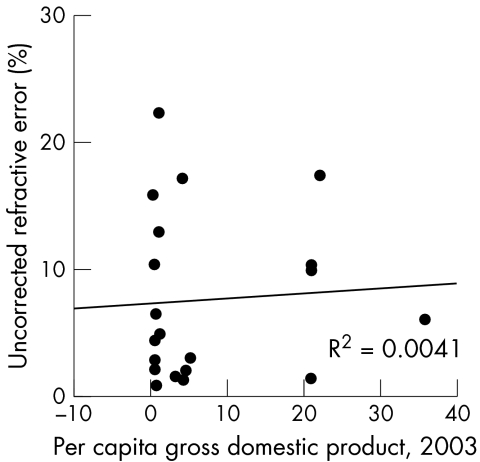

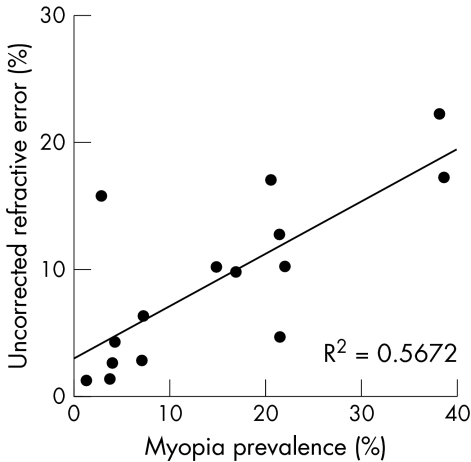

A PubMed search in January 2006 using the search strategy “uncorrected refractive error AND epidemiology” and “undercorrected refractive error AND epidemiology” revealed 19 population based studies of uncorrected refractive errors,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 all of them published since the release of Vision 2020 in 1997. Information abstracted from each article included the age and size of the study cohort, the definition of uncorrected refractive error, the percentage of the study population with uncorrected refractive error, and the myopia prevalence rate, if available (table 1). These data were merged with country specific estimates of per capita gross domestic product for the year 2003 (http://eie.doe.gov/pub/international/iealf/tableb2c.xls) and entered into SPSS for analysis. Simple linear regression was used to quantify the relation between uncorrected refractive error and myopia prevalence and per capita gross national product in 2003. The uncorrected refractive error rate ranged from 0.7% to 22.3% and rose with age, with uncorrected refractive error being the primary cause of moderate vision impairment in most studies. Relative prosperity, as indicated by the per capita gross national product, was not associated with the prevalence of uncorrected refractive error; all countries are doing equally poorly at addressing the burden of uncorrected refractive error (fig 1). As expected, myopia prevalence was found to be strongly correlated with the rate of uncorrected refractive error (R2 = 0.57, fig 2).

Table 1 Population based studies of uncorrected and undercorrected refractive error.

| Study name, location | Age of subjects | Sample size | Definition of uncorrected refractive error | % uncorrected refractive error | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tehran Eye Study | 5–95 | 6497 | <6/12 in better eye, improve with spectacles | 4.8% | ||

| Refractive Error Study in Children, Sydney | 6 | 1738 | <6/12 in better eye, improve with spectacles | 1.3% | ||

| Bangladesh | 30+ | 11 624 | <6/12 in better eye, improve with spectacles | 10.2% | ||

| Refractive Error Study in Children, Guangzhou, China | 5–15 | 5053 | ⩽6/12 in better eye, improve to 6/10 | 22.3% | ||

| Refractive Error Study in Children, South Africa | 5–15 | 4890 | ⩽6/12 in better eye, improve to 6/10 | 1.4% | ||

| Refractive Error Study in Children, New Delhi | 5–15 | 6447 | ⩽6/12 in better eye, improve to 6/10 | 6.4% | ||

| Refractive Error Study in Children, rural Andhra Pradesh, India | 7–15 | 4074 | ⩽6/12 in better eye, improve to 6/10 | 2.7% | ||

| Projecto VER, Mexican Americans in Arizona, USA | 40+ | 4774 | <6/12 in better eye, improve 2 lines | 6.0% | ||

| Refractive Error Study in Children, Gombak District, Malaysia | 7–154 | 4634 | ⩽6/12 in better eye, improve to 6/10 | 17.1% | ||

