Abstract

Recent studies have revealed that oxidative stress has detrimental effects in several models of neurodegenerative diseases, including subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). However, how oxidative stress affects acute brain injury after SAH remains unknown. We have previously reported that overexpression of copper/zinc-superoxide dismutase (SOD1) reduces oxidative stress and subsequent neuronal injury after cerebral ischemia. In this study, we investigated the relationship between oxidative stress and acute brain injury after SAH using SOD1 transgenic (Tg) rats. SAH was produced by endovascular perforation in wild-type (Wt) and SOD1 Tg rats. Apoptotic cell death at 24 h, detected by a cell death assay, was significantly decreased in the cerebral cortex of the SOD1 Tg rats compared with the Wt rats. The mortality rate at 24 h was also significantly decreased in the SOD1 Tg rats. A hydroethidine study demonstrated that superoxide anion production after SAH was reduced in the cerebral cortex of the SOD1 Tg rats. Moreover, phosphorylation of Akt and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β), which are survival signals in apoptotic cell death, was more enhanced in the cerebral cortex of the SOD1 Tg rats after SAH using Western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry. We conclude that reduction in oxidative stress by SOD1 overexpression may attenuate acute brain injury after SAH via activation of Akt/GSK3β survival signaling.

Keywords: Akt, apoptosis, GSK3β, oxidative stress, SOD1, subarachnoid hemorrhage

Introduction

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) results in a high mortality rate, despite sophisticated medical management and neurosurgical techniques. Recent studies have emphasized the importance of acute brain injury after SAH (Cahill et al, 2006). In the clinical setting, most deaths occur within hours after onset of SAH (Broderick et al, 1994), and those patients who survive the initial hemorrhage and overcome vasospasms frequently suffer from persistent cognitive deficits, psychosocial impairments, and a decreased quality of life because of acute brain injury (Hütter et al, 2001). However, the underlying mechanisms of this injury after SAH are poorly understood. Apoptosis has been reported to be involved in acute brain injury after experimental SAH (Matz et al, 2000b, 2001; Park et al, 2004; Prunell et al, 2005) and in humans with SAH (Nau et al, 2002). These reports suggest that apoptotic cell death might be a therapeutic target in acute brain injury after SAH.

Oxidative stress plays important roles in the pathogenesis of acute brain injury after SAH (Matz et al, 2000a, 2001). We have reported that copper/zinc-superoxide dismutase (SOD1) is a crucial endogenous enzyme responsible for eliminating superoxide and that overexpression of SOD1 reduces cell injury after SAH (Matz et al, 2000a). However, the mechanisms of SOD1 protection against SAH remain unclear. In cerebral ischemia, the neuroprotective role of SOD1 is partly mediated by Akt activation (Noshita et al, 2003). The serine-threonine kinase, Akt, plays an important role in the cell death/survival pathway (Datta et al, 1997). It is downstream of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway and is activated by phosphorylation at Ser473 residue (Alessi et al, 1996). Activated Akt promotes cell survival and suppresses apoptosis by phosphorylation and inhibition of several downstream substrates, including glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) (Cross et al, 1995), a mechanism by which neurons are proposed to become resistant to apoptotic stimuli (Hetman et al, 2000). This Akt survival pathway is the focus for clarifying the machinery of apoptotic neuronal death in several models of neurodegenerative diseases, including cerebral ischemia, traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, and SAH (Endo et al, 2006a, 2006b; Noshita et al, 2001, 2002; Yu et al, 2005). This inspired us to investigate the relationship between SOD1 and the Akt pathway in acute brain injury after SAH. In this study, we address this issue by examining apoptotic cell death, superoxide production, and phosphorylation of Akt/GSK3β after SAH, using both wild-type (Wt) and SOD1 transgenic (Tg) rats.

Materials and methods

SOD1 Tg Rats

All animals were treated in accordance with Stanford University guidelines and the animal protocols approved by Stanford University’s Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care. Heterozygous SOD1 Tg rats with a Sprague-Dawley background, carrying human SOD1 genes, were derived from the founder stock and further bred with Wt Sprague-Dawley rats to generate heterozygous rats as previously described by our group (Chan et al, 1998). The phenotype of the SOD1 Tg rats was identified by isoelectric focusing gel electrophoresis. There were no observable phenotypic differences in brain vasculature between the Tg rats and Wt littermates.

SAH Rat Model

SAH was produced in male Sprague-Dawley rats (270 to 300 g) using an endovascular perforation method (Bederson et al, 1995). The rats were anesthetized with 2.0% isoflurane in 70% nitrous oxide and 30% oxygen using a face mask. Rectal temperature was controlled at 37°C during surgery. The left common carotid artery was isolated and a 3–0 monofilament nylon suture was inserted through the internal carotid artery to perforate this artery at the bifurcation of the anterior and middle cerebral arteries. SAH was confirmed in each rat at autopsy. Sham-operated rats underwent identical procedures except the perforation. The animals were maintained in an air-conditioned room at 20°C with ad libitum access to food and water before and after surgery.

