Abstract

Aim

To estimate the prevalence and causes of blindness and visual impairment in the population aged 40 years and over in Muyuka, a rural district in the South West Province of Cameroon.

Methods

A multistage cluster random sampling methodology was used to select 20 clusters of 100 people each. In each cluster households were randomly selected and all eligible people had their visual acuity (VA) measured by an ophthalmic nurse. Those with VA <6/18 were examined by an ophthalmologist.

Results

1787 people were examined (response rate 89.3%). The prevalence of binocular blindness was 1.6% (95% CI: 0.8% to 2.4%), 2.2% (1.% to 3.1%) for binocular severe visual impairment, and 6.4% (5.0% to 7.8%) for binocular visual impairment. Cataract was the main cause of blindness (62.1%), severe visual impairment (65.0%), and visual impairment (40.0%). Refractive error was an important cause of severe visual impairment (15.0%) and visual impairment (22.5%). The cataract surgical coverage for people was 55% at the <3/60 level and 33% at the <6/60 level. 64.3% of eyes operated for cataract had poor visual outcome (presenting VA<6/60).

Conclusions

Strategies should be developed to make cataract services affordable and accessible to the population in the rural areas. There is an urgent need to improve the outcome of cataract surgery. Refractive error services should be provided at the community level.

Keywords: blindness, Cameroon, survey, cataract, prevalence

There are 161 million people with visual impairment in the world, of whom approximately 37 million are blind. Global estimates suggest that cataract is the leading cause of blindness, responsible for half of blindness.1 Cataract blindness is increasing in Africa and Asia, owing to the growing number of elderly people and lack of services to tackle the disease appropriately.1,2,3

“Vision 2020—the right to sight” was launched in 1999 to eliminate avoidable blindness by the year 2020 through implementing national and district action plans. Baseline data on the prevalence and causes of blindness and visual impairment are needed for the planning and monitoring of Vision 2020 programmes, but these data are often not available.

There has been no nationwide survey of blindness in Cameroon. A population based blindness survey was conducted in an arid area in the far north of Cameroon.4 Other available data on blindness in Cameroon have been generated through screening,5 and from population based surveys in neighbouring countries.6,7,8,9

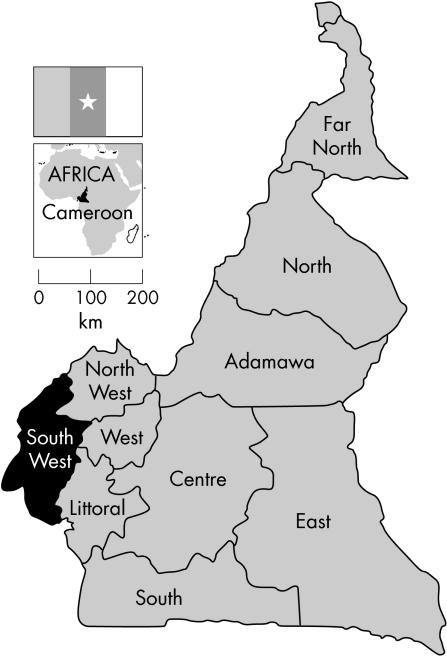

The South West Province of Cameroon is an agricultural area with an equatorial rain forest ecosystem. The province is hyperendemic for onchocerciasis and community directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI) is in place and a Vision 2020 action plan was launched in 2001. Muyuka Health District is a rural area in this province (figs 1 and 2), with an estimated population of 75 000 (approximately 13 000 aged ⩾40 years).10,11

Figure 1 The provinces of Cameroon.

Figure 2 Eye units in Cameroon's South West Province (May 2005).

The aim of this survey is to conduct a rapid assessment of cataract surgical services (RACSS) to determine the prevalence and causes of blindness and visual impairment and the availability of cataract surgical services in people aged ⩾40 years in Muyuka Health District.12,13,14,15,16 This information will be used to facilitate planning for the South West Province Eye Care Programme.

