Abstract

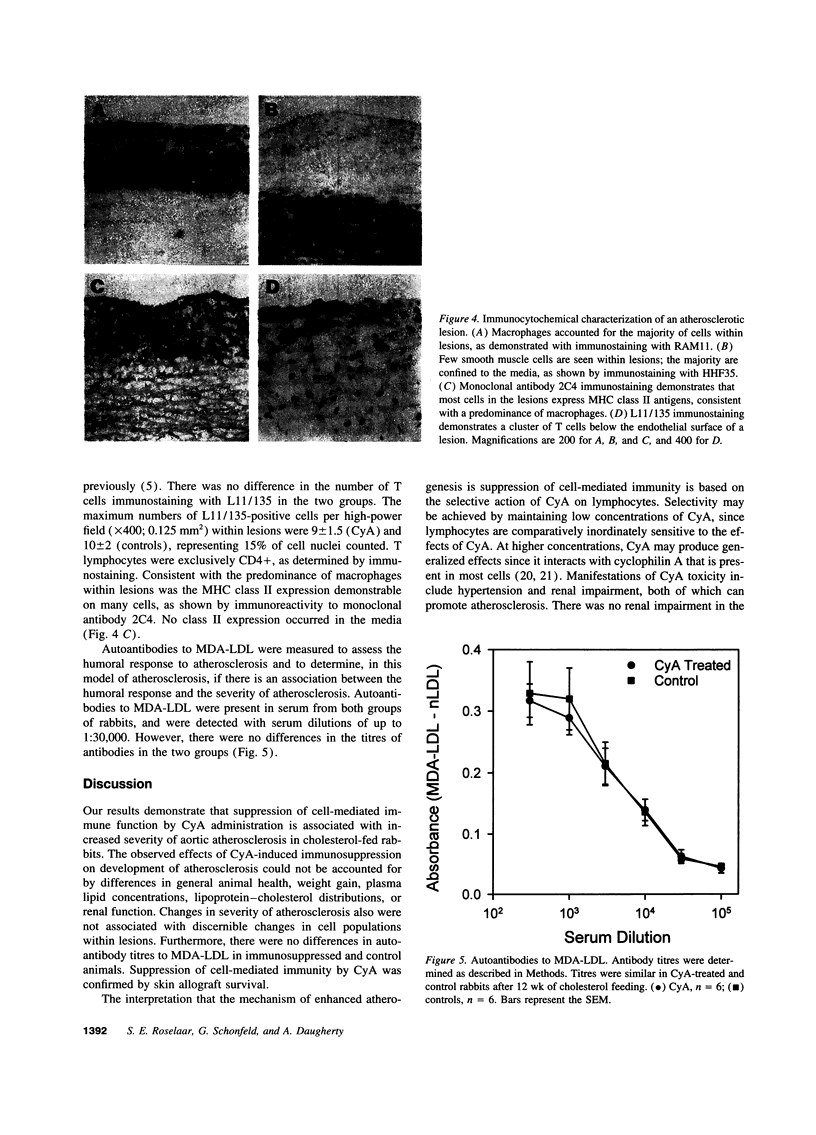

T lymphocytes are present in atherosclerotic lesions, but the role of this cell type in the disease process has not been determined. To determine whether cell-mediated immunity influences atherogenesis, New Zealand White rabbits fed a cholesterol-supplemented diet (0.5% wt/wt) were treated with cyclosporin A (n = 20) or vehicle alone (n = 16) for 12 wk. The dose of cyclosporin A was adjusted so that a blood concentration between 100 and 200 ng/ml was maintained to achieve a selective action T-lymphocytes. Effectiveness of immunosuppression in cyclosporin A-treated rabbits was confirmed by allogeneic skin graft survival. Cyclosporin A administration did not affect total plasma lipid concentrations, body weight, or renal function. Percentage of aortic intimal area covered with atherosclerotic lesions was increased significantly by immunosuppression in both the arch region (75 +/- 3% [mean +/- SEM] compared with 60 +/- 5% in controls; P < 0.01) and the thoracic region (47 +/- 7% vs 27 +/- 6%; P = 0.04). Enhanced atherogenesis was not associated with diminished numbers of T lymphocytes in lesions, changes in T lymphocyte subtype, or any discernible change in cellular composition. Humoral immune responses to oxidized LDL were similar in the two groups: serum titres of autoantibodies against malondialdehyde-modified LDL were equivalent. These data demonstrate that cyclosporin A-induced suppression of cell-mediated immunity increased the development of macrophage-rich atherosclerotic lesions in cholesterol-fed rabbits.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BLIGH E. G., DYER W. J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959 Aug;37(8):911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucy R. P., Xu X. Y., Li J., Huang G. Cyclosporin A-induced autoimmune disease in mice. J Immunol. 1993 Jul 15;151(2):1039–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty A., Roselaar S. E. Lipoprotein oxidation as a mediator of atherogenesis: insights from pharmacological studies. Cardiovasc Res. 1995 Mar;29(3):297–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty A., Zweifel B. S., Schonfeld G. The effects of probucol on the progression of atherosclerosis in mature Watanabe heritable hyperlipidaemic rabbits. Br J Pharmacol. 1991 May;103(1):1013–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Padova F. E. Pharmacology of cyclosporine (sandimmune). V. Pharmacological effects on immune function: in vitro studies. Pharmacol Rev. 1990 Sep;41(3):373–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J. F., Lin Y., Mizel S. B., Bleackley R. C., Harnish D. G., Paetkau V. Induction of interleukin 2 messenger RNA inhibited by cyclosporin A. Science. 1984 Dec 21;226(4681):1439–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.6334364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emeson E. E., Robertson A. L., Jr T lymphocytes in aortic and coronary intimas. Their potential role in atherogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1988 Feb;130(2):369–376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emeson E. E., Shen M. L. Accelerated atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic C57BL/6 mice treated with cyclosporin A. Am J Pathol. 1993 Jun;142(6):1906–1915. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferns G., Reidy M., Ross R. Vascular effects of cyclosporine A in vivo and in vitro. Am J Pathol. 1990 Aug;137(2):403–413. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogelman A. M., Seager J., Haberland M. E., Hokom M., Tanaka R., Edwards P. A. Lymphocyte-conditioned medium protects human monocyte-macrophages from cholesteryl ester accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Feb;79(3):922–926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.3.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyfe A. I., Qiao J. H., Lusis A. J. Immune-deficient mice develop typical atherosclerotic fatty streaks when fed an atherogenic diet. J Clin Invest. 1994 Dec;94(6):2516–2520. doi: 10.1172/JCI117622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garr M. D., Paller M. S. Cyclosporine augments renal but not systemic vascular reactivity. Am J Physiol. 1990 Jan;258(1 Pt 2):F211–F217. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.1.F211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y. J., Hansson G. K. Interferon-gamma inhibits scavenger receptor expression and foam cell formation in human monocyte-derived macrophages. J Clin Invest. 1992 Apr;89(4):1322–1330. doi: 10.1172/JCI115718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granelli-Piperno A., Inaba K., Steinman R. M. Stimulation of lymphokine release from T lymphoblasts. Requirement for mRNA synthesis and inhibition by cyclosporin A. J Exp Med. 1984 Dec 1;160(6):1792–1802. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.6.1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberland M. E., Fogelman A. M., Edwards P. A. Specificity of receptor-mediated recognition of malondialdehyde-modified low density lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Mar;79(6):1712–1716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handschumacher R. E., Harding M. W., Rice J., Drugge R. J., Speicher D. W. Cyclophilin: a specific cytosolic binding protein for cyclosporin A. Science. 1984 Nov 2;226(4674):544–547. doi: 10.1126/science.6238408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson G. K., Holm J., Holm S., Fotev Z., Hedrich H. J., Fingerle J. T lymphocytes inhibit the vascular response to injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Dec 1;88(23):10530–10534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson G. K., Holm J. Interferon-gamma inhibits arterial stenosis after injury. Circulation. 1991 Sep;84(3):1266–1272. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.3.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson G. K., Holm J., Jonasson L. Detection of activated T lymphocytes in the human atherosclerotic plaque. Am J Pathol. 1989 Jul;135(1):169–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson G. K., Jonasson L., Lojsthed B., Stemme S., Kocher O., Gabbiani G. Localization of T lymphocytes and macrophages in fibrous and complicated human atherosclerotic plaques. Atherosclerosis. 1988 Aug;72(2-3):135–141. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(88)90074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson G. K., Seifert P. S., Olsson G., Bondjers G. Immunohistochemical detection of macrophages and T lymphocytes in atherosclerotic lesions of cholesterol-fed rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb. 1991 May-Jun;11(3):745–750. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.3.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T. T., MacGee J., Morrison J. A., Glueck C. J. Quantitative analysis of cholesterol in 5 to 20 microliter of plasma. J Lipid Res. 1974 May;15(3):286–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonasson L., Holm J., Hansson G. K. Cyclosporin A inhibits smooth muscle proliferation in the vascular response to injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Apr;85(7):2303–2306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonasson L., Holm J., Skalli O., Bondjers G., Hansson G. K. Regional accumulations of T cells, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells in the human atherosclerotic plaque. Arteriosclerosis. 1986 Mar-Apr;6(2):131–138. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.6.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuda S., Boyd H. C., Fligner C., Ross R., Gown A. M. Human atherosclerosis. III. Immunocytochemical analysis of the cell composition of lesions of young adults. Am J Pathol. 1992 Apr;140(4):907–914. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koletsky A. J., Harding M. W., Handschumacher R. E. Cyclophilin: distribution and variant properties in normal and neoplastic tissues. J Immunol. 1986 Aug 1;137(3):1054–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo P. T., Wilson A. C., Goldstein R. C., Schaub R. G. Suppression of experimental atherosclerosis in rabbits by interferon-inducing agents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1984 Jan;3(1):129–134. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(84)80438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray H. F., Parthasarathy S., Steinberg D. Oxidatively modified low density lipoprotein is a chemoattractant for human T lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 1993 Aug;92(2):1004–1008. doi: 10.1172/JCI116605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro J. M., van der Walt J. D., Munro C. S., Chalmers J. A., Cox E. L. An immunohistochemical analysis of human aortic fatty streaks. Hum Pathol. 1987 Apr;18(4):375–380. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(87)80168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinski W., Miller E., Witztum J. L. Immunization of low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-deficient rabbits with homologous malondialdehyde-modified LDL reduces atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Jan 31;92(3):821–825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinski W., Ord V. A., Plump A. S., Breslow J. L., Steinberg D., Witztum J. L. ApoE-deficient mice are a model of lipoprotein oxidation in atherogenesis. Demonstration of oxidation-specific epitopes in lesions and high titers of autoantibodies to malondialdehyde-lysine in serum. