Abstract

In mice, the relative numbers of male and female pups per litter not only can vary but can probably change over the course of pregnancy in response to numerous environmental and physiological factors. As such, a technique is required to determine gender at several developmental stages. Here we describe a robust and accurate fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) procedure for determining chromosomal sex that can be applied with minimal modification to sperm, pre-and post-implantation conceptuses and recovered dead post-natal pups. Sperm was prepared for FISH analysis y using a modified microwave decondensation–denaturation technique. Preimplantation conceptuses (0.5 dpc) were cultured to the morula stage before sexing. They were then acid-treated to remove the zona pellucida. Tissue homogenates from postimplantational conceptuses (8.5 dpc) and stillborn pups were fixed to pre-etched slides. Specimens were hybridized with identical, commercially available DNA probes for the X (FITC) and Y (Cy3) chromosomes. Sperm ratios met the expected value of 0.5 when determined by using XY FISH. Preimplantation conceptuses pre-treated with pepsin yielded distinct fluorescence of X and Y chromosomes in morulae, whereas microwave decondensation resulted in loss of conceptuses from the slide. Both 4.0 and 8.5 dpc conceptuses displayed mean sex ratios of 0.5. Post-natal FISH analysis allowed gender identification of pups that could not be sexed due to developmental abnormalities or partial cannibalism. FISH analysis of sperm and of multiple conceptuses or post-natal tissue provided a cost-effective, accurate alternative to PCR-based sex determination.

Keywords: Sperm, Embryos, Gender determination, Conceptuses, Offspring

1. Introduction

For several years, this laboratory has been studying mice and ruminant species to determine whether there might be a link between the diet consumed by a mother and the sex of her offspring [[1–3]; Green and Roberts, unpublished work]. A diet high in fat, for example, leads to male-biased litters from mature outbred mice, whereas a diet highly restricted in its fat content has the reverse effect. The mechanisms that cause sex ratio skewing are unclear, although they may operate before or during gamete fusion by a process that allows preferential fertilization by either Y- or X-sperm. Alternatively, there may be selective loss of conceptuses of one sex over the other before or after implantation. Even after birth, phenotypic sexing can be equivocal, as masculinization of the external genitalia, in particular, can be influenced both epigenetically [4–8] and genetically [9,10]. Accordingly, we sought a straightforward direct method that allowed chromosomal sex and sex chromosome numbers to be assessed accurately and economically on populations of sperm, embryos, developing conceptuses and dead, post-natal pups.

Pre-birth gender determination techniques, such as transvaginal sonography [11], ultrasound or computed tomography [12] or PCR gender determination of fetal cells in cervical mucus [13], while successfully applied in humans, have limitations for gender determination in rodents due to the small size of these animals. Moreover, such analyses can be costly for routine use where large numbers of measurements are required and have no value at early developmental stages prior to the emergence of sexually dimorphic landmarks. Detection of DNA sequences specific to X and Y chromosomes through the use of PCR has been employed frequently as a method of gender determination in isolated preimplantation or postimplantational conceptuses [14–16]. This technique is particularly effective for processing large numbers of samples, but the potential exists for erroneous sex identification due to selective amplification of X chromosome genes from maternal uterine tissue that inadvertently occurs in species with highly invasive placentation, such as in rodents and humans [17,18] or where preferential amplification of one allele occurs relative to the other [19].

An alternative approach for sex determination with conceptus or post-natal tissues is identification of sex chromosomes by employing fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) [20] where complementary sequences on interphase X and Y chromosomes are labeled with multi-colored DNA probes (e.g. FITC, Cy3). This procedure allows visual confirmation of not only the presence but the number of X and Y chromosomes. Accordingly, FISH can provide a more complete identification of gender than PCR-based techniques. In addition, error rates may be lower for XY FISH (3–7% range) than for PCR (8–23% range) [19,21], although, we have no data to support such an observation. Overall, PCR and FISH are useful and accurate for gender annotation.

When trying to determine offspring sex, invariably there will be some pups that are aborted and macerated or partially cannibalized, making it impossible to use anogenital distance for gender identification. Additionally, it is not infrequent for mammalian young to be born with ambiguous external genitalia [22,23]. Therefore, FISH could be an alternative to PCR to analyzing the sex chromosome complement, if the methodology could be routinely applied at a low cost. Our objective was to establish a concordant suite of XY FISH-based methods to determine sex chromosome complement of murine sperm and the sex of conceptuses at various stages of murine development.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal breeding

NIH Swiss mice (Mus musculus) were bred and maintained in the University of Missouri’s Animal Science Research Center. All the experiments were carried out according to the NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Missouri’s Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC). Unless otherwise stated, the majority of mice in these studies were fed the Purina 5015 Complete Life Cycle (Purina, St. Louis, MO, USA) control diets. Mice were housed in polysulfone cages (Uni Cage, Siloam Springs, AR, USA; dimensions: 18.4 cm W × 29.2 cm D × 12.7 cm H). During non-breeding periods, four female mice were housed per cage, and during breeding, two females were housed with one male. For those that were permitted to give birth, females were individually housed 1 week prior to breeding.

