Abstract

Fluorous tagging strategy is applied to solution-phase parallel synthesis of a library containing hydantoin and thiohydantoin analogs. Two perfluoroalkyl (Rf)-tagged α-amino esters each react with 6 aromatic aldehydes under reductive amination conditions. Twelve amino esters then each react with 10 isocyanates and isothiocyanates in parallel. The resulting 120 ureas and thioureas undergo spontaneous cyclization to form the corresponding hydantoins and thiohydantoins. The intermediate and final product purifications are performed with solid-phase extraction (SPE) over FluoroFlash™ cartridges, no chromatography is required. Using standard instruments and straightforward SPE technique, one chemist accomplished the 120-member library synthesis in less than 5 working days, including starting material synthesis and product analysis.

Keywords: hydantoin, thiohydantoin, fluorous synthesis, parallel synthesis, solid phase extraction

1. Introduction

Solution-phase parallel synthesis has become an increasingly important method in medicinal chemistry. Many reaction and purification techniques and instruments, such as parallel reaction vessels, polymer-supported reagents and scavengers, solid phase extractions, and microwave reactions, have been employed in parallel synthesis. The conventional solution-phase parallel synthesis requires minimum method development effort. However, purification is an obstacle because chromatography is usually needed for each reaction mixture. On the other hand, polymer supported solution-phase synthesis simplifies the purification, but it has restrictions due to the heterogeneous reaction conditions which usually slow the reaction. Fluorous synthesis is a complementary type of liquid-phase synthesis that has the character of solution-phase reactivity and solid-phase type separation [1–4]. Fluorous synthesis employs perfluoroalkyl chains (Rf) as the phase-tag for easy separation. Since the light fluorous molecules have good solubility in common organic solvents, fluorous reactions can be conducted in a homogeneous environment with favorable reaction kinetics. The scope of fluorous reactions is similar to conventional solution-phase synthesis. The separation of reaction mixtures containing light fluorous molecules can be achieved by fluorous silica gel-based solid-phase extraction (SPE) or HPLC [5–7]. The capability of monitoring the reaction process and analysis of fluorous molecules by TLC, HPLC, MS and NMR is an additional advantage of fluorous synthesis. Since the early development by the Curran group in the late 1990’s, light fluorous synthesis has quickly become an active research area. The fluorous tagging strategy has been introduced to make reagents [8–11], scavengers [12–16], protecting groups [17–21] and related tags [22–23] for parallel and mixture syntheses [24–28]. It has also been used in peptide and oligosaccharide syntheses [29–31].

Hydantoin is an important heterocyclic core that exists in many natural products such as hydantocidin and aplysinopsins (Scheme 1). Hydantocidin is produced from Streptomyces hygroscopicus, which has potent herbicidal activity [32–34]. Aplysinopsins are isolated from marine organisms, and they exhibit cytotoxicity to cancer cells and ability to affect neurotransmitters [35–37]. Other hydantoin derivatives also exhibit a broad range of biological activities in medicinal (antitumor, anticovulsant, antimuscarinic, antiulcer, and antiarrythmic) [38–42] and agrochemical (herbicidal and fungicidal) [43–49] applications. In addition to solution phase synthesis [50–51], solid-phase synthesis of hydantoin has also been reported in the literature [52–56]. A common strategy in solid-phase synthesis is cyclization-assisted cleavage which combines the linker cleavage and ring formation in a single reaction step [57]. One of the first examples of cyclative cleavage of polymer support in solid-phase synthesis was developed in the preparation of hydantoins [58].

Scheme 1.

Hydantoin related natural products

We recently reported a quick synthetic method for hydantoins and thiohydantoins by combination of fluorous tagging strategy with fluorous SPE technique [59–60]. Described in this paper is an application of this method in the parallel synthesis of a 120-member library of hydantoins and thiohydatoins.

