It has been reported that human T cell lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV‐I) infection is related to a wide range of ocular disorders, such as intraocular lymphoma,1,2 uveitis,3 and cytomegalovirus (CNV) retinitis.4 The diagnosis of adult T cell leukaemia (ATL) cell infiltration in the eye is often difficult, even when characteristic ocular findings are present and cytological examinations of intraocular fluids are performed. It is well known that determination of patient serum interleukin 2 receptor alpha (sIL‐2Rα) levels is critical in the evaluation of the clinical status of the disease.5 We report here a patient with systemic ATL who developed vitreous opacities and subretinal lesions and in whom vitreous measurement of the soluble form of sIL‐2Rα provided information that could be used in making a diagnosis and in treating associated ocular disorders.

Case report

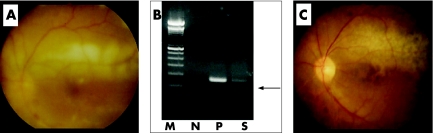

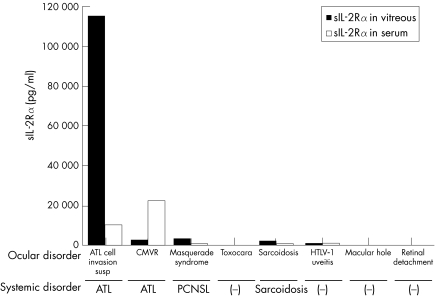

A 69 year old man with a 2 year history of systemic ATL developed a sudden onset of decreased vision and vitreous floaters in the left eye. Funduscopic examination of the left eye revealed dense vitreous opacities and whitish retinal exudates along with superior vascular arcade (fig 1A). Based on the ocular manifestations and the presence of systemic ATL, intraocular infiltration of ATL cells was suspected and a diagnostic pars plana vitrectomy was performed in the left eye. After informed consent was obtained, a vitreous sample from the patient was analysed using research protocol. The cytopathology of the vitreous sample was class III with many atypical lymphoid cells. The extra cell pellet of the sample was used for polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Proviral DNA for the HTLV‐I tax gene was amplified using previously described PCR methods.3 The proviral DNA was amplified by PCR (fig 1B). We also examined detection of CMV‐DNA using quantitative PCR, because diffuse dot retinal haemorrhages like a CMV retinitis were seen in the left eye. The result of quantitative PCR was undetectable levels in the vitreous. Since the HTLV‐I tax gene was detected in the vitreous sample, the vitreous fluid was assayed for sIL‐2Rα levels using ELISA (R&D system, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Data for the vitreous samples of seven patients with various retinal disorders, who served as controls, can be seen in figure 2. In this patient, the concentrations of sIL‐2Rα were extremely high (115 114 pg/ml) in the vitreous and considerably high in the serum. The concentrations of sIL‐2Rα in the vitreous and the serum of another ATL patient with CMV retinitis, in a patient with intraocular B cell lymphoma, and in a patient with sarcoidosis or HTLV‐I associated uveitis (HTLV‐I carrier, no ATL) were also high, although the concentrations were much less than that observed in the vitreous of this case (fig 2). In addition, detectable levels of sIL‐2Rα were not observed in patients with toxocariasis, idiopathic macular hole or non‐PVR retinal detachment.

Figure 1 Fundus photographs and PCR results. (A) Fundus photograph showing retinal whitish lesions along retinal vessels and dense vitreous opacities. (B) Detection of proviral DNA of HTLV‐I tax gene in vitreous of our ATL patient. M, molecular size marker, N, negative control, P, positive control (HTLV‐I infected cells), S, vitreous sample of our ATL patient. (C) Fundus photograph after treatment with chemotherapy of anticancer medication and CHOP therapy. The cells are not present.

Figure 2 Soluble IL‐2 receptor alpha (sIL‐2Rα) concentrations in the vitreous and the serum of patients with various ocular diseases. CMVR, cytomegarovirus retinitis; ATL, adult T cell leukaemia/lymphoma; PCNSL, primary central nervous system lymphoma (malignant B cell lymphoma); Toxocara, toxocariasis; HTLV‐I uveitis, HTLV‐I associated uveitis; Macular hole, idiopathic macular hole.

Our ATL patient had received conventional CHOP therapy before observation of the ocular symptoms. After identification of the ocular ATL infiltrates and documentation of sIL‐2Rα, a cerebrospinal injection of anticancer medication containing a combination of methotrexate, cytarabine, and prednisolone was added to the CHOP therapy because the patient had central nervous system involvement. One month later, a dramatic improvement was noted in the patient with regard to the retinal exudates and haemorrhages (fig 1C).

Comment

In the current case, the sIL‐2Rα level was much higher than the level observed in the serum or in the vitreous of patients with other retinal disorders. These data strongly suggest that the infiltrating T cell leukaemic cells constitutively express IL‐2Rα on their surface, and secrete soluble forms of IL‐2Rα into the vitreous. Also, the results of this case suggest that the measurement of sIL‐2Rα in the vitreous could be a useful tool in the diagnosis of direct invasion of ATL in the eye, which is critical in the prognosis for the eye and for death.

HTLV‐I infection is endemic in Japan, the Caribbean islands, and South America. Known ophthalmic manifestations of HTLV‐I include malignant infiltrates in patients with ATL, neuro‐ophthalmic disorders, and HTLV‐I associated uveitis. Most of the published information on HTLV‐I ocular manifestations comes from cases in south western Japan, which currently has the highest incidence of infection worldwide. Routine evaluation of HTLV‐I infected patients is important because immune mediated or neoplastic ocular involvement may occur during the course of the disease. In different populations, genetic and environmental factors may also have a role in the ocular manifestations of HTLV‐I.

Unlike ocular ATL infiltrates, HTLV‐I associated uveitis is not a serious disorder, as this condition is responsive to corticosteroid therapy. However, since patients with ATL infected by HTLV‐I are immunocompromised and subject to invasion of retinal lesions1,2 and cytomegalovirus retinitis,4 early diagnosis and treatment are very important. In the present ATL case, the early diagnosis helped to ensure that the patient was able to receive an appropriate course of therapy.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Duco Hamasaki for critical reading of this manuscript. Partial financial support was from Scientific Research (B) 1437055 of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

References

- 1.Hirata A, Miyazaki T, Tanihara H. Intraocular infiltration of adult T‐cell leukemia. Am J Ophthalmol 2002134616–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar S R, Gill P S, Wagner D G.et al Human T‐cell lymphotropic virus type I‐associated retinal lymphoma. A clinicopathologic report. Arch Ophthalmol 1994112954–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sagawa K, Mochizuki M, Masuoka K.et al Immunopathological mechanisms of human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV‐I) uveitis; detection of HTLV‐I‐ infected T cells in the eye and their constitutive cytokine production. J Clin Invest 199595852–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mori N, Ura K, Murakami S.et al Adult T cell leukemia with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Rinsho Ketsueki 199233537–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamaguchi K, Nishimura Y, Kiyokawa T.et al Elevated serum levels of soluble interleukin‐2 receptors in HTLV‐I‐associated myelopathy. J Lab Clin Med 1989114407–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]