2.2. Slide preparation and fixation of epididymal sperm

Five male mice (15-week-old) were euthanized by CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation. Epididymal fat pads and associated testes, vas deferens and epididymides were isolated on each side by a transverse incision through the ventrolateral abdominal body wall and inguinal canal. Each epididymis was removed with ethanol-rinsed watchmaker’s forceps and fine scissors [24]. The epididymis was incised at several locations and then placed in 250 μl of sterile phosphate buffered saline (1× PBS) at 30 °C for 10 min to allow sperm transport from the tissue to the culture dish (F. Marchetti, Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, CA, personal communication 2005). Sperm solution was collected separately from each epididymis and stored in a sterile 1.5 ml cryovial.

The sperm solution (5 μl; approximately 60,000 cells/μl) was applied to glass microscope slides pre-soaked in 100% ethanol for 48 h and etched with a diamond scoring pen to indicate the sperm location. Five samples (one per male) were applied per slide as a thin film. Excess sperm was stored in cryovials at − 80 °C. Slides were allowed to air dry flat at room temperature overnight and then dehydrated in 80% methanol at −20 °C for 20 min and again air-dried overnight [25].

2.3. Preimplantation embryos (4.0 dpc)

2.3.1. Breeding and embryo culture

Female mice (20-week-old) were bred to stud males (15-week-old). Conception was assessed by the presence of a coital plug (designated 0.5 dpc). Embryos were surgically collected from oviducts [24]. Cumulus cells were removed by transferring embryos to CZB/H containing 0.3 mg/ml hyaluronidase for 2 min. Embryos were rinsed with fresh CZB/H and then transferred to 25 μl drops of potassium (K(+)) simplex optimized medium (KSOM) under a layer of mineral oil at 37 °C and cultured for up to 4 d in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator.

2.3.2. Slide preparation and fixation

Conceptuses at the late-morula/blastocyst stages were taken out of the KSOM culture, were then washed (three times; 30 s each) in PBS and transferred singly in <2 μl of PBS to pre-etched ethanol-soaked slides. To remove the zona pellucida, each conceptus was immersed in a microdrop (1–2 μl) of 0.01 M HCl/ 0.1% Tween 20 in DEPC-treated water [26]. All procedures were carried out under a dissection microscope (Nikon SMZ-2B, Japan). Slides were then air-dried and stored under nitrogen gas at −20 °C with a desiccant (Drierite; W.A. Hammond Drierite Co. Ltd., Xenia, OH, USA). Up to 35 conceptuses from individual females were applied to a single slide.

2.4. Postimplantational conceptuses (8.5 dpc)

2.4.1. Breeding and conceptus collection

Female mice (20-week-old) were bred to stud males (15-week-old). Conception was assessed by the presence of a coital plug. Pregnant females (n = 8) were housed in separated cages until 8.5 dpc. At 8.5 dpc females were euthanized and conceptuses surgically collected in CZB/H medium at 37 °C from each uterine horn, as described by Conlon [27]. The recovered conceptuses were then transferred to a 60 mm × 15 mm Petri dish containing 1× PBS at 37 °C.

2.4.2. Slide preparation and fixation

Two slide preparation techniques were tested on 11 conceptuses from a single female to achieve optimal cell and chromosomal morphology for hybridization. Individual conceptuses in PBS were sagittally sectioned to separate the cranial and caudal regions. The cranial region was further longitudinally sectioned into two equal halves. The first half of each conceptus was transferred into a DNase/RNase-free PCR tube containing 25 μl of 1× PBS at 37 °C (the second half of the cranial region was used in the slide preparation technique described below). The caudal region was transferred to a PCR tube on ice containing 60 μl 0.1 μg/μl proteinase K (PK) lysis buffer for PCR sex determination (described below). Cranial tissue in 1× PBS was macerated to a single-cell suspension by using a sterile 18 gauge needle and 1 μl was applied to the first etched square of the microscope slide as a thin monolayer of cells. Excess PBS/cell suspension was drawn off the slide. The procedure was repeated for each conceptus, adding cells to subsequent squares and rinsing instruments twice with ethanol between dissections and changing syringe needles between conceptuses. The second slide preparation method was an adaptation of the work of Eicher and Washburn [28]. The cranial region of each conceptus was placed in 50 μl of KaryoMAX colcemid (10 μg/ml in PBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), macerated with a sterile 18 gauge needle and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C to arrest any cells in metaphase. Cells were centrifuged at 400 × g, the supernatant replaced with 100 μl 0.075 M KCl (hypotonic), and the pellet resuspended and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. From this cell suspension, a 1 μl smear was prepared in an etched square of the microscope slide. All cranial region samples (n = 11 from each technique) were prepared on a single slide. Slides were air-dried and stored as described for preimplantation conceptuses.