Physiological Dataand Mortality

After anesthesia, the femoral artery was exposed and catheterized with a PE-50 catheter to allow measurement of blood gas values, blood pH, and continuous recording of mean arterial blood pressure (MABP). Mortality was calculated 24 h after SAH.

Cell Death Assay

For quantification of DNA fragmentation, which indicates apoptotic cell death, we used a commercial enzyme immunoassay to determine cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragments (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Fresh brain tissue was taken and protein extraction of the cytosolic fraction was performed as described (Fujimura et al, 1998). A cytosolic volume containing 20 μg of protein was used for the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, following the manufacturer’s protocol.

In Situ Detection of Superoxide Anion Production

Early production of superoxide anions (O2−) during SAH was investigated with the use of hydroethidine (HEt) as previously described (Murakami et al, 1998). HEt is diffusible into the central nervous system parenchyma after an intravenous injection and is selectively oxidized to ethidium by O2−. HEt solution (200 μl; 1 mg/mL in 1% dimethylsulfoxide with saline) was administered intravenously 15 min before perforation. The animals were perfused with 10 U/ml heparin saline and subsequently with 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline 1 h after surgery. The brains were sectioned at 50 μm on a vibratome. Subsequently, the slides were covered with 4′,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and observed with a fluorescent microscope.

Western Blot Analysis

Fresh brain tissue was removed and cut into 1.0-mm coronal slices using a brain matrix (Zivic Laboratories Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Bilateral cerebral cortices (2.0 to 6.0 mm posterior to bregma) were quickly dissected under a microscope and used as samples. Whole-cell protein extraction was performed as described (Noshita et al, 2001). Equal amounts of the samples were loaded per lane. The primary antibodies were 1:2000 dilution of the antibody against Akt and phospho-Akt (Ser473), 1:1000 dilution of the antibody against GSK3β and phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) (both from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), and 1:10000 dilution of the antibody against β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Western blots were performed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated immunoglobulin G (IgG) using enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (Amersham International, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Immunohistochemistry

Anesthetized animals were perfused with 10 U/ml heparin saline and subsequently with 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. The brains were sectioned at 50 μm with a vibratome. The same tissue sections that were used for Western analysis were used for immunohistochemistry. The sections were incubated with the antibody against phospho-Akt (Ser473) (Cell Signaling Technology) and an antibody against phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), each at a 1:50 dilution. Immunohistochemistry was performed via the avidin-biotin technique, followed by methyl green staining. To confirm the specificity of the antibody, immunohistochemistry with the antiphospho-Akt antibody preabsorbed with the phospho-Akt (Ser473) peptide (Cell Signaling Technology) was also performed.

Immunofluorescent Double Labeling Staining

For double staining of phospho-Akt (Ser473) and phospho-GSK3β (Ser9), the sections were incubated with a mouse antibody against phospho-Akt (Cell Signaling Technology) at the dilution of 1:50, followed by a Texas Red-conjugated IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) at the dilution of 1:200. The sections were then incubated with a rabbit antibody against phospho-GSK3β (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at the dilution of 1:50, followed by a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at a dilution of 1:200. For double staining of phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) and neuron-specific nuclear protein (NeuN), the sections were incubated with a rabbit antibody against phospho-GSK3β (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at the dilution of 1:50, followed by a Texas Red-conjugated IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at a dilution of 1:200. The sections were then incubated with the anti-NeuN Alexa Fluor-conjugated antibody (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA) at the dilution of 1:200, then covered with VECTASHIELD mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories) and observed with a fluorescent microscope.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Comparisons among multiple groups were performed with a one-way analysis of variance, followed by Scheffé's post hoc analysis (SigmaStat software; Jandel Corporation, San Rafael, CA, USA). Comparisons between two groups were achieved with Student’s unpaired t-test. Significant differences between the groups regarding mortality were analyzed using a χ2 test. The data are expressed as mean ± s.d. and significance was accepted with P < 0.05.

Results

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Physiological Data

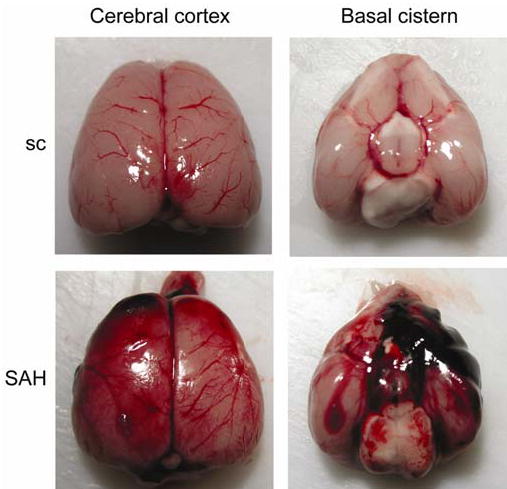

In our model, SAH was diffusely distributed from the basal cistern to the cerebral cortex (Figure 1). The whole brains, seen grossly, were edematous after SAH compared with the sham-operated brains. The grade of SAH, which was confirmed at autopsy, was similar between the Wt and SOD1 Tg rats. The mean values of pH, PaO2, PaCO2, and body temperature measured just after SAH are presented in the Table. No significant changes were observed in any physiological parameters between the Wt and SOD1 Tg rats. There were significant increases in MABP immediately after SAH, by 15.0 % of baseline values in the Wt rats and by 14.4 % of baseline values in the SOD1 Tg rats (n = 4 for each group, P < 0.05). No significant difference was seen in this increasing rate of MABP between the two groups. It approached baseline values within 5 min after SAH in both groups, which was consistent with an earlier report (Prunell et al, 2003).

