Abstract

Gene therapy as a treatment modality for pulmonary disorders has attracted significant interest over the past decade. Since the initiation of the first clinical trials for cystic fibrosis lung disease using recombinant adenovirus in the early 1990s, the field has encountered numerous obstacles including vector inflammation, inefficient delivery, and vector production. Despite these obstacles, enthusiasm for lung gene therapy remains high. In part, this enthusiasm is fueled through the diligence of numerous researchers whose studies continue to reveal great potential of new gene transfer vectors that demonstrate increased tropism for airway epithelia. Several newly identified serotypes of adeno-associated virus have demonstrated substantial promise in animal models and will likely surface soon in clinical trials. Furthermore, an increased understanding of vector biology has also led to the development of new technologies to enhance the efficiency and selectivity of gene delivery to the lung. Although the promise of gene therapy to the lung has yet to be realized, the recent concentrated efforts in the field that focus on the basic virology of vector development will undoubtedly reap great rewards over the next decade in treating lung diseases.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, viral vectors, lung, airway epithelium, AAV, adenovirus, α-1-antitrypsin deficiency

INTRODUCTION

Gene therapy by definition uses nucleic acid (DNA or RNA) as a drug delivery vehicle by which to facilitate the expression of therapeutic proteins. Gene therapy approaches can be broadly classified into three mechanistically distinct categories: (a) gene addition (also sometimes called gene replacement), (b) gene reprogramming, and (c) gene repair. Gene addition, currently the most commonly used approach and the only clinically tested method for gene therapy, seeks to add a copy of a corrected gene to overcome an inherited genetic mutation. Advantages of gene addition for the treatment of inherited disorders include its simplicity, whereas disadvantages often include a lack of controlled gene expression. For less complex disorders, gene replacement strategies are the most obvious choice. However, for disorders with a more complex pathophysiology in which the gene product may require controlled cell-specific expression or disorders with a dominant phenotype, gene addition approaches are less optimal. A second approach that begins to address some of the limitations of gene replacement approaches is gene reprogramming. This approach seeks to reprogram (or correct) defective portions of endogenously encoded mutant RNA transcripts for a given gene (1). Although this approach also expresses additional genetic material within cells, the end result is correction (or reprogramming) of endogenous mutant gene transcripts, as opposed to the expression of an additional intact functional gene transcript. Advantages to this approach include the fact that a corrected protein product will only be reconstituted in those cells that express the mutant target gene. Moreover, in situations where a mutant protein gives rise to a dominant phenotype, RNA reprogramming has both theoretical and practical advantages. Disadvantages to this approach include the presently inefficient nature of the reprogramming events. Although considerably more technically challenging than gene addition or reprogramming approaches, gene repair is considered the Holy Grail of gene therapy for inherited disorders (2). In contrast to adding copies of a gene to cells, gene repair seeks to correct mutant sequences in the genomic DNA. Although theoretical advantages to this approach are apparent, the efficiency of gene repair techniques at present is extremely low, rendering clinical application unrealistic at this time.

Critical to the success of any gene therapy approach is having the appropriate tools needed to facilitate genetic modification. The most successful tools used to date include various forms of recombinant viruses that have been engineered to be replication defective while carrying various therapeutic genes. Although the field has made significant progress in this area, fooling Mother Nature has turned out to be more difficult than previously anticipated. Some of the most challenging obstacles include immunologic reactions to the vector, inefficient gene transfer, and targeting gene expression to the appropriate cell types required to reverse pathology. The most widely studied lung disease targets for gene therapy thus far include cystic fibrosis, α–1-antitrypsin deficiency, and surfactant deficiency, as well as acquired disorders including lung cancers and acute lung injury. This review attempts to address several pertinent areas for gene therapy of inherited lung diseases while concentrating on cystic fibrosis as a model disease application.

INHERITED LUNG DISEASE TARGETS FOR GENE THERAPY

Cystic Fibrosis

As the most common inherited disease in the Caucasian population, cystic fibrosis (CF) has been one of the most extensively studied genetic diseases in gene therapy. Genetic abnormalities in CF are the result of a defective epithelial chloride channel called the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (3). The most severely affected organ includes the lung in which chronic bacterial infections with opportunistic bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa leads to a progressive loss in lung function and ultimately death (3). Hence, the lung is presently the major initial target for gene therapy of CF. Although the pathophysiology of CF lung disease still remains controversial (4), it is fairly well accepted that the properties of surface airway fluid and mucous, which are important in protecting the airway epithelium from invading bacteria, are compromised when CFTR is defective (5). The pathoprogression of airway disease in CF appears to involve changes in the viscosity and/or ionic properties of the airway surface fluid and mucous layer leading to reduced clearance of inhaled bacteria and/or impaired antibacterial killing, respectively (4). The lack of an animal model for CF that reproduces the human lung phenotype has also hindered progress in answering pathophysiologic questions that are fundamental to gene therapy for this disorder. Unfortunately, CFTR knockout mice do not acquire spontaneous lung infections as seen in the human condition, but rather, have severe intestinal defects (6). Because of this basic difference, the testing of gene therapy approaches for CF have relied heavily on molecular endpoints for complementation such as chloride transport. Without a clear understanding of how chloride transport is linked to disease progression, the use of such surrogate endpoints in human clinical trials has significant limitations. Numerous viral and non-viral vectors have been evaluated as vehicles to deliver the CFTR cDNA to the lung in animal models and in clinical trials. Because this review focuses on cystic fibrosis as a disease model for discussing these gene therapy applications, specific examples are explored in detail in subsequent sections.

α–1-Antitrypsin Deficiency

A second attractive target for gene therapy to the lung includes α–1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency, an autosomal-recessive inherited disease leading to panacinar emphysema of the lung and cirrhosis of the liver. AAT, which is normally synthesized by the liver and circulates throughout the body, provides important protection against proteases such as neutrophil elastase. Although abnormalities in the liver associated with this genetic disease remain somewhat obscure, the increased neutrophil elastase activity results in a prolonged, recurrent digestion of the extracellular matrix of the lung and causes the most life-threatening pathology of this disease (7). Hence, the lung is considered a highly relevant target for gene therapy of AAT deficiency and has been tested in animal models using recombinant adenovirus (8) and DNA/liposome complexes (9). However, because AAT freely circulates throughout the body, gene therapy approaches targeting both the endogenous sites of production in the liver (10) and ectopic sites such as muscle (11) have also been evaluated in animal models. A clinical trial for AAT deficiency, directed by Flotte, proposes to use AAV-2-based intramuscular delivery and has recently obtained RAC approval. FDA approval is currently ongoing and the trial is slated to begin in late fall of 2002 (T. Flotte, personal communication).

GENE THERAPY VECTORS

Recombinant Adenovirus

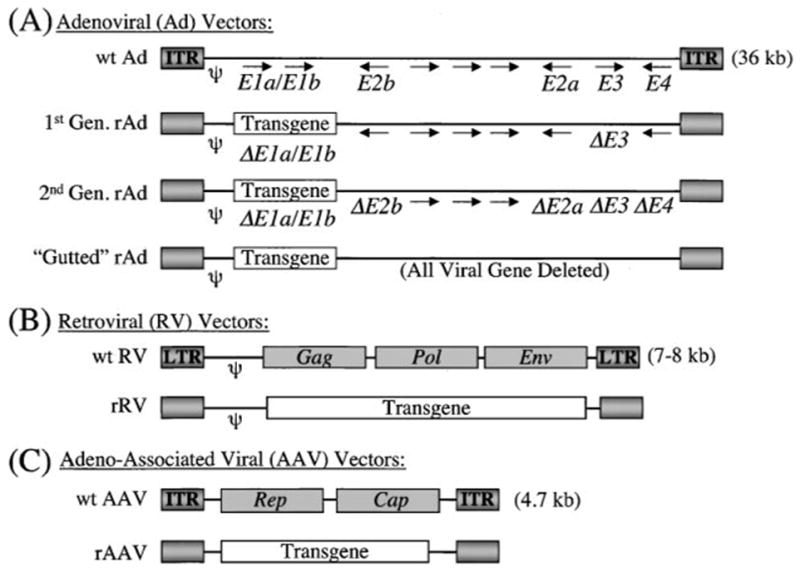

Adenovirus has been one of the most extensively studied recombinant viral systems for gene transfer to the lung (12). Adenovirus has a large, complex linear 36-kb DNA genome and is attractive for gene therapy to the lung because it efficiently transduces non-dividing cells of the airway (13). Because the vector genomes persist as episome and do not integrate, repetitive dosing would be required in any gene therapy protocol for inherited genetic deficiencies. Numerous regulator and structural viral genes have made this virus one of the more complex vector systems to engineer in a fashion that does not invoke a cellular immune response. First-generation vectors (Figure 1) are characterized by E1a/E1b viral gene deletions that inhibit, but do not completely prevent, viral gene expression and replication. Transgene sequences are normally inserted into the E1-deleted region but can also be inserted into the E3 region. In most first-generation vectors, the E3 region has also been deleted to make room for the insertion of a transgene cassette. Animal studies in mice and cotton rats have demonstrated extremely efficient gene transfer to the airway for both CFTR (14, 15) and AAT (8). However, comparison of mouse and human models of the airway have demonstrated that transduction from the apical surface of human airway cells is much less efficient than that found in rodents (16, 17). In part, this difference is thought to be the result of species-specific differences in the abundance of the Coxsackie adenovirus receptors (CAR) (18) on the apical surface of airway cells (19). αVβ5 integrin, an identified co-receptor for adenovirus type-2 (20), is also localized to the basolateral membrane of human airway epithelium and may be responsible for the low efficiency of recombinant adenovirus infection in polarized airway epithelia (21, 22).