Methods

Study design

A population based cross sectional survey was conducted on people aged 40 years and above. The sample was selected through multistage cluster random sampling with probability proportional to size.

Sampling procedure

A sampling frame consisting of the list of all health areas' villages with their population was obtained from the Ministry of Health. The population aged ⩾40 years was estimated from the updated 1987 census.10,11 The expected prevalence of blindness was 3.2%, based on the prevalence estimate from a similar area in Nigeria.7 A precision of 30%, a design effect of 1.5 (based on unpublished data from Kenya), and confidence of 95% were used in the sample size calculation. The minimum required sample size was 1700 and this was increased to 1955 to account for 15% non‐response (using Epi‐Info 6.04). The sampling frame selected clusters which were groups of 100 people. In total, 20 clusters of 100 people each were required for the survey.

Muyuka Health District consists of five health areas. In four areas the villages for the clusters were selected through probability proportionate to size sampling.12,13,14,15,16 In the fifth area, the villages' population size was not available and clusters were selected through simple random sampling. Once the villages for the clusters had been selected, all eligible people (that is, those aged ⩾40 years who had lived in the area for ⩾6 months) were enumerated by trained community directed distributors of ivermectin. Households to be examined were randomly selected by spinning a bottle at one end of the village to choose which side of the village to start and sampling consecutive households. All eligible people living in selected households were examined until the cluster size of 100 was obtained. Absentees were revisited up to two times, once on the same day in the evening and then the following day, early in the morning.

Data collection

Data collection consisted of two parts: the questionnaire and the ocular examination. Demographic information was collected. All participants had their distance presenting visual acuity (VA) measured in front of their door, using a 6 metre illiterate Snellen's acuity chart. A good reading consisted of four correct consecutive showings, or five correct out of six showings. Pinhole vision was measured for those with VA <6/18 in either eye. For aphakic cases, a +10 dioptre pair of glasses was used. If presenting VA was <6/18 in either eye but improved to VA ⩾6/18 aided (pinhole or +10 glasses), an ocular examination using a penlight and magnification and fundus examination with a direct ophthalmoscope was performed with a non‐dilated pupil. If VA did not improve to 6/18 after correction, the fundus examination was performed with a dilated pupil. The ocular examination was performed by the ophthalmologist in the participant's house in a shaded room.

Cases with operable cataract (<6/60 vision as a result of cataract) were asked why they had not gone for cataract surgery. A maximum of four reasons were allowed.

Study definitions

The following definitions were used for the purpose of this survey.

Blindness: presenting VA <3/60 in the better eye with available correction.

Severe visual impairment: presenting VA <6/60 but ⩾3/60 in the better eye with available correction.

Visual impairment: presenting VA <6/18 but ⩾6/60 in the better eye with available correction.

Cataract: lens opacity obscuring at least half of red reflex.17

Refractive error: improvement of unaided VA <6/18 to VA ⩾6/18 using pinhole or +10 dioptre glasses for aphakia.

Onchocerciasis: characteristic onchocercal sclerosing keratitis; or presence of characteristic onchocercal chorioretinitis with or without optic atrophy; or optic atrophy with pigmentary lesions around the disc.

Survey team

The survey team consisted of one ophthalmologist, one senior primary healthcare nurse, three experienced ophthalmic nurses, one refractionist, one guide, and one driver. One day of training was organised to orient the team members in the use of the survey questionnaire and procedures. The accuracy of visual acuity screening by the nurses was satisfactory when compared to the ophthalmologist (the gold standard).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis consisted of frequency analysis, bivariate analysis using tables and χ2 test for statistical significance, stratified analysis using Mantel‐Haenszel test, and multivariate logistic regression. Confidence intervals and design effects were calculated using the CSample table of Epi‐Info 6.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the survey was obtained from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the Provincial Delegation for Public Health in the South West Province. The communities were informed of the proposed survey and informed oral consent was obtained from the community. Detailed information was given to individual participants and oral consent was obtained for the examination. Confidentiality and anonymity were preserved during data collection, analysis, and reporting. All cases with eye problems were either treated on the spot with free eye medications or were referred for free further consultation or free/subsidised eye surgery, as appropriate. Reading glasses were sold in the community at subsidised hospital prices.