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994 Apr;14(4):605–616. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinski W., Rosenfeld M. E., Ylä-Herttuala S., Gurtner G. C., Socher S. S., Butler S. W., Parthasarathy S., Carew T. E., Steinberg D., Witztum J. L. Low density lipoprotein undergoes oxidative modification in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Feb;86(4):1372–1376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao J. H., Xie P. Z., Fishbein M. C., Kreuzer J., Drake T. A., Demer L. L., Lusis A. J. Pathology of atheromatous lesions in inbred and genetically engineered mice. Genetic determination of arterial calcification. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994 Sep;14(9):1480–1497. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.9.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayat G., Yatscoff R., Silverman R., McKenna R. A comparison of the immunosuppressive effects of cyclosporine A and cyclosporine G in vivo and in vitro. Transplantation. 1993 Mar;55(3):623–626. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199303000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roullet J. B., Xue H., McCarron D. A., Holcomb S., Bennett W. M. Vascular mechanisms of cyclosporin-induced hypertension in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1994 May;93(5):2244–2250. doi: 10.1172/JCI117222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S., Sakaguchi N. Organ-specific autoimmune disease induced in mice by elimination of T cell subsets. V. Neonatal administration of cyclosporin A causes autoimmune disease. J Immunol. 1989 Jan 15;142(2):471–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen J. T., Ylä-Herttuala S., Yamamoto R., Butler S., Korpela H., Salonen R., Nyyssönen K., Palinski W., Witztum J. L. Autoantibody against oxidised LDL and progression of carotid atherosclerosis. Lancet. 1992 Apr 11;339(8798):883–887. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90926-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A. K., Brundage R. C., Gratwohl A., Sawchuk R. J. Pharmacokinetic model for subcutaneous absorption of cyclosporine in the rabbit during chronic treatment. J Pharm Sci. 1992 Jun;81(6):491–495. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600810602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemme S., Hansson G. K. Immune mechanisms in atherosclerosis. Coron Artery Dis. 1994 Mar;5(3):216–222. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199403000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemme S., Holm J., Hansson G. K. T lymphocytes in human atherosclerotic plaques are memory cells expressing CD45RO and the integrin VLA-1. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992 Feb;12(2):206–211. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemme S., Rymo L., Hansson G. K. Polyclonal origin of T lymphocytes in human atherosclerotic plaques. Lab Invest. 1991 Dec;65(6):654–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Textor S. C., Smith-Powell L., Telles T. Altered pressor responses to NE and ANG II during cyclosporin A administration to conscious rats. Am J Physiol. 1990 Mar;258(3 Pt 2):H854–H860. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.3.H854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick G., Müller P. U., Schwarz S. Effect of cyclosporin A on spontaneous autoimmune thyroiditis of Obese strain (OS) chickens. Eur J Immunol. 1982 Oct;12(10):877–881. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830121014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A. C., Schaub R. G., Goldstein R. C., Kuo P. T. Suppression of aortic atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rabbits by purified rabbit interferon. Arteriosclerosis. 1990 Mar-Apr;10(2):208–214. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.10.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q. B., Oberhuber G., Gruschwitz M., Wick G. Immunology of atherosclerosis: cellular composition and major histocompatibility complex class II antigen expression in aortic intima, fatty streaks, and atherosclerotic plaques in young and aged human specimens. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990 Sep;56(3):344–359. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(90)90155-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylä-Herttuala S., Palinski W., Butler S. W., Picard S., Steinberg D., Witztum J. L. Rabbit and human atherosclerotic lesions contain IgG that recognizes epitopes of oxidized LDL. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994 Jan;14(1):32–40. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]