2.5. Slide preparation and fixation of post-natal tissue

In the course of these experiments, we sought to determine whether this procedure could be applied to dead post-natal pups. However, no set experiment was designed to acquire such tissues. Instead, recovered dead post-natal pups were acquired from another experiment where NIH Swiss female mice were fed either a diet supplemented with omega-3 or omega-6 fatty acids to determine whether these maternal diets altered offspring sex ratio. These studies are still ongoing; definitive results were not available at this time from these experiments. However, we presumed that the diet of the dam would not influence the XY FISH procedure to annotate the gender of the recovered dead pups. Remaining tissue from these individual pups was immediately collected in DNAse/RNAse free microcentrifuge tubes and stored at −20 °C. To prepare slides, approximately 10 mg of frozen tissue (cranial) was dissected and macerated in 50 μl PBS at 37 °C. Slides were prepared and stored as described in Section 2.4.1 for 8.5 dpc conceptuses. A total of 20 pups from dams on the omega-3 (diet 1; n = 13) or omega-6 (diet 2; n = 7) supplemented diets were processed, and as the diet did not influence the FISH procedure, these post-natal results were combined for analysis.

2.6. Fluorescent in situ hybridization

For sperm samples, a modification of the microwave decondensation and codenaturation method of Ko et al. [25] was used for hybridization of the X and Y chromosome probes to the sperm DNA. Briefly, a microwave safe plastic container (21 cm2, 9 cm deep) was filled with 100 ml distilled water. Two slides were placed on a plastic support above the water level in the container. To each slide, dithiothreitol (DTT, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; 200 μl; 10 mM in 0.1 M Tris/HCL buffer, pH 8.0) was added to the dried film of sperm [29], and the sample covered with Parafilm®. Slides were microwaved in the container for 15 s at 550 W. Slides were drained, and the sperm then covered with lithium diiodosalicylate (LIS) (200 μl; 10 mM) and 1 mM DTT in the same 0.1 M Tris/HCl buffer. Parafilm® covers were applied and the slides microwaved in the container for 90 s at 550 W, rinsed twice with 200 μl 2× saline-sodium citrate (2× SSC, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and air-dried. Slides were then treated with 80% methanol at −20 °C for 20 min, air-dried, and used immediately. Two chromosome paints were employed (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL, USA): concentrated mouse X (direct-labeled FITC) and Y (direct-labeled Cy3). Probes were combined in hybridization buffer (Open Biosystems), denatured for 10 min at 65 °C and held at 37 °C for a minimum of 30 min before application to the slides at 37 °C. Coverslips were applied and sealed to the slide with rubber cement. Sperm and probes were denatured simultaneously by microwaving for 78 s at 1100 W. Slides were immediately transferred to a 37 °C pre-warmed humidified chamber for 18 h at 37 °C to complete the hybridization.

Two separate hybridization methods were tested on preimplantation conceptuses (two slides with n = 10 conceptuses each) and optimized to provide consistent fluorescent labeling of X and Y chromosomes. The first method was based on the work of Ko et al. [25] as described above. The second hybridization method was modified based on the work of Coonen [26]. Slides were dehydrated in fresh 80% methanol at −20 °C for 20 min, air-dried 1 h, and then incubated in 100 μg/ml pepsin in 0.01 M HCl at 37 °C for 20 min. After rinsing three times with 500 μl 2× SSC, slides were air-dried for 20 min. Slides were again dehydrated in fresh 80% methanol at −20 °C for 20 min, air-dried, and used immediately for hybridization. Chromosome paints and cover slips were applied as described above. Slides were then denatured for 3 min at 75 °C on a heating block and immediately transferred to a 37 °C pre-warmed humidified chamber and hybridized for 18 h at 37 °C. Postimplantational (8.5 dpc) conceptuses and post-natal tissues were treated by using the modified method of Coonen [26] but with only a 1 min pepsin digestion.

2.7. Post-hybridization treatment

Post-hybridization procedures were modified from the methods of Adler et al. [30], Marchetti et al. [31], and the Open Biosystems wash protocol. All wash solutions in Coplin jars were pre-warmed in a 45 °C water bath for 30 min. Slides were removed from the 37 °C humidified chamber and placed in 1× SSC at 45 °C for 5 min followed by removal of the softened rubber cement from the cover slip with forceps. Slides were immediately placed back in the 1× SSC to release the cover slip. Slides were incubated in the following solutions (two Coplin jars each) at 45 °C for 8 min each: stringency wash solution (50% formamide [Fisher, Fairlawn, NJ, USA]/50% 1× SSC), 1× SSC, and detergent wash solution (Open Biosystems). Slides were drained and attached specimens mounted in reagent containing DAPI (Open Biosystems). Cover slips were applied and sealed with clear nail polish. Slides were either viewed immediately or stored in the dark at 4 °C until earliest possible viewing.