Figure 1.

Representative photographs of rat brains after surgery. In the sham-operated rats (sc), there is no blood clotting throughout the brain. In the SAH group, clots are diffuse throughout the brain surface, especially around the bifurcation of the anterior and middle cerebral arteries in the basal cistern.

Table.

Physiological data during SAH

| Parameter | Wt rats | SOD1 Tg rats |

|---|---|---|

| Blood gas (n = 5) | ||

| pH | 7.37 ± 0.05 | 7.41 ± 0.05 |

| PaO2 | 143.7 ± 18.8 | 133.1 ± 10.5 |

| PaCO2 | 36.3 ± 4.5 | 34.8 ± 3.3 |

| Body temperature | 36.6 ± 0.8 | 37.1 ± 0.6 |

| MABP (n = 4) | ||

| Before | 91.8 ± 16.5 | 78.3 ± 14.0 |

| Immediately after | 105.5 ± 19.9 | 89.5 ± 16.8 |

| 1 min | 95.3 ± 14.9 | 85.3 ± 15.5 |

| 5 min | 82.3 ± 4.5 | 77.3 ± 12.8 |

| 10 min | 84.3 ± 7.0 | 72.5 ± 11.5 |

All data are expressed as mean ± s.d.

Cell Death and Mortality Rate after SAH in Wt and SOD1 Tg Rats

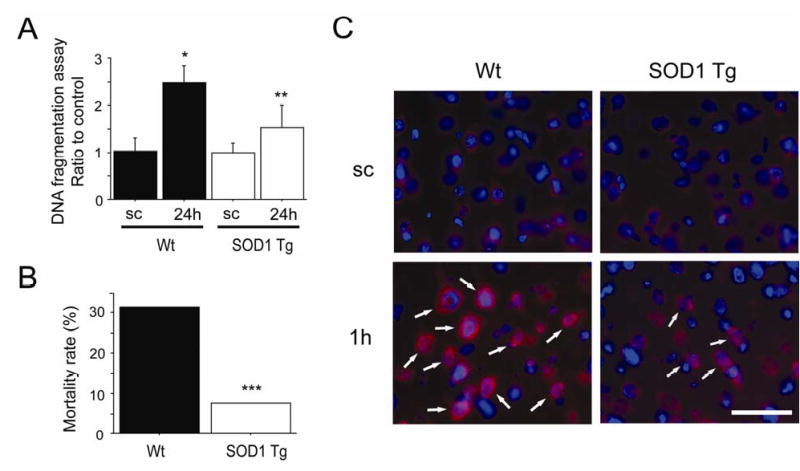

To investigate apoptotic cell death in acute brain injury after SAH, DNA fragmentation was analyzed with a commercial enzyme immunoassay (cell death assay) (Figure 2A). In the Wt rats, the cell death assay revealed that DNA fragmentation was significantly increased at 24 h compared with the sham-operated rats. DNA fragmentation in the SOD1 Tg rats was significantly decreased at 24 h compared with the Wt rats at the same time point. The mortality rate at 24 h seems to include death caused by acute brain injury after SAH (Park et al, 2004), because vasospasm occurs during the later phase after SAH (Kamii et al, 1999). This mortality rate was 31.4% for the Wt rats (11 of 35) and 7.69% for the SOD1 Tg rats (2 of 26) (Figure 2B). Statistical analysis showed that the mortality rate for the SOD1 Tg rats was significantly decreased. These results indicate that SOD1 overexpression reduced apoptotic cell death in the cerebral cortex and the mortality rate 24 h after SAH.

Figure 2.

Apoptotic cell death, mortality and production of O2− after SAH. (A) Analysis with a commercial cell death detection kit revealed that apoptotic-related DNA fragmentation in the Wt rats significantly increased at 24 h compared with the sham-operated rats (sc) (n = 4, *P = 0.0006). In a comparison between the two groups, DNA fragmentation at 24 h was significantly decreased in the SOD1 Tg rats (n = 4, **P = 0.0169). (B) The mortality rate at 24 h was significantly decreased in the SOD1 Tg rats (***P = 0.0302). (C) Fluorescent double staining of oxidized HEt signals (red) and DAPI (blue) after SAH. Slight O2− production was seen in the cytosol of the sham-operated control brains (sc) in both groups. One hour after SAH, enhanced vesicular signals were observed in the cerebral cortex of the Wt rats (arrows), but were markedly decreased in the SOD1 Tg rats. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

Production of O2− after SAH in the Wt and SOD1 Tg rats

To confirm whether free radical production was increased after SAH, we examined O2− production using HEt as described previously (Murakami et al, 1998). O2− production was shown by oxidized HEt signals in the cytosol of the cerebral cortex in both the sham-operated Wt and sham-operated SOD1 Tg rats, and no conspicuous difference was observed between them (Figure 2C). However, enhanced vesicular signals were observed in the cerebral cortex at 1 h in the Wt rats, but were markedly decreased in the SOD1 Tg rats. These results suggest that O2− production was accelerated by SAH and was inhibited by SOD1 overexpression.

