Abstract

Aim

To prove that topical antifungal and antibiotic prophylaxis distributed by grass roots village health workers (VHWs) in Burma is an effective public health intervention for the prevention of post‐traumatic microbial keratitis in a population where the majority of ulcers are fungal.

Methods

Three villages in Bago District with a combined population of 16 987 were selected for the study. This defined population was followed prospectively for 12 months by 15 VHWs who were trained to identify post‐traumatic corneal abrasions with fluorescein dye and a blue torch and to administer 1% chloramphenicol and 1% clotrimazole ointment three times a day for 3 days to the eyes of individuals who fulfilled the eligibility criteria.

Results

During the 12 month period 273 individuals reported to VHWs with an ocular injury and 126 were found to have a corneal abrasion. All 126 were treated with 1% chloramphenicol and 1% clotrimazole ointment three times a day for 3 days, and all healed without sequelae.

Conclusions

Both fungal and bacterial ulcers that occur following traumatic corneal abrasions can be effectively prevented in a village setting by using relatively simple measures that local volunteer public health workers can easily be taught to employ.

Keywords: corneal blindness, corneal ulceration, ulcer prevention, fungal keratitis, Burma

Corneal ulceration and subsequent corneal scarring are at present a leading cause of ocular morbidity and unilateral blindness in developing countries.1 In response to the findings of the Bhaktapur Eye Study in Nepal,2 prevention studies were initiated in three countries in South East Asia (Bhutan, Burma and India) to validate the hypothesis that corneal ulcers which occur after traumatic abrasions can be prevented in the setting of diverse health care systems and in populations with different prevalences of bacterial and fungal pathogens causing ulceration. The recently completed 18 month study in Bhutan3 validated the findings of the Nepal study by demonstrating that bacterial ulcers that occur after traumatic corneal abrasion can be effectively eliminated by a grass roots public health approach, even under the conditions that prevail in isolated rural villages. Corneal ulcer prevention in Bhutan, where 98% of the ulcers are caused by bacterial pathogens,3 was accomplished by a simple public health strategy that local volunteer village health workers were taught to employ within the existing healthcare structure.

In Burma, a country of 42 million ethnically diverse people in South East Asia, corneal ulceration is a significant cause of unilateral blindness superseded only by cataract and trachoma.4,5 Based on hospital data projected to a defined population, the World Health Organization estimates that there are 710 corneal ulcers per 100 000 population every year.6 This figure is comparable to the incidence in Nepal2 of 799 per 100 000. Prevalence studies based on data from the microbiology laboratory at the national hospital in Yangon indicate that one third of all corneal ulcers are caused by bacteria, a third are fungal, and a third are mixed bacterial and fungal infections.6 Fungal pathogens have been reported as a major cause of microbial keratitis in several countries in Africa7 and Asia8 as well, inevitably posing extremely difficult management problems. However, the situation in Burma is exceptional. Two thirds of all culture positive corneal ulcers grow fungal organisms, and coupled with the high incidence of corneal infection in the country, the blinding sequelae for the population are disastrous. It is widely believed that fungal ulcers occur after a traumatic event, usually a corneal abrasion caused by organic material.9 Therefore, it seems feasible that applying a topical antifungal ointment prophylactically to the injured eye might prevent fungal keratitis from occurring. This study proposes to test this hypothesis in a population where the ulcer incidence is high and the main risk factor for fungal keratitis is corneal trauma. Because the incidence of bacterial keratitis and mixed infections is also high, all corneal abrasions were also treated prophylactically with antibiotic ointment. In addition, we propose to test the effectiveness of a highly organised and stratified village healthcare system, such as the one that exists in Burma, in preventing corneal ulceration.

Methods

Three villages in Bago District (Payar Kalay, Wan‐be‐inn, and Pyin Bong Gyi) with a combined population of 16 987 were selected for the study. All three villages were followed for 12 months by village health workers (VHWs), who are government employees of the department of health and provide primary health care to the community. The minimum qualifications of the VHWs included a high school education and previous experience in community based work. The organisation of the district health structure consists of five rural health centres with numerous subcentres covering a total population of 30 000. To monitor a defined population of 16 987, 15 VHWs, who were already serving at the rural health centres and subcentres, were selected. Under the direction of a field supervisor from the rural health centre, a detailed map was prepared for each village noting the location of all the households and the demographic details of the residents.

On average, each VHW was responsible for 750–1000 individuals in the community. VHWs were instructed in basic eye care and taught to recognise conditions that would include or exclude an injured individual from the study. At the district referral hospital in Bago, VHWs were instructed by an ophthalmologist in the use of fluorescein strips and a blue torch and taught to identify a corneal abrasion. They were also taught how to record visual acuity using an “E” chart. Each worker was provided with a supply of sterile individually packed fluorescein strips, a pictorial study manual, a blue torch, and an “E” chart. They were also supplied with 1% chloramphenicol applicaps (Parke‐Davis) and 1% clotrimazole ointment (prepared for the study by the coordinating centre at Aravind Eye Hospital, Madurai, India). A manual of operations, record forms, and other material resources were supplied by the coordinating centre. Data were analysed using SPSS software (Statistical Package for Social Sciences).