Figure 1.

Structural basis for the most commonly used viral vectors for gene therapy. Wild-type viral and recombinant viral genome structure is depicted for (A) adenovirus, (B) retrovirus, and (C ) adeno-associated virus. The wild-type adenoviral genome is depicted with the major viral genes (E1a/E1b, E2a, E2b, E3, and E4) that are manipulated in the three generations of recombinant vectors. In gutted (or helper-dependent) recombinant adenoviral vectors, the only necessary sequences required for packaging of the recombinant viral genomes are the psi (ψ) packaging signal and inverted terminal repeats (ITRs). In contrast to adenovirus, the recombinant retroviral and AAV genomes are considerably less complex. Retroviral genes, including Gag, Pol, and Env, are deleted in recombinant vectors and replaced by a transgene. The only sequences required for packaging of recombinant retroviral genomes are the psi (ψ) packaging signal and the long-terminal repeats (LTRs). Similarly, all viral genes, including Rep and Cap, are deleted in rAAV vectors and replaced by a transgene. The only necessary sequences required for packaging of rAAV vectors are the ITRs at either end of the genome. Relative transgene and viral genome size are not drawn to scale.

Gene expression from first-generation vectors is also accompanied by an intense cellular immune response to virally expressed genes (13). In part, this cellular immune response is thought to be the result of cellular transcription factors capable of substituting for E1 functions. These cellular transcription factors appear to be capable of activating enough viral gene transcription to initiate MHC class I-restricted antigen presentation that, in turn, activates CD4+ and CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, which clear virally infected cells (23). Second-generation vectors, in which additional early viral genes are disabled, have been generated in an attempt to reduce viral gene expression that facilitates cellular immune response (24). In such vectors, deletions or temperature-sensitive mutants of E2a, E2b, and/or E4 have been tested with some success (15, 25, 26). Complex complementing cell lines that express E2a, E2b, and/or E4 are needed to propagate second-generation viruses (27). Some of these gene products require regulated expression because they are toxic to cells, thus making large-scale clinical production of virus challenging. These second-generation vector systems have improved the longevity of transgene expression by reducing cellular immune responses to the vector, but they have not completely solved associated immunologic problems (15, 28). Third-generation adenoviral vector systems, also called gutted or helper-dependent adenoviral vectors, have attempted to delete all viral genes from the recombinant vector (29). These studies have provided promising results in liver-directed gene delivery of animal models (30, 31). One highly applicable example of gutted adenoviral vectors for lung disease includes the delivery of the human AAT gene locus to the liver. This approach produced AAT transgene product in the serum for more than one year in mice (30). Although gutted adenoviral vectors have been evaluated for CFTR gene transfer using CF in vitro airway models (32), there is much less work done evaluating delivery of gutted adenovirus to the lung in vivo. The major hurdles for this vector system are production and generation of replication-competent adenovirus during passaging and propagation. Several strategies using CRE/Lox (33) or FLP/frt (34) helper adenoviral vector systems have aided in increasing the purity of vector preparation. However, adequate production systems are still in need of major advances before this type of vector system will be ready for clinical testing.

Although helper-dependent adenoviral vectors are devoid of all viral genes and, hence, lack cellular immunity to foreign viral antigens, cellular immunity for foreign transgenes remains a concern. Additionally, adenoviral vectors invoke a substantial humoral immune response that inhibits repeat administration to the lung (23). Several strategies to reduce both humoral and cellular responses have been tested in animal models and include the use of immunomodulatory agents or antibodies (35, 36). However, the recent death of a patient undergoing liver-directed gene therapy for OTC deficiency with second-generation adenoviral vectors (37) has suggested that the immunology of adenovirus in humans may be poorly understood. For example, a recent report has described complement activation with adenoviral particles in the presence of pre-existing antibodies (38). Such mechanisms may play a role in the acute toxicity seen in clinical trials, and further investigation into acute innate immune response to viral capsid proteins is needed.

Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus

Over the past decade, the field of molecular medicine has witnessed a growing interest in the development of recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) as a gene delivery vehicle. In part, this renewed interest stems from the shortcomings of recombinant adenovirus-invoked immunity. In contrast to adenovirus, wild-type AAV is not responsible for any known human disease. Even in its wild-type form, AAV is replication defective and requires co-infection with a helper virus, such as adenovirus or herpes virus, for lytic phase productive replication. Most importantly, however, is the simplicity of the 4700 nucleotide single-stranded DNA genome that makes vectoring with this virus much less complex. The wild-type AAV genome consists of two families of genes, Rep (encoding regulatory proteins) and Cap (encoding capsid proteins) (Figure 1). Two inverted terminal repeats (ITRs), 145 bases in length, are the only required information for viral replication and the generation of functional rAAV vectors (39). The most extensively studied serotype of rAAV is type 2. However, five additional serotypes (type 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6) with varying receptor specificities have been described. In addition, at least two additional serotypes, AAV-7 and AAV-8, have been recently identified with altered tissue tropisms (39a). In the absence of a helper virus, wild-type AAV-2 establishes a latent, nonproductive infection with long-term persistence by integrating into the host chromosomal DNA (40). With high frequency, wild-type AAV integrates into a specific locus, AAVS1, on human chromosome 19 (41). In contrast to wild-type AAV, the recombinant virus does not integrate at this specific locus in the absence of exogenous Rep (42).

Several primary attachment receptors and co-receptors have been identified for some of the various serotypes of AAV. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) has been identified as the primary attachment receptor for AAV-2 (43). Cellular binding for AAV-4 and AAV-5 also involves interaction with other cell surface glycans such as O-linked and N-linked sialic acid, respectively (44). Two potential co-receptors, including αVβ5 integrin and human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1), are thought to be critical for AAV-2 entry (45, 46). Despite the identification of these receptors and co-receptors, current studies in the field reveal that infectious entry pathways of AAV in the airway are considerably more complex than previously thought. A significant number of preclinical animal studies have been performed with various serotypes of rAAV delivered to the lung. In rodent animal models, rAAV vectors delivered to the lung have shown promising results (47–50). Such encouraging results have also been confirmed in larger animal models such as rabbit, sheep, and nonhuman primate (51–53). Most of the AAV serotypes have been tested for lung gene transfer. Although subtle differences in the efficiencies are found between various laboratories, the general consensus is that transduction efficiencies to airway epithelia follow this general order rAAV-5 > rAAV-6/rAAV1 > rAAV-2 > rAAV-3 > rAAV-4(47, 48, 50, 54–57). At present, it is not known which serotype(s) is best suited for human lung gene transfer, and the answer to this question will likely require clinical trials directly comparing the efficacy of these serotypes.

An attractive feature of rAAV vectors, which are devoid of all viral genes, is the absence of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses (CTL) to the recombinant virus (58–60). Despite the lack of CTL responses to viral antigens, such responses do occur against encoded foreign transgenes (61). Additionally, humoral responses to capsid proteins remain an obstacle for repeat administration of this vector. Early studies in the rabbit airway have correlated the appearance of neutralizing antibody, with reduced infection following a secondary administration (53, 62). Readministration in mouse lung is possible only if transient immunosuppression (with anti-CD40 ligand antibody or CTLA4-immunoglobulin fusion protein) is applied at the time of the initial rAAV inoculation (63). Alternatively, successful readministration can be achieved by using a different serotype AAV vector (54, 55, 64). In contrast to these results, another study in rabbit lung suggests that high levels of serum-neutralizing antibody to AAV capsid does not block repeated delivery to the lung (65). Nevertheless, initial clinical trials should be aimed at patients lacking AAV-neutralizing antibody to avoid encountering the complexities associated with pre-existing immunity. The use of pseudotyping of AAV genomes with various capsid serotypes (66) may also be useful in avoiding humoral responses associated with repeat administration.