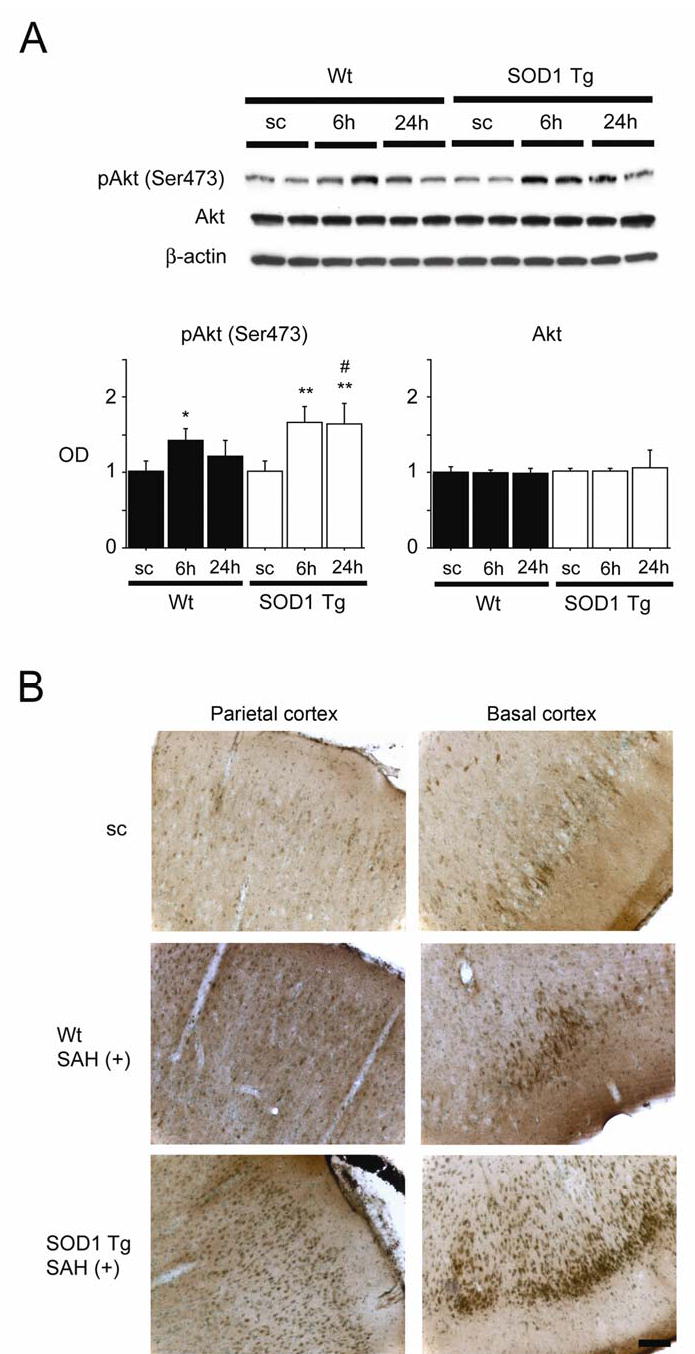

Phosphorylation of Akt after SAH

We then investigated whether SAH affects the phosphorylation of Akt. Bands of phospho-Akt (Ser473) and Akt were observed at 60 kDa with Western blot analysis (Figure 3A). Immunoreactivity of phospho-Akt was significantly increased at 6 h in the Wt rats. In the SOD1 Tg rats, the increase in the phospho-Akt level was more prominent and persistent and a significant difference was seen at 6 and 24 h compared with the control brain samples. In the comparison between the two groups, phospho-Akt was significantly increased at 24 h in the SOD1 Tg rats. Immunoreactivity of Akt showed no prominent change after SAH in either group. An immunohistochemistry study showed slight immunoreactivity of phospho-Akt (Ser473) in each cortical region, including the parietal cortex and basal cortex, of the control brains (Figure 3B). This immunoreactivity became stronger at 24 h in the parietal and basal cortices in both groups. In the SOD1 Tg rats, phospho-Akt expression at 24 h was more prominent than in the Wt rats in the parietal and basal cortices. These results indicate that phosphorylation of Akt is accelerated after SAH and that SOD1 overexpression may contribute to enhanced Akt phosphorylation.

Figure 3.