Results

In all, 1787 out of the 2000 selected subjects were examined, giving a response rate of 89.3%. Out of the 213 (10.7%) non‐respondents, 192 (9.6%) subjects were absent, 15 (0.8%) refused to participate, three (0.2%) could not be examined, and three died between enumeration and examination (0.2%). Non‐respondents were of similar age, sex, and occupation as respondents. A total of 903 males (50.5%) and 884 females (49.5%) were examined (table 1). The majority of respondents were farmers (45.0%) or housewives (24.3%). The sample had a similar age and sex distribution as the district population (table 1).

Table 1 Age and sex distribution of sample and district population.

| Age (years) | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | District | Sample | District | |

| 40–49 | 385 (42.6%) | 2789 (44.3%) | 412 (46.6%) | 2804 (41.8%) |

| 50–59 | 241 (26.7%) | 1828 (29.0%) | 211 (23.9%) | 1949 (29.0%) |

| 60–69 | 158 (17.5%) | 1074 (17.1%) | 148 (16.7%) | 1226 (18.3%) |

| ⩾70 | 119 (13.2%) | 608 (9.7%) | 113 (12.8%) | 734 (10.9%) |

| Total | 903 | 6299 | 884 | 6713 |

Presenting visual acuity

The prevalence of blindness was 1.6% (95% CI: 0.8% to 2.4%; design effect = 1.8), severe visual impairment was 2.2% (95% CI: 1.4% to 3.1%; design effect = 1.6) and visual impairment was 6.4% (95% CI: 5.0–7.8%; design effect = 1.5) (table 2). The age and sex standardised prevalence of blindness was 1.4% (95% CI: 0.9% to 2.0%). The prevalence of blindness and severe visual impairment was similar in men and women, but women were significantly more likely to be visually impaired (p = 0.006). The prevalence of cataract blindness was 0.9% (95% CI: 0.4% to 1.4%; design effect = 1.5), cataract severe visual impairment was 1.3% (95% CI: 0.8% to 1.8%; design effect = 0.8), and cataract visual impairment was 2.3% (95% CI: 1.9% to 2.7%; design effect = 0.4). Seven people had unilateral or bilateral aphakia and 15 had unilateral or bilateral pseudophakia, giving a prevalence of aphakia or pseudophakia of 1.2% (95% CI: 0.7% to 1.7%).

Table 2 Distribution of survey visual acuity results by VA category and sex in Muyuka district.

| VA with available correction | Males (n = 903) | Females (n = 884) | Total (n = 1787) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VA <3/60 | |||