2. Results and Discussion

Preparation of the 120-member hydantoin/thiohydantoin library was conducted following the synthetic route illustrated in Scheme 2. Fluorous amino esters 1 were subjected to reductive amination reactions with aldehydes. Intermediates 2 were then reacted with isocyanates or isothiocyanates to form corresponding ureas or thioureas 3 which then underwent spontaneous cyclization to displace the fluorous tags to yield the hydantoin or thiohydantoin rings. The product scaffold has three points of diversity. The scope for R1, R2 and R3 was explored. We found R1 has no significant effect in the parallel synthesis. However, R2 and R3 have to be aromatic groups; otherwise the reductive amination reactions are not clean and the isocyanates/isothiocyanates reactions and sequential cyclizations to form hydantoins/thiohydantoins are slow under our conditions. Two fluorous amino esters with different R1, 6 aromatic aldehydes (R2), and 10 isocyanates or isothiocyanates (R3) were selected as building blocks. Their structures are listed in Scheme 3.

Scheme 2.

Fluorous synthesis of hadontoin analogs

Scheme 3.

Building blocks for parallel synthesis.

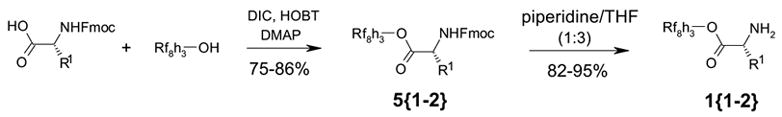

The fluorous tagged amino esters were readily prepared by reacting Fmoc-protected amino acids with a fluorous alcohol containing a C8F17 (Rf8) chain under standard conditions using DIC and HOBT as coupling agents (Scheme 4). The perfluoroalkyl moiety is separated from the hydroxyl group by a propylene spacer to minimize the electronic effect of the fluorous tag. Deprotection of the Fmoc group with 1:3 piperidine/THF provided fluorous amino esters 1. Both reaction steps were carried out under conventional solution-phase conditions. Compounds 5 and 1 can be purified by F-SPE or flash column chromatography with normal silica gel. Fluorous amino esters 1 can also be prepared using Boc-protected amino acids as starting materials.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of fluorous amino esters 1.

Reductive amination reactions were performed in scintillation vials at room temperature followed by a quick aqueous workup. Intermediates 2 were purified by SPE over FluoroFlash™ cartridges. The non-fluorous byproducts and unreacted aldehydes were collected in the first fraction of 80:20 MeOH/H2O, while fluorous products were collected in the second fraction of 100% MeOH. To achieve the best SPE separation, fluorous amino esters 1 were used as the limiting agents so that amines 2 were the only fluorous compounds in the reaction mixtures. In several cases, a small amount of di-N-alkylation compounds were observed as byproducts due to the presence of excess aldehydes and they were collected in 100% MeOH fraction along with the desired mono-N-alkylation products. At the next step of the isocyanate reaction, the byproducts remain unchanged since they cannot be converted to urea 3 and undergo cyclization to form the hydantoins. The di-N-alkylated compounds were retained on the fluorous silica gel during the first F-SPE eluted with 80:20 MeOH/H2O and thus separated from the final products.

At the isocyanate/isothiocyanate addition step, twelve intermediates 2 were split to 10 portions and underwent 120 parallel reactions. The urea/thiourea formation and sequential cyclization were fast and the reaction mixtures were directly loaded on FluoroFlash™ cartridges for SPE without workup. The non-fluorous final products were collected in the first fraction of 80:20 MeOH/H2O, while the cleaved fluorous species, unreacted fluorous amines 2, di-N-alkylation byproducts and ureas 3 (if any) were retained by the fluorous silica gel. Isocyanate/isothiocyanates were used as limiting agents so that products 4 and Et3N were the only non-fluorous compounds collected in the 80:20 MeOH/H2O fraction during SPE purification. Et3N that co-eluted with the products was removed under vacuum during concentration. Typical 1H NMR spectra of one of the final products before and after F-SPE are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

1H NMR (CDCl3) spectra of product 4{2,2,8} before and after F-SPE.

The amount of the final products was targeted at a 30 mg scale. LC-MS analysis revealed that 88% of the 120 products had purities >90% and 90% of the products had overall yields (last step) >50%. Structures, yields, and purities of 15 representative final products are listed in Scheme 5. Products 4{2,5,2} and 4{2,6,2} are axially chiral molecules because the methyl group at the ortho position restricted the free rotation of the C-N bond. They were detected as diastereomeric mixtures by 1H NMR at room temperature.