Progress in the development of rAAV as a gene therapy vector has been made possible due to intensive scientific research on the basic biology of AAV. Strategies have been developed to solve several long-standing hurdles in the use of this vector system, including viral production and limited packaging capacity. The identification of AAV-binding receptors and co-receptors has revolutionized rAAV purification from traditional cumbersome ultra-centrifugation, to fast and effective methods of affinity chromatography (67). Knowledge of the molecular mechanisms by which rAAV converts its single-stranded DNA genome into large concatamers has also led to the development of novel techniques (termed cis-activation and trans-splicing) to expand the packaging capacity of this vector system (68–71). This more recent advance is described in more detail in a subsequent section discussing dual-vector approaches for rAAV.

Recombinant Retroviruses and Lentiviruses

Maloney murine leukemia virus (MLV)-based vectors were the first type of recombinant retrovirus used for gene delivery. Recombinant MLV-based genomes are composed of two long terminal repeats (LTR) at either end of the genome, and a packing sequence (ψ) (Figure 1). The transgene cassettes (up to 8 kb) are inserted in place of the three viral genes Gag, Pol, and Env. The application of this vector system for in vivo gene delivery in the lung has been hindered by the inability of this virus to infect nondividing cells of the airway epithelium. Nonetheless, MLV-based vectors have been proposed for application of in utero gene transfer, where epithelial proliferation is high (72). The recent development of lentiviral and pseudotyped lentiviral vectors, which can infect nondividing cells (73), has overcome some of the limitations of MLV-based vectors and has renewed interest for this class of retroviridae for in vivo gene delivery to the lung. Two major types of lentiviral vectors have been tested in airway gene delivery models including those engineered from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (74) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) (75). As with other viral vectors, factors at the airway surface pose barriers to retroviral and lentiviral gene transfer. Recently, however, Jaagsiekte Sheep Retrovirus envelope proteins have been shown to stabilize pseudotyped retrovirus in the presence of lung surfactant (76).

Cationic Liposome/DNA Complexes

Cationic liposomes, as a vehicle for delivery of DNA, have also been extensively studied in animal models of lung gene therapy. Major attractions of liposome mediated gene delivery include (a) an easily scalable gene transfer formulation for clinical trials, (b) no apparent size limitation to the DNA transgene being delivered, and (c) the absence of exogenous protein in the delivered complexes that should reduce immune responses to the vector. Despite these theoretical advantages, progress in developing clinically efficacious protocols has been poor owing to the inherently low efficiency of gene transfer, the transient nature of transgene expression, and immunogenicity to unmethylated CpG dinucleotides in plasmid-derived bacterial DNA (77). The mechanism of gene transfer with cationic liposome/DNA complexes is poorly understood, but several general features appear to be important in the efficacy of gene expression with these reagents including (a) the lipid composition, (b) the complex charge density determined by the liposome/DNA ratio, and (c) the size of the complex. All these factors appear to be important for efficient endocytosis and/or intracellular escape from endosomes, which ultimately affect the efficiency of gene transfer (78, 79).

A major obstacle in the use of liposome/DNA complex-mediated gene transfer has been the apparent low level of endocytosis from the apical membrane of differentiated polarized airway epithelia (80). Despite these limitations, studies in CFTR knockout mice have demonstrated the ability of CFTR-expressing liposome/DNA complexes to correct ion transport abnormalities (81, 82). However, studies in CF human bronchial xenografts have demonstrated that cationic liposome can mediate complementation of mucus sulfation defects in CF epithelia but not ion transport abnormalities (83). Improvements in cationic liposome-mediated gene delivery were made possible by a massive functional screen of cationic lipids for gene transfer to the lungs of mice. In this study, the Genzyme Corporation identified a cationic lipid called GL-67 that was 100 times more effective than previously evaluated common cationic liposomes (78). However, even with the most effective GL-67 lipid formulation, gene transfer was maximal at 2 days post-transfection and quickly diminished thereafter. GL-67 lipid formulation was the basis of the first lung clinical trail using aerosolized cationic lipids in normal volunteers (84) and is discussed in more detail in a subsequent section.

AIRWAY TARGETS FOR GENE THERAPY OF CYSTIC FIBROSIS

Biology of CF Lung Disease Pathogenesis and Relationship to Airway Gene Therapy Targets

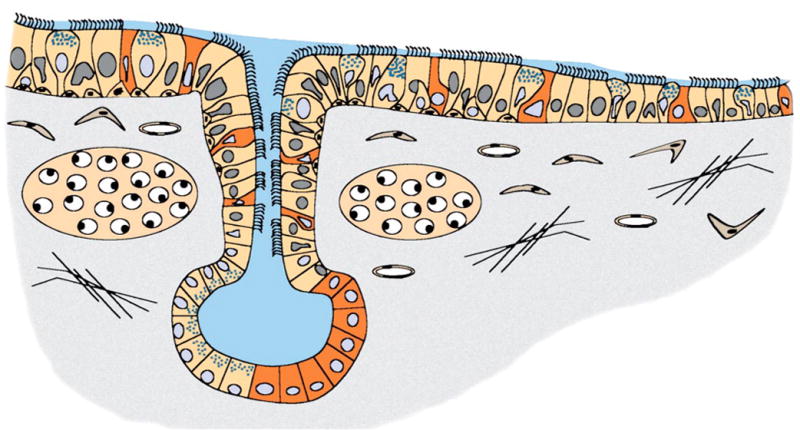

Challenges accompanying gene therapies for CF lung disease are not restricted to the development of efficient and safe vectors for gene delivery but also must reconcile the complexity of cellular sites in the lung that express the CFTR protein and the multiple functions CFTR plays in lung physiology (5). Expression of CFTR is highly regulated in the lung (Figure 2). Ciliated cells appear to express very low levels of functional CFTR (85). In contrast, submucosal glands and a subpopulation of non-ciliated cells with unknown function express extremely high levels of CFTR protein and mRNA (86, 87). In addition to acting as a chloride channel, CFTR has been demonstrated to regulate the activity of other epithelial ion channels such as ENaC and ORCC (5). Defective regulation of ENaC has been proposed to alter fluid transport across CF airways (88), but this notion still remains controversial (89). It is presently unclear whether the highly regulated nature of CFTR expression in various cell types of the airway is an important aspect required for normal lung physiology such as ion and fluid movement across the airway and maintenance of innate lung defense (5). If proper regulation of a CFTR transgene is required to reconstitute normal physiology and innate immunity in the CF lung, then gene therapy approaches will be considerably more complex. The use of the CFTR promoter in gene transfer vectors (90) or in RNA-directed reprogramming (91) may be potential solutions if regulated expression of CFTR is required to restore a normal phenotype to the CF airway.

Figure 2.

Heterogeneity of CFTR-expressing cellular targets for gene therapy of the CF airway. The unique expression patterns of CFTR in the airway pose several hurdles for gene therapy. Nestled beneath the airway are submucosal glands that express abundant CFTR protein in serous cells in the most distal tubules of the glands. CFTR protein is also highly expressed in a non-ciliated cell type in gland ducts and surface airway epithelia. Cell types that express the highest levels of CFTR are shaded in red. Additionally, ciliated cells of the surface airway epithelia also express low levels of CFTR message and protein. Gene therapy strategies for CF must take into account the diversity of cellular targets and levels of CFTR gene expression that may be critical for normal lung physiology.

The finding that CFTR expression is most abundant in submucosal glands of the airway suggests that these regions may also be important gene therapy targets (Figure 2). Submucosal glands also express numerous antibacterial factors such as lysosome and lactoferrin that may be important in protecting the airways from bacterial infection (92). From a gene therapy standpoint, submucosal glands will most definitely be difficult to target from the airway lumen. Several strategies have been proposed to circumvent this potential problem. One such method has utilized the polymeric IgA receptor to target DNA/protein complexes through the blood to glandular cells by transcytosis (93). A second approach proposes to utilize gene targeting to gland stem cells in the surface airway epithelium prior to gland development (72, 94). Such approaches may help to solve the accessibility issues of glandular targets in the adult CF airway.