| Bilateral blindness | 16 (1.8%) | 13 (1.5%) | 29 (1.6%) |

| Unilateral blindness | 75 (8.3%) | 53 (6.0%) | 128 (7.2%) |

| Blind eyes | 107 (11.8 %) | 79 (8.9%) | 186 (10.4%) |

| VA <6/60–⩾3/60 | |||

| Bilateral severe visual impairment | 18 (2.0%) | 22 (2.5%) | 40 (2.2%) |

| Unilateral severe visual impairment | 17 (1.9%) | 20 (2.3%) | 37 (2.1%) |

| Severely visually impaired eyes | 53 (5.9%) | 64 (7.2%) | 117 (6.5%) |

| VA <6/18–⩾6/60 | |||

| Bilateral visual impairment | 44 (4.9%) | 71 (8.0%) | 115 (6.4%) |

| Unilateral visual impairment | 33 (3.6%) | 35 (3.9%) | 68 (3.8%) |

| Visually impaired eyes | 121 (13.4%) | 177 (20.0%) | 298 (16.7%) |

| Aphakia/pseudophakia | |||

| Bilateral aphakia/pseudophakia | 4 (0.4%) | 2 (0.2%) | 6 (0.3%) |

| Unilateral aphakia/pseudophakia | 11 (1.2%) | 5 (0.6%) | 16 (0.9%) |

| Aphakic/pseudophakic eyes | 19 (2.1%) | 9 (1.0%) | 28 (1.6%) |

Demographic distribution of blindness

The multivariate logistic regression model showed that visual loss increased with 10 year age group—blindness (OR = 4.0, 95% CI: 2.5 to 5.1), severe visual impairment (OR = 3.8, 95% CI: 2.8 to 5.1), and visual impairment (OR = 2.5, 95% CI: 2.1 to 3.0). Blindness, severe visual impairment, and visual impairment were more prevalent in people with no occupation (12.2%, 7.0%, and 22.4%, respectively) than in farmers (2.9%, 6.8%, and 1.9%, respectively).

Causes of blindness and visual impairment

Cataract was the most important cause of blindness (62.1%), severe visual impairment (65.0%), and visual impairment (40.0%) (table 3). Onchocerciasis was also a leading cause of blindness (13.8%) and severe visual impairment (12.5%). Refractive error was an important cause of visual impairment (26.1%) and severe visual impairment (15.0%), but not blindness. Overall, avoidable causes of blindness (that is, uncorrected and corrected cataract, refractive error, onchocerciasis, and corneal scar) made up 82.8% of blindness, 95.0% of severe visual impairment, and 69.6% of visual impairment.

Table 3 Distribution of main causes of binocular blindness, severe visual impairment, and visual impairment.

| Cause | Blindness (VA<3/60) | Severe visual impairment (VA<6/60–⩾3/60) | Visual impairment (VA<6/18–⩾6/60) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 29) | (n = 40) | (n = 115) | |

| Cataract | 18 (62.1%) | 26 (65.0%) | 46 (40.0%) |

| Onchocerciasis | 4 (13.8%) | 5 (12.5%) | 4 (3.5%) |

| Posterior segment diseases | 4 (13.8%) | 1 (2.5%) | 32 (27.8%) |

| Refractive error | 0 | 6 (15.0%) | 30 (26.1%) |

| Surgery related | 0 | 1 (2.5%) | 0 |

| Phthisis/no globe | 2 (6.9%) | 0 | 0 |

| Others | 1 (3.5%) | 1 (2.5%) | 3 (2.6%) |

| Avoidable* | 24 (82.8%) | 38 (95.0%) | 80 (69.6%) |

*Cataract (corrected and uncorrected), refractive error, onchocerciasis, corneal scar.

Cataract surgery

The cataract surgical coverage (CSC) was the number of aphakic/pseudophakic people (or eyes) divided by the number who had operable cataract (that is, number aphakic/pseudophakic plus the number needing surgery). The CSC for people was 55% (22/18 + 22) at <3/60 level and 33% (22/44 + 22) at the <6/60 level. The majority of cases (67.9%) had received an intraocular lens implant.

Only 25% of eyes operated for cataract had good postoperative outcome (VA ⩾6/18), 10.7% had borderline outcome (VA <6/18 and ⩾6/60), and 64.3% poor outcome (VA <6/60) (table 4). Outcomes were better for the people who had surgery with an intraocular lens. Patients with good outcome were on average younger (mean 66 years) than those with a borderline (77 years) or poor outcome (74 years).

Table 4 Presenting visual outcome after cataract surgery.

| Procedure | Visual outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Borderline | Poor | |

| ICCE | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 8 (88.9%) |

| IOL | 6 (31.6%) | 3 (15.8%) | 10 (52.6%) |

| Total | 7 (25.0%) | 3 (10.7%) | 18 (64.3%) |

ICCE, intracapsular cataract extraction; IOL, intraocular lens.

The most common reasons for not going for surgery among the 156 responders was lack of awareness of cataract (33.3%), inability to pay (30.1%), and a feeling they could cope with the cataract (9.6%).