Scheme 5.

Structures, yields, and puritiesa of 15 representative final products 4{R1,R2,R3}.

In summary, we have demonstrated the utility of the fluorous parallel synthesis in the preparation of a library containing 120 hydantoin and thiohydantoin analogs. The purification was performed by parallel F-SPE. Neither fluorous solvent nor chromatography was needed for the separation of reaction mixtures.

3. Experimental

Fluorous alcohol C8F17CH2CH2CH2OH was available from FTI [61]. Building blocks and reagents were obtained from commercial sources. SPE purification was conducted on a 2x12 SPE manifold available from Supelco and Fisher. NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker AC-270 spectrometer (270 MHz). CDCl3 was used as the solvent unless specifically mentioned. LC-MS spectra were obtained on an Agilent 1100 system.

General SPE procedures

A mixture containing fluorous and non-fluorous compounds in a minimum amount of solvent (< 20% of cartridge volume) is loaded onto a FluoroFlash™ cartridge [61] preconditioned with 80:20 MeOH/H2O. The cartridge is eluted with 80:20 MeOH/H2O (2–5 cartridge volume) for the non-fluorous compound(s) followed by same amount of MeOH for the fluorous compound(s). The loading of a SPE cartridge is around 5–10%. The cartridge can be reused by washing thoroughly with acetone or THF.

Preparation of amino ester 1{1}

A solution of N-Fmoc-L-Leucine (5.30 g, 15 mmol, 1.5 equiv), perfluorooctylpropyl alcohol (4.78 g, 10 mmol, 1.0 equiv), DIC (2.34 mL, 15 mmol, 1.5 equiv), HOBT (2.03 g, 15 mmol, 1.5 equiv) and DMPA (0.12 g, 1.0 mmol, 0.1 equiv) in DMF (20 mL) were stirred overnight at room temperature. The reaction mixture was poured into ice (150 mL) and stirred for 5 min. The solution was decanted and the residue was washed with water one more time. To the residue was then added 20:80 EtOAc/hexane and stirred for 5 min. The white solid was filtered and washed with 20:80 EtOAc/hexane and the filtrate was concentrated. The residue was loaded onto a plug of silica gel (600 g) and eluted with EtOAc/hexane (20:80, 500 mL, 30:80, 1000 mL). The fluorous amino ester 5{1} was obtained as a white solid (7.35 g, 90%) after concentration. 1H NMR δ (ppm): 0.78–1.18 (m, 6H), 1.38–1.85 (m, 3H), 1.88–2.32 (m, 4H), 4.03–4.31 (m, 3H), 4.31–4.58 (m, 3H), 5.12–5.23 (m, 1H), 7.18–7.46 (m, 4H), 7.46–7.68 (m, 2H), 7.68–7.88 (m, 2H); MS (APCI): 814 (M+1)+.

A solution of 5{1} (7.3 g, 9.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in 1:3 pyridine/THF (20 mL) was stirred for 30 min and concentrated. The residue was subjected to column chromatography on silica gel (eluted with 50:50 EtOAc/Hexane, 5:95 MeOH/EtOAc, 10:90 MeOH/EtOAc) to give 1{1} (4.32 g, 90%) as light yellow oil. 1H NMR (δ): 0.93 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 3H), 0.96 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 3H), 1.38–1.68 (m, 4H), 1.68–1.84 (m, 1H), 1.92–2.08 (m, 2H), 2.08–2.32 (m, 2H), 3.50 (dd, J = 6.4, 9.4 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H); MS (APCI): 592 (M+1)+.