2.8. PCR verification of sex determination

Two PCR protocols were used to verify the XY FISH sex determination in 8.5 dpc conceptuses. Tissues in PK lysis buffer were incubated for 16 h while rotating at 55 °C; 10 μl of this lysate was used in each PCR reaction. The first protocol was a modification of that used by Clapcote and Roder [15; primers Table 1]. Modifications included the addition of 2.5 μl DMSO [Sigma] and 0.25 μl spermidine [Sigma] while maintaining final reactions volume of 25 μl. The PCR reaction was run on an Eppendorf Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY): (1) 94 °C for 5 min, (2) 35 cycles of 94 °C for 20 s, 58 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 40 s, and (3) 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were separated electrophoretically on a 2.5% agarose gel (125 ml, w/v 1× TBE buffer [Sigma]/1.8 μl ethidium bromide [Sigma]). The second PCR protocol of Ramalho et al. [16] used the male-specific sry primers of Zwingman et al. [[32]; Table 1]. The method was optimized by using a gradient thermocycler, resulting in the following PCR conditions: (1) 94 °C for 3 min, (2) 43 cycles of 95 °C for 1 min, 66 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min 10 s, and (3) 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were examined electrophoretically as described above.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for PCR sex determination of murine tissue samples analyzed by XY fluorescent in situ hybridization

2.9. Microscopic and statistical analysis of FISH slides for sex determination

For sperm, 4.0, and 8.5 dpc conceptuses, and post-natal tissue, labeled X and Y chromosomes were scored on an Olympus Provis AX-70 inverted microscope with a U-MBC multi-control box (Melville, NY, USA) equipped with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (Photometrics CoolSnap-ES, Tucson, TX, USA). Images were recorded under DAPI, FITC and Cy3 excitation and emission filters. Fluorophores from each field of view were overlaid to produce a single tri-color image by digital-capture with the MetaMorph Imaging System (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Cells were scored as male or female based on nuclear fluorescence. For sperm samples, a minimum of five fields of view (20× objective/300–500 cells per field of view) per smear were scored and the overall sum of X and Y bearing sperm per sample on each slide was used for statistical analysis. Sex ratio data for sperm, 4.0, and 8.5 dpc, and post-natal samples were analyzed as separate groups by paired t-test (P < 0.05) to determine deviations from expected sex-ratios of 0.5 [33,34].

3. Results

3.1. Epididymal sperm

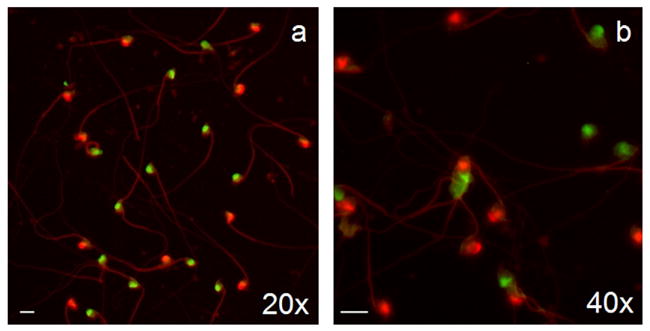

A total of 6048 spermatozoa from five males were scored with the XY FISH technique (Table 2). All five males yielded the expected equal ratio of Y to X chromosomes (paired t-test; P > 0.05). Differences in total sperm number among males are most likely due to variation in masses of epididymal tissue transferred to tubes containing 1× PBS. The simultaneous identification of X and Y chromosomes is illustrated in Fig. 1. Microwave decondensation of spermatozoa resulted in clear hybridization signals for the X and Y chromosomes. The dilution factor for sperm in 1× PBS yielded adequate cell densities with minimal overlap. Some epididymal tissue debris was present on slides, but did not interfere with identification of the sperm, as the probes did not hybridize to these areas.

Table 2.

Sex-ratio of epididymal sperm collected from male NIH Swiss mice (17 weeks) and prepared for FISH by using a modified microwave decondensation–denaturation technique

| Male ID # | Sperm count | Y-sperm | X-sperm | Sex-ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2989 | 1354 | 688 | 666 | 0.51 |

| 2986 | 823 | 420 | 403 | 0.51 |

| 2992 | 1681 | 853 | 828 | 0.51 |

| 2985 | 1278 | 637 | 641 | 0.50 |

| 2802 | 912 | 450 | 462 | 0.49 |

Sperm counts represent totals from a minimum of five fields-of-view (20× magnification) for each individual. None of the samples were different (P > 0.05) from the expected 0.5 ratio of Y chromosomes to total chromosomes.

Fig. 1.

Photomicrographs of multicolor FISH labeling of NIH Swiss mouse sperm (a–b). Samples were hybridized with chromosome-specific painting DNA probes for X (FITC/green) and Y chromosomes (Cy3/red). Sperm samples yielded equal ratios of X and Y chromosome bearing cells. Magnification bar in lower left corner of micrographs represents 10 μm.

