Abstract

Retinal vein occlusions (RVO) are the second commonest sight threatening vascular disorder. Despite its frequency treatments for RVO are unsatisfactory and include several that have not been tested by large, well designed, prospective, randomised controlled trials. There is also the lack of long term follow up in many of the available small uncontrolled studies, and the timings of interventions are haphazard. This review aims to evaluate the current knowledge relating to the pathogenesis, suggested treatments for the different types of RVO, and their complications. Isovolaemic haemodilution is of limited benefit and should be avoided in patients with concurrent cardiovascular, renal, or pulmonary morbidity. Evidence to date does not support any therapeutic benefit from radial optic neurotomy, optic nerve decompression, or arteriovenous crossing sheathotomy on its own. Vitrectomy combined with intravenous thrombolysis may offer promise for central RVO. Similarly, vitrectomy combined with arteriovenous sheathotomy intravenous tissue plasminogen activator may offer benefits for branch RVO. RVOs occur at significantly high frequency to allow future prospective randomised controlled studies to be conducted to evaluate the role of different therapeutic modalities singly or in combination.

Keywords: retinal vein occlusion, steroids

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) is the second most common retinal vascular disorder after diabetic retinopathy and is a significant cause of visual handicap.1,2,3,4 The prevalence of retinal vein occlusions has been shown to vary from 0.7% to 1.6%.5 In the United Kingdom retinal vein occlusions are responsible for a significant number of new blind registrations per annum and eye enucleations subsequent to neovascular complications.

There are two main types of retinal vein occlusion—central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) and branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO). Our knowledge of the outcome of patients with CRVO and BRVO has been enhanced by the findings of the Central Vein Occlusion Study (CVOS)3 and the Branch Vein Occlusion Study groups (BVOS).1,6

According to the CVOS, the final visual acuity after CRVO depends on the visual acuity at presentation. Vision did not improve in 80% patients with vision less than 6/60 (20/200) at presentation but 65% of patients with vision better than 6/12 (20/40) maintained this level of acuity at the end of follow up.3

The visual prognosis following CRVO is largely related to the residual level of venous perfusion. In ischaemic (non‐perfused) CRVO the final visual acuity is 3/60 (20/400) or worse in 87% of cases, whereas for non‐ischaemic cases the vision is 6/9 (20/30) or better in 57%.7 Additionally, the subsequent development of macular oedema and neovascularisation has adverse effects on vision. Panretinal laser photocoagulation helps to reduce the progress of neovascular complications. However, the use of grid macular laser photocoagulation to reduce macular oedema has not been found to improve visual acuity in patients with persistent macular oedema.3,6,8

BRVO is more common than CRVO and has a more favourable prognosis. The BVOS reported that, overall, 50–60% patients with BRVO will maintain visual acuity of 6/12 (20/40) or better after 1 year and thereafter the natural course of BRVO remains relatively static.2

Visual loss following BRVO may result from macular oedema, foveal haemorrhage, vitreous haemorrhage, epiretinal membrane, retinal detachment, macular ischaemia, and neovascular complications. The BVOS demonstrated that the probability for retinal neovascularisation is significantly greater in eyes with an area of retinal non‐perfusion that measures 5 disc diameters or more and that the use of laser photocoagulation is beneficial for patients who develop macular oedema or retinal neovascularisation and have visual acuities of 20/40 to 20/100.9

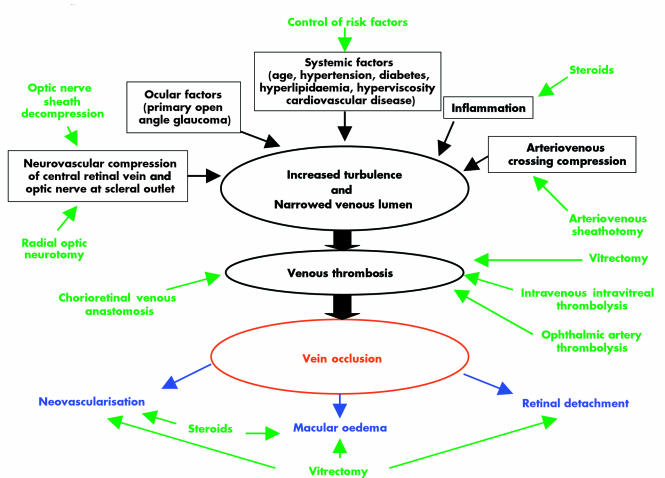

Until recently, the management of vein occlusions has been largely dependent on the results of the CVOS and BVOS. Patients are investigated to exclude any underlying systemic or ocular risk factors and treatment is given for sight threatening sequelae. However, over the past decade more interventional therapeutic options have emerged. The new treatments are targeted at the presumed underlying mechanical and physiological factors that lead to venous occlusion (fig 1).

Figure 1 Outline of current treatments for RVO. Treatment modalities indicated in green, possible aetiological factors and mechanisms indicated in black/red, and complications of vein occlusion indicated in blue.

This review aims to put into perspective the emerging treatment options for both CRVO and BRVO and discuss whether they offer a beneficial alternative over the natural course of the disease (tables 1 and 2). A summary of the main studies described in the literature is given in tables 3 and 4.

Table 1 Summary of interventional methods for central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO).

| Interventions for CRVO |

|---|

| Steroids |

| • Thrombolysis |

| • intravitreal thrombolysis |

| • retinal venous thrombolysis |

| • ophthalmic artery thrombolysis |

| Isovolaemic haemodilution |

| Radial optic neurotomy |

| Chorioretinal anastamosis |

| Optic nerve sheath decompression |

| Lamina puncture (experimental) |

Table 2 Summary of interventional methods for branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO).

| Interventions for BRVO |

|---|

| Steroids |

| Isovolaemic haemodilution |

| Vitrectomy |

| Arteriovenous crossing sheathotomy |

| Chorioretinal anastomosis |

Table 3 Summarising treatment modalities for BRVO.

| Reference | Type of vein occlusion ischaemic or non‐ischaemic | Study type | No of patients and follow up | Visual outcome | Complications and comments | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arteriovenous crossing sheathotomy and vitrectomy | |||||||||||||

| Osterloh and Charles73 | BRVO (perfusion status unknown) | Case report | 1 patient, 8 months follow up | 54 year old female, VA improved from 20/200 to 20/25 | 3 week history of BRVO | ||||||||

| Opremcak and Bruce74 | BRVO where VA ↓ secondary to macular haemorrhage and oedema + ischaemia | Prospective non‐randomised | 15 patients, 5 months follow up (range 1–12 months) | Initial VA ⩽ 20/70, Snellen VA equal or better in 12 of 15 patients (80%),10/15 patients (67%) had improved postoperative VA with average of 4 lines vision gained (range 1–9 lines). 3 patients had worse VA with average 2 lines vision lost. 2 patients had surgical success and resolution of retinal haemorrhage and oedema but no VA improvement | Retinal vascular bleeding in 2 patients, needed needle diathermy (these patients had different anatomical configuration, venule underlying bifurcation of arteriole)Can cause NFL defect bleeding. Retinal detachment. Retinal tear, duration of visual symptoms 1–12 months (average 3.3 months) | ||||||||

| Shah et al77 | BRVO with macular oedema | Case reports | 5 patients 6.5 years follow up(range 5–7 years) | Initial VA < 20/200. In 4 out of 5 eyes (80%) VA improved to 20/30–20/70 in 1 eye, VA remained CF secondary to macular ischaemia | Cataract. Vitreous haemorrhage in 2/3 patients, BRVO duration 3–4 weeks | ||||||||