Preparation of amino ester 1{2}

A solution of N-Boc-L-Phenylalanine (3.98 g, 15 mmol, 1.5 equiv), perfluorooctylpropyl alcohol (4.78 g, 10 mmol, 1.0 equiv), DIC (2.34 mL, 15 mmol, 1.5 equiv), HOBT (2.03 g, 15 mmol, 1.5 equiv) and DMPA (0.12 g, 1.0 mmol, 0.1 equiv) in DMF (20 mL) were stirred overnight at room temperature. The reaction mixture was poured into ice (150 mL) and stirred for 5 min. The solution was decanted and the residue was washed with water one more time. The residue was then added 20:80 EtOAc/hexane and stirred for 5 min. The white solid was filtered and washed with 20:80 EtOAc/hexane and the filtrate was concentrated. The residue was loaded onto a plug of silica gel (600 g) and eluted with EtOAc/hexane (20:80, 500 mL, 30:80, 1000 mL). The fluorous amino ester 5{2} was obtained as a white solid (6.95 g, 95%) after concentration. 1H NMR δ (ppm): 1.43 (s, 9H), 1.81–2.15 (m, 4H), 2.97–3.08 (m, 2H), 4.03–4.28 (m, 2H), 4.57 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.98 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 7.13–7.21 (m, 2H), 7.25–7.41 (m, 3H); MS (APCI): 726 (M+1)+.

A solution of 5{2} (3.75 g, 5.17 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in 1:4 TFA/DCM (25 mL) was stirred for 2 hours and then concentrated. The residue was dissolved in DCM, basified with NaHCO3 solution, washed with brine, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated to give 1{2} (3.80 g, 100%) as light yellow oil. 1H NMR δ (ppm): 1.55–1.82 (br, 2H), 1.82–2.24 (m, 4H), 2.95 (dd, J = 15 Hz, 7.1 Hz, 1H), 3.07 (dd, J = 15 Hz, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (t, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 4.05–4.23 (m, 2H), 7.15–7.43 (m, 5H); MS (APCI): 626 (M+1)+.

General procedure for reductive amination reactions

To a solution of fluorous amino ester 1 (1.0 equiv) in CH2Cl2 was added the aldehyde (1.1 equiv) in CH2Cl2. After stirring for 5 min, NaBH(OAc)3 (1.2 equiv) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred for 1 hour before quenching with water and NH4OH. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 and the combined organic solution was dried and concentrated. The residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (1.0 mL) and loaded onto a FluoroFlash™ cartridge (10.0 g). The cartridge was eluted with 80:20 MeOH/H2O (2x16 mL) and then MeOH (3x16 mL). The MeOH fractions were combined and concentrated to afford 2 as a white solid.

Analytical data for 2{1,1}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 0.87 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 0.93 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 1.40–1.57 (m, 2H), 1.68–1.87 (m, 2H), 1.90–2.33 (m, 4H), 3.33 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H), 4.21 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 7.23–7.38 (m, 5H); MS (APCI): 682 (M+1)+.

Analytical data for 2{2,1}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 1.70–2.08 (m, 5H), 2.94 (dd, J = 15 Hz, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.08 (dd, J = 15 Hz, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 3.60 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 3.71 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H), 3.86 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H), 3.95–4.18 (m, 2H), 7.13–7.44 (m, 10H); MS (APCI): 716 (M+1)+.

General procedure for the preparation of hydantoins/thiohydantoins 4

To a solution of 2 (1.1 equiv) in CH2Cl2 was added isocyanate or isothiocyanate (1.0 equiv) and Et3N (1.0 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 hour at room temperature and loaded directly onto a FluoroFlash™ cartridge (2 g). The cartridge was eluted with 80:20 MeOH/H2O (2x6 mL) and then acetone (2x6 mL). The 80:20 MeOH/H2O fractions were combined and concentrated to give 4 as a white solid.

Analytical data for 4{1,1,1}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 0.90 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 0.95 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 1.76–1.87 (m, 2H), 1.87–2.07 (m, 1H), 3.93 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.13 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 5.19 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 7.26–7.58 (m, 10H); MS (APCI): 323 (M+1)+.

Analytical data for 4{1,2,3}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 0.91 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 0.96 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 1.76–1.87 (m, 2H), 1.87–2.07 (m, 1H), 2.37 (s, 3H), 2.42 (s, 3H), 3.91 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.06 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 5.17 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.30 (m, 7H), 7.36 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H); MS (APCI): 351 (M+1)+.