Level of CFTR Expression Required to Correct CF Disease Phenotypes

Studies evaluating the level of CFTR necessary to sustain normal airway/lung function have used a number of in vivo and in vitro model systems. The most direct measurements have been obtained from the screening of normal individuals with splicing polymorphisms that post-transcriptionally delete part of NBD1 from CFTR pre-mRNA and generate a non-functional transcript (95). These studies demonstrate variation in the splicing of CFTR transcripts within phenotypically normal individuals and suggest that as little as 8% of normal CFTR message is required for normal lung function (95). Furthermore, quantitative RT PCR has demonstrated that CFTR mRNA transcripts are expressed in nasal, tracheal, and bronchial epithelia at approximately one to two copies per cell in normal individuals (96). From a gene therapy standpoint, these results suggest that the level of CFTR correction required for a normal lung phenotype may be quite low. However, when interpreting these data, it is important to appreciate that CFTR is not uniformly expressed in airway epithelia (5). A more relevant approach to determine how much CFTR correction is necessary for normal airway epithelial function came from in vitro CFTR gene transfer studies into CF-polarized epithelia. In contrast to studies correlating phenotypes with the level of endogenous CFTR mRNA, these gene transfer studies have determined the percentage of CFTR overexpressing cells that are required to achieve functional correction of chloride transport abnormalities. Results from these studies suggest that if a CF-polarized airway epithelium overexpresses CFTR in 6% to 10% of the cells, full correction of CFTR-mediated Cl− transport is observed (97). The ability of polarized airway cells to passively equilibrate Cl− through intracellular tight junctions is thought to be the explanation for why overexpression of CFTR in a minority of cells can fully correct Cl− transport defects (97). However, because no current intact animal models of CF lung disease exist, it is presently unclear whether correction of chloride transport abnormalities will equate to correction of bacterial infection in the CF lung.

Studies using recombinant adenovirus and liposome/DNA complex-mediated gene transfer of CFTR in CF airway xenografts have also demonstrated that levels of transgene expression required to complement either electrophysiologic or mucus sulfation defects are significantly different (83). These studies imply that the level of CFTR expression required for normal epithelial function is context-specific for a given primary CF defect. Given the heterogeneity of CFTR expression in various cell types of the lung, this finding is not unexpected. Thus reconstitution of the normal pattern of CFTR protein expression in the airway, even at subnormal levels, may be more efficient at complementing primary defects in CF than treatments generating supra-physiologic expression of CFTR in the wrong cell types. Interestingly, a recent gene therapy technology called spliceosome-mediated RNA trans-splicing (SMaRT) has provided the first evidence that this may indeed be the case. These studies have demonstrated that correction of chloride transport defects in polarized CF epithelia in vitro and human CF bronchial xenografts in vivo is quite efficient (16–22% that seen in non-CF samples) despite what appeared to be a fairly low level of trans-spliced protein (0.2–2% of endogenous) (91) (see below).

Airway Stem Cell Targets for Gene Therapy

The development of gene delivery approaches to target airway stem cells will likely be necessary for sustained therapeutic effects in the lung. Two approaches for gene targeting of airway stem cells can be envisioned. First, gene targeting of airway stem cells in utero poses advantages for correcting those regions of the lung not accessible from the adult airway lumen (i.e., submucosal glands in CF). Second, gene targeting using integrating vectors to adult airway stem cells could substantially improve the longevity of transgene expression in the adult lung. To date, AAV, retroviruses, and lentiviruses hold the most promise because they possess the capacity to integrate into the host genome.

In part, difficulties in identifying and characterizing human airway epithelial progenitor and stem cells have been magnified by differences in lung biology between rodent and human airways. However, human bronchial xenograft models have been useful in studying progenitor-progeny relationships in the human airway (98). In the mouse airway, the predominant cells types include Clara cells and ciliated cells, with a lesser abundance of basal cells in the proximal airways. Until recently, the stem cell of the mouse airway has been thought to be a subset of Clara cells (99). However, more current studies have suggested that the proximal airway of the mouse may also contain a subset of basal-like stem cells that appear to reside in the ducts of submucosal glands in the proximal trachea and neuroepithelial bodies of bronchial airways (100, 101). In contrast to the mouse airway, the predominant airway epithelial cell types in human proximal airways include basal, intermediate, goblet and ciliated cells. However, the more distal airway bronchioles of humans have a cellular composition similar to that of mice with both Clara and ciliated cells as the predominant cell types. Retroviral lineage analysis in adult human bronchial xenografts has identified a diversity of progenitor cells with limited or pluripotent capacity for differentiation into surface airway epithelial phenotypes (94). Interestingly, one of the progenitor cell populations represented by a basal cell-like phenotype has the capacity for pluripotent differentiation into both surface airway epithelial cells and submucosal glands. The recent identification of BrdU label-retaining cells at sites of submucosal gland ducts in the mouse airway (100) suggest that stem/progenitor cell populations in the adult proximal airway may reside in selective niches protected from the external environment. If this is true, then gene targeting of these stem/progenitors may be difficult as they are nestled beneath the airway surface. An alternative strategy to target these populations involves gene delivery in utero before the architecture of the lung is completely developed. Such strategies have, at least in principal, been tested using newborn ferret tracheal xenografts (72). In these studies, retroviral vectors were able to successfully target stem/progenitor cells capable of developing into both surface airway epithelial phenotypes and submucosal glands. Similar approaches have also been tested in sheep using retroviral vectors delivered to the lung (102). However, the feasibility of an in utero lung gene targeting approach for humans is difficult to envision with current state-of-the-art vectors.

BARRIERS TO GENE TRANSFER IN THE LUNG

Physical and Immunologic Barriers to Gene Delivery in the Lung

The airway surface fluid (ASF) and mucous layers are natural barriers in the airway that protect against bacterial and viral infections. Excessive mucus production is also a common pathological change in numerous lung diseases that presents challenges for gene delivery. The intense inflammatory milieu of the CF airway associated with hypersecretion of mucous may also be a significant barrier. Such barriers may affect the efficiency by which recombinant viruses reach their airway targets and/or the immunologic consequences of vector administration. Thick inflammatory sputum from cystic fibrosis (CF) patients has been demonstrated to block and/or inactivate recombinant adenoviral- (103–105), liposome/DNA complex-(103, 105), and AAV-mediated transduction of cells in vitro (106). Although normal human airway surface fluid or sputum does not appear to affect AAV (56, 106) or adenoviral (105) transduction, it does appear to reduce liposome/DNA-mediated gene delivery more than 25-fold (105).

Cellular debris, notably DNA and actin, contributes to the increased viscosity of airway surface fluid in CF lungs (107, 108) and reduces the efficiency of adenovirus transduction in cell cultures (103). Two agents, including recombinant human de-oxyribonuclease (rhDNase) and gelsolin, have been shown to reduce the viscosity of CF sputum by degrading or depolymerizing DNA and actin, respectively. Thus these agents offer potential solutions for circumventing barriers to gene transfer in the CF airway (107). Applications of mucolytic agents, such as rhDNase, have been shown to enhance gene transfer with adenoviral vectors in the presence of CF sputum in vitro (103). The CF airway sputum also contains an elevated level of human defensin proteins (HNP) secreted from abundant neutrophils present in the inflamed CF airway. Purified HNPs and those found in BALs appear to inhibit both recombinant adenoviral and AAV infection of cells in culture (106, 109) but can be reversed upon the addition of AAT (106). In addition to HNPs, the aqueous sol fraction of sputum has adenoviral-specific antibodies in a subset of CF patients that inhibits adenoviral infection in a dose-dependent manner (104). Selection of patient populations for pre-existing antibodies to various serotypes of virus used for gene delivery may be one potential solution to avoid humoral immunity that may decrease the efficacy of viral-mediated gene delivery.

Polarity of Airway Epithelial Gene Transfer and Intracellular Barriers to Viral Transduction

The highly polarized organization of airway epithelia and the complexity of the apical cell surface glycocalyx has created significant barriers for many gene therapy vectors. A general finding for multiple types of recombinant viruses is that polarized airway epithelia are much less susceptible to viral infection from the apical membrane. Preferential transduction from the basolateral membrane of polarized airway epithelia has been observed for recombinant adenoviruses (22, 110), AAV (56), and retroviruses (111). In part, this decreased susceptibility of the apical surface of the airway to infection with adenovirus and AAV have been attributed to the polarity of expressed receptors and co-receptors on the basolateral surface of airway epithelia (19, 21, 22, 56, 110). Additionally, the low rate of endocytosis from the apical plasma membrane of polarized airway epithelia likely accounts for some of the observed polarity of infection with both adenovirus (22) and AAV (56). Several strategies have been developed to enhance recombinant viral-mediated transduction from the apical surface of airway epithelia. First, transient disruption of tight junctions with hypotonic saline and divalent cation chelating agents (such as EGTA) have been used to enhance recombinant adenoviral- (112, 113), AAV- (48, 56), retroviral- (113), and liposome/DNA complex-mediated transduction (114). This method appears to increase the accessibility of apically applied virus to basolateral receptors. Second, receptor-independent pathways of both recombinant adenoviral- and AAV-mediated transduction can be improved with UV irradiation or calcium phosphate co-precipitation (47, 56, 115).

