Abstract

Aims

To summarise the results of visual performance tests and other data of institutionalised people with intellectual disability referred to a visual advisory centre (VAC) between 1993 and 2003, and to determine trends in these data.

Methods

A retrospective medical record review was undertaken of 6220 consecutive people examined ophthalmologically according to a standard protocol by one VAC that specialised in visual assessment and treatment of people with intellectual disability, between 1993 and 2003. χ2 test for linear trend was used and linear regression coefficients were calculated.

Results

The proportion of people aged ⩾50 years increased from 19.3% to 34.2% between 1995 and 2003 (p<0.001); the combined figure of severe or profound intellectual disability decreased from 80.0% to 52.6% (p<0.001); the proportion of mobile people increased from 52.1% to 98.0% (p<0.001); the combined proportion of people with visual impairment or blindness decreased from 70.9% to 22.9% (p<0.001), and that of people with visual disorders decreased from 89.6% to 75.3% (p<0.001). Causes of intellectual disability were identified in 58.4% people; 20.8% had Down's syndrome.

Conclusion

Many ocular diagnoses were found, indicating the need for ophthalmological monitoring. Specialised centres are helpful, because assessment and treatment of people with intellectual disability is complicated and time consuming. Protocols for efficient referral will have to be developed. A major task lies ahead to improve the treatment rates of refractive errors, cataract and strabismus, and to find specific causes of intellectual disability.

Visual impairment and blindness are highly prevalent among institutionalised people with intellectual disability.1 Visual problems often remain unrecognised in people with intellectual disability, because identifying visual problems in this group is difficult and these people rarely mention them spontaneously. Treatment and knowledge of visual problems can have positive effects on behaviour and development.2,3,4,5 Therefore, regular assessment of visual acuity and visual fields is recommended.6

The present study is focused on an institutionalised population of 6220 people with intellectual disability who were referred for visual assessment between 1993 and 2003. The aim of this study is to summarise the demographic data, degree of intellectual disability, mobility, visual impairment and blindness, causes of intellectual disability, visual disorders and comorbidity, and to identify trends in these data over an 11‐year period.

Materials and methods

Population

We retrospectively reviewed the records of 6220 consecutive people examined by the visual advisory centre (VAC) of Bartiméus, Zeist, The Netherlands, from 1 January 1993 to 31 December 2003. Bartiméus is a Dutch institution providing education, care and services to the blind and those with partial sight. The VAC was started in 1991 to identify visual problems in institutionalised people with intellectual disability, to provide information and to explore the possibilities of treatment. The first two years were omitted from the report because of small numbers of people and incomplete registration.

All subjects were people with intellectual disability living in institutions and were referred to the VAC by doctors specialised in their care. Doctors were responsible for selecting those people who could benefit from the VAC expertise—for example, those who were difficult to assess or had reduced visual performance. The ethics committee (Bartiméus, Doorn, The Netherlands) approved the study. Participants or their caretakers gave consent.

Measurements

Trained optometrists and an ophthalmologist (NTT) examined the participants ophthalmologically according to a standard protocol. Full assessment required 90 min.

Referring doctors provided personal data, data on mobility, degree and cause of intellectual disability, and medical history. Optometrists tested visual performance by assessing visual acuity and visual fields. Visual acuity was mainly binocularly measured because monocular acuity testing was often not tolerated. This had no influence on the classification of visual impairment, as acuity of the best eye was used. Visual acuity was assessed with two tests if possible: Snellen chart, Stycar or Lea Hyvärinen, and Teller or Cardiff acuity cards. The results were expressed in Snellen equivalents.

Visual fields were assessed using the confrontational method with Stycar balls. Eye movements and external eye structures were observed. The anterior segment was examined using a handheld slit lamp. Refraction was determined by retinoscopy without mydriasis.

Ophthalmological assessment by the ophthalmologist included funduscopy and retinoscopy in mydriasis, and was carried out when the cause of visual impairment was uncertain, when the question of cataract surgery arose or when retinoscopy without mydriasis seemed unreliable.

Inter‐rater variability was minimal in a previous study on visual impairment among people with intellectual disability in The Netherlands, in which optometrists from the same institution as in our study carried out the assessments.7 We therefore also assumed that inter‐rater variability would be minimal in our study.