Discussion

The prevalence of bilateral blindness in the sample population aged over 40 years was 1.6%. Cataract was the most important cause of blindness, accounting for 62.1% of cases. Refractive error was an important cause of severe visual impairment (15.0%) and visual impairment (26.1%). Overall, avoidable causes of blindness (that is, uncorrected and corrected cataract, refractive error, onchocerciasis, corneal scar) made up the vast majority of cases of blindness (82.8%), severe visual impairment (95.0%), and visual impairment (69.6%). The coverage of cataract surgery was low and the quality of surgery was of concern as 64.3% of those operated for cataract had poor postoperative outcome, including more than half of those who had an intraocular lens implanted.

Our study found a lower prevalence of blindness than expected, based on a survey in a similar area in Nigeria,7 and the global estimates for Africa.1 Previous prevalence of blindness surveys used different age groups, making them difficult to compare. However, a higher prevalence of blindness was found in surveys in the extreme north Cameroon,4 northern Nigeria,6 southern Malawi,18 and Central African Republic,19 and a lower prevalence of blindness in Wengi District, Ghana,20 Benin,21 and Congo.22 The low prevalence of blindness in the study area could be explained by the absence of trachoma and the decline of onchocerciasis as a result of the CDTI control programme.

Cataract was the dominant cause of blindness, as in many other studies in sub‐Saharan Africa.1,4,7,22,23,24 Onchocerciasis was the second cause of blindness in our study, as in other onchoendemic areas.7,20 Studies that used presenting VA, rather than best corrected VA, confirm our finding that refractive error is an important cause of visual impairment.4,20 Our study found old age and having no occupation as risk factors for blindness, severe visual impairment, and blindness, which is in accordance with similar studies.23,24,25,26,27

There were a number of limitations to the study. The population of the survey area was substantially smaller than recommended for the RACSS; however, this was the population size that could reasonably be sampled given the time and resource constraints. Enumeration was not complete in all clusters, because some villages or quarters had a relatively large population size (4000–10 000 inhabitants). In villages with incomplete enumeration, the survey team had to carry out enumeration and examination at the same time. A considerable number of old people did not know their age and did not have identification cards. An estimate was made of their age from their physical appearance and age verification based on approximation of age at the time of key sociopolitical events. The age distribution of the sample was somewhat older than the age distribution for the district and this may have overestimated the prevalence of blindness in the sample, although the population data for the district may not be reliable as they were extrapolated from the 1987 census data. As a result of the practical difficulties of diagnosing glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and age related macular degeneration under field conditions, these disorders were classified together as “posterior segment disease.”

The study also had strengths. The response rate was high.12 The age, sex, and occupation distribution of the respondents and non‐respondents were similar, and the age and sex distribution of the sample and district population were similar, indicating a low potential for selection bias. Only one team with one ophthalmologist and experienced nurses applying a standardised procedure collected data, and interobserver agreement was good.

In conclusion, while a similar survey is needed for the urban area, stakeholders of the South West Province Comprehensive Eye Care should develop strategies to make high volume/high quality cataract services affordable and accessible to the population in order to reduce the prevalence of visual impairment from cataract. They should also focus on providing refractive error services at community level.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the International Centre for Eye Health (ICEH), LSHTM, for their technical and financial support, and to Sight Savers International Cameroon for their logistic support. Our appreciation goes to Dr Mafany Njie Martin, the provincial delegate for health in the South West Province, Cameroon, for authorising the survey and his staff, Mr Emmanuel Fombon, Ms Geneva Williams, Ms Goretti Zinkeng, and Mr Francis Nguatem for field work.