Changes in phosphorylation of Akt (pAkt) after SAH. (A) Western blot analysis showed that pAkt (Ser473) expression in the Wt rats increased significantly at 6 h compared with the sham-operated control (sc) samples (n = 4, *P < 0.05). In the SOD1 Tg rats, pAkt was significantly increased at 6 and 24 h compared with the sham-operated control samples (n = 4, **P < 0.01). In a comparison between the two groups, pAkt was significantly increased at 24 h in the SOD1 Tg rats (n = 4, #P < 0.05). There was no prominent change in Akt. The results of a β-actin analysis are shown as an internal control. OD indicates optical density. (B) Immunohistochemistry for pAkt (Ser473) showed that immunoreactivity became much stronger 24 h after SAH in the parietal and basal cortices of the SOD1 Tg rats compared with the Wt rats. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

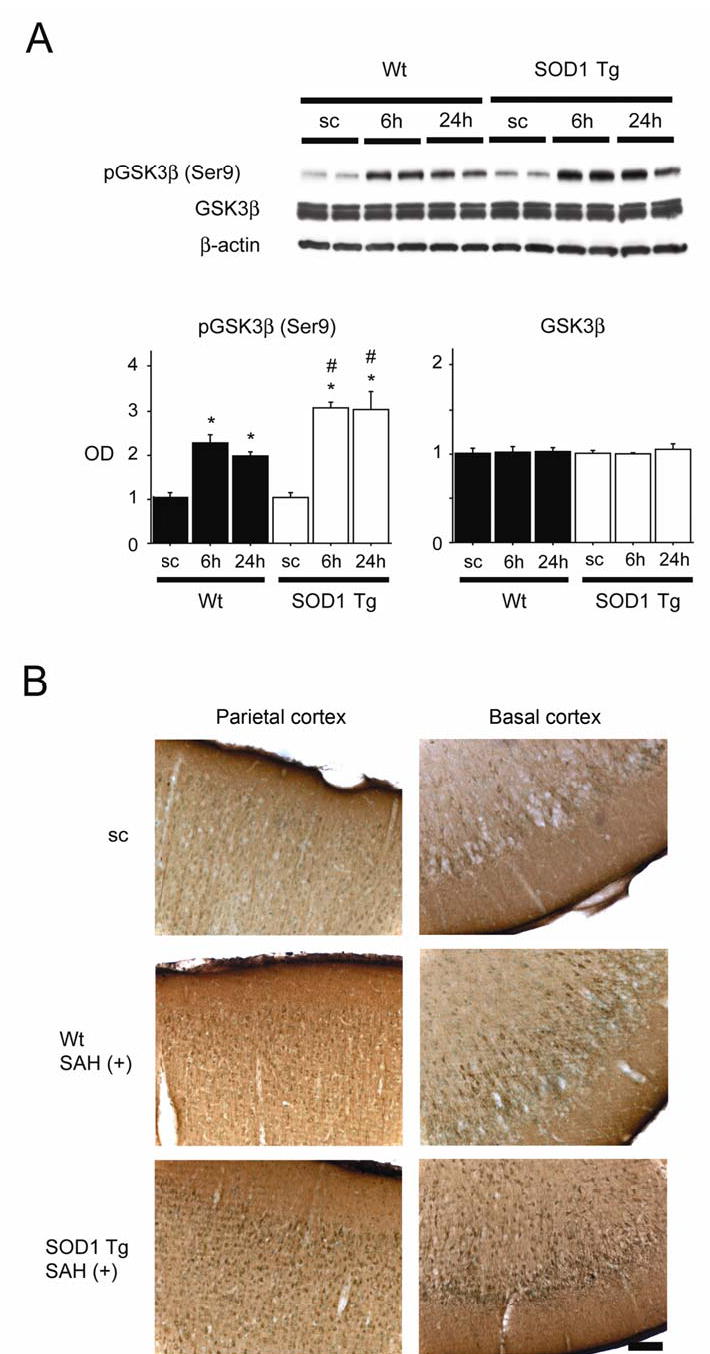

Phosphorylation of GSK3β after SAH

Since phospho-Akt functions through phosphorylation and inhibition of GSK3β (Cross et al, 1995), we further examined the phosphorylation of GSK3β. Bands of phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) and GSK3β were observed at 46 kDa in Western blot analysis (Figure 4A). Immunoreactivity of phospho-GSK3β was significantly increased at 6 and 24 h in both groups. In the comparison between the two groups, phospho-GSK3β was significantly increased at 6 and 24 h in the SOD1 Tg rats. Immunoreactivity of GSK3β showed no prominent change in either group. An immunohistochemistry study showed slight immunoreactivity of phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) in each cortical region, including the parietal cortex and basal cortex of the control brains (Figure 4B). This immunoreactivity became stronger at 24 h in the parietal and basal cortices in both groups and in the SOD1 Tg rats, phospho-GSK3β expression at 24 h was more prominent than in the Wt rats. These results indicate that phosphorylation of GSK3β is accelerated after SAH and that SOD1 overexpression may contribute to enhanced GSK3β phosphorylation.