Studies evaluating rAAV transduction biology in the airway suggest that intracellular barriers in polarized airway epithelia also significantly influence the efficiency of transduction from the apical membrane (48). Despite the lack of known cellular-docking proteins on the apical surface of polarized airway epithelia, apical membrane endocytosis of rAAV-2 at high multiplicities of infection is only four- to fivefold less efficient than that from the basolateral side (48, 56). Interestingly, rAAV-2 viral DNA that enters airway epithelia through the apical membrane appears to be quite stable but lacks the ability to convert its single-stranded DNA genome into a transcriptionally active state. In contrast, rAAV-2 viral DNA that enters airway epithelia through the basolateral membrane efficiently converts its single-stranded genome into circular and concatamer genomes and expresses its encoded transgene 200 times more effectively than following apical infection (48). Obviously, additional barriers to apical infection with rAAV-2 must exist in polarized airway epithelia. Such a notion that post-entry barriers exist for rAAV transduction has also been recognized for other non-airway cellular systems (116). One potentially important intracellular barrier for rAAV-mediated delivery to the airway was uncovered when tripeptide proteasome inhibitors were found to significantly enhance rAAV-2 transduction from the apical membrane of polarized airway epithelia without effecting binding or endocytosis (48). In vivo application of such proteasome inhibitors at the time of infection also enhanced rAAV-2 transduction in the mouse lung from undetectable levels to an average of 10% epithelial cells in large bronchioles. Furthermore, involvement of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway appears to be a general feature of both AAV-2- and AAV-5 capsid-mediated transduction (66). The mechanistic involvement of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in rAAV transduction remains somewhat unclear. However, current hypotheses suggest that ubiquitination of both AAV-2 and AAV-5 capsid proteins may be a signal for viral uncoating (66).

NEW TECHNOLOGIES

Dual-Vector Approaches Capable of Expanding rAAV Packaging Capacity

rAAV vectors have become increasingly recognized as a superior choice for gene delivery to the lung. However, a major limitation of this vector system has been the limited packaging capacity of the recombinant vector genome. Studies by Dong and colleagues have demonstrated that packaging of vector genomes, and hence functional titer, drops significantly when the recombinant vector genomes are greater than 5 kb (117). Because ITRs in the recombinant genomes are approximately 300 base pairs, the largest transgene cassette (including promoter, cDNA, and polyA) that can be efficiently delivered by a single rAAV genome is approximately 4.7 kb. From the standpoint of cystic fibrosis, where the minimal size of the CFTR cDNA is approximately 4.5 kb, the gene regulatory element (i.e., promoter and polyA) must be limited to less than 200 base pairs. Potential solutions to this problem have been proposed and include the use of engineered short promoters (118), or the ITR, as a promoter to drive expression of a transgene (119). However, clinical trials, using a rAAV-2 vector (tgAAVCF) that expresses the CFTR cDNA from the ITR promoter, suggest that the low level of expression from the ITR may be a significant hurdle for this approach (120). Alternative approaches have attempted to remove non-essential regions of the CFTR cDNA in an effort to increase the space for a highly active promoter (121). However, given the fact that CFTR functional involvement in the CF lung is poorly understood, such approaches that delete segments of the CFTR cDNA may have unknown consequences on CFTR function in vivo.

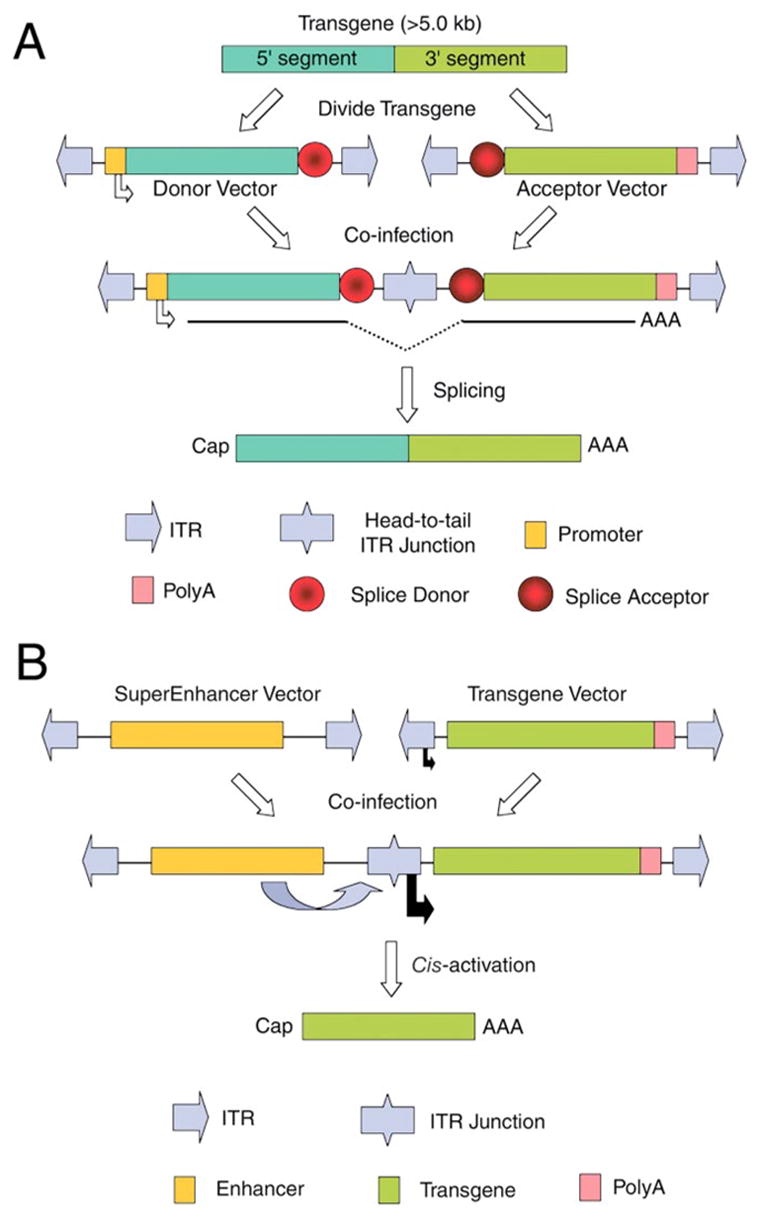

Recent advances evaluating the basic biology of rAAV genome conversion have uncovered a property of this virus’s latent life cycle that has expanded the capacity of this vector system. Important findings in this regard include the discovery that two independent rAAV vector genomes recombine within a cell to form large intermolecular concatamers (122). These groundbreaking studies led to the initial hypothesis that the 5-kb packaging limitation of rAAV vector could be bypassed using an approach based on heterodimerization of two independent vectors. This technology involves dividing a gene expression cassette into two parts, each encoded within separate AAV virions. When co-administered to cells, the linear viral genome in each of the vectors forms heterodimers and concatamers through a mechanism(s) involving intermolecular recombination between linear and/or circular forms of the AAV genomes (122, 123). Subsequent research has applied these findings to the development of two types of dual rAAV vector technologies. The first utilizes trans-splicing vectors for large transgenes exceeding the single-vector packaging limit (69–71, 124). This trans-splicing approach involves the division of a cDNA at potential splice junctions and the incorporation of a heterologous intronic sequence-containing splice donor and acceptor sites flanking the two halves of the transgene cassette (Figure 3A). In this strategy, two vectors (acceptor and donor) can be co-administered and reconstitute the trans-gene product by splicing in trans across the two independent viral genomes that are physically linked by intermolecular recombination. This approach has been tested using the reporter LacZ gene (70, 71, 124), as well as an intact Epo genomic loci (69). The second dual-vector technology, termed cis-activation, incorporates transcriptional enhancers into one rAAV vector and a complete transgene cassette into a second vector (Figure 3B) (68). Following co-administration of the two vectors and intermolecular concatamerization, the transcriptional elements in one vector can activate expression from the second transgene-containing vector. This approach has been shown to be extremely effective in augmenting expression (200–600- fold) from either the ITR promoter or a small heterologous promoter such as SV40. Because the transcriptional promoter elements can be significantly reduced in size, or even omitted from the transgene-containing vector, this approach may be particularly useful for cDNA/polyA cassettes approaching 4.7 kb in length (for example, CFTR).

Figure 3.

Dual-vector heterodimerization approaches expand the packaging capacity of recombinant adeno-associated virus. (A) Trans-splicing heterodimerization approaches utilize two vectors, each encoding two halves of a transgene juxtaposed by flanking donor or acceptor splice sequences. Following co-infection of a cell with both the donor and acceptor vectors, intermolecular recombination reconstitutes an intact functional genome in the head-to-tail orientation capable of trans-splicing an intact transgene transcript across the two covalently linked vector genomes. (B) The cis-activating heterodimerization approach utilizes two vectors for which one encodes transcriptional enhancer sequences, and the other encodes an intact transgene cassette. Following co-infection of a cell with both the SuperEnhancer and Transgene vectors, intermolecular recombination leads to enhanced transcription of the transgene from either the ITR (as shown) or a minimal short promoter (not diagrammed). Although only head-to-tail heterodimers are shown, this approach is independent of the orientation of concatamerization.