Definitions

-

Degree of intellectual disability: defined according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th edition TR classification8:

-

-

Mild, IQ 55–70;

-

-

Moderate, IQ 35–55;

-

-

Severe, IQ 25–35;

-

-

Profound, IQ <25.

-

-

-

Mobility:

-

-

Mobile, could move around independently with or without wheelchair or aids;

-

-

Immobile, unable to move around independently.

-

-

-

Visual performance: defined according to the World Health Organization criteria, using presenting visual acuity (modified: when visual fields were unknown, visual performance was classified according to visual acuity only; hemianopia was included, because of access to specialised care)9,10:

-

-

Normal vision, visual acuity ⩾0.8 and visual fields >50°;

-

-

Mild vision loss, visual acuity ⩾0.3 and <0.8 and/or visual fields >30° and ⩽50°;

-

-

Moderate to severe vision loss, visual acuity ⩾0.05 and <0.3, and/or visual fields >10° and ⩽30°, and/or left‐sided or right‐sided hemianopia;

-

-

Profound vision loss to near blindness, light perception to visual acuity <0.05, and/or visual fields ⩽10°;

-

-

Blindness, no light perception.

-

-

-

Refractive error: defined using the spherical equivalent of the best eye:

-

-

Emmetropia, spherical equivalent ⩾−1D and ⩽+1D,

-

-

Myopia, spherical equivalent <−1D;

-

-

Severe myopia, spherical equivalent ⩽−5D;

-

-

Hyperopia, spherical equivalent >+1D;

-

-

Severe hyperopia, spherical equivalent ⩾+5D.

-

-

Hearing impairment: defined as a loss of ⩾35 dB.11

Statistical analyses

Demographic data, visual assessment data, causes of intellectual disability, visual disorders and comorbidity were analysed using SPSS V.10.1 and Microsoft Excel V.2002. Only data at first presentation were used. People with missing data were excluded from the analyses. When relevant, the χ2 test for linear trend was used to assess general trends between 1993 and 2003. Linear regression analyses were used to provide coefficients (B) for significant trends; only values of p<0.05 are reported. The best value of visual acuity, visual disorders of both eyes and refractive error of the best eye were used in the analyses.

Results

Population

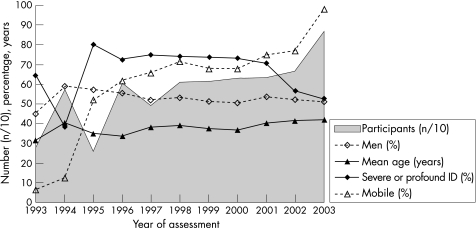

Figure 1 shows trends in number of participants, sex, age, degree of intellectual disability and mobility, according to year of assessment. The number of participants showed a more than threefold increase between 1993 and 2003. The percentage of men was 52.7% (3275/6217) and varied between 44.9% and 58.6%. Mean age was 38.5 years (range 1.6 months–92.2 years) and increased from 35.0 to 41.9 years between 1995 and 2003 (p<0.001, B = +0.91 years per year). The percentage of participants ⩾50 years old was 23.5% (1460/6220) and increased from 19.3% to 34.2% between 1995 and 2003 (not shown in the figure; p<0.001, B = +1.8% per year).

Figure 1 Trends in number of participants (n = 6220), sex (% male; n = 6217), mean age (years; n = 6211), degree of intellectual disability (% combined severe and profound intellectual disability (ID); n = 2906) and mobility (% mobile; n = 4987), according to year of assessment.

Degree of intellectual disability was reported in 46.7% (2906/6220) of participants, of whom 63.1% (1834/2906) had severe or profound disability. This combined figure was 70.6–80.0% between 1995 and 2001, and decreased to 52.6% in 2003 (p<0.001, B = −4.7% per year). Mobility was noted in 80.2% (4987/6220) of participants, of whom 71.6% (3571/4987) were mobile. The percentage of mobile participants increased from 52.1% to 98.0% between 1995 and 2003 (p<0.001, B = +4.4% per year).