Figure 4.

Changes in phosphorylation of GSK3β (pGSK3β) after SAH. (A) Western blot analysis showed that pGSK3β (Ser9) expression in both the Wt and SOD1 Tg rats increased significantly at 6 and 24 h compared with the sham-operated control (sc) samples (n = 4, *P < 0.0001). In a comparison between the two groups, pGSK3β was significantly increased at 6 and 24 h in the SOD1 Tg rats (n = 4, #P < 0.005). There was no prominent change in GSK3β. The results of a β-actin analysis are shown as an internal control. OD indicates optical density. (B) Immunohistochemistry for pGSK3β (Ser9) showed that immunoreactivity became much stronger at 24 h in the parietal and basal cortices of the SOD1 Tg rats compared with the Wt rats. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

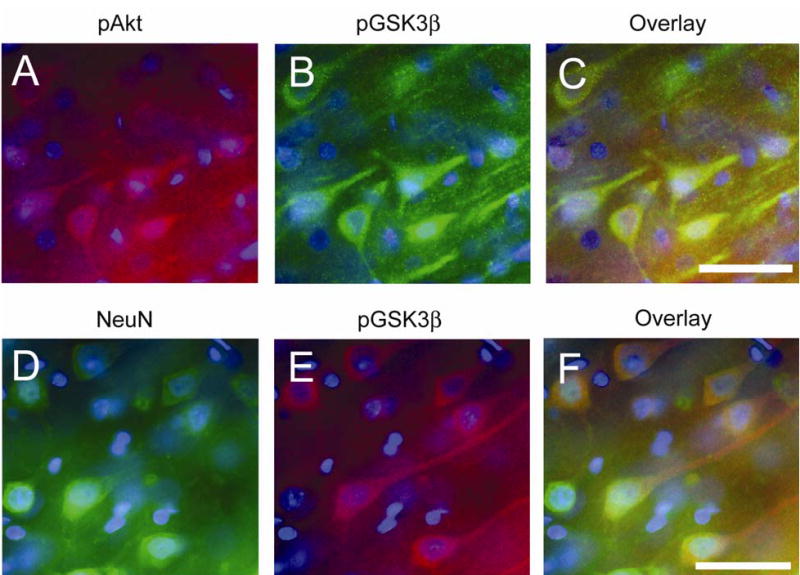

Colocalization of phospho-Akt and phospho-GSK3β, and phospho-GSK3β and NeuN

We performed a double immunofluorescent study to investigate what type of cells showed activation of Akt/GSK3β signaling. This study demonstrated that phospho-Akt-positive cells colocalized with phospho-GSK3β-positive cells in the cerebral cortex 6 h after SAH (Figure 5A-C). Moreover, phospho-GSK3β-positive cells colocalized mainly with neurons at the same time point (Figure 5D-F). These results suggest that phosphorylation of both Akt and GSK3β occurred mainly in neurons after SAH.

Figure 5.

Double immunofluorescent staining of phosphorylation of Akt (pAkt) (red) and of GSK3β (pGSK3β) (green), and NeuN (green) and pGSK3β (red) in the cerebral cortex 6 h after SAH. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). pAkt-positive cells (A) and pGSK3β-positive cells. (B) were observed in the cerebral cortex. (C) An overlapped image shows that pAkt-positive cells colocalized with pGSK3β-positive cells. (D) NeuN-positive cells reveal neurons in the cerebral cortex. (E) pGSK3β immunohistochemistry shows pGSK3β-positive cells in the same view. (F) An overlapped image shows that pGSK3β-positive cells colocalized with neurons. Scale bars represent 50 μm.

Discussion

Antioxidant enzymes play a major role in the mechanism by which cells counteract the deleterious effects of reactive oxygen species. SOD1 is one of these antioxidant enzymes and we have reported that SOD1 overexpression has a protective effect against cerebral ischemia (Noshita et al, 2003), spinal cord injury (Yu et al, 2005) and SAH (Matz et al, 2000a). However, the protective mechanisms of SOD1 overexpression against SAH are largely unknown. Based on the results of the present study, we propose that the reduction in oxidative stress by SOD1 overexpression attenuates acute brain injury after SAH via activation of Akt/GSK3β survival signaling.