Self-Complementing rAAV Vectors

As discussed above, intracellular barriers for AAV transduction have limited the application of this vector type for certain tissues. One additional barrier that significantly controls the efficiency of rAAV-mediated gene expression is the rate at which the single-stranded AAV genome is converted into transcriptionally active double-stranded DNA genomes. In the lung, and in many other organs such as muscle and liver, transgene expression from rAAV vectors takes months to reach maximal levels (48). Studies evaluating short self-complementing rAAV vectors suggest that post-nuclear events involved in second-strand conversion of vector genomes may be limiting in certain systems (125). Self-complementing rAAV vectors were identified when it was discovered that proviral vector genomes 2.5 kb or smaller in size give rise to viral particles containing plus and minus strand genomes covalently linked at one end. The packaging of these short replication intermediates led to the development of self-complementing rAAV vectors. Because the onset of transgene expression is much reduced with self-complementing rAAV vectors, they are particularly attractive for use in disease settings where immediate transgene expression is required. Hence, they may have a particular advantage for use in gene therapy of acute lung diseases. One of the major limitations of this approach, however, is the reduced size of the transgene cassette (<2.5 kb).

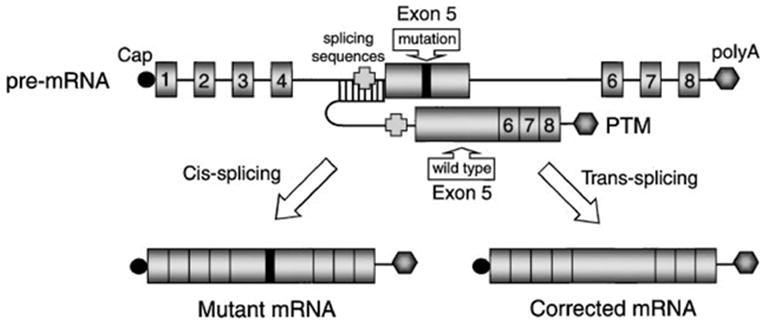

Spliceosome-Mediated RNA Trans-Splicing

The ability to target expression of a transgene at normal endogenous levels and cellular sites may be critical to restoring normal function in certain diseases. As discussed in detail above, this may be particularly important for complex disorders such as CF, where functional complexities of CFTR are superimposed on a diverse and heterogeneous expression profile of the CFTR protein in various airway cell types. A gene targeting technology termed spliceosome-mediated RNA trans-splicing (SMaRT) was recently developed and applied in the context of CF to address shortcoming of traditional gene therapy approaches (126) (Figure 4). At the foundation of this technology are cellular factors involved in processing of pre-mRNA transcripts through an enzymatic reaction that catalyzes the excision of introns and the subsequent joining of adjacent exons to form mRNA. SMaRT technology utilizes a less characterized mechanism for RNA processing that can form functional hybrid mRNAs by intermolecular splicing between different pre-mRNA molecules. Gene therapy vectors used in the SMaRT approach express part of a target cDNA juxtaposed with trans-splicing sequences important in directing the pre-therapeutic mRNA (PTM) to the splicing junctions of the target pre-mRNA (Figure 4). SMaRT technology has been successfully used to correct CFTR ion transport abnormalities in CF airway models (91). A major advantage of this approach is the fact that only those cells expressing the targeted gene pre-mRNA have the capacity to be corrected. Thus potential problems associated with ectopic expression of a transgene can be avoided.

Figure 4.

Spliceosome-mediated RNA trans-splicing (SMaRT) approach. The SMaRT approach for reprogramming mRNA transcripts is useful for gene therapy when gene expression must be regulated, or when a mutant gene product leads to a dominant phenotype. This approach is schematically drawn for a generic gene containing 8 exons and a mutation in exon 5. Following cis-splicing of the mutant pre-mRNA transcript, a mutant gene product is derived. In contrast, trans-splicing between a pre-therapeutic mRNA (PTM) transcript and the endogenous mutant transcript leads to the generation of a full-length functional mRNA. The PTM vector-derived transcript contains a corrected partial cDNA (exons 5–8), preceded by a splicing consensus sequence and an antisense binding domain to the endogenous splice sites in the pre-mRNA mutant target.

Several other notable advantages of SMaRT technology are worth reviewing. First, PTM constructs used in SMaRT are shorter than the full-length cDNA. This is of particular importance for diseases such as CF, where the cDNA and appropriate regulatory elements are too large for incorporation into rAAV vectors. Second, because this approach targets correction to endogenous pre-mRNA, it is particularly useful for disorders where a mutant protein product possesses a dominant, deleterious phenotype. In the case of AAT α–1-antitrypsin deficiency, where processing defects of the z-allele for AAT has been proposed to increase the susceptibility of patients to liver failure (7), SMaRT gene therapy approaches may hold a unique advantage because correction would be associated with a decrease in mutant gene product. Despite the enthusiasm for SMaRT technology, several issues regarding specificity and efficiency still require further investigation.

CLINICAL TRIALS FOR CYSTIC FIBROSIS

Recombinant Adenovirus

The first phase I clinical trial for CF was initiated in 1993 using CFTR expressing recombinant adenovirus delivered to human CF nasal epithelium (127). Partial transient correction of chloride transport defects, as assessed using nasal potential difference (PD) measurements, was observed in this trial and several other nasal trials (127–129). However, subsequent efforts evaluating recombinant adenoviral-mediated delivery of CFTR to the nasal epithelium of CF patients failed to reproduce functional correction (130), leaving investigators to speculate that the delivery method in these previous studies may have damaged the epithelium leading to higher levels of transduction. It has been more difficult to assess functional correction in Phase I studies of adenoviral-mediated delivery of CFTR to the airways of the lung; however, expression analysis suggests that gene transfer is low (<1%) and at higher doses is associated with immunologic responses to the vector (131–133). A recent study by Harvey and colleagues, using repeated localized spray administration of recombinant adenovirus, demonstrated expression of CFTR mRNA at levels theoretically sufficient to correct CFTR chloride transport (~5%) following two administrations. However, a complete loss of expression was seen after a third repeat administration owing to a humoral immune response (134). A more recent phase I clinical trial using aerosolized lobar administration of recombinant CFTR adenovirus demonstrated by in situ hybridization that nuclear-localized vector DNA was not readily detected in small samples of epithelial brushings. However, high levels of infection occurred in mononuclear cells and squamous metaplastic epithelial cells (135). In summary, clinical trials to date with recombinant adenoviral-mediated delivery of CFTR have demonstrated low levels of transduction, likely because the apical surface of airway epithelia lacks CAR receptors.

Cationic Liposome/DNA Complexes

Due to the observed inflammatory responses in initial adenoviral clinical trials, less immunogenic vectors such as liposome/DNA complexes have also been tested as an alternative. In 1995, the first clinical trial using liposomes demonstrated a 20% restoration of transepithelial PD in response to low chloride at 3 days following administration of cationic liposome/DNA complexes to the nasal epithelium (136). Subsequent studies using different compositions of lipids and different promoters to drive CFTR expression demonstrated results comparable to the initial study in CF patients when delivered to the nasal and lung airway epithelium (137–139). Despite the apparent reduced toxicity of liposome/DNA complexes compared with adenovirus trials, a more recent study delivering aerosolized liposome/DNA complexes to the lung, demonstrated that four of eight CF patients developed adverse reactions. Fever, myalgias, and arthralgia, in response to vector administration, were associated with an increase of IL-6 expression (140). These adverse effects are thought to be the result of unmethylated CpG nucleotides in bacterial plasmid DNA. The overwhelming consensus regarding the utility of liposome/DNA complexes in clinical trials for CF is that they may provide some component of low-level correction that is extremely transient.

Adeno-Associated Virus

The most recent vector type tested in clinical trials for CF includes rAAV type-2. The first clinical trail with rAAV-expressing CFTR was performed in the maxillary sinuses in 1998 (141). Results from this study of 10 patients demonstrated a dose-dependent response in the accumulation of vector genomes in sinus epithelium, with little or no immunologic consequences. In a follow-up to this study, a second dose-escalation trial demonstrated partial correction of chloride transport abnormalities by PD measurement in the maxillary sinus with a maximal delivery of 0.1–1 copies of rAAV genomes/cell (142). Expression of the CFTR transgene was detected for as long as 41 to 70 days in 2 of 10 patients. The latest published phase I dose-escalation trial by Aitken and colleagues tested aerosal administration of rAAV-CFTR to the lung (120). Results from this study demonstrated an absence of toxicity with no correlating immune response. At the highest dose (1013 DNA particles/lung), vector genomes were quantified at 0.6 and 1 copies/cell at 14 and 30 days, respectively, and declined to undetectable levels by 90 days post-infection. Disappointingly, no vector-derived mRNA could be detected at any of the time points or vector doses by RT PCR. These findings are reminiscent of in vitro studies in human airway epithelia demonstrating efficient uptake of rAAV-2 and prolonged DNA persistence in the absence of gene expression (48). Furthermore, as outlined earlier in this review, the rAAV vector tested in these clinical trials utilized the ITR as a weak promoter to drive CFTR expression owing to the size constraints of the vector system. This likely also contributed to the undetectable levels of expression in these clinical trials. It is expected that with a better understanding of AAV transduction biology and new AAV serotypes the field can anticipate a very bright future for rAAV-mediated gene therapy of lung disease.