Analytical data for 4{1,3,5}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 0.90 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 0.95 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 1.76–1.87 (m, 2H), 1.87–2.07 (m, 1H), 3.95 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.13 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 5.09 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 7.53 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 7.64 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 2H), 7.74 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 2H); MS (APCI): 469 (M+1)+, 471 (M+3)+.

Analytical data for 4{1,4,7}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 0.89 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 0.95 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 1.76–1.87 (m, 2H), 1.87–2.07 (m, 1H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 3.90 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.04 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 5.12 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (dd, J = 2.7, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H); MS (APCI): 421 (M+1)+, 423 (M+3)+.

Analytical data for 4{1,5,9}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 0.96 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 0.99 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 1.88–2.07 (m, 3H), 2.40 (s, 3H), 4.19 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.49 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 5.76 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 6.36–6.49 (m, 2H), 7.18 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 7.43 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H); MS (APCI): 343 (M+1)+.

Analytical data for 4{1,6,9}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 0.91 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 1.88–2.07 (m, 3H), 2.42 (s, 3H), 3.93 (s, 2H), 4.09 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.43 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 6.04 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 7.18–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.30–7.47 (m, 5H), 7.54–7.63 (m, 2H), 7.77–7.87 (m, 2H); MS (APCI): 441 (M+1)+.

Analytical data for the major diastereomer of 4{2,6,2}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 2.19 (s, 3H), 3.19–3.43 (m, 2H), 3.93 (s, 2H), 4.15–4.35 (m, 2H), 5.39 (d, J = 13.5 Hz, 1H), 7.09–7.49 (m, 13H), 7.54–7.65 (m, 1H), 7.73–7.90 (m, 2H); MS (APCI): 459 (M+1)+.

Analytical data for the major diastereomer of 4{2,5,2}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 2.18 (s, 3H), 3.20–3.33 (m, 2H), 4.18–4.39 (m, 2H), 5.13 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 6.26–6.42 (m, 2H), 7.07–7.41 (m, 9H), 7.41–7.50 (m, 1H); MS (APCI): 361 (M+1)+.

Analytical data for 4{2,4,4}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 2.35 (s, 3H), 3.16–3.33 (m, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 4.03 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 5.18 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 7.13–7.25 (m, 6H), 7.28–7.38 (m, 3H); MS (APCI): 401 (M+1)+.

Analytical data for 4{2,4,6}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 2.47 (s, 3H), 3.16–3.33 (m, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 4.04 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 5.17 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 7.07–7.38 (m, 9H); MS (APCI): 433 (M+1)+.

Analytical data for 4{2,3,6}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 2.47 (s, 3H), 3.16–3.33 (m, 2H), 4.04 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 5.17 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 6.96–7.10 (m, 4H), 7.10–7.21 (m, 2H), 7.10–7.87 (m, 5H), 7.49 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), MS (APCI): 481 (M+1)+, 483 (M+3)+.

Analytical data for 4{2,3,8}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 3.24 (dd, J = 16.2 Hz, 5.3 Hz, 1H), 3.37 (dd, J = 16.2 Hz, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.32 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 4.37 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 5.97 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 6.84–6.95 (m, 1H), 7.12–7.26 (m, 4H), 7.20–7.48 (m, 7H), 7.48–7.59 (m, 2H); MS (APCI): 451 (M+1)+, 453 (M+3)+.

Analytical data for 4{2,2,8}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 2.39 (s, 3H), 3.24 (dd, J = 15.9 Hz, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 3.37 (dd, J = 15.9 Hz, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.32 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.38 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.04 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.84–6.92 (m, 1H), 7.17–7.29 (m, 6H), 7.30–7.48 (m, 7H); MS (APCI): 387 (M+1)+.

Analytical data for 4{2,1,10}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 3.16–3.33 (m, 2H), 4.12 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 4.19 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 5.24 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 7.02–7.14 (m, 4H), 7.14–7.52 (m, 10H); MS (APCI): 375 (M+1)+.

Analytical data for 4{2,2,10}

1H NMR δ (ppm): 2.38 (s, 3H), 3.16–3.33 (m, 2H), 4.08 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 5.21 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 7.00–7.11 (m, 4H), 7.11–7.25 (m, 6H), 7.25–7.40 (m, 3H); MS (APCI): 389 (M+1)+.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences for the SBIR funding (1R43GM066415-01).