Many factors, such as acute cerebral ischemia (Park et al, 2004), subarachnoid blood toxicity (Matz et al, 2000a), or acute vasospasm (Bederson et al, 1998), are involved in the complicated mechanism of acute brain injury after SAH. These factors induce apoptotic cell death after SAH (Matz et al, 2000b; Park et al, 2004; Prunell et al, 2005), which might be the therapeutic target for clinical SAH. SOD1 Tg animals may help us understand these complicated mechanisms of acute brain injury after SAH. We have reported that cell injury caused by SAH was reduced by SOD1 overexpression, though apoptotic cell death was not attenuated (Matz et al, 2000a). However, apoptotic cell death detected by a cell death assay was decreased in the SOD1 Tg animals in the present study. This discrepancy might depend on the model of SAH. We injected 50 μl of autologous blood into the subarachnoid space to examine subarachnoid blood toxicity in our previous study (Matz et al, 2000a). In the present study, however, we used a perforation model of SAH (Bederson et al, 1995), which theoretically mimics the mechanism of clinical SAH. In this model, the mechanism of brain injury might be more complicated. After perforation, blood is rapidly distributed throughout the brain surface, and intracranial pressure is rapidly and dramatically increased, resulting in acute global ischemia. A subarachnoid blood clot itself induces oxidative stress and cell injury (Matz et al, 2000a), which might be amplified by this acute global ischemia. To assess the degree of oxidative stress after SAH, we used a HEt technique that can detect O2− production in vivo (Murakami et al, 1998). O2− plays a key role in the oxidative chain reaction, producing a highly reactive oxidant. O2− production was observed after SAH (Mori et al, 2001), as well as after cerebral ischemia (Murakami et al, 1998), which can cause apoptotic neuronal injury. Reduction in O2− production caused by SOD1 overexpression decreased apoptotic neuronal death after cerebral ischemia (Noshita et al, 2003). In the present study, O2− production detected by the HEt study 1 h after SAH was prominently inhibited in the SOD1 Tg rats compared with the Wt rats. Thus, this decrease in oxidative stress might lead to a decrease in acute brain injury after SAH, which would be detected by the extent of apoptotic cell death and the mortality rate at 24 h in the SOD1 Tg rats. In addition, the volume of the SAH is an important factor affecting outcome (Prunell et al, 2003). Although we observed no differences in hemorrhagic volume between the Wt and the SOD1 Tg rats, these observations need to be further confirmed by additional quantitative measurements, which would allow us to better understand the oxidative mechanisms involved in this model.

Akt plays a crucial role in the cell death/survival pathway through several different downstream targets including GSK3β (Cross et al, 1995). We have reported a temporal increase in phospho-Akt after cerebral ischemia (Endo et al, 2006a; Noshita et al, 2001), traumatic brain injury (Noshita et al, 2002), spinal cord injury (Yu et al, 2005), and SAH (Endo et al, 2006b). These studies suggest that relatively mild insults upregulate Akt phosphorylation, while severe damage downregulates it (Noshita et al, 2001). GSK3β phosphorylation at Ser9 is accelerated in the neurons as a downstream target of Akt, and activation of the Akt/GSK3β pathway mediates neuronal survival after cerebral ischemia (Endo et al, 2006a) or SAH (Endo et al, 2006b). Therefore, the Akt/GSK3β survival pathway seems to play a significant role in the neuronal death machinery of neurodegenerative diseases. In this study, Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 and GSK3β phosphorylation at Ser9 were increased in the parietal cortex and basal cortex, after SAH in both the Wt and the SOD1 Tg rats. The double immunofluorescent study showed that this phosphorylation occurred in cortical neurons. In the Wt rats, phosphorylation of these proteins peaked at 6 h and tended to decrease thereafter. In contrast, phosphorylation of these proteins was more prominent and continued to increase up to 24 h after SAH in the SOD1 Tg rats. These results suggest that SOD1 overexpression modulates phosphorylation of both Akt and GSK3β after SAH. The oxidative stress caused by SAH might switch on the phosphorylation of these proteins, because oxidative stress is one of the triggers for Akt activation (Noshita et al, 2003). However, excessive stress might result in dephosphorylation of these proteins in the Wt rats. As a result, protection by the Akt/GSK3β pathway would be overcome and acute brain injury would occur. In the SOD1 Tg rats, reduction in oxidative stress by SOD1 overexpression might prevent dephosphorylation of these proteins, resulting in continuous activation of the Akt/GSK3β survival pathway and decreased subsequent apoptotic cell death. In addition to the cell survival pathway, SOD1 overexpression modulates cell death pathways, such as the mitochondrial pathway, after cerebral ischemia (Fujimura et al, 2000), which may contribute to protective mechanisms against SAH. Thus, determining how SOD1 overexpression modulates the cell death/survival pathway could clarify the detailed mechanisms of acute brain injury after SAH.

In summary, this study suggests that oxidative stress plays a significant role in acute brain injury after SAH, and that the neuroprotection of SOD1 is partly mediated by activation of the Akt/GSK3β survival pathway. Reducing oxidative stress, thereby activating the survival pathway, could be a therapeutic target for acute brain injury after SAH in a clinical situation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Liza Reola, Bernard Calagui, and Trisha Crandall for technical assistance, Cheryl Christensen for editorial assistance, and Elizabeth Hoyte for figure preparation.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants P50 NS14543, RO1 NS25372, RO1 NS36147, and RO1 NS38653.