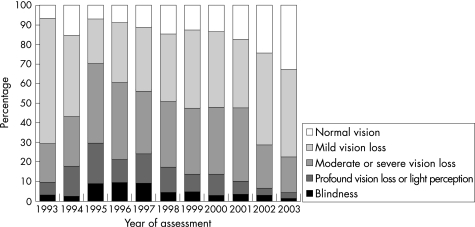

Visual impairment and blindness

Visual performance could be determined in 96.9% (6030/6220) of all participants, of whom 98.0% (5912/6030) were classified according to visual acuity and 2.0% (118/6030) according to visual fields. Moderate vision loss to blindness was present in 43.8% (2642/6030) of participants (table 1), and showed a steady decline from 70.9% to 22.9% between 1995 and 2003 (p<0.001, B = −5.4% per year; fig 2).

Table 1 Presenting visual acuity, visual fields and visual performance of people with intellectual disability (96.9%, 6030/6220).

| Presenting visual acuity | Total (%) | Visual fields | Total (%) | Visual performance | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ⩾0.8 | 1036 (17.2) | >50° | 4453 (84.5) | Normal vision | 1004 (16.7) |

| 0.30–0.80 | 2440 (40.5) | >30–50° | 446 (8.5) | Mild vision loss | 2384 (39.5) |

| 0.05–0.30 | 1720 (28.5) | >10–30° | 265 (5.0) | Moderate to severe vision loss | 1784 (29.6) |

| LP–0.05 | 521 (8.6) | ⩽10° | 107 (2.0) | Profound vision loss to LP | 604 (10.0) |

| NLP | 312 (5.2) | Blindness | 254 (4.2) | ||

| Total | 6029 | Total | 5271 | Total | 6030 |

LP, light perception; NLP, no light perception.

Figure 2 Trends in visual performance (%) of people with intellectual disability (6030/6220 = 96.9%), according to year of assessment.

Causes of intellectual disability

Data on causes of intellectual disability, visual disorders and comorbidity were known for 83.7% (5205/6220) of participants; the other 16.3% received only a basic visual assessment without need for further exploration.

A specific cause of intellectual disability was reported in 58.4% (3039/5205) of participants (table 2). This percentage varied between 50.6% and 71.2% during the 11‐year period. Down's syndrome was the most frequent cause of intellectual disability. More than one cause of intellectual disability was found in 7.2% (219/3039) of cases. Causes varied over time, but no trends were discernable.

Table 2 Specific causes (%) of intellectual disability (n = 5205).

| Causes of intellectual disability | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Down's syndrome | 1081 (20.8) |

| Rett syndrome | 71 (1.4) |

| Angelman's syndrome | 52 (1.0) |

| Tuberous sclerosis | 41 (0.8) |

| Fragile‐X syndrome | 24 (0.5) |

| Prader–Willi syndrome | 12 (0.2) |

| West's syndrome | 12 (0.2) |

| Cornelia de Lange syndrome | 11 (0.2) |

| Cri‐du‐chat syndrome | 10 (0.2) |

| Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome | 10 (0.2) |

| Williams syndrome | 8 (0.2) |

| Neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen's disease) | 8 (0.2) |

| Aicardi syndrome | 7 (0.1) |

| CHARGE association | 7 (0.1) |

| Turner syndrome | 6 (0.1) |

| Klinefelter's syndrome | 5 (0.1) |

| Sotos' syndrome | 5 (0.1) |

| Usher's syndrome | 5 (0.1) |

| Other | 145 (2.8) |

| Chromosomal aberration, unspecified | 61 (1.2) |

| Total hereditary causes | 1581 (30.4) |

| Perinatal causes (including perinatal bad condition, anoxia, asphyxia, birth trauma, haemorrhage) | 644 (12.4) |