3.2. Preimplantation embryos (4.0 dpc)

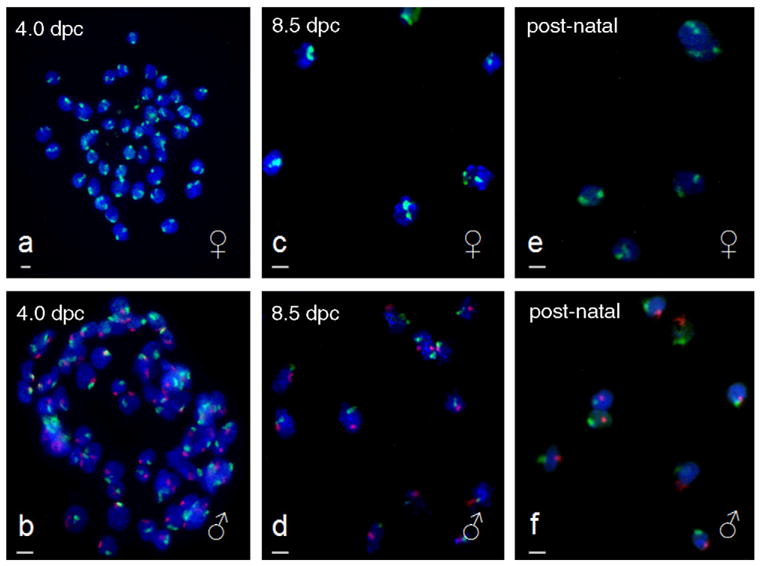

The genotypic gender of a total of 98 conceptuses from nine NIH Swiss females, each with 11.0 ± 1.0 conceptuses (mean ± S.E.M.) was determined with the XY FISH technique (Table 3). Treatment of preimplantation conceptuses with 100 μg/ml pepsin resulted in clear labeling of the X and Y blastomere chromosomes (Fig. 2a–d). Cells were maintained in small clusters and were easily located on the etched grid. The Cy3-labeled (Y) probe fluoresced more intensely than the FITC-labeled (X) probe, but sex determination was not influenced by this slight difference in fluorescence. The sex ratio of conceptuses recovered from individual pregnant females (n = 9) did not differ (mean conceptuses per female ± S.E.M.; males: 5.0 ± 1.0; females 6.0 ± 1.0; P > 0.05). The previously published microwave decondensation technique used for sperm [35] resulted in a loss of conceptuses from slides and could not be used to assess the presence of sex chromosomes.

Table 3.

Frequencies of male and female NIH Swiss preimplantational embryos (4.0 dpc) and postimplantational (8.5 dpc) conceptuses and post-natal tissue as determined by XY chromosomal fluorescent in situ hybridization

| Maternal ID # | Male conceptuses | Female conceptuses | Total conceptuses |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.0 dpc | |||

| 2931 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| 2935 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 2932 | 7 | 7 | 14 |

| 2836 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| 2899 | 7 | 6 | 13 |

| 2835 | 3 | 8 | 11 |

| 2897 | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| 2898 | 9 | 6 | 15 |

| 2839 | 4 | 9 | 13 |

| Total | 45 | 53 | 98 |

| 8.5 dpc | |||

| 2930 | 6 | 5 | 11 |

| 2809 | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| 2819 | 4 | 7 | 11 |

| 2817 | 10 | 2 | 12 |

| 2816 | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| 2840 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| 2843 | 7 | 7 | 14 |

| 2842 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Total | 40 | 36 | 76 |

| Post-natal | |||

| 2777 (n−3) | 1 | 6 | 7 |

| 2703 (n−3) | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| 2718 (n−6) | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Total | 8 | 12 | 20 |

Maternal diets for post-natal samples are indicated next to Maternal ID # (omega-3 supplemented: n−3; omega-6 supplemented: n−6).

Fig. 2.

Photomicrographs of multicolor FISH labeling of NIH Swiss 4.0 dpc preimplantational embryos (a–b), 8.5 dpc postimplantational conceptuses (c–d), and post-natal tissue from stillborn pups (e–f). Samples were hybridized with chromosome-specific painting DNA probes for X (FITC/green) and Y chromosomes (Cy3/red) to determine gender. Male conceptuses (X/Y) are indicated with the symbol ♂ and female conceptuses (X/X) are indicated with the symbol ♀. Magnification bar in lower left corner of micrographs represents 10 μm.

3.3. Postimplantational conceptuses (8.5 dpc)

The presence of XX or XY chromosomes was assessed in 76 postimplantational conceptuses from eight female NIH Swiss females (Table 3). The average number of conceptuses per female was 10.0 ± 1.0 with the same number 5.0 ± 1.0 (P > 0.05) of male and female offspring. The modified method of Coonen [26] provided good cell morphology with reduced cost and time as compared to the Eicher and Washburn [28] modification (Fig. 2e–h), and was subsequently used for all remaining 8.5 dpc conceptuses XY FISH slides from individual pregnant females (n = 7).

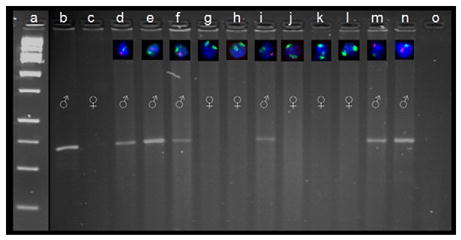

A comparison was made between matched samples analyzed by XY FISH and two separate PCR techniques. Ethidium bromide banding patterns for both sry and Jarid1 PCR methods confirmed the findings of XY FISH analysis. The presence of the male-specific sry amplicon in the 11 conceptus tissue samples and individual cells labeled with X-FITC and Y-Cy3 probes from those same conceptuses are displayed in Fig. 3d–n. Despite the agreement among the techniques, intensity of bands for both sry and Jarid1 amplicons was variable, and thus, gender determination was somewhat equivocal as opposed to the cells analyzed by XY FISH. The striking intensity of the Cy3 staining of the Y chromosome left no doubt as to the gender of the conceptus samples analyzed in this manner.