In the villages, each VHW allotted a room in their house to store study supplies and medications, and to examine the patients. Before starting the project, a publicity campaign was launched to create community awareness. Educational materials in Burmese were displayed at rural health centres and in public places describing corneal ulcer prevention in words and photographs. Surveys were conducted periodically to test for public awareness of the study. Before starting the recruitment of the patients, a pilot study was carried out in the three villages for 1 month. After completion of the pilot study, field workers had additional refresher training and then the study was started.

Patients

Inclusion criteria:

Resident of study area

Corneal abrasion after ocular injury, confirmed by clinical examination with fluorescein stain and a blue torch

Reported within 48 hours of injury

Subject aged >5 years of age.

Exclusion criteria:

Presence of clinically evident corneal infection

Penetrating corneal injury or stromal laceration

Bilateral ocular trauma

Pre‐existing blindness (<6/60) in the non‐traumatised eye

Initiation of topical or systemic antibiotic therapy before examination by study personnel

Incomplete lid closure

Diabetes

Injuries to other vital organs/multisystem injuries requiring hospitalisation

Trichiasis

Dacryocystitis

Not willing to participate.

Treatment

Subjects meeting the eligibility criteria were started on treatment with 1% chloramphenicol applicaps and 1% clotrimazole ointment. Clotrimazole was chosen because it is a broad spectrum antifungal agent that is effective against both yeasts and filamentous fungi and can be compounded as an ointment. Verbal informed consent was obtained from the eligible subjects by the VHWs. Subjects were treated with one applicap of antibiotic and 1 cm length of clotrimazole ointment immediately in the affected eye and then were supplied by the VHWs with eight chloramphenicol applicaps and one tube of clotrimazole ointment and instructed to apply the remaining applicaps and ointment two more times the first day and three times a day for the following 2 days. The VHWs followed the subjects daily for 3 days to confirm compliance with the medication and to note any adverse events. After the ninth application of applicaps and ointment, a repeat fluorescein stain was performed to confirm healing of the abrasion. Compliance to medication was monitored through the collection of used empty applicaps and ointment tubes. The end point of prophylaxis was considered to be complete re‐epithelialisation of the cornea without evidence of infection at the site of the abrasion.

Results

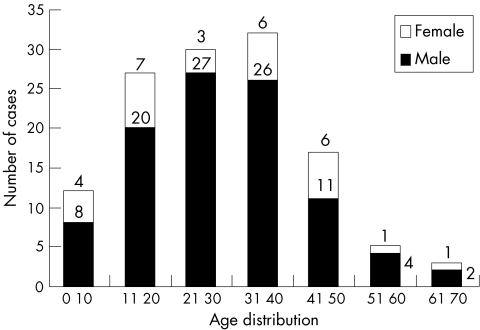

During the 12 month period, (October 2002 to September 2003), 273 individuals reported to the VHWs with an ocular injury. Of these, 126 were found to have a corneal abrasion. Eighty seven of these individuals (69%) reported within 6 hours of injury, and 122 (97%) in the first 18 hours (table 1). Of those injured, 24% were students and 43% were labourers or agricultural workers. Analysis of the age and sex distribution of the eligible cases revealed that the majority were in the teenage and early adult years with the preponderance of injuries occurring in males (fig 1). All of the 126 eligible cases of corneal abrasion treated with 1% chloramphenicol applicaps and 1% clotrimazole ointment healed without sequelae. There was not a single case of an adverse event or occurrence of a corneal ulcer reported during the course of the study period.

Table 1 Time interval between corneal abrasion and initiation of prophylactic treatment.

| Hours elapsed | No of patients with abrasion | |

|---|---|---|

| 0–6 hours | 87 | |

| 7–12 hours | 26 | |

| 13–18 hours | 9 | |

| 19–24 hours | 3 | |

| 25–48 hours | 1 | |

| Total | 126 |

Figure 1 Age and sex distribution of 126 cases of treated corneal abrasion.

Discussion

This study is part of a multicentre project carried out in three countries of South East Asia (Bhutan, Burma, and India) in collaboration with World Health Organization/South East Asia Regional Office in New Delhi, India and Aravind Eye Hospital in Madurai, India. The main objective of this three country trial is to test the efficacy of the three healthcare delivery systems in utilising village health workers to prevent corneal ulcers following ocular injury. Since the effectiveness of 1% chloramphenicol ointment in treating corneal abrasions and preventing bacterial corneal ulceration was demonstrated by the Bhaktapur Eye Study in Nepal2 and recently confirmed in Bhutan,3 this study in Burma was framed primarily to determine if fungal ulcers can be prevented following abrasions of the cornea. Antifungal prophylaxis (1% clotrimazole ointment) was administered, but for obvious reasons it was necessary to include antibiotic prophylaxis (1% chloramphenicol ointment) to the prevention regimen as well. Both medications were administered by existing VHWs who live and work in this defined population where two thirds of culture positive ulcers are known to be caused by fungal organisms, either pure or mixed with bacteria, and one third are caused by bacteria alone.