| Meningoencephalitis | 267 (5.1) |

| Congenital infection, including | 83 (1.6) |

| Rubella | 37 (0.7) |

| Toxoplasmosis | 21 (0.4) |

| Cytomegalovirus | 15 (0.3) |

| Other or unspecified | 10 (0.2) |

| Total infectious causes | 349 (6.7) |

| Congenital hypothyroidy | 21 (0.4) |

| Phenylketonuria | 20 (0.4) |

| Mucopolysaccharidosis | 12 (0.2) |

| Other | 18 (0.3) |

| Unspecified | 31 (0.6) |

| Total metabolic causes | 97 (1.9) |

| Congenital anatomical brain anomalies | 311 (6.0) |

| Prematuritas | 169 (3.2) |

| Trauma with hypoxia or anoxia | 84 (1.6) |

| Kernicterus | 35 (0.7) |

| Dysmaturitas | 19 (0.4) |

| Malignant brain tumour | 8 (0.2) |

| Toxicosis of pregnancy | 4 (0.1) |

| Total other causes | 597 (11.5) |

| Unknown cause | 2166 (41.6) |

| Total of all participants | 5205 |

Sum of causes may exceed the respective total owing to multicausality.

Visual disorders

Visual disorders were reported in 79.9% (4157/5205) of participants. The most frequent were strabismus, refractive errors, cataract, nystagmus and cerebral visual impairment (CVI; table 3). These percentages were compared with percentages in the total population with intellectual disability and with percentages in the general population.1,5,7,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50

Table 3 Visual disorders (%) among (n = 5205) people with intellectual disability.

| Visual disorder | This study | Population with intellectual disability | General population |

|---|---|---|---|

| total (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| No visual disorder | 1048 (20.1) | 32.5–69.4 | − |

| Strabismus | 2189 (42.1) | 0.5–44.1 | 1.1–4.0 |

| Myopia | 1186 (22.8) | 6–37 | 1.4–48.1 |

| Moderate | 629 (12.1) | 10–25 | 4.3–33 |

| Severe | 557 (10.7) | 3.6–27 | 1.3–7 |

| Hyperopia | 672 (12.9) | 8–52 | 1.3–57.0 |

| Moderate | 556 (10.7) | 24–45 | 30.6–42.2 |

| Severe | 116 (2.2) | 1–7 | 0.13–3 |

| Cataract | 1270 (24.4) | 2–86 | 0.005–57.6 |

| VA ⩾0.3 | 428 (8.2) | – | – |

| VA <0.3 | 497 (9.5) | – | – |

| Past cataract surgery | 345 (6.6) | 0.9–11 | – |

| Nystagmus | 1002 (19.3) | 0.3–20 | <0.001–0.083 |

| Cerebral visual impairment | 994 (19.1) | 0.7–12.6 | 0.008–0.058 |

| Keratoconus | 309 (5.9) | 0.1–15 | 0.05–<0.1 |

| Optic nerve atrophy | 203 (3.9) | 2.3–24 | 0.019–0.13 |

| Retinal detachment | 107 (2.1) | 0.7–1.3 | <0.001–0.012 |

| Atrophic bulbus or enucleation | 79 (1.5) | – | – |

| Glaucoma | 47 (0.9) | 1.1–9 | <0.001–8.6 |

| An/microphthalmos | 45 (0.9) | 0.7–5 | 0.002–0.014 |

| Tapetoretinal degeneration | 45 (0.9) | 0.7–4 | 0.003–0.027 |

| Coloboma | 35 (0.7) | 0.8–3 | 0.001 |

| Microcornea | 29 (0.6) | 2.3 | – |

| Macular degeneration | 19 (0.4) | 0.7–11 | 0.01–40.6 |

| Buphthalmus | 8 (0.2) | – | – |

| Contusion of eyeball | 6 (0.1) | – | – |

| Aniridia | 3 (0.1) | – | 0.001–0.002 |

| Total of all participants | 5205 | – | – |

Sum of visual disorders may exceed the respective total owing to occurrence of multiple disorders.

VA, visual acuity.

CVI was present in 37.6% (822/2186) of participants with visual acuity <0.3, in 31.2% (210/673) of young participants (0–20 years old), and in 13.6% (343/2519) of participants aged ⩾40 years. Retinoscopy was successful in 70.1% (3648/5205) of participants.