| Le Rouic et al80 | BRVO: recent onset | Prospective | 3 patients, 1 year follow up | Initial VA:20/80 after 11/12 20/80 secondary to ischaemia had laser20/80 after 10/12 20/200 secondary ischaemia had laser20/200 after 9/12 20/200 had persistent macular oedemaNo benefit | |||||||||

| Mester and Dillinger75 | BRVO | Control v case non‐randomised | 43 patients, 23 controls 6 weeks follow up | VA ⩽ 20/50 and macular haemorrhages + oedema or ischaemia. Mean VA ↑ from 0.16 (±0.12) to 0.35 (±0.25) following surgery26 patients (60%) gained at least 2 lines of VA and 12 patients (28%) gained 4 + lines VA. Only 1 patient lost 2 lines VA. All patients with improvement of 4+ lines had incomplete vein occlusion on FFA. 4 eyes with complete occlusion had worst results functionally. Macular oedema + intraretinal haemorrhage resorbed in all patients.Control group:VA ↓ from 0.23 (±0.12) to 022 (±0.16) over 6 weeks5 eyes (20%) gained 2 + lines VA9 patients (36%) lost 2 + linesOperated patients had slightly better functional outcome | Nil, All patients had isovoluaemic haemodilution for 10 days. Occluded vein decompressed in all cases but complete capillary reperfusion seen in only in 4 eyesLongest preop duration of BRVO was 3/12 | ||||||||

| Cahill et al79 | BRVO | Retrospective | 27 patients | 29.6% had resolution of CMO and significant increase in VA. There was no improvement in VA in 2/3 eyes | |||||||||

| Intravitreal triamcinolone | |||||||||||||

| Jonas et al26 | BRVO | Prospective comparative, non‐randomised | 10 patients, 18 controls, 8 months follow up | Mean VA increased significantly in the treated group. 90% of eyes gained VA and 60% had an increase in VA of at least 2 lines | VA increased significantly only in the non‐ischaemic subgroup | ||||||||

| Isovolaemic haemodilution | |||||||||||||

| Chen et al43 | BRVO | Randomised controlled trial | 18 patients, 16 controls, 1 year follow up | Final VA was better in the treated group. Final VA was 6/12 in treated and 6/24 in controls | |||||||||

Table 4 Summarising treatment modalities for CRVO.

| Reference | Type of vein occlusion | Study type | No of patients and follow up | Visual outcome (visual acuity – VA) | Complications and comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic steroids | |||||||

| Shaikh et al11 | Non‐ischaemic CRVO | Case reports | 2 patients | Event in second eye. Patient seen 5/12 post‐CRVO. 1/7 post IV methylpred: VA ↑ to 20/250 from CF1/52 later VA ↑ 20/253/12 later VA ↓ to 20/4003 years later VA 20/200Periocular steroid improved VA to 20/30 initially (in past)Initial VA 20/20 RE and 20/80 LE60 mg pred: VA 20/40 LE at 10 days8/12 later VA 20/80 againRepeat steroid by mouth: VA ↑ to 20/602/12 later: more CMO + ↓ VA now refractory to steroid | NilTransient response1 year hx of CRVO | ||

| Intravitreal steroids | |||||||

| Greenberg et al13 | Haemorrhagic CRVO in 2nd affected eye with macular oedema | Case report | 1 patient | Initial VA 20/400 LE, CF Re (LE has acute visual loss). VA 20/80 in LE 6/52 post‐injection and 20/30 after 3/12. But ↓ VA 6/12 post procedure however macular oedema ↓ 2nd triamcinolone injection VA 20/50 1/12 later. Macular oedema resolved after each injection (shown by OCT)Note: no effect of triamcinolone on fellow eye with longstanding CRVO | Nil↑ IOP (25% eyes)CataractRetinal detachment, endophthalmitis. FFA showed no ischaemia initially. Rarely Rx may be necessary for visual improvement before longstanding macular oedema causes irreversible photoreceptor damage | ||

| Ip et al15 | Non‐ischaemic CRVO | Case report | 1 patient,16 months follow up | 10 months hx of ↓ VA.Initial VA 20/40 in RE VA fell to 20/200 when injection given1 month later VA ↑to 20/25 with resolution of macular oedema | Nil4 mg triamcinolone acetonide | ||

| Ip et al15 | Ischaemic CRVO | Case report | 1 patient,8 months follow up | 8 months hx of CRVO3/52 post‐injection, VA ↑ from 20/200 to 20/100 with ↓ macular oedema3/12 post injection VA ↓ to 20/400 | NilTemporary benefit in ischaemic CRVOVA improvement less marked | ||

| Jonas et al16 | Bilateral CRVO with longstanding macular oedema | Case report | 1 patient,4 months RE follow up6 weeks LE follow up | RE: VA ↑ from 0.05 to 0.25LE: VA ↑ from 0.125 to 0.25Reduced leakage at macula on FFA | NilRE, CRVO 2 years ago; LE, CRVO 1.5 years ago25 mg triamcinolone into each eye 10/52 apart | ||

| Intravenous thrombolysis | |||||||

| Kohner et al29 | CRVO less than 7 days | 20 patients,1 year follow up | VA not significantly different between Rx + control groups | Neovascular glaucoma (1 treated patient) (4 control patients). Vitreous haemorrhage (within 3/7 in 3 treated eyes; within 1 month in 4 control eyes, pre‐vitrectomy era) | |||

| Elman et al30 | CRVO (perfused) | Pilot study (for future randomised controlled trial) | 96 patients,6 months follow up | 42% (n = 89) gained 3 + lines of vision. 37% remained stable. 21% lost 3+ lines. In eyes with 20/100 or worse pre‐Rx vision (n = 32). 59% gained 3+ lines (average gain 6.4 lines). 31% stable. 4% lost 3+ lines | 3 patients developed intraocular bleeding. GI bleeding (1 patient). Fatal CVA (1 patient). Oozing from previous venepuncture sites or slight bruises (all patients). Inferior subretinal PE haemorrhage (1 patient). Vitreous.haemorrhage with retinal detachment (1 patient). Haemorrhagic sub‐RPE detachment (1 patient).<6/12 duration of CRVOt‐PA + aspirint‐PA + aspirin + heparint‐PA + aspirin + heparin + warfarin | ||

| Intravitreal t‐PA | |||||||

| Lahey et al31 | CRVO | Prospective with no control group | 26 patientsCRVO = 23 patientsHemiretinal vein occlusion = 3 patients,6 months follow up | CRVO: VA improved in 7/23 patients (30.4%) at 6 weeks and 8/23 (34.8%) at 6 months | ↑ in macular oedemavitreous haemorrhage1↑ in size of macular haemorrhage2 | ||

| Glacet‐ Bernard et al32 | 15 patients,5–21 months (mean 8 months) follow up | VA ↑ to 20/30 + in 5 eyes (36%) including 2 with complete recovery. VA worse than 20/200 in 3 eyes (28%). Initial VA ⩽ 20/40. At end: 5 (36%) eyes had VA ⩾ 20/30; 5 (36%) had VA 20/200 to 20/30, and 4 (28%) had <20/200 | Nil | ||||

| Recent onset CRVO (1–21 days duration mean 8 days). 75‐ 100 μg t‐PA + low dose heparin | |||||||

| Elman et al34 | CRVO (perfused on FFA) | Prospective non‐comparative case series | 9 patients,>6 months follow up | 4/9 eyes (44%) had 3 + lines improvement at 6 months (average improvement 7 lines). 2 eyes had 6 or more lines loss of vision at 6 months. 3 eyes needed PRP | PRP, 3 eyes for neovascularisation100 μg t‐PA1 baby aspirint‐PA within 2 weeks of symptoms | ||

| Ghazi et al35 | CRVO | Prospective non‐controlled study | 12 patients | 55% of patients with initial VA < 20/200 had a final visual acuity of 20/50 or better | Symptom duration was <3 days | ||