Abbreviations

CDTI - community directed treatment with ivermectin

CSC - cataract surgical coverage

RACSS - rapid assessment of cataract surgical services

VA - visual acuity

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya'ale D.et al Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull World Health Organ 200482844–851. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster A, Johnson G. Blindness in the developing world. Br J Ophthalmol 199377398–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewallen S, Courtright P. Blindness in Africa: present situation and future needs. Br J Ophthalmol 200185897–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson M R, Mansour M, Ross‐Degnan D.et al Prevalence and causes of low vision and blindness in the extreme north province of Cameroon, West Africa.Ophthalmic Epidemiol 1996323–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabe Tambi F. Causes of blindness in the western province of Cameroon.Rev Int Trach Pathol Ocul Trop Subtrop Sante Publique 199370185–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abiose A, Murdoch I, Babalola O.et al Distribution and aetiology of blindness and visual impairment in mesoendemic onchocercal communities, Kaduna State, Nigeria. Kaduna Collaboration for Research on Onchocerciasis.Br J Ophthalmol 1994788–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adeoye A. Survey of blindness in rural communities of south‐western Nigeria.Trop Med Int Health 19961672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ezepue U F. Magnitude and causes of blindness and low vision in Anambra State of Nigeria (results of 1992 point prevalence survey).Public Health 1997111305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kayembe D L, Kasonga D L, Kayembe P K.et al Profile of eye lesions and vision loss: a cross‐sectional study in Lusambo, a forest‐savanna area hyperendemic for onchocerciasis in the Democratic Republic of Congo.Trop Med Int Health 2003883–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United States Census Bureau International data base summary demographic data for Cameroon. International Data Base 2005

- 11.United Nations Development Programme Human development indicators for Cameroon. UNDP 2003

- 12.World Health Organization Rapid assessment of cataract surgical services. WHO/PBL 2001: 01, 84. Geneva: WHO

- 13.Haider S, Hussain A, Limburg H. Cataract blindness in Chakwal District, Pakistan: results of a survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 200310249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duerksen R, Limburg H, Carron J E.et al Cataract blindness in Paraguay—results of a national survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 200310349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amansakhatov S, Volokhovskaya Z P, Afanasyeva A N.et al Cataract blindness in Turkmenistan: results of a national survey. Br J Ophthalmol 2002861207–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pongo Aguila L, Carrion R, Luna W.et al Cataract blindness in people 50 years old or older in a semirural area of northern Peru. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 200517387–393. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Mehra V, Minassian D C. A rapid method of grading cataract in epidemiological studies and eye surveys.Br J Ophthalmol 198872801–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chirambo M C, Tielsch J M, West K P., Jret al Blindness and visual impairment in southern Malawi.Bull World Health Organ 198664567–572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz E C, Huss R, Hopkins A.et al Blindness and visual impairment in a region endemic for onchocerciasis in the Central African Republic.Br J Ophthalmol 199781443–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moll A C, van der Linden A J, Hogeweg M.et al Prevalence of blindness and low vision of people over 30 years in the Wenchi District, Ghana, in relation to eye care programmes.Br J Ophthalmol 199478275–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Negrel A D, Avognon Z, Minassian D C.et al Blindness in Benin.Med Trop (Mars) 199555409–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Negrel A D, Massembo‐Yako B, Botaka E.et al Prevalence and causes of blindness in the Congo.Bull World Health Organ 199068237–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faal H, Minassian D, Sowa S.et al National survey of blindness and low vision in the Gambia: results.Br J Ophthalmol 19897382–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dineen B P, Bourne R R, Ali S M.et al Prevalence and causes of blindness and visual impairment in Bangladeshi adults: results of the National Blindness and Low Vision Survey of Bangladesh.Br J Ophthalmol 200387820–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dandona R, Dandona L. Socioeconomic status and blindness.Br J Ophthalmol 2001851484–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson G J, Foster A. Prevalence, incidence and distribution of visual impairment. In: Johnson GJ, Minassian DC, Weale RA, et al, eds. The epidemiology of eye disease. 2nd ed. London: Arnold, 200313–28. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abou‐Gareeb I, Lewallen S, Bassett K.et al Gender and blindness: a meta‐analysis of population‐based prevalence surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2001839–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]