References

- Alessi DR, Andjelkovic M, Caudwell B, Cron P, Morrice N, Cohen P, et al. Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. EMBO J. 1996;15:6541–6551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bederson JB, Germano IM, Guarino L. Cortical blood flow and cerebral perfusion pressure in a new noncraniotomy model of subarachnoid hemorrhage in the rat. Stroke. 1995;26:1086–1091. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.6.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bederson JB, Levy AL, Ding WH, Kahn R, Diperna CA, Jenkins AL, III, et al. Acute vasoconstriction after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:352–360. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199802000-00091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick JP, Brott TG, Duldner JE, Tomsick T, Leach A. Initial and recurrent bleeding are the major causes of death following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1994;25:1342–1347. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.7.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill WJ, Calvert JH, Zhang JH. Mechanisms of early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600283. [Epub ahead of print--doi:10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600283] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PH, Kawase M, Murakami K, Chen SF, Li Y, Calagui B, et al. Overexpression of SOD1 in transgenic rats protects vulnerable neurons against ischemic damage after global cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8292–8299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08292.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross DAE, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B [Letter] Nature. 1995;378:785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, et al. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 1997;91:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo H, Nito C, Kamada H, Nishi T, Chan PH. Activation of the Akt/GSK3β signaling pathway mediates survival of vulnerable hippocampal neurons after transient global cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006a doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600303. [Epub ahead of print--doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600303] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo H, Nito C, Kamada H, Yu F, Chan PH. Akt/GSK3β survival signaling is involved in acute brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Stroke. 2006b doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000229888.55078.72. [Epub ahead of print--doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000229888.55078.72] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura M, Morita-Fujimura Y, Murakami K, Kawase M, Chan PH. Cytosolic redistribution of cytochrome c after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:1239–1247. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199811000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura M, Morita-Fujimura Y, Noshita N, Sugawara T, Kawase M, Chan PH. The cytosolic antioxidant copper/zinc-superoxide dismutase prevents the early release of mitochondrial cytochrome c in ischemic brain after transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2817–2824. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02817.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetman M, Cavanaugh JE, Kimelman D, Xia Z. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3β in neuronal apoptosis induced by trophic withdrawal. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2567–2574. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-07-02567.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hütter BO, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I, Gilsbach JM. Health-related quality of life after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: impacts of bleeding severity, computerized tomography findings, surgery, vasospasm, and neurological grade. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:241–251. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.94.2.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamii H, Kato I, Kinouchi H, Chan PH, Epstein CJ, Akabane A, et al. Amelioration of vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage in transgenic mice overexpressing CuZn-superoxide dismutase. Stroke. 1999;30:867–872. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matz PG, Copin J-C, Chan PH. Cell death after exposure to subarachnoid hemolysate correlates inversely with expression of CuZn-superoxide dismutase. Stroke. 2000a;31:2450–2458. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matz PG, Fujimura M, Chan PH. Subarachnoid hemolysate produces DNA fragmentation in a pattern similar to apoptosis in mouse brain. Brain Res. 2000b;858:312–319. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matz PG, Fujimura M, Lewen A, Morita-Fujimura Y, Chan PH. Increased cytochrome c-mediated DNA fragmentation and cell death in manganese-superoxide dismutase-deficient mice after exposure to subarachnoid hemolysate. Stroke. 2001;32:506–515. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.2.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Nagata K, Town T, Tan J, Matsui T, Asano T. Intracisternal increase of superoxide anion production in a canine subarachnoid hemorrhage model. Stroke. 2001;32:636–642. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.3.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K, Kondo T, Kawase M, Li Y, Sato S, Chen SF, et al. Mitochondrial susceptibility to oxidative stress exacerbates cerebral infarction that follows permanent focal cerebral ischemia in mutant mice with manganese superoxide dismutase deficiency. J Neurosci. 1998;18:205–213. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00205.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nau R, Haase S, Bunkowski S, Brück W. Neuronal apoptosis in the dentate gyrus in humans with subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral hypoxia. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:329–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noshita N, Lewén A, Sugawara T, Chan PH. Evidence of phosphorylation of Akt and neuronal survival after transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1442–1450. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200112000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noshita N, Lewén A, Sugawara T, Chan PH. Akt phosphorylation and neuronal survival after traumatic brain injury in mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;9:294–304. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noshita N, Sugawara T, Lewén A, Hayashi T, Chan PH. Copper-zinc superoxide dismutase affects Akt activation after transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Stroke. 2003;34:1513–1518. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000072986.46924.F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Yamaguchi M, Zhou C, Calvert JW, Tang J, Zhang JH. Neurovascular protection reduces early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2004;35:2412–2417. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000141162.29864.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prunell GF, Mathiesen T, Diemer NH, Svendgaard N-A. Experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage: subarachnoid blood volume, mortality rate, neuronal death, cerebral blood flow, and perfusion pressure in three different rat models. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:165–176. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200301000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prunell GF, Svendgaard N-A, Alkass K, Mathiesen T. Delayed cell death related to acute cerebral blood flow changes following subarachnoid hemorrhage in the rat brain. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:1046–1054. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.6.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Sugawara T, Maier CM, Hsieh LB, Chan PH. Akt/Bad signaling and motor neuron survival after spinal cord injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:491–499. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]