FUTURE PROSPECTS FOR GENE THERAPY TO THE LUNG

The development of many promising technologies has improved the outlook for gene therapy for inherited and acquired diseases of the lung. Many of these advances have stemmed from a comprehensive analysis of vector transduction mechanisms and host cell-vector interactions. Because viral vectors are clearly the most efficient delivery systems at present, aspects regarding the immunology of these vectors in the host will continue to be at the forefront of safety issue concerns. Just as important as the gene delivery vehicle is a concrete understanding of disease pathophysiology and cell biology of the target organ. The identification of relevant pathophysiologic cellular targets and an understanding of target gene function remain critical to developing appropriate strategies for gene therapy and predicting the efficacy of such approaches. Cystic fibrosis is one excellent example where an interplay of gene therapy and cell biology research has enhanced the field’s understanding of disease processes with regard to CF and CFTR function. The development of appropriate animals models for human disease is also critical for increased productive development of clinical gene therapy applications. In the case of CF, the lack of an animal models that mirror the pathoprogression of human lung disease will continue to hinder the field of gene therapy for this disorder. CFTR knockout mice, although extremely useful for studying CFTR function in the gut, have been disappointing when addressing aspects of CF lung disease. With the advent of new transgenic technologies based on somatic cell nuclear cloning, the field is now positioned to expand the use of larger animal models for those genetic diseases that cannot be modeled in the mouse. From both a safety and efficacy standpoint, the current most promising gene delivery systems to the lung for inherited genetic diseases are rAAV vectors. New approaches for purifying large quantities of rAAV vectors have also made widespread clinical applications more feasible. Armed with the appropriate animal model for a given disease and efficient vector systems for gene delivery, the field of gene therapy will likely see great advances over the next decade.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DK47967 (J.F.E) and HL58340 (J.F.E). We also gratefully acknowledge the editorial assistance of Jude Gustafson.