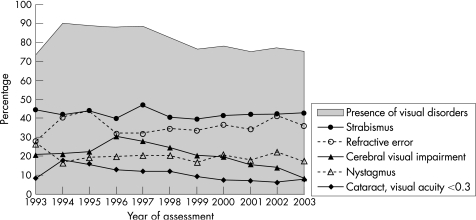

Visual disorders were present in 87.4–88.8% of participants between 1995 and 1997, and declined to 75.0–77.9% between 1999 and 2003 (p<0.001, B = −1.9% per year; fig 3). CVI declined from 30.3% to 8.5% between 1996 and 2003 (p<0.001, B = −3.0% per year) and cataract with visual acuity <0.3 declined from 17.8% to 7.7% between 1994 and 2003 (p<0.001, B = −1.1% per year). Strabismus (range 39.5–46.8%), refractive errors (range 27.8–44.0%) and nystagmus (range 16.5–26.4%) varied over time, but showed no specific trends.

Figure 3 Trends in visual disorders (%) among people with intellectual disability (n = 5205), according to year of assessment.

Comorbidity

Comorbidity was present in 57.9% (3014/5205) of participants (table 4). The most frequent comorbidities were motor disability (range 24.9–39.6%), epilepsy (range 12.0–32.9%) and hearing impairment (range 4.2–19.5%). Self‐mutilation of the eyes was seen in 5.4% (range 1.6–7.6%) of participants. No trends over time could be discerned.

Table 4 Comorbidity (%) among people with intellectual disability (n = 5205).

| Comorbidity | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Motor retardation | 1675 (32.2) |

| Epilepsy | 1428 (27.4) |

| Hearing impairment (⩾35 dB) | 647 (12.4) |

| Ocular self‐mutilation | 282 (5.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 61 (1.2) |

| Autism | 48 (0.9) |

| Congenital cor vitium | 46 (0.9) |

| Hypothyroidism, acquired | 40 (0.8) |

| No comorbidity | 2191 (42.1) |

| Total of all participants | 5205 |

Sum of comorbidity may exceed the total owing to multiple reasons of comorbidity.

Discussion

This study on 6220 people with intellectual disability referred for visual assessment showed a steady decline in visual impairment and blindness over time. However, visual disorders remained highly prevalent. The proportion of older and mobile participants increased, and that of participants with severe or profound intellectual disability decreased. Specific causes of intellectual disability were reported in 58.4% (3039/5205) of participants.

Bias

Bias in the results of this study cannot be excluded. This is due to incomplete registration in the earlier years; these data were irretrievable.

Visual acuity was assessed with tests that are not completely comparable. However, using these different tests was the best that could be achieved in our population. The best value of visual acuity was used to classify visual impairment, without differentiating between distant and near acuity. We thought this acceptable, because near vision is the most important for most people with intellectual disability, especially for those having lower levels of functioning. The confrontational method for visual field assessment provides only an indication of the actual visual fields.

Data on causes of intellectual disability, visual disorders and comorbidity were collected from 84% of participants for whom further examination was needed. This group was more often visually impaired or blind than the other 16% (42.4% v 36.1%) and was expected to have more visual disorders.

Retinoscopy was successful in 70% (3648/5205) of participants. A refractive error was found in 50.6% (1845/3648) of these people. Unsuccessful retinoscopy was seen in people with severe or profound intellectual disability, with CVI or with visual acuity <0.3.

Hearing impairment was defined as a loss of ⩾35 dB in our study. This differs from the definition currently used for people with intellectual disability in The Netherlands, which also includes a mild loss of ⩾25 dB.11 People with a loss of 25–35 dB could not be identified.

Interpretation

The threefold increase in examined people in the 11‐year period is a result of increased awareness of visual impairment among caretakers and increased capacity of the VAC. Almost 25% of participants were aged ⩾50 years, which confirms previous findings of longer life expectancy of people with intellectual disability.19,51,52,53 Severity of intellectual disability decreased, which may be explained by the fact that institutions with people with higher levels of functioning were referring at a later period. Increased mobility is partly caused by activation programmes.

We used presenting visual acuity in our classification, because it describes how people live their lives. A steady decline in visual impairment and blindness could be observed. The explanation might be the following. Initially, attention was focused on people with a high probability of visual impairment or blindness. Over time, the backlog of people with more severe disability became exhausted and attention shifted to those with less visual impairment. Increased awareness of the presence of visual problems among caretakers, and increased awareness of the importance of visual assessment and treatment, may have contributed to the increase in subnormal vision. Difficulties in discriminating between visual problems, intellectual disability and behavioural problems may have played a part in referral.