| t‐PA into retinal vein | |||||||

| Weiss and Bynoe37 | CRVO | Prospective non‐comparative interventional case series | 28 patients,11.8 months follow up(range 3–24 months) | VA 20/400 or worse. 22 of 28 patients (79%) experienced at least 1 line of visual improvementInitial VA ⩽20/40015 eyes (54%) – 3 + line ↑ in VA in 3/1214 eyes (40%) had 3 + line ↑ VA by end of follow up10 eyes (36%) ↑ at least 5 lines5 eyes ↑ by at least 8 lines1 eye recovered from 20/400 preop to 20/20 post‐op | |||

| Ophthalmic artery fibrinolysis | |||||||

| Paques et al39 | CRVO + CRAO | Retrospective | 26 patientsCRVO + CRAO : 9 patientsCRVO + cilioretinal AO: 3 patientsCRVO only: 14 patients,10 months follow uprange 2–24 months | Initial VA <20/60 or CRVO in fellow eye or ↓ VA after initial improvement and if other eye lost. 6 patients had ↑ in VA within 48 hours – 4 for these were CRAO + CRVO (in latter, VA was ⩾20/50) | Unable to catheterise vein in 1 patient. ↓ of vision after initial improvement. Intravitreal haemorrhage (2 patients). Mean duration of symptoms 26 days (range 12 hours to 7 months)Urokinase into ophthalmic artery | ||

| Vallee et al46 | Severe non‐ischaemic CRVO | Prospective no control group | 13 patients,1 year follow up | 5/13 patients had ↑ VA + retinal perfusion in 24–48 hours VA returned to normal in 24–48 hours in 3 patients, within 1 week in 1 patient + 1/12 in 1 patient. 1 patient relapsed 1/12 later (repeat CRVO when heparin stopped)At end of follow up 1 had normal vision, 7 had no improvement | Stopping aspirin led to ↓ VA to 20/200 due to macular oedema. Visual loss <30 days + urokinase VA , 20/200 IV heparin 48 hours1000 Mw heparin 1 month, oral aspirin 3 months | ||

| Vallee et al41 | CRAO + CRVO | Prospective | 11 patients,6 years follow up | 7 of 11 patients had slight ↑ in mean VA (p = 0.006)) and then remained stable throughout follow up (p>0.1) not significant | 1 patient, intravitreal haemorrhage, needing vitrectomy and PRP leading to NPL vision. Visual loss 12–72 hours (mean 32.5 hours), except 1 patient treated after 10 days for compassionate reasons. Urokinase | ||

| Radial optic neurotomy | |||||||

| Opremcak et al47 | Severe haemorrhagic CRVO | Retrospective | 11 patientsAverage 9 months (5–12 months range) | All had initial VA <20/400All had improved fundus pics (photos + FFA)Equal or better Snellen VA in 9/11 patients (82%)VA improved in 8/11 patients (73%) – average 5 lines improvement (range 3–7 lines)7/11 patients (73%) had final VA >20/2005/11 patients (45%) had final VA >20/702/11 patients had 20/40 final VA2 patients had worse VA both had iris rubeosis | NilPotentialLaceration of CRV or CRA optic nerve damage, globe perforation, retinal detachmentAverage duration of CRVO 4 months (range 1–7 months)Single surgeonFinal VA did not correlate with duration of CRVO or presence of systemic changesYounger age of onset tended to give worse prognosis: patients with equal or worse VA had average age 54 and with improved VA 64 years | ||

| Garcia‐Arumi et al51 | CRVO | Prospective case series no control group | 57% patients gained 1 or more line of vision, 43% patients improved in visual acuity by 2 or more lines | ||||

| Weizer et al50 | CRVO | Interventional case series | 5 patients4.5 months follow up | 4 patients (80%) had improved VA, 2 patients (40%) improved to 20/80 postop. In 80% disc congestion improved and intraretinal haemorrhages resolved faster than expected | 40% incidence of neovascularisation requiring PRP | ||

| Isovolaemic haemodilution | |||||||

| Glacet‐Bernard et al44 | Central or hemiretinal vein occlusion | Prospective | 142 patients10 months follow up | 41% people treated within 2 weeks had a VA of 20/40 v 23% in the late treatment group. Final retinal ischaemia was greater in the late treatment group | Early treatment gave better results | ||

| Hansen et al45 | Ischaemic and non‐ischaemic CRVO | Prospective randomised controlled trial | 19 patients (IHD + PRP) and 19 controls (PRP)1 year follow up | Patients treated with IHD and PRP had a statistically significant improvement in VA compared to PRP alone | |||

| Hansen et al49 | Non‐ischaemic CRVO | Randomised controlled trial | 14 patients and 14 controls1 year follow up | 8 of 14 study patients had improved VA compared to none of the controls | Study stopped early because of treatment benefit | ||

| Optic nerve sheath decompression | |||||||

| Dev and Buckley58 | All with optic nerve oedema | 8 patients,12.4 months follow up(3–27 months) | Mean preoperatively VA 20/160, mean postoperative VA 20/70. 6 patients improved in VA | ||||

| Laser chorioretinal venous anastamosis | |||||||

| McAllister et al62 | Non‐ischaemic CRVO | Retrospective consecutive series | 91 patients,12 months | Successful anastomosis in 49 eyes (54%)84% eyes had average ↑ VA of 4.3 lines ±3.8 lines (range 2–20 lines)16% had no improvement (6 eyes, 12%) or ↓ vision (2 eyes, 4%)No progression to ischaemia in eyes without anastomosis:17 eyes (40.5%) had ↑ VA8 (19%) had same VA17 (40.5%) had ↓ VASignificant difference between groups. Progression to ischaemia in 15 eyes (38%) | 18 (20%) had neovascular complications—intravitreal, intraretinal, and subretinal neovascular membranes significantly associated with retinal ischaemia (p<0.001)Immediate:Subretinal haemorrhageVitreous haemorrhageLate:Distal vein closureFibrovascular proliferation, NVE, progressive capillary non‐perfusion in 19 eyes (21%) | ||

| Fekrat et al64 | CRVO + BRVO | Retrospective review | 24 patients | CRVOanastomosis formed in 9/24 eyes (38%) (2/9 of these eyes had undergone grid laser Rx previously) within 2/12VA ↑6 + lines in 2/24 eyes (8%), 1–3 lines in 5/24 (21%), no change in 2 eyes (8%) (chronic CMO + focal RPE hyperpigmentation)BRVO3/6 eyes form anastmosis (50%)VA ↑1–3 lines in 2 eyes (33%), no change in 1 (16%) | Vitreous haemorrhagePreretinal fibrosisLocalised choroidal neovascularisation4 months plus before Rx | ||

| Surgical chorioretinal venous anastomosis | |||||||

| Peyman et al66 | Ischaemic CRVO | 5 patients,mean follow up13.4 months | VA ↑ in 3 eyes, unchanged in 1 eye, ↓ in 1 eye | Minor fibrous proliferationFailure to form at siteComplications of vitrectomy | |||

Interventions for CRVO

Steroids

The use of steroids is advocated by those who propose an inflammatory mechanism for the pathogenesis of CRVO. Systemic steroid treatment may be considered in patients with non‐ischaemic CRVO with an inflammatory component.10 This may be particularly justified in patients with an underlying systemic vasculitic disorder or younger patients who classically tend to have papillophlebitis. In a report of two patients pulse steroid therapy was found to increase visual acuity from 3/60 (20/800) to 6/7.5 (20/25) and from 6/24 (20/80) to 6/12 (20/40).11

Local injection of steroid into the vitreous limits the side effects of systemic steroid therapy and is shown to give both anatomical (as shown by optical coherence tomography) and functional (visual acuity) improvement in macular oedema following vein occlusion.12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 Steroids may work by stabilising the blood‐retina barrier.21 In vitro corticosteroids inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression22 and may thus prevent the neovascular sequelae of vein occlusion and reduce VEGF mediated retinal capillary permeability.18

Intravitreal steroids, particularly triamcinolone, seem effective in treating neovascularisation and macular oedema for both ischaemic and non‐ischaemic types of vein occlusion.16,23,24,25 Intravitreal steroid injection is a quick procedure that can be performed in an outpatient setting. Steroids are an option when patients with macular oedema are not eligible for or are resistant to laser photocoagulation. However, since the response appears short lived11,13,15 steroids may be not be suitable as definitive treatment. The risks of steroid administration must also be considered. Raised intraocular pressure is reported to occur in up to 25% eyes after intravitreal steroid20 and can make the eye prone to further ischaemic insult. The development of intractable glaucoma has also been reported.26 Other risks include infection, cataract, haemorrhage, and retinal detachment.