Fig. 3.

PCR verification of XY FISH technique on for 8.5 dpc conceptuses. Eleven conceptuses from a single female were collected and divided into two portions, one for XY FISH analysis and one for sex determination PCR. Labeled cells via FISH from each conceptus (d–n) are positioned relative to the corresponding PCR sample in their respective ethidium bromide gel lane (male-specific sry PCR; Ramalho et al. [16]). Conceptus cells are labeled with chromosome-specific painting DNA probes for X (FITC/green) and Y (Cy3/red). DNA ladder is present in lane a, known C57 male and female DNA samples are in lanes b and c, and a procedural blank is present in lane o. XY FISH results were also compared to PCR amplification products of the male and female specific Jarid1c and d genes [15] to verify the presence of the X chromosome in female samples (data not shown).

3.4. Post-natal tissue (pups)

Determination of gender based on X and Y chromosomes was possible in post-natal tissue from 20 pups born to three females (Table 3). In six of these dead pups, prior gender determination by anogenital distance was possible (i.e., they were not cannibalized or underdeveloped). The XY FISH procedure provided confirmation of gender by genotype observed in five of six of these pups. The one misdiagnosis was likely due to misinterpretation of the anogenital distance; the XY FISH image revealed strong binding of the Y-probe to the cells from homogenized tissue (Fig. 2). Thus, the XY FISH results were judged to be more credible than the anogenital distance determination, which can provide erroneous results in animals with potentially ambiguous external genitalia.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated a series of optimized methods for XY FISH sex chromosome-determination that can be applied at various stages of mouse development with minimal modification required for each stage. The FISH procedure described herein required microwave decondensation and codenaturation for sperm, and pepsin digestion for embryos, conceptuses, and post-natal tissue. Unequivocal sex chromosome identification was possible in sperm, preimplantation embryos, postimplantational conceptuses, and post-natal pups. The ability to visualize both X and Y chromosomes simultaneously at each stage provides accurate gender annotation and thus greatly reduces the potential for misdiagnosis of genotypic sex. Many previous studies that have employed either PCR or FISH for gender identification have focused on a particular stage of pre-implantation development [19,21,35] or a specific tissue type, e.g. yolk sac tissue [36]. To our knowledge, this work is the first report of FISH sex chromosome determination in successive stages of mouse development, from gamete to parturition, that utilized identical probes and similar techniques across the stages analyzed.

Commercially-supplied chromosomal paints provide a convenient, reliable source of X- and Y-labeling probes, but our initial tests revealed that the supplied protocol was not optimal for the tissues we wanted to examine. Accordingly, we developed tissue-specific optimizations based on previous methods [25,26,37] to yield clear, uniform fluorescence in the samples examined. Sperm required additional decondensation that could not be accomplished with reducing agents and protein solubilizing agents, such as dithiothreitol (DTT) and lithium diiodosalicylate (LIS), alone [30]. By adapting the microwave decondensation method for human sperm cells described by Ko et al. [25] to mouse sperm samples, we observed standardized decondensation of cells and consistent probe hybridization on all regions of the slide. However, this microwave FISH procedure was unsuitable for gender determination of preimplantational conceptuses. Sample loss could have occurred because of the lower ratio of surface area to volume, and hence reduced cellular surface area contacting the slide in embryos as compared to sperm. Exposure of slides to 100 μg/ml pepsin in 0.01 M HCl [26] permeabilized the cell membrane of embryos to permit labeling without destruction and loss of samples from the slides. We determined that slide preparation for post-implantation (8.5 dpc) conceptuses did not require colcemid for metaphase arrest, thus greatly reducing labor and reagent costs. Adaptation of the preimplantation (4.0 dpc) hybridization technique to the 8.5 dpc and post-natal samples required minimal changes and allowed slides from each of the successive stages to be analyzed in parallel. Consequently, reagent conservation was maximized and results could be rapidly generated in a single hybridization session. We are currently optimizing the use of these probes to identify sex chromosomes at other important stages of mouse development, including the zygote stage (both before and after the pronuclei have converged).

The accuracy of the XY FISH method in this study was confirmed by existing PCR techniques [15,16]. These and other PCR techniques provided rapid, reliable indication of gender in mice, and in our laboratory, have been reliable. However, as described earlier, gametes and developing conceptuses can pose unique problems for PCR sex determination. For example, the amount of nuclear material may be small and require extensive rounds of amplification. Seidel [38] in his excellent review of techniques for sexing mammalian spermatozoa and conceptuses, stated that PCR amplification of Y-specific DNA (e.g. sry) has the potential to yield ‘‘false female’’ samples where DNA amounts are limiting. False positives may be avoided with the use of additional autosomal primers as positive controls in multiplex PCR reactions [39], but this adds to the complexity and cost of the analysis. A second difficulty encountered with PCR is when maternal cells contaminate the sample, as can occur after the conceptus has implanted into the uterine wall. The simplex PCR reaction developed by Clapcote and Roder [15] permits simultaneous amplification of fragments of X and Y chromosomes, but in our experience, addition of increasing quantities of maternal DNA to embryonic male samples quickly led to presence of a dominant X chromosome-specific Jarid1c PCR band and apparent loss of a visible Y-specific band (data not shown). Although probes for FISH analysis are costly, application of 50 conceptuses or more to a single slide can reduce the price on a per-sample basis (approx $5 USD), approximately equivalent to current PCR per-sample estimates. Although the FISH analysis may initially require slightly more labor and optimization, with proper training the time difference between PCR and FISH analysis can be minimized. Although both methods are quite robust, FISH may have an advantage over PCR in terms of accuracy [19,21] and in minimizing false positives that arise from contamination by maternal tissue.