Abbreviations

- Rf

perfluoroalkyl group

- SPE

solid-phase extraction

- DIC

1,3-diisopropylcarbodiimide

- HOBT

1-hydroxybenzotriazole

- Fmoc

9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl

- Boc

t-butoxycarbonyl

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- DMAP

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- TLC

thin-layer chromatography

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- FTI

Fluorous Technologies, Inc

Notes and References

- 1.Zhang W. Fluorous technologies for solution-phase high-throughput organic synthesis. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:4475–4489. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gladysz JA, Curran DP. Fluorous chemistry: from biphasic catalysis to a parallel chemical universe and beyond. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:3823–3825. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curran DP. In: Stimulating Concepts in Chemistry. Stoddard F, Reinhoudt D, Shibasaki M, editors. Wiley-VCH; New York: 2000. pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curran DP. Strategy-Level separations in organic synthesis: from planning to practice. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 1998;37:1175–1196. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980518)37:9<1174::AID-ANIE1174>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curran DP. In: The handbook of fluorous chemistry. Gladysz JA, Hovath I, Curran DP, editors. Wiley-VCH; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curran DP. Fluorous reverse phase silica gel. a new tool for preparative separations in synthetic organic and organofluorine chemistry. Synlett. 2001:1488–1496. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curran DP, Oderaotoshi Y. Thiol additions to acrylates by fluorous mixture synthesis: Relative control of elution order in demixing by the fluorous tag and the thiol substituent. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:5243–5253. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dandapani S, Curran DP. Fluorous Mitsunobu reagents and reactions. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:3855–3864. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dobbs AP, McGregor-Johnson C. Synthesis of fluorous azodicarboxylates: towards cleaner Mitsunobu reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:2807–2810. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crich D, Neelamkavil S. The fluorous Swern and Corey-Kim reactions: scope and mechanism. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:3865–3870. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindsley CW, Zhao Z, Newton RC, Leister W, Strauss KA. A general protocol for solution-phase parallel synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:4467–4470. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Werner S, Curran DP. Fluorous dienophiles are powerful diene scavengers in Diels-Alder reactions. Org Lett. 2003;5:3293–3296. doi: 10.1021/ol035214a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Chen CHT, Nagashima T. Fluorous electrophilic scavengers for solution-phase parallel synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:2065–2068. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang W, Curran DP, Chen CHT. Use of fluorous silica gel to separate fluorous thiol quenching derivatives in solution-phase parallel synthesis. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:3871–3875. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindsley CW, Zhao Z, Leister W. Fluorous-tethered quenching reagents for solution phase parallel synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:4225–4228. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindsley CW, Zhou Z, Leister WH, Strauss KA. Fluorous-tethered amine bases for organic and parallel synthesis: scope and limitations. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:3619–3623. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curran DP, Amatore M, Guthrie D, Campbell M, Go E, Luo Z. Synthesis and reactions of fluorous carbobenzyloxy (F-cbz) derivatives of α-amino acids. J Org Chem. 2003;68:4643–4647. doi: 10.1021/jo0344283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Visser PC, van Helden M, Filippov DV, van der Marel G, Drijfhout JW, van Boom JH, Noort D, Overkleet HS. A novel, base-labil fluorous amine protecting group: synthesis and use as a tag in the purification of synthetic peptide. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:9013–9016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Read R, Zhang C. Synthesis of fluorous acetal derivatives of aldehydes and ketones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:7045–7047. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo ZY, Williams J, Read RW, Curran DP. Fluorous Boc (F-Boc) carbamates: new amine protecting groups for use in fluorous synthesis. J Org Chem. 2001;66:4261–4266. doi: 10.1021/jo010111w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rover S, Wipf P. Synthesis and applications of fluorous silyl protecting groups with improved acid stability. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:5667–5670. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang W. Fluorous synthesis of disubstituted pyrimidines. Org Lett. 2003;5:1011–1013. doi: 10.1021/ol027469e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen CHT, Zhang W. FluoMar, A fluorous version of the Marshall resin for solution-phase library synthesis. Org Lett. 2003;5:1015–1017. doi: 10.1021/ol0274864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Q, Lu H, Richard C, Curran DP. Fluorous mixture synthesis of stereoisomer libraries: total syntheses of (+)-murisolin and fifteen diastereoisomers. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:36–37. doi: 10.1021/ja038542e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang W, Luo ZY, Chen CH-T, Curran DP. Solution-phase preparation of a 560-compound library of individually pure mappicine analogs by fluorous mixture synthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10443–10450. doi: 10.1021/ja026947d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Q, Rivkin A, Curran DP. Quasiracemic synthesis: concepts and implementation with a fluorous tagging strategy to make both enantiomers of pyridovericin and mappicine. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:5774–5781. doi: 10.1021/ja025606x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curran DP, Furukawa T. Simultaneous preparation of four truncated discodermolide analogs by fluorous mixture synthesis. Org Lett. 2002;4:2233–2235. doi: 10.1021/ol026084t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo ZY, Zhang QS, Oderaotoshi Y, Curran DP. Fluorous mixture synthesis: a fluorous-tagging strategy for the synthesis and separation of mixtures of organic compounds. Science. 2001;291:1766–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.1057567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazoni L. Rapid synthesis of oligosaccharides using an anomeric fluorous silyl protecting group. Chem Commun. 2003:2930–2931. doi: 10.1039/b311448a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filippov DV, van Zoelen DJ, Oldfield SP, van der Marel GA, Overkleeft HS, Drijfhoutb JW, van Boom JH. Use of benzyloxycarbonyl (z)-based fluorophilic tagging reagents in the purification of synthetic peptides. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:7809–7812. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmacci ER, Hewitt MC, Seeberger PH. ‘Cap-tag’-novel methods for the rapid purification of oligosacchrides prepared by automated solid-phase synthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:4433–4437. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011203)40:23<4433::aid-anie4433>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakajima M, Itoi K, Takamatsu Y, Kinoshita T, Okazaki T, Kawakubo K, Shindo M, Honma T, Tohjigamori M, Haneishi T. Hydantocidin: A new compound with herbicidal activity from Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J Antibiot. 1991;44:293–300. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haruyama H, Takayama T, Kinoshita T, Kondo M, Nakajima M, Haneishi T. Structural elucidation and solution conformation of the novel herbicide hydantocidin. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1991;I:1637–1640. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrington MP, Jung ME. Stereoselective bromination of β-ribofuranosyl amide. Enantioselective synthesis of (+)-hydantocidin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:5145–5148. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hollenbeak KH, Schmitz FJ. Aplysinopsin: Antineoplastic tryptophan derivative from the marine sponge Verongia spengelii. Lloydia. 1977;40:479–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kazlauskas R, Murphy PT, Quinn RJ, Wells RJ. Aplysinopsin, A new tryptophan derivative from a sponge. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977;18:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jakse R, Kroselj V, Recnik S, Sorsak G, Svete J, Stanovnik B, Gradadolnik SG. Stereoselective synthesis of 5-[(Z)-heteroarylmethylidene] substituted hydantoins and thiohydantoins as aplysinopsin. Z Naturforsch. 2002;57B:453–459. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ware E. The chemistry of the hydantoins. Chem Rev. 1950;46:403–470. doi: 10.1021/cr60145a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Struck RF, Kirk MC, Rice LS, Suling WJ. Isolation, synthesis and antitumor evaluation of spirohydantoin aziridine, a mutagenic metabolite of spirohydantoin mustard. J Med Chem. 1986;29:1319–1321. doi: 10.1021/jm00157a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsukura M, Daiku Y, Ueda K, Tanaka S, Igarashi T, Minami N. Synthesis and antiarrhythmic activity of 2,2-dialkyl-1'-(N-substituted aminoalkyl)-spiro-[chroman-4,4'-imidazolidine]-2',5'-diones. Chem Pharm Bull. 1992;40:1823–1827. doi: 10.1248/cpb.40.