In chronic macular oedema there is a suggestion that anatomical success does not equate with functional improvement.13 Perhaps early treatment is necessary for visual improvement before longstanding macular oedema results in irreversible photoreceptor damage. Until a large case‐control or randomised controlled series is available recommendations cannot be made on dosage, timing, and case selection for the use of steroids.

Anticoagulation and thrombolysis

It is postulated that dissolving the thrombus causing CRVO at the lamina cribrosa and/or preventing its reformation (through anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy) should effectively restore retinal blood flow and visual function. Even if irreversible damage has occurred rapid restoration of normal retinal blood flow, through clot dissolution, may prevent further visual loss from the chronic complications of CRVO.

Systemic anticoagulants (such as oral aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, or intravenous thrombolysis) have not been shown to be an effective treatment for vein occlusions.27,28 In addition, their use causes unacceptable risks of intraocular, intracerebral, and gastrointestinal haemorrhage.29,30 Consequently, local routes of administration of thrombolytic agents have been investigated.

Intravitreal thrombolysis

The rationale for intravitreal administration of tissue plasminogen activator (t‐PA) is that it can diffuse across the internal limiting membrane of the retina and enter the retinal circulation through capillaries damaged by breakdown of the blood‐retina barrier following CRVO. The t‐PA would then be transported by residual venous flow towards the lamina cribrosa, the presumed site of thrombus, to cause thrombus lysis.

Lahey et al reported that eight (34.8%) of 23 patients achieved vision greater than or equal to 6/12 (20/40) at 3 months after intravitreal injection of t‐PA. This included an eye that went from 3/60 (20/400) to 6/7.5 (20/25) and another from 1/60 (3/200) to 6/6 (20/20).31 In the CVOS, only 3.2% of 155 eyes achieved this level of vision at 4 months. Glacet‐Bernard et al also found that vision improved to at least 20/30 in 36% eyes following intravitreal thrombolysis.32 Success was not universal. This may reflect the varying maturity of the clots at the time of intervention, as animal studies suggest that t‐PA is most effective in immature clots.33 Co‐existent poor retinal perfusion may limit visual improvement. Important factors that seemed to determine outcome were the type of CRVO, and the timing of intervention. However, the lack of a control group in these studies and the small patient numbers means there is insufficient material for substantive conclusions to be reached.

Complications of intravitreal thrombolysis include vitreous haemorrhage and an increase in macular oedema.31,32 It is suggested that t‐PA may have lysed smaller secondary fibrin clots at the retinal capillary level that are deposited in response to the damage caused by the vein occlusion. If this occurs without the clot at the lamina cribrosa being lysed, the retinal venous pressure remains elevated and there may be an increase in exudation which can lead to increased macular oedema. The most dramatic improvement following t‐PA was seen in non‐ischaemic CRVO.34,35

Retinal venous thrombolysis

Retinal vein cannulation allows t‐PA to be delivered under direct view into the retinal vein to cause thrombolysis. After the initial report of this procedure36 Weiss and Bynoe conducted a prospective interventional case series of 28 patients with an average duration of CRVO of 4.9 months and visual acuity of 3/60 (20/400) or worse37; 22 of the 28 patients (79%) who underwent the procedure had better visual acuity at the final follow up examination than at baseline. Ten eyes (36%) improved by at least five lines of vision at the last follow up and five eyes improved by at least eight lines. One eye recovered from 3/60 (20/400) preoperatively to 6/6 (20/20) postoperatively. Side effects were, however, significant. Vitreous haemorrhage was seen in seven patients (25%) and one patient went on to develop a retinal detachment.

Weiss and Bynoe propose that direct venous thrombolysis provides a high local concentration of t‐PA which is delivered at a high flow rate and can act to flush out the thrombus. However, the law of haemodynamics suggest that when CRVO is longstanding the t‐PA would follow the path of least resistance and be flushed out of the central retinal vein via the collateral vessels that have developed with little t‐PA remaining to act on the thrombus.38 However, if t‐PA is injected early after onset of the vein occlusion, collateral vessels will not yet have developed and the t‐PA may then reach the desired site. Further studies are needed on the optimal timing for intervention.

Ophthalmic artery thrombolysis

Recent advances in interventional neuroradiology have made it possible to selectively catheterise the ophthalmic artery and infuse a fibrinolytic agent close to the obstruction site.

Three studies have been reported using this novel technique in patients with CRVO.39,40,41 The internal carotid artery was catheterised via the femoral artery. An initial arteriogram was used to fashion the tip of the microcatheter in accordance with the geometry of the carotid arterial siphon and ophthalmic arterial ostium. Urokinase was then infused over 1 hour. Subsequently, all patients were given intravenous heparin for 48 hours, followed by subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin for 1 month (to inhibit coagulation on the thrombus and limit clot extension and recurrence) and oral aspirin for 3 months (to combat risk factors for atherosclerosis and prevent further thrombosis).

In a retrospective study of 26 patients (all with VA less than 6/18 (20/60)) six patients had improved vision after 48 hours, which was maintained long term in five patients.39 In a subgroup analysis, four of the six patients with visual improvement had pretreatment Funduscopic appearances suggestive of combined central retinal artery and vein occlusion. This pattern was seen in nine of 26 patients in the series. Thus, overall, four out of the nine (44%) patients with this pattern improved.

In a prospective series of five patients, three who had the features of combined central retinal artery and vein occlusion achieved full visual recovery after this intervention.40 These patients had visual loss of less than 30 days' duration with visual acuity less than 6/30 (20/100). These patients had no capillary closure, and four of them had no macular oedema. It seems, therefore, that impairment of retinal arterial perfusion was responsible for their visual loss and minimally invasive local intra‐arterial thrombolysis had a rapid beneficial effect.

Since patients with combined central retinal artery and vein occlusion were found to respond well to thrombolysis,39,40 a separate prospective study was undertaken on this group of patients.41 Eleven consecutive patients with visual loss of less than 72 hours were treated during a 6 year period. Vision improved at some point after treatment in seven of 11 patients, including six in who substantial improvement after 24–48 hours. Funduscopy showed the retinal pathology to regress over 2–4 weeks.

Complications encountered include vitreous haemorrhage which may lead to blindness.41 The haemorrhage may have resulted from rupture of ischaemic retinal vessels caused by severely impaired retinal arterial perfusion as well as a combined sudden increase in retinal venous hydrostatic pressure caused by venous thrombosis as a result of the release of arterial thrombosis by fibrinolysis. Local administration of thrombolytics avoids systemic complications or change in clotting status. There were no cases of post‐procedure neurological deficit.