In human medicine, FISH identification of the X and Y chromosome has been employed to determine the genetic sex of babies that have ambiguous genitalia [40–42]. Various mutant mice strains and domestic animals may also have ambiguous genitalia at birth [43] and provide an additional application for, XY FISH analysis. Our current research is aimed at determining how environmental factors, and particularly maternal diet, might influence sex ratio skewing among litters in mice where sexing based on anogenital distance may not always be reliable [44]. The FISH technology described here has been developed to allow us to accomplish each of these objectives efficiently and with confidence in the outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the financial support of the National Institutes of Heath (grant number HD044042-02 to RMR and CSR). Helpful recommendations on FISH analysis of sperm cells was provided by Drs. Andrew Wyrobek and Francesco Marchetti of the Biosciences Directorate, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore CA, USA and the laboratory of James A. Birchler, in particular, Dr. Jonathan Lamb, University of Missouri-Columbia, MO, USA. Generous advice on sperm preparation for FISH was provided by Ms. Evelyn Ko, Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, AB, Canada. Assistance with animal husbandry and FISH micrograph documentation was provided by Ms. Emily Fountain, Ms. Stefanie Blevins, and Mr. Cory Weimer, University of Missouri-Columbia, MO, USA.

References

- 1.Rosenfeld CS, Grimm KM, Livingston KA, Brokman AM, Lamberson WE, Roberts RM. Striking variation in the sex ratio of pups born to mice according to whether maternal diet is high in fat or carbohydrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4628–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0330808100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenfeld CS, Roberts RM. Maternal diet and other factors affecting offspring sex ratio: a review. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:1063–70. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.030890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimura K, Spate LD, Green MP, Roberts RM. Effects of D-glucose concentration, D-fructose, and inhibitors of enzymes of the pentose phosphate pathway on the development and sex ratio of bovine blastocysts. Mol Reprod Dev. 2005;72:201–7. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.vom Saal FS. Sexual differentiation in litter-bearing mammals: influence of sex of adjacent fetuses in utero. J Anim Sci. 1989;67:1824–40. doi: 10.2527/jas1989.6771824x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickerson RL, McMurry CS, Smith EE, Taylor MD, Nowell SA, Frame LT. Modulation of endocrine pathways by 4,4′-DDE in the deer mouse Peromyscus maniculatus. Sci Total Environ. 1999;233:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(99)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharpe RM. Pathways of endocrine disruption during male sexual differentiation and masculinization. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;20:91–110. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wisniewski AB, Cernetich A, Gearhart JP, Klein SL. Perinatal exposure to genistein alters reproductive development and aggressive behavior in male mice. Physiol Behav. 2005;84:327–34. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes BM. Birth order and locus of control revisited: sex of siblings as a moderating factor. Psychol Rep. 2005;97:419–22. doi: 10.2466/pr0.97.2.419-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viger RS, Silversides DW, Tremblay JJ. New insights into the regulation of mammalian sex determination and male sex differentiation. Vitam Horm. 2005;70:387–413. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(05)70013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotinot C, Pailhoux E, Jaubert F, Fellous M. Molecular genetics of sex determination. Semin Reprod Med. 2002;20:157–68. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bronshtein M, Rottem S, Yoffe N, Blumenfeld Z, Brandes JM. Early determination of fetal sex using transvaginal sonography: technique and pitfalls. J Clin Ultrasound. 1990;18:302–6. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870180414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colby LA, Morenko BJ. Clinical considerations in rodent bioimaging. Comp Med. 2004;54:623–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mantzaris D, Cram D, Healy C, Howlett D, Kovacs G. Preliminary report: correct diagnosis of sex in fetal cells isolated from cervical mucus during early pregnancy. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;45:529–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2005.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradbury MW, Isola LM, Gordon JW. Enzymatic amplification of a Y chromosome repeat in a single blastomere allows identification of the sex of preimplantation mouse embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4053–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clapcote SJ, Roder JC. Simplex PCR assay for sex determination in mice. Biotechniques. 2005;38:702–6. doi: 10.2144/05385BM05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramalho MF, Garcia JM, Esper CR, Vantini R, Alves BC, Almeida Junior IL, Hossepian de Lima VF, Moreira-Filho CA. Sexing of murine and bovine embryos by developmental arrest induced by high-titer H-Y antisera. Theriogenology. 2004;62:1569–76. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold KE, Orr KJ, Griffiths R. Primary sex ratios in birds: problems with molecular sex identification of undeveloped eggs. Mol Ecol. 2003;12:3451–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.02007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson BC, Gemmell NJ. PCR-based sexing in conservation biology: wrong answers from an accurate methodology? Conserv Genet. 2006;7:267–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato T, Ikuta K, Sherlock J, Adinolfi M, Suzumori K. Comparison between fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and quantitative-fluorescent polymerase chain reaction (QF-PCR) for the detection of aneuploidies in single blastomeres. Prenat Diagn. 