A population of 16 987 individuals living in three villages in Bago District was kept under daily surveillance by the VHWs for a period of 12 months. An extensive publicity campaign using mass communication media such as posters, pamphlets, video screening, radio messages, and group discussions was conducted to create awareness about the study. The effectiveness of the various publicity activities was verified randomly through awareness assessment surveys by the field supervisors every 3 months. The most effective publicity was found to be individual door to door contact with the VHWs during surveillance followed by the display of posters and notices in the villages.

During the 12 month period of the study, 273 ocular injuries were reported from the population of 16 987 (1071 per 100 000). Of these, 126 were cases of corneal abrasion (494 per 100 000). As in Nepal2 the incidence of corneal ulcers in the population was greater than the number of corneal abrasions reporting for treatment (710 per 100 000). Presumably this was because many patients who have abrasions consider them as trivial injuries, do not seek treatment, and quickly forget about them. In Nepal10 only 53% of the patients presenting with corneal ulcers could remember having a previous abrasion. This group may represent a previously unrecognised population at significant risk for corneal infection. Because of the active surveillance system in Burma, 69% of patients with corneal abrasions reported to a VHW within 0–6 hours of the injury and 97% within 18 hours. Since two thirds of all ulcers in Burma are fungal or fungi mixed with bacteria, and the incidence of corneal ulcers is 710 per 100 000, we should have seen at least 80 fungal ulcers out of a total of 120 ulcers in this population of 16 987. Instead, not a single case of corneal ulcer caused by either fungal or bacterial pathogens occurred in the study group during the 12 month period. Although there was not a control group for this study—that is, a group that received antibiotic ointment only, the absence of any fungal ulcers suggests that antifungal ointment is effective in preventing the development of fungal ulcers after traumatic corneal abrasions.

In Burma health care is provided through a highly organised system based at the village level. The high rates of patient response in reporting ocular injuries, even trivial corneal abrasions, and the excellent compliance in the use of study medication validates our hypothesis that existing healthcare workers in villages can prevent most corneal ulcers following abrasions by providing prophylactic treatment, even in an area where fungal ulcers are common. The high rate of compliance in reporting ocular injuries within 18 hours was mainly the result of the strict monitoring procedures of the study and the effect of health education on the study population. This is the first study to document that the incidence of fungal ulceration after corneal abrasion can be reduced by application of antifungal and antibiotic ointment in a population where fungal pathogens are cultured from the majority of corneal ulcers.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the World Health Organization/South East Asia Regional Office in New Delhi, and by material and technical resources from Aravind Medical Research Foundation, Aravind Eye Care System, and Lions Aravind Institute of Community Ophthalmology in Madurai. Logistic and human resources were provided by the Ministry of Health in Burma. Consultative support was provided by World Health Organization collaborating centres in San Francisco, New Delhi, and Madurai, and by the World Health Organization country office in Burma.

Abbreviations

VHWs - village health workers

References

- 1.Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Elya'ale at al Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull World Health Org 200482844–855. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Upadhyay M P, Karmacharya P C, Koirola S.et al The Bhaktapur Eye Study: ocular trauma and antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of corneal ulceration in Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol 200185388–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Getshen K, Srinivasan M, Upadhyay M P.et al Corneal ulceration in South East Asia. I: A model for the prevention of bacterial ulcers at the village level in rural Bhutan, Br J Ophthalmol 200690276–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tun Aung Kyaw A study of ocular trauma and corneal ulcer in Myanmar. Paper presented at an international workshop on corneal ulcer prevention, New Delhi, India: World Health Organization/South East Asia Regional Office, November, 1999

- 5. Ko K, Lwin K, Thaung , U , eds. Conquest of scourges in Myanmar. Yangon: Myanmar Academy of Medical Science, 2002;306,

- 6.World Health Organization Guidelines for the Management of Corneal Ulcer at Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Care health facilities in the South‐East Asia Region. SEA/Opthal/126. World Health Organization Regional Office for South‐East Asia 20041–36.

- 7.Hagan M, Wright E, Newman M.et al Causes of suppurative keratitis in Ghana. Br J Ophthalmol 1995791024–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srinivasan M, Gonzales C, George C.et al Epidemiology and aetiological diagnosis of corneal ulceration in Madurai, south India. Br J Ophthalmol 199781965–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitcher J P, Srinivasan M. Corneal ulceration in the developing world—a silent epidemic [editorial]. Br J Ophthalmol 199781622–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Upadhyay M, Karamcharya P, Koirala S.et al Corneal ulceration in Nepal: epidemiology, predisposing factors, and etiologic diagnosis. Am J Ophthalmol 199111192–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]