There is the possible requirement for long term anticoagulation following thrombolysis. One patient had a repeat CRVO just over 1 month after thrombolysis when heparin was stopped. Similarly, stopping aspirin led to a further decrease in vision from 6/15 (20/50) to 6/60 (20/200) as a result of cystoid macular oedema.40

The local administration of thrombolytic agents is a feasible treatment for RVO but may only be beneficial in certain types of RVOs. In addition, it seems appropriate to administer treatment before the thrombus becomes organised. Promising results are seen in patients with combined central retinal artery and vein occlusion. Unfortunately, the studies lack a control group and spontaneous improvement of this subgroup has been reported.42

Isovolaemic haemodilution

Whatever the primary cause of RVO , the obstruction causes a local increase in blood viscosity. In isovolaemic haemodilution, venesection is performed at the same time as infusion of a plasma substitute (for example, hydroxyethyl starch, dextran) so that a constant blood volume is maintained. By reducing the haematocrit level, haemodilution causes a reduction in blood viscosity and thus improves retinal blood flow and oxygen supply. Thus, it relieves retinal hypoperfusion during a critical time of occlusion and may prevent capillary closure and further retinal ischaemia.

Haemodilution therapy has been shown to be an effective intervention for CRVO in a number of randomised studies. Beneficial effects have been seen with respect to visual acuity, retinal circulation times, and haemorheological parameters.43,44,45,46

Hansen et al carried out a prospective randomised trial evaluating the efficacy of combined isovolaemic haemodilution and panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) in patients with ischaemic and non‐ischaemic CRVO. Patients treated with haemodilution and PRP showed a statistically significant improvement in vision compared to patients treated with PRP alone up to 1 year later. In both groups the final visual acuity was worse for ischaemic CRVO. However, the most marked improvement in visual acuity was seen in patients with ischaemic CRVO but this did not reach statistical significance as the numbers of patients were small.45

Hansen et al demonstrated a significant treatment effect with the use of isovolaemic haemodilution alone in non‐ischaemic CRVO. Eight of 14 patients with non‐ischaemic CRVO who were given isovolaemic haemodilution alone had improved in visual acuity compared to none of the 11 controls (p<0.01).46

The importance of early intervention was shown by Glacet‐Bernard et al, who analysed 142 patients with central or hemiretinal vein occlusion. Final visual acuity was significantly better if treatment was instituted within the first 2 weeks of vein occlusion; 41% had a final visual acuity of 20/40 or better in this early treatment group versus 23% in the late treatment group (p<0.01).44

Ischaemic change may underlie the need for early intervention. In Glacet‐Bernard's study retinal ischaemia was not significantly greater in the late treatment group at inclusion but at the end of follow up ischaemic change was significantly greater in the late treatment group. Isovolaemic haemodilution thus seems to prevent retinal ischaemia and risk of conversion of non‐ischaemic RVO to ischaemic RVO.

Isovolaemic haemodilution is a systemic treatment. Patients having this treatment would need to be carefully selected. It may not be suitable for patients with CCF, renal or respiratory insufficiency and anaemia. Isovolaemic haemodilution alone has not been shown to prevent neovascular glaucoma or to arrest ischaemia and therefore most studies have used adjunctive laser therapy.44,45

Radial optic neurotomy

It is thought that radial optic neurotomy releases pressure in the scleral outlet compartment (the space containing the scleral canal, cribriform plate, optic nerve, central retinal artery and vein). This increases the central retinal vein lumen which in turn increases venous flow and helps clear the thrombus.

Examination of cadaveric eyes showed that the scleral outlet could be decompressed via an internal vitreoretinal approach.47 A standard three port vitrectomy is done and the intraocular pressure raised to minimise any potential bleeding. A radial optic neurotomy is done using a microvitreoretinal (MVR) blade on the nasal side of the disc to avoid injury to the papillomacular bundle. The cut is radial (non‐radial cuts would transect the nerve fibre layer neurons as they enter the optic nerve) and approaches the centre of the cribriform plate.

The Radial Optic Neurotomy Study is a retrospective non‐randomised pilot study of 11 consecutive patients with severe haemorrhagic CRVO.47 In the selected patient group, with visual acuity equal to or less than 3/60 (20/400), prognosis is normally poor without intervention.3 Surgical relaxation of the scleral outlet was associated with a dramatic and rapid clearing of intraretinal haemorrhages and improved retinal blood flow in all patients. Visual acuity improved in eight of the 11 patients (73%) with an average of five Snellen lines improvement. The final visual acuity did not correlate with duration of CRVO or the presence of systemic disease. A younger age of onset tended to show a poorer visual prognosis.

These impressive results have been criticised by some authors, who suggest that the use of Snellen acuity (rather than the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) acuity used in the CVOS) may have underestimated the actual presenting visual acuity, and that these patients may have had favourable natural outcomes without intervention.48 Retinal capillary non‐perfusion was used as the only criterion to make the distinction between ischaemic and non‐ischaemic CRVO. Unfortunately, this criterion on its own has poor reliability in making such differentiation in the early stages of CRVO.49 However, the distinction is vital in determining prognosis. Further, no visual field evaluations were undertaken in this study and as such no comment could be made on the occurrence of optic nerve damage.

More modest results are seen in a small interventional case series of five patients,50 where a 40% incidence of rubeosis iridis was reported post‐procedure. Similarly, modest results are reported by Garcia‐Arumi et al, where 43% patients improved in visual acuity by two or more lines in an uncontrolled study.51

Potential complications include laceration of the central retinal artery or nerve, optic nerve damage, globe perforation, and retinal detachment. Visual field defects may occur because of optic nerve head ischaemia after cutting the circle of Zinn‐Haller or nerve fibre transection.52 Currently, the anatomical success of the technique outweighs functional success and prospective randomised studies are needed.

The rationale for this procedure is difficult to understand. The presence of a hypothetical bottleneck at the optic nerve head is not logical given that the difference in diameter between retrolaminar and prelaminar optic nerves could be explained by the presence of a myelin sheath. The theory would also not be able to explain the development of a hemiretinal vein occlusion.53 The central retinal vein lies temporal to the artery in the optic nerve, enclosed by a common fibrous capsule. Thus, the nasal cut in radial optic neurotomy cannot decompress the vein.54

Optic nerve sheath decompression

The rationale for optic nerve sheath decompression is that optic nerve oedema results in some degree of mechanical venous compression. This hypothesis is based on previous studies on posterior scleral ring section55,56 and the demonstration of decreased retinal vein calibre after optic nerve sheath decompression in patients with pseudotumour cerebri.57

Optic nerve sheath decompression was performed in eight patients with progressive CRVO and optic nerve oedema. The mean follow up period was 12.4 months.58 Overall, six patients improved in visual acuity. Mean preoperative vision was 6/48 (20/160) and mean postoperative vision was 6/21 (20/70). The probability of improvement in visual acuity is reported to be 75%. Non‐ischaemic eyes operated on within 3 months of CRVO onset, age under 65 years, and initial visual acuity greater than 6/60 (20/200) appear to have had better outcomes.

These data seem to argue for a potential role of this procedure in selected cases. However, without a randomised controlled trial and a larger number of patients it is difficult to assess the efficacy of the procedure for this indication.

Lamina puncture

This is transvitreal optic disc surgery to create a perivascular opening in the lamina cribrosa. This aims to release the postulated constriction of the central retinal vein by the surrounding connective tissue at the level of the lamina cribrosa. The resultant increase in luminal diameter of the central retinal vein may allow the passage of the thrombus or relieve the pressure predisposing to thrombus formation. Alternatively, it may allow sufficient blood flow at the level of the lamina cribrosa to permit increased retinal perfusion, even if the thrombus is not dislodged or mechanically expressed. Thus far the technical feasibility has been established only on human cadaver and enucleated pig eyes.59 Until in vivo trials are performed it is not possible to determine if this will lead to success.