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brouillete WJ, Jestkov VP, Brown ML, Akhtar MS, DeLorey TM, Brown GB. Bicyclic hydantoins with a bridgehead nitrogen. comparison of anticonvulsant activities with binding to the neuronal voltage-dependent sodium channel. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3289–3293. doi: 10.1021/jm00046a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nefzi A, Giulianotti M, Truong L, Rattan S, Ostresh JM, Houghten RA. Solid-phase synthesis of linear ureas tethered to hydantoins and thiohydantoins. J Com Chem. 2002;4:175–178. doi: 10.1021/cc010064l. references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mizuno T, Kino T, Ito T, Miyata T. Synthesis of aromatic urea herbicides by the selenium-assisted carbonylation using carbon monoxide with sulfur. Synth Commun. 2000;30:1675–1688. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mio S, Ichinose R, Goto K, Sugai S, Sato S. Synthetic studies on (+)-hydantocidin (1): A total synthesis of (+)-hydantocidin, a new herbicidal metabolite from microorganism. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:2111–2120. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mio S, Shiraishi M, Sugai S, Haruyama H, Sato S. Synthetic studies on (+)-hydantocidin (2): Aldol addition approaches toward the stereoisomers of (+)-hydantocidin. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:2121–2132. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mio S, Kumagawa Y, Sugai S. Synthetic studies on (+)-hydantocidin (3): A new synthetic method for construction of the spiro-hydantoin ring at the anomeric position of D-ribofuranose. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:2133–2144. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chemla P. Stereoselective synthesis of (+)-hydantocidin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:7391–7394. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fischer HP, Buser HP, Chemla P, Huxley P, Lutz W, Mirza S, Tombo GMR, van Lommen G, Sipido V. Synthesis and chirality of novel heterocyclic compounds designed for crop protection. Bull Soc Chim Belg. 1994;103:565–581. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sano H, Sugai S. Synthesis of (±)-carbocyclic analogue of spirohydantoin nucleoside. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:4635–4646. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mui M, Ganesan A. Solution-phase synthesis of a combinatorial thiohydantoin library. J Org Chem. 1997;62:3230–3235. doi: 10.1021/jo962376u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sosa ACB, Yakushijin K, Horne DA. Synthesis of axinohydantoins. J Org Chem. 2002;67:4498–4500. doi: 10.1021/jo020063v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lamothe M, Lannuzel M, Perez M. Solid-phase preparation of hydantoins through a new cyclization/cleavage step. J Com Chem. 2002;4:73–78. doi: 10.1021/cc0100520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kita R, Svec F, Frechet JMJ. Hydrophilic polymer supports for solid-phase synthesis: Preparation of poly(ethylene glycol) methacrylate polymer beads using “classical” suspension polymerization in aqueous medium and their application in the solid-phase synthesis of hydantoins. J Com Chem. 2001;3:564–571. doi: 10.1021/cc010020c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Charton J, Delarue S, Vendeville S, Debreu-Fontaine MA, Mizzi S, Sergheraert C. Convenient synthesis of tetrahydroisoquinoline-hydantoins. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:7559–7561. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park KH, Ehrler J, Spoerri H, Kurt MJ. Preparation of a 990-member chemical compound library of hydantoin- and isoxazoline-containing heterocycles using multipin technology. J Com Chem. 2001;3:171–176. doi: 10.1021/cc0000702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dorwald FZ. Organic synthesis on solid phase. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2000. pp. 363–366. references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bräse S, Dahmen S. In: Handbook of Combinatorial Chemistry. Nicolaou KC, Hanko R, Hartwig W, editors. Vol. 1. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2002. pp. 59–169. [Google Scholar]

- 58.DeWitt SH, Kiely JS, Stankovic CJ, Schroeder MC, Cody DMR, Pavia MR. “Diversomers”: an approach to nonpeptide, nonoligomeric chemical diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6909–6913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.6909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang W, Lu Y. Fluorous synthesis of hydantoins and thiohydantoins. Org Lett. 2003;5:2555–2558. doi: 10.1021/ol034854a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang W, Lu Y, Chen CHT. Combination of microwave reactions with fluorous separations in the palladium-catalyzed synthesis of aryl sulfides. Mol Diversity. 2003;7:199–202. doi: 10.1023/b:modi.0000006825.12186.5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.See FTI web page: www.fluorous.com