Despite progress in clinical investigations, no specific cause of intellectual disability was reported in >40% of people. The presence of visual disorders declined with time. This was most obvious for CVI, which was correlated to visual impairment. CVI was less often diagnosed in older people, because age‐related causes of visual impairment made differentiating these people from those with CVI more difficult and because they were born before modern techniques could keep so many premature infants with brain damage alive. Refractive errors were split into subcategories, as people with moderate myopia will not have problems regarding activities of daily living. Glaucoma was diagnosed in only 0.9% of people, reflecting problems in acceptance of intraocular pressure measurement in people with intellectual disability.

Other studies

Severe or profound intellectual disability was present in 63% of our study population, compared with 55% in the total Dutch institutionalised population with intellectual disability.54 Combined figures for visual impairment and blindness in institutionalised people with intellectual disability, reported in the literature, vary between 18.7% and 37%, compared with 44% in our study population.19,23,35,47,48,55 This could be explained by the preselection by referring doctors. A specific cause of intellectual disability could be established in 58% of people, compared with 41–88.6% in the literature, with highest figures for severe intellectual disability.23,28,56,57,58,59,60 Down's syndrome was reported in 21% of people, which is in accordance with the literature (13.1–29%).23,48,56,57,58,59,61

Visual disorders were difficult to compare with those reported in the literature, because populations varied greatly. They were diagnosed more often in the present study than in the total population with intellectual disability, which could be explained by preselection. Moderate hyperopia was less frequent, which could be related to definition and presbyopia not being included. CVI was related to visual impairment and severe or profound intellectual disability, explaining its higher frequencies in our study. This study confirms that visual disorders are more prevalent among people with intellectual disability than in the general population. Reported figures for the general population varied because of differences in age groups. Self‐mutilation of the eyes was present in 5% of our study population. This is an important observation, because self‐mutilation is a high risk factor for severe ocular morbidity.

The future

Causes of intellectual disability need further investigation, as the cause is still unknown in >40% of people. Doctors specialised in the care of people with intellectual disability and the VAC have to reach a consensus on which people will be referred for assessment and treatment. In this way, those who could benefit most from the VAC expertise will be selected. The completion of qualify of life questionnaires would be valuable for future research, as they provide a more objective measure of therapeutic outcomes. Diagnosis and treatment of strabismus, refractive errors, cataract, ocular self‐mutilation and glaucoma in people with intellectual disability will be a challenge for future studies.

Our study population is not an exact representation of the total institutionalised population with intellectual disability. However, this study showed which changes in population characteristics and visual problems may be expected after the start of large‐scale visual assessment of people with intellectual disability. Although the percentage of people with moderate visual impairment to blindness decreased, >40% still had mild visual impairment. Moreover, visual disorders remained very common. We therefore emphasise the importance of visual and ophthalmological assessment of all people with intellectual disability, including those with minor impairments. Adequate assessment takes 90 min, which is not always possible in general ophthalmological practice. A VAC which is specialised in assessment and treatment of people with intellectual disability is therefore helpful in identification and treatment of visual impairment in this group.

Conclusion

Visual assessment of people with intellectual disability reveals abundant ocular pathology, indicating the need for ophthalmological monitoring. Specialised centres are helpful, because assessment and treatment of people with intellectual disability is complicated and time consuming. Protocols for efficient referral will have to be developed. A major task lies ahead to improve the treatment rates of refractive errors, cataract and strabismus, and to find specific causes of intellectual disability.

Abbreviations

CVI - cerebral visual impairment

VAC - visual advisory centre

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded by Bartiméus, Zeist, The Netherlands.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The Ethics Committee of Bartiméus, Doorn, The Netherlands, approved the research protocol.

Subjects or their caretakers signed an informed consent for us to use their electronic records anonymously for scientific purposes.