Chorioretinal venous anastomosis

First described almost 50 years ago by Verhoeff,60 chorioretinal anastomosis allows blood to bypass the occluded vein into the choroidal circulation. It is thought that vision is improved by a reduction in macular oedema and in progression to an ischaemic status.

This technique has been applied to both BRVO and CRVO and may be done either by laser or surgery. Patient numbers for BRVO are too low for meaningful evaluation.

Chorioretinal venous anastomosis by laser

The effect of laser induced chorioretinal anastomosis depends on the type of RVO and the establishment of a successful anastomosis. The best results of this procedure have been found in non‐ischaemic CRVO where approximately one third to one half of patients develop a functionally effective chorioretinal anastomosis. Chorioretinal venous anastomosis in ischaemic eyes is very difficult to achieve, perhaps because of the presence of endothelial cell damage.61 Although a successful anastomosis prevents further progression towards ischaemia,62 the visual results of chorioretinal anastomosis are poor.62,63,64,65

Complications of this procedure include vitreous haemorrhage (42%), choroidal neovascularisation (21%), and pre‐retinal fibrosis (12%).62,64 Complications are magnified in ischaemic CRVO.62

In order to reduce the risk of neovascular complications, chorioretinal venous anastomosis should perhaps be limited to non‐ischaemic CRVO and patients treated by this technique should be closely followed up. Optimal timing of intervention is unclear but one study suggests it should be less than 4 months, since the average time for the anastomosis to become functional is 6.7 weeks and because an average of 2.1 attempts are needed to establish an anastomosis.62

Much work is needed in this field. The ophthalmoscopic and angiographic criteria required to determine the presence of chorioretinal anastomosis have not yet been well described. Further evaluation of the laser power required to produce an anastomosis is necessary. Reasons why some eyes respond to laser by forming anastomosis while others develop a fibrovascular response are unclear. Factors that determine whether or not an anastomosis forms include patient's age, presence of optic nerve head collaterals, the presence of an underlying choroidal vein near the treatment site, and degree of intravascular pressure elevation in the obstructed vein.

Chorioretinal venous anastomosis by surgery

Given the unpredictable yield of laser induced chorioretinal anastomosis, surgical methods are being evaluated. In a pilot study pars plana vitrectomy was followed by slit‐like incisions through Bruch's membrane adjacent to a major branch of a retinal vein in each quadrant.66 Small pieces of 5/0 madrilene suture were placed over the vein and inserted into these incision sites to maintain its patency and promote the formation of collaterals. Endolaser treatment was then performed around the incision site followed by panretinal laser photocoagulation.

Of 16 attempted chorioretinal venous anastomosis sites, 10 were functioning. In all cases there was proliferation of avascular fibrous tissue. Final visual acuity was better in three eyes. Larger trials are awaited.

Interventions for BRVO

Steroids

Similar to their use in CRVO, the use of intravitreal triamcinolone has recently been advocated in BRVO patients and, in a controlled study, was shown to significantly improve visual acuity in patients with chronic macular oedema.26 Further work is awaited. The risks of this treatment are comparable to those for CRVO.

Isovolaemic haemodilution

Chen et al demonstrated positive results for isovolaemic haemodilution given up to 3 months after BRVO in a randomised controlled study; 18 patients were treated for 6 weeks and compared to 16 control patients. After 1 year of follow up the visual acuity in the treated group improved compared to the controls (p = 0.03). Final visual acuities were 6/12 and 6/24 for treated and untreated patients, respectively. At the 3 month follow up argon laser treatment was given for macular oedema and vision less than 6/12, neovascularisation or capillary non‐operfusion greater than 5 disc diameters. There was no significant difference between cases and controls requiring laser treatment. It therefore appears that isovolaemic haemodilution may be of benefit in both CRVO and BRVO.43

Vitrectomy

The vitreous is postulated to have a role in the pathogenesis of neovascularisation and macular oedema, which may complicate BRVO and its removal may help in the management of these sight threatening complications.

An intact vitreoretinal surface provides a scaffold for neovascularisation.67,68 The vitreous allows angiogenic factors from the ischaemic retina to diffuse into it and traction through the vitreous fibres on the Muller cells of the retina predisposes to cystoid macular oedema.69 Animal studies on vitrectomised and non‐vitrectomised eyes show that inducing a BRVO in non‐vitrectomised eyes results in retinal hypoxia, whereas BRVO induced in vitrectomised eyes produced no change in retinal oxygen tension.70

It is postulated that vitrectomy allows access of oxygenated aqueous to the inner retina, thereby improving macular oedema, reducing ischaemia, and improving vision. Pars plana vitrectomy has been shown to reduce macular oedema and restore the normal foveal contour but there was no significant change in best corrected visual acuity.

Visual improvement occurs after vitrectomy for vitreous haemorrhage or retinal detachment complicating BRVO.71,72 This is an established treatment for these complications. No studies are available on vitrectomy being performed before the development of these complications.

Arteriovenous crossing sheathotomy

Venous compression in BRVO may be relieved by dividing the common adventitial sheath that surrounds retinal arterioles and venules at arteriovenous (A‐V) crossing points.

An initial case report in a 54 year old woman with a 3 week history of BRVO showed visual improvement from 6/60 (20/200) to 6/7.5 (20/25) after 8 months' follow up.73 However, the re‐perfusion status was not indicated. In a small uncontrolled prospective series of 15 eyes, Opremcak and Bruce reported results after A‐V sheathotomy with BRVO and 6/21 (20/70) or worse Snellen visual acuity.74 In all patients, intraoperative sheath decompression was achieved, resulting in clinical improvements in retinal haemorrhages and retinal perfusion. Postoperative visual acuity improved in 10 of 15 patients (67%) with an average of four lines of vision gained. Nevertheless, vision did not improve in three patients despite surgical success and resolution of fundus changes. This was attributed by the authors, to a postoperative IOP rise. Two patients developed vascular bleeding as a result of an anatomical variation in vessel configuration at the A‐V crossing point of the BRVO. The authors did not report visual recovery to correlate with initial visual acuity, duration of the BRVO, severity of intraretinal haemorrhage, oedema or ischaemia, or with final visual acuity.

In a controlled prospective study 43 patients with BRVO were treated with A‐V decompression while 25 patients who refused surgery acted as controls.75 The mean VA improved from 0.35 to 0.16 on the logMAR scale; 26 patients (60%) gained at least two lines of vision and 12 patients (28%) gained at least four lines of vision. After 6 weeks' follow up, macular oedema and retinal haemorrhages had resolved. Patients with the most improvement also showed angiographic improvements in venous perfusion, whereas four patients with completely occluded vessels showed the worst functional results. Despite visual improvement, capillary reperfusion was only observed in four eyes. Overall, the functional outcome were significantly better in patients with A‐V decompression than controls and outcomes were more favourable in patients under 65 years of age.75,76 This may be explained by the advanced sclerotic changes of the blood vessels in older patients.

Retrospective studies have similarly shown benefits from A‐V sheathotomy.77,78 Although the case series are small, visual improvements of 80% have been demonstrated in patients with preoperative vision of 6/60 (20/200). These studies have follow ups ranging from 5–7 years. Cahill et al report a complete resolution of macular oedema and a significant increase in visual acuity in one third of patients after A‐V sheathotomy.79 However, in the majority of cases a reduction of oedema was not associated with improved visual acuity.

The optimum timing of intervention is unclear. Some investigators have reported successful surgical intervention after as long as 6 months.74 In other studies if the preoperatively duration of BRVO was 3 months, the results were worse than those cases where a shorter interval occurred between BRVO and surgery.

Reported complications are few but include cataract, nerve fibre layer defects, haemorrhage, retinal tear, postoperative gliosis, and retinal detachment.