2003;23:678–84. doi: 10.1002/pd.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wyrobek AJ, Schmid TE, Marchetti F. Cross-species sperm-FISH assays for chemical testing and assessing paternal risk for chromosomally abnormal pregnancies. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2005;45:271–83. doi: 10.1002/em.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gimenez C, Egozcue J, Vidal F. Sexing sibling mouse blastomeres by polymerase chain reaction and fluorescent in-situ hybridization. Hum Reprod. 1994;9:2145–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheung-Flynn J, Prapapanich V, Cox MB, Riggs DL, Suarez-Quian C, Smith DF. Physiological role for the cochaperone FKBP52 in androgen receptor signaling. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1654–66. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lei ZM, Mishra S, Zou W, Xu B, Foltz M, Li X, Rao CV. Targeted disruption of luteinizing hormone/human chorionic gonadotropin receptor gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:184–200. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.1.0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagy A, Gertsenstein M, Vintersten K, Behringer R. Manipulating the mouse embryo: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ko E, Rademaker A, Martin R. Microwave decondensation and codenaturation: a new methodology to maximize FISH data from donors with very low concentrations of sperm. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2001;95:143–5. doi: 10.1159/000059336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coonen E, Dumoulin JC, Ramaekers FC, Hopman AH. Optimal preparation of preimplantation embryo interphase nuclei for analysis by fluorescence in-situ hybridisation. Hum Reprod. 1994;9:533–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conlon RA. Whole-mount in situ hybridization to mouse embryos. In: Kreig PA, editor. A laboratory guide to RNA: isolation, analysis, and synthesis. 1. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1996. pp. 371–80. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eicher EM, Washburn LL. Assignment of genes to regions of mouse chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:946–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.2.946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wyrobek AJ, Alhborn T, Balhorn R, Stanker L, Pinkel D. Fluorescence in situ hybridization to Y chromosomes in decondensed human sperm nuclei. Mol Reprod Dev. 1990;27:200–8. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080270304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adler ID, Bishop J, Lowe X, Schmid TE, Schriever-Schwemmer G, Xu W, Wyrobek AJ. Spontaneous rates of sex chromosomal aneuploidies in sperm and offspring of mice: a validation of the detection of aneuploid sperm by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Mutat Res. 1996;372:259–68. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(96)00145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marchetti F, Lowe X, Moore DH, 2nd, Bishop J, Wyrobek AJ. Paternally inherited chromosomal structural aberrations detected in mouse first-cleavage zygote metaphases by multicolour fluorescence in situ hybridization painting. Chromosome Res. 1996;4:604–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02261723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zwingman T, Erickson RP, Boyer T, Ao A. Transcription of the sex-determining region genes Sry and Zfy in the mouse pre-implantation embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:814–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Passera L, Aron S, Vargo EL, Keller L. Queen control of sex ratio in fire ants. Science. 2001;293:1308–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1062076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zar JH. Biostatistical analysis. 4. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenlee AR, Krisher RL, Plotka ED. Rapid sexing of murine preimplantation embryos using a nested, multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) Mol Repod Dev. 1998;49:261–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199803)49:3<261::AID-MRD6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McClive PJ, Sinclair AH. Rapid DNA extraction and PCR-sexing of mouse embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;60:225–6. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marchetti F, Lowe X, Bishop J, Wyrobek AJ. Absence of selection against aneuploid mouse sperm at fertilization. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:948–54. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.4.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seidel GE., Jr Sexing mammalian spermatozoa and embryos—state of the art. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1999;54:477–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kunieda T, Xian M, Kobayashi E, Imamichi T, Moriwaki K, Toyoda Y. Sexing of mouse preimplantation embryos by detection of Y chromosome-specific sequences using polymerase chain reaction. Biol Reprod. 1992;46:692–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod46.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quaife R, Leong SH, Yip CL, Chan KH. Twenty-four hour, non-invasive, neonatal chromosome analysis—application in a case of mixed gonadal dysgenesis. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29:669–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sultan C, Paris F, Jeandel C, Lumbroso S, Galifer RB. Ambiguous genitalia in the newborn. Semin Reprod Med. 2002;20:181–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohammed F, Tayel SM. Sex identification of normal persons and sex reverse cases from bloodstains using FISH and PCR. J Clin Forensic Med. 2005;12:122–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcfm.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haqq CM, Donahoe PK. Regulation of sexual dimorphism in mammals. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:1–33. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenham LW, Greenham V. Sexing mouse pups. Lab Anim. 1977;11:181–4. doi: 10.1258/002367777780936620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]