References

- 1.Warburg M. Visual impairment in adult people with intellectual disability: literature review. J Intellect Disabil Res 200145424–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castañe M, Peris E. Visual problems in people with severe mental handicap. J Intellect Disabil Res 199337469–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goto S, Yo M, Hayashi T. Intraocular lens implantation in severely mentally and physically handicapped patients. Jpn J Ophthalmol 199539187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagtzaam L M, Evenhuis H M. Directions for active detection of visual disturbances in people with intellectual disability. (In Dutch) Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1999143938–941.10368709 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bothe N, Lieb B, Schafer W D. Development of impaired vision in mentally handicapped children. (In German) Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 1991198509–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evenhuis H M, Nagtzaam L MD , eds. IASSID international consensus statement: early identification of hearing and visual impairment in children and adults with an intellectual disability. Leiden and Manchester: IASSID Special Interest Research Group on Health Issues, 1997 and 1998

- 7.Van Splunder J, Stilma J S, Bernsen R M.et al Prevalence of ocular diagnoses found on screening 1539 adults with intellectual disabilities. Ophthalmology 20041111457–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edn, text revision. Washington, DC: APA, 2000

- 9.Colenbrander A.Visual standards: aspects and ranges of vision loss with emphasis on population surveys. Report prepared for the International Council of Ophthalmology at the 29th International Congress of Ophthalmology. Sydney: International Council of Ophthalmology, 2002

- 10.Anon Definities, epidemiologie en organisatie van de zorg voor blinden en slechtzienden in Nederland. In: De Boer MR, Jansonius NM, Langelaan M, van Rens GHMB, eds. Richtlijn Verwijzing van slechtzienden en blinden. Alphen aan den Rijn: Van Zuiden Communications, 200413–19.

- 11.Evenhuis H M, on behalf of the consensus committee Dutch consensus on diagnosis and treatment of hearing impairment in children and adults with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res 199640451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Apple D J, Ram J, Foster A.et al Cataract: epidemiology and service delivery. Surv Ophthalmol 200045S32–S44. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bianca S, Bianca M. Heart and ocular anomalies in children with Down's syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res 200448281–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blohmé J, Bengtsson‐Stigmar E, Tornqvist K. Visually impaired Swedisch children: longitudinal comparisons 1980–1999. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 200078416–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blohmé J, Tornqvist K. Visual impairment in Swedish children. III. Diagnoses. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 199775681–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catalano R A. Down syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol 199034385–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cregg M, Woodhouse J M, Pakeman V H.et al Accommodation and refractive error in children with Down syndrome: cross‐sectional and longitudinal studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 20014255–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Da Cunha P R, Belmiro de Castro Moreira J. Ocular findings in Down's syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1996122236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evenhuis H M. Medical aspects of ageing in a population with intellectual disability: I. Visual impairment. J Intellect Disabil Res 19953919–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goh P P, Abqariyah Y, Pokharel G P.et al Refractive error and visual impairment in school‐age children in Gombak District, Malaysia. Ophthalmology 2005112678–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haire A R, Vernon S A, Rubinstein M P. Levels of visual impairment in a day centre for people with a mental handicap. J R Soc Med 199184542–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansen E, Flage T, Rosenberg T.et al Visual impairment in Nordic children. III. Diagnoses. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 199270597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haugen O H, Aasved H, Bertelsen T. Refractive state and correction of refractive errors among mentally retarded adults in a central institution. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 199573129–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haugen O H, Hovding G, Riise R. Ocular changes in Down syndrome. (In Norwegian.) Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2004124186–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirvela H, Koskela P, Laatikainen L. Visual acuity and contrast sensitivity in the elderly. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 199573111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isralowitz R, Madar M, Lifshitz T.et al Visual problems among people with mental retardation. Int J Rehabil Res 200326149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwano M, Nomura H, Ando F.et al Visual acuity in a community‐dwelling Japanese population and factors associated with visual impairment. Jpn J Ophthalmol 20044837–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson L. Ophthalmology in mentally retarded adults: a clinical survey. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 198866457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennerley Bankes J L. Eye defects of mentally handicapped children. BMJ 19742533–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klaver C C W, Wolfs R C W, Vingerling J R.et al Age‐specific prevalence and causes of blindness and visual impairment in an older population. Arch Ophthalmol 199816653–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krumpaszky H G, Klauss V. Epidemiology of the causes of blindness. Ophthalmologica 19962101–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kvarnstrom G, Jakobsson P, Lennerstrand G. Visual screening of Swedish children: an ophthalmological evaluation. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 200179240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laatikainen L, Hirvela H. Prevalence and visual consequences of macular changes in a population aged 70 years and older. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 199573105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lambert S R, Drack A V. Infantile cataracts. Surv Ophthalmol 199640427–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCulloch D L, Sludden P A, McKeown K.et al Vision care requirements among intellectually disabled adults: a residence‐based pilot study. J Intellect Disabil Res 199640140–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quigley H A, Broman A T. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol 200690262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabinowitz Y S. Keratoconus. Surv Ophthalmol 199842297–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahi J S, Dezateux C. Epidemiology of visual impairment in Britain. Arch Dis Child 199878381–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raju P, Ramesh S V, Arvind H.et al Prevalence of refractive errors in a rural South Indian population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004454268–4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robaei D, Rose K, Ojaimi E.et al Visual acuity and the causes of visual loss in a population‐based sample of 6‐year‐old Australian children. Ophthalmology 20051121275–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogers M. Visual impairment in Liverpool: prevalence and morbidity. Arch Dis Child 199674299–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shapiro M B, France T D. The ocular features of Down's syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 198599659–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sorsby A, Sheridan M, Leary G A.et al Vision, visual acuity, and ocular refraction of young men: findings in a sample of 1,033 subjects. BMJ 196011394–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group The prevalence of refractive errors among adults in the United States, Western Europe, and Australia. Arch Ophthalmol 2004122495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tuppurainen K. Ocular findings among mentally retarded children in Finland. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 198361634–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Schrojenstein Lantman‐De Valk H M, Metsemakers J F, Haveman M J.et al Health problems in people with intellectual disability in general practice: a comparative study. Fam Pract 200017405–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Schrojenstein Lantman‐de Valk H M, Haveman M J, Maaskant M A.et al The need for assessment of sensory functioning in ageing people with mental handicap. J Intellect Disabil Res 199438289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warburg M. Visual impairment in adult people with moderate, severe, and profound intellectual disability. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 200179450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woodhouse J M, Adler P, Duignan A. Vision in athletes with intellectual disabilities: the need for improved eyecare. J Intellect Disabil Res 200448736–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu T T, Amini L, Leffler C T.et al Cataracts and cataract surgery in mentally retarded adults. Eye Contact Lens 20053150–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patja K, Iivanainen M, Vesala H.et al Life expectancy of people with intellectual disability: a 35‐year follow‐up study. J Intellect Disabil Res 200044591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kommer G J, Stokx L J, Kramers P G N.et alWachtlijstontwikkelingen in de zorg voor verstandelijk gehandicapten: Modellering van de woonzorg voor verstandelijk gehandicapten. Bilthoven: RIVM, 1999