| Refractive Error Study in Children, Shunyi District, China | 5–15 | 5884 | ⩽6/12 in better eye, improve to 6/10 | 12.8% | ||

| Refractive Error Study in Children, La Florida, Chile | 5–15 | 5303 | ⩽6/12 in better eye, improve to 6/10 | 15.8% | ||

| Refractive Error Study in Children, Mechi Zone, Nepal | 5–15 | 5067 | ⩽6/12 in better eye, improve to 6/10 | 2.9% | ||

| Visual Impairment Project, Victoria, Australia | 40+ | 4735 | <6/6–2 letters in better eye, improve 1+ lines | 9.8% | ||

| Blue Mountains Eye Study, Australia | 49–97 | 3654 | ⩽6/9 in better eye, improve 2+ lines | 10.2% | ||

| Tanjang Pagar Survey, Singapore | 40–79 | 1232 | 2+ line improvement in either eye | 17.3% | ||

| National Eye Survey, Malaysia | All ages | 18 027 | <6/18 in better eye, improvement | 1.2% | ||

| Andhra Pradesh Eye Disease Study, India | All ages | 2522 | <6/12 in better eye, improvement | 4.3% | ||

| Sumatra, Indonesia | 21+ | 989 | <6/18, improve 2+ lines | 0.7% | ||

| Lebanon | All ages | 10 148 | <6/18, improvement | 1.9% | ||

| South Karachi, Pakistan | 5–15 | 5110 | <6/18, improvement | 2% |

Figure 1 Relation of uncorrected refractive error to per capita gross domestic product, 2003.

Figure 2 Relation of uncorrected refractive error to myopia prevalence.

In addition to providing a global picture of uncorrected refractive error, this review of the published literature revealed some of the challenges facing researchers and policy makers who want to assess the current status of uncorrected refractive error in the world. Firstly, there is no agreed upon terminology, with both “uncorrected refractive error” and “undercorrected refractive error” in common use. Secondly, researchers have used various cut‐off points and levels of improvement after spectacle correction to define uncorrected refractive error. The visual acuity cut‐off point of 6/12 is often chosen because that is the vision required to legally obtain a driver's licence in many countries, and therefore can have a major impact on daily functioning. The visual acuity cut‐off point of 6/18 is usually chosen because it is the World Health Organization criterion for moderate visual impairment.

If myopia is responsible for much of the uncorrected refractive error in the world, then we must consider the epidemiology of myopia to approach the challenge of eliminating vision impairment because of uncorrected refractive error. Heritability of refractive error has been estimated to be as high as 85%.23 Despite the high estimated heritability, environment, particularly near work, has been shown to play an important part in the development of myopia.24,25 Evidence of the relative impact of environment versus genetics is demonstrated through rapid changes in incidence in recent decades. Recent reviews of the epidemiology of myopia reveal that the prevalence and incidence of myopia have been increasing, especially in Asian populations where myopia has reached epidemic proportions. With more than 20% of the world's population residing in China alone, any increase in myopia, and subsequent uncorrected refractive errors, in China will affect the global estimates and ability to meet the Vision 2020 goal to eliminate preventable blindness.

Provision of appropriate spectacles is one of the simplest, most cost effective strategies to improve vision, yet uncorrected refractive error is the primary cause of moderate vision impairment throughout the world. In many countries, a shortage of eye care specialists in rural areas may contribute to the problem.2 What novel strategies have been proposed to address the problem of uncorrected refractive errors? It has been estimated that up to 20% of moderate vision impairment could be eliminated through the availability of affordable, “off the shelf” spectacles for moderate refractive errors.26 This is a simple strategy, yet has not been adopted in any countries to my knowledge. Perhaps a randomised clinical trial would provide sufficient proof for countries to comfortably adopt this strategy to reduce uncorrected refractive error. Adoption could be accomplished in the context of driver's licence renewals to implement screenings and make spectacles available when needed. Annual vision screening of the elderly as a component of annual physical examinations has also been suggested.27 Other culturally specific, age specific, feasible ideas need to be developed and evaluated within each country.

Another area of potential research to accompany the implementation of strategies to reduce uncorrected refractive error is to quantify the impact of this reduction on quality of life and other outcomes, such as road accidents. Research to date has focused primarily on the impact of uncorrectable vision impairment on quality of life and road accidents. These data could provide evidence of the need for ongoing support of programmes to eliminate uncorrected vision impairment.