Although preliminary results are encouraging, further questions remain. What is the time window in which decompression would give optimal results? Will A‐V sheathotomy be more effective if performed before the thrombus becomes organised? The success of A‐V sheathotomy may be partly attributed to the vitrectomy performed at the same time which resulted in preventing neovascularisation and persistent macular oedema.80 Further investigations are required to better define what degree of functional deterioration caused by BRVO mandates surgical intervention. It may be that a combination approach is needed—such as A‐V sheathotomy and injection of thrombolytic into the occluded vein, which resulted in thrombus release in 28% cases and significant correlation with early surgery and better final visual acuity.81

Conclusion

Retinal vein occlusions are the second most common sight threatening vascular disorder. Despite this, our therapeutic armamentarium for functional improvement has been very limited. We are now moving into a new era where many novel interventional treatments have been described for RVOs.

There are three main deficiencies in the evidence we currently have for interventional treatments in RVO. The main observation is the lack of large well designed prospective randomised controlled trials. Pilot studies on interventional treatments for vein occlusion seem promising but all are non‐randomised and uncontrolled studies in small numbers of patients. Randomised controlled trials remain the gold standard of research methodology and provide the best indication of treatment effect. Until these are available many ophthalmologists will be reluctant to change their practice.

Secondly, there is lack of long term follow up in many studies. While some interventions (for example, intravitreal steroids) seem to have a temporary effect, we do not know the long term outcomes of other measures. The third issue to address is optimal timing of intervention and patient selection. Ideally, early intervention would be best before thrombus organisation or further ischaemic damage occurs but the effective treatment window remains obscure. Most interventions appear to be more successful in non‐ischaemic vein occlusions but further clarification is necessary.

At present the evidence to date does not support any therapeutic benefit from radial optic neurotomy, optic nerve sheath decompression or A‐V crossing sheathotomy in eyes with vein occlusion. Furthermore, the potential complications outweigh any benefits. The use of isovolaemic haemodilution requires careful patient selection and should be avoided in patients with concurrent cardiovascular, renal, or pulmonary disease. Unfortunately, as a significant number of patients with vein occlusion have concurrent cardiovascular morbidity, and the benefits are limited, we would not recommend haemodilution.

With the available evidence we have we suggest that the use of intravitreal steroids may be a beneficial early intervention in carefully selected patients with CRVO or BRVO. Intravitreal steroids have been evaluated in non‐randomised comparative studies and have been shown to be significantly better than no treatment, and although the steroid effect is not permanent it may prevent early photoreceptor damage from macular oedema and improve long term prognosis. Anti‐VEGF agents, which are gaining popularity in treatment of choroidal neovascularisation, may have a role in future.

Vitrectomy with intravenous thrombolysis with t‐PA seems to offer the most promising option for CRVO. This procedure seems to give the best outcome with fewer side effects. It also seems the most physiological of all the presently suggested options. Similarly, although not tried yet, vitrectomy, A‐V sheathotomy combined with intravenous t‐PA may offer benefits in BRVO.

Despite uncertainty and open questions, surgical interventions are likely to be a therapeutic option for RVO in the future. Vein occlusions occur at a sufficiently high frequency for future prospective randomised controlled studies to be conducted so that we can truly evaluate the role of each therapeutic modality both individually and in combination.

Abbreviations

A‐V - arteriovenous

BRVO - branch retinal vein occlusion

BVOS - Branch Vein Occlusion Study

CRVO - central retinal vein occlusion

CVOS - Central Vein Occlusion Study

ETDRS - Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study

MVR - microvitreoretinal

PRP - panretinal photocoagulation

RVO - retinal vein occlusion

t‐PA - tissue plasminogen activator

VEGF - vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Proprietary interest: none.

