Risk factors for central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) are male gender, psychological stress, type‐A personality, corticoid–steroid treatment and pregnancy. The reason for the presence of male gender as a risk factor is not yet clear. One possibility is a direct influence of androgens. We report a case of a female patient who developed CSCR under testosterone treatment.

Case report

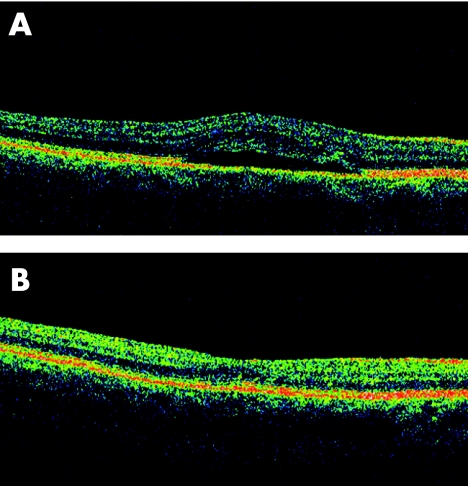

A 45‐year‐old non‐pregnant woman presented with a 1‐day history of metamorphopsia and scotoma in the right eye. She had no eye problems in the past, but her current profession as a manager exposed her to several stress situations. On examination of the right eye, the best‐corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/25; paracentral scotoma and metamorphopsia were confirmed using the Amsler grid. Fundus examination disclosed a neurosensory serous detachment, and fluorescein angiography ruled out choroidal neovascular membrane. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed a typical CSCR (fig 1A). The left eye had a BCVA of 20/20 and did not show any pathology. At the second visit 3 weeks later and on being questioned again, the patient reported that she was on oral testosterone undecanoat 40 mg/day for 2 months because of a general loss of energy and symptoms of fatigue attributed to a low level of endogenous testosterone. At this stage, the plasma‐testosterone level was markedly increased (table 1).

Figure 1 (A) Optical computerised tomography (OCT) confirming serous neurosensory and retinal pigment epithelium detachment in the right eye. (B) OCT of the right eye at 4‐month follow‐up showing reattachment of the retina.

Table 1 Summary of the hormone levels.

| Values on testosterone treatment* | Values after cessation of androgen treatment† | Normal range for females | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total testosterone | 5.30 | 0.69 | 0.5–3.0 nmol/l |

| SHBG | 37 | 141 | 20–118 nmol/l |

| Oestradiol | 73 | 383 | 40–200 pmol/l |

| DHEA‐S | 3.6 | 1.2 | 3–12 μmol/l |

| LH | 60 | 24 | >10 E/l (menopausal) |

| FSH | 56 | 29 | >15 E/l (menopausal) |

DHEA‐S, dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate; FSH, follicle‐stimulating hormones; LH, luteinising hormone; SHBG, sex‐hormone‐binding globulin.

*Oral testosterone undecanoat (40 mg/day).

†Oral oestradiol (1 mg/day).

The testosterone treatment was stopped immediately. Oral oestradiol 1 mg/day was given for climacteric symptoms and for prevention of osteoporosis. This produced an increase in circulating oestradiol levels together with feedback suppression of both gonadotropins, luteinising hormone and follicle‐stimulating hormone, as well as an increase in the sex‐hormone‐binding globulin. Sex‐hormone‐binding globulin enhances the binding of testosterone on this protein, thereby decreasing free circulating testosterone.

At 1 month follow‐up, BCVA was 20/20, and angiography showed no signs of leakage or pigment epithelial detachment. Her blood level of testosterone dropped to values in the lower normal range (table 1). The neurosensory retina was reattached as confirmed by OCT at 4 months (fig 1B).

Comment

The pathogenesis of CSCR is not yet fully understood. It is known, however, that it affects mainly men from 20 to 45 years of age, with type‐A personality, and is often triggered by emotional stress.

Our patient had indeed a type‐A personality and was under professional stress. Nevertheless, we were puzzled to see CSCR in a 45‐year‐old woman who was not hypertensive, pregnant or under steroid treatment. Detailed questioning, however, disclosed testosterone intake. No relapse of CSCR was observed following cessation of testosterone treatment. We assume therefore that the testosterone treatment in this case may have contributed to the disease. We even postulate that a relatively high level of testosterone may be a risk factor for CSCR in general, as androgen receptors have been found in human retinal pigment epithelial cells.1 This hypothesis would also explain the preponderance of males CSCR as well as the with age range of patients by age dependence of testosterone level.2 Further, it is known that subjects with type‐A personality on average have higher testosterone levels,3 which may be further increased under emotional stress.4

Most diseases result from the interplay of many factors. For CSCR, testosterone seems to be one of these acting factors.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Rocha E M, Wickham L A, da Silveira L A.et al Identification of androgen receptor protein and 5alpha‐reductase mRNA in human ocular tissues. Br J Ophthalmol 20008476–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zmuda J M, Cauley J A, Kriska A.et al Longitudinal relation between endogenous testosterone and cardiovascular disease risk factors in middle‐aged men. A 13‐year follow‐up of former Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial participants. Am J Epidemiol 1997146609–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zumoff B, Rosenfeld R S, Friedman M.et al Elevated daytime urinary excretion of testosterone glucuronide in men with the type A behaviour pattern. Psychosom Med 198446223–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King J A, Rosal M C, Ma Y.et al Association of stress, hostility and plasma testosterone levels. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 200526355–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]