- 53.Van Splunder J, Stilma J S, Bernsen R M D.et al Prevalence of visual impairment in adults with intellectual disabilities in the Netherlands: cross‐sectional study. Eye. Published Online First: 9 September 2005, doi: 10. 1038/sj. eye. 6702059 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Vereniging Gehandicaptenzorg Nederland Landelijke tabellen cliëntenregistraties 2000. Utrecht: SpectraFacility, 2002

- 55.Evenhuis H M, Theunissen M, Denkers I.et al Prevalence of visual and hearing impairment in a Dutch institutionalized population with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res 200145457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arvio M, Sillanpää M. Prevalence, aetiology and comorbidity of severe and profound intellectual disability in Finland. J Intellect Disabil Res 200347108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benassi G, Guarino M, Cammarata S.et al An epidemiological study on severe mental retardation among schoolchildren in Bologna, Italy. Dev Med Child Neurol 199032895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hou J W, Wang T R, Chuang S M. An epidemiological and aetiological study of children with intellectual disability in Taiwan. J Intellect Disabil Res 199842137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Splunder J, Stilma J S, Evenhuis H M. Visual performance in specific syndromes associated with intellectual disability. Eur J Ophthalmol 200313566–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Woodruff M E, Cleary T E, Bader D. The prevalence of refractive and ocular anomalies among 1242 institutionalized mentally retarded persons. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 19805770–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beange H, Taplin J E. Prevalence of intellectual disability in northern Sydney adults. J Intellect Disabil Res 199640191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]