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Branch Vein Occlusion Study Group Argon laser photocoagulation for macular edema in branch vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 198498271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayreh S S, Zimmerman M B, Podhajsky P. Incidence of various types of retinal vein occlusion and their recurrence and demographic characteristics. Am J Ophthalmol 1994117429–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Central Vein Occlusion Study Group Natural history and clinical management of central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 1997115486–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Central Vein Occlusion Study Group Baseline and early natural history report. Arch Ophthalmol 19931111087–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell P, Smith W, Chang A. Prevalence and associations of retinal vein occlusion in Australia. The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol 19961141243–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinlan P M, Elman M J, Bhatt A K.et al The natural course of central retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 1990110118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zegarra H, Gutman F A, Conforto J. The natural course of central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology 1979861931–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Central Vein Occlusion Study Group M Report Evaluation of grid pattern photocoagulation for macular oedema in central vein occlusion. Ophthalmology 19951021425–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branch Vein Occlusion Study Group Argon laser scatter photocoagulation for prevention of neovascularization and vitreous hemorrhage in branch vein occlusion. A randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol 198610434–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayreh S S. Central retinal vein occlusion: differential diagnosis and management. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 197783(3 Pt 1)OP379–OP391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaikh S, Blumenkranz M S. Transient improvement in visual acuity and macular edema in central retinal vein occlusion accompanied by inflammatory features after pulse steroid and anti‐inflammatory therapy. Retina 200121176–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Degenring R F, Kamppeter B, Kreissig I.et al Morphological and functional changes after intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for retinal vein occlusion. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 200381548–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg P B, Martidis A, Rogers A H.et al Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for macular oedema due to central retinal vein occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol 200286247–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ip M, Kahana A, Altaweel M. Treatment of central retinal vein occlusion with triamcinolone acetonide: an optical coherence tomography study. Sem Ophthalmol 20031867–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ip M S, Kumar K S. Intravitreous triamcinolone acetonide as treatment for macular edema from central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 20021201217–1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonas J B, Kreissig I, Degenring R F. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide as treatment of macular edema in central retinal vein occlusion. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2002240782–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park C H, Jaffe G J, Fekrat S. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide in eyes with cystoid macular edema associated with central retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 2003136419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ip M S, Gottlieb J L, Kahana A.et al Intravitreal triamcinolone for the treatment of macular oedema associated with central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 20041221131–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bashshur Z F, Ma'luf R N, Allam S.et al Intravitreal triamcinolone for the management of macular oedema due to nonischaemic central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 20041221137–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antcliff R J, Spalton D J, Stanford M R.et al Intravitreal triamcinolone for uveitic cystoid macular oedema: an optical coherence tomography study. Ophthalmology 2001108765–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson C A, Berkowitz B A, Sato Y.et al Treatment with intravitreal steroid reduces blood‐retina barrier breakdown due to retinal photocoagulation. Arch Ophthalmol 19921101155–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nauck M, Karakiulakis G, Perrochoud A P.et al Corticosteroids inhibit the expression at the vascular endothelial growth factor gene in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol 1998341309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonas J B, Hayler J K, Sofker A.et al Regression of neovascular iris vessels by intravitreal injection of crystalline cortisone. J Glaucoma 200110284–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen S D, Lochhead J, Patel C K.et al Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for ischaemic macular oedema caused by branch retinal vein occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol 200488154–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jonas J B, Akkoyun I, Kamppeter B.et al Branch retinal vein occlusion treated by intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide. Eye. April 2004; Advance e‐pub [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Kaushik S, Gupta V, Gupta A.et al Intractable glaucoma following intravitreal triamcinolone in central retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 2004137758–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duff I F, Falls H F, Linman J W. Anticoagulant therapy in occlusive vascular disease of the retina. Am Arch Ophthalmol 195146601–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vannas S, Ritta C. On anticoagulant treatment of occlusion of the central vein of the retina. Acta Ophthalmol 196846730–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohner E M, Pettit J E, Hamilton A M.et al Streptokinase in central retinal vein occlusion: a controlled clinical trial. BMJ 19761550–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elman M J. Thrombolytic therapy for central retinal vein occlusion: results of a pilot study. Trans Am Ophthal Soc 1996XCIV471–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lahey J M, Fong D S, Kearney J. Intravitreal tissue plasminogen activator for acute central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 199930427–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glacet‐Bernard A, Kuhn D, Vine A K.et al Treatment of recent onset central retinal vein occlusion with intravitreal tissue plasminogen activator: a pilot study. Br J Ophthalmol 200084609–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loren L J, Frade G, Torrado M C.et al Thrombus age and tissue plasminogen activator mediated thrombolysis in rats. Thromb Res 19895667–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elman M J, Raden R Z, Carrigan A. Intravitreal injection of tissue plasminogen activator for central retinal vein occlusion. Trans Am Ophthal Soc 200199219–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghazi N G, Noureddine B, Haddad R S.et al Intravitreal tissue plasminogen activator in the management of central retinal vein occlusion. Retina 200323780–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss J N. Treatment of central retinal vein occlusion by injection of tissue plasminogen activator into a retinal vein. Am J Ophthalmol 1998126142–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss J N, Bynoe L A. Injection of tissue plasminogen activator into a branch retinal vein in eyes with central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology 20011082249–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayreh S S. t‐PA in CRVO. Ophthalmology 20021091758–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paques M, Vallee J N, Herbreteau D.et al Superselective ophthalmic artery fibrinolytic therapy for the treatment of central retinal vein occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol 2000841387–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vallee J N, Massin P, Aymard A.et al Superselective ophthalmic arterial fibrinolysis with urokinase for recent severe central retinal venous occlusion: initial experience. Radiology 200021647–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vallee J N, Pacques M, Aymard A.et al Combined central retinal arterial and venous obstruction: emergency ophthalmic arterial fibrinolysis. Radiology 2002223351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jorizzo P A, Klein M L, Shults W T.et al Visual recovery in combined central artery and central vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 1987104358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen H C, Wiek J, Gupta A.et al Effect of isovolaemic haemodilution on visual outcome in branch retinal vein occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol 199882162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glacet‐Bernard A, Zourdani A, Milhoub M.et al Effect of isovoemic hemodilution in central retinal vein occlusion. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2001239909–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hansen L L, Danisevskis P, Arntz H‐R.et al A randomised prospective study on treatment of central retinal vein occlusion by isovolaemic haemodilution and photocoagulation. Br J Ophthalmol 198569108–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansen L L, Wiek J, Wiederholt M.et al A randomised prospective study of treatment of non‐ischaemic central retinal vein occlusion by isovolaemic haemodilution. Br J Ophthalmol 198973895–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Opremcak E M, Bruce R A, Lomeo M D.et al Radial optic neurotomy for central retinal vein occlusion: a retrospective pilot study of 11 consecutive cases. Retina 200121408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bynoe L A, Opremcak E M, Bruce R A.et al Radial optic neurotomy for central retinal vein obstruction. Retina 200222379–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayreh S S, Opremcak E M. Radial optic neurotomy for central retinal vein occlusion. Retina 200222374–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weizer J S, Stinnett S S, Fekrat S. Radial optic neurotomy as treatment for central retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 2003136814–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garciia‐Arumii J, Boixadera A, Martinez‐Castillo V.et al Chorioretinal anastomosis after radial optic neurotomy for central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 20031211385–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williamson T H, Poon W, Whitefield N.et al A pilot study of pars plana vitrectomy, intraocular gas, and radial neurotomy in ischaemic central retinal vein occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol 2003871126–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guajardo L L, de la Huerga A M, Sandomingo A F.et al Radial optic neurotomy as a treatment of central vein occlusion: neurotomy in central vein occlusion. Retina 200323890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayreh S S. Radial optic neurotomy for nonischemic central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 20041221572–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vasco‐Pasada J. Modification of the circulation in the posterior pole of the eye. Am J Ophthalmol 1972148–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arcinegas A. Treatment of the occlusion of the retinal vein by section of the posterior ring. Ann Ophthalmol 1984161081–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee S Y, Shin O H, Spoor T O.et al Bilateral retinal venous calibre decrease following unilateral optic nerve sheath decompression. Ophthalmic Surg 19952625–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dev S, Buckley E G. Optic nerve sheath decompression for progressive central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 199930181–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lit E S, Tsilimbaris M, Gotzaridis E.et al Lamina puncture: pars plana optic disc surgery for central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 2002120495–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Verhoeff F H. Successful diathermy treatment in a case of recurring retinal haemorrhages and retinitis proliferans. Arch Ophthalmol 194840239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kwok A K H, Lee V Y W, Hon C. Laser induced chorioretinal venous anastomosis in ischaemic central retinal vein occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol 2003871043–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McAllister I L, Douglas J P, Constable I J.et al Laser‐induced chorioretinal venous anastomosis for nonischaemic central retinal vein occlusion: evaluation of the complications and their risk factors. Am J Ophthalmol 1998126219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McAllister I L, Constable I J. Laser‐induced chorioretinal venous anastomosis for treatment of nonischaemic central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 1995113456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fekrat S, Goldberg M F, Finkelstein D. Laser‐induced chorioretinal venous anastomosis for nonischaemic central or branch retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 199811643–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parodi M B. Laser‐induced chorioretinal anastomosis and central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 1999117140–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peyman G A, Kishore K, Conway M D. Surgical chorioretinal venous anastomosis for ischaemic central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 199930605–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Avunduk A M, Cetinkaya K, Kapicioglu Z.et al The effect of posterior vitreous detachment on the prognosis of branch retinal vein occlusion. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 199775441–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takahashi M K, Hikichi T, Akiba J.et al Role of the vitreous and macular oedema in branch retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 199728294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sebag J, Balazs E A. Pathogenesis of cystoid macular oedema: an anatomic consideration of vitreoretinal adhesions. Surv Ophthalmol 198428(suppl)493–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stefansson E, Novack R L, Hatchell D L. Vitrectomy prevents retinal hypoxia in branch retinal vein occlusion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 199031284–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yeshaya A, Treister G. Pars plana vitrectomy for vitreous haemorrhage and retinal vein occlusion. Ann Ophthalmol 198315615–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Amirikia A, Scott I U, Murray T G.et al Outcomes for vitreoretinal surgery for complications of branch retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology 2001108372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Osterloh M D, Charles S. Surgical decompression of branch retinal vein occlusions. Arch Ophthalmol 19881061469–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Opremcak E M, Bruce R A. Surgical decompression of branch retinal vein occlusion via arteriovenous crossing sheathotomy: a prospective review of 15 cases. Retina 1999191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mester U, Dillinger P. Vitrectomy with arteriovenous decompression and internal limiting membrane dissection in branch retinal vein occlusion. Retina 200222740–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Charbonnel J, Glacet‐Bernard A, Korobelnik J.et al Management of branch retinal vein occlusion with vitrectomy and arteriovenous adventitial sheathotomy, the possible role of surgical posterior vitreous detachment. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2004242223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shah G K, Sharma S, Fineman M S. Arteriovenous adventitial sheathotomy for the treatment of macular oedema associated with branch retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 2000129104–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shah G K. Adventitial sheathotomy for treatment of macular oedema associated with branch retinal vein occlusion. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 200011171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cahill M T, Kaiser P K, Sears J E.et al The effect of arteriovenous sheathotomy on cystoid macular oedema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol 2003871329–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Le Rouic J F, Bejjani R A, Rumen F.et al Adventitial sheathotomy for decompression of recent onset branch retinal vein occlusion. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2001239747–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Garcia‐Arumi J, Martinez‐Castillo V, Boixadera A.et al Management of macular oedema in branch retinal vein occlusion with sheathotomy and recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. Retina 200424530–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]