Footnotes

The Annual Review of Physiology is online at http://physiol.annualreviews.org

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Lewin AS, Hauswirth WW. Ribozyme gene therapy: applications for molecular medicine. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:221–28. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)01965-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson PD, Augustin LB, Kren BT, Steer CJ. Gene repair and transposon-mediated gene therapy. Stem Cells. 2002;20:105–18. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.20-2-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welsh MJ, Tsui L-C, Boat TF, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D. Cystic fibrosis. In: Scriver CL, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic Basis of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1995. pp. 3799–876. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guggino WB. Cystic fibrosis and the salt controversy. Cell. 1999;96:607–10. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80570-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang Q, Engelhardt JF. Cellular heterogeneity of CFTR expression and function in the lung: implications for gene therapy of cystic fibrosis. Eur J Hum Gen. 1998;6:12–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snouwaert JN, Brigman KK, Latour AM, Malouf NN, Boucher RC, et al. An animal model for cystic fibrosis made by gene targeting. Science. 1992;257:1083–88. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Steenbergen W. Alpha 1-anti-trypsin deficiency: an overview. Acta Clin Belg. 1993;48:171–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenfeld MA, Siegfried W, Yoshimura K, Yoneyama K, Fukayama M, et al. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of a recombinant alpha 1-antitrypsin gene to the lung epithelium in vivo. Science. 1991;252:431–34. doi: 10.1126/science.2017680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canonico AE, Conary JT, Meyrick BO, Brigham KL. Aerosol and intravenous transfection of human alpha 1-antitrypsin gene to lungs of rabbits. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;10:24–29. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.1.8292378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kay MA, Li Q, Liu TJ, Leland F, Toman C, et al. Hepatic gene therapy: persistent expression of human alpha 1-antitrypsin in mice after direct gene delivery in vivo. Hum Gene Ther. 1992;3:641–47. doi: 10.1089/hum.1992.3.6-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song S, Morgan M, Ellis T, Poirier A, Chesnut K, et al. Sustained secretion of human alpha-1-antitrypsin from murine muscle transduced with adeno-associated virus vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14384–88. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham FL, Prevec L. Methods for construction of adenovirus vectors. Mol Biotechnol. 1995;3:207–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02789331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kovesdi I, Brough DE, Bruder JT, Wickham TJ. Adenoviral vectors for gene transfer. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1997;8:583–89. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(97)80033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenfeld MA, Yoshimura K, Trapnell BC, Yoneyama K, Rosenthal ER, et al. In vivo transfer of the human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene to the airway epithelium. Cell. 1992;68:143–55. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90213-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y, Nunes FA, Berencsi K, Gonczol E, Engelhardt JF, Wilson JM. Inactivation of E2a in recombinant adenoviruses improves the prospect for gene therapy in cystic fibrosis. Nat Genet. 1994;7:362–69. doi: 10.1038/ng0794-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grubb BR, Pickles RJ, Ye H, Yankaskas JR, Vick RN, et al. Inefficient gene transfer by adenovirus vector to cystic fibrosis airway epithelia of mice and humans. Nature. 1994;371:802–6. doi: 10.1038/371802a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engelhardt JF, Yang Y, Stratford-Perricaudet LD, Allen ED, Kozarsky K, et al. Direct gene transfer of human CFTR into human bronchial epithelia of xenografts with E1-deleted adenoviruses. Nat Genet. 1993;4:27–34. doi: 10.1038/ng0593-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergelson JM, Cunningham JA, Droguett G, Kurt-Jones EA, Krithivas A, et al. Isolation of a common receptor for Coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science. 1997;275:1320–23. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walters RW, Grunst T, Bergelson JM, Finberg RW, Welsh MJ, Zabner J. Basolateral localization of fiber receptors limits adenovirus infection from the apical surface of airway epithelia. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10219–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greber UF, Willetts M, Webster P, Helenius A. Stepwise dismantling of adenovirus 2 during entry into cells. Cell. 1993;75:477–86. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90382-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldman MJ, Wilson JM. Expression of alpha v beta 5 integrin is necessary for efficient adenovirus-mediated gene transfer in the human airway. J Virol. 1995;69:5951–58. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.5951-5958.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pickles RJ, McCarty D, Matsui H, Hart PJ, Randell SH, Boucher RC. Limited entry of adenovirus vectors into well-differentiated airway epithelium is responsible for inefficient gene transfer. J Virol. 1998;72:6014–23. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6014-6023.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Li Q, Ertl HC, Wilson JM. Cellular and humoral immune responses to viral antigens create barriers to lung-directed gene therapy with recombinant adenoviruses. J Virol. 1995;69:2004–15. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2004-2015.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeh P, Perricaudet M. Advances in adenoviral vectors: from genetic engineering to their biology. FASEB J. 1997;11:615–23. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.8.9240963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engelhardt JF, Litzky L, Wilson JM. Prolonged transgene expression in cotton rat lung with recombinant adenoviruses defective in E2a. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:1217–29. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.10-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lusky M, Christ M, Rittner K, Dieterle A, Dreyer D, et al. In vitro and in vivo biology of recombinant adenovirus vectors with E1, E1/E2A, or E1/E4 deleted. J Virol. 1998;72:2022–32. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2022-2032.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorziglia MI, Lapcevich C, Roy S, Kang Q, Kadan M, et al. Generation of an adenovirus vector lacking E1, e2a, E3, and all of E4 except open reading frame 3. J Virol. 1999;73:6048–55. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6048-6055.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engelhardt JF, Ye X, Doranz B, Wilson JM. Ablation of E2A in recombinant adenoviruses improves transgene persistence and decreases inflammatory response in mouse liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6196–200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou H, Pastore L, Beaud L, et al. Helper-dependent adenoviral vectors. Methods Enzymol. 2002;346:177–98. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)46056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morral N, Parks RJ, Zhou H, Langston C, Schiedner G, et al. High doses of a helper-dependent adenoviral vector yield supraphysiological levels of alpha1-antitrypsin with negligible toxicity. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2709–16. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.18-2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schiedner G, Morral N, Parks RJ, Wu Y, Koopmans SC, et al. Genomic DNA transfer with a high-capacity adenovirus vector results in improved in vivo gene expression and decreased toxicity. Nat Genet. 1998;18:180–83. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher KJ, Choi H, Burda J, Chen SJ, Wilson JM. Recombinant adenovirus deleted of all viral genes for gene therapy of cystic fibrosis. Virology. 1996;217:11–22. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parks RJ, Chen L, Anton M, Sankar U, Rudnicki MA, Graham FL. A helper-dependent adenovirus vector system: removal of helper virus by Cre-mediated excision of the viral packaging signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13565–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng P, Beauchamp C, Evelegh C, Parks R, Graham FL. Development of a FLP/frt system for generating helper-dependent adenoviral vectors. Mol Ther. 2001;3:809–15. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y, Su Q, Grewal IS, Schilz R, Flavell RA, Wilson JM. Transient subversion of CD40 ligand function diminishes immune responses to adenovirus vectors in mouse liver and lung tissues. J Virol. 1996;70:6370–77. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6370-6377.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Y, Trinchieri G, Wilson JM. Recombinant IL-12 prevents formation of blocking IgA antibodies to recombinant adenovirus and allows repeated gene therapy to mouse lung. Nat Med. 1995;1:890–93. doi: 10.1038/nm0995-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raper SE, Yudkoff M, Chirmule N, Gao GP, Nunes F, et al. A pilot study of in vivo liver-directed gene transfer with an adenoviral vector in partial ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:163–75. doi: 10.1089/10430340152712719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cichon G, Boeckh-Herwig S, Schmidt HH, Wehnes E, Muller T, et al. Complement activation by recombinant adenoviruses. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1794–800. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samulski RJ, Chang LS, Shenk T. Helper-free stocks of recombinant adeno-associated viruses: normal integration does not require viral gene expression. J Virol. 1989;63:3822–28. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3822-3828.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39a.Gao GP, Alvira MR, Wang L, Calcedo R, Johnston J, Wilson JM. Novel adeno-associated viruses from rhesus monkeys as vectors for human gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11854–59. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182412299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berns KI. Parvovirus replication. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:316–29. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.3.316-329.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kotin RM, Siniscalco M, Samulski RJ, Zhu XD, Hunter L, et al. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2211–15. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kearns WG, Afione SA, Fulmer SB, Pang MC, Erikson D, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV-CFTR) vectors do not integrate in a site-specific fashion in an immortalized epithelial cell line. Gene Ther. 1996;3:748–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Summerford C, Samulski RJ. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J Virol. 1998;72:1438–45. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1438-1445.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaludov N, Brown KE, Walters RW, Zabner J, Chiorini JA. Adeno-associated virus serotype 4 (aav4) and aav5 both require sialic acid binding for hemagglutination and efficient transduction but differ in sialic acid linkage specificity. J Virol. 2001;75:6884–93. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.6884-6893.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Summerford C, Bartlett JS, Samulski RJ. Alphavbeta5 integrin: a co-receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. Nat Med. 1999;5:78–82. doi: 10.1038/4768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qing K, Mah C, Hansen J, Zhou S, Dwarki V, Srivastava A. Human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is a co-receptor for infection by adeno-associated virus 2. Nat Med. 1999;5:71–77. doi: 10.1038/4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walters RW, Duan D, Engelhardt JF, Welsh MJ. Incorporation of adeno-associated virus in a calcium phosphate coprecipitate improves gene transfer to airway epithelia in vitro and in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74:535–40. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.535-540.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duan D, Yue Y, Yan Z, Yang J, Engelhardt JF. Endosomal processing limits gene transfer to polarized airway epithelia by adeno-associated virus. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1573–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI8317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weiss DJ, Bonneau L, Allen JM, Miller AD, Halbert CL. Perfluorochemical liquid enhances adeno-associated virus-mediated transgene expression in lungs. Mol Ther. 2000;2:624–30. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Auricchio A, O’Connor E, Weiner D, Gao G, Hildinger M, et al. Non-invasive gene transfer to lung for systemic delivery of therapeutic proteins. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:499–504. doi: 10.1172/JCI15780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Conrad CK, Allen SS, Afione SA, Reynolds TC, Beck SE, et al. Safety of single-dose administration of an adeno-associated virus (AAV)-CFTR vector in the primate lung. Gene Ther. 1996;3:658–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rubenstein RC, McVeigh U, Flotte TR, Guggino WB, Zeitlin PL. CFTR gene transduction in neonatal rabbits using an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector. Gene Ther. 1997;4:384–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halbert CL, Standaert TA, Aitken ML, Alexander IE, Russell DW, Miller AD. Transduction by adeno-associated virus vectors in the rabbit airway: efficiency, persistence, and readministration. J Virol. 1997;71:5932–41. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5932-5941.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Halbert CL, Rutledge EA, Allen JM, Russell DW, Miller AD. Repeat transduction in the mouse lung by using adeno-associated virus vectors with different serotypes. J Virol. 2000;74:1524–32. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.3.1524-1532.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Halbert CL, Allen JM, Miller AD. Adeno-associated virus type 6 (aav6) vectors mediate efficient transduction of airway epithelial cells in mouse lungs compared to that of aav2 vectors. J Virol. 2001;75:6615–24. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6615-6624.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duan D, Yue Y, Yan Z, McCray PB, Engelhardt JF. Polarity influences the efficiency of recombinant adeno-associated virus infection in differentiated airway epithelia. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2761–76. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.18-2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zabner J, Seiler M, Walters R, Kotin RM, Fulgeras W, et al. Adeno-associated virus type 5 (AAV5) but not AAV2 binds to the apical surfaces of airway epithelia and facilitates gene transfer. J Virol. 2000;74:3852–58. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3852-3858.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hernandez YJ, Wang J, Kearns WG, Loiler S, Poirier A, Flotte TR. Latent adeno-associated virus infection elicits humoral but not cell-mediated immune responses in a nonhuman primate model. J Virol. 1999;73:8549–58. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8549-8558.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Somia N, Verma IM. Gene therapy: trials and tribulations. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:91–99. doi: 10.1038/35038533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kay MA, Glorioso JC, Naldini L. Viral vectors for gene therapy: the art of turning infectious agents into vehicles of therapeutics. Nat Med. 2001;7:33–40. doi: 10.1038/83324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang Y, Chirmule N, Gao G, Wilson J. CD40 ligand-dependent activation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by adeno-associated virus vectors in vivo: role of immature dendritic cells. J Virol. 2000;74:8003–10. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.8003-8010.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chirmule N, Xiao W, Truneh A, Schnell MA, Hughes JV, et al. Humoral immunity to adeno-associated virus type 2 vectors following administration to murine and nonhuman primate muscle. J Virol. 2000;74:2420–25. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2420-2425.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Halbert CL, Standaert TA, Wilson CB, Miller AD. Successful readministration of adeno-associated virus vectors to the mouse lung requires transient immunosuppression during the initial exposure. J Virol. 1998;72:9795–805. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9795-9805.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rutledge EA, Halbert CL, Russell DW. Infectious clones and vectors derived from adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes other than AAV type 2. J Virol. 1998;72:309–19. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.309-319.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beck SE, Jones LA, Chesnut K, Walsh SM, Reynolds TC, et al. Repeated delivery of adeno-associated virus vectors to the rabbit airway. J Virol. 1999;73:9446–55. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9446-9455.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yan Z, Zak R, Luxton GW, Ritchie TC, Bantel-Schaal U, Engelhardt JF. Ubiquitination of both adeno-associated virus type 2 and 5 capsid proteins affects the transduction efficiency of recombinant vectors. J Virol. 2002;76:2043–53. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2043-2053.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Summerford C, Samulski RJ. Viral receptors and vector purification: new approaches for generating clinical-grade reagents. Nat Med. 1999;5:587–88. doi: 10.1038/8470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Duan D, Yue Y, Yan Z, Engelhardt JF. A new dual-vector approach to enhance recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated gene expression through intermolecular cis activation. Nat Med. 2000;6:595–98. doi: 10.1038/75080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yan Z, Zhang Y, Duan D, Engelhardt JF. From the cover: trans-splicing vectors expand the utility of adeno-associated virus for gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6716–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun L, Li J, Xiao X. Overcoming adeno-associated virus vector size limitation through viral DNA heterodimerization. Nat Med. 2000;6:599–602. doi: 10.1038/75087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nakai H, Storm TA, Kay MA. Increasing the size of rAAV-mediated expression cassettes in vivo by intermolecular joining of two complementary vectors. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:527–32. doi: 10.1038/75390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duan D, Sehgal A, Yao J, Engelhardt JF. Lef1 transcription factor expression defines airway progenitor cell targets for in utero gene therapy of submucosal gland in cystic tibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;18:750–58. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.6.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Naldini LBU, Gallay P, Ory D, Mulligan R, Gage FH, et al. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science. 1996;272:263–67. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goldman MJ, Lee PS, Yang JS, Wilson JM. Lentiviral vectors for gene therapy of cystic fibrosis. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:2261–68. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.18-2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]