In summary, uncorrected refractive error is a global challenge that will keep us from meeting the Vision 2020 goal unless changes are made between now and then. Politicians, policy makers, primary care providers, and eye specialists need to work together to develop simple, creative strategies to combat vision impairment caused by uncorrected refractive error. The published data can serve as a baseline to compare the success of future interventions. The time to act boldly is now.

References

- 1.Thylefors B. A global initiative for the elimination of avoidable blindness. Am J Ophthalmol 199812590–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pizzarello L, Abiose A, Ffytche T.et al Vision 2020: the right to sight. A global initiative to eliminate avoidable blindness. Arch Ophthalmol 2004122615–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foster A, Resnikoff S. The impact of Vision 2020 on global blindness. Eye 2005191133–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robaei D, Rose K, Ojaimi E.et al Visual acuity and the causes of visual loss in a population‐based sample of 6‐year‐old Australian children. Ophthalmology 20051121275–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourne R R A, Dineen B P, Huq D M N.et al Correction of refractive error in the adult population of Bangladesh: meeting the unmet need. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200445410–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He M, Zeng J, Liu Y.et al Refractive error and visual impairment in urban children in southern China. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200445793–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naidoo K S, Raghunandan A, Mashige K P.et al Refractive error and visual impairment in African children in South Africa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003443764–3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murthy G V S, Gupta S K, Ellwein L B.et al Refractive error in children in an urban population in New Delhi. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200243623–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dandona R, Dandona L, Srinivas M.et al Refractive error in children in a rural population in India. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200243615–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muñoz B, West S K, Rodriquez J.et al Blindness, visual impairment and the problem of uncorrected refractive error in a Mexican‐American population: Projector VER. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200243608–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goh P ‐ P, Abqariyah Y, Pookhare G P.et al Refractive error and visual impairment in school‐age children in Gombak District, Malaysia. Ophthalmology 2005112678–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao J, Pan X, Sui R.et al Refractive error in children: results from Shunyi District, China. Am J Ophthalmol 2000129427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maul E, Barroso S, Munoz S R.et al Refractive error study in children: results from La Florida, Chile. Am J Ophthalmol 2000129445–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pokharel G P, Negrel A D, Munoz S R.et al Refractive error study in children: results from Mechi Zone, Nepal. Am J Ophthalmol 2000129436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liou H L, McCarty C A, Jin C L.et al prevalence and predictors of undercorrected refractive errors in the Victorian population. Am J Ophthalmol 1999127590–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thiagalingam S, Cumming R G, Mitchell P. Factors associated with undercorrected refractive errors in an older population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol 2002861041–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saw S ‐ M, Foster P J, Gazzard G.et al Undercorrected refractive error in Singaporean Chinese adults. Ophthalmology 20041112168–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zainal M, Ismail S M, Ropilah A R.et al Prevalence of blindness and low vision in Malaysian population: results from the National Eye Survey 1996. Br J Ophthalmol 200286951–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dandona L, Dandona R, Naduvilath T J.et al Burden of moderate visual impairment in an urban population in southern India. Ophthalmology 1999106497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saw S ‐ M, Husain R, Gazzard G M.et al Causes of low vision and blindness in rural Indonesia. Br J Ophthalmol 2003871075–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansour A M, Kassak K, Chaya M.et al National survey of blindness and low vision in Lebanon. Br J Ophthalmol 199781905–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaikh S P, Aziz T M. Pattern of eye diseases in children of 5–15 years at Bazzertaline Area (south Karachi) Pakistan. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 200515291–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammond C J, Snieder H, Gilbert C E.et al Genes and environment in refractive error: the Twin Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001421232–1236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fredrick D R. Myopia. BMJ 20023241195–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saw S ‐ M. A synopsis of the prevalence rates and environmental risk factors for myopia. Clin Exp Optom 200386289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maini R, Weih L A, McCarty C A.et al Correction of refractive error in the Victorian population: the feasibility of “off the shelf” spectacles. Br J Ophthalmol 2001851283–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans B J W, Rowlands G. Correctable visual impairment in older people: a major unmet need. Ophthal Physiol Opt 200424161–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]